Abstract

Objective

Childhood externalizing behavior is found to be relatively persistent. Developmental pathways within types of externalizing behavior have been recognized from childhood to adolescence. We aimed to describe the prediction of adult DSM-IV disorders from developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior over a period of 24 years on a longitudinal multiple birth cohort study of 2,076 children. This has not been examined yet.

Methods

Trajectories of the four externalizing behavior types aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations were determined separately through latent class growth analysis (LCGA) using data of five waves, covering ages 4–18 years. Psychiatric disorders of 1,399 adults were assessed with the CIDI. We used regression analyses to determine the associations between children’s trajectories and adults’ psychiatric disorders.

Results

All externalizing behavior types showed significant associations with disruptive disorder in adulthood. In all antisocial behavior types high-level trajectories showed the highest probability for predicting adult disorders. Particularly the status violations cluster predicted many disorders in adulthood. The trajectories most often predicted disruptive disorders in adulthood, but predicted also anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders.

Conclusions

We can conclude that an elevated level of externalizing behavior in childhood has impact on the long-term outcome, regardless of the developmental course of externalizing behavior. Furthermore, different types of externalizing behavior (i.e., aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations) were related to different adult outcomes, and children and adolescents with externalizing behavior of the status violations subtype were most likely to be affected in adulthood.

Keywords: Externalizing behavior, DSM-IV, Developmental pathways

Introduction

It is well established in the literature that externalizing behavior in childhood and adolescence is associated with a wide range of poor concurrent and longitudinal outcomes [1]. Regarding longitudinal outcomes, studies report that children and adolescents with externalizing behavior problems are at risk for a wide range of disorders in adulthood that include: disruptive behavior [2–7], mood and anxiety problems [8–11], and substance use and abuse [5, 9, 12].

However, because externalizing behavior is an umbrella concept encompassing several different kinds of behavior, Frick et al. [13] performed a meta-analysis of 44 published studies and empirically divided externalizing behavior into four types: aggression (e.g., fights, bullies), oppositionality (e.g., temper, stubborn), property violations (e.g., lies, cruel to animals), and status violations (e.g., substance use, runaway). To our knowledge, only two studies have examined the adult outcome of types of externalizing behavior problems as suggested by Frick and colleagues [13]. These studies underline the need to distinguish between types of externalizing behavior, that is, they report that status violations predict substance use and social impairment, that oppositionality only predicts social impairment, whereas property violations and aggression predict both substance use and risky sexual behavior [15, 16].

Regarding development of externalizing behavior, previous studies have provided evidence for variation in developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior in childhood and adolescence with most studies identifying four to six distinctive trajectories [17–19]. Developmental trajectories describe changes in both the level and the growth or decline of behaviors over time [20]. It is important to know which change in level and growth across age may be considered normative for children and adolescents. Because from both theoretical and clinical perspective, it is indispensable to understand normal development for defining abnormal behavior at any age point. In the previous study that examined the development of the four externalizing behavior types suggested by Frick et al. [13] from early childhood up to young adulthood (i.e., from age 4 to age 18) the following developmental trajectories were identified: three trajectories for aggression ranging from very low to high, six trajectories for oppositionality ranging from very low to high and including a trajectory where oppositionality increased in adolescence, and four trajectories for property and status violation ranging from low to high [21]. Considering these different developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior that groups of children follow, it is important to examine groups of children that follow developmental trajectories that vary in level and shape, because an average developmental trajectory that describes expected development for most children may be considered insufficient. In the current study, we determined distinctive groups of individuals who are more likely to follow one developmental trajectory than another, within each type of externalizing behavior.

In the study by Bongers et al. [21], status violations was the only externalizing behavior type that increased with age, whereas the remaining types primarily showed a persisting or decreasing course. In a more recent study by Bongers et al. [15], in which the relation of both level and growth of externalizing problems, as suggested by Frick et al. [13], to adult outcomes was examined, primarily the level of the trajectories was found to be predictive. Children with high-level trajectories of opposition and status violations reported more impaired social functioning, regardless of the direction, or growth, or decline of these high-level trajectories. However, in the study by Timmermans et al. [16] both the level and growth of opposition, aggression, and property violations were related to poor adolescent outcomes such as risky sexual behavior and substance use. In this latter study only the level of status violations predicted later negative outcomes. Hence, findings are inconclusive as to how developmental trajectories of these externalizing behavior types are related to other long-term outcomes, and further research on this issue is needed.

In this study, we aimed to investigate associations between childhood externalizing behavior and adult psychopathology. We examined the prediction of adult DSM-IV disorders from developmental trajectories of the four types of externalizing behavior suggested by Frick et al. [13] (i.e., opposition, aggression, property violations, and status violations) over a period of 24 years in a longitudinal, multiple birth cohort study of 2,076 children from the general population. Because studies have reported prognostic differences between the four types of childhood externalizing behavior as suggested by Frick et al. [13], we investigated the linkage between childhood externalizing behavior and adult psychopathology, distinguishing these types of externalizing behavior. In addition, although previous studies reported outcomes for the four externalizing behavior types up to young adulthood (i.e., age 18 in the study by Timmermans et al. [16]; up to age 30 in the study by Bongers et al. [15]), knowledge about their outcome beyond young adulthood is lacking. Therefore, we aimed to extend the findings of Bongers et al. [15], which are based on a previous wave of the current study, by examining the prediction of developmental trajectories in middle adulthood (i.e., from age 28 to 40 years).

Based on earlier findings, we expect that an elevated level of externalizing behavior in childhood has impact on the long-term outcome, in addition to the developmental course of externalizing behavior [5, 8, 11, 15, 22, 23]. Furthermore, we expect that different types of externalizing behavior (i.e., aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations) are related to different adult outcomes [15, 16]. Finally, according to the fact that the oppositional and status violations type consist of more reactive and nondestructive behaviors, these types of problems are expected to develop into emotional problems. Because the property violations and aggression type consist of proactive, destructive behaviors, these types are expected to develop into behavior problems in adulthood [24, 25]. Because behavior problems of the status violations type have been found to increase with age [21], we expect that this type is associated with most adult problems.

Methods

Sample

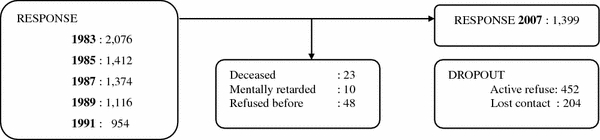

In 1983, a sample of 2,600 children aged 4–16 years was randomly selected from the general population of the Dutch province of Zuid-Holland. A hundred children of each gender and age were drawn from the municipal registers listing all residents in the province A total of 2,447 parents of child participants could be reached, of whom 2,076 (84.8%) completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) on their child. Parents were interviewed at 2-year intervals until 1991 and the participants themselves were interviewed in 2006 and 2007 when they were 28–40 years old. We approached all participants from the original sample, except 23 who had died, 10 who were intellectually disabled, and 48 who had requested to be removed from the sample at an earlier stage of the study [26]. We reached 1,791 of the 1,995 participants, 452 refused and 1,339 respondents provided information for determining DSM-IV diagnoses, see Fig. 1. The response rate in the seventh data collection was 66% (1,339 of 2,043).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the data collection between 1983 and 2007

To investigate selective attrition, we performed logistic regression analyses to look at associations between age, gender, socio-economic status (SES), and Total Problems Score of participants in 1983, and participation in 2006 and 2007. SES was scored on a six-step scale of parental occupation [27] with 1 = lowest SES. Total Problems Score was calculated by summing 118 of the specific item scores on emotional and behavioral problems in the CBCL. Although age, gender, and SES had significant influence on participation at follow-up, the differences were small. Participation was more likely when participants were women (51.1% for dropouts versus 53.7% for participants; OR = 1.33; CI 1.11–1.60; p < 0.002), if they were younger (mean age at baseline was 10.2 years for dropouts and 9.8 years for participants; OR = 0.97; CI 0.95–1.00; p < 0.026), and had a higher SES (3.4 for dropouts and 3.7 for participants; OR = 1.12; CI 1.06–1.19; p < 0.000). No influence on participation was found for Total Problems Score.

Measurements

Externalizing behavior trajectories

From 1983 to 1991 the CBCL was used to obtain standardized parent reports of children’s problem behaviors. Externalizing behavior trajectories were based on assessment with the CBCL. The CBCL is a rating scale intended for completion by parents of 4–18-year-old children; it contains 120 items covering behavioral or emotional problems that have occurred during the past 6 months. The items are scored on a three-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). The reliability and validity of the CBCL [28] have been confirmed for the Dutch version [29].

We selected 21 externalizing behavior items of the CBCL, corresponding to items that Frick et al. [13] used for the classification of antisocial behavior into four types which are: aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations (Table 1). The structure of the four types was confirmed with confirmatory factor analyses. The average goodness-of-fit index (GFI) across time 1–time 5 was 0.92 for males and 0.96 for females [21].

Table 1.

Item description of the four externalizing behavior types

| Frick cluster | Child behavior checklist item |

|---|---|

| Aggression | Cruelty, bullying, or meanness to others |

| Gets in many fights | |

| Physically attacks people | |

| Threatens people | |

| Opposition | Argues a lot |

| Disobedient at home | |

| Disobedient at school | |

| Stubborn, sullen, or irritable | |

| Sulks a lot | |

| Teases a lot | |

| Temper tantrums or hot temper | |

| Property violations | Cruel to animals |

| Lying or cheating | |

| Sets fires | |

| Steals at home | |

| Steals outside the home | |

| Vandalism | |

| Status violations | Runs away from home |

| Swearing or obscene language | |

| Truancy, skips school | |

| Uses alcohol or drugs for not medical purposes |

CBCL items to which the content showed a good match to the description provided by the authors of the types [13] that were clustered to form four types of externalizing behavior

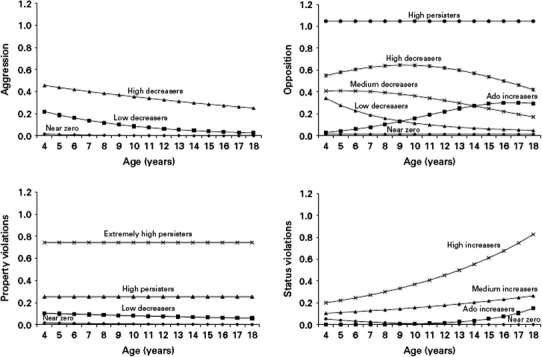

Trajectories of externalizing behavior for ages 4–18 years were identified in a previous study on the Zuid-Holland data (see Fig. 2) [21]. A semi-parametric, group-based approach [20] was used to determine developmental trajectories of the four externalizing behavior types. The trajectories were based on the first five waves of this study. For every child, a trajectory was determined within each externalizing behavior type. Within the behavior types, the best possible number of groups with different developmental trajectories was estimated and selected using the Bayesian information criterion [20]. We used a Zero-Inflated Poisson (ZIP) distribution for estimating the trajectories. Estimation using a ZIP distribution addresses both non-normality and the abundance of zeros typically found in distributions of externalizing behavior [20, 21]. The largest probability for each individual indicated the trajectory that best matched to that individual’s behavior over time. With these probabilities, each child was assigned to the trajectory of each externalizing type that best described their individual developmental trajectory. Therefore, each child could be classified at the same time in, for example, a high-level trajectory for opposition and a low-level trajectory for aggression. There were equal amounts of younger and older children classified in each trajectory, since there were no age effects in the assignment of the individuals to the trajectories. The child’s trajectory group classifications were used in further analyses.

Fig. 2.

Developmental trajectories in childhood antisocial behavior types. Group-based developmental trajectories of aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations. The y axis represents the raw syndrome scores. (From Bongers et al. [21]; reprinted with permission of Blackwell Publishing.) Ado adolescence

Three trajectories were found for the externalizing behavior type aggression: a ‘near zero’ trajectory, a ‘low decreasers’ trajectory, and a ‘high decreasers’ trajectory. Six trajectories were found for the behavior type opposition: a ‘near zero’ trajectory, a ‘low decreasers’ trajectory, a ‘medium decreasers’ trajectory, an ‘adolescent increasers’ trajectory, a ‘high persisters’ trajectory, and a ‘high decreasers’ trajectory. Four trajectories were found for property violations: a ‘near zero’ trajectory, a ‘low decreasers’ trajectory, a ‘high persisters’ trajectory, and an ‘extremely high persisters’ trajectory. Because the ‘extremely high persisters’ group of property violations consisted of only two participants, this group was combined with the ‘high persisters’ group. In status violations, a ‘near zero’ trajectory, an ‘adolescent decreasers’ trajectory, a ‘medium increasers’ trajectory, and a ‘high increasers’ trajectory was found. The number of individuals within each trajectory can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of participants in the developmental trajectories

| Developmental trajectory | N | Percentage of total sample | Percentage males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | |||

| Near zero | 1,473 | 71.0 | 41.7 |

| Medium decreasers | 444 | 21.4 | 65.3 |

| High decreasers | 159 | 7.7 | 70.4 |

| Opposition | |||

| Near zero | 148 | 7.1 | 43.9 |

| Low decreasers | 491 | 23.7 | 44.6 |

| Medium decreasers | 674 | 32.5 | 50.3 |

| Adolescence increasers | 125 | 6.0 | 41.6 |

| High decreasers | 503 | 24.2 | 53.5 |

| High persisters | 135 | 6.5 | 53.3 |

| Property violations | |||

| Near zero | 1,548 | 74.6 | 45.4 |

| Low decreasers | 421 | 20.3 | 56.3 |

| High persisters | 107 | 5.2 | 71.0 |

| Status violations | |||

| Near zero | 1,052 | 50.7 | 43.7 |

| Adolescence increasers | 485 | 23.4 | 46.8 |

| Medium increasers | 514 | 24.8 | 60.5 |

| High increasers | 25 | 1.2 | 72.0 |

Number of individuals within each trajectory, percentage of individuals within each trajectory of the total sample, and percentage of males within each trajectory of the total sample

The items of the CBCL can be scored on two general scales: internalizing behavior (i.e., anxiety and depression) and externalizing behavior (i.e., delinquent and aggressive behavior). In this study, we used internalizing and externalizing scores measured at time 1 in 1983.

To investigate selective attrition, all dropouts and participants were compared with respect to their 1983 scale scores, using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and adjusting for age and gender. No significant difference was found between participants with missing assessments and participants with assessments in all five waves, on any of the CBCL scales (see Bongers et al. [21] for further details about the analysis).

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

The computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; [30] and three sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) for DSM-IV diagnoses [31] were used to obtain diagnoses of mental disorder in the 12 months prior to the interview (past year diagnoses). The CIDI and DIS are fully structured interviews to allow administration by lay interviewers and scoring of DSM-IV [32] by computer. Good reliability and validity have been reported for the CIDI [33]. Because information concerning disruptive disorders in adulthood (oppositional defiant, antisocial personality disorder, and ADHD) was lacking in this version of the CIDI, sections of the DIS covering these disorders were administered. Because the cell sizes for specific disorders were small for the majority of diagnoses, we constructed the following groupings of DSM-IV categories: (1) anxiety disorders, consisting of generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobia, or any anxiety disorder; (2) mood disorders, consisting of major depressive episode, bipolar disorder, dysthymia, or any mood disorder; (3) substance abuse/dependence, consisting of alcohol abuse/dependence, drug abuse/dependence, or both; (4) disruptive disorders, consisting of oppositional defiant disorder, antisocial personality disorder, ADHD, attention deficit only, hyperactivity only, or any disruptive disorder; and (5) any disorder, consisting of any of the above disorders or other disorders such as bulimia nervosa, somatization, conversion, pain disorder, hypochondriasis, and brief psychotic disorder.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression analyses

To investigate associations between childhood externalizing developmental trajectories in childhood and psychopathology in adulthood, we performed multiple logistic regression analyses for each externalizing behavior type separately. We tested whether associations existed between the trajectories in the four externalizing behavior types and DSM-IV disorders at follow-up. The regression analyses included gender, age, and SES at follow-up as covariates. Because the associations between the trajectories of externalizing behavior and adult disorders might be confounded by associations with internalizing and externalizing behavior, we added two more covariates. We added internalizing and externalizing scores assessed with the CBCL at time 1 to the regression analyses to adjust for their effects on the associations. In this way, we determined whether the trajectories predicted adult psychiatric disorders over and above comorbid general internalizing and externalizing behavior. For all models, we first determined whether there were interaction effects of sex or age with the separate trajectories. No significant interaction effects were found. The ‘near zero’ trajectory of each type was used as reference group in each regression analysis.

Results

In the multiple regression analyses, many associations were found between childhood externalizing developmental trajectories and adult disorders (Table 3). All four externalizing types predicted later disruptive disorders. Besides disruptive disorders, the oppositional type was also associated with anxiety disorders in adulthood. The trajectories in the status violations type also predicted substance abuse/dependence, anxiety, and mood disorder. Primarily high-level trajectories in the types predicted problems, but also medium-level trajectories were highly predictive.

Table 3.

Associations between developmental trajectories of child externalizing problems and disorders in adulthood

| Predictors | N | DSM-IV disorders at follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any disorder N = 356 OR (95% CI) |

Disruptive disorder N = 121 OR (95% CI) |

Substance abuse/dependence N = 120 OR (95% CI) |

Anxiety disorder N = 183 OR (95% CI) |

Mood disorder N = 36 OR (95% CI) |

||

| Aggression | ||||||

| High decreasers | 82 | 2.4 (2.1–5.1) | ||||

| Low decreasers | 275 | |||||

| Near zero | 982 | |||||

| Sex (male) | 3.3 (2.1–5.1) | 2.9 (1.9–4.5) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.8) | ||

| SES | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | |||||

| General externalizing | ||||||

| General internalizing | ||||||

| Oppositional | ||||||

| High persisters | 73 | 3.1 (1.3–7.5) | 4.6 (1.2–17.7) | 3.1 (1.1–9.6) | ||

| High decreasers | 315 | 2.3 (1.2–4.3) | ||||

| Ado increasers | 89 | |||||

| Medium decreasers | 426 | |||||

| Low decreasers | 334 | |||||

| Near zero | 102 | |||||

| Sex (male) | 3.7 (2.4–5.7) | 3.0 (1.9–4.5) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | ||

| SES | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | |||||

| General externalizing | ||||||

| General internalizing | ||||||

| Property violations | ||||||

| High persisters | 55 | 2.3 (1.3–4.3) | 3.8 (1.8–8.2) | |||

| Low decreasers | 276 | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | |||

| Near zero | 1,008 | |||||

| Sex (male) | 3.3 (2.2–5.1) | 2.8 (1.9–4.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | ||

| SES | ||||||

| General externalizing | ||||||

| General internalizing | ||||||

| Status violations | ||||||

| High increasers | 15 | 3.8 (1.3–11.1) | 11.7 (3.4–40.2) | 7.1 (1.1–47.1) | ||

| Medium increasers | 309 | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 1.7 (1.1–2.8) | 2.3 (1.4–3.8) | 1.6 (1.1–2.5) | |

| Ado increasers | 320 | 2.8 (1.1–7.1) | ||||

| Near zero | 695 | |||||

| Sex (male) | 3.3 (2.2–5.1) | 2.7 (1.8–4.2) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | ||

| SES | ||||||

| General externalizing | ||||||

| General internalizing | ||||||

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) are derived from multiple logistic regression analysis. Near zero groups were reference groups in the regression analyses. Only significant results are presented

Ado adolescence

Discussion

This study examined the relations between childhood trajectories of four distinctive types of externalizing behavior and DSM-IV disorders in adulthood in a longitudinal general-population sample that included males and females aged 4–16 years assessed at six time periods. All four types of externalizing behavior (i.e., aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations) in childhood, showed associations with disruptive behavior in adulthood. Children displaying externalizing behavior of the oppositional type (e.g., arguing, disobedience, temper tantrums) also showed anxiety disorder in adulthood. Children in trajectories of the status violation type (e.g., runaway, truancy, drug, and alcohol use) showed primarily substance use, anxiety, and mood disorder in adulthood. Furthermore, we found that children who are in high-level externalizing behavior trajectories are most at risk to suffer from disorders in adulthood, that is, both internalizing and externalizing disorders. This 24-year follow-up study is unique in prospectively examining the adult outcomes of different developmental trajectories in four childhood types of externalizing behavior, in a large general-population sample of 1,399 children.

Consistent with results of previous longitudinal studies in the general population that investigated the long-term continuity of early externalizing behavior [5, 14, 34], we can conclude that children with externalizing behavior are at increased risk for adverse outcomes in adulthood. Moreover, even after 24 years, children in all subtypes of externalizing behavior are at increased risk to suffer from internalizing and externalizing adult disorders. In addition, our study emphasizes the need to distinguish between the subtypes of externalizing behavior because we found differences between the predictive values of the different types of externalizing behavior. Of the four types of externalizing behavior, aggression (mainly including physical aggression) showed the least associations with adult psychopathology, whereas opposition and property violations mainly predicted adult disruptive disorder.

The status violations subtype was the weakest predictor for later disruptive behavior. However, children with behavior problems of this type showed substance use, anxiety, and mood disorder in adulthood. In a study that investigated which subtypes of externalizing behavior accounted for substance use [16], it was also found that status violations predicts substance use in late adolescence. In our study, we found that even up to middle adulthood, strong associations were found between status violations and substance use. Studies that investigated the comorbidity between alcohol, drugs, and internalizing disorders reported that ‘self medication’ with alcohol or drugs was associated with an increased likelihood of anxiety disorders [35, 36]. This verifies our finding of anxiety and substance use disorder in adulthood being related to status violations. Furthermore, another possible explanation for our finding of associations between childhood externalizing behavior types and adult internalizing disorders could be that the status violations and oppositional type comprise behaviors that are more reactive, nondestructive, and affective behaviors, and entail negative emotionality (e.g., anger, runaway, rule breaking), in contrast to aggression and property violations types that primarily comprise proactive and violent behaviors that are offensive and instrumental (e.g., bullying, vandalism). Proactive and reactive aggressions are two distinct subtypes of externalizing behavior and they have been found to differ in adult outcome. Proactive individuals tend to bully and be very unemotional, whereas reactive individuals show impulsive, angry responses to aversive events, particularly perceived by interpersonal threat [24, 25]. In accordance with previous findings on reactive and proactive aggressive behavior, we found that children with more reactive, nondestructive externalizing problems (i.e., status violations and oppositional) suffer from later internalizing problems [25, 37].

Because externalizing behaviors are expected to change largely in level and growth during childhood and adolescence [5, 38], and are therefore best described from a developmental point of view [39], we explored outcomes of trajectories of behavior in the current study, taking into account the developmental change through childhood and adolescence. We used LCGA to analyze trajectories of externalizing behavior, because this method is well adapted for modeling growth of phenomena within a population in which population members are not following a common developmental process of growth or decline. Consequently, we were able to report unique associations between distinctive developmental trajectories within every externalizing behavior type and adult internalizing and externalizing outcomes.

In accordance with findings of previous studies that investigated development of externalizing behavior, we found that children in high-level externalizing trajectories are most likely to suffer from adult problems [5, 8, 11, 15, 22, 23]. Children in the most severe, high-level trajectory of opposition and property violations were almost four to five times more likely than children not displaying these problems to suffer from any disruptive behavior in adulthood. Findings of a study that investigated continuity of externalizing behavior up to the age of 32 show that externalizing individuals in a severe ‘life-course-persistent’ trajectory suffered from the most mental health problems [5]. In a review of conduct disorder and its outcomes in general population studies it was found that increasing severity of externalizing behavior was associated with an increasing risk of an emotional disorder in adulthood [11]. What this study adds to the literature is that we extend the above findings by confirming that high levels of externalizing behavior in childhood and adolescence are linked to poor outcomes in adulthood even up to age 40.

However, it should be noted that children in both low- and high-level trajectories of property violations showed persistence of externalizing behavior into adulthood in terms of having disruptive behavior in adulthood. This shows that children displaying behavior of the property violations type are at risk to suffer from adult problems, even if they develop through a low-level and decreasing trajectory during childhood and adolescence. Property violations comprise behaviors such as cruel to animals, fire setting, and vandalism. These behaviors are symptoms of both psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder [32, 40], which are both very serious diagnoses. Possibly, the separate symptoms in this property violations type are that severe and radical, that even children who show relatively few of the symptoms comprising this property violations type, thus who develop through a low-level in this type, suffer from disruptive disorder in adulthood.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of two limitations. First, although we achieved a relatively high response rate in a 24-year follow-up, a considerable proportion of the original sample from 1983 did not participate in this follow-up. By interpreting our results, one should be aware of the fact that in longitudinal population based studies, high-risk people are the most difficult to keep included. Although selective attrition effects were small in this study, some children with the most severe externalizing behavior problems were not included. Therefore, results may not generalize to high-risk populations. Consequently, studies on high-risk children are essential to complete the present findings on the predictive value of developmental trajectories of externalizing behavior. Second, the results of this study may have been influenced by time dependent environmental covariates, such as economic growth, ethnic distributions, or family structures that we did not control for.

Conclusions

Our study shows a relation between child to adolescent externalizing behavior and adult psychopathology, even over a 24 years time-interval. We can conclude that an elevated level of externalizing behavior in childhood has impact on the long-term outcome, regardless of the developmental course of externalizing behavior. Therefore, intervention and prevention should focus on individuals that show severe externalizing problems at any point in childhood or adolescence. Furthermore, we can conclude that different types of externalizing behavior (i.e., aggression, opposition, property violations, and status violations) are related to different adult outcomes, and it is therefore advisable to treat them separately. Mental health professionals working with children and adolescents with externalizing behavior should anticipate different developmental trajectories through life. Because children and adolescents with externalizing behavior of the status violations subtype were most likely to be affected in adulthood, we recommend that prevention and intervention should focus on children and adolescents showing behavior of this type such as substance abuse, truancy, and runaway.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Dishion TJ, French D, Patterson GR. The development and ecology of antisocial behavior. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Manual of developmental psychopathology. New York: John Whiley; 1995. pp. 421–471. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, Fergusson D, Horwood JL, Loeber R, Laird R, Lynam DR, Moffitt TE, Pettit GS, Vitaro F. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: a six-site, cross-national study. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:222–245. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Copeland WE, Miller-Johnson S, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1668–1675. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Moulton JL., 3rd Lifetime criminality among boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a prospective follow-up study into adulthood using official arrest records. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: from childhood origins to adult outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshaw J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M, Silberg J, O’Connor T, Meyer J, Maes H. Predictors of antisocial personality: continuities from childhood to adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:118–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sourander A, Pihlakoski L, Aromaa M, Rautava P, Helenius H, Sillanpää M. Early predictors of parent- and self-reported perceived global psychological difficulties among adolescents: a prospective cohort study from age 3 to age 15. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:173–182. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ. Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sourander A, Jensen P, Davies M, Niemela S, Elonheimo H, Ristkari T, Helenius H, Sillanmaki L, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Almqvist F. Who is at greatest risk of adverse long-term outcomes? The Finnish from a boy to a man study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1148–1161. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31809861e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoccolillo M. Cooccurrence of conduct disorder and its adult outcomes with depressive and anxiety disorders—a review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:547–556. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199205000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse and dependence: results of a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(Suppl 1):S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick PJ, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Tannenbaum L, Van Horn Y, Christ MAG, Hart EL, Hanson K. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a meta-analytic review of factor analyses and cross-validation in a clinic sample. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13:319–340. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(93)90016-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:837–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Predicting young adult social functioning from developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviour. Psychol Med. 2008;38:989–999. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmermans M, van Lier PA, Koot HM. Which forms of child/adolescent externalizing behaviors account for late adolescent risky sexual behavior and substance use? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung IJ, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Gilchrist LD, Nagin DS. Childhood predictors of offense trajectories. J Res Crime Delinq. 2002;39:60–90. doi: 10.1177/002242780203900103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White HR, Bates ME, Buyske S. Adolescence-limited versus persistent delinquency: extending Moffitt’s hypothesis into adulthood. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:600–609. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiesner M, Kim HK, Capaldi DM. Developmental trajectories of offending: validation and prediction to young adult alcohol use, drug use, and depressive symptoms. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17:251–270. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2004;75:1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odgers CL, Caspi A, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Poulton R, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Moffitt TE. Prediction of differential adult health burden by conduct problem subtypes in males. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:476–484. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoccolillo M, Pickles A, Quinton D, Rutter M. The outcome of childhood conduct disorder: implications for defining adult personality disorder and conduct disorder. Psychol Med. 1992;22:971–986. doi: 10.1017/S003329170003854X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodge KA, Coie JD. Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:1146–1158. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay R. Reactively and proactively aggressive children: antecedent and subsequent characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:495–505. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Meurs I, Reef J, Verhulst F, van der Ende J. Intergenerational transmission of child problem behaviors: a longitudinal, population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;48:138–145. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318191770d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Westerlaak JH, Kropman JA, Collaris JWM. Beroepenklapper (manual for occupational level) Nijmegen: Instituut voor Sociologie; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Achenbach TM. Manual for the child behavior checklist/4-18 and 1991 child profile. Burlington, Vermont: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verhulst FC, van der Ende J, Koot HM (1996) Handleiding voor de CBCL/4-18 (Manual for the CBCL/4-18). Erasmus University/Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam

- 30.World Health Organization . Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS (1981) National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 38:381–389 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews G, Peters L. The psychometric properties of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:80–88. doi: 10.1007/s001270050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofstra MB, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Continuity and change of psychopathology from childhood into adulthood: a 14-year follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:850–858. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ (2010) Structural models of the comorbidity of internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in a longitudinal birth cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Robinson J, Sareen J, Cox BJ, Bolton J. Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: results from a nationally representative sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodge KA, Lochman JE, Harnish JD, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:37–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loeber R, Wung P, Keenan K, Giroux B, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Welmoet B, Van Kammen WB, Maughan B. Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5:103–133. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. Ratings of relations between DSM-IV diagnostic categories and items of the CBCL/6-18, TRF, and YSR. Burlington, Vermont: University of Vermont, Research Center For Children, Youth And Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hare RD, Hart SD, Harpur TJ. Psychopathy and the DSM-IV criteria for antisocial personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:391–398. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]