Abstract

The Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (HGP) syndrome is an extremely rare genetic condition characterized by an appearance of accelerated aging in children. The word progeria is derived from the Greek word progeros meaning ‘prematurely old’. It is caused by de novo dominant mutation in the LMNA gene (gene map locus 1q21.2) and characterized by growth retardation and accelerated degenerative changes of the skin, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems. The most common ocular manifestations are prominent eyes, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, and lagophthalmos. In the present case some additional ocular features such as horizontal narrowing of palpebral fissure, superior sulcus deformity, upper lid retraction, upper lid lag in down gaze, poor pupillary dilatation, were noted. In this case report, a 15-year-old Indian boy with some additional ocular manifestations of the HGP syndrome is described.

Keywords: Hutchinson-Guilford progeria syndrome, ocular manifestations, premature aging syndrome, progeria

The Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (HGP) syndrome is an extremely rare, genetic condition characterized by an appearance of accelerated aging in children.[1] The word progeria is derived from the Greek word progeros meaning ‘prematurely old’.[2] It is characterized by growth retardation and accelerated degenerative changes of the skin, musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems.[2] The most common ocular manifestations are prominent eyes, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, and lagophthalmos. In the present case some additional ocular features such as horizontal narrowing of palpebral fissure, superior sulcus deformity, upper lid retraction, upper lid lag in down gaze, poor pupillary dilatation, were noted. In this case report, a 15-year-old Indian boy with some additional ocular manifestations of the HGP syndrome is described.

Case Report

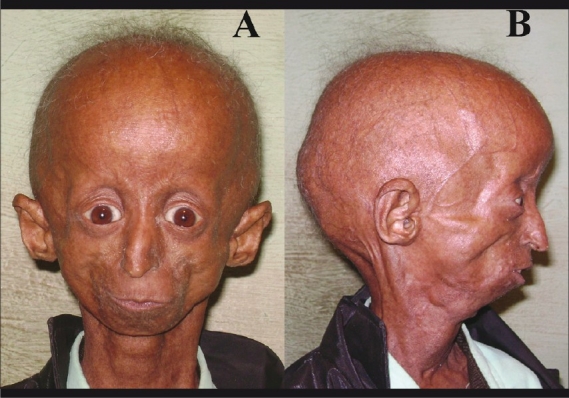

A 15-year-old Indian boy was referred to us for ophthalmic evaluation. The antenatal period was uneventful and delivery was normal at 41 weeks of gestation. His parents were healthy and nonconsanguineous and he has two unaffected older siblings. Detailed records pertaining to birth history and infancy were not available for review. General physical examination at age 15 years showed: height 113 cm (<3rd percentile), weight 10 kg (<3rd percentile), and head circumference 48 cm. Blood pressure was 134/90 mm of Hg. He was apparently well up to the age of 18 months, later he developed failure to thrive, loss of hair, prominent eyes and joints, and senile appearance. Systemic examination revealed craniofacial disproportion, mandibular and maxillary hypoplasia, prominent scalp veins, ‘plucked bird appearance’, thin lips, irregular and carious teeth, dental crowding, beaked nose, protruding ears with absent ear lobes, pyriform thorax, thin limbs, prominent and stiff joints, wide-based gait and shuffling, thin and high-pitch voice, incomplete sexual maturation, generalized alopecia, absence of subcutaneous fat, thin and wrinkled ‘sclerodermatous’ skin, prominent superficial veins, and nail dystrophy [Figs. 1–3]. A cardiac evaluation revealed left ventricular hypertrophy. Color Doppler study of abdomen showed right renal artery stenosis. X-ray survey of the skeletal system showed radiolucent terminal phalanges; coxa vulga, enlarged metaphysis of long bones, short dystrophic clavicle and osteoporosis [Fig. 4A and B]. His intelligent quotient (IQ) was normal. His best corrected visual acuity was 20/20, N6 in both eyes (BE) with -1.25 cylinders at 161° in right eye (RE) and -0.50 cylinders at 41° in left eye (LE).

Figure 1.

External photograph of a 15-year-old Hutchinson-Guilford progeria male patient (A) showing disproportionately small face in comparison to the head, micrognathia, prominent eyes, both upper eyelids’ retraction, beaked nose, thin lips. (B) Prominent scalp veins, alopecia with grey and sparse hairs, and protruding ears with absent earlobe

Figure 3.

Prominent joints of hand (red arrow: metacarpophalangeal joints, blue arrow: interphalangeal joints) with loss of subcutaneous fat, nail dystrophy and sclerodematous skin

Figure 4.

(A) X-ray hand showing radiolucent terminal phalanges (white arrow) and osteoporotic changes (black arrow). (B) X-ray shoulder joint showing dystrophic and short clavicle (white arrow)

Figure 2.

(A) Upper jaw dental crowding and dental caries (B) Lower jaw dental crowding and dental caries

External ocular examination showed excessive wrinkling of forehead, superior sulcus deformity, inner canthal distance 20 mm, outer canthal distance 58 mm, inter-pupillary distance 40 mm, vertical palpebral fissure 12 mm, horizontal palpebral fissure 20 mm, lagophthalmos 2 mm, upper eyelid retraction 2.5 mm, upper lid lag in down gaze 5 mm, in BE, nearly total loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, a few present eyelashes and eyebrows showed poliosis [Fig. 5A and B]. Slit-lamp examination revealed normal anterior segment. Intraocular pressure by applanation tonometry was 12 mm of Hg in BE. Hertels exophthalmometry did not reveal proptosis. Extraocular movements, evaluation for squint, and lacrimal system were unremarkable. Gonioscopy and A-Scan biometry were unremarkable. Both pupils showed poor dilatation with tropicamide 0.8% and phenylephrine 5%. Fundus examination of BE showed tessellations, rest of the fundus picture was normal. Urine examination was positive for hyluronic acid. Thus, in view of the characteristic clinical presentation, imaging studies, and urine analysis, the child was diagnosed to have HGP syndrome. The patient died of acute myocardial infarction at the age of 16.5 years.

Figure 5.

(A) Both upper lids lag in down gaze, superior sulcus deformity, loss of eyelashes and eyebrows. (B) Lagophthalmos

Discussion

The HGP syndrome is an extremely rare, fatal, genetic disorder of childhood with striking features resembling premature aging. It is caused by de novo dominant mutation in the LMNA gene.[3] The Caucasians represent 97% of reported cases.[2] The HGP syndrome has a slight male predilection; the male-to-female ratio is 1.5:1.[1] Currently, more than 142 patients with the HGP syndrome have been reported worldwide.[4] The incidence of the HGP syndrome has been estimated at 1 in 4-8 million live births.[2,4] The clinical diagnosis of the HGP syndrome is based on recognition of characteristic features and exclusion of other progeroid syndromes.[5] Children with progeria usually have a normal physical appearance in early infancy.[1,2] At approximately one to two years of age, affected children develop severe growth retardation, resulting in short stature, low weight and delayed anterior fontanel closure. These children develop a distinctive facial appearance characterized by a disproportionately small face in comparison to the head, micrognathia, delayed dentitions, dental malformation and crowding, beaked nose, prominent eyes, nasolabial circumoral cyanosis and loss of scalp hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Other characteristic features include generalized atherosclerosis, cardiovascular diseases and stroke, hip dislocations, prominent scalp veins, lipodystrophy, dystrophy of nails, joint stiffness, skeletal defects, and/or other abnormalities.[1,2] The most common reported ocular features are prominent eyes, loss of eyebrows and eyelashes, and lagophthalmos.[1,4] Other rare ocular manifestations of the HGP syndrome are bands of skin running from the upper lid to the cornea, senile ectropion, ptosis with Marcus-jaw-winking phenomenon, dry-eye syndrome, corneal dryness, keratopathy, iridocorneal adhesions, corneal opacities, corneal clouding, cataract, strabismus, irregular nystagmoid movements, myopia, hyperopia, retinal arteriolar narrowing and tortuosity, and retinal angiosclerosis.[4,6–8] Many of these findings are based on individual case reports and are absent in the present case.[4,6,7] The ophthalmic anthropometric measurements such as horizontal palpebral fissure length, interpupillary distance, inner canthal distance, outer canthal distance in our patient are less than aged-matched normal Indian values. It is probably due to underdeveloped facial skeleton.[4] Eyelid retractions, lagophthalmos, lid lag in down gaze, are due to inelastic and taut skin. Poor pupillary dilatation may be due to ischemic changes in the iris muscles secondary to microvascular insufficiency induced by atherosclerosis, however, visible atrophic changes were absent on slit-lamp examination in our patient.[9] In the HGP syndrome eyes looks prominent (pseudoproptosis) probably due to lid retraction, although there is no true proptosis.[4] Superior sulcus deformity is due to lipodystrophy of the orbital fat. Interestingly, patients with HGPS do not develop other ocular features associated with aging, such as presbiopia, arcus senilis or age-related macular degeneration. The exact mechanism of sparing these ocular signs is still unknown. The HGP syndrome should be differentiated from other progeroid syndromes such as Werner's syndrome (adult progeria), Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch syndrome (neonatal progeria), Hallermann-Streiff syndrome, mandibuloacral dysplasia, Cockayne's syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, metageria and acrogeria.[1,2,10] The average life expectancy is 13 years, with an age range of 7-27 years.[2] The most common cause of death is myocardial infarction or congestive cardiac failure, secondary to widespread atherosclerosis.[2] At present no prophylaxis or treatment has been proved to be effective. We performed a Medline search with the key words “Progeria”, “Hutchinson-Guilford progeria syndrome”, “Ocular manifestations/ signs/features/ findings”, “Ophthalmic manifestations/signs/features/findings”, “eye”, “Premature ageing syndrome” and various combinations thereof. All cross-references in citing literature were included in our search and referenced. To the best of our knowledge, lid retraction, lid lag in down gaze, superior sulcus deformity and poor pupillary dilatation have not been reported previously in the HGP syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the family of the patient for their cooperation and for consenting to the publication of the photographs.

References

- 1.Sarkar PK, Shinton RA. Hutchinson-Guilford progeria syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:312–7. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.907.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stables GI, Morley WN. Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome. J R Soc Med. 1994;87:243–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennekam RC. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: Review of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:2603–24. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown TW. Progeria. In: Kliegman RM, Bohrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 636–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iordănescu C, Denislam D, Avram E, Chiru A, Busuioc M, Cioablă D. Ocular manifestations in progeria. Oftalmologia. 1995;39:56–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhakoo ON, Garg SK, Sehgal VN. Progeria with unusual ocular manifestations: Report of a case with a review of the literature. Indian Pediatr. 1965;2:164–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merideth MA, Gordon LB, Clauss S, Sachdev V, Smith AC, Perry MB, et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:592–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon LB, McCarten KM, Giobbie-Hurder A, Machan JT, Campbell SE, Berns SD, et al. Disease progression in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: Impact on growth and development. Pediatrics. 2007;120:824–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyer CA, Sinclair AJ. The premature ageing syndromes: Insights into the ageing process. Age Ageing. 1998;27:73–80. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]