Abstract

Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia (CHH) is a rare congenital malformation characterized by marked unilateral overdevelopment of hard and soft tissues of the face. Asymmetry in CHH is usually evident at birth and accentuated with age, especially at puberty. The affected side grows at a rate proportional to the nonaffected side so that the disproportion is maintained thr oughout the life. Multisystem involvement has resulted in etiological heterogeneity including heredity, chromosomal abnormalities, atypical forms of twinning, altered intrauterine environment, and endocrine dysfunctions; however, no single theory explains the etiology adequately. Deformities of all tissues of face, including teeth and their related tissues in the jaw, are key findings for correct diagnosis of CHH. Here an attempt has been made to present a case of CHH with its archetypal features and to supplement existing clinical knowledge.

Keywords: Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia, facial asymmetry, hemifacial hypertrophy

Introduction

Asymmetry is one of the more unusual and interesting errors of human reproduction. Subtle, asymmetric variation of the contralateral structures of the head and face occur commonly in the general population in the absence of any local lesion or condition. Occasionally, a gross asymmetry easily perceptible to the eye may occur which progresses slowly but steadily and exhibits asymmetric development.[1,2] One such entity, characterized by marked unilateral overdevelopment of hard and soft tissues of the face is a rare congenital malformation. This has been termed variously in the literature as facial hemihypertrophy, hemimacrosomia, partial/unilateral gigantism, congenital hemifacial hyperplasia.[1–3] Pollock AR (1985) emphasized the use of the term congenital hemifacial hyperplasia because it is more histologically precise.[4]

Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia (CHH), first described by Meckel J F in 1882, did not gain widespread recognition until Gesell's classic studies.[1,5] Gessel (1927) described CHH as “essentially a developmental anomaly antedating birth and arising in a same way as a partial deflection of the normal process of birth.”[5] Ward and Lerner (1947) stated that “asymmetric enlargement could be manifested in a unilateral/crossed configuration and may involve all the body tissue in the area (ie, total) or a single systems such as muscular, vascular, skeletal or nervous (ie, limited).”[1] CHH has been classified by Rowe(1962) to involve:[6]

the entire half of the body: complex hemihypertrophy,

one or both limbs: simple hemihypertrophy,

the face, head and associated structures: hemifacial hypertrophy.

The purpose of this report is to present the case of a child with congenital hemifacial hyperplasia and to supplement existing clinical knowledge.

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy was referred to Government Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad (M.S.) with request for the treatment of facial asymmetry present since birth [Figure 1]. He was the last of three siblings without any previous family history of facial asymmetry. The mother neither had problems during pregnancy nor during delivery.

Figure 1.

Diffuse enlargement of the right side of face beginning abruptly at the midline and deviation of nose, mouth and chin toward the left side

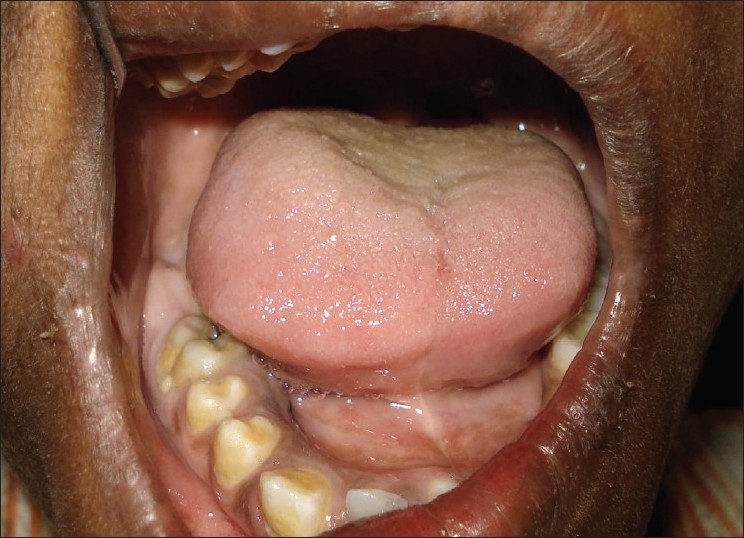

The physical examination revealed a mentally healthy and active boy. The patient's face was asymmetrical with an enlargement of the right side, including the malar, maxillary, and mandibular region. The pinna of the right ear was slightly enlarged and there was deviation of the nose and the chin to the left side, which appeared to be the normal side [Figure 1]. The skin and hairs appeared normal with the exception of small hyperpigmented nonhairy patches on the right cheek. The soft tissues of the right cheek and the lip were thick and fleshy. There was an obvious enlargement of tongue on the right side, which began abruptly at the midline [Figure 2]. Speech was not impaired by this deformity of the tongue and the sense of taste appeared to be equally distributed. The general examination revealed normal symmetrical development of the extremities and the trunk.

Figure 2.

Noticeable enlargement of tongue with the well-demarcated midline

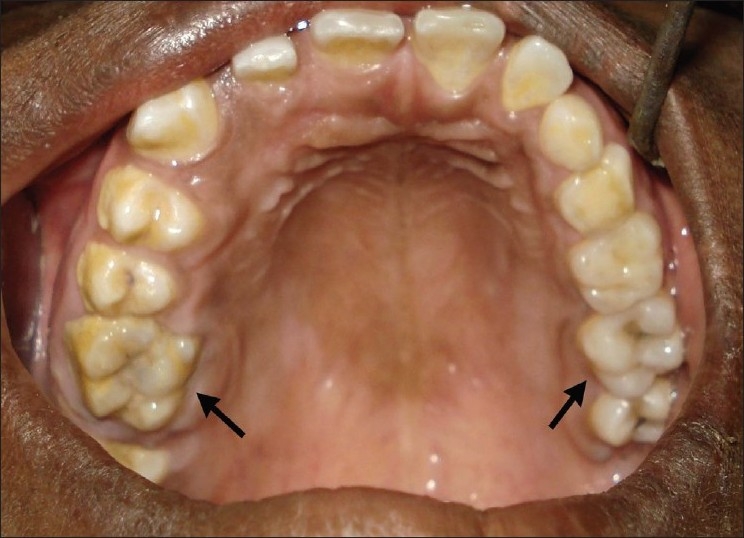

Erupted teeth in maxilla were 7,6,5,4,3,2,1/1,2,C,D,E,6,7 and in the mandible 7,6,5,4,3,2,1/1,2,3,4,E,6,7. The teeth on the affected side had matured earlier, were larger, and had erupted prematurely with early loss of the deciduous teeth followed by replacement of permanent dentition as compared to the normal side. It was clear that there was a unilateral enhancement of development on this side. The dimensions of right first molars were considerably greater than left first molars [Figure 3]. The tissue surrounding the teeth when compared with the left side was enlarged. This enlargement extended from the canine region being most prominent in the premolar and molar region [Figures 3 and 4]. Malocclusion was evident with an anterior open bite, distortion of dental arches, and spacing between teeth. The deviation to the left of the maxillary midline was noted.

Figure 3.

Obviously enlarged right first molar than left one with spacing between teeth on right side of the arch. Eruption pattern on right side is far advanced than the left side with broad and thick alveolar process

Figure 4.

Wider and thicker mandibular alveolar process on right side, particularly in the premolar-molar region

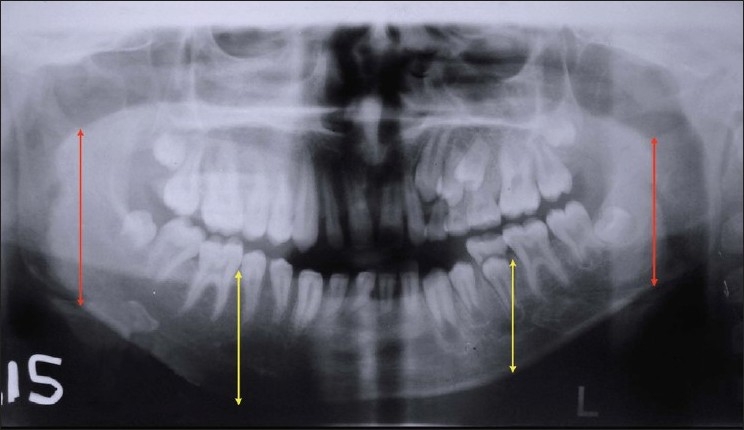

The eadiograph confirmed the clinical findings. OPG view showed that the mandible was unilaterally enlarged with the body of mandible being longer on the right side with an enlarged right condyle resulting in mandibular deviation to the left [Figure 5]. Other striking features were increased height of ramus and body of mandible on the right side than on the left. There was accelerated development of teeth on the right side with early eruption of permanents and closure of root apices than of the left-sided teeth [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Unilaterally enlarged ramus, body, and condyle of mandible on the right side. Accelerated development of teeth on the right side than on the left side

Discussion

Rowe (1962) described the criteria for true CHH as “it is an unusual condition that produces the facial asymmetry by a marked unilateral localized overgrowth of all the tissues in the affected area, that is, facial soft tissues, bone, and teeth.”.[1,6] The unilateral enlargement of the viscerocranium is bounded by frontal bone superiorly (not including eye), inferiorly by the border of mandible, medially by midline of the face, and laterally by ear, pinna being included within the hypertrophic area.[6] The disproportionate growth is almost always evident at birth and the enlarged side generally grows at the rate proportional to but slightly faster than the normal side. The disproportionate growth rate is maintained until the time of skeletal maturation and results in an asymmetry existing throughout life.[1]

The multisystem involvement has resulted in etiological heterogeneity and no single theory explains the etiology adequately. Factors that can be implicated are heredity, chromosomal abnormalities, atypical forms of twinning, altered intrauterine environment, endocrine dysfunctions, anatomical and functional anomalies of vascular/lymphatic systems and disturbances of the central nervous system.[1,7] An interesting concept put forth by Gesell (1927) suggests an inequality of regulatory abilities in embryologic development leading to an aberrant twinning mechanism.[5,7]

Pollock and coworkers (1985) proffer a hypothesis that the neural tube and its precursors are unilaterally hyperplastic.[4] The enlarged half of the neural tube would give rise to proportionally more numerous neural crest cells on the involved side. The increased number of crest cells persists throughout much of the prenatal and formative postnatal growth periods of life and lead to unilateral overgrowth of the crest-derived bone, cartilage, teeth, muscles, and soft tissue. Some tube segments may be involved more often than others helping explain why cephalic areas are more often affected clinically than other areas.[4,8]

Involvement of orofacial structures is related to asymmetric morphogenesis of teeth, bone, and soft tissues. Dentition abnormalities are with respect to crown size, root size, and shape and rate of development.[1,3] Tooth size enlargement is random with the frequency of involvement more in cuspid followed by premolars and first molars and least occurring in incisors, second molars, and third molars.[2,9] Usually enlargement does not exceed 50% of the normal size.[9] Root size and shape may be proportionally enlarged. Precocious eruption of permanent teeth by up to 4–5 years is usually seen.[1] Skeletal findings may be in the form of an asymmetric growth of the frontal bone, maxilla, palate, mandible, or condyles. Abnormal occlusal relationships such as midline deviation, unequal occlusal plane level, open bite, and widely spaced teeth on the involved side have been reported.[1,9] Soft tissue abnormalities include thickened and enlarged anatomical tissues on involved side with the sharply demarcated midline. The tongue, which is commonly involved, may show a bizarre picture of enlargement of fungiform papillae with unilateral enlargement and contralateral displacement.[2,3,9] Other soft tissues such as lips, buccal mucosa, uvula, and tonsils are also affected.

Because most of the striking signs of congenital hemihypertrophy are usually manifested in the orofacial region, Gorlin and Meskin (1962) suggested them help in differentiation of this condition from other entities that may simulate hypertrophy.[9] Among the conditions that closely mimic CHH as suggested by various authors are fibrous dysplasia, dyschondroplasia, congenital lymphedema, arteriovenous aneurysm, hemangioma, lymphangioma, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis, malignant conditions such as osteosarocma and chondrosarcoma.[2,7,9,10] All these conditions, however, exhibit sufficient clinical differences with CHH and should be distinguished on the basis of specific radiographs, clinical and laboratory findings.[3] To the unfamiliar clinician, hemihypertrophy that is localized to orofacial region can constitute a diagnostic problem. Deformities of the teeth and their related hard tissues in the jaw are key findings for correct diagnosis, particularly in hemihypertrophy limited to the face.[3,9,10]

Generally, treatment is not indicated for CHH unless cosmetic considerations are involved. Procedures usually are planned when physiological growth ceases. These may include reconstructive procedures such as osteotomies or orthognathic surgical procedure and soft tissue debulking by excision of excess masticatory and subcutaneous tissues, with preservation of neuromuscular functions.[2,3,7] CHH is generally associated with good prognosis. An extensive search of the English language literature revealed no formal reports of malignant transformation.[2]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Nayak R, Baliga MS. Crossed hemifacial hyperplasia: A diagnostic dilemma. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25:39–42. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.31989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam MN, Bhattacharya I, Ojha J, Bober K, Cohen DM, Green JG. Comparison between true and partial hemifacial hypertrophy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:501–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanna JN, Andrade NN. Hemifacial hypertrophy: Report of two cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;18:294–7. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(89)80098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollock RA, Newman MH, Burdi AR, Condit DP. Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia: An embryonic hypothesis and case report. Cleft palate J. 1985;22:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gessel A. Hemihypertrophy and twinning. Am J Med Sci. 1927;173:542. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowe NH. Hemifacial hypertrophy: Review of literature and addition of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15:572–87. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90177-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horswell BB, Holmes AD, Barnett JS, Hookey SR. Primary hemihypertrophy of the face: Review and report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:217–22. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tommasi AF, Jitomirski F. Crossed congenital hemifacial hyperplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:190–2. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawoyin JO, Daramola JO, Lawoyin DO. Congenital hemifacial hypertrophy: Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:27–30. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoniades K, Letsis I, Karakasis D. Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:344–8. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]