Abstract

Background:

Perceived body image is an important potential predictor of nutritional status. Body image misconception during adolescence is unexplored field in Indian girls.

Objectives:

To study the consciousness of adolescent girls about their body image.

Materials and Methods:

This multistage observational study was conducted on 586 adolescent girls of age 10–19 years in Lucknow district (151 from rural, 150 from slum, and 286 from urban area) of Uttar Pradesh, India. Information on desired and actual body size was collected with the help of predesigned questionnaire.

Results:

20.5% of studied girls show aspiration to become thin, who already perceived their body image as too thin. 73.4% adolescent girls were satisfied with their body image, while 26.6% were dissatisfied. The dissatisfaction was higher among girls of urban (30.2%) and slum (40.0%) areas in comparison to rural (22.5%) area. Percentage of satisfied girls was less in the 13–15 years (69.9%) age groups in comparison to 10–12 years (76.5%) and 16–19 years (76.4%). Among girls satisfied with their body image, 32.8% girls were found underweight, and 38.4% were stunted. Underweight girls (42.1%) and stunted girls (64.9%) were higher in number within satisfied girls of slum area. Among all of these adolescent girls, 32.8% of girls had overestimated their weight, while only 4.9% of girls had underestimated their weight.

Conclusions:

This study concludes that desire to become thin is higher in adolescent girls, even in those who already perceived their body image as too thin.

Keywords: Adolescence, body image satisfaction, perceived body image, stunting, underweight

Introduction

Adolescence, intermediary phase from childhood to adulthood, is a delicate phase of life. It is estimated that there are about 69.7 million adolescent girls representing about 7.0% of the entire world's population.(1) Unique changes may occur during this period and adult patterns are established (WHO). The never-ending sequence of physical and psychological adaptations of adolescents has a remarkable influence on the social and behavioral aspects of their lives.(2,3) The standardized model of beauty in our society that prefers and emphasizes just particular physical aspects such as slimness and thinness influences adolescents’ beliefs of physical growth.(4) The lack of connection between the real and the ideal perception of their own body (body dissatisfaction) and the firm willingness to modify their body and shape so as to standardize them to the social concept of thinness (drive for thinness) are some of the main reasons responsible for the determined and constant adolescents’ drive to follow such ideal standards.(5–9)

Previous studies suggest that physical appearance and body image may influence perceived health. Adolescence is a period of increased awareness of bodily cues and self-reflection, including evaluation of body and appearance. Body dissatisfaction, negative body image, concern with body size, and shape represent attitudinal aspects of body image.(10) The concept of body image has been defined in different terms, according to scientific discipline. Body image is also often discussed without a definition or used interchangeably with other constructs.(11) In a longitudinal study, gender differences in body dissatisfaction emerged between 13 and 15 years of age and were maintained at 18 years. Throughout this period, girls increased and boys decreased body dissatisfaction.(12) According to one previous study 79% boys and 44% girls were satisfied with their weight.(10)

Age old gender distinction is a hard truth of Indian society. Beside it there are many differences in the current descriptions of adolescent's in India. The variations arise from factors such as urban, rural and slum or other marginalized residence, ethnicity, and socioeconomic levels of the family. India has undergone rapid urbanization over the past 60 years, yet more than two-third of the population live in rural areas. As per the 2001 Census, 72% and 28% of the Indian population was living in the rural and urban areas, respectively.(13) A considerable proportion of the population in most Indian cities lives in slum areas at present. The UN defined slums as communities characterized by insecure residential status, poor structural quality of housing, overcrowding, and inadequate access to safe water, sanitation, and other infrastructure.(14)

According to the 2001 Census, 42.6 million people lived in slums in 8.2 million households and 640 towns spread across 26 states and Union Territories in India. The slum estimates did not include towns below 50,000 population, as well as a few towns and cities with a population of 50,000 or more where local bodies did not recognize any slum area (136 towns in all, including such large cities as Lucknow) and a few northeastern states that did not have any urban centre with 50,000 or more population or that did not have any slum act.(15) In reality, people residing in legally undefined and unrecognized slums are facing even most terrible living conditions. They do not have access to even basic civic facilities, otherwise provided by government in legally defined slums.

Beside rapid economic growth of country, growing slum population in Indian cities is seen a signal of deterioration of living situations and escalating poverty in cities in India. The greater than ever concentration of population in slums and urban poverty have brought out a strong concern in urban health conditions in broad and the health of slum dwellers and the urban poor in particular.

The picture of rural adolescents is different; the disparity between boys and girls is even greater among them. Less emphasis on formal education makes boys and girls participate in adult activities at home and outside at an early age. The routine of a preadolescent/adolescent rural girl is demanding-cleaning the house, cooking, washing, fetching water, and bathing younger siblings.

Lifestyle of urban adolescents from upper socioeconomic status (SES) is also quite different from that of the middle-class and lower-class adolescents. Former have access to private, good quality education, and are influenced by western ways of life style through travel and exposure; their preferences are very close to the western counter parts. On the surface there does not appear to be any gender discrimination in the families of these adolescents but covertly they do exist. Pursuing educational endeavors is encouraged both in the upper and middle urban classes.

It is unfortunate that body misconception and body dissatisfaction, two very important potential causative factors of bad nutritional status of adolescent girls, have not been adequately investigated in India. No study has been conducted on body dissatisfaction and its consequences in adolescent girls belonging to Indian community. The present study on adolescent girls of Lucknow district was conducted to assess the degree of dissatisfaction and misconception of their body in three diverse and different strata of this population and to find out its association with stunting and thinness, two important outcomes of poor nutritional status.

Materials and Methods

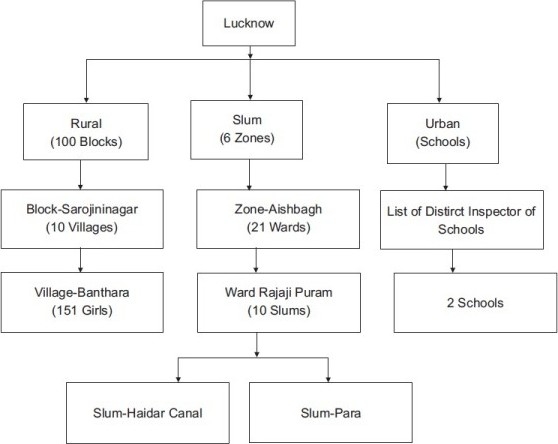

The observational study was conducted in Lucknow District of Uttar Pradesh. A total of 586 (151 from rural, 150 from slum, and 286 from urban area) adolescent girls of age 10–19 years were selected for this study. Steps involved in the selection of study subjects are given in the following flowchart [Flowchart 1].

Flowchart 1.

Selection protocol for subjects

Uttar Pradesh is the most populated state of India having population of more than 166 millions (male 87,466,301 female 78,586,558).(13) Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, has population of 3.6 million. It has got all the socioeconomic strata of rural, urban, and slum population. The majority of Lucknow's population comprises of people from Central and Eastern Uttar Pradesh and other adjoining districts. However, being administrative and political capital, people of other cities and states have also settled in large numbers. Hindus comprise about 77% and Muslims about 20%. There are also small groups of Sikhs, Jains, Christians, and Buddhists. More than half million (5.2 lakhs), i.e., 14.4% of its population is residing in the slums (Urban Reproductive and Child Health Programme (RCH- 2000). This population also contains a large number of migrated people from neighboring districts, states, and even some of them from other countries, i.e., Nepal and Bangladesh. It makes Lucknow, a fare representative of Indian adolescent girls’ population. Three different localities of Lucknow that were rural, slum, and urban area, selected for the study. The demographic data for each of the selected girl included information on age, number of family members, number of boys and girls in family, birth order of girl in the family, family income, family size, birth order, education, and occupation of parents. Information on desired and actual body size was collected with the help of predesigned questionnaire. Data were collected after taking informed consent from the subjects and their parents.

Measures

“Perceived Image” was measured by the following question: “what do you think about your body image?” with four responses “too fat,” “about right,” “perfect,” and “too thin.” Desired “body image” was asked by question: “what is your desired body image?” and the responses were “too thin,” “thin,” “neither too thin nor fat,” and “fatty.” No one had desired body image “fatty,” these categories were reduced to two in the analyses by combining “too thin” and “thin.” Therefore, two categories were remained: “thin” and “neither too thin nor fat.”

Anthropometry measurements

Height and weight were measured using anthropometric rod and weighing machine. Body mass index (BMI) was subsequently computed by formula weight (kg)/height (m2). The anthropometric nutritional status was assessed by “BMI for age” and “height for age” as per WHO standards. The subjects with BMI for age below 5th percentile were categorized as thin and those with “height for age” less then 3rd percentiles were considered to be stunted.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package of SPSS, version 11. Statistical measures such as frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and Chi-square test were implicated to describe and analysis of data.

Results

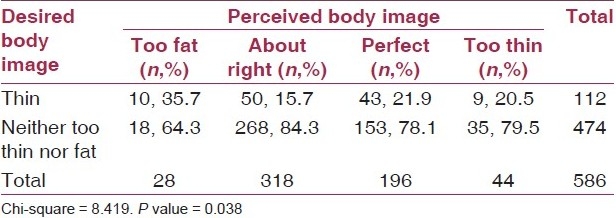

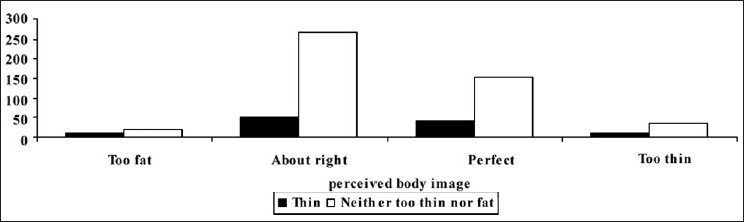

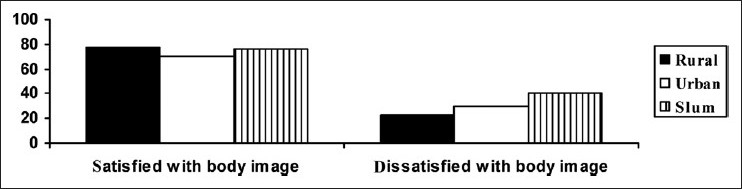

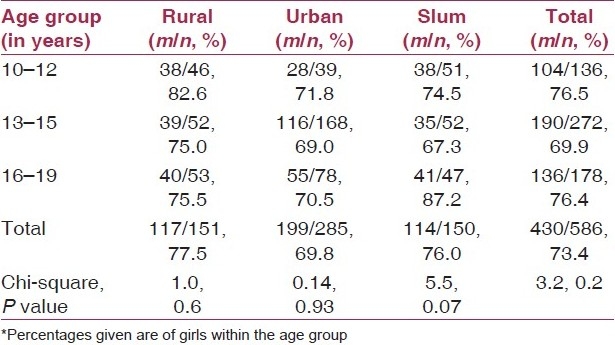

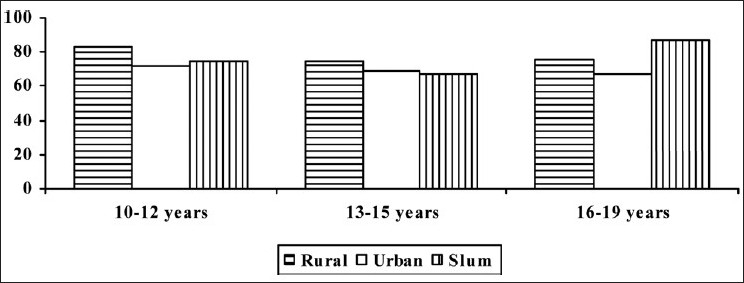

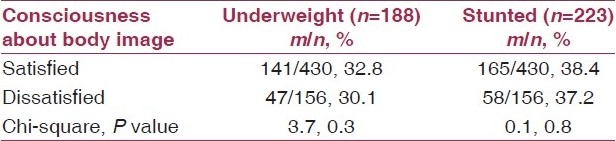

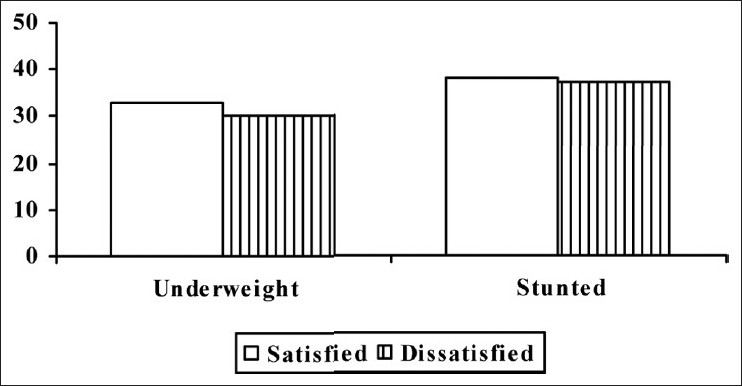

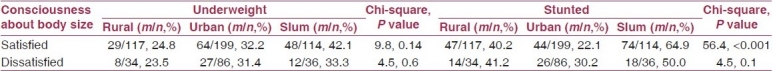

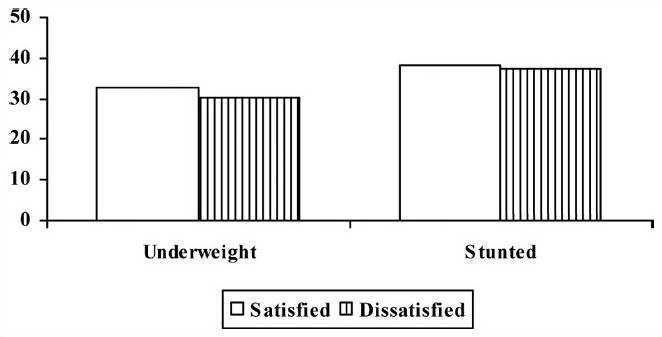

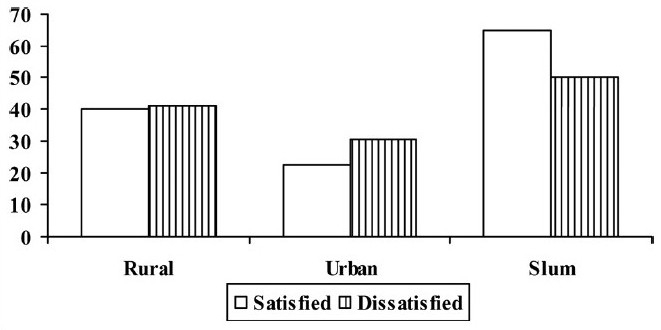

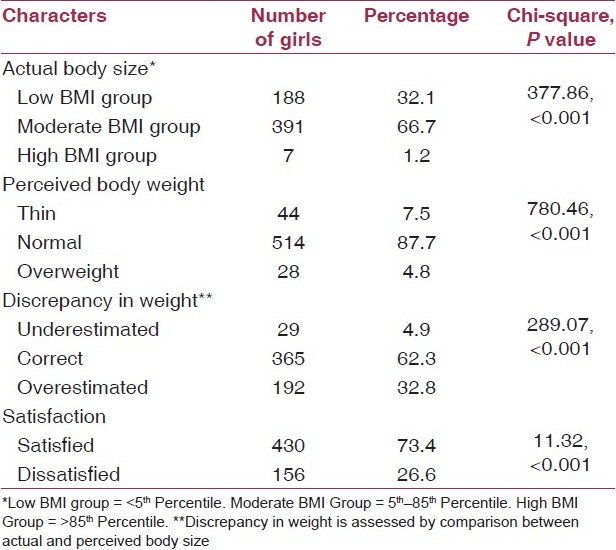

The results indicate there is discrepancy in perceived and desired body size. About one-fifth (20.5%) of girls desire to become thin who already perceived their body image as too thin at the time of their body assessment [Table 1, Figure 1]. Body satisfaction was measured by difference between perceived body image and desired body image. If the perceived and desired body image were same, it is categorized as satisfied. 73.4% adolescent girls were satisfied with their body image, while 26.6% of studied girls were dissatisfied. These prevalence rates of dissatisfaction were higher among girls of urban (30.2%) and slum (40.0%) areas in comparison to rural (22.55) area [Table 2, Figure 2]. Percentage of girls satisfied with their body image was less in the 13–15 years (69.9%) age groups in comparison to 10–12 years (76.5%) and 16–19 years (76.4%) age group. Out of them urban and rural girls of 13–15 years had lower satisfaction with their body image that is 69.0% and 67.3%, respectively, whereas 75.0% of rural girls of age 13–15 years were satisfied with their body image [Table 3, Figure 3]. Results also shows that among the girls who were satisfied with their body image 32.8% girls were underweight and 38.4% were stunted [Table 4, Figure 4]. These numbers of underweight girls (42.1%) and stunted girls (64.9%) were higher in satisfied girls of slum area [Table 5, Figure 5a and 5b]. The difference between actual body weight and perceived body image was used to identifying the estimation about health. Girls who perceived their body image normal (about right and perfect) with normal BMI were categorized into correct estimation, girls of high and medium BMI with thin and normal perceived body image were categorized into underestimation, and girls of low and median BMI with perceived body image of fatty were categorized into overestimation. In present study, 32.8% of girls had overestimated their weight, while only 4.9% of girls had underestimated their weight. Consciousness and attitude of adolescent girls toward current body weight are given in Table 6.

Table 1.

Perceived body image and desired body image

Figure 1.

Perceived body image and desired body image

Table 2.

Consciousness of adolescent girls about their body image

Figure 2.

Consciousness of adolescent girls about their body image

Table 3.

Girls satisfied with their body image in different localities

Figure 3.

Girls satisfied with their body image in different localities

Table 4.

Relation between consciousness about body size and nutritional status of adolescent girls

Figure 4.

Relation between consciousness about body size and nutritional status of adolescent girls

Table 5.

Association of consciousness about body size and nutritional status of adolescent girls of different localities

Figure 5a.

Percentage of underweight girls among the satisfied and dissatisfied group of girls

Figure 5b.

Percentage of stunted girls among the satisfied and dissatisfied group of girls

Table 6.

Consciousness and attitude toward current body weight

Discussion

Very few studies have been conducted in India on the body image perception. In best of our knowledge, it is the first and only paper regarding consciousness of Indian adolescent girls about their body, body perception, body image dissatisfaction, and its association with nutritional status. India is the land of diversities and differences. This thing makes this study even more important because adolescent girls’ subgroups are chosen from three different localities those are rural, urban, and slum area, representing near true picture of the real scenario. Although we do not have any Indian data regarding this specific topic but we have a very interesting interracial study of multiethnic Caribbean adolescent girls’ population. According to this study, thin South Asians were more likely to be satisfied with being thin than the other thin persons. The attitudes of the South Asians adolescents toward thinness were similar to those of white female adolescents in the USA.(16) The results of our study on consciousness of adolescent girls about their body image also indicate that only 26.6% girls are dissatisfied with their body image. It is very similar with the findings of Boschi(4) et al., showing 25% body dissatisfaction among adolescent girls. In our study, this dissatisfaction percentage was higher among the girls of urban and slum area. Body dissatisfaction is a highly significant mediator of the relationship between BMI and eating disorder risk.(17) This may put these girls in an unwanted and undesirable weight correction tendency. They may engage themselves in physical activity to improve the body image (45.2%), while the health improvement motive may left out in the second place (33.6%).(18) As we go to age wise analysis less number of girls satisfied with their body image in the 13–15 years age groups in comparison to 10–12 and 16–19 years age group. This is alike Meland et al.(10) reported finding that in adolescent age group majority of 15-year-old girls wants to change their body, while Abraham and O’Dea(19) reported that females even as young as 12 years of age had tried to lose weight. In our study, setting of three different localities, urban and slum girls of 13–15 years age group have lower satisfaction with their body image in comparison to rural adolescent girls of same age group. Another result also indicates a vital clue about conceptual approach and understanding of girls of this age group about their own body. Among the girls who were satisfied with their body image, approximately one-third (32.8%) of total girls were underweight and more than that (38.4%) were stunted. The number of underweight girls (42.1%) and stunted girls (64.9%) were found higher among satisfied girls of slum area. This indicates about overestimation and misconception of their own body. Lata et al. also reported that 86% of the female adolescent college students desired to be slim. While in that study very few (3.2%) of the female adolescents were actually overweight (BMI). Interestingly, more than 65% perceived themselves to be either slim or thin and 67.7% desired to be slim.(20) In another study regarding misconception of weight among 185 female college students aged 18–24 years, 83% of participants reported ever consciously trying to lose or control their weight, including 80% of normal weight, 91% of overweight, and 86% of obese participants.(21) This kind of approach makes them even more vulnerable for undernourishment, a hidden epidemic of Indian adolescent girls.

Conclusion

The results of study conclude that desire to become thin are higher in adolescent girls even in those who already perceived their body image as too thin. Large numbers of girls are dissatisfied with their body image. Girls of urban areas and even from slums are unconstructively apprehensive about slim figure. It is posing a detrimental threat to their health and nutritional status. These findings suggest an urgent need to encourage adolescent girls for maintaining healthy weight and dietary habits through all possible channels.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Upgraded Department of Community Medicine, CSM Medical University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow, for providing the financial support. Thanks are also due to all the project investigators, all the adolescent girls, their parents, and the community members for their participation during various stages of the project activities.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Upgraded Department of Community Medicine, CSM Medical University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Venkaiah K, Damayanti K, Nayak MU, Vijayaraghavan K. Diet and nutritional status of rural adolescents in India. European J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1119–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hetherington MM. Eating disorders: Diagnosis, etiology, and prevention. Nutrition. 2000;16:547–51. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher M, Golden NH, Katzman DK, Kreipe RE, Rees J, Schebendach J, et al. Eating disorders in adolescents. A background paper. J Adolesc Health. 1995;16:420–37. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boschi V, Siervo M, D’Orsi P, Margiotta N, Trapanese E, Basile F, et al. Body composition, eating behavior, food-body concerns and eating disorders in adolescent girls. Ann Nutr Metab. 2003;47:284–93. doi: 10.1159/000072401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gralen SJ, Levine MP, Smolak L, Murnen SK. Dieting and disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: Do the influences remain the same? Int J Eat Disord. 1990;9:501–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannini M, Agostoni C, Gianni M, Bernardo L, Riva E. Adolescence: Macronutrients needs. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(Suppl 1):7–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olmedilla B, Granado F. Growth and micronutrient needs of adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(Suppl 1):S11–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ballabriga A. Morphological and physiological changes during growth: An update. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(Suppl 1):S1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cash TF, Deagle EA., 3rd The nature and extent of body image disturbances in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:107–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meland E, Haugland S, Breidablik HJ. Body image and perceived health in adolescence. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:342–50. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wertheim E, Paxton SJ, Blaney S. Risk factors for the development of body image disturbances. In: Thompson K, editor. Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity. Hoboken NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. pp. 463–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenblom GD, Lewis M. The relations among body image, physical attractiveness, and body mass in adolescence. Child Dev. 1999;70:50–64. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham S, O’Dea JA. Body mass index, menarche, and perception of dieting among peripubertal adolescent females. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29:23–8. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200101)29:1<23::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Latha KS, Hegde S, Bhat, Sharma P, Rai P. Body image, self-esteem and depression in female adolescent college students. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2006;2:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malinauskas BM, Raedeke TD, Aeby VG, Smith JL, Dallas MB. Dieting practices, weight perceptions, and body composition: A comparison of normal weight, overweight, and obese college females. Nutr J. 2006;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Final Population Totals. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner; 2001. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements, 2003. Nairobi: UN-HABITAT; 2003. United Nations Human Settlements Program. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slum Population, India, Series-I, Census of India 2001. New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner; 2005. Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simeon DT, Rattan RD, Panchoo K, Kungeesingh KV, Ali AC, Abdool PS. Body image of adolescents in a multi-ethnic Caribbean population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:157–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch WC, Heil DP, Wagner E, Michael D. Havens Body Dissatisfaction Mediates the Association between Body Mass Index and Risky Weight Control Behaviors among White and Native American Adolescent Girls Appetite. 2008;51:210–213. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jankauskiene R, Kardelis K. Body image and weight reduction attempts among adolescent girls involved in physical activity Medicina (Kaunas) 2005;41:796–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]