Abstract

At the cellular level, 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) serves as a critical link between energy homeostasis and the regulation of fundamental biological activities, including apoptosis. Angiotensin (Ang) II plays a key role in fibrotic lung remodeling. We recently demonstrated that Ang II induces apoptosis in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) through the Ang type 2 receptor (AT2). AT2 activates Src-homology two-domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) in a signaling cascade leading to Bcl-xL mRNA destabilization and initiation of intrinsic apoptosis. We investigated the requirement of AMPK and ATP generation for Ang II-induced apoptosis in PAEC. Ang II activated AMPK, which was required for ATP generation. Inhibition of ATP production by compound C, an AMPK inhibitor, or by oligomycin suppressed Ang II-induced apoptosis. Experiments in Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells expressing ectopic AT2 (wild-type, mutant D90A, or carboxy terminal truncated mutant tC319) demonstrated that AT2 activation of AMPK required the active conformation of the receptor and the carboxy terminal 44 amino acids. AMPK associated with and activated SHP-2 and was required for Bcl-xL mRNA destabilization. These are the first findings demonstrating that AMPK is activated by Ang II to produce ATP required for apoptosis. Our data also indicate that AMPK plays an energy-independent role by mediating SHP-2 activation.

Keywords: AMP-dependent kinase, Src-homology two-domain-containing phosphatase-2, Bcl-xL, endothelial cells, G protein-coupled receptor

cellular activities such as growth, differentiation, apoptosis, polarity, and migration must be coordinated with the availability of metabolic energy. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is the chief sensor of the fuel metabolism and cellular energy, switching on pathways that conserve or produce ATP (including glucose uptake, glycolysis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and fatty acid oxidation) and switching off ATP-consuming processes (such as synthesis of proteins, fatty acids, glycogen, or cholesterol) (9, 36). AMPK is a heterotrimeric enzyme consisting of an α-catalytic subunit with serine/threonine kinase activity, as well as β- and γ-regulatory subunits (9, 10, 38, 42). AMPK activity is typically regulated by decreased ATP levels, associated with an increased AMP:ATP ratio within cells. Under these conditions, the binding of AMP to the γ-subunit activates AMPK through a complex mechanism believed to involve an allosteric effect on the kinase that allows increased phosphorylation of the α-subunit at Thr172 (9, 32, 38). Several kinases have been identified to phosphorylate the α-subunit, including the tumor suppressor serine/threonine kinase LKB1, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases (CAMKKs), and the mammalian transforming growth factor β-activated kinase (13, 41). It has also been suggested that increased phosphorylation of AMPK-α can occur through the inhibition of protein phosphatases, especially those that dephosphorylate Thr172 (31).

A number of reports provide evidence for AMPK activation in cell survival (13), but AMPK activation has also been shown to be required for apoptotic signaling. A variety of drugs, including doxorubicin, vincristin, tributyltin, curcumin, quercetin, and capsaicin, were demonstrated to induce cellular apoptosis in an AMPK-dependent manner (2, 3, 15, 21, 22, 28). Intracellularly transported adenosine-induced apoptosis was also found to require AMPK activation in some cancer cells (45). Thus it appears that AMPK signaling for survival or apoptosis depends upon the context of the signaling

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) regulate a wide variety of biological activities in cells and have been demonstrated to modulate AMPK activity (13). A number of mechanisms have been identified for GPCR activation or inhibition of AMPK that differ according to the subtype of α-subunit coupled to the GPCR and the cell type (13). The Gs-coupled β2-adrenergic receptor was demonstrated to activate AMPK by increasing the AMP:ATP ratio (23). Several other Gs-coupled receptors (including the β1-adrenergic receptor) were demonstrated to activate AMPK in a mechanism believed to involve adenylate cyclase and protein kinase A-dependent activation of LKB1 (13). Gq-coupled GPCRs [including the α1-adrenergic, bradykinin, histamine H1, proteinase-activated receptor 1 (a thrombin receptor), ghrelin, and purinergic receptors] were demonstrated to activate AMPK through the increase of intracellular calcium concentrations and activation of CAMKK (13, 16). In contrast, several of the Gi-coupled members of the GPCR family were shown to inhibit AMPK activation, potentially through the inhibition of adenylate cyclase (13).

Signaling via the vasoactive peptide angiotensin II (Ang II) GPCRs has been studied primarily with regard to blood pressure homeostasis, but more recently these studies have been extended to include the regulation of cell growth and survival. Ang II exerts its biological effects primarily via two types of GPCRs, the Ang type 1 receptor (AT1) and the type 2 receptor (AT2) (4). The Gq-coupled AT1 receptor is associated with cell growth in some cell types (4, 11, 30). In contrast, the AT2 receptor has been shown to induce growth arrest and apoptosis (4, 20). Apoptotic signaling through AT2 has been associated with proapoptotic activities during fibrotic lung remodeling (37, 39, 40). AT2 may couple through Gi or Gs depending on the cell type but also has significant G protein-independent signaling through the activation of phosphatases or the NO/cGMP system (7, 34). The AT2 receptor utilizes the Gαs protein subunit as an adaptor for the activation of the Src-homology two-domain-containing phosphatases (SHPs), in a mechanism that involves coupling of Gαs with AT2 but not activation of Gαs (7, 20). Although AT1 was demonstrated to activate AMPK in vascular smooth muscle cells through the generation of NADPH oxidase O2− and H2O2 (27), AT2 has not been previously demonstrated to either activate or inhibit AMPK.

As stated above, Ang II signaling through the AT2 receptor has been demonstrated to play a key role in apoptosis in lung fibrosis (37, 39, 40). Our laboratory recently showed that Ang II induces apoptosis in primary lung pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) through the AT2 receptor via the mitochondria-dependent (intrinsic) pathway (20). Ang II treatment caused a reduction of the Bcl-xL mRNA half-life attributable to decreased binding of nucleolin to the Bcl-xL mRNA. Under basal conditions, the binding of nucleolin prevents mRNA degradation signaled by the second AU-rich element (ARE) of the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNA. The decrease in nucleolin binding required SHP-2 activation by AT2. We also determined that AT2 signaling for apoptosis was independent of Gαs activation but instead utilized Gαs in an adaptor-like function (20). In the present study, we investigated the role of AMPK in AT2-induced apoptosis in PAEC. We now provide evidence that Ang II-induced ATP production via activation of an AT2-AMPK pathway is required for apoptosis. AMPK also plays an additional role in activation of SHP-2 in an ATP-independent pathway of proapoptotic events. In Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells, we identified mutations of AT2 that inhibit activation of AMPK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Ang II was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Antibodies against caspase 3, cytochrome c, and β-actin were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-SHP-2 (no. 3752), anti-AMPK-α (no. 2603), antiphospho Thr172 AMPK-α (no. 2535), antiphospho Ser79 acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC, no. 3661), and anti-rabbit ACC (no. 3676) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antiphosphotyrosine antibody was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Compound C (6-[4-(2-Piperidin-1-ylethoxy-phenyl)]-3-pyridin-4-yl-pyrrazolo[1,5-a]-pyrimidine), actinomycin D, and oligomycin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-rabbit HA antibody (Y-11) and anti-goat AT2 antibody (C-18) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell culture.

Bovine PAEC were purchased from Cell Applications (San Diego, CA). Passage 2–8 cells were used for all experiments and were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS (Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.5% fungizone (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in a culture incubator. CHO-K1 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and grown according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Plasmid construction, mutagenesis, and expression of AT2 receptors.

Rat AT2 wild-type receptor and the AT2 mutant D90A with HA tags at the NH2 terminus were reported previously (6–8). Rat AT1 receptor with HA tags at the NH2 terminus was previously reported (5). The tC319 lacks the last 44 amino acids in COOH-terminal domain of AT2 from Cys319 (Y. H. Feng, unpublished results). The truncated AT2 mutant HA-tC319-VC and the HA-D90A-VN mutant were prepared by cloning into the phCMV2 vector at the Hind III and Asc I restriction sites, giving either a VN (1–158 aa) or VC (159–239 aa) fragment of Venus fused automatically at the COOH terminus of the proteins. The cloning primers for human AT2 receptors were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) on the basis of the gene sequences of these proteins available in GeneBank. All genes, mutations, and truncated regions were confirmed by gene sequencing (USUHS Molecular Core Facility). Expression of these genes and mutants is determined using Western blot, and functional assays were performed to show that the VN and VC tags did not affect the activity of the AT2 receptors. Five micrograms of the receptor plasmids were introduced in 70% confluent CHO-K1 cells in 24-well plates using the FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Indiana), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

ATP assays.

PAECs were grown to 80% confluency in 35-mm dishes and treated at indicated time points. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS, and 250 μl of ice cold 2.5% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid was added. The cells were scraped from the dish, and the extract was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted 10-fold and neutralized with Tris acetate buffer, pH 7.75. Ten-microliter sample + 100 μl of luciferin-luciferase reagent were used for ATP measurements. ATP assay was then performed using Promega ENLITEN ATP Assay kit following the manufacturer's protocol. According to the manufacturer, the ENLITEN assay uses recombinant luciferase to catalyze the reaction d-Luciferin + ATP + O2 to Oxyluciferin + AMP + PPi + CO2 + light (560 nm), which was measured in a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA). ATP is the limiting component in the reaction, so that the intensity of the emitted light is proportional to ATP concentration.

Cell lysates, mitochondria-free lysates, and immunoprecipitation from PAEC.

To prepare whole cell lysates, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then scraped in 100 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Hepes solution (pH 7.4), 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, 4 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. Cells were placed on ice for 15 min and briefly vortexed. The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (14,000 g, 10 min at 4°C), and the supernatant was used for analysis. Mitochondria extraction was performed using the Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Cultured Cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For immunoprecipitation, equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were incubated with the 1/1,000 (vol/vol) dilution of primary antibody and 1/100 (vol/vol) dilution of GammaBind Plus beads (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) overnight on a rotator at 4°C. The beads were then pelleted by microcentrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and washed twice with fresh lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. For phosphatase assays, Na3VO4 was excluded from the lysis buffer. The final wash buffer was removed, and beads were boiled in 25 μl of fresh Laemmli buffer for 5 min. The beads were vortexed and finally precipitated for 10 min at 14,000 g.

Phosphatase assay.

Immunoprecipitates of SHP-2 were prepared as above and washed three times with the cold lysis buffer (without NA3VO4) and three times with the phosphatase buffer (50 mM Hepes, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). Phosphatase activity was assayed by resuspending the final pellet in a volume of 50 μl of reaction buffer (phosphatase buffer, pH 5.5, 1 mg/ml BSA, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 50 μl of paranitrophenyl phosphate (10 mM) at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with 17 μl of 5 N NaOH, and the absorbance of the samples was measured at 405 nm.

Western blots.

Activation of signal transduction pathways was determined by Western blotting for caspase 3, cytochrome c, AMPK-α, ACC, and β-actin. PAEC were treated at the indicated concentrations of Ang II at varying times. Cell lysates (10 μg of protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE and electroblotted onto 0.45- or 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Blots were blocked with 5% BSA in TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (TTBS) for 1 h at ambient temperature before incubation overnight with 1:1,000 dilution of primary antibody in TTBS/0.5% BSA at 4°C. Blots were washed 3 time with TTBS for 10 min, for 30 min total. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 in TTBS for 1 h; blots were washed in TBS for 3 h. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was applied according to the manufacturer's instructions before exposure with the FujiFilm Image Reader LAS-1000Pro (FujiFilm USA, Valhalla, NY).

Neutral comet assay.

The neutral comet assay utilizes single cell gel electrophoresis to detect internucleosomal DNA cleavage that occurs in apoptosis following the activation of endogenous endonucleases. Cells are electrophoresed in the presence of a detergent that allows the migration of DNA fragments out of the nuclear membrane. Neutral comet assays were performed as previously described (17). Following indicated treatments, PAEC were embedded in 1% agarose and placed on a comet slide (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD). Slides were placed in lysis solution (2.5 M NaCl, 1% Na-lauryl sarcosinate, 100 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris base, 0.01% Triton X-100) for 30 min. The nuclei were subsequently electrophoresed for 10 min at 18 V/cm in 1× Tris/borate/EDTA buffer (0.089 M Tris, 0.089 M boric acid, and 0.002 M EDTA, pH 8.0), fixed in 70% ethanol, and air dried over night. Comets and nuclei were visualized by staining with Sybr Green (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) or propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and viewed on an Olympus FV500 series confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Imaging America, Center Valley, PA) using ×20 magnification at 478-nm excitation, 507-nm emission wavelengths for enhanced green fluorescent protein, and at 535-nm excitation, 617-nm emission wavelengths for propidium iodide. Cells from random fields were scored (100–150 per experiment) and assigned into type A, B, or C categories, on the basis of their tail moments. Type C comets were defined as apoptotic cells as described by Krown et al. (18).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was obtained from PAEC using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm. One microgram of RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed for 10 min at ambient temperature, followed by 30 min at 42°C, in a 20-μl reaction containing 50 U Murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (MuLV-RT) in 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μM oligo-(dT)16, 1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 1 U RNase inhibitor. Samples were heated to 95°C for 10 min to inactivate the MuLV-RT and stored at −20°C. All RT reagents were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). One microgram cDNA from the RT reaction was used in a PCR reaction with 0.4 μM each forward and reverse primer, 200 μM each dNTP and 1 U/50 μl iTaq DNA polymerase and supplied PCR buffer (Bio-Rad). The PCR primers for Bcl-xL ARE-2 mRNA were 5′-ACC TTC CTC AAT TGT CGT GG-3′ and 5′-GGG GAA AAG GGT CAG AAA C-3′. Primers for Bcl-2 ARE were 5′-TGC TTT TGA GGA GGG CTG CAC-3′ and 5′-ACT GCC TGC CAC AGA CCA GC-3′. PCR reactions were optimized for annealing temperatures using a temperature gradient in a Bio-Rad iCycler. Reactions were carried out for 25 cycles using the following conditions: 95°C 1 min; 60°C 45 s; 72°C 1.5 min. The last cycle extension was for 10 min at 65°C. PCR primers for GAPDH were 5′- GAA GCT CGT CAT CAA TGG AAA and 5′- CCA CTT GAT GTT GGC AGG AT. PCR reactions were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel in Tris EDTA buffer, and bands were visualized using ethidium bromide.

Determination of mRNA half-life.

After treatment, PAEC were incubated with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D for time courses. Total RNA was isolated and the level of Bcl-xL mRNA was monitored by qPCR or by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Level of GAPDH mRNA was determined by gel electrophoresis and used for normalization of the semiquantitative RT-PCR. Image J software was used for densitometry (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

RNA-immunoprecipitation.

RNA-immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed as previously described (35) with minor modifications. RNA/protein complexes were cross-linked with 1.0% formaldehyde (vol/vol) for 10 min. Cross-linking was quenched by adding glycine (pH 7.0, 0.125 mol/l final concentration), at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS containing protease inhibitors and a RNase inhibitor and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min. Cell pellet was resuspended in 0.2 ml NP-40 buffer (5 mM PIPES pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP40, protease inhibitors, RNase inhibitor) and incubated on ice for 10 min. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,400 g, 5 min at 4°C. To fragment the mRNA, the supernatant was sonicated three times for 20 s each at output level 6 of a sonic dismembrator, Model 100 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples were cleared by centrifugation for 10 min, 13,000 g at 4°C, and the supernatant was diluted 10-fold into IP buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 167 mM NaCl, protease inhibitors, RNase inhibitor) to a final volume of 1 ml. A 1% aliquot was preserved as an input sample. Nucleolin antibody (1:1,000 dilutions) was added, and samples were rotated at 4°C overnight. To collect immune complexes, 50 μl of Sepharose Beads were added and mixed for 2 h followed by centrifugation at 60 g for 2 min, 4°C. Immune complexes were washed for 5 min with low-salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.1, 150 mM NaCl), high-salt buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.1, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl buffer (0.25M LiCl, 1% NP40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris·HCl pH 8.1), and twice with TE buffer. Each wash was followed by 60 g centrifugation for 1 min. Complexes were eluted in 500 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3, RNase inhibitor). NaCl was added to a final concentration of 200 mM and then placed at 65°C for 2 h to reverse cross-link. A sample (20 μl) of 1 M Tris·HCl, pH 6.5, 10 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, and 20 μg of Proteinase K were added and incubated at 42°C for 45 min. RNA was extracted using phenol:chloroform and glycogen as a DNA carrier. DNA was removed by DNase (Qiagen). RT-PCR was performed using 1 μl of the cDNA reaction for 25 cycles; denaturing was performed at 95°C for 1 min, annealing for 45 s at 60°C, and polymerase reaction for 1.5 min at 72°C.

Statistical analysis.

Means ± SD were calculated, and statistically significant differences between two groups were determined by the Student's t-test. For three or more groups, statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc analysis, as appropriate; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Ang II induces ATP generation by AMPK.

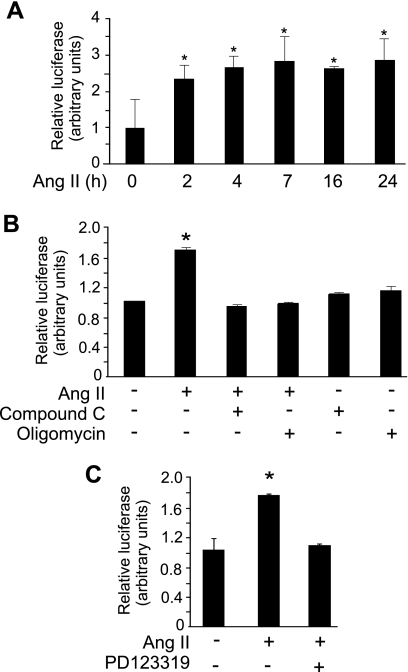

The execution of apoptosis requires ATP at several steps (14, 24, 33, 46), but it is unknown whether ATP generation above basal levels is required for Ang II-induced apoptosis. Stimulation of AT2 in PAEC induced ATP generation by 2.5-fold, detectable within 2 min of treatment; the increase in ATP levels was sustained for 24 h (Fig. 1A). The time course of induction of ATP suggested the activation of a rapid signal transduction pathway for the generation of ATP. We investigated the requirement of AMPK for ATP generation by Ang II. Addition of the specific AMPK inhibitor compound C abrogated Ang II-induced ATP increase but did not reduce ATP below basal levels (Fig. 1B). As a control, we showed that ATP generation was also inhibited by treatment of cells with oligomycin (Fig. 1B). PAEC express both AT1 and AT2 receptors of Ang II, and previous data from our laboratory showed that Ang II-induced apoptosis in PAEC is mediated by the AT2 receptor (20). We found that the AT2-specific antagonist PD123319 blocked the Ang II-induced increase of ATP production in PAEC (Fig. 1C). Addition of PD123319 alone had no effect on basal ATP levels (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Increase of ATP production induced by angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2) stimulation. Pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) were grown to 80% confluence and placed in 0.1% FBS/RPMI overnight before treatment with angiotensin II (Ang II) (10 μM). Relative ATP levels were measured. A: Ang II was added for the indicated times. B: Ang II-induced ATP productions were assayed after 2 h in the presence and absence of compound C (40 μM) or oligomycin (50 nM). Compound C or oligomycin was added 20 min before Ang II. C: Ang II AT2 receptor antagonist PD123319 (50 μM) was added 20 min before the addition of Ang II for 2 h. All data show means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with control, experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Ang II activates AMPK via the AT2 receptor.

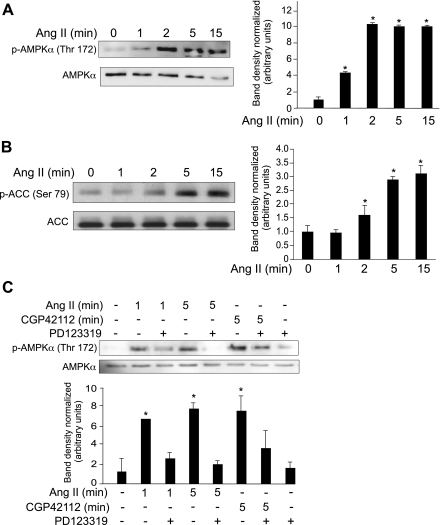

To understand the mechanism of Ang II-induced ATP generation during apoptosis, we investigated the activation of AMPK in primary PAEC. Treatment of PAEC with Ang II resulted in ∼10-fold increase in phosphorylation of AMPK-α within 2 min (Fig. 2A). ACC, a downstream target of AMPK, is used as an indication of AMPK activation (9). Treatment of PAEC with Ang II increased ACC phosphorylation approximately twofold, detectable within 15 min (Fig. 2B). We found that PD123319, an AT2-specific inhibitor, blocked Ang II activation of AMPK (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the AT2-specific agonist CGP42112 that induces apoptosis (20) also activated AMPK-α phosphorylation to the same degree as Ang II (Fig. 2C). These findings provide evidence that Ang II activates AMPK through the AT2 receptor.

Fig. 2.

Ang II activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in PAEC downstream of the AT2 receptor. PAEC were grown to 80% confluence and placed in 0.1% FBS/RPMI overnight before treatment with Ang II (10 μM) for the indicated times. A: cell lysates were prepared, and equal amounts of protein were used for Western blotting for phosphorylated AMPK (pAMPK, top). Blots were stripped and reprobed for total AMPK as a loading control (bottom). Bar graph indicates p-AMPK-α band density normalized total AMPK-α band density. B: equal amounts of protein Western blotted for phosphorylated acetyl CoA carboxylase (pACC, top). The blot was stripped and reprobed with total ACC as a loading control (bottom). Bar graph indicates band density of pACC normalized total ACC band density. C: before treatment with Ang II, cells were treated with the AT2 antagonist PD123319 (50 μM) for 20 min. Alternatively, PAEC were treated with the AT2 agonist CGP42112 (10 μM). Lysates were prepared, and equal amounts of protein were used for Western blotting for pAMPK (top). Blots were stripped and probed for total AMPK (bottom). Bar graph (below data) indicates normalized band density for pAMPK. All data show means ± SD. *Indicates statistical significance from control, P < 0.05, n = 3. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Active ATP generation is required for Ang II-induced apoptosis, cytochrome c release, and caspase 3 activation.

We investigated the link between ATP generation and induction of apoptosis. When Ang II-induced ATP generation was blocked in PAEC by oligomycin treatment, Ang II-induced apoptosis was significantly blocked as determined using the neutral comet assay (Fig. 3A). Although oligomycin alone induced ∼30% apoptosis, this was significantly lower than the level of apoptosis induced by Ang II alone (∼80%).

Fig. 3.

ATP generation and AMPK are required for Ang II-induced apoptosis in PAEC. A and B: PAEC were grown to 80% confluence and placed in 0.1% FBS/RPMI overnight. Neutral comet assays were performed to detect apoptotic cells. Percentage of apoptotic cells were then determined. A: cells were treated with oligomycin (50 nM) for 1 h in glucose-free medium (RPMI, 0% FBS). Cells were washed twice in 10% FBS/RPMI before the addition of Ang II (10 μM) for 16 h. B: cells were treated with and without the AMPK inhibitor compound C (40 μM). C: mitochondria-free cell lysates were Western blotted for active cytochrome c and caspase 3. Blots were stripped and probed for β-actin as a loading control. Representative results are shown. Bar graphs represent normalized band densities for both cytochrome c and activated caspase 3. All bar graphs show means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with control, †P < 0.05 compared with Ang II treatment, n = 3. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Ang II-induced apoptosis involves the activation of caspase 3 and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria (20). Our data indicated that Ang II-induced apoptosis is ATP dependent and that Ang II activates AMPK. Thus we hypothesized that AT2-induced apoptosis might be AMPK dependent. Compound C, an AMPK-specific inhibitor, inhibited AT2-induced apoptosis, as determined using neutral comet assays (Fig. 3B). Ang II treatment induced approximately threefold increase in caspase 3 level and a ∼1.6-fold increase cytochrome c in the cytoplasm compared with the untreated control. Inhibition of AMPK blocked both caspase 3 activation and cytochrome c release from the mitochondria to basal levels (Fig. 3C). We also found that oligomycin treatment inhibited caspase 3 activation and cytochrome c release from the mitochondria (data not shown).

AT1 and AT2 receptor overexpression activates AMPK; AT2 activation of AMPK requires the active conformation and the COOH-terminal domain in surrogate CHO-K1 cells.

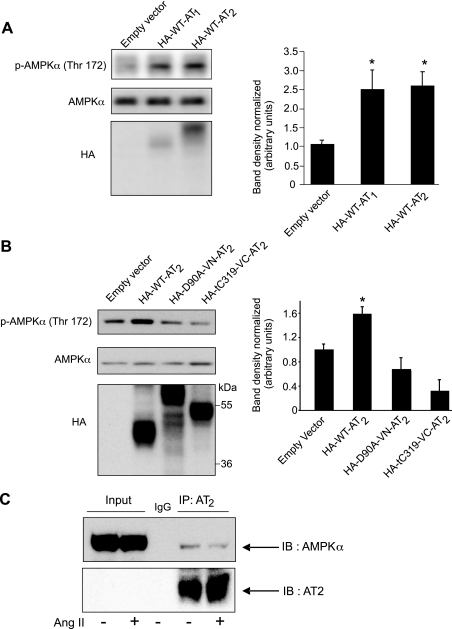

Activation of AMPK by both AT1 and AT2 was investigated by immunoblotting for Thr172 phosphorylation following exogenous overexpression of the receptors in CHO-K1 cells. The cell surface expression of wild-type and mutant AT receptors and their binding of 125I-Ang II ligand was previously reported (6–8). In mock transfections using an empty vector, a low level of activated AMPK was already present in the CHO-K1 cell line (Fig. 4A). In agreement with previous studies demonstrating that AT1 activates AMPK in vascular smooth muscle cells (27), we found that overexpression of AT1 in the absence of added Ang II was sufficient to activate AMPK in CHO-K1 cells ∼2.5-fold (Fig. 4A). Likewise, overexpressing wild-type AT2 increased AMPK phosphorylation ∼2.5-fold in the absence of Ang II (Fig. 4A); the addition of Ang II at concentration as high as 10 μM did not further increase AMPK phosphorylation (data not shown). This finding was consistent with previous results indicating that AT2 is constitutively active when overexpressed (7, 8).

Fig. 4.

AT2-mediated activation of AMPK in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cells. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with control plasmid (empty vector) or with wild-type (HA-WT, 41.3 kDa) or mutant AT2 receptors (HA-D90A-VN, 59.5 kDa, or HA-tC319-VC, 45.5 kDa). A: activation of AMPK in the presence of transfected control (empty vector) or WT AT1 or WT AT2 for 36 h. B: activation of AMPK by AT2 HA-WT and mutants. Phosphorylation of AMPK-α and total AMPK-α were detected 36 h after transfection. Lower blot shows levels of expression of the AT2 WT and mutants at levels comparable. Bar graphs show means ± SD, n = 3; *P < 0.01 from control. Experiments were repeated 3 times. C: coimmunoprecipitation of AMPK with AT2. Whole cell lysates (500 μg) from PAEC either untreated or treated for 15 min with Ang II (10 μM) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-AT2. Immunoprecipitates were Western blotted for AMPK-α (top) or for AT2 (bottom). IgG was used as a nonspecific antibody as a control for immunoprecipitation. IB, immunoblot.

To determine what regions of AT2 are required for AMPK activation, we examined AMPK activation by mutant AT2 receptors. The mutant D90A is paralyzed in ligand-induced conformational change and maintains the inactive conformation (7). The truncation mutant tC319 lacks the last 44 amino acids of the cytoplasmic COOH-terminal domain. The mutant receptors D90A and tC319 bound agonist Ang II and antagonist PD123319 with affinity similar to that of the wild-type (7) (Y. H. Feng, unpublished findings). No significant differences in expression levels were observed among AT2 receptors (Fig. 4B). Both AT2 receptor mutants failed to activate AMPK-α (Fig. 4B). These data suggest that the active conformation of the receptor is required for AMPK activation and that the COOH-terminal domain of AT2 is essential for AMPK activation.

We investigated the direct association between AT2 and AMPK using coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous AT2 and AMPK in PAEC. Data indicate that the α-subunit of AMPK coimmunoprecipitates with AT2 (Fig. 4C). Ang II treatment for 15 min (a time point at which AMPK is activated) slightly reduced the association between the two proteins (Fig. 4C). Note that AT2 is difficult to detect in PAEC without immunoprecipitation because endogenous levels of expression are low.

AMPK is required for Ang II activation of SHP-2 and for Bcl-xL mRNA destabilization.

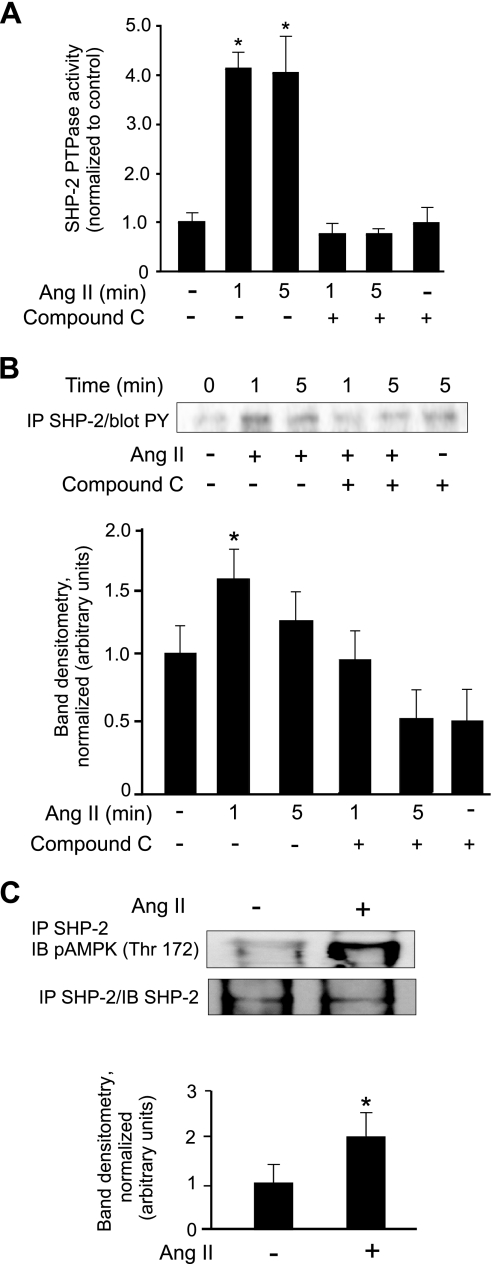

We previously showed in PAEC that SHP-2 phosphorylation and activation are required for AT2-induced apoptosis (20). We investigated the possibility that AMPK might play a signal transduction role independent of energy generation by activating SHP-2. Treatment of PAEC with Ang II induced a fourfold increase in SHP-2 phosphatase activity (Fig. 5A). Treatment with the AMPK inhibitor compound C before the addition of Ang II completely inhibited AT2 activation of SHP-2 phosphatase (Fig. 5A) and blocked tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-2 (Fig. 5B). Treatment of PAEC with Ang II for 1 min induced the association of SHP-2 with AMPK as shown by coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblot experiments (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Src-homology two-domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2) activation by Ang II requires AMPK. PAEC were grown to 80% confluence and placed in 0.1% FBS/RPMI overnight. A and B: PAEC were treated with Ang II (10 μM) for the indicated times. Cells were pretreated with or without the AMPK inhibitor compound C (40 μM) for 20 min. A: equal amounts of protein from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-SHP-2. Immunoprecipitated SHP-2 protein was then subjected to phosphatase assays. B: equal amounts of protein were used for SHP-2 immunoprecipitation and blotted for tyrosine phosphorylation. Lower panel shows densitometry of phospho-SHP-2 bands. C: PAEC were treated with 10 μM Ang II for 5 min before preparation of cell lysates. Equal amounts of protein were used for SHP-2 immunoprecipation. Immunoprecipitated protein was then Western blotted for phospho-AMPK (top) or for SHP-2 (bottom). Lower bar graph indicates phospho-AMPK band density normalized to SHP-2 band density. All data show means ± SD. *Indicates statistical significance from control, P < 0.05, n = 3. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

Because we previously found that SHP-2 activation was required for the observed decrease in the Bcl-xL mRNA half-life by Ang II (20), we investigated whether AMPK was also required upstream for AT2-induced destabilization of the Bcl-xL mRNA. Ang II induced a 10-fold decrease in the level of Bcl-xL mRNA at 6 h after the addition of actinomycin D (Fig. 6A). Pretreatment of PAEC with compound C completely prevented AT2 destabilization of Bcl-xL mRNA. As a control, we demonstrated that the stability of GAPDH mRNA was not affected by AT2 upon Ang II stimulation, and its half-life was not altered (Fig. 6A, bottom).

Fig. 6.

AMPK is required for Ang II-induced effects on Bcl-xL mRNA. PAEC were grown to 80% confluence and placed in 0.1% FBS/RPMI overnight. A: cells were treated with 10 μM Ang II with or without pretreatment with compound C (40 μM) for 20 min. After 8 h, cells were treated with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D for the indicated times. Cellular mRNA was prepared, and PCR was performed for Bcl-xL or GAPDH as a control. Bottom: Ang II-induced downregulation of Bcl-xL mRNA. ○, PAEC controls; ■, PAEC treated with Ang II; ●, treatment with both compound C and Ang II; and □ indicate treatment with compound C alone. Densitometry data was normalized to the zero time point for control. Data show means ± SD. *Indicates statistical significance from control, P < 0.05, n = 3. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times. B: disassociation of nucleolin from Bcl-xL mRNA. RNA-IP of mRNA was performed for nucleolin as described in materials and methods. Input control shows RT-PCR of Bcl-xL. Bcl-xL mRNAs were detected in all samples of RNA-IP with control IgG as negative controls. Graph indicates means ± SD, n = 3. C: cells were treated with 10 μM Ang II with or without 1-h pretreatment with oligomycin (50 nM). After 8 h, cells were treated with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D for the indicated times. Cellular mRNA was prepared and PCR was performed for Bcl-xL or GAPDH as a control, as described in A. ○, PAEC controls; ■, PAEC treated with Ang II; ●, treatment with both oligomycin (oligo) and Ang II, □, treatment with oligomycin alone. Densitometry data was normalized to the zero time point for control. Data show means ± SD. *Indicates statistical significance from control, P < 0.05, n = 3. Experiments were repeated at least 3 times.

We previously showed that Ang II-induced loss of Bcl-xL mRNA was accompanied by reduced binding of Bcl-xL mRNA to nucleolin, a protein that binds the 3′UTR and prevents degradation signaled by an ARE (20). We determined that nucleolin dissociation from the Bcl-xL mRNA required SHP-2 activation by Ang II (19). We investigated the effect of AMPK inhibition on Ang II-induced disassociation of nucleolin from Bcl-xL mRNA using RNA immunoprecipitation experiments. Ang II treatment resulted in an ∼70% reduction of nucleolin association with Bcl-xL mRNA. Consistent with the role of AMPK in SHP-2 regulation, pretreatment of PAEC with the AMPK inhibitor preserved nucleolin binding to the Bcl-xL mRNA (Fig. 6B). We previously showed that Ang II had no effect on nucleolin binding to Bcl-2 mRNA, and treatment with the AMPK inhibitor also had no effect on nucleolin binding to Bcl-2 mRNA (Fig. 6B).

To determine whether ATP generation is also required for Ang II-induced decrease in the Bcl-xL mRNA half-life, we used oligomycin to block ATP generation in PAEC. In the absence of ATP generation, the effect of Ang II on Bcl-xL mRNA degradation is not observed (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to determine the requirement of AMPK for the execution of AT2-mediated apoptosis. We found that ATP generation is required for Ang II-induced apoptosis and that the generation of ATP requires AMPK activation. We provide evidence that AMPK is also required for energy-independent signaling for Ang II-induced apoptosis, for the activation of SHP-2, and subsequent destabilization of the Bcl-xL mRNA half-life through reduced binding to nucleolin. Thus AMPK activation by Ang II leads to a novel combination of ATP-dependent and -independent signaling, both of which are required for apoptosis.

In a variety of cell types including some primary cells, AT2 has been shown to activate signaling pathways leading to growth inhibition or apoptosis (1, 37, 39, 40, 43). AT2 induces apoptosis in PC12W cells (12, 44), CHO epithelial cells (25), A7r5 vascular smooth muscle cells (25), and primary epithelial and endothelial cells (20, 39). In cells containing only endogenously expressed Ang II receptors, the addition of Ang II is required for apoptotic signaling through the AT2 receptor. In contrast, when the AT2 receptor is overexpressed, Ang II ligand is not required for apoptosis (25). Overexpression studies revealed that AT2-induced apoptosis is dependent on the formation of constitutively active AT2 homodimers (26). This is consistent with our current finding that AMPK activation is independent of Ang II in CHO-K1 overexpressing AT2.

In agreement with previous findings showing that AT1 activates AMPK in vascular smooth muscle cells (27), we found that overexpression of AT1 was sufficient to activate AMPK in CHO-K1 cells. Our pharmacological data indicate that the inhibition of AT2 was sufficient to block AMPK activation by Ang II and that activation of AT2 using a specific agonist was sufficient to activate AMPK. We also demonstrate that AT2 associates with the α-subunit of AMPK. It is possible that endogenous AT1 in PAEC also activates AMPK simultaneously. Additional studies are required to show that AMPK activation by AT2 does not require the presence of AT1.

We investigated the activation of AMPK by two AT2 mutants. GPCRs can have multiple conformational states, and mutations at critical positions of a GPCR alter the conformation of the receptor and properties such as trafficking and localization (5, 29). Mutations at D90 in AT2 result in defects in attaining the active conformation (7). The failure of the AT2 receptor mutant D90A to activate AMPK suggests that there may be a role for receptor conformation in regulating the receptor/AMPK interaction. The tC319 AT2 receptor mutant lacking the last 44 amino acids of COOH-terminal domain also fails to activate AMPK, suggesting that this cytoplasmic region is important for protein-protein interactions leading to AMPK activation. The details of the protein-protein interactions between AT2 and AMPK are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

The mechanism by which AT2 induces phosphorylation of the AMPK α-subunits is unknown because AT2 lacks kinase activity. Activation of AMPK via LKB1 was shown to occur via the adenylate cyclase activation by other Gαs-coupled GPCRs (13), but we hypothesize that this mechanism is not responsible for AMPK activation in our system because we previously determined that Gαs activation was not required for AT2-induced SHP-2 activation or for apoptosis. We hypothesize that another adaptor or kinase may also be involved. AMPK associates with the adaptor protein growth factor receptor-bound protein 2, which has been demonstrated to bind a variety of tyrosine kinase receptors and downstream signaling proteins. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the activation mechanism and the potential involvement of other kinases of AMPK.

The requirement of AMPK for energy-dependent and -independent mechanisms of apoptosis has not been previously demonstrated. Multiple steps during the apoptotic process have been identified that require ATP, including the formation of the apoptosome complex (comprised of cytoplasmic cytochrome c, Apaf 1 and procaspase 9), chromatin condensation, apoptosis-associated gene expression, and active nuclear transport (14, 24, 33, 46). The concept of ATP generation exclusively for execution of apoptosis (apoptosis-specific ATP) in response to a death signal will require further investigation. Our findings suggest that AMPK plays a central role for both energy-dependent and -independent mechanisms in Ang II signaling by acting as a converging point.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH grant (HL065492) to Y.-H. Feng, by NIH grant HL-073929 and a USUHS research grant to R. M. Day, and by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association to Y. H. Lee.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Current address for Y. Lee: Urologic Oncology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Current address for L. Han: Department of Medical Microbiology, China Three Gorges University School of Medicine, Yichang, Hubei, China. The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, official policy, or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Federal Government. Some of the authors are employees of the U.S. Government, and this manuscript was prepared as part of their official duties.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bedecs K, Elbaz N, Sutren M, Masson M, Susini C, Strosberg AD, Nahmias C. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors mediate inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and functional activation of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase. Biochem J 325: 449–454, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen MB, Shen WX, Yang Y, Wu XY, Gu JH, Lu PH. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase is involved in vincristine-induced cell apoptosis in B16 melanoma cell. J Cell Physiol 226: 1915–1925, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen MB, Wu XY, Gu JH, Guo QT, Shen WX, Lu PH. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase contributes to doxorubicin-induced cell death and apoptosis in cultured myocardial H9c2 cells. Cell Biochem Biophys 60: 311–322, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev 52: 415–472, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng YH, Miura S, Husain A, Karnik SS. Mechanism of constitutive activation of the AT1 receptor: influence of the size of the agonist switch binding residue Asn(111). Biochemistry 37: 15791–15798, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feng YH, Saad Y, Karnik SS. Reversible inactivation of AT(2) angiotensin II receptor from cysteine-disulfide bond exchange. FEBS Lett 484: 133–138, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feng YH, Sun Y, Douglas JG. Gbeta gamma -independent constitutive association of Galpha s with SHP-1 and angiotensin II receptor AT2 is essential in AT2-mediated ITIM-independent activation of SHP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 12049–12054, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng YH, Zhou L, Sun Y, Douglas JG. Functional diversity of AT2 receptor orthologues in closely related species. Kidney Int 67: 1731–1738, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hardie DG. AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 774–785, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardie DG, Carling D, Carlson M. The AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinase subfamily: metabolic sensors of the eukaryotic cell? Annu Rev Biochem 67: 821–855, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higuchi S, Ohtsu H, Suzuki H, Shirai H, Frank GD, Eguchi S. Angiotensin II signal transduction through the AT1 receptor: novel insights into mechanisms and pathophysiology. Clin Sci (Lond) 112: 417–428, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horiuchi M, Hayashida W, Kambe T, Yamada T, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin type 2 receptor dephosphorylates Bcl-2 by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem 272: 19022–19026, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutchinson DS, Summers RJ, Bengtsson T. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase activity by G-protein coupled receptors: potential utility in treatment of diabetes and heart disease. Pharmacol Ther 119: 291–310, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kass GE, Eriksson JE, Weis M, Orrenius S, Chow SC. Chromatin condensation during apoptosis requires ATP. Biochem J 318: 749–752, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim YM, Hwang JT, Kwak DW, Lee YK, Park OJ. Involvement of AMPK signaling cascade in capsaicin-induced apoptosis of HT-29 colon cancer cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 1095: 496–503, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kishi K, Yuasa T, Minami A, Yamada M, Hagi A, Hayashi H, Kemp BE, Witters LA, Ebina Y. AMP-Activated protein kinase is activated by the stimulations of G(q)-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 276: 16–22, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kitta K, Day RM, Ikeda T, Suzuki YJ. Hepatocyte growth factor protects cardiac myocytes against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 31: 902–910, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krown KA, Page MT, Nguyen C, Zechner D, Gutierrez V, Comstock KL, Glembotski CG, Quintana PJE, Sabbadini RA. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes: involvement of the sphingolipid signaling cascade in cardiac cell death. J Clin Invest 98: 2854–2865, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee YH, Marquez AP, Mungunsukh O, Day RM. Hepatocyte growth factor inhibits apoptosis by the profibrotic factor angiotensin II via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 in endothelial cells and tissue explants. Mol Biol Cell 21: 4240–4250, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee YH, Mungunsukh O, Tutino RL, Day RM. Angiotensin II-induced apoptosis requires SHP-2 regulation of nucleolin and Bcl-xL in primary lung endothelial cells. J Cell Sci 123: 1634–1643, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee YK, Hwang JT, Kwon DY, Surh YJ, Park OJ. Induction of apoptosis by quercetin is mediated through AMPKalpha1/ASK1/p38 pathway. Cancer Lett 292: 228–236, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee YK, Park SY, Kim YM, Park OJ. Regulatory effect of the AMPK-COX-2 signaling pathway in curcumin-induced apoptosis in HT-29 colon cancer cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 1171: 489–494, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li J, Yan B, Huo Z, Liu Y, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang D, Peng L, Zhang Y, Zhou ZN, Shi J, Cui J, Chen YH. Beta2- but not beta1-adrenoceptor activation modulates intracellular oxygen availability. J Physiol 588: 2987–2998, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 86: 147–157, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miura S, Karnik SS. Ligand-independent signals from angiotensin II type 2 receptor induce apoptosis. EMBO J 19: 4026–4035, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miura S, Karnik SS, Saku K. Constitutively active homo-oligomeric angiotensin II type 2 receptor induces cell signaling independent of receptor conformation and ligand stimulation. J Biol Chem 280: 18237–18244, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nagata D, Takeda R, Sata M, Satonaka H, Suzuki E, Nagano T, Hirata Y. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits angiotensin II-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation 110: 444–451, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakatsu Y, Kotake Y, Hino A, Ohta S. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by tributyltin induces neuronal cell death. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 230: 358–363, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perez DM, Karnik SS. Multiple signaling states of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Rev 57: 147–161, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Porrello ER, Delbridge LM, Thomas WG. The angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptor: an enigmatic seven transmembrane receptor. Front Biosci 14: 958–972, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanders MJ, Grondin PO, Hegarty BD, Snowden MA, Carling D. Investigating the mechanism for AMP activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Biochem J 403: 139–148, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scott JW, Ross FA, Liu JK, Hardie DG. Regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by a pseudosubstrate sequence on the gamma subunit. EMBO J 26: 806–815, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh S, Khar A. Differential gene expression during apoptosis induced by a serum factor: role of mitochondrial F0–F1 ATP synthase complex. Apoptosis 10: 1469–1482, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steckelings UM, Kaschina E, Unger T. The AT2 receptor—a matter of love and hate. Peptides 26: 1401–1409, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun BK, Deaton AM, Lee JT. A transient heterochromatic state in Xist preempts X inactivation choice without RNA stabilization. Mol Cell 21: 617–628, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Towler MC, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase in metabolic control and insulin signaling. Circ Res 100: 328–341, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uhal BD, Gidea C, Bargout R, Bifero A, Ibarra-Sunga O, Papp M, Flynn K, Filippatos G. Captopril inhibits apoptosis in human lung epithelial cells: a potential antifibrotic mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L1013–L1017, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viollet B, Athea Y, Mounier R, Guigas B, Zarrinpashneh E, Horman S, Lantier L, Hebrard S, Devin-Leclerc J, Beauloye C, Foretz M, Andreelli F, Ventura-Clapier R, Bertrand L. AMPK: Lessons from transgenic and knockout animals. Front Biosci 14: 19–44, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang R, Alam G, Zagariya A, Gidea C, Pinillos H, Lalude O, Choudhary G, Oezatalay D, Uhal BD. Apoptosis of lung epithelial cells in response to TNF-alpha requires angiotensin II generation de novo. J Cell Physiol 185: 253–259, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang R, Zagariya A, Ang E, Ibarra-Sunga O, Uhal BD. Fas-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells requires ANG II generation and receptor interaction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L1245–L1250, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Witczak CA, Sharoff CG, Goodyear LJ. AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle: from structure and localization to its role as a master regulator of cellular metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci 65: 3737–3755, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wong KA, Lodish HF. A revised model for AMP-activated protein kinase structure: The alpha-subunit binds to both the beta- and gamma-subunits although there is no direct binding between the beta- and gamma-subunits. J Biol Chem 281: 36434–36442, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xoriuchi M, Hamai M, Cui TX, Iwai M, Minokoshi Y. Cross talk between angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors: cellular mechanism of angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated cell growth inhibition. Hypertens Res 22: 67–74, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yamada T, Horiuchi M, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor mediates programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 156–160, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yang D, Yaguchi T, Nakano T, Nishizaki T. Adenosine Activates AMPK to phosphorylate Bcl-X(L) responsible for mitochondrial damage and DIABLO release in HuH-7 cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 27: 71–78, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yasuhara N, Eguchi Y, Tachibana T, Imamoto N, Yoneda Y, Tsujimoto Y. Essential role of active nuclear transport in apoptosis. Genes Cells 2: 55–64, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]