Abstract

The topological organization of a TATA binding protein-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNA polymerase II (RNAP II)-TFIIE-promoter complex was analyzed using site-specific protein-DNA photo-cross-linking of gel-purified complexes. The cross-linking results for the subunits of RNAP II were used to determine the path of promoter DNA against the structure of the enzyme. The results indicate that promoter DNA wraps around the mobile clamp of RNAP II. Cross-linking of TFIIF and TFIIE both upstream of the TATA element and downstream of the transcription start site suggests that both factors associate with the RNAP II mobile clamp. TFIIEα closely approaches promoter DNA at nucleotide −10, a position immediately upstream of the transcription bubble in the open complex. Increased stimulation of transcription initiation by TFIIEα is obtained when the DNA template is artificially premelted in the −11/−1 region, suggesting that TFIIEα facilitates open complex formation, possibly through its interaction with the upstream end of the partially opened transcription bubble. These results support the central roles of the mobile clamp of RNAP II and TFIIE in transcription initiation.

RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) is the 12-subunit enzyme that synthesizes all mammalian mRNA (5, 58). Biochemical analyses have revealed that the transcription reaction involves a number of successive steps that lead to the formation of a pre-mRNA (19, 38). In the first step, RNAP II locates promoter DNA and positions its catalytic center near the transcriptional initiation site of the promoter DNA. This first step proceeds through the formation of a preinitiation complex that contains, in addition to RNAP II, a number of general initiation factors, including TATA binding protein (TBP), TFIIB, TFIIF, TFIIE, and TFIIH. Assembly of the preinitiation complex requires specific binding of some general initiation factors to core promoter elements, such as binding of TBP to the TATA box (3), TFIIB to the TFIIB recognition element (29), and TAFs of TFIID to Inr (50) and the downstream promoter element (2). Formation of the preinitiation complex is accompanied by topological changes, including bending and wrapping of promoter DNA around the protein core of the complex (13, 28, 30, 36, 42, 45). Recent evidence indicates that DNA wrapping during transcription initiation is required for the accurate positioning of the initiation site near the enzyme catalytic center and the induction of topological constraints essential for promoter melting (8, 42). In the second step, promoter DNA between nucleotides (nt) −9 and +2 is melted in such a way that the template strand becomes accessible to NTP polymerization (21, 23, 26, 57). Both TFIIF and TFIIE were shown to participate in promoter melting (22, 39). Full open-complex formation requires the action of the ATP-dependent helicase activity of TFIIH (21, 23). Two distinct single-stranded DNA helicases, XPB/p89 and XPD/p80, have been identified as components of TFIIH (46-48, 53, 56). A major role in promoter DNA melting prior to initiation was attributed to XPB/p89 (27, 54). During the third step, RNAP II enters a cycle of abortive initiation events in which the enzyme synthesizes many short 2- to 10-nt transcripts (21). A structural transition within the initiation complex, including a remodeling of the transcription bubble, occurs when RNAP II reaches register 11 and enters the processive phase of the transcription reaction (21). TFIIH is responsible for the melting of the template DNA during promoter escape (16, 32, 51) and for the phosphorylation of the RNAP II carboxy-terminal domain (10, 31, 49). Formation of the mRNA is completed through transcript elongation and is followed by termination of the transcription reaction.

The availability of crystal structures for both eukaryotic (6, 7, 14, 15) and prokaryotic (4, 33, 34, 55, 59) RNAPs has been invaluable for the understanding of the many molecular features of the transcription reaction. For example, the structure of elongating RNAP II has revealed the position of the RNA-DNA duplex formed during the transcription reaction (15). The available structures support a model in which the DNA enters the enzyme through a channel formed by a pair of “jaws” before accessing a deep cleft, at the bottom of which is buried the active site with its Mg2+ ions; the DNA then turns by ∼90o along a wall, where the upstream end exits the enzyme (15). Recently, the crystal structure of the Thermus aquaticus RNAP holoenzyme bound to a fork junction DNA fragment was resolved (33). The structure shows that the DNA lies across one face of the holoenzyme, completely outside the active-site channel. A similar high-resolution structure remains to be obtained for RNAP II.

Over the years, site-specific protein-DNA photo-cross-linking has been used to analyze the topological organization of RNAP II complexes bound to DNA. The results indicate that the RNAP II preinitiation complex forms a very compact structure in which the DNA is tightly bent and wrapped against the core of the complex (13, 45). Our proposed model, named the DNA-wrapping model, describes basal transcription mechanisms (5). However, two puzzling features stand out from our cross-linking results: (i) some subunits of the complex cross-link to a very extensive region of the promoter, and (ii) some promoter positions can cross-link many different polypeptides. One possible explanation for these observations stems from the fact that our cross-linking procedure was performed on protein-DNA complexes that were not purified after assembly, possibly allowing the formation of a heterogeneous subpopulation of minor complexes in addition to the main complex. These subcomplexes may result from nonspecific interactions between components of the transcription machinery and promoter DNA. In order to circumvent this possible caveat and to improve the resolution of our photo-cross-linking procedure, we have developed an in-gel protein-DNA photo-cross-linking method in which protein-DNA complexes are separated using native gel electrophoresis prior to their UV irradiation and extraction from the gel. We report here the use of this method to study cross-linking of the transcription machinery assembled into a TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE-promoter complex. As expected, this in-gel photo-cross-linking methodology increases the resolution by allowing more precise localization of the various factors along the promoter DNA. Our results suggest key roles both for the mobile clamp of RNAP II and for TFIIE during the preinitiation stage of transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein factors.

Recombinant yeast TBP (25), human TFIIB (18), RAP30 (11), RAP74 (11), TFIIEα and TFIIEβ (37, 41, 52), and calf thymus RNAP II (20) were prepared as previously described.

In-gel photo-cross-linking.

The photoreactive nucleotides azidobenzoic (AB)-dUTP and AB-(Gly)2-dUTP were synthesized as described by Bartholomew and colleagues and Persinger and Bartholomew (1, 40). The in-gel photo-cross-linking procedure was performed as recently described (12). Briefly, various photoprobes placing one or two photonucleotides in juxtaposition to one (or a few) radiolabeled nucleotide at a specific position along promoter DNA were prepared enzymatically and gel purified. Each probe was incubated for 30 min at 37°C with highly purified RNAP II and recombinant general initiation factors (see below and figure legends for details) and then loaded on a polyacrylamide-N,N′-bisacryloylcystamine native gel (35). The gels were run in a cold room and irradiated with UV light (254 nm), and the complexes were localized using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Gel slices containing the complexes were excised and solubilized with dithiothreitol (0.4 M final concentration). The cross-linked complexes were then treated with S1 nuclease and DNase I prior to analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as previously described (44). Immunoprecipitation of the cross-linking products used specific antibodies directed against the various subunits of the general transcription factors as previously described (44).

Initiation assay.

Abortive initiation assays were done essentially as previously described (30, 39) with the following modifications. Double-stranded oligonucleotide templates (12 ng) carrying the adenovirus major late promoter from −45 to +35 were incubated for 60 min at 30°C with TBP (60 ng), TFIIB (30 ng), RAP74 (65 ng), RAP30 (30 ng), RNAP II (165 ng), TFIIEβ (40 ng), and, when indicated, TFIIEα (60 ng) in 20 μl of a reaction mixture containing 750 μM ATP, 750 μM CTP, 10 μM UTP, 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 3 mM EGTA, and 0.84 U of RNase inhibitor/ml. After the reaction was stopped, the mixture was treated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (8 U) in order to reduce the background caused by free radiolabeled nucleotides. Transcripts were analyzed on a 23% polyacrylamide denaturing gel containing 7 M urea and quantified using a PhosphorImager.

Computer modeling.

Prediction of low-energy AB-dUMP and AB-(Gly)2-dUMP conformers was performed using the Sybyl Molecular Modeling Package (version 6.4; Tripos Associates, St. Louis, Mo.). The models (see Fig. 6) were built by importing the RNAP II (accession code, 1I50) and TBP-TFIIB-DNA (accession code, 1Vol) PDB files from SWISS-PDB version 3.7 (17) and VMD version 1.7.2 (24) into the Cinema 4D XL Modeling Package (version 6.3; Maxon Computer, Thousand Oaks, Calif.).

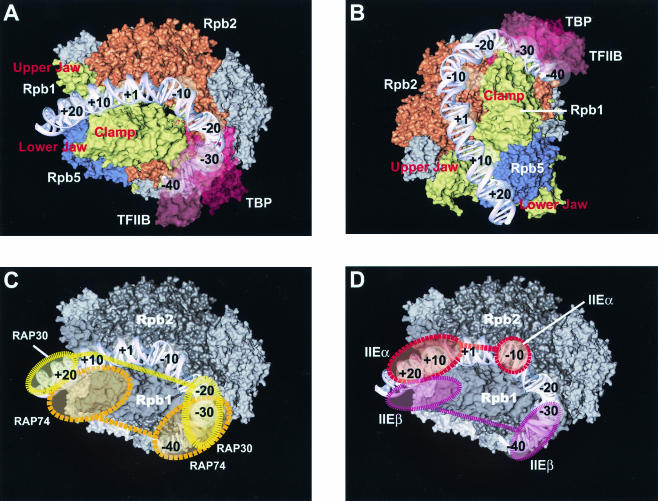

FIG. 6.

Topological model of the RNAP II preinitiation complex. (A and B) Top (A) and side (B) of the proposed trajectory of the promoter DNA around the mobile clamp of RNAP II. The path of promoter DNA has been drawn to account for our in-gel photo-cross-linking results (see the text). (C and D) Locations of TFIIF (C) and TFIIE (D) subunits according to our photo-cross-linking results. For each subunit, we obtained cross-linking to two distinct promoter regions (dashed circles). Although our results suggest that two copies each of TFIIE and TFIIF subunits are present within the complex, we cannot rule out the possibility that these factors have two (or more) distinct domains held together by an unfolded linker.

RESULTS

Photo-cross-linking of gel-purified RNAP II preinitiation complexes.

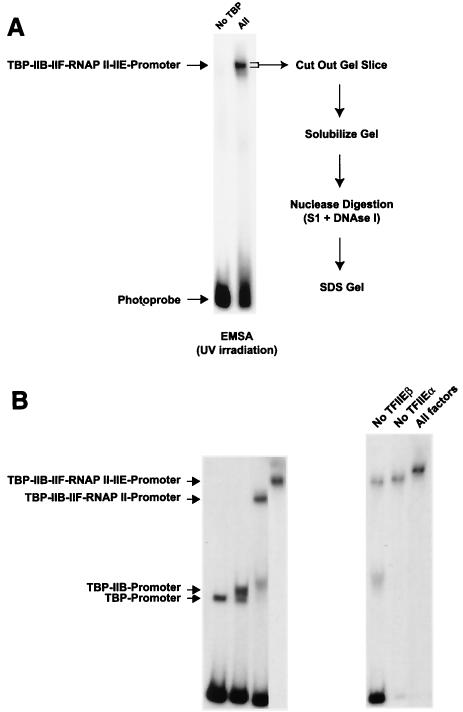

To analyze the molecular organization of the RNAP II preinitiation complex, we developed a procedure for photo-cross-linking proteins to specific sites along promoter DNA following purification of the protein-DNA complexes by electrophoresis in native gels. A total of 12 different photoprobes that place one or two photoreactive nucleotides in juxtaposition to one or a few radiolabeled nucleotides at specific positions along the adenovirus major late promoter (Fig. 1A) were used to analyze the promoter contacts by a TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE complex. Recombinant TBP, TFIIB, RAP74, RAP30, TFIIEα, TFIIEβ, and highly purified RNAP II were mixed with the various photoprobes, and the resulting complexes were separated on native polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 2A). The gels were irradiated with UV light, and gel slices containing the protein-DNA complexes were excised. Using this procedure, any intermediate complex that may have formed was disregarded. After dissolution of the gel fragments, the samples were treated with nucleases and the cross-linked polypeptides were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The cross-linked polypeptides were visualized by autoradiography of the gels and identified according to their molecular weights. The identities of the cross-linked polypeptides were confirmed either by immunoprecipitation of the cross-linking products with specific antibodies or by using tagged factors in the cross-linking reactions. The results of at least four independent experiments using each individual photoprobe were compiled to produce Fig. 3, which shows the cross-links that were reproducibly obtained. In each case, a control reaction lacking TBP was assembled to ensure promoter binding specificity (Fig. 2A shows an example). We also performed gel mobility shift experiments using subsets of the general initiation factors and RNAP II to ensure that our conditions for complex assembly allowed the formation of a bona fide TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE-promoter complex (Fig. 2B).

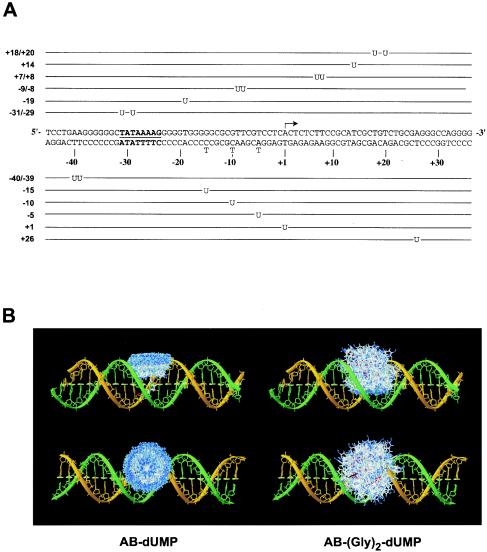

FIG. 1.

Photoprobes used for in-gel protein-DNA photo-cross-linking. (A) The 12 photoprobes used in our analysis are schematically shown. The position of the photonucleotide AB-dUMP or AB-(Gly)2-dUMP (U) along the adenovirus major late promoter is indicated (positions −15, −10, and −5) in each case and is used to name each photoprobe. Mutations (N to T) used in some of our photoprobes are indicated. The positions of the TATA element (underlined and boldface) and initiation site (arrow) are indicated. (B) Low-energy conformers of AB-dUMP and AB-(Gly)2-dUMP in the DNA major groove. Molecular simulation was used to predict the various possible conformers in each case. The photoreactive nitrene is shown in blue.

FIG. 2.

In-gel photo-cross-linking of the RNAP II preinitiation complex. (A) Schematic representation of the in-gel photo-cross-linking procedure. Preinitiation complexes were assembled by mixing each photoprobe with RNAP II and the general transcription factors. The TBP-IIB-IIF-RNAP II-IIE-promoter complex was electrophoresed in native polyacrylamide-N,N′-bisacryloylcystamine gels and irradiated with UV directly in the gels. Gel slices containing the cross-linked complexes were recovered, solubilized, and treated with nucleases. The resulting cross-linked products were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE. EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (B) Gel mobility shift experiments showing the various intermediate complexes assembled using subsets of the general initiation factors and RNAP II. The positions of the various complexes are shown.

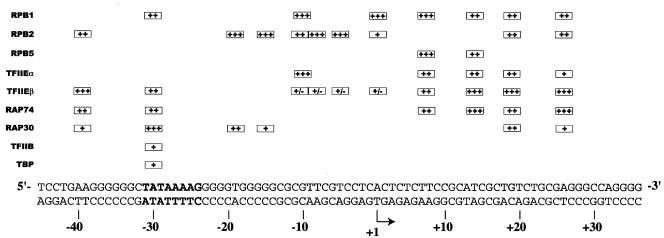

FIG. 3.

Summary of our in-gel photo-cross-linking results with a TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE-promoter complex. The boxes indicate the positions where each individual factor was found to cross-link to promoter DNA. +++, ++, and + represent the average relative intensities of the cross-linking signals obtained for each photoprobe using AB-dUMP. For example, the cross-linking of RPB2 at position −19 is more efficient than that of RAP30. The ± signs for the cross-linking of TFIIEβ to photoprobes −10, −9/−8, −5, and +1 indicate the uncertainty concerning their specificities, as nonspecific complexes made of multiple molecules of TFIIEβ were formed on these photoprobes in the absence of TBP (see the text for details). The use of AB-(Gly)2-dUTP in our photoprobes led to cross-linking results that are qualitatively similar to those using AB-dUTP. The positions of the TATA element (boldface) and initiation site (arrow) are indicated.

Our photo-cross-linking experiments used two different photoreactive nucleotides with side chains of various lengths, AB-dUMP (10.0 Å) and AB-(Gly)2-dUMP (18.6 Å). Both photoreactive nucleotides cross-linked the same set of polypeptides at all tested positions (Fig. 3 shows a summary). Molecular simulations indicated that the photoreactive nucleotides AB-dUMP and AB-(Gly)2-dUMP can adopt many different conformations as a result of the rotation of their aryl groups around the axes of some chemical bonds. The results of the simulations indicated that the reactive nitrene of AB-dUMP can probe an extensive space (∼20 by 20 by 10 Å) in the major groove of the DNA helix (Fig. 1B). The simulations also indicated that only a slightly larger space is probed by the nitrene of AB-(Gly)2-dUMP than by that of AB-dUMP. This result may explain the similarity of the cross-linking data obtained with both photonucleotides. The flexibility of both AB-dUMP and AB-(Gly)2-dUMP indicates that photoprobes containing a single photonucleotide could theoretically react with multiple polypeptides that approach the space occupied by the reactive nitrene. This situation is exacerbated for those photoprobes containing two photonucleotides.

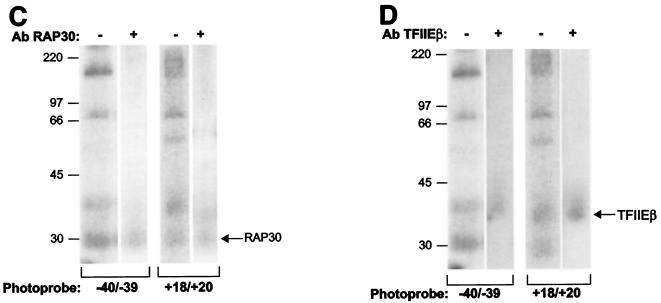

Promoter contacts by the RNAP II subunits RPB1, RPB2, and RPB5.

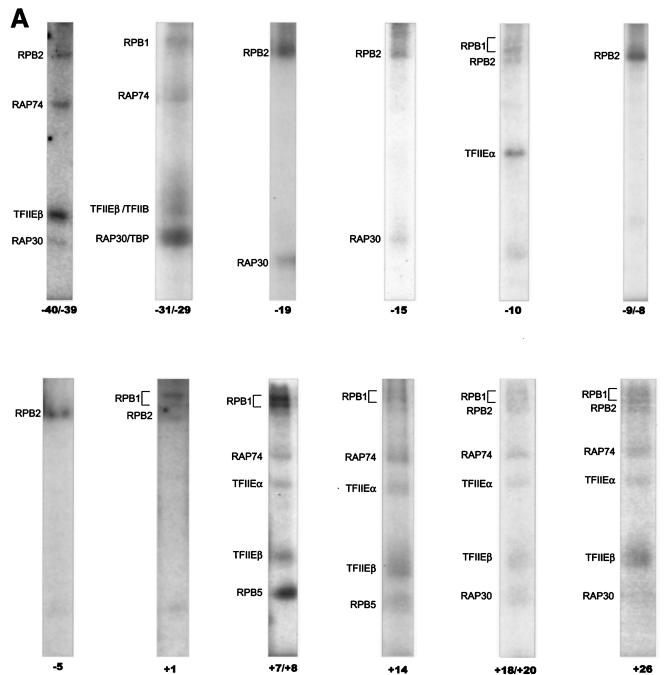

The in-gel site-specific protein-DNA photo-cross-linking results are summarized in Fig. 3, and some representative data are shown in Fig. 4. RPB1 cross-linked to seven positions from nt −31/−29 to +26, RPB2 cross-linked to nine positions from nt −40/−39 to +26, and RPB5 cross-linked to two positions from nt +7/+8 to +14 (Fig. 4B). Notably, RPB2 cross-linked to the promoter at six consecutive positions between −19 and +1, indicating that this promoter region closely approaches the second-largest RNAP II subunit. Between +7/+8 and +14, the promoter cross-linked to both RPB1 and RPB5, while further downstream, between +18/+20 and +26, cross-links were obtained with both RPB1 and RPB2. RPB1 cross-linked to the TATA box (−31/−29) and RPB2 upstream of TATA at −40/−39. The region between −10 and +1, where promoter melting occurs in the presence of TFIIH and hydrolyzable ATP, makes only seven cross-links with the TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE complex, four of which are with RPB2.

FIG. 4.

In-gel photo-cross-linking data. (A) Examples of the results obtained in our photo-cross-linking experiments with photoprobes prepared using AB-dUMP. The position of each cross-linked polypeptide is indicated. (B) Gel showing that the polypeptide that specifically cross-links at positions +7/+8 and +14 comigrates with the RPB5 subunit of RNAP II as identified using mass spectrometry. (C and D) RAP30 (C) and TFIIEβ (D) cross-link to photoprobes −40/−39 and +18/+20. The identities of the cross-linking bands were confirmed by immunoprecipitation of cross-linked polypeptides with antibodies (Ab) raised against RAP30 and TFIIEβ. +, present; −, absent.

Promoter contacts by TFIIF subunits.

Our results, shown in Fig. 3 and 4, reveal a limited number of cross-links by TFIIF subunits along promoter DNA. RAP74 strongly cross-linked to four positions between +7/+8 and +26 and cross-linked more weakly to TATA and upstream of it. RAP30 cross-linked to four positions between −40/−39 and −15. Surprisingly, additional cross-links by RAP30 were observed at positions +18/+20 and +26. The cross-linking of RAP30 to nt −40/−39 and +18/+20, two positions ∼60 bp apart, has been confirmed by immunoprecipitation of cross-linked RAP30 using an antibody directed against RAP30 (Fig. 4C). Our photo-cross-linking data for TFIIF subunits indicates that the location of RAP74 is centered downstream of +1 whereas that of RAP30 is centered on the TATA box and immediately downstream of it. Additional contacts by RAP74 upstream of TATA and by RAP30 downstream of +1 may be the result of tight bending and wrapping of the promoter DNA in the complex and/or of the presence of two RAP74-RAP30 dimers in the preinitiation complex (see Discussion).

Promoter contacts by TFIIE subunits.

The small subunit of TFIIE, TFIIEβ, cross-linked specifically to four positions downstream of +1 between +7/+8 and +26 and to two positions upstream of TATA between −40/−39 and −31/−29 (see below). The cross-linking of TFIIEβ to nt −40/−39 and +18/+20, two positions ∼60 bp apart, has been confirmed by immunoprecipitation of the cross-linked polypeptide using an antibody raised against TFIIEβ (Fig. 4D). Notably, TFIIEβ cross-linked to the same photoprobes as the RAP74 subunit of TFIIF, suggesting that these two subunits are closely positioned in the preinitiation complex. TFIIEα also cross-linked to the promoter downstream of +1 between +7/+8 and +26; the cross-link to +26 was weak. Notably, TFIIEα cross-linked to nucleotide −10. These results indicate that TFIIEα is the only general initiation factor that closely approaches the promoter in the region where DNA melting is to occur in the open complex.

We also obtained cross-linking of TFIIEβ to photoprobes −10, −9/−8, −5, and +1. However, and for a reason that remains to be determined, all four photoprobes supported the efficient formation of a low-mobility complex in the absence of TBP (data not shown). When these nonspecific complexes, assembled in the absence of TBP, were UV irradiated, gel purified, and processed through our cross-linking procedure, we obtained strong signals corresponding to TFIIEβ, as if these nonspecific complexes contained an aggregate made of multiple molecules of TFIIEβ. Because we obtained strong nonspecific cross-linking of TFIIEβ in the absence of TBP, we cannot be certain that the weak TFIIEβ cross-linking signals obtained in the presence of TBP at positions −10, −9/−8, −5, and +1 are specific. For this reason, the cross-linking of TFIIEβ between −10 and +1 is considered tentative (Fig. 3).

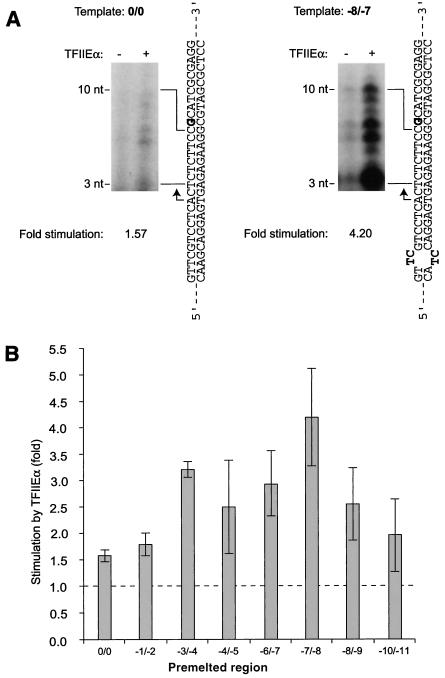

Role of TFIIEα in transcription initiation.

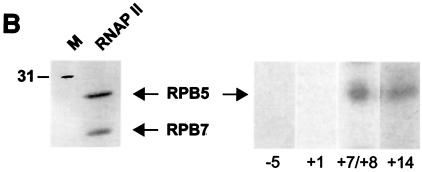

TFIIE has previously been shown to stimulate promoter melting in vitro (22, 23, 39). The cross-linking of TFIIEα to nucleotide −10 at the upstream end of the transcription bubble in the open complex supports this role. If the contact by TFIIEα at position −10 is important to promoter melting, we would predict that TFIIEα plays a key role during transcription initiation and affects transcription in vitro when using templates carrying short single-stranded (premelted) DNA regions. To test this hypothesis, we used an in vitro initiation assay that minimally requires the presence of TBP, TFIIB, TFIIF, and RNAP II (Fig. 5). A short double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the adenovirus major late promoter has been used as a template and was shown to support accurately initiated transcription in vitro (30). Compared to a reaction containing TBP, TFIIB, TFIIF, RNAP II, and TFIIEβ, the number of initiation events was slightly increased upon addition of TFIIEα (Fig. 5A, left). Notably, the presence of a 2-nt single-stranded DNA region at −8/−7 resulted in strong stimulation of initiation by TFIIEα (Fig. 5A, right). Alternating this premelted region between −11 and −1 revealed that maximal stimulation occurred in the upstream half of the region that was to form the transcription bubble prior to initiation and where TFIIEα cross-links to the promoter (Fig. 5B). These results support the notion that TFIIEα, which closely approaches promoter DNA at position −10, is important in that it stabilizes promoter melting and stimulates the initiation of transcription.

FIG. 5.

TFIIEα stimulates transcription initiation. (A) All double-stranded (0/0) and artificially premelted (−8/−7) DNA templates were used in an abortive initiation assay in either the presence (+) or the absence (−) of TFIIEα. The positions of the abortive transcripts are indicated (3 to 10 nt). Stimulation levels obtained through the addition of TFIIEα are indicated. The positions of the first G residue (boldface) and the initiation site (arrows) are indicated. (B) The position of the 2-bp premelted region along the promoter DNA influences the stimulation of transcription by TFIIEα. Templates lacking (0/0) or carrying (−1/−2, −3/−4, −4/−5, −6/−7, −7/−8, −8/−9, and −10/−11) a 2-nt premelted region were used. Stimulation by TFIIEα is indicated. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Our previous photo-cross-linking data, along with our electron microscopy studies, provided evidence to support promoter DNA bending and wrapping in the preinitiation complex (13, 45). This model has been supported by a variety of results from biochemical and structural analyses, both in prokaryotes and in eukaryotes (9, 42, 43, 55; see reference 5 for a review). Our previous photo-cross-linking studies were limited due to the fact that the protein-DNA complexes submitted to UV cross-linking had not been purified after assembly, leading to the possibility that intermediate subcomplexes could contribute to nonrelevant cross-links of some factors to promoter positions. To address this issue and with the goal of increasing the resolution of our topological analysis, we have developed a method allowing us to cross-link protein-DNA complexes after native gel purification of the relevant complexes. Overall, the results indicate that the use of the in-gel photo-cross-linking procedure (i) only slightly reduced the total number of promoter cross-links by the transcription machinery, especially those of TFIIF and TFIIE in the vicinity of the transcription initiation site, and (ii) allowed the cross-linking of TFIIEα in the absence of TFIIH (compare Fig. 3 with reference 8, Fig. 1). Because the TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE-promoter complex studied here was run through a gel prior to protein-DNA photo-cross-linking and because such a complex does not assemble in the absence of TBP (or when a photoprobe with a mutated TATA box is used; data not shown), we are confident that the nonspecific interactions are eliminated. Notably, the length of the promoter region that is contacted by RNAP II, TFIIF, and TFIIE also remains basically unchanged compared to our previous results. More specifically, RNAP II cross-links to the DNA from −40 to +26, a 66-bp region that corresponds to 225 Å of B-form DNA. This expanse is significantly larger than the largest span of RNAP II, which is ∼140 Å. Furthermore, as we observed in our previous experiments, RAP74, RAP30, and TFIIEβ come into close contact with the promoter both upstream of TATA and downstream of +1. Together, these results indicate that promoter DNA is wrapped in the preinitiation complex (Fig. 6 shows a model), fully supporting our previous conclusions.

In the model shown in Fig. 6, the trajectory of the promoter DNA has been drawn to best account for our in-gel cross-linking results. Because the TBP-TFIIB-TFIIF-RNAP II-TFIIE-promoter complex is likely to be an intermediate between RPc (closed complex) and RPo (open complex), we do not expect the promoter DNA to be fully melted in the −9-to-+2 region, with the template strand entering the active site of the enzyme. Open-complex formation, which is obtained in the presence of TFIIH and ATP, is expected to produce an important conformational change in the complex, bringing the template strand of the promoter deep into the active-site cleft. In our topological model, the downstream end of the promoter follows the channel between the two “jaws,” where it cross-links to RPB1, RPB2, and RPB5. Between +1 and −20, the DNA closely approaches RPB2 before making a right turn in the region of the TATA element, where TBP and TFIIB also cross-link weakly, to maintain close proximity to RPB1. Tight bending redirects the promoter toward a domain of RPB2 in the −40 region. Only this path of the promoter DNA can easily explain the various contacts observed by the RNAP II subunits. As shown in Fig. 6B, the deduced path of the promoter DNA produces a left-handed loop against the mobile clamp of RNAP II, suggesting a role for the clamp structure in preinitiation mechanisms. Such a left-handed wrapping around the clamp is expected to relax the DNA helix, as opposed to a right-handed wrapping that would induce compaction of the DNA helix. Relaxation of promoter DNA may play a role in producing a partial single-stranded DNA region necessary for the action of the single-stranded helicase of TFIIH during open-complex formation.

Cross-linking of TFIIF and TFIIE both upstream of the TATA element and downstream of the initiation site indicates that both factors are associated with the mobile clamp of RNAP II. Tight wrapping of the promoter DNA around the polymerase clamp may be responsible for contacts by these two factors to promoter positions >60 bp away from each other (e.g., simultaneous promoter contacts at positions −40 and +26). Alternatively, or additionally, the putative presence of two molecules of each subunit of both TFIIF and TFIIE may help to explain the distal promoter contacts. Both TFIIF and TFIIE were shown to exist as α2β2 heterotetramers in solution. In support of this idea that two dimers of TFIIF are associated within the preinitiation complex, we have recently purified an RNAP II-containing complex using TAP-tagged RAP30 that contains both a tagged and an endogenous RAP30 molecule (C. Jeronimo, M.-F. Langelier, M. Zeghouf, M. Cojocaru, D. Baali, D. Forget, S. Mnaimneh, A. P. Davierwala, J. Pootoolal, M. Chandy, V. Canadien, B. K. Beattie, D. P. Richards, J. L. Workman, J. R. Hughes, J. Greenblatt, and B. Coulombe, submitted for publication).

The cross-link of TFIIEα to nucleotide −10 is of interest. TFIIEα contains a DNA binding activity that has been anticipated as being important to promoter melting. The region carrying the DNA binding activity is homologous to region 2 of prokaryotic sigma factors (37). Notably, and in full support of our results, region 2 of σA was found to contact position −10 in the RNAP holoenzyme-promoter complex (33). Stimulation of transcription initiation by TFIIEα, a phenomenon that is enhanced when the promoter is artificially premelted in the upstream portion of the melted region of the open complex, suggests that the −10 contact by TFIIEα stabilizes promoter melting, thereby stimulating initiation. Taken together, our results provide novel insights into the fine molecular details of transcriptional initiation mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions. We thank Bryan Wilkes for his invaluable help in producing the model in Fig. 1B, Diane Bourque for artwork, and Julie Edwards for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank members of the laboratory of Yvan Guindon for help with chemical procedures.

This work is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. M.-F.L. and V.T. hold studentships from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec. B.C. is a senior scholar from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartholomew, B., G. A. Kassavetis, B. R. Braun, and E. P. Geiduschek. 1990. The subunit structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor IIIC probed with a novel photocrosslinking reagent. EMBO J. 9:2197-2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke, T. W., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1996. Drosophila TFIID binds to a conserved downstream basal promoter element that is present in many TATA-box-deficient promoters. Genes Dev. 10:711-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burley, S. K., and R. G. Roeder. 1996. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:769-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell, E. A., O. Muzzin, M. Chlenov, J. L. Sun, C. A. Olson, O. Weinman, M. L. Trester-Zedlitz, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol. Cell 9:527-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulombe, B., and Z. F. Burton. 1999. DNA bending and wrapping around RNA polymerase: a “revolutionary” model describing transcriptional mechanisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:457-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer, P., D. A. Bushnell, J. Fu, A. L. Gnatt, B. Maier-Davis, N. E. Thompson, R. R. Burgess, A. M. Edwards, P. R. David, and R. D. Kornberg. 2000. Architecture of RNA polymerase II and implications for the transcription mechanism. Science 288:640-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer, P., D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 2001. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science 292:1863-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douziech, M., F. Coin, J. M. Chipoulet, Y. Arai, Y. Ohkuma, J. M. Egly, and B. Coulombe. 2000. Mechanism of promoter melting by the xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group B helicase of transcription factor IIH revealed by protein-DNA photo-cross-linking. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8168-8177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dvir, A., J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 2001. Mechanism of transcription initiation and promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feaver, W. J., O. Gileadi, Y. Li, and R. D. Kornberg. 1991. CTD kinase associated with yeast RNA polymerase II initiation factor b. Cell 67:1223-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein, A., C. F. Kostrub, J. Li, D. P. Chavez, B. Q. Wang, S. M. Fang, J. Greenblatt, and Z. F. Burton. 1992. A cDNA encoding RAP74, a general initiation factor for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature 355:464-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forget, D., and B. Coulombe. 2003. Topology of the RNA polymerase II transcription initiation complex: site-specific protein-DNA photo-cross-linking of purified complexes. Methods Enzymol. 370: 701-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Forget, D., F. Robert, G. Grondin, Z. F. Burton, J. Greenblatt, and B. Coulombe. 1997. RAP74 induces promoter contacts by RNA polymerase II upstream and downstream of a DNA bend centered on the TATA box. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7150-7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu, J., A. L. Gnatt, D. A. Bushnell, G. J. Jensen, N. E. Thompson, R. R. Burgess, P. R. David, and R. D. Kornberg. 1999. Yeast RNA polymerase II at 5 Å resolution. Cell 98:799-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnatt, A. L., P. Cramer, J. Fu, D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 2001. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 Å resolution. Science 292:1876-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrich, J. A., and R. Tjian. 1994. Transcription factors IIE and IIH and ATP hydrolysis direct promoter clearance by RNA polymerase II. Cell 77:145-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guex, N., and M. C. Peitsch. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714-2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ha, I., W. S. Lane, and D. Reinberg. 1991. Cloning of a human gene encoding the general transcription initiation factor IIB. Nature 352:689-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hampsey, M. 1998. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:465-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodo, H. G., III, and S. P. Blatti. 1977. Purification using polyethylenimine precipitation and low molecular weight subunit analyses of calf thymus and wheat germ DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II. Biochemistry 16:2334-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holstege, F. C., U. Fiedler, and H. T. Timmers. 1997. Three transitions in the RNA polymerase II transcription complex during initiation. EMBO J. 16:7468-7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holstege, F. C., D. Tantin, M. Carey, P. C. van der Vliet, and H. T. Timmers. 1995. The requirement for the basal transcription factor IIE is determined by the helical stability of promoter DNA. EMBO J. 14:810-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holstege, F. C., P. C. van der Vliet, and H. T. Timmers. 1996. Opening of an RNA polymerase II promoter occurs in two distinct steps and requires the basal transcription factors IIE and IIH. EMBO J. 15:1666-1677. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humphrey, W., A. Dalke, and K. Schulten. 1996. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingles, C. J., M. Shales, W. D. Cress, S. J. Triezenberg, and J. Greenblatt. 1991. Reduced binding of TFIID to transcriptionally compromised mutants of VP16. Nature 351:588-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, Y., S. J. Triezenberg, and J. D. Gralla. 1994. Defective transcriptional activation by diverse VP16 mutants associated with a common inability to form open promoter complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 269:5505-5508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim, T. K., R. H. Ebright, and D. Reinberg. 2000. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science 288:1418-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, T. K., T. Lagrange, Y. H. Wang, J. D. Griffith, D. Reinberg, and R. H. Ebright. 1997. Trajectory of DNA in the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12268-12273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagrange, T., A. N. Kapanidis, H. Tang, D. Reinberg, and R. H. Ebright. 1998. New core promoter element in RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription: sequence-specific DNA binding by transcription factor IIB. Genes Dev. 12:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langelier, M. F., D. Forget, A. Rojas, Y. Porlier, Z. F. Burton, and B. Coulombe. 2001. Structural and functional interactions of transcription factor (TF) IIA with TFIIE and TFIIF in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38652-38657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu, H., O. Flores, R. Weinmann, and D. Reinberg. 1991. The nonphosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II preferentially associates with the preinitiation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:10004-10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreland, R. J., F. Tirode, Q. Yan, J. W. Conaway, J. M. Egly, and R. C. Conaway. 1999. A role for the TFIIH XPB DNA helicase in promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22127-22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murakami, K. S., S. Masuda, E. A. Campbell, O. Muzzin, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science 296:1285-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami, K. S., S. Masuda, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structural basis of transcription initiation: RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 4 Å resolution. Science 296:1280-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naryshkin, N., Y. Kim, Q. Dong, and R. H. Ebright. 2001. Site-specific protein-DNA photocrosslinking. Analysis of bacterial transcription initiation complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 148:337-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oelgeschlager, T., C. M. Chiang, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. Topology and reorganization of a human TFIID-promoter complex. Nature 382:735-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohkuma, Y., H. Sumimoto, A. Hoffmann, S. Shimasaki, M. Horikoshi, and R. G. Roeder. 1991. Structural motifs and potential sigma homologies in the large subunit of human general transcription factor TFIIE. Nature 354:398-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orphanides, G., T. Lagrange, and D. Reinberg. 1996. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 10:2657-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan, G., and J. Greenblatt. 1994. Initiation of transcription by RNA polymerase II is limited by melting of the promoter DNA in the region immediately upstream of the initiation site. J. Biol. Chem. 269:30101-30104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persinger, J., and B. Bartholomew. 2001. Site-directed DNA photoaffinity labeling of RNA polymerase III transcription complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 148:363-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson, M. G., J. Inostroza, M. E. Maxon, O. Flores, A. Admon, D. Reinberg, and R. Tjian. 1991. Structure and functional properties of human general transcription factor IIE. Nature 354:369-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivetti, C., S. Codeluppi, G. Dieci, and C. Bustamante. 2003. Visualizing RNA extrusion and DNA wrapping in transcription elongation complexes of bacterial and eukaryotic RNA polymerases. J. Mol. Biol. 326:1413-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rivetti, C., M. Guthold, and C. Bustamante. 1999. Wrapping of DNA around the E. coli RNA polymerase open promoter complex. EMBO J. 18:4464-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robert, F., and B. Coulombe. 2001. Use of site-specific protein-DNA photocrosslinking to analyze the molecular organization of the RNA polymerase II initiation complex. Methods Mol. Biol. 148:383-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robert, F., M. Douziech, D. Forget, J. M. Egly, J. Greenblatt, Z. F. Burton, and B. Coulombe. 1998. Wrapping of promoter DNA around the RNA polymerase II initiation complex induced by TFIIF. Mol. Cell 2:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roy, R., J. P. Adamczewski, T. Seroz, W. Vermeulen, J. P. Tassan, L. Schaeffer, E. A. Nigg, J. H. Hoeijmakers, and J. M. Egly. 1994. The MO15 cell cycle kinase is associated with the TFIIH transcription-DNA repair factor. Cell 79:1093-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaeffer, L., V. Moncollin, R. Roy, A. Staub, M. Mezzina, A. Sarasin, G. Weeda, J. H. Hoeijmakers, and J. M. Egly. 1994. The ERCC2/DNA repair protein is associated with the class II BTF2/TFIIH transcription factor. EMBO J. 13:2388-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaeffer, L., R. Roy, S. Humbert, V. Moncollin, W. Vermeulen, J. H. Hoeijmakers, P. Chambon, and J. M. Egly. 1993. DNA repair helicase: a component of BTF2 (TFIIH) basic transcription factor. Science 260:58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serizawa, H., R. C. Conaway, and J. W. Conaway. 1992. A carboxyl-terminal-domain kinase associated with RNA polymerase II transcription factor delta from rat liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7476-7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smale, S. T., and D. Baltimore. 1989. The “initiator” as a transcription control element. Cell 57:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spangler, L., X. Wang, J. W. Conaway, R. C. Conaway, and A. Dvir. 2001. TFIIH action in transcription initiation and promoter escape requires distinct regions of downstream promoter DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5544-5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sumimoto, H., Y. Ohkuma, E. Sinn, H. Kato, S. Shimasaki, M. Horikoshi, and R. G. Roeder. 1991. Conserved sequence motifs in the small subunit of human general transcription factor TFIIE. Nature 354:401-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timmers, H. T. 1994. Transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II does not require hydrolysis of the beta-gamma phosphoanhydride bond of ATP. EMBO J. 13:391-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tirode, F., D. Busso, F. Coin, and J. M. Egly. 1999. Reconstitution of the transcription factor TFIIH: assignment of functions for the three enzymatic subunits, XPB, XPD, and cdk7. Mol. Cell 3:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vassylyev, D. G., S. Sekine, O. Laptenko, J. Lee, M. N. Vassylyeva, S. Borukhov, and S. Yokoyama. 2002. Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature 417:712-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, Z., S. Buratowski, J. Q. Svejstrup, W. J. Feaver, X. Wu, R. D. Kornberg, T. F. Donahue, and E. C. Friedberg. 1995. The yeast TFB1 and SSL1 genes, which encode subunits of transcription factor IIH, are required for nucleotide excision repair and RNA polymerase II transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2288-2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan, M., and J. D. Gralla. 1997. Multiple ATP-dependent steps in RNA polymerase II promoter melting and initiation. EMBO J. 16:7457-7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young, R. A. 1991. RNA polymerase II. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 60:689-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, G., E. A. Campbell, L. Minakhin, C. Richter, K. Severinov, and S. A. Darst. 1999. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 Å resolution. Cell 98:811-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]