Abstract

Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis primarily produces a multifocal distribution of pulmonary granulomas in which the pathogen resides. Accordingly, quantitative assessment of the bacterial load and pathology is a substantial challenge in tuberculosis. Such assessments are critical for studies of the pathogenesis and for the development of vaccines and drugs in animal models of experimental M. tuberculosis infection. Stereology enables unbiased quantitation of three-dimensional objects from two-dimensional sections and thus is suited to quantify histological lesions. We have developed a protocol for stereological analysis of the lung in rhesus macaques inoculated with a pathogenic clinical strain of M. tuberculosis (Erdman strain). These animals exhibit a pattern of infection and tuberculosis similar to that of naturally infected humans. Conditions were optimized for collecting lung samples in a nonbiased, random manner. Bacterial load in these samples was assessed by a standard plating assay, and granulomas were graded and enumerated microscopically. Stereological analysis provided quantitative data that supported a significant correlation between bacterial load and lung granulomas. Thus this stereological approach enables a quantitative, statistically valid analysis of the impact of M. tuberculosis infection in the lung and will serve as an essential tool for objectively comparing the efficacy of drugs and vaccines.

Keywords: granuloma, morphometry, quantitative pathology

infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a worldwide disease problem causing ∼20 million new infections and 1.7 million deaths annually (10). Roughly one-third of the global population is infected, and this extensive burden is related to the facile transmission of M. tuberculosis by the aerosol route (i.e., coughing and sneezing). A complication is that M. tuberculosis establishes a latent infection, which can be difficult to diagnose, particularly in developing countries where medical resources are limited (1, 7). The current live-attenuated vaccine, Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), shows a low degree of efficacy at preventing both infection and progression to tuberculosis, and newer vaccine approaches have yet to be fully evaluated in clinical trials (4). Anti-M. tuberculosis drug regimens, generally based on a combination of four antibiotics including isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, require an extended treatment period for cure and are associated with toxicity in some individuals (1). Accordingly, there is a pressing need to significantly improve on vaccines and drugs effective against M. tuberculosis infection and disease.

A major challenge in assessing vaccines and drugs in animal models is the inability to quantify the impact of such interventions on bacterial load and lesion development. Methods that independently quantify the pathology and bacterial load would enable reproducible assessments of interventional therapies and further our understanding of the disease pathogenesis. In this study, we use unbiased stereological methods to independently quantify granulomatous, secondary (nongranulomatous) lesions, and bacterial load for each lung lobe in a nonhuman primate model of M. tuberculosis. As in humans, M. tuberculosis replicates primarily in macrophages within granulomas in the macaque lung and, in some cases, may disseminate to other tissues and organs (2, 6, 8, 9). A proportion of experimentally inoculated macaques show active infection and a proportion harbor M. tuberculosis in a latent state that can be reactivated (2). Thus the nonhuman primate is the model of choice for M. tuberculosis research.

Stereology enables the quantitative assessment of three-dimensional objects through unbiased sampling and measurements made on two-dimensional sections provided that the object is sampled appropriately. This method offers an objective approach to quantify pathological lesions that is independent of observer bias and can be correlated with additional data, such as bacterial load, collected at the same time point. To provide a practical unbiased approach for tissue sampling in a biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) environment, we modified the traditional smooth fractionator approach but retained its accurate and robust sampling scheme (3). We used an efficient study design in which the number of samples, sections, images, and measurements at each analytical stage were kept low without compromising accuracy and still achieved reasonable global precision in the results. Primary objectives of this study were to 1) develop reproducible procedures to collect unbiased representative samples of lung tissue for histology and microbiological culture, 2) apply stereological techniques to quantify the histological changes, and 3) correlate M. tuberculosis loads with histopathological lesions. Since quantification of the histology and bacterial loads are independent measurements from the same lobes, these methods permit insight into the relationship between bacterial numbers and the inflammatory response. These techniques will facilitate quantitative measurements to investigate the disease pathogenesis and test the efficacy of treatments and vaccines in this model of M. tuberculosis infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Screening and selection of rhesus macaques.

Rhesus macaques were from the type D retrovirus-free and SIV-free colony at the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC) at University of California (UC) Davis and were handled in accordance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care Standards. This study was covered by a UC Davis-approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol, and all protocols adhered to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” as prepared by the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Veterinarians, animal health technicians, and staff technicians at CNPRC conducted clinical assessments of animals. This included monitoring weight, temperature, behavior, diarrhea, and opportunistic infections. Six male rhesus macaques, 4 to 5 yr old and in the 6- to 10-kg weight range, were selected from the CNPRC population and evaluated to ensure they met the study inclusion requirements for health status. Indian origin (MMU 35414, MMU 35710, MMU 36365, MMU 36727) and Indian-Chinese hybrids MMU 35446 (1/8 Chinese) and MMU 35603 (1/4 Chinese) were selected. These animals were paired and housed in the animal biosafety level 3 (ABSL-3) facility at the CNPRC. Pre- and postinoculation procedures included physical examinations (weight, temperature), appetite scores, thoracic imaging by X-ray and computerized tomography, blood collections for cryopreservation of plasma and lymphoid cells, clinical chemistry panel, complete blood counts with erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and whole blood assay for M. tuberculosis immune cell-mediated responses.

Biosafety facilities.

Studies of M. tuberculosis in macaques were conducted in an ABSL-3 facility at the CNPRC that contains animal rooms and a separate necropsy/procedure room with a downdraft necropsy table, ducted biosafety cabinet, and other equipment needed for this study. Laboratory activities (lung homogenization and bacterial culture) were performed at the BSL-3 facility at the Center for Comparative Medicine, immediately adjacent to the CNPRC. The UC Davis Environmental Health and Safety Office approved of the ABSL-3 and BSL-3 facilities and activities for research on M. tuberculosis infection in the nonhuman primate. The ABSL-3 and BSL-3 facilities adhered to guidelines outlined in the Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories Manual.

Titration of M. tuberculosis stock.

A stock of the M. tuberculosis clinical strain (Erdman strain, lot K01), at 2.4 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml, was obtained from the Food and Drug Administration (Bethesda, MD) and stored at −80°C. One ml of PBS with 0.05% Tween 80 was added to 1 ml of this stock, mixed by vortexing, serially diluted 10-fold in Middlebrook broth medium, and plated on Middlebrook 7H11-ADC agar dishes (BD Diagnostics) to measure CFU. The titer at the time of inoculation in this study was ∼1.7 × 108 CFU/ml.

Bronchoscopic inoculation.

A fiberoptic bronchoscope (single channel; 2.8 mm outer diameter) BF-XP60 (Olympus) was used for inoculating 500 CFU of M. tuberculosis in 3 ml of sterile saline. The bronchoscope was disinfected with Cidex before and after each procedure. Macaques were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of the appropriate anesthetic agent and dose (ketamine 10 mg/kg and medetomidine 15–30 μg/kg). For medetomidine reversal, atipamezole was administered at equal volume to medetomidine with a dose range of 0.075–0.15 mg/kg. The animal was placed in dorsal recumbency on the procedure table, and its arms were restrained slightly above its head. The mouth was maintained in a partially open position. A syringe filled with 3–5 ml of 1% lidocaine was attached to the biopsy port of the scope and bronchoscopic inoculation was visualized by utilizing the eyepiece included with the basic bronchoscopy equipment and with a camera and monitor. Using a nonsterile gauze pad, the animal's tongue was pulled out of its mouth and over its bottom incisors. A laryngoscope was gently placed at the base of the epiglottis and pressure was applied until the laryngeal folds came into view and the folds were sprayed with a small amount of Cetacaine. The end of the scope was passed between the folds into the trachea without twisting the filaments. If the animal coughed, small amounts of lidocaine were administered through the biopsy port until coughing subsided. A bite guard was positioned just caudal to the canine teeth so the animal could not sever the flexible portion of the scope. The bronchoscope was maneuvered into the right mainstem bronchus and advanced until it was wedged in a subsegmental bronchus. The condition of the bronchial tissue at the wedge point (e.g., bloody, inflamed, thickened, etc.) was noted. Respiratory rate, breathing pattern (e.g., shallow vs. deep), and oral mucous membrane color were monitored. The M. tuberculosis suspension was vortexed, and a volume of 3 ml was drawn into a 5-ml syringe. The lidocaine syringe was detached from the biopsy port, and the syringe containing the inoculum was attached. Bacterial suspension was injected and the syringe was removed from the biopsy port and safely discarded. A 5-ml syringe containing 3 ml saline was attached to the biopsy port and the contents were injected. This syringe was removed and replaced with a 5-ml syringe containing only air, which was injected to flush the contents of the biopsy channel into the lung. The bronchoscope and bite guard were removed from the animal, who was then placed on its left side. Respiratory rate, breathing pattern, and mucous membrane color were closely monitored, and gentle coupage was performed on the right thorax if necessary. Oxygen was administered if needed via a nose cone until the respiration and/or coloration improved. The animal was returned to its cage, placed in left lateral recumbency, and monitored until it fully recovered from anesthesia and was able to remain upright.

Experimental end point.

The fixed live-phase end point was 24 wk postinfection. Two of the group of six macaques (MMU 36365 and MMU 36727) became moribund at 15 wk and were humanely euthanized by a barbiturate overdose and subjected to the necropsy procedures described below. The remaining four macaques that survived for 24 wk postinfection were scheduled for euthanasia and necropsy as close together as practical.

Necropsy and pathology.

Necropsy and pathology procedures on the M. tuberculosis-infected macaques were performed by veterinary pathologists and support staff in the necropsy room in the ABSL-3 facility. In the ABSL3 animal holding room, the macaque was sedated with intramuscular ketamine. The animal was transported to the ABSL3 necropsy room and shaved on the ventral surface, and the skin was cleaned with Betadine scrub followed by ethanol to minimize microbial contamination. An overdose of pentobarbital sodium (Fatal-Plus, Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI) was administered to each animal, and a ventral midline incision was extended from the chin to the pubis. The trachea was exposed and clamped, the abdominal cavity was opened, and access to the thoracic contents was accomplished by removal of the anterior portion of the rib cage. Gross examination of the cavities and exposed organs was performed and findings were recorded and photographed. After removal of the heart, the trachea was transected proximal to the clamp, and the lungs were removed, photographed, and weighed.

The gross pathology of the lungs was scored by a semiquantitative grading scheme. Points were assigned for each lobe based on granuloma prevalence as follows: no visible granulomas 0 points, 1–3 visible granulomas 1 point, 4–10 visible granulomas 2 points, >10 granulomas 3 points, miliary pattern 4 points. A separate score was given based on the size of the largest granuloma as follows: no granulomas present 0 points, <1–2 mm 1 point, 3–4 mm 2 points, >4 mm 3 points. These scores were summed for a total score.

Hilar lymph nodes were sampled for histopathology, bacterial culture, and cryopreservation. Samples of the spleen and liver were collected for histopathology. Bronchial, mediastinal, and mesenteric lymph nodes, as well as gross lesions in any other organs, were also collected and processed for histopathology.

Morphometric estimate of lung lobe volumes.

For stereological sampling and volume estimation, lung lobes (Fig. 1A) were cut into 5-mm slabs using a Thomas blade and then photographed with a ruler in place to assist in estimation of the total lobe volume by use of a Cavalieri estimator (Fig. 1B) (3). The lung slabs were subsequently sampled for bacterial culture and histopathology as described below. Following necropsy, the digital images of the slab sections were used to estimate lobe volumes. In short, the images were imported into Adobe Photoshop, where a grid was overlaid and points were counted that fell on the tissue. The area per point on the grid was determined from the ruler in the digital image. A final lobe volume was determined by multiplying the total number of points by the area per point and the slab thickness (13).

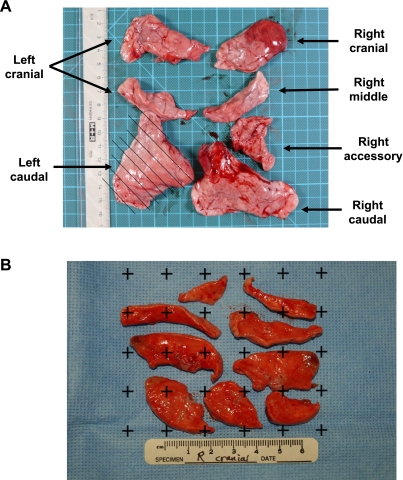

Fig. 1.

Cavalieri estimate of lung lobe volume. A: lung lobes separated for analysis. The hatching on the left caudal lobe indicates the 5-mm slab sectioning that was performed for each lobe. B: slabs were photographed with a ruler in place at the time of necropsy. Subsequently, a grid with a known area per point was placed over the image. Points that fell on the tissue were counted to estimate the lobe volume.

Random selection of lung samples.

The 5-mm slab sections from each individual lung lobe were placed underneath a template containing regularly spaced 5-mm holes (constructed by the Chemistry Department Machine Shop at UC Davis). Overall dimensions are 25 cm × 25 cm × 0.5 cm. The distance from the edge to the first hole is 0.5 cm, and the distance from the center of one hole to the center of an adjacent hole is 1 cm. If every hole is sampled, regardless of tissue size, it will result in sampling 25% of the tissue. For sampling efficiency in a BSL-3 environment, a 5-mm biopsy punch was used to collect tissue samples through the template holes. The lung slabs were laid out and the template was placed without regard to the tissue beneath so as to randomize sample selection (Fig. 2A). Some holes were positioned over areas with no tissue. The biopsy punch was used to collect the tissue sample from each hole that had tissue beneath it by using a stratified sampling method with a random start (Fig. 2B). All holes with tissue in the template were used for sampling. Tissue samples were processed as follows: 1) one sample for preparing a homogenate for plating to determine M. tuberculosis bacterial load (CFU), a 2) second sample for fixation in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for histopathology, and 3) a third sample was cryopreserved for archival storage at −80°C. This method of sampling provides a fraction of ∼10% of the lung for both the M. tuberculosis load and lesion volume estimate.

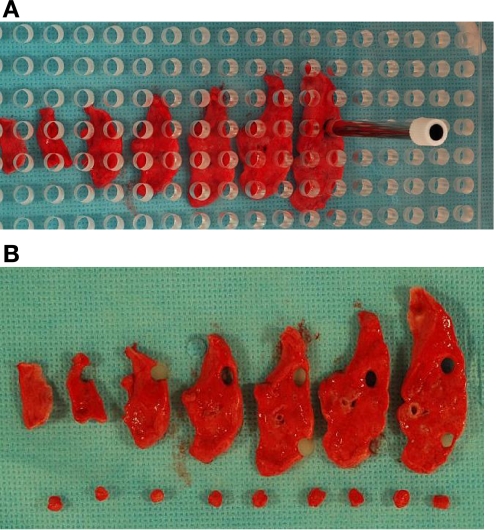

Fig. 2.

Sampling of lung lobe using Plexiglas grid. A: a template containing evenly spaced 5-mm holes was randomly placed over the slab sections of each lung lobe. Using stratified uniform sampling with a random start, we collected samples for both histological and microbiological culture analysis. A biopsy punch instrument was used to collect the samples through the template. B: ∼10% from each lung lobe was collected for both microbiological culture and histology.

Histopathology and scoring of microscopic lung lesions.

The aggregate samples from a single lobe were grouped and processed to create one or more paraffin blocks. A 5-μm section was taken from each block and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Fig. 3A). The slides were scanned with an Olympus VS110 whole slide scanner, and the resulting images were analyzed with Visiopharm (Denmark) software (VIS MicroImager and NewCAST) to calculate the volume of granulomatous and nongranulomatous lesions and the reference volume of lung tissue sampled by point counting for each lobe. Granulomas were defined as a central core of macrophages with or without necrosis and mineralization surrounded by outer rim of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibrosis. Nongranulomatous lesions included other pathological changes including peribronchial/perivascular inflammation, type II cell hyperplasia and necrosis or fibrosis (not associated with granulomas). Seventy-five fields captured with a ×10 objective lens were selected from the punch biopsies of each lobe by stratified sampling with a random start with the VIS MicroImager module (Fig. 3B). Using a double-lattice test grid of 4/16 coarse to fine points, we estimated the volume densities of lesion (granulomatous or nongranulomatous quantified by fine points) and parenchymal tissue (reference volume quantified by coarse points) using point counting (Fig. 4). The volume of lesion (granulomatous or nongranulomatous) was normalized to the volume of lung in the counted fields, which in turn was multiplied by the macroscopic lobe volume as determined by the Cavalieri estimate. This resulted in an absolute volume of lesion (cm3) for each lung lobe. Detailed histopathology, but not quantification, was also performed on the hilar lymph nodes and other organs (data not shown).

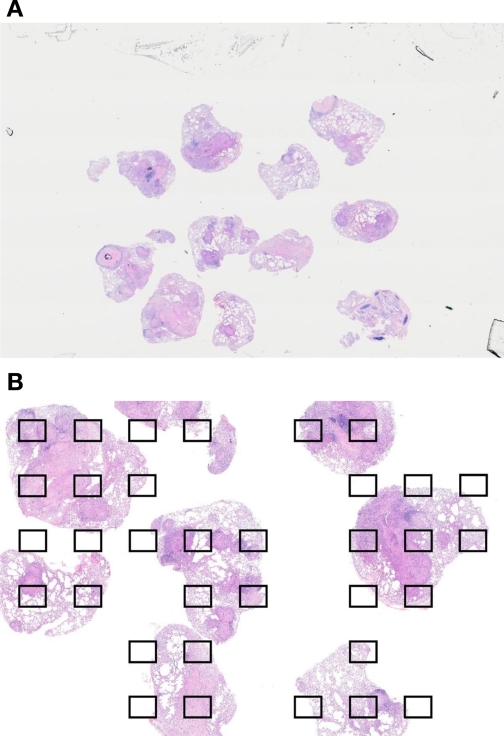

Fig. 3.

Histological sampling of lung lobe samples. A: aggregated samples from one lobe were embedded in 1 or 2 paraffin blocks; 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and digitally scanned by use of an Olympus slide scanner. B: Visiopharm VIS (MicroImager module) software was used to select microscopic fields for quantification by systematic uniform sampling with a random start. Seventy-five fields were selected across all the samples from 1 lobe for quantification.

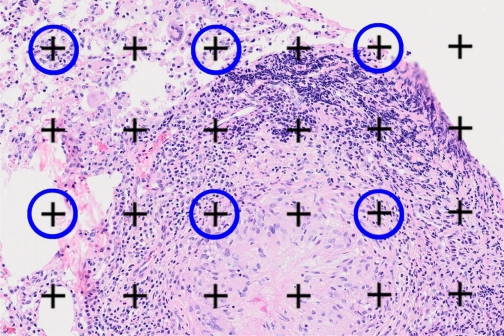

Fig. 4.

Volume estimate of granulomas on histological sections. The number of fine points (black crosses) landing on a granuloma were recorded for each microscopic field. The number of coarse points (encircled in blue) landing on lung tissue were also counted as a reference volume. A similar estimate was performed for points landing on “nongranulomatous” lesions.

Homogenization of lung lobe samples and lymph nodes.

The original plan described a two-step process for homogenization of lung lobes with blade-type homogenizers. Preliminary experiments were performed on lung from uninfected macaques to optimize this method. However, there were significant concerns about biosafety because of extensive aerosolization and workload because of the number of samples and the need to clean the homogenizers for each sample. Accordingly, we investigated a bead-mill-type (BMT) homogenizer, which uses sealed tubes containing ceramic beads and a relatively simple vortex system (Ultra-Turrax; IKA, Staufen, Germany). Preliminary studies were done with the BMT system on uninfected lung lobes and core samples to optimize homogenization conditions. Briefly, using the stratified sampling method with the Plexiglas template, the tissue samples per lobe were pooled and added into the BMT tube containing 2 ml PBS-0.04% Tween 80. Ceramic beads (6-mm diameter) were added into each tube; after securing the cap, we placed the tube onto the holding dock of the Ultra-Turrax vortex system. Samples from individual lung lobes were homogenized at maximum speed, six times at 30-s intervals. The homogenized tissue samples were on ice until plating.

Hilar lymph nodes from each animal were collected as a pool and were not collected by the stratified sampling method. These lymph nodes were pooled and homogenized, similar to lung lobes, for bacterial culture plating.

Bacterial load assessments.

Pooled core samples, derived from the stratified sampling method, were homogenized and filtered through a sterile 70 μM cell strainer (Falcon no. 352350), and the final homogenate volume was measured. Each sample was serially diluted (10-fold) in PBS-0.04% Tween 80. A 100-μl sample from each dilution was plated on 7H11-ADC agar dishes (BD Diagnostics) in duplicates to measure CFU. The agar plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 wk, and bacterial colonies were counted visually for CFU. The number of CFU per lobe volume was calculated as follows: inverse of (homogenate volume used for plating/final homogenate volume posthomogenization) × (average CFU) × (1/0.08333) = CFU/lobe (M. tuberculosis load) where 1/0.08333 is the fraction of lung lobe that was sampled for bacterial culture.

A sample of homogenate from the hilar lymph node pool was similarly plated. Bacterial load was not calculated by volume for this tissue.

Statistical analysis of lung lesions and bacterial load data.

The main goal of the statistical analysis was to estimate the correlation between the culture results (CFU) and the histology (absolute granuloma/nongranuloma volume) for each lung lobe. Since our data set included six monkeys with six lung lobes each, we obtained 36 data points for each variable. Because the data from each lobe within the same lung are not statistically independent, we applied two approaches for the analysis: 1) to estimate the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient for each lobe and 2) to estimate the Pearson coefficient at the lung level from a random-effects model (11), which assumes a latent factor underlying the six lobes for each lung (i.e., monkey) and a random variation between the lobes. In other words, the total variance among the data is decomposed into the between-lung variance and the within-lung variance. Before estimating the Pearson coefficients, logarithmic transformations were applied to each variable to normalize the distribution. The Spearman coefficient was based on ranking of the data. For the lung-level analysis, the Bayesian hierarchical modeling strategy was used to estimate the Pearson coefficient because of the small sample size. This approach assumes that M. tuberculosis CFU and the lesions have a bivariate normal distribution, with random errors representing the variance between lobes within each lung and a two-dimensional vector of random effects representing the variance between animals. The Pearson correlation between the two random effects tests the correlation between M. tuberculosis CFU and lesion. The Bayesian computing was conducted by using WindBUGS 1.4.3 and all other analyses were done by using R 2.11.

RESULTS

Necropsy analysis and description of thoracic lesions.

A scoring system was developed, as described in materials and methods, to assess the prevalence and size of granulomas by lung lobe (Table 1). Positive correlations were found between the gross pathology scores and stereological assessment of granuloma volume at both the animal and lung lobe level. The right caudal lobe received the highest gross pathology score in each animal, reflecting instillation of M. tuberculosis into the right lung. Similar results were found following histological quantification of granuloma volume per lung lobe. MMU 35710 received the lowest gross pathology score corresponding to the lowest volume of granulomas per lung lobe following histological analysis. In contrast, MMU 36727 received the highest gross pathology score correlating with the highest volume of granulomas per lung lobe.

Table 1.

Semiquantitative grading of gross pathology

| Necropsy Score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granuloma prevalence | Granuloma size | Score total | ||

| MMU 35414 | left caudal | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| left cranial | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| right accessory | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| right cranial | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| right caudal | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| right middle | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| MMU 35446 | left caudal | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| left cranial | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| right accessory | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| right cranial | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| right caudal | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| right middle | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| MMU 35603 | left caudal | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| left cranial | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| right accessory | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| right cranial | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| right caudal | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| right middle | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| MMU 35710 | left caudal | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| left cranial | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| right accessory | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| right cranial | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| right caudal | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| right middle | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MMU 36365 | left caudal | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| left cranial | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| right accessory | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| right cranial | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| right caudal | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| right middle | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| MMU 36727 | left caudal | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| left cranial | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| right accessory | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| right cranial | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| right caudal | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| right middle | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

A score was assigned for each lung lobe based on the granuloma prevalence and granuloma size at necropsy. These individual scores were summed for the total score.

Hilar lymph nodes were enlarged in all the rhesus monkeys containing multifocal to coalescing granulomas. Histology confirmed severe necrotizing and granulomatous lymphadenitis effacing much of the normal lymph node architecture. The majority of animals (4/6) had granulomas grossly evident on the diaphragm and/or body wall, demonstrating extension of the pneumonia to a regionally extensive pleuritis associated with pleural adhesions and pleural thickening. Extrapulmonary infection was found in four of the six animals, with the liver and spleen equally affected. The animal with most severe pulmonary disease (MMU 36727) had granulomatous lesions detected in the left kidney, in both eyes, and throughout the brain. Histology confirmed necrotizing pyogranulomatous to granulomatous inflammation in these extrathoracic organs.

Analysis of bacterial load and histological lesions.

Lung samples from each lobe collected with the template were homogenized and tested for M. tuberculosis in the plating assay. A sample of homogenized hilar lymph nodes from each macaque was also tested although the stereological sampling method was not used for collection. The lymph nodes from all six animals were positive for M. tuberculosis with CFU per gram ranging from 6.5 × 102 to 8 × 103 (data not shown).

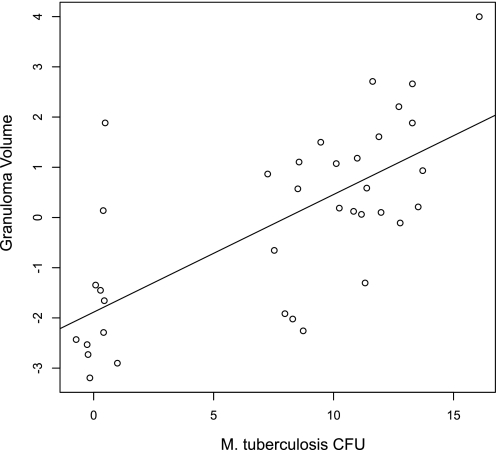

Table 2 summarizes the CFU of M. tuberculosis cultured from each lung lobe and the absolute volume (cm3) of granulomatous, nongranulomatous, and total lesion determined from stereological analysis of the histology. As shown in Fig. 5, there is a notable correlation between the M. tuberculosis load (CFU/lobe) and absolute granuloma volume in the lung. Ignoring the fact that the data within the lung lobes are dependent, we estimated the Pearson coefficient, which is 0.71 between M. tuberculosis fraction loads and granuloma volume.

Table 2.

Analysis of bacterial load and histological lesions

| Mtb Load, CFU | Granuloma, cm3 | Nongranuloma, cm3 | Total Lesion, cm3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMU 35414 | left caudal | 240250 | 2.291 | 4.055 | 6.346 |

| left cranial | 0 | 1.034 | 3.025 | 4.059 | |

| right accessory | 53426 | 1.238 | 1.668 | 2.906 | |

| right cranial | 2016 | 0.669 | 3.805 | 4.474 | |

| right caudal | 102484 | 11.625 | 5.151 | 16.776 | |

| right middle | 0 | 0.022 | 2.047 | 2.070 | |

| MMU 35446 | left caudal | 0 | 0.459 | 4.588 | 5.047 |

| left cranial | 7140 | 1.630 | 3.681 | 5.311 | |

| right accessory | 1680 | 0.170 | 0.804 | 0.973 | |

| right cranial | 3864 | 0.000 | 2.641 | 2.641 | |

| right caudal | 616585 | 8.587 | 7.648 | 16.235 | |

| right middle | 3864 | 1.437 | 2.440 | 3.877 | |

| MMU 35603 | left caudal | 0 | 0.094 | 2.544 | 2.637 |

| left cranial | 166327 | 0.532 | 4.298 | 4.830 | |

| right accessory | 28225 | 3.635 | 3.235 | 6.870 | |

| right cranial | 0 | 6.869 | 12.052 | 18.920 | |

| right caudal | 865235 | 15.673 | 12.401 | 28.073 | |

| right middle | 80475 | 3.156 | 4.538 | 7.694 | |

| MMU 35710 | left caudal | 0 | 0.000 | 3.584 | 3.584 |

| left cranial | 0 | 0.000 | 2.889 | 2.889 | |

| right accessory | 0 | 0.000 | 1.128 | 1.128 | |

| right cranial | 0 | 0.000 | 1.327 | 1.327 | |

| right caudal | 17473 | 1.647 | 4.066 | 5.713 | |

| right middle | 0 | 0.009 | 0.837 | 0.847 | |

| MMU 36365 | left caudal | 47042 | 0.224 | 2.687 | 2.911 |

| left cranial | 0 | 0.000 | 1.928 | 1.928 | |

| right accessory | 4704 | 0.148 | 1.129 | 1.277 | |

| right cranial | 102484 | 1.755 | 2.993 | 4.748 | |

| right caudal | 436817 | 14.885 | 8.095 | 22.980 | |

| right middle | 1848 | 0.041 | 1.887 | 1.928 | |

| MMU 36727 | left caudal | 104164 | 1.749 | 4.802 | 6.551 |

| left cranial | 25285 | 2.756 | 3.906 | 6.662 | |

| right accessory | 169687 | 3.025 | 2.457 | 5.482 | |

| right cranial | 1512060 | 2.998 | 4.205 | 7.204 | |

| right caudal | 12415697 | 34.005 | 6.762 | 40.767 | |

| right middle | 787952 | 1.360 | 3.687 | 5.046 |

The stereological approach, described in materials and methods, was used to determine Mycobacterium tuberculosis load (CFU) and histological changes (volume of granuloma or nongranulomatous lesion) in each lobe. Total lesion refers to the sum of granuloma and nongranulomatous lesion.

Fig. 5.

Scatterplot of M. tuberculosis colony-forming unit (CFU) load and granuloma volume. Logarithmic transformation of all 36 data points was performed. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.71, suggesting a strong correlation between CFU and absolute granuloma volume (cm3). The number of CFU per lobe volume was calculated as follows: inverse of (homogenate volume used for plating/final homogenate volume posthomogenization) × (average CFU) × (1/0.08333) = CFU/lobe (M. tuberculosis load) where 1/0.08333 is the fraction of lung lobe that was sampled for bacterial culture. This approach provides a means to estimate the correlation between the 2 variables of interest.

When fitting the Bayesian hierarchical model, we tried to specify noninformative prior distributions for the parameters involved. For example, the normal prior distributions were set with large variance (i.e., 100,000). As for the prior distribution of the random-effects covariance matrix, an Invert-Wishart distribution was assumed with a large scale matrix and degrees of freedom of 3. In WinBUGS, one single chain was run with 6,000 burn-in iterations, and 154,000 iterations were used for summarizing the posterior distribution of the parameters of interest. The parameter of primary interest is the Pearson correlation coefficient, which was calculated by the Bayesian hierarchical modeling strategy. The estimate of Pearson correlation coefficient was −0.771 with 95% credible interval (0.260, 0.968), which suggests a strong correlation between M. tuberculosis fraction load and granuloma volume. Similarly, we observed posterior distribution of Pearson coefficient between M. tuberculosis fraction load and nongranuloma lesion with point estimate of 0.475 and 95% credible interval (−0.303, 0.905), suggesting that the correlation between the M. tuberculosis fraction load and nongranuloma lesion was not strong.

For each lobe, both the Pearson and Spearman coefficients were estimated and presented in Table 3, where bold font indicates that the coefficients are significantly different from zero. Note that both Pearson and Spearman coefficients follow t-distributions with different formulations. The correlation between the M. tuberculosis fraction load and granuloma volume is stronger than that between the M. tuberculosis fraction load and the nongranuloma volume for most lobes, except for the left cranial lobe and with similar results for the right middle lobe.

Table 3.

Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients between M. tuberculosis fraction loads and absolute granuloma or nongranuloma lesion for each lobe

| Lung lobe | Analysis | Granuloma | Nongranulomatous Lesion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left caudal | Pearson | 0.75 | 0.19 |

| Left caudal | Spearman | 0.82 | 0.39 |

| Left cranial | Pearson | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| Left cranial | Spearman | 0.52 | 0.94 |

| Right accessary | Pearson | 0.84 | 0.57 |

| Right accessary | Spearman | 0.77 | 0.77 |

| Right caudal | Pearson | 0.89 | 0.59 |

| Right caudal | Spearman | 0.83 | 0.60 |

| Right cranial | Pearson | 0.20 | −0.08 |

| Right cranial | Spearman | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| Right middle | Pearson | 0.83 | 0.82 |

| Right middle | Spearman | 0.81 | 0.84 |

Values in bold font indicate that the correlation coefficients are significantly different from zero.

DISCUSSION

To characterize this model of M. tuberculosis, a complete necropsy was performed to assess the extent of lesions. Despite instillation with the same M. tuberculosis dose, disease progression was variable in individuals with two animals becoming severely ill, which necessitated euthanasia prior to completion of the study. One of these animals (MMU 36727) had the most extensive disease at necropsy with extensive involvement of extrathoracic organs.

In contrast to the semiquantitative scoring schemes used to evaluate the gross pathology, this study applied unbiased stereological techniques to accurately quantify and correlate bacterial loads and histological lesions from each lung lobe. Two stereological principles were applied throughout the assessment: 1) stratified random sampling of the tissue at the macroscopic and microscopic level to ensure unbiased sample collection and 2) validated methods to measure structural features (e.g., granulomas) from three-dimensional organs by use of two-dimensional tissue sections. The template facilitated efficient and systematic sampling of each entire lung lobe for histopathology and bacterial culture. Stratified sampling at the microscopic level was easily achieved by using whole slide scanning and the stereology VIS MicroImager module (Visopharm, Denmark) on the digital H and E-stained image. Finally, we quantified the absolute volume of granuloma and nongranulomatous lesions in each lobe.

These methods are feasible for large-scale studies. With assistance, sample collection can be efficient and completed in ∼1 h per animal. The use of the template permits unbiased stratified sampling of tissue to use in other assays such as microbiological culture at the same time point. Correlations are then easily made between the morphological alterations and these other metrics in the lung lobe as demonstrated in this study with bacterial load. Although not done in this study, punch biopsies from other studies have been immediately stored in RNA later for subsequent RNA analysis by the same sampling technique (K. L. Oslund and D. M. Hyde, unpublished observations).

We found an overall significant positive correlation between the volume of granulomatous lesions and the M. tuberculosis load with significance in all lung lobes except the cranial lobes. These results are not surprising because M. tuberculosis primarily resides in macrophages, which are the predominant cell type in granulomas (14, 16). Most of the granulomas in these animals were well developed surrounded by lymphocytes and a rim of fibrosis, the type of tuberculoid granuloma that has been associated with an efficient host response to localizing the bacteria (20, 21). The lack of a correlation in the cranial lobes is interesting and implies discordance between the immune response and the presence of the organism in these lobes. It would be interesting to assess the correlation between bacterial load and histological lesions at other time points in this model to provide further insight into the pathogenesis.

In contrast, only the left cranial and right middle lobes demonstrated a positive correlation between M. tuberculosis load and nongranulomatous lesion volume. The nongranulomatous category was a constellation of different lesions (inflammation, necrosis, and fibrosis not associated with granulomas), which are likely not directly attributable to the presence of M. tuberculosis but more likely secondary to the presence of the granulomas, an overzealous immune response and/or reparative attempts by the host. The nongranulomatous lesions quantified in this study have, in part, been described as secondary lesions and are thought to result from hematogenous dissemination of the bacteria 3–4 wk following initial inoculation in the guinea pig model (5, 12, 19). Our results could be consistent with this, although the lack of a correlation in this study implies that there was not persistence of the bacteria within these lesions. Although the pathogenesis of these secondary lesions has received little attention in nonhuman primate models, they likely contribute to the morbidity of patients, and interventional therapy may prevent or ameliorate these lesions. Thus quantification of lesions other than granulomas can give insight into the pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis and serve as an additional metric to assess host response to treatments and vaccines.

Although stereology is an established method to estimate structural differences and differences in cell numbers in pathological tissues (3, 22), this is the first time design-based stereology has been used to quantify granulomatous lesions from histology sections as a host response to M. tuberculosis infection. Stereology has been used previously to estimate lesion volume in conjunction with an imaging modality such as MRI (15). Using a different model of M. tuberculosis in macaques, Sharpe and colleagues (17) quantified pulmonary lesions from MRI digital stacks of formalin-fixed lungs ex vivo based on the Cavalieri principle. They found estimation of the total lesion volume relative to the fixed lung volume was the best indication of disease burden compared with radiographs, semiquantitative pathology scores, and clinical data (6, 9, 18). Our findings support these studies and extend them to assess the microscopic changes, a specific and sensitive assessment of the host response to M. tuberculosis infection. The method of sampling used in this study for M. tuberculosis assessment provided excellent correlation with quantitative pathology. This sampling approach can be applied for multiple end points to assess vaccine or drug efficacy in M. tuberculosis infection. These methods will provide accurate measurements that are sensitive enough to distinguish subtle effects of treatments even with small animal numbers.

In summary, we have developed efficient and reproducible techniques to measure and correlate microbiological and pathological data from lungs following M. tuberculosis infection. This model will serve as a basis for quantitative evaluation of treatment and vaccine interventions to mitigate the ongoing public health burden of M. tuberculosis.

GRANTS

This research was supported by grants from the Aeras Foundation for Global Health and from the National Institutes of Health (NCRR Base Grant RR00169 and NCRR ARRA Supplement P51 RR000169).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals for helpful discussions: Frank Verreck, Randall Basaraba, Charles Scanga, Yasir Skieky, Donata Sizemore, and Edwin Kleine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Barry CE, Boshoff BI, 3rd, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 7: 845–855, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Capuano SV, 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S, Zinovik A, Myers A, Lin PL, Bissel S, Fuhrman C, Klein E, Flynn JL. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun 71: 5831–5844, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsia CC, Hyde DM, Ochs M, Weibel ER. An official research policy statement of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society: standards for quantitative assessment of lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 394–418, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaufmann SH, Hussey G, Lambert PH. New vaccines for tuberculosis. Lancet 375: 2110–2119, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lenaerts AJ, Hoff D, Aly S, Ehlers S, Andries K, Cantarero L, Orme IM, Basaraba RJ. Location of persisting mycobacteria in a guinea pig model of tuberculosis revealed by r207910. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51: 3338–3345, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewinsohn DM, Tydeman IS, Frieder M, Grotzke JE, Lines RA, Ahmed S, Prongay KD, Primack SL, Colgin LM, Lewis AD, Lewinsohn DA. High resolution radiographic and fine immunological definition of TB disease progression in the rhesus macaque. Microbes Infect 8: 2587–2598, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lin PL, Flynn JL. Understanding latent tuberculosis: a moving target. J Immunol 185: 15–22, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin PL, Pawar S, Myers A, Pegu A, Fuhrman C, Reinhart TA, Capuano SV, Klein E, Flynn JL. Early events in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in cynomolgus macaques. Infect Immun 74: 3790–3803, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lin PL, Rodgers M, Smith L, Bigbee M, Myers A, Bigbee C, Chiosea I, Capuano SV, Fuhrman C, Klein E, Flynn JL. Quantitative comparison of active and latent tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque model. Infect Immun 77: 4631–4642, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lonnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, Chauhan LS, Floyd K, Glaziou P, Raviglione MC. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010–50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet 375: 1814–1829, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCulloch CE. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. New York: Wiley, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12. McMurray DN. Hematogenous reseeding of the lung in low-dose, aerosol-infected guinea pigs: unique features of the host-pathogen interface in secondary tubercles. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 83: 131–134, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michel RP, Cruz-Orive LM. Application of the Cavalieri principle and vertical sections method to lung: estimation of volume and pleural surface area. J Microsc 150: 117–136, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pieters J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the macrophage: maintaining a balance. Cell Host Microbe 3: 399–407, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roberts NM, Puddephat J, McNulty V. The benefit of stereology for quantitative radiology. Br J Radiol 73: 679–697, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saunders BM, Britton WJ. Life and death in the granuloma: immunopathology of tuberculosis. Immunol Cell Biol 85: 103–111, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharpe SA, Eschelbach E, Basaraba RJ, Gleeson F, Hall GA, McIntyre A, Williams A, Kraft SL, Clark S, Gooch K, Hatch G, Orme IM, Marsh PD, Dennis MJ. Determination of lesion volume by MRI and stereology in a macaque model of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89: 405–416, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sharpe SA, McShane H, Dennis MJ, Basaraba RJ, Gleeson F, Hall G, McIntyre A, Gooch K, Clark S, Beveridge NE, Nuth E, White A, Marriott A, Dowall S, Hill AV, Williams A, Marsh PD. Establishment of an aerosol challenge model of tuberculosis in rhesus macaques and an evaluation of endpoints for vaccine testing. Clin Vaccine Immunol 17: 1170–1182, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith DW, Balasubramanian V, Wiegeshaus E. A guinea pig model of experimental airborne tuberculosis for evaluation of the response to chemotherapy: the effect on bacilli in the initial phase of treatment. Tubercle 72: 223–231, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi GA, Trusov V, Jorg S, Pradl S, Titukhina M, Mishenko V, Gushina N, Kaufmann SH. Human tuberculous granulomas induce peripheral lymphoid follicle-like structures to orchestrate local host defence in the lung. J Pathol 204: 217–228, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ulrichs T, Kaufmann SH. New insights into the function of granulomas in human tuberculosis. J Pathol 208: 261–269, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weibel ER, Hsia CC, Ochs M. How much is there really? Why stereology is essential in lung morphometry. J Appl Physiol 102: 459–467, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]