Abstract

Amphipathic polymers called amphipols (APols) have been developed as an alternative to detergents for stabilizing membrane proteins (MPs) in aqueous solutions. APols provide MPs with a particularly mild environment and, as a rule, keep them in a native and functional state for longer periods than detergents do. Amphipol A8-35, a derivative of polyacrylate, is widely used and has been particularly well studied experimentally. In aqueous solutions, A8-35 molecules self-assemble into well-defined globular particles, with a mass of ~40 kDa and a Rg of ~2.4 nm. As a first step towards describing MP/A8-35 complexes by molecular dynamics (MD), we present three sets of simulations of the pure APol particle. First, we performed a series of all-atom MD (AAMD) simulations of the particle in solution, starting from an arbitrary initial configuration. While AAMD simulations result in cohesive and stable particles over a 45-ns simulation, the equilibration of the particle organization is limited. This motivated the use of coarse-grained MD (CGMD), allowing us to investigate processes on the microsecond timescale, including de novo particle assembly. We present a detailed description of the parametrization of the CGMD model from the AAMD simulations, and a characterization of the resulting CGMD particles. Our third set of simulations utilizes reverse coarse-graining (rCG), through which we obtain all-atom coordinates from a CGMD simulation. This allows higher-resolution characterization of a configuration determined by a long-timescale simulation. An excellent agreement is observed between MD models and experimental, small angle neutron scattering data. The MD data provides new insights into the structure and dynamics of A8-35 particles, possibly relevant to the stabilizing effects of APols on MPs, as well as a starting point for modeling MP/A8-35 complexes.

Introduction

Studying membrane proteins (MPs) in vitro is a notoriously difficult task 1–4. The most common method of making MPs water-soluble is through the use of detergents 5. Detergents, by necessity, are dissociating: in order to solubilize MPs, they must disrupt interactions within the membrane 6, 7. However, they not only prevent protein aggregation and precipitation, but they also compete with the specific protein/protein and protein/lipid interactions that keep MPs in their native state. As a result, most MPs become unstable in detergent solutions. Stabilization can be achieved by transferring MPs, after solubilization, to less dissociative environments 6, 7, among which are specially designed amphipathic polymers called amphipols (APols) 7–11. APols strongly stabilize most MPs, through a combination of effects that includes an intrinsically weak dissociating power, the ability to work at low concentrations of free APols, and kinetic effects (for a discussion, see 11). APols have proven useful in a wide range of experimental circumstances, including folding MPs to their native state and synthesizing them in vitro, immobilizing them onto solid supports, and studying them by radiation scattering, light spectroscopy, NMR or cryo-electron microscopy. They also have important practical uses in drug screening, diagnostics, or vaccination (for a review, see ref 11). NMR studies show that MP/APol complexes can be used for obtaining high-resolution structures of MPs or their ligands 11–14.

Among several chemically different types of APols whose usefulness for handling MPs in vitro has been documented (for an overview see 11), the most thoroughly used APol to date is A8-35 8, 15. In this nomenclature, the ‘A’ refers to the polyacrylate backbone, chosen because it is highly flexible and allows the polymer to adapt to the small radius of curvature and irregularities of MP transmembrane domains 9. The 8 refers to the initial estimates of the average molecular mass (~8 kDa, but see below) of single polymer chains after derivation with two grafts, octylamine and isopropylamine, at ratios of 35% ungrafted carboxylates, 40% isopropylamine, and 25% octylamine (Figure 1) 8, 9. Derivation with isopropylamine, which reduces the number of free carboxylates, decreases the charge density along the chain 9. The proportion of octylamine was adjusted so that the polymer remain highly soluble in water while becoming sufficiently amphipathic to adsorb onto the hydrophobic transmembrane surfaces of MPs 9, 11, 13, 14, forming water-soluble complexes. In aqueous solution, A8-35 has been shown to self-assemble into well-defined globular particles, with a mass of ~40 kDa and a radius of gyration (Rg) of ~2.4 ± 0.2 nm, similar to detergent micelles 16. Each particle comprises an average of ~80 octylamine chains, which are thought to form a hydrophobic core 16. While the composition, size and solution properties of A8-35 particles have been extensively characterized experimentally 16–18, little is known about their internal organization nor their dynamics, two features thought to be relevant to the mechanism(s) by which A8-35 stabilizes MPs and favors their folding 9, 11, 19–21. In the present work, we have investigated these issues using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

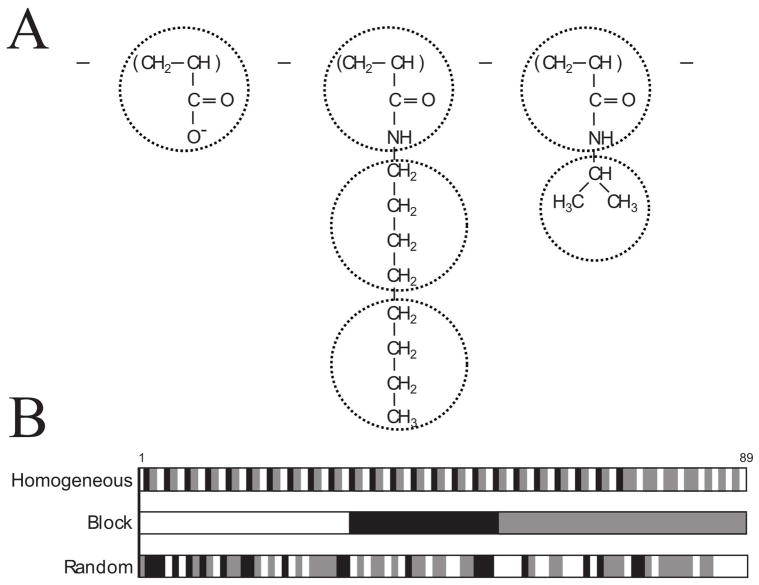

Figure 1.

A) Chemical Structure of the ungrafted, octylamine grafted, and isopropylamine grafted units, with the coarse-grained mapping. B) Grafting sequences simulated (white = ungrafted, black = octylamine grafted, gray = isopropylamine grafted).

In order to model A8-35 particles, we have utilized all-atom (AA) and coarse-grained (CG) MD simulations. AAMD simulation has proven to be a useful tool for studying the structure and dynamics of soluble proteins 22–24, lipid bilayers 25–28, MPs 29–31, and polymers 32–36. However, the computational expense of explicitly representing every atom of the solute and solvent limits AAMD simulations to a timescale of tens of nanoseconds. In order to overcome this limitation, CGMD force fields have been developed, in which groups of atoms are represented by a single CGMD “bead.” In particular, the MARTINI CGMD force field 37 has been used to study the microsecond time-scale behavior of many molecules, including lipids 37, 38, MPs 39, and polymers 34, 35, 40–42. Also of particular relevance are recent studies which have used CGMD and AAMD to study the structure of discoidal lipoprotein assemblies, which are another potential alternative to detergents for MP stabilization 7, 43, 44.

Our multi-scale strategy is summarized in Figure 2: we first present AAMD simulations of multiple A8-35 particles starting from arbitrary initial configurations. We then use the results of these simulations to parametrize a CGMD model. Using the CGMD model we are able to obtain 4 microseconds of simulation time and thus directly observe de novo the assembly of four polymer chains into a single particle. Finally, we present a third set of simulations, where we convert a set of coordinates obtained from the CGMD simulations into the AAMD resolution. This process of reverse coarse-graining (rCG) allows us to characterize the structures obtained from a multi-microsecond CGMD simulation using higher resolution AAMD simulations. For each of these three sets of simulations, we characterize the structure of the particles, emphasizing the extent to which the particles form a hydrophobic core, a critically important feature for the colloidal stabilization of hydrophobic MPs. These results represent a first step towards an all-atom MD study of MP/APol complexes. They also offer insights into possible mechanisms of stabilization of MPs by APols.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the multi-scale strategy employed in the present study. First, AAMD simulations are executed and analyzed. Second, the results from the AAMD simulations are used to parametrize a CGMD model. Third, coordinates from CGMD simulations are then used to start rCG (all-atom) simulations, allowing higher resolution characterization of equiilbrated particles.

Methods

AAMD Simulation Setup

Most of the bonded and non-bonded parameters for the AAMD model were adapted from functional groups that have been previously parametrized in the CHARMM22 force field 45. Based on the CHARMM atom typing scheme, Lennard-Jones parameters and partial charges are available in the CHARMM22 force field for all atoms in the amphipol molecule. Similarly, most of the bonded terms including bond lengths, angles, and proper and improper dihedral angles can be directly transferred from other molecules in the CHARMM22 force field without further optimization. However, the C-Cα-C angle, where Cα is the backbone carbon connected to the side chain graft, required an angle parameter that did not exist in the CHARMM22 force field. To parametrize the angle term for a 3 atom sequence of CHARMM atom types CT2-CT1-CT2, we chose N-metyl-3-ethylbutamide as the model compound and used the angle bending parameters for alkanes (CT2-CT1-CT1) in the CHARMM22 force field as initial input. AAMD parameters were determined to reproduce the geometries of the model compound from optimizations using hybrid density functional theory at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level 46. In the CHARMM force field the bending potential for this angle is the sum of a harmonic potential and a Urey-Bradley term to restrain the distance between the first and third atoms in the angle:

| (1) |

For the CT2-CT1-CT2 angle, we found that the optimized parameters are Kangle=53.350 kcal/mol/rad2, θAngle=114.000°, KUB=8.000 kcal/mol/Å2, RUB=2.561 Å. The predicted C-Cα-C angle with the optimized parameters is 111.61°, which is in excellent agreement with the value of 111.62° obtained from the B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculation.

Each AAMD system was built with four polymer chains consisting of 89 units each, with charges neutralized by the addition of sodium ions, and solvated in a cubic box of water represented by the TIP3P model 47, large enough to avoid self-interaction through the periodic boundaries (89 Å × 89 Å × 89 Å). A length of 89 units was chosen based on a 10 kDa chain 8, 18, without attributing any of the mass to sodium ions. As we discuss below, a series of simulations were performed in order to show that our assumed chain length has no significant effect on the particle properties. Systems were built using the CHARMM molecular mechanics package 48 and AAMD simulations were run using the NAMD molecular dynamics package 49, using the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble with a total of ~70,000 atoms, a constant pressure of 1 atm, and a constant temperature of 303 K. The temperature and pressure was controlled using the Langevin piston Nose-Hoover method 50. A cut-off of 10 Å was used with a switching function for van der Waals interactions and particle mesh Ewald summation was used to treat long range electrostatic interactions 51. All bonds involving hydrogen were fixed using the SHAKE algorithm 52. A time-step of 2 fs was used and a total simulation time of 45 ns was run for each simulation.

Three sequences were simulated, presented schematically in Figure 1B. The first sequence, which we will refer to as ‘Homogeneous’, primarily contains an alternating sequence of ungrafted-octylamine-isopropylamine, though the sequence is not perfectly homogeneous due to the unequal proportions of the three components. We hypothesized that this sequence would show the least aggregation of octylamine grafts. The ‘Block’ sequence, is a triblock copolymer, designed to have a maximal ability to sequester octylamine grafts. Finally, a random sequence, was generated to investigate an intermediate degree of octylamine sequestering and to model a sequence that may be more representative of those formed by statistical polymerization, as actually used in the synthesis of A8-35.

CGMD Parametrization

As illustrated schematically in Figure 2, we have used our AAMD simulations to parametrize a CGMD model. While it is a common strategy to parametrize a CGMD model from AAMD simulations, numerous procedures have been used, even within the MARTINI CGMD force field 34, 35, 37, 39, 41, 42, 53–56. We followed closely the method used recently in the parametrization of carbohydrates 53.

To obtain non-bonded parameters, we created a CGMD molecule for which the water/octanol partitioning coefficient matches that calculated from the AAMD model. This is done by determining the free energy of solvation for the polymer in the two distinct solvents (water and water saturated octanol), obtaining ΔGW and ΔGO, the difference of which is ΔΔGOW. This relates to the partitioning coefficient (POW) by:

| (2) |

where R is the universal gas constant and T is temperature. Calculation of ΔGW and ΔGO is done using thermodynamic integration 57, where the potential energy describing the solute-solvent interaction (U) is scaled by a coupling parameter λ. When λ =0 there is no interaction (or the solute is a “dummy” molecule) and when λ =1 the solute-solvent interaction is fully occurring. By simulating the entire range of λ values between 0 and 1, a change in free energy can be calculated.

| (3) |

This change in free energy can then be related to the solvation energy (ΔGW or ΔGO) by defining a thermodynamic cycle (Figure S1).

Our strategy is to use thermodynamic integration to calculate POW from the AAMD representation and then design the CGMD molecule such that its POW matches the AAMD result. In the MARTINI force field there is only one particle type representing charged particles (Q), and thus the particle type of the ungrafted unit is assigned without calculation (specifically to the Qa subtype due to the presence of a hydrogen bond acceptor). However, for uncharged particles, there is a gradient of 11 particle types, ranging from hydrophobic to polar, making the assignment through a quantitative comparison between the AAMD and CGMD representations preferable. Partition coefficients were calculated for a single unit, with either the octylamine or isopropylamine grafting. In the AAMD simulations, 25λ values were simulated for 100 ps each (using a 1 fs time-step and totaling 2.5 ns per simulation and 15 ns altogether). The solvents consisted of either ~3,880 waters or 183 octanols and 67 waters (an octanol:water ratio similar to that used previously for this type of calculation 53, 58). In the CGMD simulations, 21λ values were executed for 50 ns each (a total of ~1 μs per simulation and ~80 μs total). The solvents consisted of 2,049 water beads or 519 octanols and 43 water beads 53. Note that in the MARTINI force field, each water bead represents 4 water molecules 37. CGMD simulations were run using GROMACS molecular dynamics package as described below 59.

Bonded Parameters were obtained by comparison with the AAMD simulations of the A8-35 particle. The CGMD bond distances, angles, and dihedrals are taken from the AAMD simulation, by calculating the distances, angles, and dihedrals formed by the center of mass of the atoms mapped to the CGMD beads. In the CGMD force field, bond lengths are defined by a harmonic potential:

| (4) |

with an equilibrium distance RBond and force constant KBond. In the MARTINI force field, angles are typically defined using a cosine-harmonic potential:

| (5) |

All angles described below are parametrized using the form of Eq 5, with the exception of the angle defined by three consecutive backbone beads, for which we have found greater stability using a harmonic potential, similar to a recent polymer parametrization 34. The form of this potential is the same as Eq 1, but without the Urey-Bradley correction. Proper dihedral angles have a multiplicity of 1 and are defined as follows:

| (6) |

In order to assess the agreement between probability density functions representing the distribution of bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals in both representations, we quantify the intersection between the two distributions by:

| (7) |

where s represents the degree of overlap ranging from 0 (no overlap between these distributions) to 1 (complete overlap). Maximizing s results in a parameter for which the two representations have the greatest geometrical similarity. The final set of CGMD parameters and supporting files will be available through the MARTINI website (http://cgmartini.nl).

CGMD Simulations

Each CGMD simulation was initiated with four polymer chains in an entirely linear, extended conformation, separated from each other by at least 3 nm. The polymers were solvated in a box containing about 27,500 water beads and neutralizing sodium ions. CGMD simulations were run using the GROMACS molecular dynamics package 59, and the NPT ensemble was used with a pressure of 1 atm and a temperature of 303 K. Pressure was controlled using the Berendsen isotropic pressure coupling scheme. We note that our simulations at the AAMD and CGMD levels use different temperature/pressure coupling schemes, and though one recent study found no significant different between lipid bilayers simulated using different coupling schemes 60, this is a potential source of inconsistency. A time-step of 30 fs was used and a total simulation time of 4000 ns was run for each simulation. Each sequence was simulated three times using the same initial starting configuration and alternate starting velocities.

Reverse Coarse-Graining

Our strategy for obtaining an AAMD representation from a polymer CGMD coordinate set is similar to the method described previously for the reverse coarse-graining (rCG) of lipid bilayers 61. The coordinates of each polymer CGMD bead are mapped to a single atom and the remaining atoms are assigned coordinates according to standard geometries using CHARMM around these mapped atoms. As in our previous work, water and ions are not included in the reverse coarse-graining process, and the polymer is instead placed in a pre-equilibrated TIP3P waterbox 61. An initial molecular dynamics simulation of ~15 ns was executed to equilibrate the solvent configurations, during which the polymer atomic positions were restrained harmonically. Simulations were then run for 45 ns of unrestrained dynamics.

Analysis

The program CRYSON was utilized to calculate the small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) profiles from the atomic coordinates of each AAMD and rCG amphipol system 62. The simulated scattering profile was normalized according to the experimental intensities 16. The Guinier approximation 63 was used to calculate the radius of gyration (Rg) from the simulated SANS:

| (8) |

The Rg is obtained by plotting the scattering profile as a function of Q2, in which case the slope of the linear fit within the low Q region is equal to 1/3*Rg2.

The shape of the particles is described by determining the three principal axes of inertia, I1 > I2 > I3, and then finding the semi-axes of the ellipsoid (a, b, c) which has the same principal axes of inertia:

| (9) |

where M is the total mass of the particle. In the results, we present the a/c ratio, where a value of 1 indicates a sphere and larger values indicate increasing degrees of elongation. Analyses were performed using CHARMM 45, GROMACS 59, and a set of in-house Perl scripts. Visualization was performed using VMD 64.

Results

CGMD Parametrization

The first step in the parametrizing a CGMD representation of a molecule is mapping the AAMD structure to a discrete number of CGMD beads. In the MARTINI force field each bead is typically composed of about four non-hydrogen atoms 37. The ungrafted unit contains 5 non-hydrogen atoms, and is mapped to a single bead (Fig 1A). The isopropylamine grafted unit is split into a backbone (BB) and a side chain (SC), while the octylamine grafted unit is split into a backbone (BB) and two side chain beads (SC1 and SC2), as shown in Figure 1A. This mapping strategy results in an uneven distribution of atoms in the isopropylamine grafted unit (5 atoms assigned to the backbone and 3 to the side chain). However, it possesses two advantages: 1) It allows us to assign the same atoms to the backbone for both grafts and 2) It creates a molecule with a polar backbone and hydrophobic grafting, instead of two beads which are intermediately polar, better representing the fundamental features of the molecule.

In the MARTINI force field, non-bonded parameters are determined by the bead type. For example, two hydrophobic beads will have a favorable Lennard-Jones interaction, while a hydrophobic bead and hydrophilic bead will have an unfavorable interaction. Assigning non-bonded parameters to the ungrafted unit is trivial; beads containing a charge are of the ‘Q’ category, and the presence of a hydrogen bond acceptor indicates the Qa subtype 37. However, for charge-neutral beads there is a range of 11 possible bead types ranging from most hydrophobic (C1) to most polar (P5). Therefore, in order to assign the bead types and (thus the non-bonded interactions), we make use of the oil/water partitioning; an important feature for a polymer designed to adsorb onto hydrophobic proteins. Calculating the oil/water partitioning is done through a series of thermodynamic integration calculations which allow us to determine the solvation free energy in octanol and water (see Methods for more information). The difference in these solvation energies (Δ ΔGOW) for the AAMD representation is −0.5 kcal/mol for the isopropylamine grafted unit and −5.7 kcal/mol for the octylamine grafted unit. These differences in free energy correspond to logPOW values of 0.37 and 4.12 (Eq 2).

The next step is to create CGMD molecules which have logPOW values equal to the logPOW values of the AAMD representation. Table 1 presents logPOW values for several combinations of bead types for the backbone (BB) and isopropylamine side chain (SC). In bold is the combination we have chosen for the CGMD model, containing a backbone of type P3 and side chain of type C4. The agreement between the CGMD logPOW (0.43) and AAMD logPOW (0.37) is excellent relative to a recent CGMD parametrization 53. Additionally, intuitive comparison to other molecules parametrized in the MARTINI force field suggests that P3 and C4 are appropriate bead types for these molecules 37.

Table 1.

Log POW values for the isopropylamine grafted unit from CGMD simulations. Log POW value from AAMD is 0.37.

| Side chain | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | |||||

| C5 | 3.92 | ||||

| NDA | 3.00 | ||||

| P1 | 2.18 | 2.07 | 1.51 | 0.92 | |

| P2 | 1.90 | 1.55 | 1.24 | ||

| P3 | 1.09 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.43 | −0.14 |

| P4 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 0.25 |

Table 2 presents the logPOW values for several combinations of bead types for the BB and first side chain (SC1) of the octylamine graft, with the second side chain (SC2) set to type C1. A linear alkyl group consisting of four carbons should be the most hydrophobic type (C1), and therefore we expect both SC1 and SC2 to be type C1. The BB should be the same type as that for the isopropylamine graft (P3). Indeed, Table 2 shows that this combination produces a close match to the AAMD data, and is therefore the most rational and internally consistent choice.

Table 2.

Log POW values for the Octylamine grafted unit from CGMD simulations. Log POW value from AAMD is 4.12. For each of these calculations, the second side chain is type C1.

| Side chain1 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone | |||||

| NDA | 5.67 | ||||

| P1 | 3.68 | ||||

| P2 | 4.60 | 4.21 | |||

| P3 | 3.85 | 3.71 | 3.17 | ||

| P4 | 3.64 |

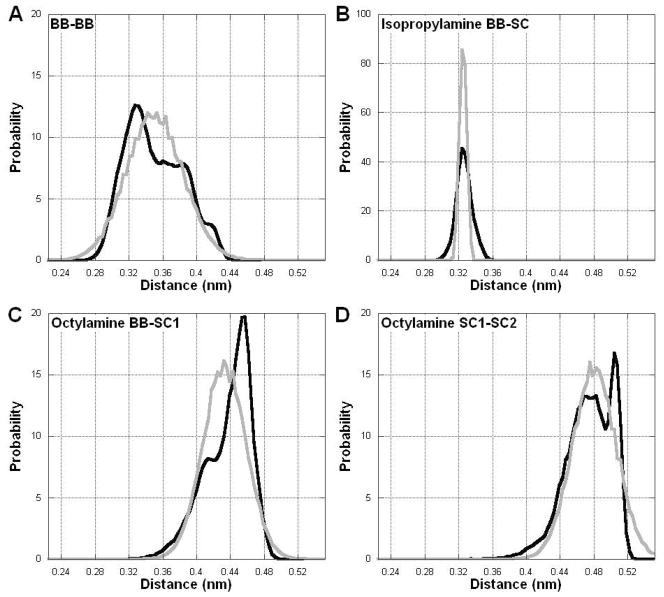

Bonded parameters are obtained through a similar strategy: the bond length, angle, and dihedral distributions are obtained from the AAMD simulations, and then the CGMD representation is altered until it matches the AAMD results. The bond length distributions for the AAMD representation and the simulations using the optimized CGMD parameter set are shown in Figure 3. We quantify the agreement between the two parameter sets by calculating the area overlap of the two curves, i.e. the fraction of the AAMD distribution which is matched by the CGMD distribution (Eq 7). For the bond lengths, the best agreement is obtained by the BB-BB bond (s=0.87). The worst agreement is from the isopropylamine BB-SC distribution, where the AAMD distribution is too narrow to be matched by a harmonic potential. Bonds of this nature, such as the similar Backbone – Side chain bond in the amino acid valine 39, are more stably modeled as distance constraints, though this leads to a relatively poor agreement (s=0.66). The need to balance stability and accuracy is a recurring issue in CGMD parametrizations. For the other two bonds, the AAMD distributions are matched relatively well by the CGMD model (octylamine BB-SC1 s=0.81 and octylamine SC1-SC2 s=0.86).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the bond distance distributions from the all-atom and coarse-grained models (AAMD = black, CGMD = gray).

Parametrizing the angles used in the CGMD representation presents similar challenges, as shown in Figure 4. Two of the CGMD angles match the AAMD data very well, BB-BB-SC s=0.93 and the octylamine BB-SC1-SC2 s=0.86. Note that the same BB-BB-SC potential is applied to both possible side chain graftings, as was the case for the protein parametrization 39. In the case of the BB-BB-BB angle, increased stability was found using a harmonic potential, rather than a cosine-harmonic, and using a narrower distribution, as in a recent parametrization study 34. Although this increases the stability, the agreement between the CGMD and AAMD models becomes relatively weak (s=0.69). Finally, the proper dihedral connecting four backbone beads matches the AAMD data very well (s=0.94). The bonded parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the angle and dihedral angle distributions from all-atom and coarse-grained models (AAMD = black, CGMD = gray).

Table 3.

Bonded Parameters for CGMD model.

| Molecule | Bonds | RBond (nm) | KBond (kJ mol−1 nm−2) | Angles | θ0 (deg) | KAngle (kJ mol−1) | Dihedrals | Φ0 (deg) | KDihedral (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backbones | BB-BB | 0.350 | 2000 | BB-BB-BB | 80 | 20* | BB-BB-BB-BB | 0 | 3 |

|

| |||||||||

| Isopropylamine | BB-SC | 0.325 | ‡ | BB-BB-SC | 120 | 5 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Octylamine | BB-SC1 | 0.435 | 4000 | BB-BB-SC1 | 120 | 5 | |||

| SC1-SC2 | 0.485 | 4000 | BB-SC1-SC2 | 180 | 30 | ||||

Harmonic potential is employed for angle term, rather than cosine-harmonic potential.

Bond is parametrized with a constraint, rather than a distance harmonic potential.

CGMD parametrization is complicated by the goal of creating a single set of parameters that are applicable in a variety of thermodynamic conditions 65. However, it is not certain whether the same set of bonded and non-bonded parameters should be used for polymers with different grafting sequences, length, association number, or bound to a membrane or MP. We have investigated this question, and found only a weak dependence in the cases available to us. For example, the three AAMD simulations using different sequences have a very large degree of similarity, with each bond, angle, and dihedral having an overlap value s>0.83 (Figure S2). We present additional information interrogating this issue as supplemental, though in general it remains a valid concern for all CGMD simulations (Figures S3–S5).

A8-35 Characterization

In this section we characterize the particle structures formed in the three separate sets of simulations (schematically depicted in Figure 2). The first set is the original AAMD simulations, which were obtained starting from an arbitrary initial configuration; however their limited duration prevents large scale reorganization. This motivated the parametrization of the CGMD model, as described above.

The second set of simulations uses the CGMD model to simulate de novo particle assembly. In Figure 5 we present snapshots from a CGMD simulation illustrating the assembly of four polymer chains into a single particle. The starting configuration is composed of four linear, extended chains, each separated by at least 3 nm. On a timescale of nanoseconds, the polymers collapse into individual bundles, partially shielding the hydrophobic octylamine chains from the solvent. This drive to shield the hydrophobic components leads to fusion of the separate chains into a single particle. While this fusion requires overcoming the repulsion due to the negatively charged, ungrafted carboxylates on the particle periphery, we have observed fusion to occur in every case, although the rate varies from ~100 ns (as in Figure 5) to ~1 μs. It is also important to note that the timescale of CGMD simulations is somewhat uncertain, and there is often a “speed-up” effect relative to AAMD simulations 37.

Figure 5.

Snapshots from CGMD simulation illustrating de novo particle assembly (blue = ungrafted, red = octylamine grafted, gray = isopropylamine grafted, water and ions removed for clarity).

The third set of simulations employs the final configuration of the CGMD trajectory as the starting point for a set of simulations at the all-atom resolution. These reverse coarse-grained (rCG) simulations allow us to investigate the structure of these particles using an organization derived from the CGMD model, rather than an arbitrary starting configuration, as in the original AAMD simulations. Over the course of the rCG simulations, the structure relaxes on the atomistic scale, as shown by the RMSD (presented as Figure S6), but the larger scale molecular organization does not change.

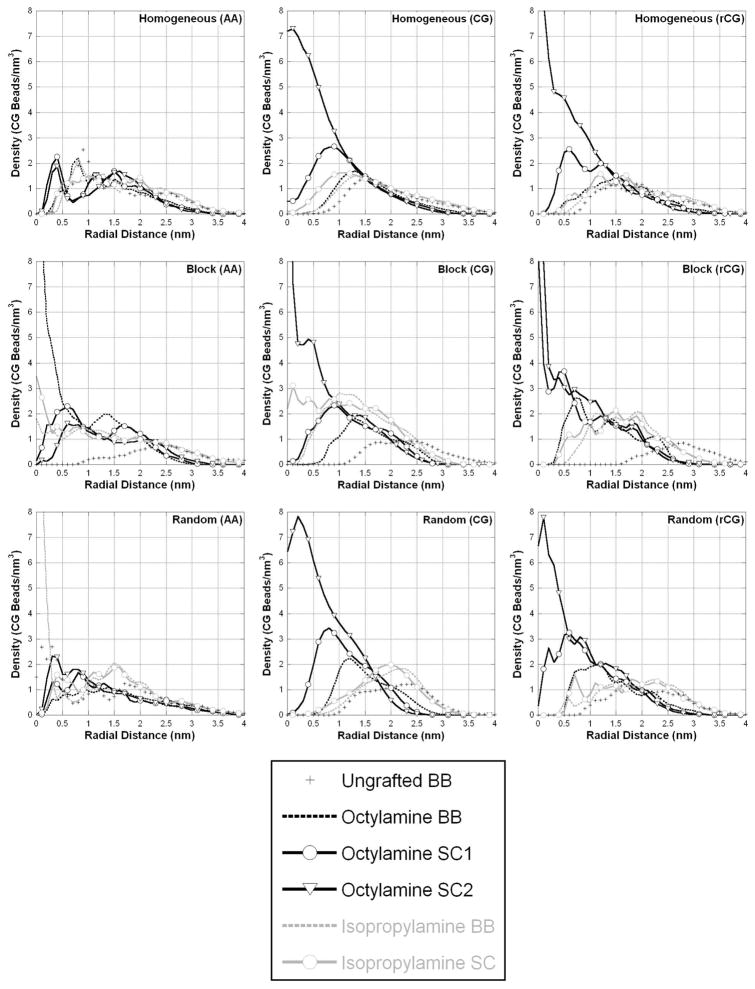

This molecular organization is described by the radial component density distribution, presented in Figure 6. This figure most clearly shows the differences between the different simulation strategies. In the AAMD simulations of the Homogeneous and Random sequences, the components appear to be almost randomly distributed throughout the particle, with a minimal degree of segregation of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic components. Only in the Block sequence can we observe a strong tendency for the hydrophobic contents to be enriched in the center of the particle and charged components to be on the outside of the particle. However, in the CGMD simulations there is in each case a very clear pattern of separation: the side chains of the octylamine form a hydrophobic core surrounded by the ungrafted, charged carboxylates. For the CGMD simulations, each sequence was simulated three times, and the results are entirely consistent. We present in Figure 6 the average of the three simulations. In the rCG simulations, the distributions of components taken from the CGMD coordinates are stable, and there is no change in the organization on the nanosecond time-scale, though there is a difference in sampling between the resolutions.

Figure 6.

Component radial density distributions describe the organization of the particle, contrasting the different simulation strategies.

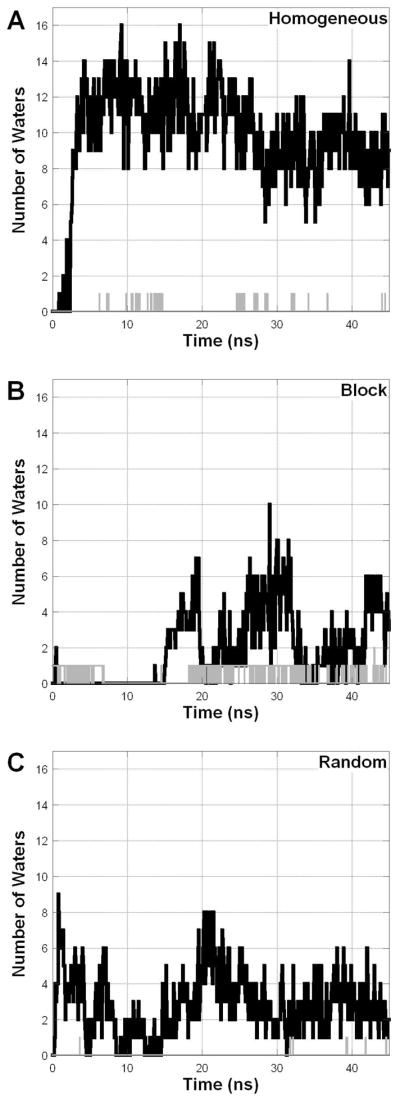

The character of the particle interior is of great interest due to its role in stabilizing MPs. The available experimental data are ambiguous: small angle neutron scattering (SANS) of A8-35 particles containing deuterated octyl- and isopropylamine side chains have suggested the existence of a hydrophobic core, but the data collected on unlabeled A8-35 were inconclusive, possibly because of insufficient contrast 9, 16. The particles we observe in the AAMD and rCG simulations have very different particle cores, as demonstrated in Figure 7, which shows the number of water molecules within 0.5 nm of the center of mass. The AAMD simulations have a core that is to a surprising degree, permeable to water. In particular, in the AAMD simulation of the Homogeneous sequence there is a near bulk density of water at the particle center. This feature appears to be reversible, with the Block and Random sequences showing a water permeated core in various periods of simulation time, whereas at other times, there is substantially less water penetration. These fluctuations occur on the timescale of nanoseconds to tens of nanoseconds, suggesting that the duration of our simulations is appropriate for studying this feature. In contrast to these AAMD simulations, in the rCG simulations there is practically no water in the particle center, as these particles form hydrophobic, water excluding domains. If the results of the rCG simulations are any guidance, it seems plausible that APols can effectively shield the transmembrane surface of MPs from contact with water.

Figure 7.

The number of water molecules found within 0.5 nm of the amphipol center of mass (AAMD = black, rCG = gray).

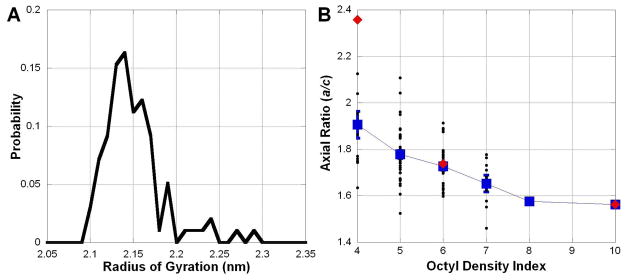

A common way of describing the structure of polymer particles is through their radius of gyration (Rg). Figure 8 presents the particle Rg over the simulation time for all three sets of simulations. SANS studies of experimental A8-35 samples, which are comprised of an ensemble of sequences, concluded that A8-35 particles have an average Rg of 2.4 ± 0.2 nm 16. The AAMD simulations are on the larger side of this range, with the Block (2.59 nm) and Random (2.60 nm) particles being slightly larger than the Homogeneous particle (2.44 nm). For the CGMD model, the three separate simulations for each sequence give very similar results and we chose to treat the separate simulations as independent samples, allowing us to include a standard error on our estimate of Rg. Compared to the AAMD simulations, in the CGMD simulations the particles in general are smaller, with, in this case, the Homogeneous particles (2.44 ± 0.04 nm) being larger than the Block (2.15 ± 0.04 nm) or Random (2.16 ± 0.01 nm) particles. This pattern is consistent for the rCG simulations, which relax over the course of the trajectory to slightly larger values than the CGMD simulations, with the Homogeneous particles (2.49 nm) being larger than the Block (2.34 nm) or Random (2.32 nm) particles. The Rg obtained from the AAMD and rCG Random particles, which we hypothesize best represent the actual sequence distribution in A8-35 samples, is within experimental error from that determined by SANS 16.

Figure 8.

Radii of gyration over time, describing structural relaxation and contrasting the different simulation strategies.

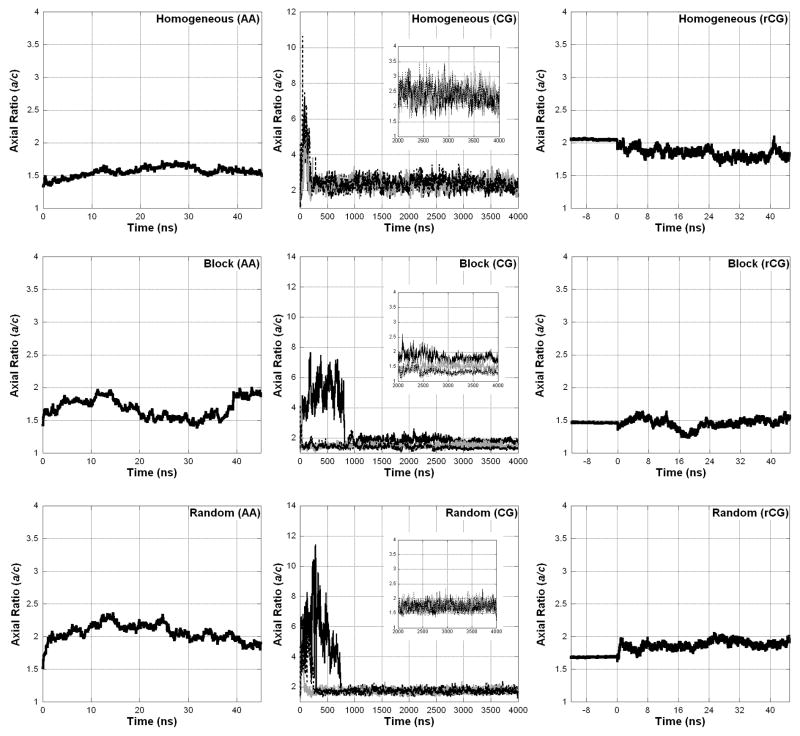

To describe the shape of A8-35 particles, we present the axial ratios of semi-ellipses calculated from the particle moments of inertia in Figure 9 (see Eq 9). For this parameter, a value of 1 would indicate a sphere, while larger values indicate a more elongated structure. SANS data suggest that the average A8-35 particle is nearly spherical, with axial ratios expected to be <2 (ref 16). This is in agreement with all of the simulations, except the CGMD simulation of the Homogeneous sequence. Note that the shape of the particle is related to the Rg, a more extended particle having a larger Rg than a spherical particle. Indeed, the CGMD simulation of the Homogeneous sequence yields the most extended particles, whose Rg is significantly larger than the other CGMD simulations.

Figure 9.

Particle shape is described by fitting the structure to an ellipsoid and calculating the semiaxial ratio (a/c), with 1 indicating a spherical particle and larger values indicating elongation.

In Figure 10 we compare SANS profiles calculated from simulation with experimental data 16. Note that the experimental data are the same in each panel and come from scattering on an ensemble of polymer lengths and grafting sequences. The region of interest for particles of this size is 0.0015 < Q2 < 0.0055 Å−2, while the excess scattering at lower angle is due to a tiny fraction of larger aggregates 16, which are not present in the simulations. The relevant feature of these profiles is the slope, which according to the Guinier relation, is linear and related to the Rg of the particles (Eq 8). For each of the three sequences, the SANS calculated from the AAMD and rCG simulations matches the experimental data fairly well in this region, with the slopes having a percent error of <15% in all cases.

Figure 10.

SANS from experimental ensemble (gray triangles) [Gohon et al. 2006], AAMD simulations (solid), and rCG simulation (dotted). The vertical dotted lines indicate the Guinier region, in which the linear slope of these profiles can be related to the radius of gyration.

While comparison with the SANS data shows that MD models are compatible with existing experimental evidence, it does not allow us to differentiate between the different simulation strategies. The three sequences and two methods provide us with particles featuring a range of component segregation, water content, Rg, and shape (or a/c axial ratio), as characterized in Figures 6–9. For example, the AAMD Homogeneous particle has minimal component segregation and a high internal water content, while the rCG Homogenous particle has a larger degree of segregation and almost no internal water content. However, as shown in Figure 10, their calculated SANS profiles are indistinguishable, with the slopes differing by only ~3%. Indeed, the structural information obtained in this region of q-space is on the nanometer scale, and is thus sensitive to the overall particle size, but not to the higher resolution features MD simulations can access. Therefore, we use this experimental data to demonstrate that all of our particles are of the appropriate size, without suggesting differences in agreement due to other observed structural features.

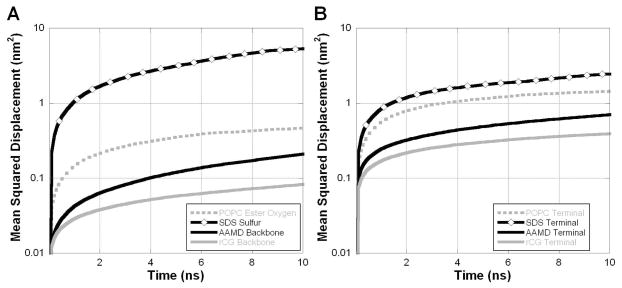

Previous work has led to the hypothesis that the dynamics of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1a) may be damped when the protein is trapped in APols, relative to lipid bilayers or detergent micelles, suggesting that protein experiences a more viscous environment 9, 11, 19, 66. Figure 11 presents the average mean squared displacement (MSD) for the AAMD and rCG A8-35 particles, as well as an all-atom POPC lipid bilayer and an all-atom SDS detergent micelle (with additional details regarding the latter simulations available elsewhere 29, 61). Figure 11A shows the MSD for peripheral atoms, specifically the APol backbone α-carbons, the POPC ester oxygens, and the SDS sulfurs. Figure 11B shows the MSD for the terminal methyl carbons from the APol octylamine grafts, the POPC palmitoyl chains, and the SDS hydrocarbon chains. The central conclusion is that the MSDs are lower in APols as compared to the lipid bilayer and detergent micelle. In both the hydrophobic molecular core and molecular periphery, the SDS molecule is the most dynamic, the POPC is intermediate, and the amphipol is the most restrained. These results suggest that APols provide the transmembrane domain with an environment that is indeed more viscous than those of lipid bilayers or detergent micelles, a difference consistent with current hypotheses about their effect on MP dynamics 9, 11, 19, 66.

Figure 11.

Mean squared displacement from amphipol simulations (AAMD and rCG) compared with POPC lipid bilayer and SDS detergent micelle, for peripheral atoms (A) and hydrocarbon chain terminals (B).

Discussion

The existence of numerous potential applications of APols for the stabilization and study of solubilized MPs has prompted a series of structural investigations of both APol particles and MP/APol complexes, using such experimental approaches as radiation scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation, size exclusion chromatography, and NMR (reviewed in ref 11). While these experimental studies have been insightful, they provide no information about the organization and dynamics of MP/APols complexes at the atomistic resolution. Here, we have taken the first steps towards this goal, by developing parameters for AAMD and CGMD simulation of APol A8-35 and characterizing the structure and dynamics of the self-assembled A8-35 particles.

Simulations of polymers could be considered a more challenging task than simulations of other macromolecules. For proteins, oligonucleotides, and most small molecules, the structure can be experimentally ‘solved,’ providing a well-defined set of atomic coordinates as a representative, equilibrium structure. However, for polymers, there is only minimal evidence to inform a starting configuration that is representative of the ensemble average. Given the limitations in computational power, AAMD simulations are generally restricted to durations of a few tens of nanoseconds. It is therefore not possible to obtain an equilibrated oligomeric structure starting from an unbiased initial configuration consisting of isolated polymer chains. While our AAMD simulations have clearly relaxed to a structure that is stable on the nanosecond timescale, the limited sampling available to AAMD inspired our decision to use a lower-resolution technique, CGMD, in order to obtain structures unbiased by our design. These CGMD simulations showed a clearly different organization, which we characterized at the AAMD resolution using a set of rCG simulations. The differences in structure between the original AAMD simulations and the rCG simulations strongly suggest that the AAMD simulations had not reached equilibrium.

A particularly intriguing feature that we have characterized here is the degree of segregation of the various groups that comprise the polymer and the character of the particle core. Aggregation of A8-35 into well-defined particles is thought to result from the octylamine chains segregating from water to form a hydrophobic core – as in the formation of detergent micelles - which intuitively agrees with the efficiency of APols at stabilizing MPs in aqueous solution. However, experimental evidence in favor of the formation of such a core has remained limited 9, 16. In our initial AAMD simulations, we find that relatively brief simulations starting from an arbitrary configuration settle into a state which is stable on the nanosecond timescale, in which the various groups are only partially segregated and which contains a substantial amount of internal water. These observations suggested that sampling was insufficient. Indeed, our much longer CGMD simulations consistently converge to a state with a well-defined hydrophobic core, which, according to rCG simulations, entirely excludes water.

Experimental batches of A8-35 are comprised of a highly polydisperse mixture of chains of various lengths and random graft sequences 8. In these simulations we have considered the impact of grafting sequence on the structure of the particles. The Homogeneous and Block sequences were chosen to explore the ability of these polymers to form hydrophobic clusters. All sequences, including the Block sequence, consistently show some degree of hydrophobic – hydrophilic segregation, even in the initial, brief AAMD simulations. However, given the relatively low computational cost of running CGMD simulations, we can broaden our study of the relationship between sequence and structure. Figure 12 presents the results from a “high-throughput” set of simulations, where 97 randomly generated sequences were run. Using this larger number of randomly generated sequences, we attempted to establish a relationship between grafting sequence and particle structure. To quantify the distribution of octylamines within a sequence, we define an Octyl Density Index, which is the maximal number of octylamine grafted units within any 10 sequential positions (though the results are consistent for a range of lengths). Using this parameter, the Homogeneous sequence has a value of 4, the Block sequence a value of 10, and the original Random sequence a value of 6. In Figure 12B, the particle a/c axial ratio is plotted as a function of the Octyl Density Index. These new simulations, in combination with the sequences already characterized, suggest that polymers with a more even distribution of octylamines tend to form particles with a more extended shape. Given this effect, we cannot exclude the possibility that the structure and functionality of the MP/APol complexes depend on the polymer sequence. Indeed, recent light scattering and electron microscopy studies point to a difference in size between random and block particles for a polymer analogous to A8-3567.

Figure 12.

A) Histogram of radius of gyration from 97 CGMD simulations using randomly generated sequences. B) These simulations suggest a relationship between particle shape (quantified by the a/c semiaxial ratio) and sequence. Black = random sequences, Blue = averages, Red = well-characterized sequences (from left to right Homogeneous, Random, and Block).

Similarly, we have used a series of CGMD simulations to examine the effect of polymer chain length on particle structure. SANS and AUC data indicate that the average A8-35 particle has a mass of ~40 kDa (ref. 16). According to original standard-based estimates 8, 18 of the average mass of A8-35 molecules, namely 9–10 kDa, this would correspond to an average of ~4 molecules per particle. More recent, standard-independent mass determinations suggest however that the average mass of individual A8-35 molecules more likely lies in the 4–5 kDa range (F. Giusti & J. Rieger, unpublished observations), in which case the average particle would comprise 8–10 chains. It is therefore useful to note that particles composed of chains either twice as long or half as long as those used in the main analysis, as well as unimolecular particles, present similar Rg and a/c axial ratios (Figure S7). This is consistent with early experimental data indicating that chains that are, on average, either ~4× longer 8 or 2× shorter 68 than those of A8-35 appear as efficient as it is at keeping MPs water soluble. On the contrary, CGMD particles composed of many (16 or more) much shorter chains are considerably more ellipsoid (Figure S7), suggesting that large excursions from the average chain length of A8-35 may entail differences in the structure and function of MP/APol complexes. Looking ahead to future work, we consider CGMD to offer two complementary paths to understanding the structure of APol particles and MP/APol complexes: 1) CGMD can generate structures for AA-resolution rCG simulations and, 2) CGMD can explore a structural relationship using a large number of simulations at a lower resolution.

A particularly valuable property of APols is their mildness towards MPs, whose stability is, a rule, considerably improved over that in detergent (see e. g. 8, 11, 20, 66, 69). This property has been tentatively traced to three mechanisms (for a more extended discussion, see 11). First, the use of APols makes it possible to reduce the amount of free surfactant, which acts as a hydrophobic sink into which stabilizing lipids, cofactors and subunits can diffuse away. Second, APols are intrinsically less dissociating than detergents, because they compete less efficiently with the protein-protein and protein-lipid interactions that stabilize the 3D structure of MPs. The third, hypothetical effect has been dubbed the ‘Gulliver effect’. Based primarily on observations carried out on the sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase (SERCA1a), it postulates that APols do not interfere much with small-scale movements at the transmembrane surface of MPs 69, 70, but slow down larger-scale movements, such as those involved in the enzymatic cycle of SERCA1a 19, 66 or in MP denaturation 9, 11, 19. This hypothesis is supported by the present analysis of the dynamics of A8-35 particles, which shows that movements that cannot be accommodated by the rearrangement of octyl chains will be hampered by the much less dynamic APol backbone, whose viscosity is higher than that of the polar head region of a detergent micelle, or even a lipid bilayer.

It is interesting to speculate on how the organization of a MP-adsorbed APol layer may differ from that of the free APol particle. On the one hand, the hydrophobic transmembrane surface of the protein may drive the clustering of octylamine chains around it, creating a layer that could be even more hydrophobic than that of the core of free APol particles. On the other hand, it is possible that the layer immediately in contact with the protein transmembrane surface be not exclusively hydrophobic, as suggested by NMR data on the interaction between A8-35 and the transmembrane β-barrel of Escherichia coli’s OmpA: while it was found that one face of the barrel strongly interacts with the octylamine and/or isopropylamine grafts, the other face showed less dense interactions with the hydrophobic polymer side chains 13. The structure and function of OmpA in multiple environments has been well studied through MD simulation 71, suggesting that we can use MD to address the affect of the APol environment on MP behavior.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Computational resources were provided by the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute (MSI). We thank Christopher Valley for discussion and Christophe Tribet (Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris) for helpful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. GM46376) for partial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Supplemental figures are provided as Supporting Information. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.White SH. The progress of membrane protein structure determination. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1948–9. doi: 10.1110/ps.04712004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granseth E, Seppala S, Rapp M, Daley DO, Von Heijne G. Membrane protein structural biology--how far can the bugs take us? Mol Membr Biol. 2007;24:329–32. doi: 10.1080/09687680701413882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowie JU. Solving the membrane protein folding problem. Nature. 2005;438:581–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachs JN, Engelman DM. Introduction to the membrane protein reviews: the interplay of structure, dynamics, and environment in membrane protein function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:707–12. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.110105.142336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garavito RM, Ferguson-Miller S. Detergents as tools in membrane biochemistry. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32403–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gohon Y, Popot JL. Membrane protein-surfactant complexes. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;8:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popot JL. Amphipols, nanodiscs, and fluorinated surfactants: three nonconventional approaches to studying membrane proteins in aqueous solutions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:737–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052208.114057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot JL. Amphipols: polymers that keep membrane proteins soluble in aqueous solutions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15047–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popot JL, Berry EA, Charvolin D, Creuzenet C, Ebel C, Engelman DM, Flötenmeyer M, Giusti F, Gohon Y, Hervé P, Hong Q, Lakey JH, Leonard K, Shuman HA, Timmins P, Warschawski DE, Zito F, Zoonens M, Pucci B, Tribet C. Amphipols: polymeric surfactants for membrane biology research. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1559–74. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3169-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders CR, Kuhn Hoffmann A, Gray DN, Keyes MH, Ellis CD. French swimwear for membrane proteins. Chembiochem. 2004;5:423–6. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popot JL, Althoff T, Bagnard D, Banères JL, Bazzacco P, Billon-Denis E, Catoire LJ, Champeil P, Charvolin D, Cocco MJ, Crémel G, Dahmane T, de la Maza LM, Ebel C, Gabel F, Giusti F, Gohon Y, Goormaghtigh E, Guittet E, Kleinschmidt JH, Kühlbrandt W, Le Bon C, Martinez KL, Picard M, Pucci B, Sachs JN, Tribet C, van Heijenoort C, Wien F, Zito F, Zoonens M. Amphipols from a to z. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catoire LJ, Damian M, Giusti F, Martin A, van Heijenoort C, Popot JL, Guittet E, Banères JL. Structure of a GPCR ligand in its receptor-bound state: leukotriene B4 adopts a highly constrained conformation when associated to human BLT2. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9049–57. doi: 10.1021/ja101868c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoonens M, Catoire LJ, Giusti F, Popot JL. NMR study of a membrane protein in detergent-free aqueous solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8893–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503750102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catoire LJ, Zoonens M, van Heijenoort C, Giusti F, Guittet E, Popot J-L. Solution NMR mapping of water-accessible residues in the transmembrane beta-barrel of OmpX. Eur Biophys J. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tribet C, Audebert R, Popot JL. Stabilization of hydrophobic colloidal dispersions in water with amphiphilic polymers: application to integral membrane proteins. Langmuir. 1997;13:5570–5576. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gohon Y, Giusti F, Prata C, Charvolin D, Timmins P, Ebel C, Tribet C, Popot JL. Well-defined nanoparticles formed by hydrophobic assembly of a short and polydisperse random terpolymer, amphipol A8-35. Langmuir. 2006;22:1281–90. doi: 10.1021/la052243g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoonens M, Giusti F, Zito F, Popot JL. Dynamics of membrane protein/amphipol association studied by Forster resonance energy transfer: implications for in vitro studies of amphipol-stabilized membrane proteins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10392–404. doi: 10.1021/bi7007596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gohon Y, Pavlov G, Timmins P, Tribet C, Popot JL, Ebel C. Partial specific volume and solvent interactions of amphipol A8-35. Anal Biochem. 2004;334:318–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picard M, Dahmane T, Garrigos M, Gauron C, Giusti F, le Maire M, Popot JL, Champeil P. Protective and inhibitory effects of various types of amphipols on the Ca2+-ATPase from sarcoplasmic reticulum: a comparative study. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1861–9. doi: 10.1021/bi051954a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahmane T, Damian M, Mary S, Popot JL, Banères JL. Amphipol-assisted in vitro folding of G protein-coupled receptors. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6516–21. doi: 10.1021/bi801729z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pocanschi CL, Dahmane T, Gohon Y, Rappaport F, Apell HJ, Kleinschmidt JH, Popot JL. Amphipathic polymers: tools to fold integral membrane proteins to their active form. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13954–61. doi: 10.1021/bi0616706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karplus M, Kuriyan J. Molecular dynamics and protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6679–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408930102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karplus M, McCammon JA. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:646–52. doi: 10.1038/nsb0902-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klepeis JL, Lindorff-Larsen K, Dror RO, Shaw DE. Long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of protein structure and function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:120–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrink SJ, de Vries AH, Tieleman DP. Lipids on the move: simulations of membrane pores, domains, stalks and curves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:149–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucerka N, Perlmutter JD, Pan J, Tristram-Nagle S, Katsaras J, Sachs JN. The effect of cholesterol on short- and long-chain monounsaturated lipid bilayers as determined by molecular dynamics simulations and X-ray scattering. Biophys J. 2008;95:2792–805. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rog T, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Vattulainen I, Karttunen M. Ordering effects of cholesterol and its analogues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:97–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feller SE. Molecular dynamics simulations of lipid bilayers. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;5:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlmutter JD, Braun AR, Sachs JN. Curvature dynamics of alpha-synuclein familial Parkinson disease mutants: molecular simulations of the micelle- and bilayer-bound forms. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7177–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808895200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ash WL, Zlomislic MR, Oloo EO, Tieleman DP. Computer simulations of membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:158–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gumbart J, Wang Y, Aksimentiev A, Tajkhorshid E, Schulten K. Molecular dynamics simulations of proteins in lipid bilayers. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy G, Yethiraj A. Solvent effects in polyelectrolyte adsorption: computer simulations with explicit and implicit solvent. J Chem Phys. 2010;132:074903. doi: 10.1063/1.3319782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H, Venable RM, Mackerell AD, Jr, Pastor RW. Molecular dynamics studies of polyethylene oxide and polyethylene glycol: hydrodynamic radius and shape anisotropy. Biophys J. 2008;95:1590–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee H, de Vries AH, Marrink SJ, Pastor RW. A coarse-grained model for polyethylene oxide and polyethylene glycol: conformation and hydrodynamics. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:13186–94. doi: 10.1021/jp9058966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H, Larson RG. Molecular dynamics simulations of PAMAM dendrimer-induced pore formation in DPPC bilayers with a coarse-grained model. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:18204–11. doi: 10.1021/jp0630830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivas G, Discher DE, Klein ML. Self-assembly and properties of diblock copolymers by coarse-grain molecular dynamics. Nat Mater. 2004;3:638–44. doi: 10.1038/nmat1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7812–24. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perlmutter JD, Sachs JN. Inhibiting lateral domain formation in lipid bilayers: simulations of alternative steroid headgroup chemistries. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16362–3. doi: 10.1021/ja9079258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monticelli L, Kandasamy S, Periole X, Larson R, Tieleman D, Marrink S. The martini coarse-grained force field: extension to proteins. J Chem Theory and Comput. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ainalem ML, Campbell RA, Khalid S, Gillams RJ, Rennie AR, Nylander T. On the ability of PAMAM dendrimers and dendrimer/DNA aggregates to penetrate POPC model biomembranes. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:7229–44. doi: 10.1021/jp9119809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng LX, Ivetac A, Chaudhari AS, Van S, Zhao G, Yu L, Howell SB, McCammon JA, Gough DA. Characterization of a clinical polymer-drug conjugate using multiscale modeling. Biopolymers. 2010;93:936–51. doi: 10.1002/bip.21474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rossi G, Monticelli L, Puisto SR, Vattulainen I, Ala-Nissila T. Coarse-graining polymers with the MARTINI force-field: polystyrene as a benchmark case. Soft Matter. 2011;7:698–708. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catte A, Patterson JC, Bashtovyy D, Jones MK, Gu F, Li L, Rampioni A, Sengupta D, Vuorela T, Niemela P, Karttunen M, Marrink SJ, Vattulainen I, Segrest JP. Structure of spheroidal HDL particles revealed by combined atomistic and coarse-grained simulations. Biophys J. 2008;94:2306–19. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.115857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shih AY, Freddolino PL, Sligar SG, Schulten K. Disassembly of nanodiscs with cholate. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1692–6. doi: 10.1021/nl0706906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, III, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry III. The role of exact exchange. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:5648–5653. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating water. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the langevin piston method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Essman U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pederson LA. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen HC. Rattle: A “velocity” version of the shake algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. J Comp Phys. 1983;52:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez CA, Rzepiela AJ, De Vries AH, Dijkhuizen L, Hunenberger PH, Marrink SJ. Martini coarse-grained force field: extension to carbohydrates. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5:3195–2310. doi: 10.1021/ct900313w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khalid S, Bond PJ, Holyoake J, Hawtin RW, Sansom MS. DNA and lipid bilayers: self-assembly and insertion. J R Soc Interface. 2008;5(Suppl 3):S241–50. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0239.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hinner MJ, Marrink SJ, de Vries AH. Location, tilt, and binding: a molecular dynamics study of voltage-sensitive dyes in biomembranes. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:15807–19. doi: 10.1021/jp907981y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gautieri A, Russo A, Vesentini S, Redaelli A, Buehler MJ. Coarse-grained model of collagen molecules using an extended martini force field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2010;6:1210–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirkwood JG. Statistical Mechanics of Fluid Mixtures. J Chem Phys. 1935;3:300–313. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyubartsev AP, Jacobsson SP, Sundholm G, Laaksonen A. Solubility of Organic Compounds in Water/Octanol Systems. A Expanded Ensemble Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study of log P Parameters. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:7775–7782. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hess B, Kutzer C, Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E. Gromacs 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anezo C, De Vries AH, Holtje HD, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. Methodological Issues in Lipid Bilayer Simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:9424–9433. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perlmutter JD, Sachs JN. Experimental verification of lipid bilayer structure through multi-scale modeling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Svergun DI, Richard S, Koch MH, Sayers Z, Kuprin S, Zaccai G. Protein hydration in solution: experimental observation by x-ray and neutron scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2267–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guinier A, Fournet G. Small-angle scattering of X-rays. Wiley; New York: 1955. p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voth GA. Coarse Graining of Condensed Phase and Biomolecular Systems. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Champeil P, Menguy T, Tribet C, Popot JL, le Maire M. Interaction of amphipols with sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18623–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu RCW, Pallier A, Brestaz M, Pantoustier N, Tribet C. Impact of Polymer Microstructure on the Self-Assembly of Amphiphilic Polymers in Aqueous Solutions. Macromolecules. 2007;40:4276–4286. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gohon Y. Etude des interactions entre un analogue du fragment transmembranaire de la glycophorine et des polymeres amphiphiles: les amphipols. Univ. Paris VI; Paris: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gohon Y, Dahmane T, Ruigrok RW, Schuck P, Charvolin D, Rappaport F, Timmins P, Engelman DM, Tribet C, Popot JL, Ebel C. Bacteriorhodopsin/amphipol complexes: structural and functional properties. Biophys J. 2008;94:3523–37. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martinez KL, Gohon Y, Corringer PJ, Tribet C, Merola F, Changeux JP, Popot JL. Allosteric transitions of Torpedo acetylcholine receptor in lipids, detergent and amphipols: molecular interactions vs. physical constraints. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:251–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khalid S, Bond PJ, Carpenter T, Sansom MS. OmpA: gating and dynamics via molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1871–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.