Abstract

Crouzon's syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder with complete penetrance and variable expressivity. Described by a French neurosurgeon in 1912, it is a rare genetic disorder. Crouzon's syndrome is caused by mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) gene. Normally, the sutures in the human skull fuse after the complete growth of the brain, but if any of these sutures close early then it may interfere with the growth of the brain. The disease is characterized by premature synostosis of coronal and sagittal sutures which begins in the first year of life. Case report of a 7 year old boy is presented with characteristic features of Crouzon's syndrome with mental retardation. The clinical, radiographic features along with the complete oral rehabilitation done under general anesthesia and preventive procedures done are described.

Keywords: Crouzon's syndrome, fibroblast growth factor, premature synostosis

Introduction

Cranial skeletogenesis is unique. The cranial skeleton is composed of an assortment of neural crest and mesoderm- derived cartilages and bones that have been highly modified during evolution. Cranial malformations, although uncommon, compromise not only function but also the mental well-being of the person. Recent advances in human genetics have increased our understanding of the ways particular gene perturbations produce cranial skeletal malformations.[1] However, an abnormal head shape resulting from cranial malformations in infants and children continues to be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge.

Crouzon's syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder with complete penetrance and variable expressivity or can appear as a mutation.[2] Described by a French neurosurgeon Octave Crouzon in 1912,[3] it is a rare genetic disorder. It may be transmitted as an autosomal dominant genetic condition. Crouzon syndrome is caused by mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) genes.[4] The disease is characterized by premature synostosis of coronal and sagittal sutures which begins in the first year of life. Once the sutures become closed, growth potential to those sutures is restricted. However, multiple sutural synostoses frequently extend to premature fusion of skull base causing midfacial hypoplasia, shallow orbit, maxillary hypoplasia, and occasional upper airway obstruction.[5] Intraoral manifestations include mandibular prognathism, overcrowding of upper teeth, and V-shaped maxillary dental arch.[3] Narrow, high, or cleft palate and bifid uvula can also be seen. Occasional oligodontia, macrodontia, peg-shaped, and widely spaced teeth have been reported.[3,5]

Crouzon's syndrome occurs in approximately 1 in 25,000 births worldwide.[6] Prevalence in the United States is 1 per 60,000.[7] Crouzon syndrome makes up approximately 4.8% of all cases of craniosynostoses.[8] No known race or sex predilection exists.[5] The differential diagnosis of Crouzon's syndrome includes simple craniosynostosis as well as Apert syndrome, Carpenters syndrome, Saethre-Chotzen syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome.[9]

While cases have been documented, seldom have reported with mental retardation and also very few have been found on the oral rehabilitation inclusive of preventive procedures in these children. This case report presents a child of 7 years with Crouzon's syndrome.

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy along with his parents reported to our department for treatment. The chief complaint being as presented by the mother was pain in relation to the child's upper left teeth since 2 days. Since the child's appearance and head size was not normal, the family and medical history were taken in detail before referring the child to the pediatrician and psychologist for their expertise. The pediatrician and psychologist did diagnose the child with Crouzon's syndrome associated with mild to moderate mental retardation. Review of medical history was unremarkable, specifically, the mother reported normal labor and delivery. There were no anomalies in any siblings or near relatives reported. The child was not on any medications and denied any medical allergies. He has never been to a dentist before and this was the first dental consultation. Further medical history revealed that the enlarged size of the head was noted by the mother ever since he was 6 months and the severity has gradually increased.

On examination

Extra-oral examination revealed elliptical-shaped head, with dolichofacial growth pattern, and convex facial profile. The presence of prominent eyeballs, which is the characteristics of the Crouzon disease triad, can be observed [Figure 1a and b].

Figure 1a.

Extraoral appearance

Figure 1b.

Profile of the patient

Intra-oral examination showed that the patient is in early mixed dentition, with all primary teeth present in the maxillary and mandibular arch, the chronology of eruption and eruption status was normal for the child's age. The child also had a high arched palate which is typical of this syndrome. The deciduous teeth that were present were grossly decayed owing to the poor oral hygiene maintained because of lack of awareness on part of the parents and also partly due to the mental condition of the child. The permanent first molars which were erupted were in occlusion and healthy. The orthopantamograph (OPG) which was taken confirmed these findings. The OPG also showed the presence of all succedaneous teeth which looked healthy but the teeth on the left mandibular quadrant appear to have macrodontia which again is a feature which has been reported [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Orthopantamograph of the patient

The treatment plan

Keeping in view the mental condition and behavior pattern of the child and also the fact that so many teeth were to be extracted and restored we decided to carry out complete oral rehabilitation under general anesthesia followed by fabrication of functional space maintainer and a regular preventive regimen for which the parents would have to get the child to us on a periodic basis.

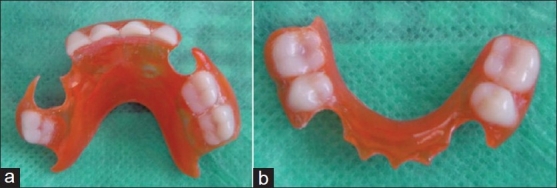

The rehabilitation was completed with an oral prophylaxis, the extraction of all the grossly decayed primary teeth, and the restoration of all the deciduous canines with glass ionomer cement. Impressions of the maxillary and mandibular arches were made for the fabrication of a functional space maintainer [Figure 3a and b]. The teeth extracted were all grossly decayed which could not be saved and also anterior teeth which showed preshedding mobility were extracted.

Figure 3.

(a) The maxillary removable functional space maintainer made for the child. (b) The mandibular removable functional space maintainer

The child was discharged on the following day and recalled after a week for follow up. The healing of the extraction sockets was uneventful and no other complications were reported. The removable functional space maintainer which was made with the child's favorite color was delivered to him.

Preventive protocol applied

The preventive regimen consisted of regular follow up every 2 months wherein based on the presenting eruption status, the functional space maintainer would be modified by trimming the same. A specially designed handle for his toothbrush was fabricated using self-cure resin so that he was comfortable using it [Figure 4]. At the subsequent follow ups for the next 2 months, topical fluoride varnish was painted on his permanent teeth and also on the remaining of the primary teeth. The child is also found to be coping with his space maintainer appliance quiet successfully. The child is been considered for further treatment by the oral and maxillofacial surgeons, pediatricians, and psychologists for his requirements.

Figure 4.

Custom-made tooth brush made for the child

We also will try and use interceptive orthodontics at the right time to treat his mid-face deficiency thereby improving his facial profile and appearance as early orthodontic intervention will prevent many malocclusions from developing.

Discussion

Craniofacial abnormalities are often present at birth and may progress with time.

Crouzon's syndrome is an autosomal-dominant disorder with complete penetrance and variable expressivity, but about one third of the cases do arise spontaneously. The male to female preponderance is 3:1.[2,10] With the advent of molecular technology, the gene for Crouzon's syndrome could be localized to the fibroblast growth factor receptor II gene (FGFR 2) at the chromosomal locus 10q 25.3-q26, and more than 30 different mutations within the gene have been documented in separate families.

Differential diagnosis of Crouzon's syndrome considers Apert syndrome and other problems including Carpenter syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome, Seatre-Chotzen syndrome, and Jackson Weiss syndrome. Patients with associated acanthoses migricans can have FGFR3 mutation.[10]

The appearance of an infant with Crouzon's syndrome can vary in severity from a mild presentation with subtle midface deficiency to severe forms with multiple cranial sutures fused and marked midface and eye problems. Upper airway obstruction can lead to acute respiratory distress and the presence of mental retardation is rare in these children.[3,11] Increased intracranial pressure leading to optic atrophy may occur, which can produce blindness if the condition is not treated.

Management of Crouzon's disease is multidisciplinary and early diagnosis is important. In the first year of life, it is preferred to release the synostotic sutures of the skull to allow adequate cranial volume thus allowing for brain growth and expansion. Skull reshaping may need to be repeated as the child grows to give the best possible results.[6,11] If necessary, mid-facial advancement and jaw surgery can be done to provide adequate orbital volume and reduce the exophthalmoses to correct the occlusion to an appropriate functional position and to provide for a more normal appearance. Prognosis depends on malformation severity.[6,11]

Our patient reported late with the syndrome and was never treated for it. His oral hygiene was compromised owing to his mental retardation and the lack of awareness on the part of the parents. Complete oral rehabilitation was performed under GA. The child did recover uneventfully and is undergoing regular follow ups for his preventive oral hygiene protocol. Although the child was initially apprehensive about his appliance, but now is coping well with the same. We also are contemplating for interceptive orthodontics after obtaining consensus from the other specialties involved so as to prevent any developing malocclusion. He has also been referred to department of oral and maxillofacial surgery to reduce his skull deformity so as to prevent complications which may arise as a result of increased intracranial pressure. He is also meeting the psychologist and pediatricians at our institute with his parents. We expect him to have a normal and healthy life span after all his treatment is completed.

Conclusions

An understanding of these abnormalities is necessary for the dental team to make the appropriate referrals to insure the patient receives the best available care. The Pediatric Dentist should be an integral part of the multidisciplinary team.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Helms JA, Schneider RA. Cranial skeletal biology. Nature. 2003;423:326–31. doi: 10.1038/nature01656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogh-Andersen P. Craniofacial dysostosis (Crouzon's disease) as a dominant hereditary affection. Nord Med. 1943;18:993–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crouzon LE. Dysostose cranio-faciale héréditaire. Bulletin de la Société des Médecins des Hôpitaux de Paris. 1912;33:545–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fries PD, Katowitz JA. Congenital craniofacial anomalies of ophthalmic importance. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;35:87–119. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(90)90067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hlongwa P. Early orthodontic management of Crouzon Syndrome: A case report. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2009;8:74–6. doi: 10.1007/s12663-009-0018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MM., Jr Craniosynostosis update 1987. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1988;4:99–148. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320310514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MM, Jr, Kreiborg S. Birth prevalence studies of the Crouzon syndrome: Comparison of direct and indirect methods. Clin Genet. 1992;41:12–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1992.tb03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray TL, Casey T, Selva D, Anderson PJ, David DJ. Ophthalmic sequelae of Crouzon syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders co; 1999. Oral pathology–Clinical pathologic correlations; pp. 477–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Levin LS. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1990. Syndromes of the head and neck; pp. 516–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarund M, Lauritzen C. Craniofacial dysostosis: Airway obstruction and craniofacial surgery. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30:275–9. doi: 10.3109/02844319609056405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]