Abstract

In response to environmental stress, cells induce a program of gene expression designed to remedy cellular damage or, alternatively, induce apoptosis. In this report, we explore the role of a family of protein kinases that phosphorylate eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) in coordinating stress gene responses. We find that expression of activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a member of the ATF/CREB subfamily of basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) proteins, is induced in response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress or amino acid starvation by a mechanism requiring eIF2 kinases PEK (Perk or EIF2AK3) and GCN2 (EIF2AK4), respectively. Increased expression of ATF3 protein occurs early in response to stress by a mechanism requiring the related bZIP transcriptional regulator ATF4. ATF3 contributes to induction of the CHOP transcriptional factor in response to amino acid starvation, and loss of ATF3 function significantly lowers stress-induced expression of GADD34, an eIF2 protein phosphatase regulatory subunit implicated in feedback control of the eIF2 kinase stress response. Overexpression of ATF3 in mouse embryo fibroblasts partially bypasses the requirement for PEK for induction of GADD34 in response to ER stress, further supporting the idea that ATF3 functions directly or indirectly as a transcriptional activator of genes targeted by the eIF2 kinase stress pathway. These results indicate that ATF3 has an integral role in the coordinate gene expression induced by eIF2 kinases. Given that ATF3 is induced by a very large number of environmental insults, this study supports involvement of eIF2 kinases in the coordination of gene expression in response to a more diverse set of stress conditions than previously proposed.

Environmental stresses induce a program of coordinate gene expression designed to remedy the underlying cellular disturbance or, alternatively, induce apoptosis. Facilitating this stress response are transcriptional regulators, such as activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), a member of the ATF/CREB subfamily of the basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) family (26). ATF3 levels are dramatically induced in response to a variety of stress conditions in many different tissues (26, 27). For example, ATF3 is increased in liver exposed to acetaminophen, cycloheximide, carbon tetrachloride, or alcohol, in heart or pancreas subjected to ischemia coupled with reperfusion, in brain by seizure, in pancreas following streptozotocin treatment, and in cultured cells following exposure to a variety of stress treatments, including UV light and ionizing radiation, proteasome inhibitors, and homocysteine. ATF3 mRNA usually increases within 2 h of stress exposure, and ATF3 protein can function as a homodimer or as a complex with members of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) family of transcription factors, such as the apoptosis-inducing protein CHOP (also designated GADD153) that is linked to diabetes (13, 22, 24, 26, 27, 50). The molecular basis for the stress induction of ATF3 and the scope of its target genes are not well understood.

We have been interested in the early events of stress responses involving a family of protein kinases that phosphorylate the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2). eIF2 combined with GTP delivers initiator Met-tRNA to the 40S ribosome (35). After association of the preinitiation complex to mRNA and ribosomal recognition of the initiation codon, the GTP associated with eIF2 is hydrolyzed to GDP and eIF2 is released from the ribosome. Recycling of eIF2 to the active GTP-bound form requires a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, eIF2B, and phosphorylation of eIF2α alters this initiation factor from a substrate to an inhibitor of the eIF2B exchange factor. The resulting reduction in eIF2-GTP levels has been shown to impact both general and gene-specific translation (15, 36, 67).

Four distinct eIF2 kinases have been identified in mammals, and each contains unique regulatory domains important for detection of different stress conditions and kinase activation (14, 32, 36, 54, 58, 67). For example, impaired assembly of proteins targeted for the secretory pathway leads to enhanced phosphorylation of eIF2α by pancreatic eIF2 kinase (PEK, also designated pancreatic endoplasmic reticulum [ER] kinase, Perk, or EIF2AK3). Recognition of this so-called ER stress by the ER transmembrane protein PEK is proposed to occur through interaction with ER chaperones, such as GRP78/BiP, with a portion of the ER lumenal sequences of PEK (5, 43, 54). Accumulation of misfolded protein during stress is thought to titrate off the repressing ER chaperone from its association with PEK, allowing for oligomerization between PEK polypeptides that is required for induction of its eIF2 kinase activity. In the cytoplasm, the eIF2 kinase GCN2 detects amino acid limitation through the consequent elevated levels of uncharged tRNA (19, 23, 30, 36, 62, 67, 68, 76, 77). Such uncharged tRNA interacts with a regulatory domain of GCN2 homologous to histidyl-tRNA synthetase enzymes, leading to a proposed release of an inhibitory interaction between the carboxy-terminal sequences of GCN2 and its catalytic domain. GCN2 association with uncharged tRNA is not limited to histidyl-tRNA, and thus, this eIF2 kinase can recognize a broad range of amino acid limitations. Impaired recognition of stress conditions by eIF2 kinases, and the resulting loss of the appropriate gene expression pathways, can have severe medical consequences. In the case of PEK (EIF2AK3 gene) in humans, loss of this eIF2 kinase function leads to a rare autosomal recessive disorder, Wolcott-Rallison syndrome (WRS) (17). WRS is characterized by neonatal insulin-dependent diabetes accompanied by a characteristic loss of the pancreatic beta cells and an occurrence of epiphyseal dysplasia, osteoporosis, and growth retardation (12, 64). PEK−/− (Perk−/−) mice display similar pancreatic and bone defects and succumb to complications related to severe hyperglycemia within several weeks of birth (28, 75).

While the linkage between individual eIF2 kinases and certain stress conditions is well established, we are only beginning to appreciate the details of the gene expression changes directed by eIF2α phosphorylation. In the well-characterized yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, phosphorylation of eIF2α by GCN2 protein kinase leads to preferential translation of GCN4 by a mechanism involving four short open reading frames in the 5′-noncoding portion of the GCN4 mRNA (1, 36). GCN4 is a bZIP transcriptional activator of a large number of genes involved in the metabolism of amino acids, nucleotides, and vitamins and biogenesis of peroxisomes (37, 46). While no GCN4 orthologue exists in mammals, another bZIP activator, ATF4, is translationally induced in response to eIF2α phosphorylation by a mechanism involving upstream open reading frames (30). However, a recent DNA microarray study indicated that less than a third of the genes requiring PEK for activation in response to ER stress were affected by loss of ATF4 function (33). This suggests that additional transcriptional regulators are critical participants in the eIF2 kinase stress responses. Phosphorylation of eIF2α during ER stress in higher eukaryotes also functions in concert with the unfolded protein response (UPR) (29, 41, 52). The UPR involves the expression of a large number of genes important for facilitating protein secretion, such as the well-characterized ER chaperone gene GRP78.

In this study, we used mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) carrying deletions of eIF2 kinase genes, ATF3, or ATF4 to address the role of ATF3 in stress responses mediated by eIF2 kinases. Induction of ATF3 requires PEK during ER stress and GCN2 in response to amino acid starvation. Elevated levels of ATF3 are important for expression of CHOP in response to leucine starvation, but not ER stress, and for full induction of the eIF2 protein phosphatase targeting subunit, GADD34, in response to either stress condition. We conclude that ATF3 has a primary role in the eIF2 kinase stress response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfections, and stress conditions.

MEF cells were isolated by trypsinization of embryos dissected from day 12 to day 14 of gestation from crosses between heterozygous PEK+/− (Perk+/−) animals (75) or between GCN2−/− (76) or ATF3−/− mice (M. G. Hartman, M.-L. Kim, D. Lu, G. L. Kociba, T. Shukri, J. Buteau, X. Wang, W. L. Frankel, D. Guttridge, M. Prentki, S. Grey, D. Ron, and T. Hai, submitted for publication) mice as previously described (71). MEF cells were previously reported from PKR−/− (73) and ATF4−/− (33) mice. Genotyping of these cell lines was established by PCR analysis as previously described, and deletions were confirmed by immunoblot measurements of the PEK, GCN2, PKR, ATF3, and ATF4 proteins (33, 73, 75, 76; Hartman et al., submitted). MEF cells were also isolated from embryos obtained from crosses between PEK+/− GCN2−/− mice and between PEK+/− GCN2−/− PKR−/− animals, and genotyping was carried out by PCR analysis. PEK and GCN2 deletions remove regions encoding essential portions of the eIF2 kinase domains and lead to no detectable protein, as judged by immunoblotting (75, 76). PKR−/− cells express low levels of a truncated PKR product that is missing amino-terminal regulatory sequences required for eIF2 kinase function in vivo (4, 65, 66, 73). MEF cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; BioWhittaker) supplemented with 1 mM nonessential amino acids, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml and immortalized by infection with a recombinant retrovirus expressing simian virus 40 large T antigen (70).

ER stress in MEF cells was brought about by addition of 1 μM thapsigargin to the medium and incubation for the indicated times. MEF cells were subjected to amino acid starvation by culturing in DMEM without leucine (BioWhittaker). Patterns of eIF2α phosphorylation induced in response to nutrient or ER stress were similar between the primary MEFs and immortalized MEF cell lines. To address the role of protein synthesis or transcription in bZIP protein expression during ER stress, 50 μg of cycloheximide per ml or 10 μg of actinomycin D per ml was added to PEK+/+ cells along with 1 μM thapsigargin and the cells were incubated for 3 or 6 h prior to collection and analysis. MEF, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T, and NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with expression plasmids by using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen Life Technologies). After the transfected cells had been cultured for 48 h, they were treated with 1 μM thapsigargin for 6 h. The PEK cDNA was inserted downstream of the cytomegalovirus promoter in plasmid pcDNA3, and ATF3 was expressed by using the pCGF vector.

Preparation of protein lysates and immunoblot analyses.

MEF cells subjected to the indicated stress or no stress were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline solution. Cell lysates were prepared by using lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 100 mM NaF, 17.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors (100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.15 μM aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin), sonicated for 30 s, and clarified by centrifugation. Supernatants were analyzed for protein content by the Bio-Rad protein quantitation kit for detergent lysis in accordance with the manufacturer's directions. For immunoblot assays, the same amount of each protein sample was separated in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. Low- and high-range polypeptide markers (Bio-Rad) were used to measure the molecular weights of proteins. Immunoblot analyses were carried out with a TBS-T solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20 supplemented with 4% nonfat milk. Filters were incubated with an antibody that specifically recognizes the indicated protein. ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, and GRP78/BiP antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, actin monoclonal antibody was obtained from Sigma, and PEK antibody was prepared as previously described (61). ATF3 and ATF4 studies were independently confirmed with ATF4 and ATF3 polyclonal antibodies that were prepared from recombinant proteins. Immunoblot assays measuring eIF2α phosphorylation were performed with a polyclonal antibody that specifically recognizes phosphorylated eIF2α at Ser-51 (Research Genetics or StressGen). A monoclonal antibody that recognizes either phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated forms of eIF2α was provided by Scot Kimball (College of Medicine, Pennsylvania State University, Hershey). Following incubation of the antibody with the filters, the blots were washed three times in TBS-T and incubated with TBS-T containing a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad). Filters were washed three times in TBS-T solution, and the antibody complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. The protein-antibody complexes were visualized with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody and a chemiluminescent substrate. To establish linearity in the immunoblot assays, proteins were serially diluted in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and multiple autoradiographic exposures were performed. Quantitation of visualized bands was carried out by densitometry.

RNA isolation and analyses.

Northern analyses were carried out as previously described (56). Total cellular RNA was isolated from MEFs treated with 1 μM thapsigargin for the indicated number of hours or no stress with the TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. A 20-μg portion of RNA from each sample preparation was separated by electrophoresis with a 1.4% agarose-6% formaldehyde gel and visualized by using ethidium bromide staining and UV light. RNA was transferred onto GeneScreen Plus filters (New England Nuclear) and hybridized to 32P-labeled DNA probes, and filters were washed under high-stringency conditions and visualized by autoradiography. The probe for CHOP included a 540-bp DNA fragment from the coding region that was kindly provided by Ma Yanjun, St. Jude's Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn. The probe for ATF3 was a 646-bp DNA segment generated by PCR that included the coding region of this transcription factor.

EMSA.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from cells as described previously (39). Briefly, cells were resuspended in 1 ml of cold hypotonic RSB buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 0.5% NP-40 and protease inhibitors. Following a 15-min incubation on ice, the cells were lysed with a Dounce homogenizer. Nuclei were resuspended in 2 packed nuclear volumes of extraction buffer C (420 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors and incubated on ice for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay. The core sequences of the double-stranded oligonucleotides used in the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) include a previously published ATF-C/EBP composite binding sequence (CATTGCATCATC) (22), NFκB binding sequence (GGGTTTTCC) (39), or ATF/CREB binding element (GTGACGTCAG) beginning at position −77 in the mouse GADD34 promoter (38). The sequence of the double-stranded oligonucleotide for octomer 1 (OCT1) binding was TGTCGAATGCAAATCACTAGAA (39). For the binding reaction, 32P-labeled DNA fragments (20,000 to 25,000 cpm), 5 μg of nuclear extract, and 2.5 μg of poly(dI-dC), as a nonspecific competitor, were added to a solution containing 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 4 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 100 mM KCl, and 2.5% glycerol in a final assay volume of 25 μl. The binding assay was carried out at room temperature for 30 min, and DNA-protein complexes were separated by gel electrophoresis as previously described (63). Where indicated, excess unlabeled competitor DNA fragments were added to the assay mixture to ascertain binding specificity.

RESULTS

PEK is required for coordinate induction of ATF3, as well as ATF4 and CHOP.

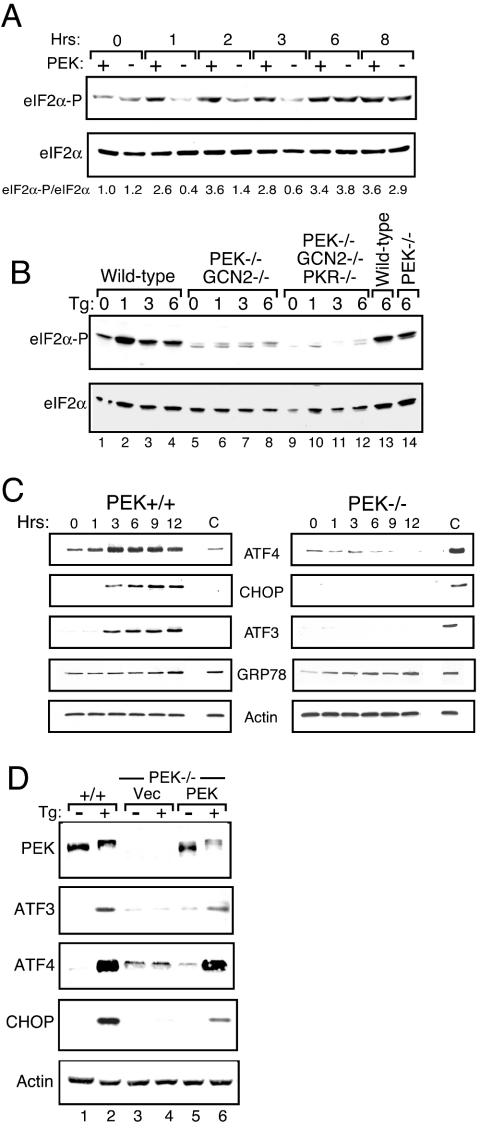

Phosphorylation of eIF2α by PEK is an early event in a coordinate gene expression response to ER stress (31, 32, 43, 61). PEK+/+ and PEK−/− MEF cells were treated with thapsigargin, a known ER stress agent that triggers release of calcium from this organelle, and levels of phosphorylation of the α subunit of eIF2 at Ser-51 were measured by immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies specific to this phosphorylated epitope (Fig. 1A). Within 1 h of thapsigargin treatment, eIF2α phosphorylation was significantly increased in cells with functional PEK, and these elevated levels were sustained after 8 h of exposure. By comparison, minimal phosphorylation of eIF2α was observed in PEK−/− cells subjected to ER stress for up to 3 h. However, following 6 h of thapsigargin treatment, the levels of eIF2α phosphorylation were increased in the absence of PEK activity, with elevated eIF2α phosphorylation in the PEK+/+ and PEK−/− cells subjected to 8 h of ER stress. These results indicate that PEK is the primary activated eIF2 kinase during ER stress, with the activity of one or more secondary eIF2 kinases being induced with extended stress of the ER organelle.

FIG. 1.

Enhanced expression of ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP in response to ER stress requires PEK activity. PEK+/+ and PEK−/− MEF cells were exposed to the presence of thapsigargin (Tg) for the indicated number of hours or to the absence of this ER stress agent (0 h). (A) Whole-cell lysates were prepared from the cultured cells, and the levels of eIF2α specifically phosphorylated at Ser-51 (eIF2α-P) or total eIF2α were measured by immunoblot analysis. The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane. Relative levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were normalized to levels of total eIF2α in each lysate preparation. (B) MEF cells containing functional eIF2 kinases (wildtype, lanes 1 to 4 and 13; PEK−/− GCN2−/−, lanes 5 to 8; PEK−/− GCN2−/− PKR−/−, lanes 9 to 12; PEK−/−, lane 14) were treated with thapsigargin for the indicated number of hours. Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were measured by immunoblot assay. (C) Levels of ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, GRP78, and actin were measured by immunoblot analysis with an antibody specific to each protein. To facilitate normalization between PEK+/+ and PEK−/− panels, the lysate from PEK−/− cells that were stressed for 6 h was included in lane C of the PEK+/+ panel. Similarly, lane C in the PEK−/− immunoblot panel was an analysis of lysate prepared from PEK+/+ MEF cells treated with thapsigargin for 6 h. (D) A plasmid expressing PEK was transiently transfected into PEK−/− MEF cells (lanes 5 and 6), and PEK+/+ and transfected cells were subjected to the presence (+) or absence (−) of ER stress for 6 h. Vec indicates that the parent expression plasmid alone was introduced into the PEK−/− MEF cells (lanes 3 and 4). Whole-cell lysates were prepared from these transfected cells, and ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, PEK, and actin were measured by immunoblot analysis.

In addition to PEK and GCN2, fibroblast cells express the eIF2 kinase PKR, which is important for translational control in response to viral infection (69). The fourth eIF2 kinase in mammals, HRI, is expressed predominantly in erythroid tissues and functions to couple heme availability to the synthesis of proteins, principally globin in this cell type (14). To address which eIF2 kinase is activated in response to extended ER stress conditions, combined PEK−/− GCN2−/− MEF cells or MEF cells carrying deletions of the eIF2 kinase genes PEK, GCN2, and PKR were subjected to ER stress. While phosphorylation of eIF2α was induced in the PEK−/− cells after 6 h of thapsigargin treatment, the combined PEK−/− GCN2−/− MEF cells showed minimal levels of eIF2α phosphorylation that was further reduced in cells carrying deletions of the three eIF2 kinase genes (Fig. 1A and B). These results indicate that PEK is the primary eIF2 kinase induced by ER stress, and GCN2 can function as a secondary kinase that is activated under an extended ER stress condition.

Expression of transcriptional activators ATF4 and CHOP was reported to be induced in response to eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress (30). ATF4 levels were increased in PEK+/+ cells after 1 h of thapsigargin treatment, with maximal expression after 3 h of ER stress (Fig. 1C). By comparison, in the absence of PEK activity, minimal amounts of ATF4 protein were detected even after 12 h of thapsigargin exposure. Levels of the control protein actin were unchanged during this ER stress. eIF2α phosphorylation was significantly induced in PEK−/− cells following 6 h of this ER stress; therefore, eIF2α phosphorylation alone does not appear to be sufficient for induction of ATF4 synthesis. Transcription of CHOP has been linked to ATF4 and eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress (22, 30, 44). Cells containing PEK activity induced CHOP mRNA and protein levels within 3 h of thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 1C and 2). By contrast, minimal CHOP mRNA and protein were detected in the absence of PEK activity.

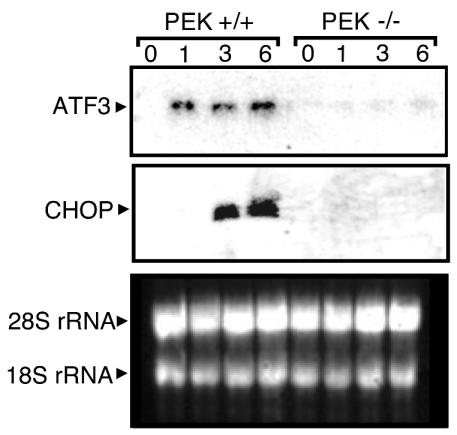

FIG. 2.

PEK facilitates increased expression of ATF3 and CHOP mRNAs during ER stress. PEK+/+ and PEK−/− MEF cells were treated in the presence or absence of ER stress for the indicated times, and the levels of ATF3 and CHOP transcripts were measured by Northern blot analysis with a probe specific to each gene. In the northern analysis (bottom panel), total RNA was subjected to gel electrophoresis and 18S and 28S rRNAs were visualized by ethidium bromide staining, showing that similar amounts of RNA was characterized between lanes.

ATF3 is expressed in response to a broad spectrum of stress conditions. We therefore measured ATF3 protein expression in PEK+/+ and PEK−/− cells in response to ER stress. Levels of ATF3 protein were significantly elevated between 1 and 3 h of thapsigargin treatment of MEF cells containing functional PEK, with only modest increases thereafter (Fig. 1C). Consistent with this protein induction, ATF3 mRNA levels in PEK+/+ cells were significantly enhanced within 1 h of ER stress, with continued high levels of this transcript after 6 h of thapsigargin exposure (Fig. 2). In the absence of PEK activity, no ATF3 protein or transcript was detected (Fig. 1C and 2). Transient transfection of a PEK cDNA into PEK−/− cells restored this stress response as judged by induced ATF3 protein, as well as ATF4 and CHOP expression upon thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, there was an accompanying activation of PEK involving autophosphorylation, as judged by a migration shift of this eIF2 kinase by immunoblotting. This migration shift is alleviated after phosphatase treatment or is absent with a similar transfection of a kinase-deficient PEK (32, 43). We concluded that PEK is required for the coordinate induction of ATF3, as well as ATF4 and CHOP, in response to ER stress. Further supporting this conclusion, we found that ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP were localized in the nuclei of ER-stressed PEK+/+ MEF cells, as judged by confocal microscopy with antibodies directed specifically against these transcription factors and a secondary antibody conjugated to rhodamine red (data not shown). Minimal immunofluorescence was detected in PEK+/+ cells in the absence of stress or in PEK−/− cells in the presence or absence of ER stress.

To further address whether PEK is essential for the UPR, we characterized the expression of GRP78, which has served as a model for UPR gene expression. GRP78 was induced in PEK+/+ cells in response to ER stress, with a gradual increase in protein levels following 3 h of thapsigargin exposure and a maximum after 12 h of stress (Fig. 1C). Elevated GRP78 protein levels were also observed in cells carrying a deletion of PEK (Fig. 1C), indicating that expression of at least a portion of the UPR-regulated genes can be induced independently of eIF2α phosphorylation.

Synthesis of mRNA and protein is required for induction of ATF3 and CHOP in response to ER stress.

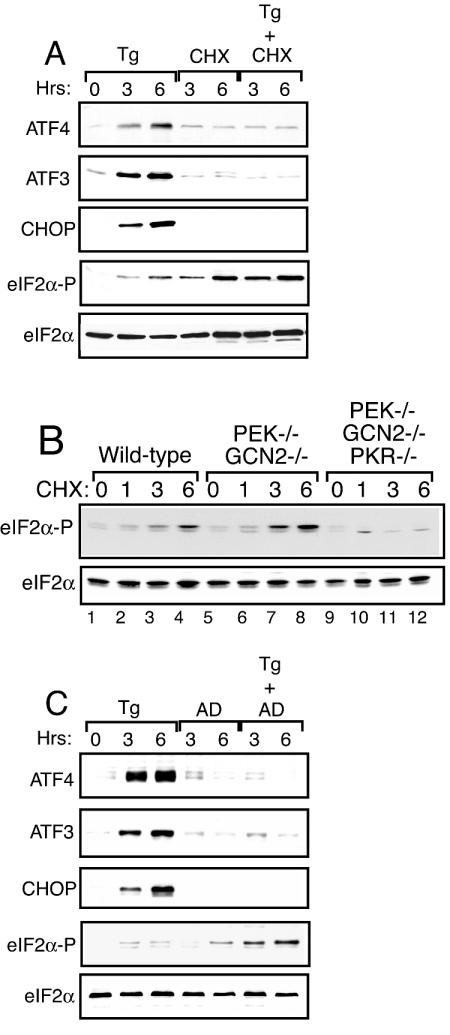

Although ATF4, ATF3, and CHOP are coordinately expressed in response to ER stress, there are differences between these genes regarding the contribution of transcriptional control and the timing of induced expression. Expression of ATF4 is translationally induced by eIF2α phosphorylation, with an additional role for mRNA synthesis in response to amino acid limitation, and possibly ER stress (30, 60). In the case of ATF3 and CHOP, increased mRNA levels were linked to their elevated protein expression in response to ER stress, and these increased transcript levels were absent in PEK−/− cells (Fig. 2). To formally address the role of protein and mRNA synthesis in the accumulation of these transcription factors, we measured their expression in ER-stressed PEK+/+ MEF cells treated in the presence or absence of cycloheximide or actinomycin D. Consistent with the idea that the ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP proteins are synthesized in response to ER stress, each of the transcription factors was significantly reduced by the addition of cycloheximide (Fig. 3A). As previously reported, addition of only cycloheximide increased the phosphorylation of eIF2α (40) and combined addition of thapsigargin and cycloheximide induced eIF2α phosphorylation to levels exceeding that measured in cells incubated with either agent alone (Fig. 3A). Τhis induced eIF2α phosphorylation by cycloheximide treatment was also observed in PEK−/− cells, indicating that this stress regulates the activity of alternative members of the eIF2 kinase family or eIF2α protein phosphatases (40). To determine the contribution of these alternative eIF2 kinases, we treated MEF cells carrying a deletion of GCN2 or PKR with cycloheximide and found levels of eIF2 phosphorylation similar to that measured for wild-type cells (data not shown). Furthermore, eIF2α phosphorylation was enhanced in combined GCN2−/− PEK−/− MEF cells following exposure to this translation inhibitor (Fig. 3B). Only MEF cells carrying deletions of eIF2 kinase genes PEK, GCN2, and PKR showed a significant reduction in eIF2α phosphorylation following cycloheximide exposure, suggesting that multiple eIF2 kinases contribute under this stress condition.

FIG. 3.

mRNA and protein synthesis are required for induced expression of ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP in response to ER stress. (A) PEK+/+ MEF cells were treated with thapsigargin (Tg) and/or cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated number of hours or not treated (0 h). (B) MEF cells containing functional eIF2 kinases (wild type, lanes 1 to 4; PEK−/− GCN2−/−, lanes 5 to 8; PEK−/− GCN2−/− PKR−/−, lanes 9 to 12) were treated with cycloheximide for the indicated number of hours. Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α were measured by immunoblot assay. (C) PEK+/+ MEF cells were treated with thapsigargin and/or actinomycin D (AD) for 3 or 6 h or not treated (0 h). Cell lysates were prepared from the cultured cells, and immunoblot analysis was used to measure the levels of ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P), and total eIF2α. The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane.

Addition of actinomycin D along with thapsigargin, followed by a 3- or 6-h incubation, resulted in no induction of ATF3 or CHOP protein (Fig. 3C), indicating that transcription during ER stress is required for elevated expression of these transcription factors. Minimal expression of ATF4 was detected in the presence of actinomycin D. Previously, it was reported that there was a significant reduction in ATF4 mRNA in ER-stressed cells after the addition of actinomycin D (30). This observation supports the idea that induction of ATF4 expression during stress involves increased mRNA synthesis, in addition to translational control. It is also noteworthy that actinomycin D treatment alone induced eIF2α phosphorylation, although we detected this after a 6-h exposure (Fig. 3C) (40). Combined addition of actinomycin D and thapsigargin increased phosphorylation of eIF2α to levels exceeding that measured in MEF cells incubated with either agent alone. Together, these results indicate that enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation occurs in response to agents that inhibit the general synthesis of mRNA or protein.

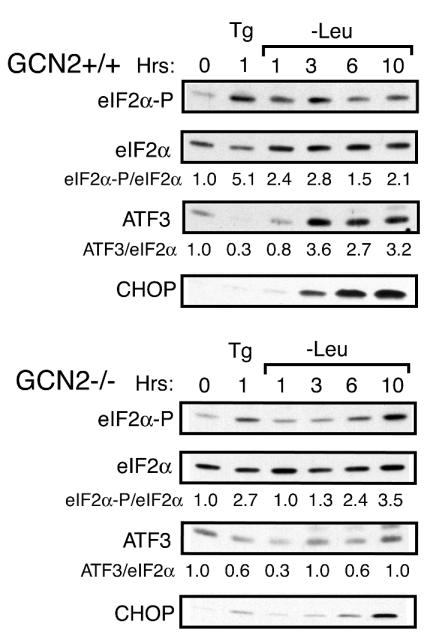

GCN2 facilitates induced expression of ATF3 and CHOP during nutrient stress.

We next asked whether the coordinate induction of ATF3 expression by eIF2α phosphorylation occurs in response to stresses other than those impacting the ER organelle. The cytoplasmic eIF2 kinase GCN2 is induced by amino acid limitation, and we grew GCN2+/+ and GCN2−/− MEF cells in nutrient-sufficient or leucine-depleted medium. Within 1 h of leucine depletion, there was a 2.4-fold increase in eIF2α phosphorylation in GCN2+/+ cells compared to nonstarved cells (Fig. 4). There were enhanced levels of ATF3 following 3 h of amino acid depletion that were maintained for up to 10 h of this nutrient stress (Fig. 4). Consistent with earlier observations, CHOP was also induced following 6 h of leucine starvation (7, 20, 30). By comparison, induction of eIF2α phosphorylation in GCN2−/− cells required a much longer nutrient stress, with phosphorylation detected only after 6 h of leucine deficiency. These results suggest that that one or more secondary eIF2 kinases in MEF cells can be activated in response to longer periods of amino acid limitation. In these GCN2−/− cells, there was in fact a modest decrease in ATF3 protein in response to leucine deprivation (Fig. 4). Similarly, significant levels of CHOP protein were only detected in the GCN2-deficient cells after 10 h of leucine starvation. GCN2 activity is not required for early phosphorylation of eIF2α in response to ER stress (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

ATF3 and CHOP are induced by eIF2 kinase GCN2 in response to amino acid depletion. GCN2+/+ and GCN2−/− MEF cells were grown in leucine-depleted medium for the indicated number of hours, exposed to thapsigargin (Tg), or subjected to no stress. Whole-cell lysates were prepared from the cultured cells, and the levels of phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P), total eIF2α, ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP were measured by immunoblot analysis. The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane. Relative levels of phosphorylated eIF2α or ATF3 under the indicated stress condition were normalized to levels of total eIF2α in each lysate preparation.

ATF3 is integral to the eIF2 kinase stress response.

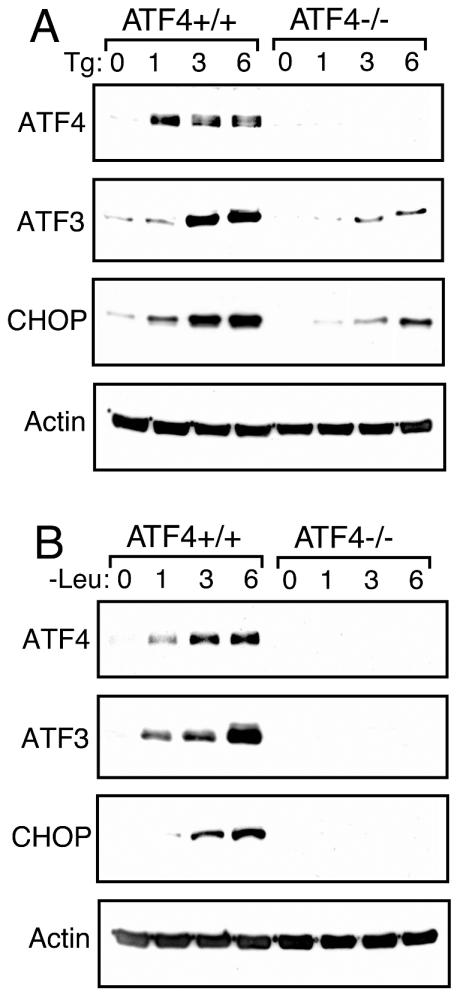

The sequential induction pattern of ATF4, ATF3, and CHOP suggests that these proteins may function in a cascade of transcriptional expression. For example, elevated levels of ATF4 may induce ATF3, which in turn may contribute to enhanced CHOP expression. To address this model, we measured ATF3 and CHOP protein levels in ATF4+/+ and ATF4−/− MEF cells subjected to ER stress or leucine starvation (Fig. 5A and B). While ATF4+/+ MEF cells showed a significant increase in ATF3 and CHOP levels in response to ER stress, the expression of both of these transcription factors was appreciably diminished in ATF4−/− cells (Fig. 5A). This requirement for ATF4 was also extended to amino acid deprivation whereby ATF3 and CHOP were not expressed in ATF4−/− cells (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Increased expression of ATF3 in response to ER or nutritional stress requires ATF4. ATF4+/+ and ATF4−/− MEF cells were treated with thapsigargin (Tg) (A), subjected to leucine starvation (B) for the indicated number of hours, or left untreated (0 h). The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane, and levels of ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, and actin were measured as indicated by immunoblot analysis with protein-specific antibodies.

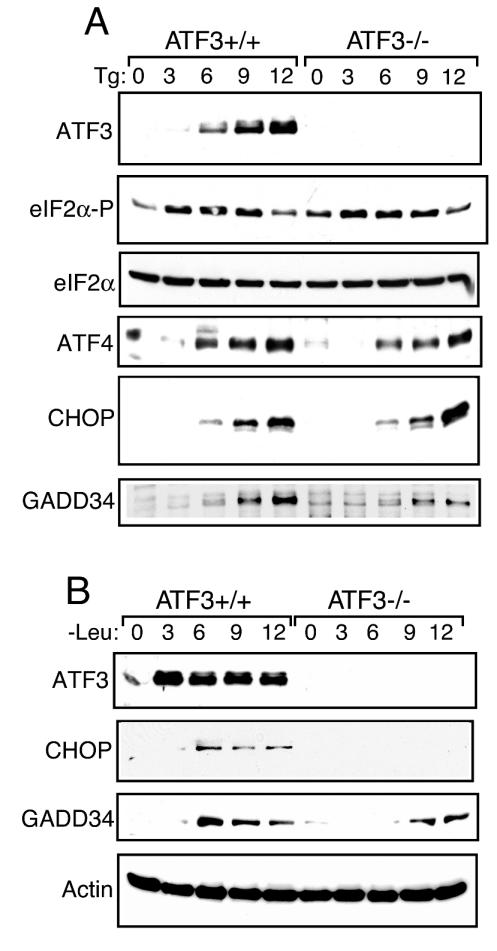

To determine whether ATF3 is important for induction of CHOP, we measured CHOP protein levels in ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− MEF cells subjected to ER stress or leucine starvation (Fig. 6A and B). Deletion of ATF3 did not appreciably affect induction of eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ER stress, although eIF2α phosphorylation in nonstressed ATF3−/− cells was slightly higher than in their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 5A). ER stress induction of CHOP expression occurred in both ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− cells. Another gene induced later in the ER stress response is GADD34, which is proposed to control the eIF2 kinase response through feedback by targeting the type 1 Ser/Thr protein phosphatase to eIF2 (16, 47, 48). GADD34 expression was induced after 6 h of ER stress in ATF3+/+ MEF cells (Fig. 6A). By comparison, ATF3 mutant MEF cells exposed to thapsigargin showed significantly lower GADD34 levels.

FIG. 6.

ATF3 facilitates enhanced GADD34 expression in response to ER stress and amino acid starvation. ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− MEF cells were treated with thapsigargin (Tg) (A), subjected to leucine starvation (B) for the indicated number of hours, or left untreated (0 h). The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane, and levels of ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, total eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P), GADD34, and actin were measured as indicated by immunoblot analysis.

In response to amino acid depletion, CHOP was absent in ATF3 mutant cells, while MEF cells expressing wild-type ATF3 showed full induction of the CHOP transcription factor (Fig. 6B). ATF3−/− cells also showed delayed expression of GADD34, with appreciable protein levels only after 9 h of leucine starvation. We conclude that during amino acid deprivation, ATF3 function is obligate for increased CHOP expression and, like ER stress, for full induction of GADD34 expression.

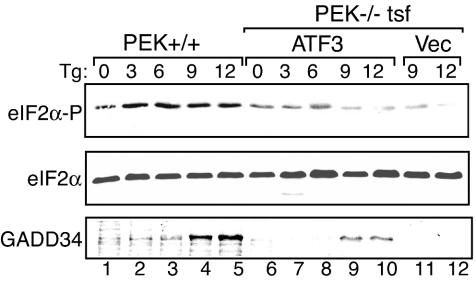

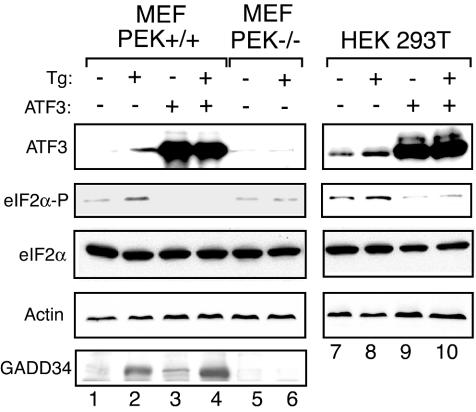

Analysis of the ATF4−/− and ATF3−/− cells supports the hypothesis that there is a sequential induction of bZIP transcription factors in response to eIF2 phosphorylation. To address this epistatic relationship, we transiently expressed ATF3 in PEK−/− cells and measured its impact on the levels of GADD34 expression in response to thapsigargin exposure. Elevated expression of ATF3 partially bypassed the requirement for PEK eIF2 kinase activity for induced GADD34 expression in response to ER stress (Fig. 7, lanes 9 and 10 versus lanes 11 and 12). Consistent with the idea that ATF3 facilitates expression of the GADD34 eIF2 phosphatase regulatory subunit, we found that transient ATF3 overexpression in PEK+/+ MEF cells or in HEK 293T cells led to reduced eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ER stress (Fig. 8). The HEK cell type has a higher basal level of ATF3 protein than that observed in MEF cells. Measurement of GADD34 protein in MEF cells showed that there were moderate levels of the phosphatase regulatory subunit in nonstressed PEK+/+ cells overexpressing ATF3 and no detectable GADD34 in vector-transfected MEF cells (Fig. 8, lane 1 versus lane 3). Furthermore, PEK+/+ MEF cells overexpressing ATF3 had higher levels of GADD34 in response to ER stress than did these MEF cells containing only the expression vector (Fig. 8, lane 2 versus lane 4). These results suggest that ATF3 can function in a mechanism of GADD34-mediated feedback inhibition of this translation control in different cell types.

FIG. 7.

ATF3 facilitates expression of GADD34 in response to ER stress. ATF3 was transiently expressed in PEK−/− MEF cells, and PEK+/+ and transfected (tsf) cells were subjected to the presence (+) or absence (−) of ER stress for the indicated number of hours. Vec indicates that the parent expression plasmid alone was introduced into the PEK−/− MEF cells. Whole-cell lysates were prepared from these transfected cells, and phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P), total eIF2α, and GADD34 levels were measured by immunoblot analysis. Tg, thapsigargin.

FIG. 8.

Overexpression of ATF3 reduces the levels of eIF2α phosphorylation during ER stress. ATF3 was transiently overexpressed in PEK+/+ MEF and HEK 293T cells, and these transfected cells or control PEK−/− cells were treated with thapsigargin (Tg) (+) for 6 h or not subjected to ER stress (−). ATF3 + indicates that this transcription factor was expressed in the indicated cell line, and ATF3 − indicates that only the expression vector was introduced into the cells. Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P), total eIF2α, ATF3, GADD34, and actin were measured by immunoblot analysis. The same amount of protein lysate was analyzed in each lane. In PEK+/+ MEF cells, the level of endogenous ATF3 induced by ER stress was lower than that measured in HEK 293T cells.

Differential DNA binding in response to ER stress and nutritional stress.

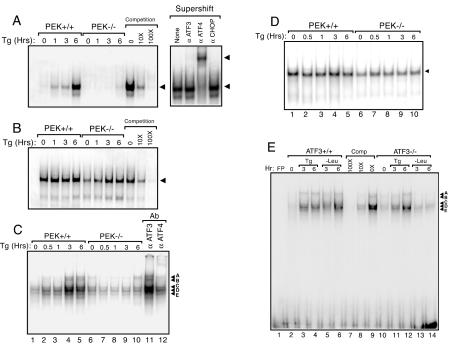

The nuclear fractions from PEK+/+ and PEK−/− cells treated with thapsigargin for up to 6 h were assessed for DNA binding affinity with the EMSA. ATF3 and ATF4 have been shown to heterodimerize with members of the C/EBP family (26). We measured DNA binding by such heterodimers by using an ATF-C/EBP composite binding site as previously described (22). Significant DNA binding was measured with lysates prepared from thapsigargin-treated PEK+/+ cells, with the highest levels following 6 h of ER stress (Fig. 9A). There was no further increase in ATF-C/EBP binding in cells subjected to 6 to 12 h of ER stress (data not shown). This DNA binding was specific for ATF-C/EBP transcription factors, as judged by reduced binding to the radiolabeled DNA upon addition of excess nonradiolabeled probe with the composite element (Fig. 9A). Furthermore, excess nonradiolabeled probe containing an NFκB binding site did not compete for binding of the ATF-C/EBP site (data not shown). There was also minimal binding to the ATF-C/EBP sequence with the nuclear preparation from PEK−/− cells. As a control, we used a DNA fragment containing the binding site for the OCT1 transcription factor and found similar levels of OCT1 binding activity in the PEK+/+ preparation during the course of thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 9B). With the PEK−/− lysates, we found a modest reduction in OCT1 binding levels in the absence of ER stress and after 1 h of thapsigargin treatment. Specificity for OCT1 DNA binding in the EMSA was established by competition with nonradiolabeled OCT1 site DNA.

FIG. 9.

Enhanced DNA binding by ATF4-C/EBP during ER stress requires PEK. (A to D) Nuclear lysates were prepared from PEK+/+ and PEK−/− MEF cells treated with thapsigargin (Tg) for the indicated time or in the absence of this ER stress agent (0 h). The same amount of lysate was used in EMSAs with radiolabeled double-stranded oligonucleotides containing an ATF-C/EBP composite binding site (A), an OCT1 binding site (B and D), or a GADD34 ATF-CREB binding site (C and E). Binding mixtures were separated by electrophoresis, and bound DNAs were visualized by autoradiographic exposures of the dried polyacrylamide gels. Bound DNA fragments in the EMSAs are indicated by an arrow. Competition indicates that nonradiolabeled competitor DNA was added at a 10× or 100× molar excess. (A) Supershift indicates that an antibody that specifically recognizes ATF3, ATF4, or CHOP was added to the EMSA binding mixture containing the nuclear lysate from PEK+/+ cells subjected to 6 h of ER stress. (C) In lanes 13 and 14, antibody specific to ATF3 or ATF4 was added to the EMSA binding mixture containing nuclear lysates prepared from PEK+/+ MEF cells subjected to 360 min of ER stress. (E) Nuclear lysates were prepared from ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− MEF cells subjected to ER stress (Tg) or to leucine deprivation (−Leu) for the indicated number of hours and assessed for binding to the GADD34 ATF-CREB binding site by EMSA. FP (free probe) indicates the GADD34 ATF-CREB DNA fragment without nuclear lysate. Competition (Comp) indicates that nonradiolabeled ATF-CREB competitor DNA was added at a 10× or 100× molar excess. Supershift experiments with ATF4, ATF3, or CHOP antibodies suggest that only ATF4 is present in the protein-DNA complexes with nuclear lysates prepared from leucine-deprived MEF cells (data not shown).

To determine the identity of the transcription factor(s) binding to the ATF-C/EBP DNA binding element, we assessed the mobility shift following the addition of a polyclonal antibody specific for ATF3, ATF4, or CHOP. Addition of an ATF4 antibody further retarded the migration of the radiolabeled DNA (Fig. 8A). By comparison, addition of an antibody specific to ATF3 or CHOP did not elicit a supershift in DNA migration. We used a DNA sequence containing an ATF binding site in the EMSA and found no enhancement of binding in PEK+/+ cells treated with thapsigargin for up to 12 h (data not shown). These results support the idea that elevated levels of ATF4 under ER stress conditions facilitate the stress response by forming heterodimers with one or more C/EBPs. These results are in agreement with earlier studies that suggested that ATF-CHOP heterodimers bind poorly to the ATF-C/EBP consensus sequence (13, 21, 53).

Given the importance of ATF3 in the expression of GADD34, we next characterized ATF binding in the GADD34 promoter. A radiolabeled ATF/CREB DNA element that is conserved among the mouse, human, and hamster GADD34 promoter regions was incubated with nuclear lysates prepared from PEK+/+ and PEK−/− MEF cells subjected to ER stress for up to 6 h (Fig. 9C) (38, 45). After 3 h of thapsigargin treatment, there was enhancement of five distinct protein-DNA complex bands, designated A to E, in PEK+/+ cells, while no increase was detectable in the PEK−/− nuclear lysates. Control OCT1-DNA binding remained unchanged during the course of the thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 9D). Addition of ATF4-specific antibody to the EMSA showed a supershift of the A and B bands, while addition of ATF3 antibody did not elicit a significant alteration in the ATF/CREB binding pattern (Fig. 9C, lanes 11 and 12).

We also characterized binding to the GADD34 ATF/CREB DNA element with lysates prepared from ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− MEF cells exposed to thapsigargin or leucine deprivation for 3 or 6 h (Fig. 9E). ER or nutritional stress induced DNA binding in the EMSA. Excess nonradiolabeled ATF/CREB probe reduced binding, while DNA containing an NFκB binding site did not compete for binding (Fig. 9E and data not shown). With nuclear lysates prepared from ATF3−/− cells deprived of leucine, there was a significant reduction in bound GADD34 ATF/CREB DNA compared to lysates prepared from similarly starved wild-type cells (Fig. 9E, lanes 4 and 5 versus lanes 12 and 13). Minimal DNA binding differences were observed between ATF3+/+ and ATF3−/− cells treated with thapsigargin (Fig, 9E). These results suggest that the ATF/CREB binding element contributes to increased expression of GADD34 expression in response to ER or nutritional stress. Furthermore, in response to leucine starvation, ATF3 directly or indirectly enhances binding at the ATF/CREB element in the GADD34 promoter.

DISCUSSION

eIF2 kinases induce a multifaceted program of gene expression in response to stress.

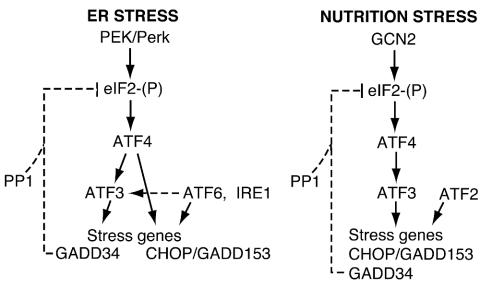

Phosphorylation of eIF2α contributes to a complex pattern of gene expression whereby multiple transcription factors differentially contribute to expression of stress-inducible genes. In this report, we show that ATF3 is integral to this stress response. ATF3 is induced in response to ER stress or amino acid deprivation, and deletion of the primary eIF2 kinase eliciting these stress responses blocked the synthesis of ATF3 mRNA and protein (Fig. 1, 2, and 4). Given the differences in timing for expression of ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP, we addressed the epistatic relationships among these transcription factors with MEF cells specifically carrying deletions of members of this stress response pathway. Deletion of ATF4 blocked the expression of ATF3 and CHOP in response to amino acid starvation and substantially reduced the expression of these transcription factors in response to ER stress (Fig. 5 and 6). As illustrated in Fig. 10, these results indicate that ATF4, whose levels are most rapidly induced following stress, directly or indirectly increases the transcription of ATF3 and CHOP. While deletion of ATF3 had no impact on ATF4 and CHOP expression during ER stress, loss of ATF3 function significantly reduced CHOP expression in response to starvation for amino acids. Together, these experiments support the model for sequential induction whereby ATF4 induces expression of ATF3, followed, at least in the case of amino acid deprivation, by ATF3 enhancement of CHOP expression (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

Cascade of transcription factors that induce stress gene expression in response to eIF2α phosphorylation. In response to ER stress, eIF2α phosphorylation by PEK induces ATF4 expression, which is required for increased expression of ATF3 and other stress genes. ATF3 is required for increased levels of GADD34, which directs the type 1 protein phosphatase (PP1) to dephosphorylate eIF2. ER stress is also recognized by membrane-associated ATF6 and IRE1, which function to activate the UPR, including GRP78 expression. ATF6 and IRE1 are proposed to work in conjunction with the eIF2 kinase stress pathway to enhance the expression of many stress genes, including CHOP/GADD153 and ATF3. During nutritional stress, the eIF2 kinase GCN2 induces the sequential expression of bZIP transcription factors ATF4, ATF3, and CHOP. ATF3 contributes to increased GADD34 expression, which contributes to feedback dephosphorylation of eIF2. Transcriptional activation by ATF3 may be indirect through protein-protein interactions. ATF4 is suggested to directly regulate stress gene expression during nutrient limitation. Analysis of MEF cells carrying a deletion of ATF2 indicate that this bZIP transcription factor is also required for CHOP expression in response to amino acid deprivation (8).

Expression of GADD34 has also been linked to eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 (16, 47, 48). We showed that deletion of ATF3 in MEF cells substantially reduced GADD34 levels in response to either ER stress or amino acid starvation (Fig. 6A and B). Overexpression of ATF3 partially bypassed the requirement for PEK and eIF2α phosphorylation for induced GADD34 expression in response to ER stress (Fig. 7). Further substantiating the linkage between ATF3 and expression of GADD34, overexpression of ATF3 increased levels of the GADD34 eIF2 phosphatase regulatory subunit and reduced levels of eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ER stress (Fig. 8). These results suggest that ATF3 functions directly or indirectly as an activator of GADD34 expression. This is noteworthy given that ATF3, despite its acronym, is thought to function as a transcriptional repressor through heterodimerization with other bZIP proteins (26).

ATF3 and ATF4 function in the activation of GADD34 and CHOP expression.

To further examine ATF3 function in GADD34 expression, we characterized an ATF/CREB binding site in the GADD34 promoter by EMSA. This DNA element gave five discernible protein-DNA complexes that were induced in response to ER stress and were fully dependent on PEK function (Fig. 10C). On the basis of supershift experiments with an antibody that specifically recognizes ATF4, the most slowly migrating bands, designated A and B, appear to involve bound ATF4 protein. Increased ATF4 binding activity is consistent with our observation that ATF4 has enhanced nuclear localization and increased binding to the consensus ATF-C/EBP consensus binding element following ER stress (Fig. 9A). This observation is also in agreement with a recent findings by Ma and Hendershot (45) that suggested that ATF4 can bind to the GADD34 promoter. Addition of an ATF3 antibody did not alter the ATF/CREB binding pattern, suggesting that, at least during ER stress, ATF3 does not bind directly to this GADD34 promoter region (Fig. 9C). In ATF3−/− MEF cells, the five protein-DNA bands were not induced in response to leucine starvation but were bound during ER stress (Fig. 9E). This suggests that both ATF4 and ATF3 participate in the expression of this eIF2 kinase-targeted gene and that additional regulatory elements in the GADD34 promoter participate at least in response to ER stress. Recently, Kilberg and colleagues (51) have also suggested that ATF3 and ATF4 may function jointly in the transcriptional induction of asparagine synthetase in response to nutritional stress.

Two sites in the CHOP promoter, an ER stress element and an ATF-C/EBP composite sequence, facilitate increased transcription (44). High levels of ATF4 expression were observed between 1 and 3 h of ER stress, with enhanced ATF4-C/EBP DNA binding by 6 h of thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 1B and 9A). This time frame of induced ATF4 activity, and the observation that deletion of ATF4 significantly reduced CHOP expression, suggests a role for ATF4 via the ATF-C/EBP site (Fig. 5) (30, 44). EMSA analysis of this CHOP ATF-C/EBP site indicated that there are at least four DNA-protein complexes induced by ER stress, and two complexes appear to involve ATF4 heterodimers, as judged by supershifting with an ATF4-specific antibody (44). The C/EBP(s) that associates with ATF4 does not appear to be C/EBPβ, a predominant C/EBP in fibroblasts that is proposed to be translationally induced by eIF2α phosphorylation (11), because increased CHOP expression during ER stress occurs in c/ebpβ−/− cells (78). However, overexpression of ATF4 or ATF3 alone is not sufficient to induce CHOP expression in PEK−/− cells, even under ER stress conditions (30; H. Jiang, unpublished observations). It is noteworthy that ATF2 is also required for CHOP expression in response to amino acid starvation conditions (8). These studies suggest that multiple bZIP transcriptional regulators, including ATF4, ATF3, and ATF2, work in concert to mediate activation of CHOP expression during nutrient limitation, and emphasize the differences in the mechanisms of CHOP regulation during amino acid starvation and ER stress (Fig. 10).

In addition to PEK, protein misfolding in the ER is also recognized by membrane-associated ATF6 and IRE1, which are proposed to contribute together to induction of the UPR, including GRP78 expression (29, 41) (Fig. 10). ER stress induces proteolytic cleavage of ATF6, releasing an amino-terminal fragment of the transcription factor that serves to activate the UPR (34, 42). Among these induced genes is XBP1, the mammalian homologue of yeast HAC1 (55, 59), which is also thought to function in the transcriptional activation of the UPR (10, 42, 74). However, XBP1 mRNA contains a 26-nucleotide insert that needs to be removed to facilitate translation. Splicing of XBP1 mRNA requires the RNase activity of the α isoform of IRE1. In response to ER stress, the induced protein kinase activity of IRE1α leads to elevated autophosphorylation and a change in protein conformation that enhances the endonuclease activity situated at the extreme carboxy terminus of IRE1α.

Our analysis of the UPR, as exemplified by GRP78 expression, indicates that at least a portion of this pathway can occur largely independently of PEK (Fig. 1) and distinguishes this transcriptional pathway from that mediating ATF4, ATF3, CHOP, and GADD34 expression. The UPR is restricted to stress in the ER, and GRP78 expression is unaffected by amino acid starvation, a stress condition that elevates ATF3 and CHOP expression. Mori and colleagues (49) suggested that there is ATF6-dependent and -independent gene expression in response to ER stress, further supporting the premise that different combinations of transcription factors mediate gene expression during ER stress. The fact that increased CHOP expression in response to ER stress occurs independently of ATF3 and at reduced, albeit measurable, levels in ATF4−/− cells suggests that ER stress-activated transcription factors such as ATF6 may contribute to CHOP expression via the ER stress element in the CHOP promoter (Fig. 5A, 6A, and 10).

In addition to regulation of stress gene expression, the eIF2 kinase PEK facilitates growth arrest in the G1 phase in response to ER stress (6). We found that overexpression of ATF3 in NIH 3T3 cells elicits this G1 arrest even in the absence of cellular stress (Jiang, unpublished). However, loss of ATF3 did not alter the cell cycle arrest during ER stress, again suggesting that ATF3 works in conjunction with additional regulatory proteins in the eIF2 kinase stress pathway.

eIF2 kinases and induction of ATF3 expression under different stress conditions.

PEK and GCN2 are primary eIF2 kinases that direct the cascade of transcription factors in response to ER stress or amino acid depletion, respectively (Fig. 1C and 4). It is noteworthy that under extended ER or nutritional stress conditions, there is enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation in the absence of these primary eIF2 kinases. For example, our analysis of MEF cells containing combined eIF2 kinase gene deletions suggests that GCN2 can serve as a secondary eIF2 kinase that is activated following 6 h of thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 1B). However, this delayed eIF2α phosphorylation does not necessarily lead to induced expression of bZIP transcription factors. In the case of ER stress in PEK−/− cells, the enhanced eIF2α phosphorylation detected following prolonged ER stress did not contribute to enhanced ATF4, ATF3, or CHOP expression (Fig. 1C). There was a modest increase in CHOP expression that followed delayed eIF2α phosphorylation in GCN2−/− cells subjected to leucine starvation (Fig. 4). Together, these results suggest that eIF2α phosphorylation per se is not sufficient to induce ATF4 and ATF3 and its target genes. Phosphorylation of eIF2α functions in conjunction with additional activating factors, such as ATF6 during ER stress, and the coordinate timing of these stress signals may be critical for increased stress gene expression.

ATF3 mRNA has been reported to be increased by a large number of different stress conditions in many different tissues and cultured cell systems (27). Some of the stress conditions that enhance ATF3 levels are linked to induction of eIF2α phosphorylation. For example, exposure of cultured cells to UV light induces ATF3 expression and was shown to enhance eIF2α phosphorylation by GCN2 and possibly PEK (18, 72). Induction of ATF3 and eIF2α phosphorylation has also been reported following exposure to ethanol, homocysteine, and oxidizing conditions (9, 15, 25, 27). Furthermore, inhibition of transcription or translation by actinomycin D and cycloheximide, respectively, can induce eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. 3) (40). Together, these studies suggest that activation of eIF2 kinases may occur in response to a larger and more diverse set of stress conditions than previously thought, and their function may have a general role in stimulating ATF4 and ATF3 and their target stress genes. Such stress genes may be important for coordinating common metabolic and stress remediation strategies for coping with cellular damage induced by the environmental stress. Additionally, the eIF2 kinase stress response pathway interfaces with other stress-related pathways, such as ATF6 and NFκB (29, 33, 40). Such combinatorial regulation would provide mechanisms by which to differentially regulate complex programs of stress gene expression that are best suited for the cellular insult.

Role of ATF3 under different stress conditions.

ATF3 can function as a homodimer or in association with C/EBPs and is proposed to have an important role in transcriptional repression. The target genes of ATF3 are not well understood. ATF3 has been reported to repress phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) promoters and autoregulate its own expression. Recent studies by Hai and colleagues have characterized the physiological responses of transgenic mice with targeted tissue expression of ATF3 and emphasized the importance of strictly controlling ATF3 levels (3). Overexpression of ATF3 in the liver led to organ dysfunction, with the transgenic mice displaying elevated levels of serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate transaminase, and bile salts. These transgenic animals also suffered from severe hypoglycemia, accompanied by reduced insulin in the serum and lowered adipocyte mass. The reduced levels of PEPCK and fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase mRNAs in the transgenic livers suggested that overexpression of ATF3 may contribute to defective glucose homeostasis by lowering gluconeogenesis. Elevated ATF3 expression in the pancreas led to mice with reduced islets of Langerhans (2).

It is interesting that disruption of appropriate eIF2α phosphorylation in mice can lead to many pathological conditions described for the ATF3 transgenic animals. For example, deletion of PEK (Perk) leads to impaired pancreatic function, including disrupted islets owing to catastrophic loss of islet beta cells (28, 75). The resulting neonatal insulin-dependent diabetes results in early death, and this underlying condition is also the hallmark of WRS, which results from loss of PEK (EIF2AK3) in humans (17). Kaufman and colleagues have replaced the genes encoding eIF2α with those encoding eIF2α-S51A in mice, creating a so-called knock-in animal that would be expected to approximate a loss of eIF2α kinase function (57). These eIF2α-Ser51A animals die within 1 day of birth because of severe hypoglycemia associated with defective gluconeogenesis. Impaired gluconeogenesis is at least in part due to significantly reduced levels of PEPCK, which is normally induced shortly after birth. Furthermore, eIF2α-Ser51A mice do not accumulate glycogen in their livers (57).

Given our finding that eIF2 kinase activity is required for increased expression of ATF3 in response to different stress conditions, it may appear contradictory that eIF2α-Ser51A mice and transgenic animals overexpressing ATF3 in the liver both have the hypoglycemic phenotype. However, we showed that overexpression of ATF3 in cultured MEFs or HEK 293T cells blocked eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ER stress (Fig. 7). Therefore, the physiological consequences of overexpressing ATF3 in transgenic animals may result at least in part from an impaired eIF2 kinase stress response. A similar explanation may also hold true for the common loss of islet beta cells observed in PEK−/− mice and transgenic mice overexpressing ATF3 in the pancreas. We do not understand the molecular basis for this ATF3 control, although it may involve GADD34, which inhibits eIF2α phosphorylation levels by feedback (16, 47). Increased levels of GADD34 that occur late in the stress response pathway serve to target a type 1 protein phosphatase catalytic subunit to phosphorylated eIF2α. The resulting dephosphorylation of this translation factor is thought to dampen the gene expression pathway when there is a sufficient level of stress gene expression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scot Kimball for generously sharing reagents and the Biochemistry Biotechnology Facility at Indiana University for technical support.

This study was supported in part by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R.C.W., GM49164 and GM643540; D.R.C., GM56957; T.H., DK59605; D.R., ES08681 and DK47119.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abastado, J. P., P. F. Miller, B. M. Jackson, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 1991. Suppression of ribosomal reinitiation at upstream open reading frames in amino acid-starved cells forms the basis of GCN4 translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:486-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen-Jennings, A. E., M. G. Hartman, G. J. Kociba, and T. Hai. 2001. The roles of ATF3 in glucose homeostasis. A transgenic mouse model with liver dysfunction and defects in endocrine pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29507-29514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen-Jennings, A. E., M. G. Hartman, G. J. Kociba, and T. Hai. 2002. The roles of ATF3 in liver dysfunction and the regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 277:20020-20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baltzis, D., L. Suiyang, and A. E. Koromilas. 2002. Functional characterization of pkr gene products expressed in cells from mice with a targeted deletion of the N-terminus or C-terminus of PKR. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38364-38372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertolotti, A., Y. Zhang, L. Hendershot, H. Harding, and D. Ron. 2000. Dynamic interaction of BiP and the ER stress transducers in the unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewer, J. W., and J. A. Diehl. 2000. PERK mediates cell-cycle exit during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12625-12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruhat, A., J. Averous, V. Carraro, C. Zhong, A. M. Reimold, M. S. Kilberg, and P. Fafournoux. 2002. Differences in the molecular mechanisms involved in the transcriptional activation of CHOP and asparagine synthetase in response to amino acid deprivation or activation of the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48107-48114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruhat, A., C. Jousse, V. Carraro, A. M. Reimold, M. Ferrara, and P. Fafournoux. 2000. Amino acids control mammalian gene transcription: activating transcription factor 2 is essential for the amino acid responsiveness of the CHOP promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7192-7204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai, Y., C. Zhang, T. Nawa, T. Aso, M. Tanaka, S. Oshiro, H. Ichijo, and S. Kitajima. 2000. Homocysteine-responsive ATF3 gene expression in human vascular endothelial cells: activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and promoter response element. Blood 96:2140-2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calfon, M., H. Zeng, F. Urano, J. H. Till, S. R. Hubbard, H. P. Harding, S. G. Clark, and D. Ron. 2002. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing of XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415:92-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calkhoven, F. C., C. Muller, and A. Leutz. 2000. Translational control of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ isoform expression. Genes Dev. 14:1920-1932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castelnau, P., M. Le Merrer, C. Diatlof-Zito, E. Marquis, M. J. Tete, and J. J. Robert. 2000. Wolcott-Rallison syndrome: a case with endocrine and exocrine pancreatic deficiency and pancreatic hypotrophy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 159:631-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, B. P., C. D. Wolfgang, and T. Hai. 1996. Analysis of ATF3, a transcription factor induced by physiological stresses and modulated by gadd153/Chop10. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1157-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, J.-J. 2000. Heme-regulated eIF2α kinase, p. 529-546. In N. Sonenberg, J. W. B. Hershey, and M. Mathews (ed.), Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 15.Clemens, M. J. 1996. Protein kinases that phosphorylate eIF2 and eIF2B, and their role in eukaryotic cell translational control, p. 139-172. In J. W. B. Hershey, M. B. Mathews, and N. Sonenberg (ed.), Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Connor, J. H., D. C. Weiser, S. Li, J. M. Hallenbeck, and S. Shenolikar. 2001. Growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible protein GADD34 assembles a novel signaling complex containing protein phosphatase 1 and inhibitor 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:6841-6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delepine, M., M. Nicolino, T. Barrett, M. Golamaully, G. M. Lathrop, and C. Julier. 2000. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-α kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat. Genet. 25:406-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng, J., H. Harding, B. Raught, A. Gingras, J. Berlanga, D. Scheuner, R. Kaufman, D. Ron, and N. Sonenberg. 2002. Activation of GCN2 in UV-irradiated cells inhibits translation. Curr. Biol. 12:1279-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong, J., H. Qiu, M. Garcia-Barrio, J. Anderson, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2000. Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA-binding domain. Mol. Cell 6:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fafournoux, P., A. Bruhat, and C. Jousse. 2000. Amino acid regulation of gene expression. Biochem. J. 351:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett, T. W., H. B. Eastman, J. L. Martindale, and N. J. Holbrook. 1996. Physical and functional association between GADD153 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta during cellular stress. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14285-14289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fawcett, T. W., J. L. Martindale, K. Z. Guyton, T. Hai, and N. J. Holbrook. 1999. Complexes containing activating transcription factor (ATF)/cAMP-responsive-element-binding-protein (CREB) interact with the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP)-ATF composite site to regulate Gadd153 expression during the stress response. Biochem. J. 339:135-141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez, J., I. Yaman, W. C. Merrick, A. Koromilas, R. C. Wek, R. Sood, J. Hensold, and M. Hatzoglou. 2002. Regulation of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation by eukaryotic initiation factor-2α phosphorylation and small upstream open reading frame. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2050-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fornace, A. J., D. W. Nebert, M. C. Hollander, J. D. Luethy, M. Papathanasiu, J. Fargnoli, and N. J. Holbrook. 1989. Mammalian genes coordinately regulated by growth arrest signals and DNA-damaging agents. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:4196-4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong, P., D. Stewart, B. Hu, C. Vinson, and J. Alam. 2002. Multiple basic-leucine zipper proteins regulate induction of the mouse heme oxygenase-1 gene by arsenite. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 405:265-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hai, T., and M. G. Hartman. 2001. The molecular biology and nomenclature of the activating transcription factor/cAMP responsive element binding family of transcription factors: activating transcription factor proteins and homeostasis. Gene 273:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hai, T., C. D. Wolfgang, D. K. Marsee, A. E. Allen, and U. Sivaprasad. 1999. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 7:321-335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harding, H., H. Zeng, Y. Zhang, R. Jungreis, P. Chung, H. Plesken, D. D. Sabatini, and D. Ron. 2001. Diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in Perk−/− mice reveals a role for translational control in secretory cell survival. Mol. Cell 7:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harding, H. P., M. Calfon, F. Urano, I. Novoa, and D. Ron. 2002. Transcriptional and translational control in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18:575-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harding, H. P., I. Novoa, Y. Zhang, H. Zeng, R. Wek, M. Schapira, and D. Ron. 2000. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 6:1099-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding, H. P., Y. Zhang, A. Bertolotti, H. Zeng, and D. Ron. 2000. Perk is essential for translation regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell 5:897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harding, H. P., Y. Zhang, and D. Ron. 1999. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397:271-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding, H. P., Y. Zhang, H. Zeng, I. Novoa, P. D. Lu, M. Calfon, N. Sadri, C. Yun, B. Popko, R. Paules, D. F. Stojdl, J. C. Bell, T. Hettmann, J. M. Leiden, and D. Ron. 2003. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 11:619-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haze, K., H. Yoshida, H. Yanagi, T. Yura, and K. Mori. 1999. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:3787-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hershey, J. W. B., and W. C. Merrick. 2000. Pathway and mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis, p. 33-88. In N. Sonenberg, J. W. B. Hershey, and M. B. Mathews (ed.), Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 36.Hinnebusch, A. G. 1997. Translational regulation of yeast GCN4. A window on factors that control initiator-tRNA binding to the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 272:21661-21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinnebusch, A. G., and K. Natarajan. 2002. Gcn4p, a master regulator of gene expression, is controlled at multiple levels by diverse signals of starvation and stress. Eukaryot. Cell 1:22-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hollander, M. C., Q. Zhan, I. Bae, and A. J. Fornace. 1997. Mammalian GADD34, an apoptosis- and DNA damage-inducible gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13731-13737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang, H. Y., C. Petrovas, and G. E. Sonenshein. 2002. RelB-p50 NF-κB complexes are selectively induced by cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein 1: differential regulation of Bcl-xL promoter activity by NF-κB family members. J. Virol. 76:5737-5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang, H.-Y., S. A. Wek, B. C. McGrath, D. Scheuner, R. J. Kaufmann, D. R. Cavener, and R. C. Wek. 2003. Phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 is required for activation of NF-κB in response to diverse cellular stresses. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:5651-5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman, R. J., D. Scheuner, M. Schroder, X. Shen, K. Lee, C. Y. Lin, and S. M. Arnold. 2002. The unfolded protein response in nutrient sensing and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:411-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee, K., W. Tirasophon, X. Shen, M. Michalak, R. Prywes, T. Okada, H. Yoshida, K. Mori, and R. J. Kaufman. 2002. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 16:452-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma, K., K. M. Vattem, and R. C. Wek. 2002. Dimerization and release of molecular chaperone inhibition facilitate activation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 kinase in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18728-18735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma, Y., J. W. Brewer, J. A. Diehl, and L. M. Hendershot. 2002. Two distinct stress signaling pathways converge upon the CHOP promoter during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J. Mol. Biol. 318:1351-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma, Y., and L. M. Hendershot. 2003. Delineation of a negative feedback regulatory loop that controls protein translation during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34864-34873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natarajan, K., M. R. Meyer, B. M. Jackson, D. Slade, C. Robertsw, A. G. Hinnebusch, and M. J. Marton. 2001. Transcriptional profiling shows that Gcn4p is a master controller of gene expression during amino acid starvation in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4347-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novoa, I., H. Zeng., H. P. Harding, and D. Ron. 2001. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α. J. Cell Biol. 153:1011-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novoa, I., Y. Zhang, H. Zeng, R. Jungreis, H. P. Harding, and D. Ron. 2003. Stress-induced gene expression requires programmed recovery from translational repression. EMBO J. 22:1180-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okada, T., H. Yoshida, R. Akazawa, M. Negishi, and K. Mori. 2002. Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem. J. 366:585-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oyadomari, S., A. Koizumi, K. Takeda, T. Gotoh, S. Akira, E. Araki, and M. Mori. 2002. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 109:525-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pan, Y., H. Chen, F. Siu, and M. S. Kilberg. 2003. Amino acid deprivation and endoplasmic reticulum stress induce expression of multiple activating transcription factor-3 species that, when overexpressed in HepG2 cells, modulate transcription by the human asparagine synthetase promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38402-38412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patil, C., and P. Walter. 2001. Intracellular signalling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus: the unfolded protein response in yeast and mammals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ron, D., and J. F. Habener. 1992. CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 6:439-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ron, D., and H. P. Harding. 2000. PERK and translational control by stress in the endoplasmic reticulum, p. 547-560. In N. Sonenberg, J. W. B. Hershey, and M. B. Mathews (ed.), Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, N.Y.

- 55.Ruegsegger, U., J. H. Leber, and P. Walter. 2001. Block of HAC1 mRNA translation by long-range base pairing is released by cytoplasmic splicing upon induction of the unfolded protein response. Cell 107:103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schauer, S. L., Z. Wang, G. E. Sonenshein, and T. L. Rothstein. 1996. Maintenance of nuclear factor-κB/Rel and c-myc expression during CD40 ligand rescue of WEHI 231 early B cells from receptor-mediated apoptosis through modulation of IκB proteins. J. Immunol. 157:81-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheuner, D., B. Song, E. McEwen, C. Liu, R. Laybutt, P. Gillespie, T. Saunders, S. Bonner-Weir, and R. J. Kaufman. 2001. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol. Cell 7:1165-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi, Y., K. M. Vattem, R. Sood, J. An, J. Liang, L. Stramm, and R. C. Wek. 1998. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 α-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translation control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7499-7509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sidrauski, C., and P. Walter. 1997. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell 90:1031-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siu, F., P. J. Blain, R. LeBlanc-Chaffin, H. Chen, and M. S. Kilberg. 2002. ATF4 is a mediator of the nutrient-sensing response pathway that activates the human asparagine synthetase gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24120-24127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sood, R., A. C. Porter, K. Ma, L. A. Quilliam, and R. C. Wek. 2000. Pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase (PEK) homologues in humans, Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans that mediate translational control in response to ER stress. Biochem. J. 346:281-293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sood, R., A. C. Porter, D. Olsen, D. R. Cavener, and R. C. Wek. 2000. A mammalian homologue of GCN2 protein kinase important for translational control by phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α. Genetics 154:787-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sovak, M. A., R. E. Bellas, D. W. Kim, G. J. Zanieski, A. E. Rogers, A. M. Traish, and G. E. Sonenshein. 1997. Aberrant nuclear factor-κB/Rel expression and the pathogenesis of breast cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2952-2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thornton, C. M., D. J. Carson, and F. J. Stewart. 1997. Autopsy findings in the Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Pediatr. Pathol. Lab. Med. 17:487-496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ung, T. L., C. Cao, J. Lu, K. Ozato, and T. E. Dever. 2001. Heterologous dimerization domains functionally substitute for the double-stranded RNA binding domains of the kinase PKR. EMBO J. 20:3728-3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vattem, K., K. A. Staschke, and R. C. Wek. 2001. Mechanism of activation of the double-stranded-RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR: role of dimerization and cellular localization in the stimulation of PKR phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α). Eur. J. Biochem. 268:3674-3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wek, R. C. 1994. eIF-2 kinases: regulators of general and gene-specific translation initiation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19:491-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wek, S. A., S. Zhu, and R. C. Wek. 1995. The histidyl-tRNA synthetase-related sequence in eIF-2α protein kinase GCN2 interacts with tRNA and is required for activation in response to starvation for different amino acids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4497-4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams, B. R. 1999. PKR: a sentinel kinase for cellular stress. Oncogene 18:6112-6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams, D. A., M. F. Rosenblatt, D. R. Beier, and R. D. Cone. 1988. Generation of murine stromal cell lines supporting hematopoietic stem cell proliferation by use of recombinant retrovirus vectors encoding simian virus 40 large T antigen. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3864-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willnow, T. E., and J. Herz. 1994. Homologous recombination for gene replacement in mouse cell lines. Methods Cell Biol. 43:305-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu, S., Y. Hu, J. L. Wang, M. Chatterjee, Y. Shi, and R. J. Kaufman. 2002. Ultraviolet light inhibits translation through activation of the unfolded protein response kinase PERK in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18077-18083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang, Y.-L., Y. F. L. Reis, J. Pavlovic, A. Aguzzi, R. Schafer, A. Kumar, B. R. G. Williams, M. Aguet, and C. Weissman. 1995. Deficient signalling in mice devoid of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. EMBO J. 14:6095-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshida, H., T. Matsui, A. Yamamotot, T. Okada, and K. Mori. 2001. XPB1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 107:881-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang, P., B. McGrath, S. Li, A. Frank, F. Zambito, J. Reinert, M. Gannon, K. Ma, K. McNaughton, and D. R. Cavener. 2002. The PERK eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase is required for the development of the skeletal system, postnatal growth, and the function and viability of the pancreas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3864-3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]