Abstract

Background:

Cancer of the cervix has been considered as one of the preventable cancers. This study is the first published research addressing the screening of cancer of the cervix in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Aim:

This study aims to detect the prevalence of abnormal epithelial changes and its types in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Settings and Study Design:

A retrospective study was designed to evaluate all previously conducted cervical smears examined at a secondary care maternity hospital in Saudi Arabia, during the period from 2003 to 2010. During this period, a total of 1171 smears were reported.

Materials and Methods:

We analyzed the records of all patients who had undergone Papanicolaou (Pap) smear during this period. After data collection, all cases were recorded as per Bethesda nomenclature.

Results:

A total of 624 (53.3%) abnormal Pap smears were found, with only 58 cases reported to have epithelial pathological diagnosis (SIL). They represented 4.95% of total taken smears. A majority of the SIL diagnoses in our population were ASCUS, representing 60% of SIL cases. The prevalence of squamous cervical carcinoma was 0.34%.

Conclusion:

The study has shown a relatively high prevalence of epithelial abnormalities in cervical smears in the studied population. The squamous cell carcinoma represented a higher than the overall prevalence compared to World Health Organization (WHO) factsheets about Saudi Arabia. The mean age of epithelial abnormalities and squamous cell carcinoma was in the reproductive years.

Keywords: Cervical cytology, pap smear, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Worldwide and in Eastern Mediterranean region, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women, after breast cancer. It comes tenth of all cancers in males and females.[1,2] The age standardized rate per 100,000 for cervical cancers among countries of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was 2.1, 2.3, 4.4 and 7 in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain and Oman, respectively.[2] Cervical cancer for the Saudi nationals represented 33.5% of all genital cancers. Current estimates indicate that every year, 271 Saudi women are diagnosed with cervical cancer, with 68 (25.1%) cases occurring in women of child-bearing age. Of these 271 women, 143 (52.8%) will die due to the disease, including 27 (39.7%) at the child-bearing age.[3–4]

National Health Services (NHS) in UK concluded that, in any case who developed cancer cervix at the average age 46-50, this may entail that carcinogenesis had started 20 years ago, ie, at the age of 26-30. Hence, screening is better to be started at >25 years.[5] In Saudi Arabia, only 29% of breast cancer and 35% of cervical cancer cases present at an early stage.[6]

To address the need for screening in Saudi Arabia, it is important to document the magnitude of cervical pre-neoplastic lesions. Searching the literature for such studies revealed few studies from Saudi Arabia; all were carried out in the Western or South Western regions of Saudi Arabia.[7–12]

The primary aim of this study was to explore the cytopathological profile of the uterine cervix in women attending secondary care maternity hospital in Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods

Al Ahsa region is the largest area in the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia, with a population of about 1.5 million. The maternity hospital in this region is a large secondary care facility serving all population, with about 30,000 cases per year attending the Obstetrics or Gynecology clinics. According to the demography of the area and this hospital being the major maternity hospital in the region, the attending population represented the urban, rural as well as small desert localities.

A retrospective cross-sectional observational study was designed to review the Papanicolaou (Pap) smears from the archives of the Department of Clinical Pathology, over the period starting from 2003 to 2010 (1424-1431 Hijri). The study sample was taken from all the available Pap smears in that period. The research was accepted by the MCH and no ethical concerns were present. All efforts were made to assure data confidentiality and the research publication is only for the purpose of improving services.

All cases were instructed for precautions before cytological examination, eg, douching and coitus. Cytological smears that were collected only by the Ayre's spatula were included (Some samples were not included, as they were wrongly taken by tongue depressor from only the ectocervix). Ayre's spatula was rotated five times in the clockwise direction, with the central longer bristles in the canal. All efforts were made to obtain quality samples around mid-cycle to ensure reliability of the test. The spatula with the sample was rapidly but lightly stroked, thinly and evenly across the surface of the slide and cytology spray fixatives were used without any delay. All slides were evaluated at the cytology laboratory of the hospital by using light microscopy and the modified Pap method.[13] Smears were prepared by cytotechnologists and all slides were read by the consultant histopathologist. All reports gave the complete diagnosis despite they were in non-uniform in pattern, with no specific classification scheme in the reporting of these smears.

The cytological information were collected from the Pap smear reports included three major categories: Unsatisfactory, normal or abnormal smears. Abnormal smears were subdivided into either abnormal epithelial lesions (SIL) or negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM). Epithelial abnormalities reported in the hospital included CIN I, CIN II and CIN III; Positive for malignant cells; atypical endocervical cells; atypical squamous cells; squamous metaplasia with atypia; reparative atypia; squamous cell carcinoma (SCC); and atypical glandular cells of unknown origin. NILM included benign cellular changes as reactive cellular changes, inflammatory and atrophic smears.

All reported cases were read carefully and assigned a category according to the Bethesda system 2001.[14] All abnormal epithelial lesions (SIL) were named: Atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS) and other atypical cells not otherwise specified. The malignant categories were SCC, adenocarcinoma and other malignancy not otherwise specified.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence was calculated from the number of positive cases divided by the number of tested specimens. Descriptive statistics were used and number and percentage were tabulated. Cytopathological aspects of Pap smears were reviewed with age distribution. Percentage distribution of each diagnosis has been mentioned and calculated out of abnormal Pap smears and out of total cervical Pap smears. All analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

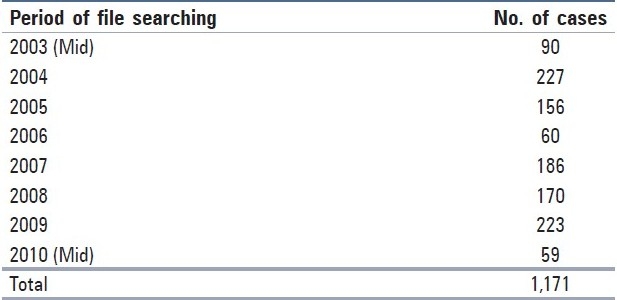

A total of 1,171 cases of cervical Pap smears were retrieved from the archives of the laboratory during the study period. Table 1 presents the distribution of these cases per year of investigation.

Table 1.

Number of cases found according to the year in the archive

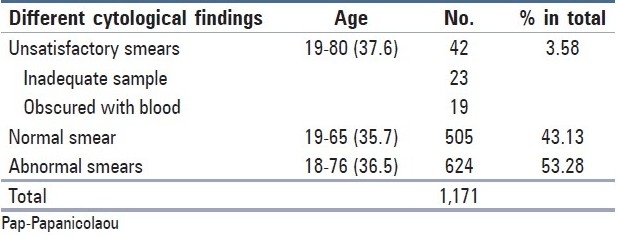

There were 624 (53.3%) abnormal Pap smears (epithelial cell abnormalities as well as benign cellular changes of inflammation, repair, etc.), with 505 normal cases (43.13%) and 42 unsatisfactory or inadequate samples (3.28%). The inadequate or smears obscured with blood were allocated in the unsatisfactory group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Common findings in all the Pap smears with respect to mean age

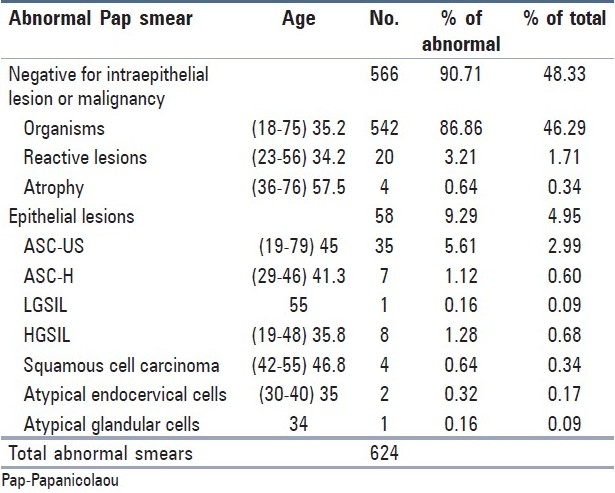

Of the 624 abnormal cases, only 58 cases were reported to have epithelial pathological diagnosis. They represented 9.29% of abnormal Pap smears and 4.95% of total smears taken. The diagnosis of the 58 abnormal cases with their mean ages revealed 35 cases with ASC-US (45 years), 7 cases of ASC-H (41.3), 1 case of LSIL (55), 8 cases of HSIL (35.8), 1 case of AGUS (34 years), 2 cases of atypical endocervical cells (35 years) and 4 cases of SCC (35.8 years) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Number and percentage of the specific findings in the abnormal Pap smears with respect to the mean age

Discussion

The literature is overwhelmed with evidences supporting the importance of early detection of precancerous lesions of the cervix by cytological examination using Pap smear. The Saudi health sector is making remarkable efforts in all fields of preventive healthcare. Multiple National screening programmes are evolving. Cancer cervix screening programme was launched in 2009. The current study is the first report of an analysis of the cervical Pap smear reports from the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia has a population of 6.51 million women aged 15 years and older who are at risk of developing cervical cancer. Current estimates indicate that every year 152 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 55 die from the disease. Cervical cancer ranks as the 11th most frequent cancer among women in Saudi Arabia, and the 8th most frequent cancer among women in the age group of 15-44 years.[15]

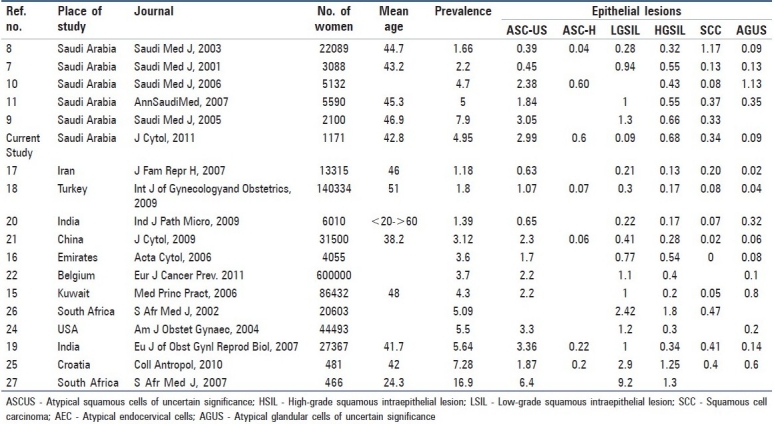

With reference to detection of cervical epithelial abnormalities in cervical smears, the previously published studies from Saudi Arabia showed variable results. The prevalence rates of abnormal epithelial changes are in the range of 1.66-7.9%.[8,9] Two studies showed similar prevalence to our current findings.[10,11] The mean age of the cases diagnosed as SCC was 35.8 years. The average age of SCC in all the Saudi studies was nearly similar. That age was clearly within the reproductive years.[7–11]

The largest study in Gulf countries was carried out in Kuwait, with an evaluation of 86,434 cervical smears over a period of 13 years and reported a prevalence rate of 4.3% of cervical epithelial abnormalities. ASCUS represented the most common finding: 1,790 cases (2.2%).[16] A study conducted in Emirates showed the prevalence of cervical epithelial abnormalities as 3.6%. The prevalence of ASCUS was 1.7%.[17] These studies showed a similar overall prevalence of the epithelial abnormalities such as that shown by the current study. However, we recorded more cases of HGSIL and SCC.

In Iran, the studies reported an overall incidence of epithelial abnormalities as 1.18%. Carcinoma and AGC represented 0.02%.[18] The largest reported study in the Middle East was from Turkey. From 140,334 cases, an overall prevalence of cytological abnormality was 1.8%. Among the cervical cytology specimens, 0.04% was classified as SCC.[19] Both the overall prevalence and the cases reported as carcinoma were less than the findings in the current study. These low figures in two of the Islamic countries where the religious factors are nearly similar to our situation may denote a more advanced step towards the awareness and screening programmes, and hence less advanced cases.

One of the largest Indian studies reported values supporting our results. The overall epithelial abnormalities represented 5.64%. Abnormal cervical cytology lesions such as ASCUS, HSIL, LSIL, carcinoma and AGUS represented 3.36%, 1%, 0.34%, 0.41% and 0.13%, respectively.[20] On the other hand, another Indian study conducted on urban hospital cases reported a much lower prevalence of epithelial abnormalities, ie, 1.39%. ASCUS, LSIL, HSIL and SCC represented 0.64%, 0.216%, 0.16% and 0.07%, respectively.[21] This may be explained by the different conditions prevalent in each study, with less prevalence in the urban studies as they may represent situations of good screening programmes and also the hygienic conditions could not be guaranteed in the settings of low resources.

In China, conventional Pap smear test revealed an overall epithelial abnormality in 3.12% of patients. Abnormal cervical cytology lesions; ASCUS, HSIL, LSIL, carcinoma and AGUS represented 2.3%, 0.41%, 0.28%, 0.06% and 0.02%, respectively.[22] Limburg Cancer Registry in Belgium reported a 3.7% prevalence of cytological abnormalities out of 600,000 Pap smears. ASCUS, AGC, LGSIL, HGSIL and more serious conditions were found in 2.2%, 0.1%, 1.1% and 0.4%, respectively.[23] These low figures than our study may be due to the larger samples used and widely used screening programmes.

In a general healthcare setting in the US, 5.5% of routinely screened women were found to have an abnormal cervical smear. ASCUS was present in 3.3%.[24] One study in Croatia reported abnormal cervical cytology to be 7.28%. ASCUS and LSIL were the most common findings.[25] Two studies from South Africa reported diverse findings. The first was similar to that reported in our study, with one exception that they reported a higher SCC prevalence.[26] The second study showed markedly higher prevalence than our study, with a positive significant correlation between epithelial abnormalities and HIV infection.[27]

The current study shows a relatively high prevalence of epithelial abnormalities in cervical smears in the population studied. The SCC represented a higher figure than the overall prevalence appeared in the World Health Organization (WHO) factsheets about Saudi Arabia. Multiple limitations were encountered in this study. The small size of the sample (despite that it represented all the cases within 7 years) and the small numbers of epithelial abnormalities did not allow for more stratification by age groups to study which age group has more of the diagnosed epithelial abnormalities. Our sample represented cases taken only by chance and does not include all community and healthy cases. For better estimates of the prevalence of cervical disease, larger population-based studies should be conducted. Lastly, the study design was retrospective. Prospective studies are more important and carry more weightage as a piece of evidence.

The authors reviewed a number of studies and arranged them according to the prevalence of epithelial abnormalities, which showed marked variability [Table 4]. The reasons for these variable findings could include variable employed laboratory criteria for diagnosis and intrinsic differences in the nature of samples. The difference in the prevalence of certain sexually transmitted infections such as human papillomavirus (HPV)—being a possible risk factor—may also give reasons for the variable findings. The attitude of healthcare providers with regard to the screening time and effort may incapacitate some trials for massive screening. Also, we should not ignore the client fear and perspective regarding this sensitive issue of screening of HPV and its related disease.

Table 4.

Prevalence of abnormal epithelial abnormalities in different studies ranked by prevalence

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Feslay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GLOBOCAN. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2008. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 25]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/cancers/cervix.asp .

- 3.Makoha FW, Raheem MA. Gynecological cancer incidence in a hospital population in Saudi Arabia: the effect of foreign immigration over two decades. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(Suppl 4):538–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO/ICO. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 25];Summary report on HPV and cervical cancer statistics in Saudi Arabia. 2007 4:3–12. Available from: http://www.abms.org/newsearch.asp . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Effectiveness of cervical screening with age: population based case-control study of prospectively recorded data. BMJ. 2009;339:b2968. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO/EM/NCD/060/E/7.09/400. Towards a strategy for cancer prevention and control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2009. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 25]. Available from: http://www.abms.org/newsearch.asp .

- 7.Altaf FJ. Pattern of cervical smear cytology in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamal A, Al-Maghrabi JA. Profile of PAP smear cytology in the Western region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elhakeem HA, Al-Ghamdi AS, Al-Maghrabi JA. Cytopathological pattern of cervical PAP smear according to the Bethesda system in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:588–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altaf FJ. Cervical cancer screening with pattern of pap smear.Review of multicenter studies. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdullah LS. Pattern of abnormal Pap smears in developing countries: a report from a large referral hospital in Saudi Arabia using the revised 2001 Bethesda System. Ann Saudi Med. 2007;27:268–72. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2007.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Jaroudi D, Hussain TZ. Prevalence of abnormal cervical cytology among sub fertile Saudi women. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:397–400. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.68550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koss LG, editor. Diagnostic cytology and its histopathologic bases. 4th ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, Moriarty A, O’Connor D, Prey M, et al. Forum Group Members; Bethesda 2001 Workshop.The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287:2114–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO/ICO. Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer, Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet 2010. [Last cited on 2010 Dec 25]. Available from: http://www.abms.org/newsearch.asp .

- 16.Kapila K, George SS, Al-Shaheen A, Al Ottibi MS, Pathan SK, Sheikh ZA, et al. Changing spectrum of squamous cell abnormalities observed on papanicolaou smears in Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital, Kuwait, over a 13 year period. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:253–9. doi: 10.1159/000092986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghazal-Aswad S, Gargash H, Badrinath P, Al-Sharhan MA, Sidky I, Osman N, et al. Cervical smear abnormalities in the United Arab Emirates: A pilot study in the Arabian Gulf. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:41–7. doi: 10.1159/000325893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afrakhteh M, Khodakarami N, Moradi A, Alavi E, Shirazi F H. A study of 13315 papanicolaou smear diagnoses in Shohada Hospital. J Fam Reprod Health. 2007;1:74–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkish Cervical Cancer and Cervical Cytology Research Group. Prevalence of cervical cytological abnormalities in Turkey. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;106:206–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Sodhani P, Halder K, Chachra KL, Sardana S, Singh V, et al. Spectrum of epithelial cell abnormalities of uterine cervix in a cervical cancer screening programme: implications for resource limited settings. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134:238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulay K, Swain M, Patra S, Gowrishankar S. A comparative study of cervical smears in an urban Hospital in India and a population-based screening program in Mauritius. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:34–7. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshou H, Changhua W, Qinyan L, Wei L, Wen F. Clinical utility of Liqui-PREP™ cytology system for primary cervical cancer screening in a large urban hospital setting in China. J Cytol. 2009;26:20–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.54863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbyn M, Van Nieuwenhuyse A, Bogers J, De Jonge E, De Beeck LO, Matheï C, et al. Cytological screening for cervical cancer in the province of Limburg, Belgium. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:18–24. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833ecbc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB. Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: a population based study. Am J Obstet Gynaec. 2004;191:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skopljanac-Macina L, Mahovlić V, Ovanin-Rakić A, Barisić A, Rajhvajn S, Juric D, et al. Cervix cancer screening in Croatia within the European Cervical Cancer Prevention Week. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonn S, Bloch B, Mabina M, Carpenter S, Cronje H, Maise C, et al. Prevalence of pre-cancerous lesions and cervical cancer in South Africa: A multicentre study. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:148–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaym A, Mashego M, Kharsany AB, Walldorf J, Frohlich J, Karim QA. High prevalence of abnormal Pap smears among young women co-infected with HIV in rural South Africa - implications for cervical cancer screening policies in high HIV prevalence populations. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]