Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women. It seems that breast cancer patients benefit from meeting someone who had a similar experience. This study evaluated the effect of two kinds of interventions (peer support and educational program) on quality of life in breast cancer patients.

METHODS:

This study was a controlled clinical trial on women with non-metastatic breast cancer. The patients studied in two experimental and control groups. Experimental group took part in peer support program and control group passed a routine educational program during 3 months. The authors administered SF-36 for evaluating the quality of life pre-and post intervention. Also, patient's adherence was assessed by means of a simple checklist.

RESULTS:

Two groups were similar with respect of age, age of onset of the disease, duration of having breast cancer, marital status, type of the treatment receiving now, and type of the received surgery. In the control group, there were statistically significant improvements in body pain, role-physical, role-emotional and social functioning. In experimental group, role-physical, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health showed significant improvement. Vitality score and mental health score in experimental group was significantly higher than that of the control group, both with p < 0.001. Also, it was shown that adherence was in high levels in both groups and no significant difference was seen after the study was done.

CONCLUSIONS:

According to the results of this study, supporting the patients with breast cancer by forming peer groups or by means of educational sessions could improve their life qualities.

KEYWORDS: Breast Cancer, Peer Group, Adherence, Quality of Life

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer in women with five year survival of almost 85% after diagnosis.1 In Iran, it consists of 22.6% of all cancers of women. Most women are diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 35 to 44 which is 10 years below the average age of onset of the disease in western countries.2 The survival rate has significantly increased due to common methods of treatment but the negative effects of these kinds of therapies on patients’ survivals have not been considered.2 Almost one third of patients with cancer suffer from a known psychological problem which needs proper intervention as well as socio-emotional supports in each stage of disease.3 Loss of each or both of the breasts would cause the patient to feel a defect in her body and would change her self-body- imaging and cause feeling loss of not only self-confidence also feminine attraction, leading to anxiety, depression, despair, shame (embarrassment), fear of recurrence of the cancer and death.2 Formation of interventional groups with psycho-social approach in the last two decades has been brought into consideration in order to help patients cope better with psychosocial consequences of their disease. These supportive groups can have various approaches, methods and conditions and include educational groups or peer groups, in which taking part would help patients defeat the fear of their unknown future and fear of death by means of getting to know each other and sharing their experiences.3 Peer groups with psycho-social approach consisted of patients suffering from the same disease are formed on the basis that meeting people who have experienced this disease could be of much help.4

Studies have shown that these interventions can change the consequence of the disease by various means. Social comparison theory states that by expressing personal experiences to people who have gone through the same experiences and making new opportunities to help similar people would not only normalize patient's experience also make a positive role, reinforce (augment) health-promoting behaviors and enhance self-confidence in patients. Various other theories also imply that these types of supports will increase the quality of patient's lives and even can increase their survival rates.5

Another important issue in patients’ treatment is adherence. Especially in chronic diseases which need long term treatment and frequent follow ups, adherence rate has been much less in comparison to acute conditions. In several studies, it has been shown that adherence rate would drop most dramatically six months after initiation of therapy.6 Investigations have shown that despite life-threatening nature of breast cancer, persistence and adherence in therapy would drop gradually, constituting a loss in health opportunity and waste of resources.7 Not so much studies have been done on the role of peer groups in patients with breast cancer and only a few studies have shown that the emotional support could have a positive effect on increasing the rate of adherence.8

Due to few studies assessing the role of peer groups in different aspects of life quality and especially adherence in patients with breast cancer and also comparing it with other supportive methods, the aim of this study was to form peer groups and evaluate their effects on the aspects mentioned above as well as comparing this method with educational programs in order to find out whether this type of intervention would have a positive role in patients’ outcomes.

Methods

This study was a non-randomized controlled clinical trial on women diagnosed with breast cancer, conducted between June 2010 and December 2010 in Breast Diseases Research Center in Isfahan (IRCT201102055766N1).

Ethical Issue

The proposal of this study was approved in Vice Chancellor for Research Affairs of Faculty of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Written and informed consent was obtained from all patients. Also, the confidentiality of information managed carefully by researchers.

Participants

The samples were enrolled by referring to the private offices of some of the oncologists in Isfahan, extracting the phone number of patients who had the inclusion criteria for this study according to their order of visits. Some patients were selected and they were contacted and invited to participate in the study. It was predictable that some patients would refuse to take part in these sessions and some would discontinue. So, the extracted number of patients was 3 times more than the calculated sample size. Also, the control group included patients with breast cancer who registered and started educational programs in breast diseases research center; meanwhile, the peer groups were formed. The sample size was calculated 28 in each group according to a similar study9 with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2. With prediction of 20% loss in each group, 34 patients were placed in each group.

The studied sample consisted of 68 patients with breast cancer selected through convenience sampling method considering inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included women with breast cancer with 20 to 65 years of age who have had mastectomy 6 months to 2 years before and at the time of study were receiving therapy – whether radiotherapy or medical treatment. Patients should have been be in stage II and III of nonmetastatic breast cancer, who had no chronic disabling underlying condition (such as major depression or any other condition which would prevent them from participating in sessions). Also, the patients should meet the literacy needed to fill in the questionnaires and have never had participated in such supportive programs before. Exclusion criteria were patients who would discontinue voluntarily, patients developing any mental or physical disease which would prevent them from continuing the study, those who were absent in 2 consecutive sessions and those who got aware of the other group and had meanwhile took part in their sessions.

The Experimental group

In experimental group, 4 patients were chosen voluntarily as group leaders and participated in 8 sessions held by the co-psychiatrist of the project. The content of these sessions was simple knowledge about coping with stress and worries, gaining self-awareness and mindfulness. The purpose was to prepare these group leaders for the management of sessions and prevent any inappropriate topics and solutions which could have been brought on during each session. Patients were divided into two groups of 17 in order to participate in peer groups. In each group, two of the leaders were in charge of holding and conducting the sessions. The meetings were held twice-monthly (total number of 6 sessions during intervention) and in each session, the patients shared their experiences from the disease, worries, cons and pros of the disease and their hopes with other members and listened to others experiences. In some of the sessions, the project executor also took part in order to ensure the sessions are held in correct manner and that none of the control groups took part in these sessions. Each session lasted from an hour and half to 2 hours. The patients were encouraged to contact each other out of sessions too, and support each other to help manage their anxiety and stress.

The Control group

Also, in the control group the patients participated in 6 educational sessions held on their disease, its treatment and complications, appropriate nutrition and similar subjects. Each educational session lasted about an hour and half and was presented by the associated specialist.

Data collecting methods and data analyzing

In order to evaluate life quality, SF36 questionnaire, the valid and known questionnaire for surveying life quality was used. The validity and reliability of the Persian translated version has been confirmed before.10 This questionnaire evaluates the status of health in 2 separate components, mental and physical. The physical component summary has 4 scales of physical functioning (PF) with 10 questions, role limitation due to physical problems (RP) with 4 questions, body pain (BP) with 2 questions and general health (GH) with 5 questions. Also, the mental component summary consists of 4 scales of vitality (VT) with 4 questions, social functioning (SF) with 2 questions, role limitation due to emotional problems (RE) with 3 questions and mental health (MH) with 5 questions, and one question about general health perception. So, this questionnaire surveys health condition in 8 subscales. In each of these 8 subscales, scores are calculated separately and its range varies from 0 to 100. Higher score in each subscale suggests better condition and lower score shows some problems within that special subscale. In order to assess the adherence, a checklist containing 2 questions was used, which determined patients’ adherence in medical therapy and physical exams. The patients check “following medical orders” in 3 scales of “most often, sometimes, never”. After the questionnaires were completely filled out at the beginning of the trial and after 3 months, the data was analyzed using SPSS software version 18. Chi square test, paired sample t-test, independent t-test, MANCOVA and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used for analyzing the data. The latest method was used for variables without normal distribution (RE and RP) according to Kolmo-gorov-Smirnov test.

Results

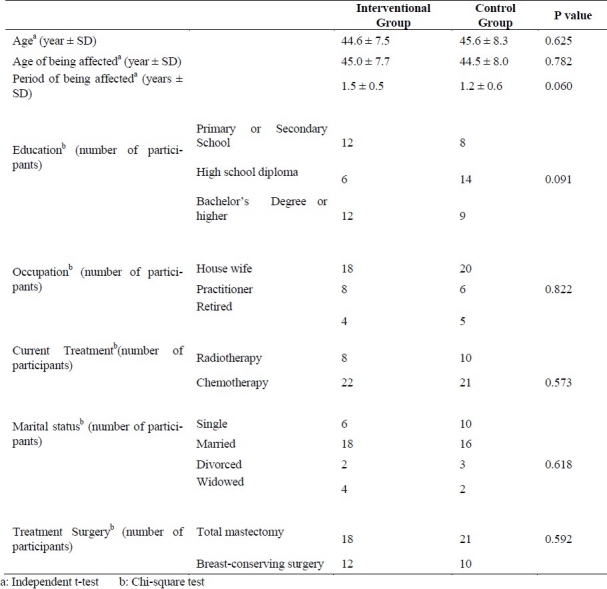

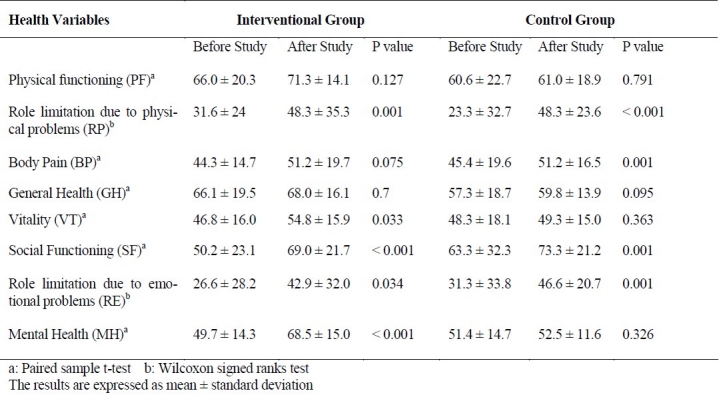

After the study was started, 4 patients in the experimental group and 3 patients in the control group were excluded due to lack of interest in continuing the study or participating irregularly in the sessions. So the total number of 30 patients in experimental group and 31 patients in control group completed the study. As shown in Table 1, experimental and control groups were similar in respect of age, age of onset of the disease, duration of having breast cancer, marital status, type of the treatment receiving now, and type of the received surgery. Also, the score of life quality in each of its 8 subscales is shown separately in both interventional and control groups in Table 2. In order to evaluate normal distribution of data for all quantitative variables, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was done. Life quality scores of both groups in each of 8 subscales were calculated and were compared with the preintervention scores. In the control group, there was a statistically significant improvement in BP, RP, RE and SF. In experimental group, RP, VT, SF, RE and MH showed significant improvement (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics and some variables between the two groups

Table 2.

Comparison of quality of life components before and after the study between the two groups

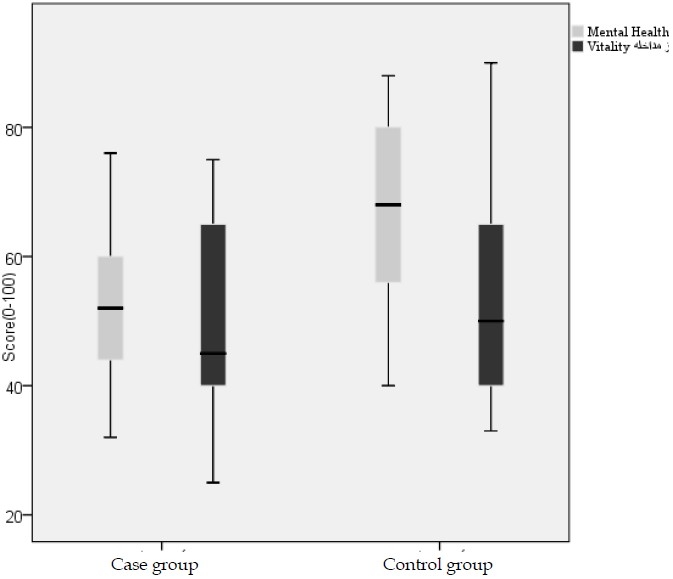

Comparison of the experimental and control groups with MANCOVA test and considering 8 subscales of life quality before the study as confounding variables, it was determined that VT score and MH score in experimental group were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.000, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean mental health and vitality scores between the two groups

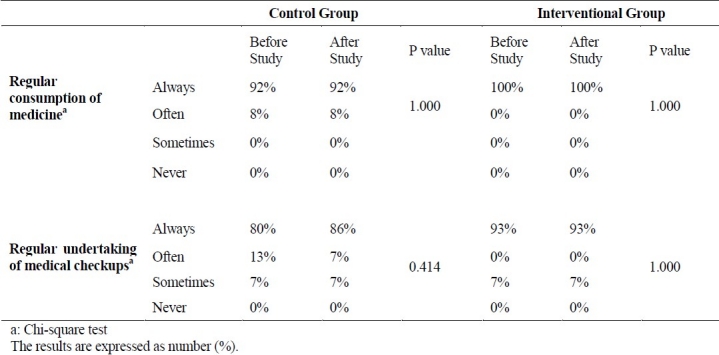

Also, it was shown that adherence rate is high in both groups and no significant difference was seen after the study was done (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of adherence to treatment between control and experimental groups before and after the study

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that both social supports from other patients as well as educational programs can be effective in increasing life quality of patients with breast cancer. In the experimental group, mainly the mental components of the life quality such as SF, VT, RE, and MH showed significant improvement regarding pre-study indices. Also, the experimental group had a better condition as far as VT and MH was concerned in comparison to control group, which could be suggestive of the importance of the use of this method for improving mental health in breast cancer patients. In similar studies also, this method was also implied to be effective in improving life quality of patients. In a study on patients participating in the Reach to Recovery program which is a peer modeling type, it was demonstrated that those women who took part in the program would have a better condition in VT, MH, and SF domains compared to normal women of the population.9 Also, in another study, despite the fact that it was done on patients with metastasis and the study instruments differed from the current study, patients who were involved in supportive programs including peer groups, had significantly better conditions in mood status as well as decrease in depression signs and anxiety and reduction in pain in comparison to the control group who had not received these programs.11

Although in most studies, the positive impact of peer groups is more perceptible in mental and emotional aspects, in this study the intervention revealed positive effect on one domain of physical problems (RP) which could be the result of physical improvement due to proper medical treatment and increased physical abilities of patients rather than the intervention itself. Moreover, there has been a positive impact on disease outcome and psychological conditions of the patients with other chronic problems such as diabetes12 and AIDS by participating in peer support groups.13

Several studies have been conducted to assess the effect of educational interventions on life quality improvement. Current study revealed that in comparison to the control group, physical health aspects such as BP, RP, as well as some of the mental health aspects such as SF, RE showed significant improvement in the experimental group. These positive effects were also implied in other studies, though in some of comparative studies, the results differed from those of this study. For instance, in a study evaluating life quality and adjustment to cancer in women with breast cancer in two groups of educational and peer group interventions, it was revealed that consistent positive effects on VT, MH, SF, PH, RE, and RP were seen in the educational group both immediately and 6 months after the intervention while the peer group showed deterioration in condition in indices such as VT and SF.14 In several other studies, the patients benefited from these programs under some special occasions or the interventions might have had negative effects on their life qualities. For example, in a study in women who received enough support from their husbands, life quality was not improved with participating in these programs and even using peer groups reduced their life qualities. This study also demonstrated that life quality improved in those women who did not receive enough support from their husbands by participating in educational programs or peer groups and that any use of these interventions should be considered depending on patients conditions.15

There also have been several studies conducted on peer group impact on life quality of breast cancer patients in Iran, revealing the fact that this kind of intervention would increase life quality of experimental group in comparison to control group. In one of these studies, patients undergone surgery were enrolled in one-one peer support program with similar patients who had similar condition and this intervention improved their life quality in mental and social aspects but was of no benefit in physical and spiritual aspects.16 Also, another study conducted in Iran showed this kind of intervention improved patients’ quality of life in all aspects and the positive results persisted even 2 months after the intervention.2

The greatest problem of the current study was lack of randomization of patients for each group, which was due to small number of patients who had the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate. But as there was no significant difference in demographic characteristics and treatment conditions, this issue has probably not impaired the results obtained. Another limitation in this study was the lack of follow up in patients after the intervention to evaluate whether the effects of this study last long enough or not. This can be achieved by designing other studies in future and following up the patients. It might be possible that participants of educational programs would have supported each other emotionally due to making communications and this could have affected the results of this group. Although the researchers participated in some of their sessions and it was revealed that these communications and supports are not in the level that could have possibly affected the results. All together, it seems that supporting the patients with breast cancer during or after treatment by forming peer support groups or by increasing knowledge by means of educational sessions could have positive effects on their life quality.

Authors’ Contributions

Afsaneh Malekpour and Ziba Farajzadegan carried out the design and coordinated in the study conduct, participated in most of the experiments and prepared the manuscript. Fariborz Mokarian provided assistance in the design of the study, coordinated and carried out all the experiments and Ahmadreza Zamani provided assistance in the design of the study and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for financial support (research project number 389164). We also express our gratitude to Ms. Javaheri, the team psychologist, for her help to educate the leaders of intervention group and Ms. Asemi for her assistance in contacting and inviting patients for our study.

Footnotes

Financial Support

This study was funded by Research Deputy of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Stanton AL, Ganz PA, Kwan L, Meyerowitz BE, Bower JE, Krupnick JL, et al. Outcomes From the Moving Beyond Cancer Psychoeducational, Randomized, Controlled Trial With Breast Cancer Patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6009–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharif F, Abshorshori N, Tahmasebi S, Hazrati M, Zare N, Masoumi S. The effect of peer-led education on the life quality of mastectomy patients referred to breast cancer-clinics in Shiraz, Iran 2009. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):74. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weis J. Support groups for cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(12):763–8. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rankin N, Williams P, Davis C, Girgis A. The use and acceptability of a one-on-one peer support program for Australian women with early breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53(2):141–6. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell HS, Phaneuf MR, Deane K. Cancer peer support programs--do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to Medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkins L, Fallowfield L. Intentional and non-intentional non-adherence to medication amongst breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(14):2271–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMatteo MR. Social Support and Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment: A Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–18. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews BA, Baker F, Hann DM, Denniston M, Smith TG. Health status and life satisfaction among breast cancer survivor peer support volunteers. Psychooncology. 2002;11(3):199–211. doi: 10.1002/pon.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):875–82. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin P, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(24):1719–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HF, van den Borne BH. Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molassiotis A, Callaghan P, Twinn SF, Lam SW, Chung WY, Li CK. A pilot study of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and peer support/counseling in decreasing psychologic distress and improving quality of life in Chinese patients with symptomatic HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16(2):83–96. doi: 10.1089/10872910252806135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helgeson VS, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Education and Peer Discussion Group Interventions and Adjustment to Breast Cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(4):340–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helgeson V, Cohen S, Schulz R, Yasko J. Group support interventions for women with breast cancer: who benefits from what? Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):107–14. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taleghani F, Babazadeh SSH, Tabatabaiyan SM, Mosavi SM. P79 Effect of one-one peer support programme on quality of life of Iranian women with breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(Suppl 1):S47. [Google Scholar]