Abstract

A critical issue in understanding receptor tyrosine kinase signaling is the individual contribution of diverse signaling pathways in regulating cellular growth, survival, and migration. We generated a functionally and biochemically inert c-Kit receptor that lacked the binding sites for seven early signaling pathways. Restoring the Src family kinase (SFK) binding sites in the mutated c-Kit receptor restored cellular survival and migration but only partially rescued proliferation and was associated with the rescue of the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase, Rac/JNK kinase, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3 kinase)/Akt pathways. In contrast, restoring the PI-3 kinase binding site in the mutated receptor did not affect cellular proliferation but resulted in a modest correction in cell survival and migration, despite a complete rescue in the activation of the PI-3 kinase/Akt pathway. Surprisingly, restoring the binding sites for Grb2, Grb7, or phospholipase C-γ had no effect on cellular growth or survival, migration, or activation of any of the downstream signaling pathways. These results argue that SFKs play a unique role in the control of multiple cellular functions and in the activation of distinct biochemical pathways via c-Kit.

The functional or biochemical consequence(s) of activation of diverse individual biochemical pathways via receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in hematopoietic cells is poorly understood. Furthermore, no studies have directly addressed whether distinct Src homology 2 (SH2) binding sites in hematopoietic cell-associated RTKs result in distinct, generic or overlapping biological and functional outcomes. The RTK c-Kit plays an essential role in regulating proliferation, survival, and migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells during development as well as in adults (2, 3, 25). In addition to being expressed on hematopoietic cells, c-Kit is also expressed on cells of nonhematopoietic origin, including melanocytes, primordial germ cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal (3). In hematopoietic cells, c-Kit can act synergistically with other growth factor receptors to promote survival, proliferation, and differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages (2, 3, 25). At this time, it is unclear whether c-Kit-mediated survival, proliferation, and/or migration of hematopoietic cells is regulated via the activation of unique signaling pathways or due to quantitative differences in generic signaling output (36).

Activated c-Kit binds signaling molecules at specific tyrosine residues: phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) at tyrosine 728 (13, 28), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3 kinase) at tyrosine 719 (35), Src family kinases at positions 567 and 569 (24, 26, 39, 41), Grb2 at tyrosine 702 (38), and Grb7 at tyrosine 934 (38). Other classes of signaling proteins have also been reported to bind activated c-Kit with unknown sequence specificity (7, 9, 19, 32, 44). Studies of multiple cell types have shown that c-Kit molecules carrying tyrosine (Y)-to-phenylalanine (F) (Y→F) mutations at critical residues fail to bind the associated signaling molecules and consequently fail to activate these signaling pathways (2, 25). Furthermore, single point mutations in critical tyrosine residues can affect c-Kit functions to various degrees (2, 25).

Although informative, this approach of assessing the function of a signaling pathway by uncoupling one or two binding proteins from a receptor, when all other signaling molecules can bind and activate the receptor can be problematic. In particular, if the SH2-containing adaptor proteins and enzymes that still bind to the mutant c-Kit compensate for the loss of a binding protein, then the relative importance of the various c-Kit-associated proteins in regulating cellular functions and activating downstream molecules could be underestimated. We have constructed and expressed several c-Kit mutant receptors with the ability to activate only a single biochemical pathway upon ligand stimulation. In the basic mutant version of this receptor (naked receptor), seven tyrosine (Tyr) residues that bind SH2 signaling proteins were altered, in various combinations, to phenylalanine. The naked c-Kit mutant receptor with Tyr→Phe substitutions at seven sites or with single Tyr residues restored to the naked c-Kit mutant receptor (add-back c-Kit receptors), were tested for their ability to induce the activation of distal signaling proteins and cellular functions, including survival, proliferation, and migration. We demonstrate that the Src kinase pathway plays a unique role in the control of multiple c-Kit functions and that this pathway alone is sufficient to restore the activation of Ras, PI-3 kinase, Erk, Rac, JNK, and AKT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

G1E-ER2 and 32D cells have been previously described (14, 22).

Construction of WT and mutant CHRs.

The construction of a chimeric c-Kit receptor (CHR) has been previously described (37). To generate a c-Kit receptor in which tyrosines at positions 567, 569, 702, 719, 728, 745, and 934 were replaced with phenylalanine, the NotI-XhoI wild-type (WT) CHR DNA fragment (2.9 kb) spanning the sites to be mutated was subcloned into Bluescript vector. QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Menasha, Wis.), and primers containing the appropriate mutations were used to mutate tyrosine residues at positions 567, 569, 702, 719, 728, 745, and 934 to phenylalanine. These mutations were verified by sequencing. The fragments were released from Bluescript and religated into the NotI-XhoI site of MIEG3 retroviral vector (45). To restore the phenylalanine residues at positions 567, 569, 702, 719, 728, 745, and 934 individually back to tyrosines, a c-Kit receptor lacking all seven tyrosine residues (naked c-Kit receptor) was used as a template to individually restore the phenylalanines to tyrosines. Utilizing this bicistronic retroviral vector, we inserted the WT and mutant CHR cDNAs upstream of the internal ribosome entry site and the enhanced green fluorescence (EGFP) gene (see Fig. 1).

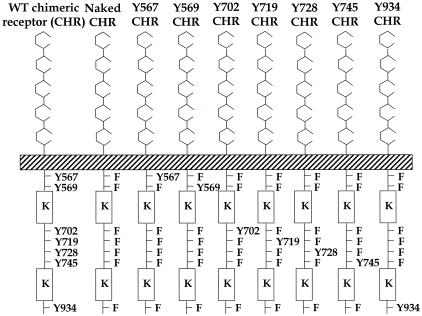

FIG. 1.

Schematic structures of WT and mutant chimeric c-Kit receptors. The CHR consists of the ligand binding domain of the human M-CSF receptor. The transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of the CHR consist of the c-Kit receptor. The kinase domain (K) is indicated. In the naked c-Kit CHR, tyrosines (Y) at indicated positions were changed to phenyalanine (F). In the mutant add-back c-Kit CHRs, F at indicated positions in the naked c-Kit CHR were restored to Y.

Expression of WT and mutant CHRs in G1E-ER2 and 32D cells.

To produce WT and mutant CHR viral supernatants for infection of G1E-ER2 and 32D cells, Phoenix ecotropic cells were transiently transfected with WT retrovirus or various mutants of c-Kit retroviral constructs using the Lipofectamine Plus reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection, filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size membranes, and used. Cells were infected with 2 ml of virus supernatant in the presence of 8 μg of Polybrene per ml. Virus-infected cells were harvested 48 h later, sorted by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter, and expanded in culture. G1E-ER2 and 32D cells expressing similar levels of EGFP and CHRs were utilized to perform all the experiments described in these studies. Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described previously (37).

Proliferation, survival, and migration assays.

The effect of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) on proliferation was analyzed using a thymidine incorporation assay (37). The effect of M-CSF on survival was assayed by staining the cells with annexin V conjugated to phycoerythrin (annexin V-PE) according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD/Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Tissue culture plates (24-well plates) were utilized for these experiments. 32D cells (5 × 105 cells/well) were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of M-CSF. Subsequently, cells were harvested and stained with annexin V-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. Migration was evaluated using a transwell migration assay. Briefly, 3 × 105 32D cells in 100 μl of serum-free chemotaxis medium (Iscove modified Dulbecco medium [IMDM] containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin) were loaded onto each transwell filter (8-μm-pore-size filter) (Costar, Boston, Mass.) (24-well cell clusters). Filters were then placed in wells containing 500 μl of serum-free chemotaxis medium supplemented with or without M-CSF. After 4-h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the upper chamber was carefully removed, and the cells in the bottom chamber were resuspended and counted with a hemocytometer.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation analyses.

32D cells expressing various mutants of c-Kit were starved of serum and growth factors for 6 to 10 h. Starved cells were resuspended in IMDM and stimulated with M-CSF or interleukin-3 (IL-3). Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (37). Activation of AKT and Erk mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase was determined by using phospho-specific antibodies (Cell Signaling, Beverley, Mass.). Total AKT, Erk, and p85α protein expression was determined using antibodies against AKT, Erk, Fyn, JNK, and p85α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.). Starved and M-CSF-stimulated 32D cells were analyzed for PI-3 kinase activity by previously published methods (4).

Ras and Rac activation assays.

Ras and Rac were activated by depriving 32D cells of serum and growth factors and then stimulating the cells with M-CSF or IL-3. Activation was determined by using a Ras and Rac activation assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RESULTS

Construction of mutant c-Kit receptors.

We have previously reported the construction of a chimeric c-Kit receptor with altered ligand binding specificity used to examine the roles of c-Kit in mediating proliferation, survival, and migration in erythroid and mast cells (37). The chimeric c-Kit receptor approach was used to bypass endogenous c-Kit receptor expression in erythroid and mast cells (37). This receptor contains the extracellular ligand binding domain of the human M-CSF receptor and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic signaling domains of the murine c-Kit (Fig. 1) (37). The extracellular domain of the M-CSF receptor was chosen, because the M-CSF receptor and c-Kit are highly related RTKs of the same subfamily but possess different ligand binding specificities (43). Therefore, the chimeric c-Kit receptor we constructed has the signaling activity of c-Kit but is activated by binding M-CSF (37). We refer to this as the wild-type (WT) chimeric receptor, designated CHR, because the c-Kit cytoplasmic signaling domain is intact. We have previously demonstrated that this receptor functionally and biochemically behaves in a fashion similar to the WT endogenous c-Kit receptor (37). This chimeric receptor approach used to investigate the role of a specific signaling pathway in nonhematopoietic cells, such as the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), has been previously described (8, 10).

Utilizing this receptor as a template, we constructed a c-Kit receptor in which seven tyrosine residues were replaced with phenylalanine residues at positions that have been previously demonstrated to bind and activate distinct immediate-early signaling pathways upon stem cell factor (ligand for c-Kit) stimulation. We designated this the naked chimeric c-Kit receptor (Fig. 1). This receptor contains Y→F mutations at residues 567, 569, 702, 719, 728, 745, and 934 (Fig. 1; numbers correspond to the amino acid position in the full-length murine c-Kit). These mutations prevent the activation of PI-3 kinase (position 719) (35), Src kinase family members (positions 567 and 569) (24, 26, 39, 41), PLC-γ (position 728) (13, 28), Grb2 (position 702) (38), and Grb7 (position 934) (38). We also mutated an additional tyrosine residue at position 745. Utilizing the naked c-Kit receptor as a template, we constructed a series of eight add-back chimeric c-Kit receptors in which phenylalanine residues at positions 567, 569, 567 and 569, 702, 719, 728, 745, and 934 were restored back to tyrosine residues (Fig. 1).

Expression of mutant c-Kit receptors engineered to activate a single biochemical pathway.

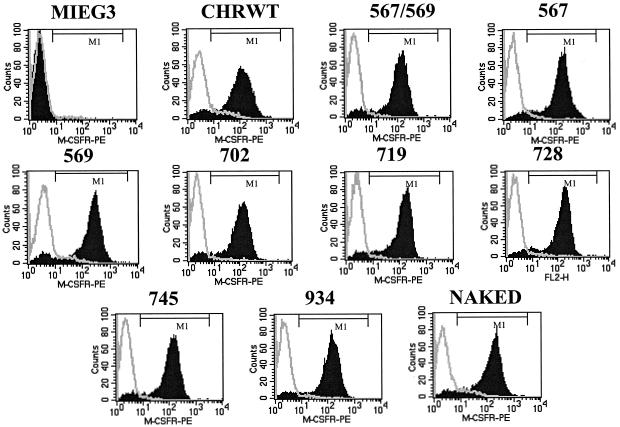

Mutant c-Kit receptors containing the appropriate mutations were cloned into MIEG3, a bicistronic retroviral vector that expresses the EGFP via an internal ribosome entry site as previously described (37). Viral supernatants were generated as described previously (37). Viral supernatants were used to infect an erythroid cell line (G1E-ER2) and a myeloid cell line (32D). Both G1E-ER2 and 32D cells lack the expression of endogenous M-CSF receptor (22, 37). EGFP-positive cells were sorted to homogeneity and used to perform functional and biochemical assays. Flow cytometry was used to determine the expression of chimeric c-Kit mutant receptors in transduced 32D and G1E-ER2 cells. Figure 2 demonstrates similar levels of expression of the chimeric c-Kit mutant receptors used in this study. The level of receptor expression achieved in our system is similar to that reported in primary hematopoietic cells (21, 39). Cells expressing similar levels of c-Kit mutant receptors were utilized in subsequent studies. The phosphorylation of various CHR mutants examined in these studies was comparable to that of WT CHR, except for naked CHR (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Expression of the mutant c-Kit CHRs. Cells expressing the indicated c-Kit CHR were stained with a PE-conjugated antibody against M-CSF receptor (M-CSFR) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression of M-CSF receptor (black histograms) for all 10 CHRs as well as for cells infected with the MIEG3 vector alone is shown. Light gray lines indicate staining with isotype control antibody.

Consequences of restoring individual early signaling pathways in c-Kit on proliferation.

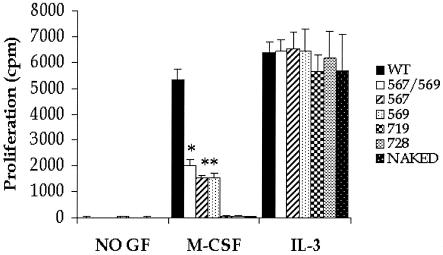

To determine the effect of restoring individual biochemical pathways in the naked c-Kit receptor on M-CSF-induced proliferation, we stimulated 32D cells expressing similar levels of c-Kit mutant receptors and measured proliferation after 48 h by thymidine incorporation. As shown in Fig. 3, only the c-Kit mutants in which the Src binding sites (positions 567, 569, and 567 and 569) were restored demonstrated any degree of rescue (∼30 to 40%) in proliferation. A modest but significant difference in the rescue of c-Kit-induced proliferation was observed in cells expressing the double Src mutant (positions 567 and 569) compared to the single Src mutants (position 567 or 569) (Fig. 3). To confirm that the lack of proliferation via any of the mutant chimeric c-Kit receptors was not due to an overall defect in the proliferative ability of IL-3-dependent 32D cells, we measured thymidine incorporation in cells expressing various CHR mutants in response to IL-3. As seen in Fig. 3, despite defective M-CSF-induced proliferation via c-Kit CHR mutants, IL-3-dependent proliferation appeared intact in all c-Kit mutant-expressing 32D cells. Similar results were observed using G1E-ER2 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Consequences of restoring individual early signaling pathways in c-Kit on proliferation. 32D cells expressing similar levels of the indicated c-Kit mutant receptors were cultured in the presence of M-CSF or IL-3 for 48 h or in the absence of a growth factor (GF) as a control for 48 h. Bars represent the mean thymidine incorporation (in counts per minute) in 32D cells in response to M-CSF or IL-3 stimulation of an independent experiment with four replicates (standard deviations indicated by the error bars). Similar results were observed in several other experiments. The asterisks indicate statistical significance. The value for the mutant c-Kit CHR in which the Src binding sites at positions 567 and 569 were restored (567/569) was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the value for the WT c-Kit CHR, and the values for c-Kit CHR mutants in which the Src binding sites at position 567 or position 569 were restored were significantly different (P < 0.05) from the values for the WT c-Kit CHR and the 567/569 mutant c-Kit CHR.

Restoration of the Src kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores survival and migration.

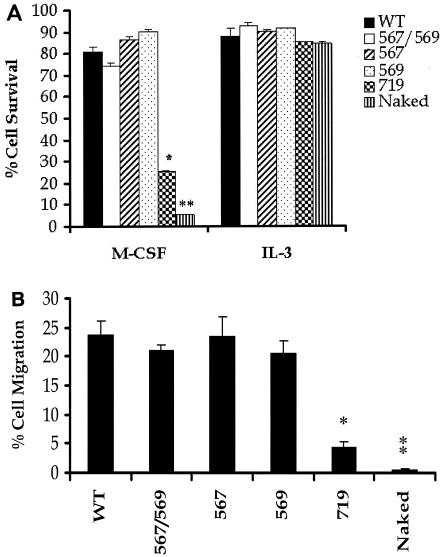

In addition to regulating proliferation, c-Kit also regulates the survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (2, 3, 25). To determine the roles of individual biochemical pathways in controlling c-Kit-mediated cell survival, 32D cells expressing various c-Kit mutants were subjected to an in vitro survival assay. As expected, stimulation of 32D cells expressing various c-Kit mutants with IL-3 resulted in a similar percentage of surviving cells (∼95%) (Fig. 4A), indicating that the overall well-being of 32D cells expressing various c-Kit mutants was similar. 32D cells expressing the Src-restored c-Kit mutants (positions 567/ and 569, 567, and 569) completely rescued the survival of these cells to WT levels in response to M-CSF stimulation (Fig. 4A). To our surprise, the c-Kit mutant in which the PI-3 kinase binding site was restored at position 719 demonstrated only a 30% rescue in survival compared to cells expressing WT c-Kit. More importantly, none of the other c-Kit mutants showed any effect on the survival of 32D cells in response to M-CSF stimulation (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Restoration of the Src kinase binding sites in the naked c-Kit receptor restores survival and migration. (A) Cells expressing various c-Kit mutants were cultured in the presence of IL-3 (positive control) or M-CSF for 24 h. Cells were harvested and stained with annexin V-PE to determine the percentage of surviving cells. Bars represent the percentage of cells surviving in the presence of M-CSF or IL-3 after 24 h of culture. The means ± standard deviations (error bars) of three independent experiments are shown. (B) Cells expressing various c-Kit mutants were subjected to an in vitro transwell migration assay as described in Materials and Methods. Bars represent the percentage of migrated cells in the presence of M-CSF over a 4-h culture period. All assays were performed in triplicate. In panels A and B, the means ± standard deviations (error bars) of three independent experiments are shown, and the asterisks indicate statistical significance. The value for the mutant c-Kit mutant in which the Src binding site at position 719 was restored was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the values for WT c-Kit CHR and c-Kit CHR mutants with the Src binding sites at positions 567 and 569 (567/569), position 567, and position 569 (*). The value for the naked c-Kit mutant was significantly different (P < 0.05) from the values for WT c-Kit CHR and c-Kit CHR mutants with the Src binding sites at positions 567 and 569 (567/569), position 567, position 569, and position 719 (**).

Previous studies have demonstrated a role for c-Kit in regulating chemotaxis or migration (2, 3, 25). To examine the role of c-Kit-induced early signaling pathways that regulate chemotaxis, we performed a 4-h transwell chemotaxis assay. Consistent with a dominant role for the Src kinase pathway in controlling proliferation and survival in response to c-Kit activation, M-CSF-induced migration was also rescued to WT levels in 32D cells expressing the Src-restored c-Kit mutant receptors (Fig. 4B). To our surprise, and in contrast to the previously described dominant role for the PI-3 kinase pathway in regulating chemotaxis in nonhematopoietic cells via the PDGFR, c-Kit-induced chemotaxis via the PI-3 kinase-restored receptor showed only a minor rescue in chemotaxis (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, and consistent with a lack of involvement of other biochemical pathways in regulating growth and survival in response to M-CSF stimulation, restoration of phenylalanine residues to tyrosines in c-Kit at position 702, 728, or 745 or 934 did not affect migration (data not shown). Collectively, these results demonstrate that activation of the Src kinase pathway alone is sufficient to partially restore proliferation and completely restore survival and migration in response to c-Kit activation in 32D cells. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that activation of the PI-3 kinase pathway via the binding of the p85α subunit of PI-3 kinase to the c-Kit receptor is not sufficient to rescue proliferation, survival, or migration in response to receptor activation. Surprisingly, other signaling pathways that are known to be activated in response to c-Kit stimulation, including Grb2, Grb7, and PLC-γ by themselves are incapable of sustaining the growth, survival, or migration of 32D cells.

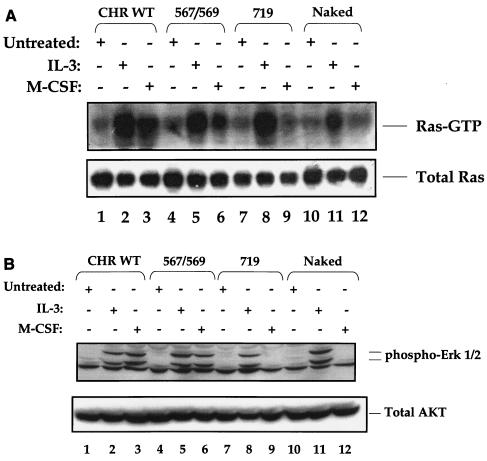

Restoration of the Src but not the PI-3 kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway.

To determine the biochemical consequence(s) of restoring early acting signaling pathways to the naked c-Kit receptor and to correlate the functional rescue observed via these receptors with the activation of distal signaling molecules, we examined the activation of the Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk pathway in response to M-CSF-induced stimulation of various c-Kit mutants. As shown in Fig. 5A, stimulation of 32D cells expressing the WT c-Kit receptor resulted in robust activation of Ras as measured in a Ras-GTP pull-down assay (Fig. 5A, lane 3). Stimulation of the c-Kit receptor in which the Src binding sites were restored to the naked receptor also rescued Ras activation, although at levels slightly lower than those of the WT c-Kit receptor (Fig. 5A, lane 6). To our surprise, and in contrast to previous studies demonstrating Ras activation by a PI-3 kinase-dependent pathway (12, 20, 23, 33, 40, 46), the naked c-Kit receptor in which only the PI-3 kinase binding site was restored showed no effect on the activation of Ras-GTP in response to receptor stimulation (Fig. 5A, lane 9). As expected, the naked c-Kit receptor stripped of seven tyrosine residues also did not activate Ras GTP (Fig. 5A, lane 12), although Ras activity in response to IL-3 stimulation was observed in this mutant receptor (Fig. 5A, lane 11). Consistent with a lack of functional rescue (proliferation, survival, and/or migration) in 32D cells expressing F702Y, F728Y, F745Y, or F934Y mutants, stimulation of these cells with M-CSF had no apparent effect on the activation of Ras-GTP (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Restoration of the Src binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway. (A) 32D cells expressing the indicated c-Kit mutant receptors were growth factor starved (−) and stimulated with either IL-3 or M-CSF (+) and subjected to a Ras pull-down assay followed by Western blot analysis using an anti-Ras antibody as detailed in Materials and Methods. (B) Lysates from panel A were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-phospho-Erk1/2 antibody. The positions of phosphorylated Erk1/2 are indicated to the right of the blot. The bottom blots in panels A and B show the total protein in each lane.

We next examined the effect of rescue of Ras activation on the phosphorylation of its downstream target, Erk, by measuring the phosphorylation of Erk1 and Erk2 in response to M-CSF stimulation. Consistent with the ability of the WT c-Kit receptor and the Src add-back mutant c-Kit receptor (positions 567 and 569) to restore the activation of Ras, M-CSF stimulation of these receptors also induced a rescue in the phosphorylation of MAP kinase Erk1/2 to WT levels (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 6). c-Kit mutants in which the sites at positions 567 and 569 were restored individually also restored the phosphorylation of Erk1/2 to levels similar to those observed with the 567/569 add-back c-Kit receptor (positions 567 and 569) (data not shown). Consistent with the absence of ligand-induced Ras activation in the restored PI-3 kinase and in the naked c-Kit receptor, no phosphorylation of either Erk1 or Erk2 was observed in response to M-CSF stimulation of these receptors (Fig. 5B, lanes 9 and 12). Collectively, these results demonstrate that restoring the activation of the Src kinase pathway to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of the Ras/Raf/Erk MAP kinase pathway. However, restoring the PI-3 kinase pathway does not induce the activation of either Ras or its downstream target, Erk.

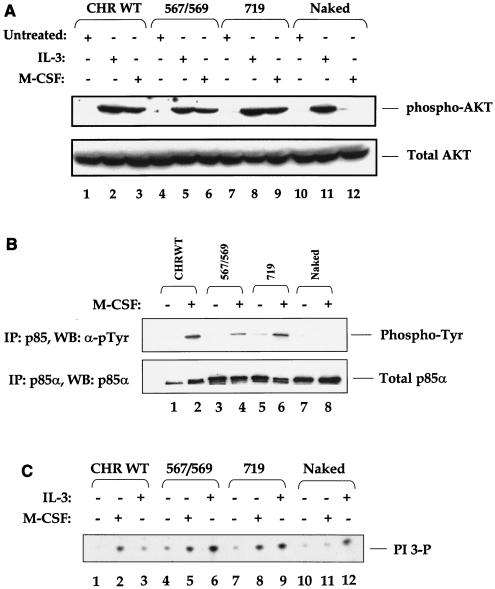

Restoration of the Src and PI-3 kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of PI-3 kinase and AKT.

Previous studies have implicated PI-3 kinase in regulating the survival of cells via the activation of AKT (11). However, restoring the PI-3 kinase binding site to the naked c-Kit receptor only partially rescued survival in our studies (Fig. 4A). To determine whether this finding was in part due to defective AKT activation, we performed Western blot analysis on M-CSF-stimulated cells using an anti-phospho-AKT antibody (Fig. 6A). Restoration of the PI-3 kinase pathway to the naked c-Kit receptor restored the activation of AKT to levels similar to those observed in response to M-CSF stimulation in cells expressing WT c-Kit (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 9). To our surprise, restoring the Src binding sites (positions 567 and 569) in the naked c-Kit receptor also restored AKT activation (Fig. 6A, lane 6). The rescue in the activation of AKT in the 567 and 569 individually restored add-back c-Kit mutant receptors was similar to that observed in the 567/569 add-back c-Kit receptor (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that restoring the Src or PI-3 kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor is sufficient to restore the activation of AKT. However, restoration of AKT activation alone is not sufficient to rescue the survival of 32D cells in response to receptor activation.

FIG. 6.

Restoration of the Src and PI-3 kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of PI-3 kinase and AKT. (A) Cells were treated as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Equal amounts of lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-phospho-AKT antibody. The position of phosphorylated AKT (Ser 473) is indicated to the right of the blot. (B) 32D cells treated as described above were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-p85α antibody followed by Western blot (WB) analysis with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody (α-pTyr) or an anti-p85α antibody. The positions of phosphorylated and total p85α in each lane are indicated to the right of the blots. (C) Lysates from panel A were subjected to a PI-3 kinase lipid assay. The position of PI-3 phosphate (PI-3P) is indicated to the right of the blot. The figure shows the results from one of four representative experiments.

Next, we examined the intracellular mechanism(s) by which restoration of the Src binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor might rescue the activation of AKT. We hypothesized that AKT activation in the Src add-back c-Kit mutant receptors might be a consequence of a direct physical association between Src family members and the p85α subunit of PI-3 kinase. This interaction may then induce the phosphorylation of p85α, resulting in the activation of PI-3 kinase and its downstream target, AKT. To test this hypothesis, we stimulated 32D cells expressing the WT, Src add-back, or PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit receptors with M-CSF and examined the phosphorylation of p85α and associated lipid phosphorylation activity. As expected, stimulation of PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutant receptor with M-CSF resulted in phosphorylation of p85α to WT levels (Fig. 6B, lane 6), which correlated with a complete rescue in the PI-3 kinase lipid phosphorylation activity (Fig. 6C, lane 8). More importantly, and consistent with our hypothesis, activation of 32D cells expressing the Src add-back c-Kit receptor also resulted in the phosphorylation of p85α and activation of PI-3 kinase to levels similar to those observed with the WT and PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutants (Fig. 6B and C, lanes 4 and 5, respectively). Taken together, these results suggest a mechanism by which restoring the Src kinase binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the phosphorylation of p85α and activation of PI-3 kinase and its downstream target (AKT) in response to c-Kit activation.

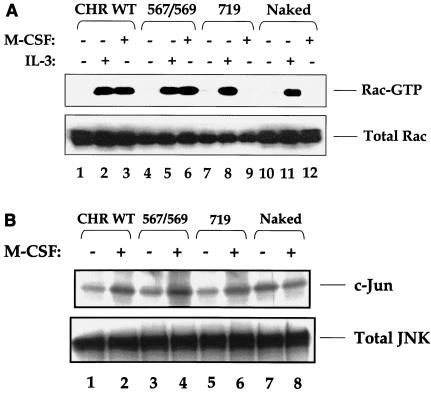

Restoration of the Src binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of Rac and JNK.

To determine the biochemical basis for the rescue in chemotaxis via the Src add-back mutant c-Kit receptors, we examined the activation of Rho family GTPase, Rac. Rac has been shown to regulate actin-based cytoskeletal functions in nonhematopoietic cells, including chemotaxis of fibroblasts in response to PDGF stimulation (17). Furthermore, Rac can be activated in a PI-3 kinase- and Src kinase-dependent fashion (5, 29, 34). To determine the mechanism of Rac activation via c-Kit and to examine whether the rescue of chemotaxis via the Src add-back mutant was in part due to the activation of Rac, 32D cells expressing the WT, Src add-back, or PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutant receptors were stimulated with M-CSF, and Rac-GTP levels were measured. Figure 7A demonstrates a complete rescue in the activation of Rac-GTP in 32D cells expressing the Src add-back receptor (lane 6), but not in the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit receptor (lane 9). Consistent with the activation of Rac, stimulation of 32D cells expressing the Src add-back receptor also resulted in the rescue of JNK kinase activity (Fig. 7B, lane 4). To our surprise, and in contrast to a previously identified role for PI-3 kinase in Rac activation, stimulation of 32D cells expressing the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit receptor did not induce the activation of Rac or JNK in response to M-CSF (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 9 and 6, respectively).

FIG. 7.

Restoration of the Src binding sites in the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of Rac and JNK. (A) Cell lysates derived from the treatment described for Fig. 5 were analyzed for Rac activation by incubating the lysates with PAK-1 p21-activated kinase binding domain-agarose (binds activated Rac), and bound protein fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-Rac antibody. The position of Rac-GTP (active Rac) is indicated to the right of the blot. (B) Cell lysates derived as described for Fig. 5 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-JNK antibody followed by an in vitro kinase assay using c-Jun as a substrate. The bottom blots in panels A and B show total Rac and JNK protein in each lane. The figure shows the results from one of four representative experiments.

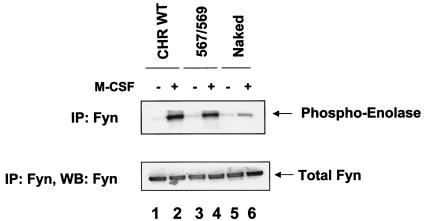

To further confirm that restoring the Src binding sites to the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of Src family kinases, Src add-back c-Kit mutants were stimulated with M-CSF and analyzed for the activation of Fyn Src family kinase. Figure 8 demonstrates a complete rescue in the activation of Fyn SFK in the Src add-back c-Kit mutants. Taken together, these results demonstrate that c-Kit-induced proliferation, survival, and migration require the activation of the Ras/Raf/Mek/Erk and PI-3 kinase/AKT pathways, as well as the activation of small GTPase Rac. Importantly, restoring the Src family kinase binding sites in an otherwise “dead” c-Kit receptor is sufficient to rescue all of the above cellular functions as well as the activation of essential downstream signaling proteins that have been implicated in controlling these cellular functions.

FIG. 8.

Restoration of the Src binding sites in the naked c-Kit receptor restores the activation of Fyn Src kinase. Cells treated as described above were lysed, and equal amounts of protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-Fyn antibody, followed by an in vitro kinase assay using acid-treated enolase as a substrate. The position of phospho-enolase is indicated to the right of the top blot. Phospho-enolase was detected by autoradiogram. The bottom blot shows the total immunoprecipitated Fyn in each lane. The figure shows the results from one of two representative experiments. WB, Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have examined c-Kit RTK function in hematopoietic cells and have addressed the individual contribution of specific signaling pathways by restoring each of the pathways individually to a naked c-Kit receptor. We demonstrate that the naked c-Kit receptor failed to sustain cellular functions and activation of biochemical pathways induced via c-Kit, including proliferation, survival, and migration. Proliferation measured by a thymidine incorporation assay was partially restored when the SFK binding sites (positions 567 and 569) were restored in the naked c-Kit receptor, although survival and migration were restored to WT levels under these conditions. To our surprise, restoring any of the other binding sites for SH2-containing molecules to the naked c-Kit receptor, including the binding sites for PI-3 kinase (position 719), PLC-γ (position 728), Grb7 (position 934), or Grb2 (position 702) had no effect on proliferation, survival, or migration, with the exception of a minor correction in the survival and migration of cells expressing the PI-3 kinase-restored c-Kit receptor.

Our findings utilizing the c-Kit receptor are in contrast to previously published results reported by Valius and Kazlauskas utilizing the PDGF add-back receptors (42). In those studies, restoring the PI-3 kinase or the PLC-γ pathway in the naked PDGFR restored the mitogenic signal to WT levels in the presence of saturating amounts of PDGF. Furthermore, restoration of the PLC-γ or PI-3 kinase binding sites to the naked PDGFR also restored ligand-induced Ras activation (42). Utilizing a PDGFR-related family member, c-Kit, we demonstrate that restoring the association of PI-3 kinase or PLC-γ has no apparent effect on the activation of Ras or its downstream target Erk in the presence of saturating levels of M-CSF. Our results utilizing saturating levels of M-CSF demonstrate that stimulation of cells expressing the Src- or PI-3 kinase-restored c-Kit receptor rescue AKT activation to the same extent, although the Src-restored c-Kit receptor also restores the activation of additional distal signaling molecules, such as Ras and Rac. These results demonstrate that although c-Kit and PDGFR belong to the same subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases, each utilizes distinct signaling mechanisms for regulating functional and biochemical outcomes upon receptor activation. Furthermore, these results suggest that although c-Kit receptor activation of downstream signaling molecules is modestly redundant, activation of distinct immediate-early molecules contributes unequally to the rescue of cellular functions and stimulation of distal signaling pathways.

Work from several laboratories, including our own, has demonstrated a modest, but significant role for the PI-3 kinase binding site (position 719) in triggering mitogenesis and survival as well as chemotaxis in response to receptor activation (35, 37, 39). In two separate studies, utilizing a knock-in strategy, a point mutation at residue 719 in the setting of the whole organism caused only minor defects in the hematopoietic lineages most affected by c-Kit mutations (1, 21). An even more minor role for PLC-γ (position 7285), Grb2 (position 702), Grb7 (position 934), or tyrosine 745 in triggering chemotaxis in response to c-Kit activation has been suggested (41). Consistent with these observations, when assayed in the context of the naked c-Kit receptor, none of the above SH2-containing proteins restored DNA synthesis, with the exception of a minor rescue in survival and chemotaxis via the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit receptor. Collectively, the results obtained from studies utilizing single point mutants of c-Kit causing impaired binding of PLC-γ (position 728), Grb2 (position 702), Grb7 (position 934), and tyrosine 745 together with results of our add-back approach strongly suggest that none of these SH2-containing proteins plays a critical role in regulating cellular DNA synthesis, chemotaxis, or migration via c-Kit activation in the context of cells examined in this study.

Our results demonstrating the activation of PI-3 kinase by the c-Kit receptor by direct recruitment of PI-3 kinase to the receptor or indirectly by a Src-dependent mechanism are intriguing. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that c-Kit can activate PI-3 kinase by a separate mechanism independent of direct PI-3 kinase-receptor interactions observed previously (35). Our results suggest that this may be mediated in part by the phosphorylation of the p85α subunit of PI-3 kinase by Src family kinases. To this end, Src family members have been previously shown to directly bind p85α and activate PI-3 kinase (31). Additionally, activated Src family kinases can phosphorylate docking or scaffolding proteins, which contain binding sites for the SH2 domain of p85α. Examples of docking proteins implicated in RTK signaling include Gab1/2 and c-Cbl. Interestingly, deficiency of Gab2 in mast cells results in reduced proliferation and activation of Erk and Akt in response to stem cell factor stimulation (30). On the basis of these observations, it is reasonable to speculate that Gab2 might play a significant role in regulating PI-3 kinase activation via the Src family kinases in the Src add-back c-Kit mutant receptors employed in our studies. Taken together, our results provide new insight into alternate mechanisms of PI-3 kinase/Akt activation via c-Kit in the absence of receptor binding sites for the p85α subunit of PI-3 kinase.

Our studies utilizing the c-Kit add-back receptor approach demonstrate that Erk activation by Ras does not require PI-3 kinase, since PI-3 kinase c-Kit add-back mutants are unable to restore the activation of Erk. These data are in contrast to previous studies demonstrating a role for PI-3 kinase in Ras-induced Erk activation via the M-CSFR (22). The apparent differences are likely due to differences in the two receptor tyrosine kinases. Previous studies suggested an involvement of Shc, Grb2, Gab1/2, and SHP-2 in the activation of Ras and Erk via RTKs, including via c-Kit (18, 24, 27). Whether Grb2 or Gab2 is involved in the rescue of Ras/MAP kinase activation in our Src add-back c-Kit mutants is currently being investigated.

Previous studies have shown a role for the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav in regulating the activity of Rho family members, including Rac (6, 15, 16). Phospholipid products of PI-3 kinase as well as the activation of Src family kinases have been shown to regulate the activation of Vav (6, 15, 16, 29). Src family kinases are thought to regulate the activation of Vav by tyrosine phosphorylation of the Dbl homology domain (6, 15). In contrast, the phospholipid products generated by PI-3 kinase activate Vav via the pleckstrin homology domain (16, 29). Our results utilizing the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutant clearly demonstrate that restoring the activation of PI-3 kinase to c-Kit alone is not sufficient to restore the activation of Rac. However, restoring the activation of Src family kinases completely restores Rac activation. It is conceivable that this is due in part to inadequate activation of Vav by the phospholipid products generated by the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutant receptor. The extent to which the PI-3 kinase add-back c-Kit mutant receptor activates Vav compared to the Src add-back c-Kit mutants will shed light into the mechanism on Rac activation in response to c-Kit receptor activation.

Our finding that PI-3 kinase induced AKT activation via the PI-3 kinase-restored c-Kit mutant is not sufficient to rescue survival, suggests that Ras and/or Rac activation via the Src-restored c-Kit mutant is essential for c-Kit-mediated survival of hematopoietic cells. Whether both Ras and Rac are required for this process is currently being investigated.

In summary, our results utilizing the add-back approach provide new insight into c-Kit signaling in hematopoietic cells and raise a number of provocative paradoxes. Since the Src family members partially rescue DNA synthesis and completely rescue cellular survival and chemotaxis in the naked c-Kit receptor, as well as activate a significant number of distal signaling molecules, one must question the role of the remaining tyrosine residues on the c-Kit receptor. Although the cytoplasmic domain of c-Kit consists of 22 tyrosine residues, including 12 in the two kinase domains, our results indicate that loss of only seven tyrosine residues, including the ones in the region next to the membrane, kinase insert, and the tail of c-Kit, is sufficient to completely eliminate all of the cellular functions and signaling activity associated with the WT c-Kit receptor. Whether these additional tyrosine residues bind novel SH2 domain-containing proteins and whether restoration of a given tyrosine phosphorylation site to the naked c-Kit receptor allows the receptor to couple with additional SH2-containing proteins remains to be determined. Importantly, our results utilizing a functionally and biochemically incompetent naked c-Kit mutant receptor suggest that additional proteins that might be able to couple to this receptor are not sufficient to transmit a positive mitogenic, survival, or chemotactic signal upon receptor activation. However, it is conceivable that these additional tyrosine residues in c-Kit may be required for a very specific function to amplify a core signal induced primarily by the Src kinase pathway. Whether these tyrosines contribute to critical or subtle functions via c-Kit in vivo is currently being investigated using a knock-in strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory and colleagues for useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blume-Jensen, P., G. Jiang, R. Hyman, K. F. Lee, S. O'Gorman, and T. Hunter. 2000. Kit/stem cell factor receptor-induced activation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase is essential for male fertility. Nat. Genet. 24:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boissan, M., F. Feger, J. J. Guillosson, and M. Arock. 2000. c-Kit and c-kit mutations in mastocytosis and other hematological diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:135-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broudy, V. C. 1997. Stem cell factor and hematopoiesis. Blood 90:1345-1364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter, C. L., B. C. Duckworth, K. R. Auger, B. Cohen, B. S. Schaffhausen, and L. C. Cantley. 1990. Purification and characterization of phosphoinositide 3-kinase from rat liver. J. Biol. Chem. 265:19704-19711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiariello, M., M. J. Marinissen, and J. S. Gutkind. 2001. Regulation of c-myc expression by PDGF through Rho GTPases. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:580-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo, P., K. E. Schuebel, A. A. Ostrom, J. S. Gutkind, and X. R. Bustelo. 1997. Phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of Rac-1 GDP/GTP exchange by the vav proto-oncogene product. Nature 385:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutler, R. L., L. Liu, J. E. Damen, and G. Krystal. 1993. Multiple cytokines induce the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and its association with Grb2 in hemopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268:21463-21465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeMali, K. A., and A. Kazlauskas. 1998. Activation of Src family members is not required for the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor to initiate mitogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2014-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duronio, V., M. J. Welham, S. Abraham, P. Dryden, and J. W. Schrader. 1992. p21ras activation via hemopoietin receptors and c-kit requires tyrosine kinase activity but not tyrosine phosphorylation of p21ras GTPase-activating protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1587-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fambrough, D., K. McClure, A. Kazlauskas, and E. S. Lander. 1999. Diverse signaling pathways activated by growth factor receptors induce broadly overlapping, rather than independent, sets of genes. Cell 97:727-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franke, T. F., D. R. Kaplan, L. C. Cantley, and A. Toker. 1997. Direct regulation of the Akt proto-oncogene product by phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate. Science 275:665-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost, J. A., H. Steen, P. Shapiro, T. Lewis, N. Ahn, P. E. Shaw, and M. H. Cobb. 1997. Cross-cascade activation of ERKs and ternary complex factors by Rho family proteins. EMBO J. 16:6426-6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gommerman, J. L., D. Sittaro, N. Z. Klebasz, D. A. Williams, and S. A. Berger. 2000. Differential stimulation of c-Kit mutants by membrane-bound and soluble steel factor correlates with leukemic potential. Blood 96:3734-3742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory, T., C. Yu, A. Ma, S. H. Orkin, G. A. Blobel, and M. J. Weiss. 1999. GATA-1 and erythropoietin cooperate to promote erythroid cell survival by regulating bcl-xL expression. Blood 94:87-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, J., B. Das, W. Wei, L. Van Aelst, R. D. Mosteller, R. Khosravi-Far, J. K. Westwick, C. J. Der, and D. Broek. 1997. Lck regulates Vav activation of members of the Rho family of GTPases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:1346-1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han, J., K. Luby-Phelps, B. Das, X. Shu, Y. Xia, R. D. Mosteller, U. M. Krishna, J. R. Falck, M. A. White, and D. Broek. 1998. Role of substrates and products of PI 3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science 279:558-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heldin, C. H., A. Ostman, and L. Ronnstrand. 1998. Signal transduction via platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1378:F79-F113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh, M., Y. Yoshida, K. Nishida, M. Narimatsu, M. Hibi, and T. Hirano. 2000. Role of Gab1 in heart, placenta, and skin development and growth factor- and cytokine-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3695-3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jahn, T., P. Seipel, S. Urschel, C. Peschel, and J. Duyster. 2002. Role for the adaptor protein Grb10 in the activation of Akt. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:979-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King, A. J., H. Sun, B. Diaz, D. Barnard, W. Miao, S. Bagrodia, and M. S. Marshall. 1998. The protein kinase Pak3 positively regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine 338. Nature 396:180-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kissel, H., I. Timokhina, M. P. Hardy, G. Rothschild, Y. Tajima, V. Soares, M. Angeles, S. R. Whitlow, K. Manova, and P. Besmer. 2000. Point mutation in kit receptor tyrosine kinase reveals essential roles for kit signaling in spermatogenesis and oogenesis without affecting other kit responses. EMBO J. 19:1312-1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, A. W., and D. J. States. 2000. Both src-dependent and -independent mechanisms mediate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulation of colony-stimulating factor 1-activated mitogen-activated protein kinases in myeloid progenitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6779-6798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Good, J. A., W. H. Ziegler, D. B. Parekh, D. R. Alessi, P. Cohen, and P. J. Parker. 1998. Protein kinase C isotypes controlled by phosphoinositide 3-kinase through the protein kinase PDK1. Science 281:2042-2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lennartsson, J., P. Blume-Jensen, M. Hermanson, E. Ponten, M. Carlberg, and L. Ronnstrand. 1999. Phosphorylation of Shc by Src family kinases is necessary for stem cell factor receptor/c-kit mediated activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and c-fos induction. Oncogene 18:5546-5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linnekin, D. 1999. Early signaling pathways activated by c-Kit in hematopoietic cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31:1053-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linnekin, D., C. S. DeBerry, and S. Mou. 1997. Lyn associates with the juxtamembrane region of c-Kit and is activated by stem cell factor in hematopoietic cell lines and normal progenitor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:27450-27455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lioubin, M. N., G. M. Myles, K. Carlberg, D. Bowtell, and L. R. Rohrschneider. 1994. Shc, Grb2, Sos1, and a 150-kilodalton tyrosine-phosphorylated protein form complexes with Fms in hematopoietic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:5682-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maddens, S., A. Charruyer, I. Plo, P. Dubreuil, S. Berger, B. Salles, G. Laurent, and J. P. Jaffrezou. 2002. Kit signaling inhibits the sphingomyelin-ceramide pathway through PLC gamma 1: implication in stem cell factor radioprotective effect. Blood 100:1294-1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nimnual, A. S., B. A. Yatsula, and D. Bar-Sagi. 1998. Coupling of Ras and Rac guanosine triphosphatases through the Ras exchanger Sos. Science 279:560-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishida, K., L. Wang, E. Morii, S. J. Park, M. Narimatsu, S. Itoh, S. Yamasaki, M. Fujishima, K. Ishihara, M. Hibi, Y. Kitamura, and T. Hirano. 2002. Requirement of Gab2 for mast cell development and KitL/c-Kit signaling. Blood 99:1866-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pleiman, C. M., W. M. Hertz, and J. C. Cambier. 1994. Activation of phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase by Src-family kinase SH3 binding to the p85 subunit. Science 263:1609-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattler, M., R. Salgia, G. Shrikhande, S. Verma, E. Pisick, K. V. Prasad, and J. D. Griffin. 1997. Steel factor induces tyrosine phosphorylation of CRKL and binding of CRKL to a complex containing c-kit, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and p120CBL. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10248-10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schonwasser, D. C., R. M. Marais, C. J. Marshall, and P. J. Parker. 1998. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:790-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scita, G., J. Nordstrom, R. Carbone, P. Tenca, G. Giardina, S. Gutkind, M. Bjarnegard, C. Betsholtz, and P. P. Di Fiore. 1999. EPS8 and E3B1 transduce signals from Ras to Rac. Nature 401:290-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serve, H., N. S. Yee, G. Stella, L. Sepp-Lorenzino, J. C. Tan, and P. Besmer. 1995. Differential roles of PI3-kinase and Kit tyrosine 821 in Kit receptor-mediated proliferation, survival and cell adhesion in mast cells. EMBO J. 14:473-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon, M. A. 2000. Receptor tyrosine kinases: specific outcomes from general signals. Cell 103:13-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan, B. L., L. Hong, V. Munugalavadla, and R. Kapur. 2003. Functional and biochemical consequences of abrogating the activation of multiple diverse early signaling pathways in Kit. Role for Src kinase pathway in Kit-induced cooperation with erythropoietin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11686-11695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thommes, K., J. Lennartsson, M. Carlberg, and L. Ronnstrand. 1999. Identification of Tyr-703 and Tyr-936 as the primary association sites for Grb2 and Grb7 in the c-Kit/stem cell factor receptor. Biochem. J. 341:211-216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Timokhina, I., H. Kissel, G. Stella, and P. Besmer. 1998. Kit signaling through PI 3-kinase and Src kinase pathways: an essential role for Rac1 and JNK activation in mast cell proliferation. EMBO J. 17:6250-6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toker, A., M. Meyer, K. K. Reddy, J. R. Falck, R. Aneja, S. Aneja, A. Parra, D. J. Burns, L. M. Ballas, and L. C. Cantley. 1994. Activation of protein kinase C family members by the novel polyphosphoinositides PtdIns-3,4-P2 and PtdIns-3,4,5-P3. J. Biol. Chem. 269:32358-32367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueda, S., M. Mizuki, H. Ikeda, T. Tsujimura, I. Matsumura, K. Nakano, H. Daino, Z. Honda Zi, J. Sonoyama, H. Shibayama, H. Sugahara, T. Machii, and Y. Kanakura. 2002. Critical roles of c-Kit tyrosine residues 567 and 719 in stem cell factor-induced chemotaxis: contribution of src family kinase and PI3-kinase on calcium mobilization and cell migration. Blood 99:3342-3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valius, M., and A. Kazlauskas. 1993. Phospholipase C-gamma 1 and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase are the downstream mediators of the PDGF receptor's mitogenic signal. Cell 73:321-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Geer, P., T. Hunter, and R. A. Lindberg. 1994. Receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and their signal transduction pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 10:251-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Dijk, T. B., E. van Den Akker, M. P. Amelsvoort, H. Mano, B. Lowenberg, and M. von Lindern. 2000. Stem cell factor induces phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-dependent Lyn/Tec/Dok-1 complex formation in hematopoietic cells. Blood 96:3406-3413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams, D. A., W. Tao, F. Yang, C. Kim, Y. Gu, P. Mansfield, J. E. Levine, B. Petryniak, C. W. Derrow, C. Harris, B. Jia, Y. Zheng, D. R. Ambruso, J. B. Lowe, S. J. Atkinson, M. C. Dinauer, and L. Boxer. 2000. Dominant negative mutation of the hematopoietic-specific Rho GTPase, Rac2, is associated with a human phagocyte immunodeficiency. Blood 96:1646-1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yart, A., M. Laffargue, P. Mayeux, S. Chretien, C. Peres, N. Tonks, S. Roche, B. Payrastre, H. Chap, and P. Raynal. 2001. A critical role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase upstream of Gab1 and SHP2 in the activation of ras and mitogen-activated protein kinases by epidermal growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8856-8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]