Abstract

Primary graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is a life-threatening complication. A shortened conditioning regimen may reduce the risk of infection and increase the chance of survival. Here, we report the outcome of 11 patients with hematologic diseases (median age, 44; range, 25–67 years, 7 males) who received a 1-day reduced-intensity preparative regimen given as a re-transplantation for primary graft failure. The salvage regimen consisted of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, alemtuzumab, and total-body irradiation, all administered 1 day before re-transplantation. All patients received T-cell replete peripheral blood stem cells from the same or different haploidentical donor (n = 10) or from the same matched sibling donor (n = 1). Neutrophil counts promptly increased to >500/µL for 10 of the 11 patients at a median of 13 days. Of these, none developed Grade III/IV acute graft-versus-host disease. At present, 8 of the 11 patients are alive with a median follow-up of 11.2 months from re-transplantation and 5 of the 8 are in remission. In conclusion, this series suggests that our 1-day preparative regimen is feasible, leads to successful engraftment in a high proportion of patients, and is appropriate for patients requiring immediate re-transplantation after primary graft failure following reduced-intensity transplantation.

Keywords: allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, primary graft failure, re-transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Primary graft failure after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation is a life-threatening complication because patients are at a high risk of severe infection owing to prolonged neutropenia after the initial transplantation. Several risk factors for graft failure have been suggested: transplantation of inadequate stem cell doses,1 use of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-mismatched donors2–4 or cord blood units,5–7 viral infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6),8–10 use of a non-myeloablative or reduced-intensity conditioning regimen,11,12 and presence of donor-specific HLA antibody.13–15 Graft rejection due to the immune response of the recipient is a major mechanism underlying graft failure. In cases of known immune-associated graft rejection, it is thought that patients should again receive a preparative regimen to suppress the recipient-derived immune system before re-transplantation. However, the appropriate regimen for re-transplantation is currently unknown. Typical preparative regimens start about 5 days before transplantation, and further delay an already prolonged recovery period. A shortened conditioning regimen may reduce the risk of infection and increase the chance of survival. Here, we report on 11 patients with hematologic disease (median age, 44; range, 25–67 years, 7 males and 4 females) who received a 1-day reduced-intensity preparative regimen and re-transplantation after primary graft failure following mainly reduced-intensity transplantation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The retrospective study population comprised all of the 11 adult patients who received a 1-day reduced-intensity preparative regimen and subsequent re-transplantation for primary graft failure at Duke Medical Center from May 2008 to August 2010. The characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 44 (range, 25–67) years. The patients had the following hematologic diseases: 5 had acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and were in complete remission, 1 had chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in the chronic phase, 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and was in partial remission, 2 had myelofibrosis (MF) and 1 had myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) without a history of cytotoxic chemotherapy, and 1 had severe aplastic anemia. The first donor was a haploidentical (n = 6) or matched sibling related donor (n = 1), matched unrelated donor (n = 2), or dual umbilical cord blood units (n = 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Case | Age | Sex | Disease | Disease status at transplant |

1st donor |

HLA matching at A, B, DR allele |

CD34 stem cell dose (× 106/kg) |

Preparative regimen for the 1st transplantation |

Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | F | MF | NR | MUD | 6/6 | 4.51 | Flu/Bus/ATG | Failed the 2nd transplantation from a Haplo donor after Flu/Cy/Alem |

| 2 | 42 | M | AML | CR3 | Haplo | 3/6 | 20.0 | Flu/Bus/Alem | |

| 3 | 44 | F | AML | CR2 | Haplo | 4/6 | 12.8 | Flu/Bus/Alem | |

| 4 | 56 | M | CLL | PR | Haplo | 3/6 | 7.16 | Flu/Mel/Alem | ADV infection when graft failed |

| 5 | 67 | M | MF | NT | MUD | 6/6 | 8.03 | Flu/Bus/Alem | |

| 6 | 61 | F | MDS | NT | Haplo | 3/6 | 22.92 | Flu/Bus/Alem | |

| 7 | 28 | M | CML | CP2 | DUCB | 4/6 + 4/6 | 0.09 +0.09 | Flu/TBI | |

| 8 | 52 | M | AML | CR2 | DUCB | 4/6 + 4/6 | 0.16 +0.17 | Flu/TBI | |

| 9 | 28 | M | AML | CR2 | Haplo | 3/6 | 10.9 | Flu/Bus/Alem | |

| 10 | 59 | F | AML | CR1 | Haplo | 4/6 | 19.17 | Flu/Bus/Alem | Residual AML clones detected |

| 11 | 25 | M | AA | NT | MSD | 6/6 | 16.07 | Flu/Cy/Alem |

F, female; M, male; MF, myelofibrosis; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; NR, non-remission; CR, complete remission; PR, partial response; NT, no prior cytotoxic treatment; MUD, matched unrelated donor; Haplo, haploidentical related donor; DUCB, dual umbilical cord blood; MSD, matched sibling donor; RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; Flu/Bus/ATG, fludarabine 160 mg/m2 + busulfan 520 mg/m2 + antithymocyte globulin 60 mg/kg; Flu/Bus/Alem, fludarabine 160 mg/m2 + busulfan 260 mg/m2 + alemtuzumab 80 mg; Flu/Mel/Alem, fludarabine 160mg/m2 + melphalan 140 mg/m2 + alemtuzumab 80 mg; Flu/TBI, fludarabine 160 mg/m2+ total-body irradiation 1350 cGy; Flu/Cy/Alem, fludarabine 120 mg/m2 + cyclophosphamide 2000 mg/m2 + alemtuzumab 100 mg; ADV, adenovirus.

Primary transplant regimen

Fludarabine (160 mg/m2) and alemtuzumab (80mg) with i.v. busulfan (260 mg/m2) or melphalan (140 mg/m2) was used as a reduced intensity regimen of T-cell replete peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies (n = 7), but antithymocyte globulin was used instead of alemtuzumab in one patient due to a physician’s preference. Fludarabine (120 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (2 g/m2) with alemtuzumab (100 mg) was used in transplantation for aplastic anemia (n = 1). Fludarabine (160 mg/m2) and total-body irradiation (TBI) (1350 cGy) was used as a myeloablative conditioning regimen for dual umbilical cord blood transplantation (n = 2) (Table 1).16

Salvage transplant regimen

The 1-day salvage regimen for graft failure rescue consisted of 30 mg/m2 fludarabine, 2 g/m2 cyclophosphamide, 20 mg alemtuzumab intravenously, and 200 cGy TBI, all administered 1 day before the transplantation (TBI was administered on the day prior for 2 patients, Cases 10 and 11, because of scheduling). Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells were collected from donors via apheresis and transplanted fresh without ex vivo T-cell depletion. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of 1000 mg mycophenolate mofetil either 2 (n = 5; Cases 1, 2, 5, 8, and 10) or 3 (n = 6; Cases 3, 4, 6, 7, and 11) times a day with cyclosporine (n = 10) or tacrolimus (n = 1, Case 7).

Assessment of engraftment and toxicity

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed 3–5 weeks after initial transplantation to assess donor-cell engraftment or to determine the cause for the delayed neutrophil recovery. Samples of bone marrow or peripheral blood were used to assess donor-cell chimerism after re-transplantation. PCR amplification and subsequent size comparison of multiple short tandem repeats was used to detect recipient and donor chimerism. Primary graft failure was defined as failure of neutrophil counts to exceed 500/µL or absence of donor-derived hematopoiesis (<5% donor cells). Toxicities were formally graded using National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 3.0). Acute and chronic GVHD were diagnosed and graded using traditional criteria.17,18

Statistical analysis

Patients’ data as of December 2010 were analyzed. The number of CD34+ cell counts in the first and second peripheral blood stem cell grafts was compared using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Overall survival was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods and STATA software version 11 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Patients and transplant characteristics

Although primary disease relapse and infections were extensively studied to determine the cause for primary graft failure, a definitive cause could not be determined for most of the patients (Table 1). The median number of CD34+ cells in peripheral blood stem cell grafts was 12.8 (range, 4.51–22.92) × 106/kg. One patient (Case 4) experienced engraftment failure likely related to adenovirus infection, diagnosed by real-time polymerase chain reaction quantitation of adenovirus in the plasma (34,440 DNA copies/mL), whereas another patient experienced failure owing to cytogenetic relapse of AML (Case 10). One patient (Case 1) received a second transplant from a haploidentical donor after a conditioning regimen consisting of alemtuzumab (20 mg/day from days −4 to 0), fludarabine (30 mg/m2 from days −5 to −2), and cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2 from days −5 to −2), but the engraftment failed.

The patients received grafts from haploidentical donors who were the same as (n = 5) or different from (n = 5) the initial donors or from the same matched sibling donor (n = 1) after the 1-day preparative regimen at a median of 35 (range, 30–91) days from the initial transplantation (Table 2). The median number of CD34+ cells transplanted was 12.1 (range, 8.0–20.0) × 106/kg. There was no statistical difference in CD34+ cell counts between the first and second peripheral blood stem cell grafts (P = 0.51). Neutrophil counts increased to >500/µL in 10 of the 11 patients with a median of 13 (range, 9–26) days, whereas a white blood cell (WBC) count of 500/µL and a neutrophil count of 325/µL with 80% chimerism of donor CD3+ and CD15+ cells were achieved in the remaining patient (Case 2); however, WBC gradually decreased to 0/µL without detection of any donor cell chimerism. This case was subsequently rescued by autologous stem cell transplantation. Among the 10 patients for whom neutrophil engraftment was achieved, donor chimerism was not analyzed in 2 patients (Cases 4 and 6) owing to deterioration of their clinical condition. One (Case 4) of the 2 patients died 13 days after re-transplantation from a progressive adenovirus infection that persisted before the start of the 1-day preparative regimen, whereas another patient (Case 6) died 26 days after re-transplantation secondary to multi-organ failure. Complete donor chimerism (>95%) was confirmed within 3 months for all the patients examined, except 1 (Case 10), who achieved 80% donor cell chimerism until 2 months after re-transplantation, when donor cell chimerism was gradually lost after a relapse of the primary disease. In 1 patient with initial engraftment (Case 11), donor T cell microchimerism decreased to 75% with a WBC count of 500/µL, a neutrophil count of 195/µL, and hypocellular marrow at 3 months. This patient achieved complete donor cell chimerism and stable engraftment after 2 Gy TBI and a subsequent boost of stem cells from the same donor.

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes after 1-day preparative regimen

| Case | Days from the 1st transplant |

Donor | HLA matching at A, B, DR allele |

Relation to the 1st donor |

CD34 stem cell dose (× 106/kg) |

Days until ANC >500 |

Engrafted | Acute GVHD |

Overall survival from the last SCT (month) |

Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 91 | Haplo | 3/6 | Different | 8 | 12 | Yes | 0 | Alive (30.0) | N.A. |

| 2 | 42 | Haplo | 3/6 | Same | 19.98 | Failure | No, rescued by auto | N.A. | Alive (22.4) | N.A. |

| 3 | 34 | Haplo | 4/6 | Same | 13.66 | 16 | Yes | (1) | Died (1.8) | MOF |

| 4 | 48 | Haplo | 3/6 | Different | 11.79 | 10 | Not tested | (0) | Died (0.4) | Infection |

| 5 | 35 | Haplo | 3/6 | Different | 14.94 | 14 | Yes | 0 | Alive (11.6) | N.A. |

| 6 | 30 | Haplo | 3/6 | Same | 13.27 | 26 | Not tested | (0) | Died (0.9) | MOF |

| 7 | 34 | Haplo | 3/6 | Different | 11.68 | 10 | Yes | 1 | Alive (4.2) | N.A. |

| 8 | 41 | Haplo | 3/6 | Different | Missing | 9 | Yes | 2 | Alive (6.8) | N.A. |

| 9 | 35 | Haplo | 3/6 | Same | 10.94 | 17 | Yes | 0 | Alive (10.7) | N.A. |

| 10 | 36 | Haplo | 4/6 | Same | 9.23 | 22 | Yes | 2 | Alive (4.2) | N.A. |

| 11 | 35 | MSD | 6/6 | Same | 12.42 | 12 | Initially Yes, but later required boost of CD34 after TBI 2 Gy | 0 | Alive (18.5) | N.A. |

Haplo, haploidentical related donor; MSD, matched sibling donor; TBI, total-body irradiation; N.A., not applicable; MOF, multi-organ failure.

Toxicities

This conditioning regime was well tolerated. None of the patients experienced severe nausea or emesis. Two patients (Cases 2 and 8) developed renal insufficiency ranging from creatinine 2.0 to 3.5 mg/dL 2 weeks after transplantation, but the value was almost normalized 1 month after transplantation (Table 3). Four patients (Cases 1, 2, 5, and 8) showed CMV reactivation, which were controllable by foscarnet treatment, and none developed CMV disease. Four patients (Cases 3, 6, 10, and 11) developed polyoma virus-related cystitis. Of these, 1 (Case 3) experienced urinary obstruction and subsequent multi-organ failure and died, and 1 (Case 6) experienced severe bladder pain requiring percutaneous nephrostomy. The latter patient (Case 6) also had multi-organ failure and died, which was possibly triggered by pulmonary complications with unknown etiology. Adenovirus infection progressed after re-transplantation in 1 patient (Case 4), leading to death. Other viral infections included those cause by HHV-6 in 2 subjects (Cases 2 and 8), influenza virus type A in 1 (Case 9), respiratory syncytial virus in 1 (Case 5), and herpes simplex virus in 2 patients (Cases 3 and 4). None developed documented bacterial or fungal infections.

Table 3.

Toxicities

| Toxicities | N | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | Renal insufficiency | 2 | Creatinine 2.0 to 3.5 mg/dL 2 weeks after SCT, but almost normalized 1 month after HCT |

| Infection | CMV reactivation | 4 | |

| Polyoma virus-related cystitis | 4 | 1 experienced renal insufficiency and 1 experienced urinary obstruction | |

| Adenovirus | 1 | ||

| HHV-6 | 2 | ||

| Influenza virus | 1 | ||

| RSV | 1 | ||

| HSV | 2 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HHV-6, human herpesvirus 6; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus, HSV, herpes simplex virus, HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Of the 8 individuals who achieved engraftment and survived >1 month, 2 developed Grade II acute GVHD, and 2 developed Grade I acute GVHD (Table 3). No patient developed Grade III or IV acute GVHD. One patient (Case 5) developed lung complications possibly caused by extensive chronic GVHD, and 3 patients (Cases 8, 10, and 11) developed limited chronic GVHD.

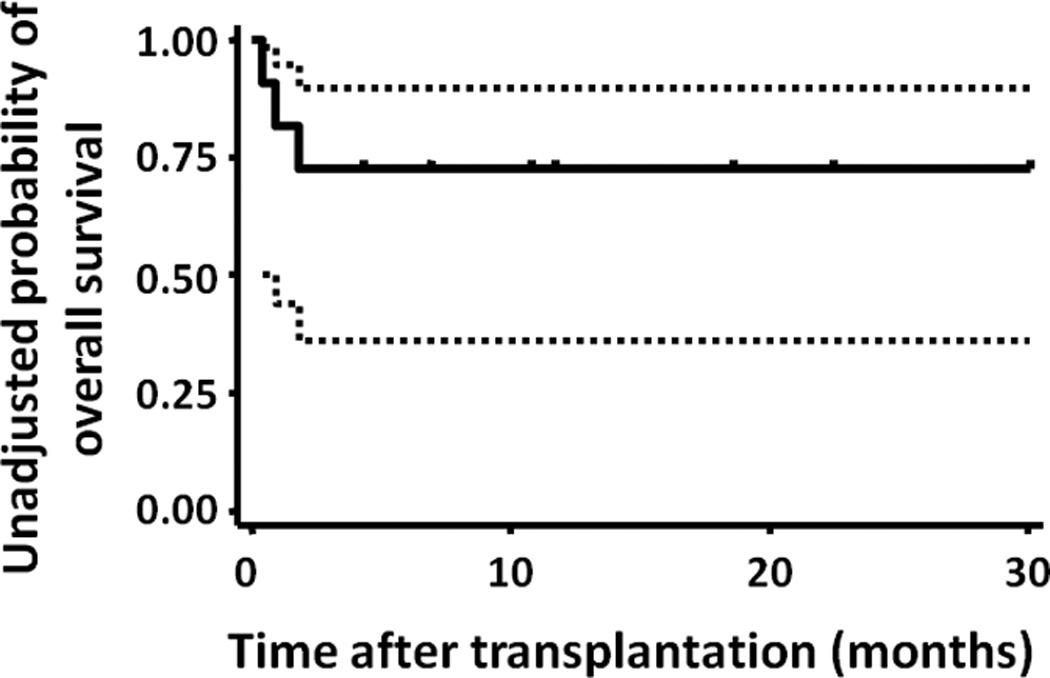

At present, 8 of the 11 patients survive with a median follow-up of 11.2 (range, 4.2–30.0) months from the 1-day preparative regimen and re-transplantation, and 5 of the 8 are in remission. The overall survival rate at 1 year was 0.73 (95% confidence interval, 0.37–0.90) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival.

The dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

We report 11 patients with primary graft failure who received a 1-day reduced-intensity preparative regimen and underwent subsequent re-transplantation using a T-cell replete peripheral blood stem cell graft, mainly from haploidentical donors. Neutrophil counts increased >500/µL in 10 of the 11 patients, and 7 of 8 evaluable patients achieved complete donor chimerism. No patients developed Grade III or IV acute GVHD. At present, 8 of the 11 patients are alive with a median follow-up of 11.2 (range, 4.2–30.0) months from re-transplantation. These findings suggest that the 1-day preparative regimen is an encouraging option for treatment of patients with graft failure following reduced-intensity transplantation.

We first developed the 1-day preparative regimen for initial transplantation from related haploidentical donors and reported neutrophil engraftment in 3 of 5 patients.19 To establish another regimen that potentially offered higher engraftment after haploidentical transplantation, we used a 5-day preparative regimen consisting of 100 mg alemtuzumab (20 mg/day from days −4 to 0), 120 mg/m2 fludarabine (30 mg/m2 from days −5 to −2), and 2000 mg/m2 cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2 from days −5 to −2) to intensify the immunosuppressive effects, and obtained an acceptable graft failure rate (primary graft failure, 6%; secondary graft failure, 8%) for haploidentical transplantation.20 This 5-day preparative regimen was also effective for re-transplantation after primary and secondary graft failure.21 However, this regimen requires more days from the graft failure diagnosis and re-transplantation decision to the day of re-transplantation; therefore, we employed the 1-day preparative regimen to treat patients with graft failure. In the condition in which the first preparative regimen might have already suppressed the recipient immune systems to some extent, the 1-day preparative regimen was effective and a high engraftment rate was achieved. This finding suggests that the 1-day preparative regimen, employed early in the recovery time course as soon as primary graft failure is identified, is a promising strategy for re-transplantation. However it should be noted that our salvage preparative regimen was shown to be safe and effective mainly in the primary graft failure following reduced-intensity conditioning regimen using alemtuzumab and salvage haploidentical transplantation. Therefore, further study is warranted to confirm our findings and extend the indication of our regimen to graft failure following myeloablative regimen or salvage transplantation from other stem cell sources.

Sumi et al.22 from Japan have employed our 1-day preparative regimen after modification (30 mg/m2 fludarabine for 1 to 3 days, 2 g/m2 cyclophosphamide, and 200 cGy TBI). They performed salvage single cord blood (n = 5) and matched sibling (n = 1) transplantation for patients with primary and secondary graft failure following single cord blood transplantation. All patients experienced successful engraftment, with neutrophil counts of >500/µL at a median of 24 (range, 18–26) day after the salvage cord blood transplantation, supporting the feasibility of the 1-day preparative regimen and successful engraftment in transplantation. The main difference from our salvage strategy is the omission of alemtuzumab from the conditioning regimen and the use of single cord blood unit. Alemtuzumab may not be required in the conditioning regimen for salvage single cord blood transplantation, based on the fact that the cord blood transplantation was being performed without in vivo T-cell depletion in many centers.7,16,23

For primary graft failure, immediate transplantation is essential because prolonged neutropenia exposes patients to infection-related death. Available related donors such as haploidentical donors are a suitable option because rapid neutrophil engraftment has been reported.2,20,24 Our earlier study showed that neutrophil engraftment was achieved at a median of 9 days.20 A shorter duration of neutropenia would greatly help reduce the risk of bacterial and fungal infections. In fact, successful re-transplantation by using a haploidentical donor after graft failure has been shown by several case studies.25–28 Furthermore, stem cell boosts with or without the use of a preparative regimen can be performed in cases of insufficient donor cell engraftment after re-transplantation. In our case, 1 patient who had initial engraftment after re-transplantation but gradually lost donor chimerism (donor T cell chimerism of 75% and hypocellular marrow of ≤5%) experienced successful engraftment after 200 cGy TBI and stem cell boosts from the same matched sibling donor. Although prompt engraftment can be achieved after haploidentical transplantation, one concern associated with haploidentical donors is the risk of developing severe acute GVHD.3,4 Interestingly, after our 1-day preparative regimen with only 20 mg of alemtuzumab and a GVHD prophylaxis consisting of mycophenolate mofetil and calcineurin inhibitors, no patients developed grade III or IV acute GVHD. This can be partially explained by the remaining alemtuzumab administered for the initial transplantation at the time of re-transplantation. Although we did not measure the concentration of alemtuzumab, Morris et al.29 examined 10 patients who received reduced-intensity conditioning consisting of 100 mg of alemtuzumab and reported that the concentration of alemtuzumab decreased to less than one-tenth of the peak level at day 28 after transplantation, but still remained at the lympholytic level of >0.5 µg/mL in 7 of the 10 patients. Therefore, administration of 20mg alemtuzumab may be adequate to suppress severe acute GVHD. Viral infection is a concern inherent to T-cell-depleted haploidentical transplantation.2–4 The development of modified donor T-cell infusions such as infusions of antigen-specific T-cells30,31 and donor T-cells depleted of CD8 T-cells or alloreactive T-cells32–34 could help improve immune recovery and clinical outcomes after transplantation.

Umbilical cord blood transplantation is another option for the treatment of graft failure because it can be rapidly performed if appropriate cord blood units are available. Recently, Waki et al.35 surveyed the data of 80 adult patients who received reduced-intensity cord blood transplantation for primary (n = 64) or secondary (n = 16) graft failure and reported that 45 (56%) of the 80 patients (74% of 61 patients who survived at least 28 days) achieved engraftment at a median of 3 weeks after re-transplantation. Although engraftment in cord blood transplantation is delayed as compared with that in haploidentical transplantation, cord blood units are a potential option for re-transplantation.

This shortened salvage regimen has another advantage. Often, there are cases of primary graft failure wherein the physicians and/or patients choose to wait for an additional few days to confirm graft failure and hesitate to start cytotoxic preparative regimen even though engraftment is unlikely. An abbreviated regimen made it possible to observe and wait until 1 day before the planned re-transplantation.

In conclusion, although the number of cases is small, this series suggests that our 1-day preparative regimen is feasible, leads to successful engraftment in a high proportion of patients, and is appropriate for patients requiring immediate re-transplantation. Since our salvage preparative regimen was shown to be safe and effective mainly in the primary graft failure following reduced-intensity conditioning, additional studies are warranted to confirm our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study investigators wish to thank the nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants, ward and clinic nurses, and staff of the Duke Adult Stem Cell Transplant Program for their outstanding care of the patients described in this report. J.K. is a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. This work is supported in part by a Scholar in Clinical Research award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (DAR), and NIH Grant P01-CA047741 (NJC).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Storb R, Prentice RL, Thomas ED. Marrow transplantation for treatment of aplastic anemia. An analysis of factors associated with graft rejection. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:61–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197701132960201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aversa F, Terenzi A, Tabilio A, Falzetti F, Carotti A, Ballanti S, et al. Full haplotype-mismatched hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase II study in patients with acute leukemia at high risk of relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3447–3454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koh LP, Rizzieri DA, Chao NJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant using mismatched/haploidentical donors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1249–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanda J, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA. Haploidentical transplantation for leukemia. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12:292–301. doi: 10.1007/s11912-010-0113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Wagner JE, Zhang MJ, Champlin RE, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2265–2275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha V, Labopin M, Sanz G, Arcese W, Schwerdtfeger R, Bosi A, et al. Transplants of umbilical-cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2276–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Nagamura-Inoue T, Taniguchi S, Takahashi S, Kai S, et al. Disease-specific analyses of unrelated cord blood transplantation compared with unrelated bone marrow transplantation in adult patients with acute leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:1631–1638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steffens HP, Podlech J, Kurz S, Angele P, Dreis D, Reddehase MJ. Cytomegalovirus inhibits the engraftment of donor bone marrow cells by downregulation of hemopoietin gene expression in recipient stroma. J Virol. 1998;72:5006–5015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5006-5015.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrigan DR, Knox KK. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) isolation from bone marrow: HHV-6-associated bone marrow suppression in bone marrow transplant patients. Blood. 1994;84:3307–3310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston RE, Geretti AM, Prentice HG, Clark AD, Wheeler AC, Potter M, et al. HHV-6-related secondary graft failure following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:1041–1043. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott BL, Sandmaier BM, Storer B, Maris MB, Sorror ML, Maloney DG, et al. Myeloablative vs nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia with multilineage dysplasia: a retrospective analysis. Leukemia. 2006;20:128–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Blanc K, Remberger M, Uzunel M, Mattsson J, Barkholt L, Ringden O. A comparison of nonmyeloablative and reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:1014–1020. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000129809.09718.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spellman S, Bray R, Rosen-Bronson S, Haagenson M, Klein J, Flesch S, et al. The detection of donor-directed, HLA-specific alloantibodies in recipients of unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation is predictive of graft failure. Blood. 2010;115:2704–2708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-244525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciurea SO, de Lima M, Cano P, Korbling M, Giralt S, Shpall EJ, et al. High risk of graft failure in patients with anti-HLA antibodies undergoing haploidentical stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1019–1024. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b9d710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takanashi M, Atsuta Y, Fujiwara K, Kodo H, Kai S, Sato H, et al. The impact of anti-HLA antibodies on unrelated cord blood transplantations. Blood. 2010;116:2839–2846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanda J, Rizzieri DA, Gasparetto C, Long GD, Chute JP, Sullivan KM, et al. Adult Dual Umbilical Cord Blood Transplantation Using Myeloablative Total Body Irradiation (1350 cGy) and Fludarabine Conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan KM, Agura E, Anasetti C, Appelbaum F, Badger C, Bearman S, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and other late complications of bone marrow transplantation. Semin Hematol. 1991;28:250–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goggins TF, Rizzieri DA, Prosnitz R, Gasparetto C, Long G, Horwitz M, et al. One day preparative regimen for allogeneic non-myeloablative stem cell transplantation (NMSCT) using 3–5/6 HLA matched related donors. Blood. 2003;102:476b–477b. (abstract 5633). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizzieri DA, Koh LP, Long GD, Gasparetto C, Sullivan KM, Horwitz M, et al. Partially matched, nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplantation: clinical outcomes and immune reconstitution. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:690–697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Byrne BJ, Horwitz M, Long GD, Gasparetto C, Sullivan KM, Chute J, et al. Outcomes of a second non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation following graft rejection. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41:39–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumi M, Shimizu I, Sato K, Ueki T, Akahane D, Ueno M, et al. Graft failure in cord blood transplantation successfully treated with short-term reduced-intensity conditioning regimen and second allogeneic transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2010;92:744–750. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauter C, Abboud M, Jia X, Heller G, Gonzales AM, Lubin M, et al. Serious Infection Risk and Immune Recovery after Double-Unit Cord Blood Transplantation Without Antithymocyte Globulin. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.001. e-pub ahead of print 1 March 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa H, Ikegame K, Yoshihara S, Kawakami M, Fujioka T, Masuda T, et al. Unmanipulated HLA 2–3 antigen-mismatched (haploidentical) stem cell transplantation using nonmyeloablative conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed N, Leung KS, Rosenblatt H, Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Myers GD, et al. Successful treatment of stem cell graft failure in pediatric patients using a submyeloablative regimen of campath-1H and fludarabine. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Matsubara H, Adachi S, Chang H, Fujino H, Higashi Y, et al. Second transplantation from HLA 2-loci-mismatched mother for graft failure due to hemophagocytic syndrome after cord blood transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2004;80:467–469. doi: 10.1532/ijh97.04063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dvorak CC, Gilman AL, Horn B, Cowan MJ. Primary graft failure after umbilical cord blood transplant rescued by parental haplocompatible stem cell transplantation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:300–303. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181914a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshihara S, Ikegame K, Taniguchi K, Kaida K, Kim EH, Nakata J, et al. Salvage haploidentical transplantation for graft failure using reduced-intensity conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.84. e-pub ahead of print 11 April 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris EC, Rebello P, Thomson KJ, Peggs KS, Kyriakou C, Goldstone AH, et al. Pharmacokinetics of alemtuzumab used for in vivo and in vitro T-cell depletion in allogeneic transplantations: relevance for early adoptive immunotherapy and infectious complications. Blood. 2003;102:404–406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cobbold M, Khan N, Pourgheysari B, Tauro S, McDonald D, Osman H, et al. Adoptive transfer of cytomegalovirus-specific CTL to stem cell transplant patients after selection by HLA-peptide tetramers. J Exp Med. 2005;202:379–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peggs KS, Verfuerth S, Pizzey A, Khan N, Guiver M, Moss PA, et al. Adoptive cellular therapy for early cytomegalovirus infection after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation with virus-specific T-cell lines. Lancet. 2003;362:1375–1377. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14634-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orti G, Lowdell M, Fielding A, Samuel E, Pang K, Kottaridis P, et al. Phase I study of high-stringency CD8 depletion of donor leukocyte infusions after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1312–1318. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bbf382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amrolia PJ, Muccioli-Casadei G, Huls H, Adams S, Durett A, Gee A, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy with allodepleted donor T-cells improves immune reconstitution after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:1797–1808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy DC, Lachance S, Kiss T, Cohen S, Busque L, Fish D, et al. Haploidentical stem cell transplantation: high doses of alloreactie-T cell depleted donor lymphocytes administered post-transplant decrease infections and improve survival without causing severe GVHD. Blood (ASH annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009;114:512. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waki F, Masuoka K, Fukuda T, Kanda Y, Nakamae M, Yakushijin K, et al. Feasibility of reduced-intensity cord blood transplantation as salvage therapy for graft failure: results of a nationwide survey of adult patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]