Abstract

Nucleoside chemistry represents an important research area for drug discovery, as many nucleoside analogs are prominent drugs and have been widely applied for cancer and viral chemotherapy. However, the synthesis of modified nucleosides presents a major challenge, which is further aggravated by poor solubility of these compounds in common organic solvents. Most of the currently available methods for nucleoside modification employ toxic high boiling solvents; require long reaction time and tedious workup methods. As such, there is constant effort to develop process chemistry in alternative medium to limit the use of organic solvents that are hazardous to the environment and can be deleterious to human health. One such approach is to use ionic liquids, which are ‘designer materials’ with unique and tunable physico-chemical properties. Studies have shown that methodologies using ionic liquids are highly efficient and convenient for the synthesis of nucleoside analogs, as demonstrated by the preparation of pharmaceutically important anti-viral drugs. This article summarizes recent efforts on nucleoside modification using ionic liquids.

Keywords: Nucleosides, Ionic Liquids, Solubility, Antiviral Drugs

1. Introduction

Nucleosides are fundamental building blocks of biological systems. The natural nucleosides and their analogues find numerous applications as fungicidal, anti-tumor and antiviral agents [1-3]. Therefore, the chemistry of these compounds has been studied extensively and today nucleoside chemistry represents an important area of research for modern drug discovery. Some of well-known examples of nucleoside-based antiviral drugs include AZT (Zidovudine), ddC (2′,3′-dideoxycytidine), d4T (Stavudine), BVDU (Brivudine), TFT (Trifluridine), IDU (Idoxuridine), etc [4-6]. Moreover, with the emergence of antisense oligonucleotides and siRNA as potential and selective inhibitors of gene expression, chemical synthesis of therapeutic oligonucleotides has undergone revitalization during the last decade [7,8]. The increased interest in the nucleoside chemistry has motivated organic chemists to develop efficient and practical synthetic methods, and number of strategies have been devised to design nucleoside analogues. Though, several structural modifications have been achieved on the heterocyclic bases and/or on the sugar moiety of natural nucleosides [9-12], synthesis of modified nucleosides remains a major challenge. One of the difficulties commonly encountered is in selective protection of highly polar hydroxyl and amine groups. This task is further complex due to limited solubility of nucleosides in most organic solvents. Most commonly employed solvents for nucleoside reactions chemistry are highly polar e.g. pyridine, N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP). These solvents are also highly toxic and hazardous for environment and human health. Further more, these solvents are pose difficulty in recovery and reuse. This has inspired synthetic chemists to explore alternative approaches for synthesis of nucleoside-based compounds.

In the past decade, much attention has been devoted in search of new reaction media to avoid volatile organic solvents (VOS). In recent years, room-temperature ionic liquids (compounds that consist only of ions and are liquid at ambient temperature) (ILs) have emerged as high-tech reaction media of the future. This is because of their advantageous properties (viz., negligible vapor pressure, non-flammability, recyclability, high thermal stability) and their ability to dissolve a wide range of organic and inorganic compounds [13-16]. Most important, their properties of these ‘designer materials’ can be adjusted to the reaction needs by proper manipulation of cations and anions [17-19]. Apart from tunable physical and chemical properties of ionic liquids, their immiscibility with various organic solvents enables the biphasic separation of the desired products and recyclability of expensive catalysts [20-22]. Furthermore, their ability to dissolve complex molecules such as nucleosides and amino acids helps to perform efficient modification on these biologically active compounds under milder conditions [23-26]. Recently, ILs have attracted much attention as they have been used to enhance the selectivity and kinetics of various organic reactions and to dramatically influence the outcome to chemical reactions [27]. With these advantages the ILs have found an increased interest in synthetic chemistry in recent years. This article is focused on the recent developments made in nucleoside chemistry using ionic liquids as reaction medium. The stuctures of cationic and anionic components of ILs used in these studies are given in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of cationic and anionc components of ILs used in nucleoside chemistry.

2. Enhanced solubility of nucleosides in ionic liquids

Following the discovery of the first effective antiviral compd. (idoxuridine) in 1959, nucleoside analogs, esp. acyclovir (ACV) for the treatment of herpesvirus infections, have dominated antiviral therapy for several decades. However, ACV and similar acyclic nucleosides suffer from low solubility in aqueous and commonly used organic solvents. Considering their unique physiochemical properties, our first interest was to test their utility in dissolving nucleosides. As a test case we first studied the solubility of Thymidine in ionic liquids having 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate ([MOEMIM][BF4]), 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate ([MOEMIM][TFA]), 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([MOEMIM][PF6]), 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(triflic)imide ([MOEMIM][Tf2N]) and 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium nethanesulfonate [MOEMIM][OMs] [25]. Interestingly hydrophobic ionic liquids [MOEMIM] [PF6] and [MOEMIM] [Tf2N] and also hydrophilic ionic liquid [MOEMIM] [BF4] showed poor solubility for thymidine. On the other hand, the new ionic liquid [MOEMIM][TFA] showed good solubility for thymidine which is comparable with [MOEMIM][OMs]. This indicates that the cation of ionic liquid has little influence on much significant for solubility, while the solubility changes drastically by changing anion and keeping the cation same. Further, the solubility of thymidine was found to be good in ionic liquids 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate ([BMIM][TFA]) and ethylpyridinium trifluoroacetate ([EtPy][TFA]), both having trifluoroacetate as common anion (Figure 2). This observation again suggests that the anion has a major effect on the physical properties of ionic liquid including the solubility. Next, we studied the solubility of three ribonucleosides viz. adenosine (A), cytosine (C) and guanosine (G) in ionic liquids which were found to be best in case of T i.e. [MOEMIM][OMs], [MOEMIM][TFA], [BMIM][TFA] and [EtPy][TFA] and compared with the commonly used organic solvents for nucleosides i.e. DMF and pyridine. The ionic liquids [MOEMIM] [OMs] and [EtPy] [TFA] were found to be best solvents for ribonucleosides followed by [MOEMIM] [TFA] and [BMIM] [TFA] respectively. But all these ILs, in general, were found to be far better solvents as compared to pyridine and DMF. The solubility comparision of ribonucleosides in different ILs and organic solvents is described in Figure 3. The enhanced solubility of nucleosides in ILs wih methanesulfonate and trifluoroacetate anions suggests that oxygenated anions may form hydrogen bonding with the nucleosides, thereby increasing their solubility [26].

Figure 2.

Solubility of Thymidine in different ILs.

Figure 3.

Solubility comparison of ribonucleosides in different ILs and organic solvents.

3. Hydroxyl group protection of nucleosides in ILs

Synthesis of modified nucleosides requires manipulation of hydroxyl- and amino-groups present in the molecule. One of the intrinsic problems in nucleoside chemistry is selective protection of these functionalities.

We reported benzoylation of both ribo- and 2′- using benzoyl cyanide as benzoylation agent and DMAP as catalyst deoxyribonucleosides in ionic liquid [MOEMIM] [OMs] [28]. Interestingly, in these reactions selective benzoylation of sugar hydroxyl groups over amine group of nucleobase was observed and corresponding O-benzoylated nucleoside derivatives were obtained in high yields (Scheme 1). It is important to mention here that when we carried out similar reactions using pyridine as solvent, the selectivity towards O-benzoylation was only observed in case of 2′-deoxyadenosine, 2′-deoxycytidine and adenosine, while perbenzoylated derivatives were obtained in case of rest of the nucleosides. Due to poor solubility (especially guanosine and 2′- deoxyguanosine) in pyridine, reactions were carried out in excess of solvent, at higher temperature and longer reaction time resulting in loss of overall selectivity. On the other hand due to the high solubility of nucleosides in ILs, the reactions could be carried out under mild conditions and better selectivity. Also, the ILs were recovered from the reaction mixture and reused without any loss in product yield. This protocol for selective O-benzoylation of nucleosides proved to be much superior as compared to those reported in literature. However, this method suffers from the limitation that a highly toxic compound i.e. HCN is obtained as byproduct [28]. This problem was overcome by our subsequent studies which lead to modified method where [MOEMIM] [TFA] is the reaction medium, DMAP used as catalyst and benzoic anhydride as benzoylating agent (Scheme 2) [25]. The byproduct obtained is benzoic acid, which makes the workup process relatively safer. In all the reactions, selectivity was high and O-benzoylated derivatives were formed in good yields.

Scheme 1.

Selective O-benzoylation of ribo- and 2′-deoxyribonucleosides in IL [MOEMIM][OMs] using benzoyl cyanide as benzoylation agent.

Scheme 2.

Selective O-benzoylation of ribo- and 2′-deoxyribonucleosides in IL [MOEMIM][TFA] using benzoic anhydride as benzoylation agent.

Increased selectivity towards O-benzoylation in ILs could be due to high ionic character of the medium polarizing the −O-H bond, thereby, making hydroxyl moiety more nucleophilic then the −NH2 group of nucleosides. Here again, the IL could easily be recycled and reused [25].

4. Sugar modification of nucleoside in ILs: Synthesis of d4T

Stavudine, also known as 2′, 3′-didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine (d4T) is an anti-HIV drug which act as a reverse transcriptase inhibitor [29]. Several methods reported in literature for synthesis of this compound requires tedious reaction conditions, longer reaction time, use of expensive reagents, harmful solvents and often results in poor yields [30-34]. To overcome these challenges we studied the elimination reaction on 2′, 3′-anhydrothimidine in ILs with sodium hydride at 100 °C to give d4T in 5-10 minutes (Scheme 3) [35]. The literature method for same reaction using dimethyl acetate (DMA) required relatively more time for completion [31]. Same reaction under milder conditions i.e. using tBuOK in ILs at room temperature did not go to complete conversion and the desired product was obtained in 55-62% isolated yield in six hours (Scheme 3) [35].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of d4T in ILs.

5. Base modification of nucleosides in ILs

(E)-5-(2-bromovinyl)-2′-deoxyuridine (Brivudine or BVDU) is an anti-HSV drug which is highly specific inhibitor of herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) replication [36]. It is a modified form of 2′-deoxyuridine and has been synthesized from its carboxylic acid analogue E)-5-(2-carboxyvinyl)-2′-deoxyuridine by reaction with N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) using THF: H2O (3:2) [37] or DMF [38] as solvent. We investigated the utility of ionic liquids for this and found that even though the conversion was not 100%, the product was obtained in moderate to good yield (52-70%) (Scheme 4) [35].

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of BVDU in ILs.

5-Trifluoromethyl-2′-deoxyuridine (Trifluridine or TFT) is another anti-HSV antiviral drug, used primarily on the eye [39]. It can be synthesized from 2′-deoxyuridine (2′-dU) in three steps. First, the hydroxyl groups of 2′-dU is protected by acetylation to give 3′, 5′-diacetoxy-2-deoxyuridine. Generally, this reaction is carried out in Pyridine/DMAP [40] or acetonitrile/Et3N/DMAP [41] with excess of acetic anhydride, and the reaction time varies between 2 to 12 hr. When this reaction is carried out in ILs using DMAP as catalyst and acetic anhydride (2 eq.) as acylating agent the reactions were over in 20-25 minutes giving acetylated single product in 91% yield (Scheme 5) [35]. Moreover, no purification was required and the product was obtained by simple extraction. Three ILs used in this study could be reused up to four times with loss in yield. Further, the diacetyl derivative could be reacted with CF3COOH and XeF2 to obtain trifluoromethylation at C-5 position. Similar reaction has been reported earlier using excess of CF3COOH with 33% yield [42]. When this reaction was carried out in ILs, the yields were slightly higher and the product could be obtained up to 40% yield. Finally trifluridine can be obtained by de-protection of diacetyl derivative using NH3/MeOH (Scheme 5) [35].

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of TFT using ILs.

It is well known in the literature that rational variation at C-5 position of pyrimidine-based nucleosides can enhance their properties in terms of oral bioavailability; metabolic stability and pharmacokinetics etc. 5-Halopyrimidine nucleosides are of great pharmaceutical interest and have been extensively investigated due to their anti-neoplastic and anti-viral properties [43-46]. For example, Idoxuridine, also known as 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine marketed as Herples and Stoxil® is one of the drugs used for conjunctival and corneal disease associated with feline herpes virus. However, various methods reported for their synthesis have several limitations, such as use of strong oxidizing agents as catalysts (e.g. HIO3, HNO3, etc), toxic and difficult to use halogenating agents (e.g. ICl, I2, Br2, etc.), hazardous solvents (e.g. acetic acid, pyridine, CCl4 etc.), harsh reaction conditions, longer reaction time and multiple workup steps [47, 48]. These difficulties were removed when C-5 halogenation of uracil-based nucleosides and their O-acetylated derivatives was carried out using lithium halides as halogenating agents, cerric ammonium nitrate (CAN) as oxidizing agent and acetic acid or acetonitrile as solvents. We performed these reactions in ILs [MOEMIM] [OMs], [MOEMIM] [TFA], [BMIM] [Ms] and [BMIM] [TFA] [47]. Initial screening for optimum reaction conditions showed that the best results were obtained with 1.2 mol equivalent of lithium halides, 2.0 mol equivalent of CAN at 80 °C. The halogenation of acetylated and unacetylated 2′-dU and U were then carried out under these conditions and the yields were found to be comparable with those obtained with organic solvents. It is worth mentioning here that the acetylation of 2′-dU and U required for these reactions was also carried out in ILs at room temperature using DMAP as catalyst and acetic anhydride as acetylating agent and the yields of the desired acetylated derivatives was 89-93% (Scheme 6) [47].

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 5-halouridines and 5-halo-2′-deoxyuridines in ILs.

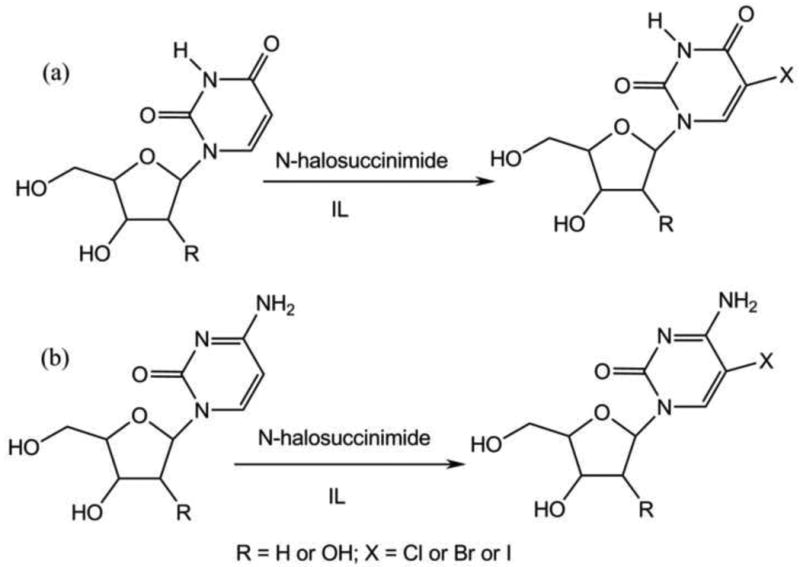

Motivated from these studies, we have recently developed a novel and highly efficient benign methodology for C-5 halogenations of pyrimidine-based nucleosides. Here N-halosuccinimides is employed as halogenating agents in ionic liquid medium and in absence of any catalyst [48]. The ionic liquids used for these studies were [MOEMIM] [OMs], [MOEMIM] [TFA], [BMIM] [Ms] and [BMIM] [TFA]. The reactions were simply carried out by dissolving the pyrimidine nucleosides i.e. 2′-deoxyuridine(2′-dU), uridine (U), 2′-deoxycytidine (2′-dC) or cytidine (C) in ILs, followed by addition of corresponding N-halosuccunimides (N-chlorosuccinimide for chlorination, N-bromosuccinimide for bromination and N-iodosuccinimide for iodination) and the reaction mixture were stirred at appropriate temperature (Scheme 7). On completion of reaction, the mixture was diluted with dichloromethane and purified directly with flash chromatography using dichlromomethane/methonol solvent system. Once the fractions containing pure Halogenated nucleosides were collected; the columns were eluted by methanol to recover the ILs which were reused after drying under vacuum oven. The C-5 chlorination when carried out in different ionic liquids at 50-60 °C it required 10-60 minutes (for different ILs and substrates) and gave the product in 82-92% yields. The bromination reaction was carried out at room temperature except for IL [BMIm][Ms] (which was solid at room temperature, m.p. 60 °C) to get the corresponding bromo- derivatives in 80-90% yields in just 5-30 minutes. Surprisingly, no iodination reactions was seen in ILs namely [BMIM] [OMs] and [MOEMIM] [OMs] even at elevated temperatures. Where as using ILs [MOEMIM] [TFA] and [BMIM] [TFA] the reactions were complete in 4 hours at 60 °C giving the corresponding iodo- derivatives in 60-89 % yields (Scheme 11) [48]. It is important to note that it requires 10-15ml of highly polar organic solvents (e.g. pyridine, DMF, etc.) to dissolve 1 mmol of nucleosides. On the other hand due to high solubility in appropriate ILs, only 1-1.5 ml of IL is required to dissolve these nucleosides. Therefore, the solvent consumption is decreased by nearly 10 folds makes the reaction easy to handle and workup.

Scheme 7.

IL mediated C-5 halogenation of: (a) uridines and (b) cytidines

6. Conclusion

In summary, ionic liquids have proven to be very effective solvents for nucleoside chemistry. They provide high solubility for nucleosides, allowing the reactions to be carried out under milder conditions with lower solvent consumption and easy workup. Our studies have shown that utility of ionic liquids in synthetic modifications of nucleoside e.g. selective O-protection and nucleobase modifications. This has been established through synthesis of representative commercial drugs. Ionic liquids can affect reaction kinetics resulting in lower reaction time. They can easily be recycled multiple times generating minimal waste. We believe that there is lot more scope for designing new ionic liquids with improved properties which can make them ideal solvents for every possible nucleoside reaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nasr M, Litterst C, McGowan J. Computer-Assisted Structure-Activity Correlations of Dideoxynucleoside Analogs as Potential Anti-HIV drugs. Antiviral Res. 1990;14:125–148. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(90)90030-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeClercq E. HIV Inhibitors Targeted at the Reverse Transcriptase. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 1992;8:119–134. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schinazi RF, Mead JR, Feorino PM. Insights into HIV Chemotherapy. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 1992;8:963–990. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeClercq E. Anitviral Drug Discovery and Development: Where Chemistry Meets with Biomedicine. Antiviral res. 2005;67:56–75. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeClercq E. Recent Highlights in the Development of new Antiviral Drugs. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathe C, Gosselin G. L-Nucleoside Enantiomers as Antivirals Drugs: A Mini-review. Antiviral Res. 2006;71:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhlmann A, Pyeman A. Antisense oligonucleotides: a new therapeutic principle. Chem Rev. 1990;90:543–584. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner RW. Gene Inhibition Using Antisense Oligodeoxynucleotides. Nature. 1994;372:333–335. doi: 10.1038/372333a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrero M, Gotor V. Biocatalytic Selective Modifications of Conventional Nucleosides, Carbocyclic Nucleosides, and C-Nucleosides. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4319–4348. doi: 10.1021/cr000446y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kool ET. Preorganization of DNA: Design Principles for Improving Nucleic Acid Recognition by Synthetic Oligonucleotides. Chem Rev. 1997;97:1473–1488. doi: 10.1021/cr9603791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi Y, Kumadaki I, Yamamoto K. Simple Synthesis of Trifluoromethylated Pyrimidine Nucleosides. J Chem Soc: Chem Commun. 1977:536–537. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cristofoli WA, Wiebe LI, De Clercq E, Andrei G, Snoeck R, Balzarini J, Knaus EE. 5-Alkynyl Analogs of Arabinouridine and 2′-Deoxyuridine: Cytostatic Activity against Herpes Simplex Virus and Varicella-Zoster Thymidine Kinase Gene-Transfected Cells. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2851–2857. doi: 10.1021/jm0701472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welton T. Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids: Solvents for Synthesis and Catalysis. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2071–2083. doi: 10.1021/cr980032t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wassercheid W, Keim W. Ionic Liquids-New “Solutions” for Transition Metal Catalysis. Angew Chem. 2000;39:3772–3789. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3772::aid-anie3772>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao H, Malhotra SV. Applications of Ionic Liquids in Organic Synthesis. Aldrichimica Acta. 2002;35:75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain N, Kumar A, Chauhan S, Chauhan SMS. Chemical and Biochemical Transformations in Ionic Liquids. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:1015–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranu BC, Banerjee S. Ionic Liquids as Catalyst and Reaction Medium. The Dramatic Influence of a Task-Specific Ionic Liquid, [bmIm]OH, in Michael Addition of Active Methylene Compounds to Conjugated Ketones, Carboxylic Esters, and Nitriles. Org Lett. 2005;7:3049–3052. doi: 10.1021/ol051004h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bates ED, Mayton RD, Ntai I, Davis JH., Jr CO2 Capture by a Task-Specific Ionic Liquid. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:926–927. doi: 10.1021/ja017593d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SG. Functionalized Imidazolium Salts for Task-Specific Ionic Liquids and their applications. Chem Commun. 2006:1049–1063. doi: 10.1039/b514140k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupont J, de Souza RF, Suarez PAZ. Ionic Liquid (Molten Salt) Phase Organometallic Catalysis. Chem Rev. 2000;102:3667–3691. doi: 10.1021/cr010338r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song CE. Enantioselective Chemo- and Bio-Catalysis in Ionic Liquids. Chem Commun. 2001:1033–1043. doi: 10.1039/b309027b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra SV, Kumar V, Parmar VS. Asymmetric Catalysis in Ionic Liquids. Curr Org Synth. 2007;4:370–380. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Malhotra SV. Enzymatic Resolution of Amino Acid Esters using Ionic Liquid N-ethylpyridinium Trifluoroacetate. Biotechnol Lett. 2002;24:1257–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao H, Luo RG, Wei D, Malhotra SV. Concise Synthesis and Enzymatic Resolution of L-(+)-homophenylalanine Hydrochloride. Enantiomer. 2002;7:1–3. doi: 10.1080/10242430210706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar V, Parmar VS, Malhotra SV. Enhanced Solubility and Selective Benzoylation of Nucleosides in Novel Ionic Liquid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:809–812. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uzagare MC, Sanghvi YS, Salunkhe MM. Application of Ionic Liquid 1-Methoxymethyl-3-methyl Imidazolium Methanesulfonate in Nucleoside Chemistry. Green Chem. 2003;5:370–372. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Earle MJ, Katdare SP, Seddon KR. Paradigm Confirmed: The First Use of Ionic Liquids to Dramatically Influence the Outcome of Chemical Reactions. Org Lett. 2004;6:707–710. doi: 10.1021/ol036310e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad AK, Kumar V, Malhotra S, Ravikumar VT, Sanghvi YS, Parmar VS. ‘Green’ Methodology for Efficient and Selective Benzoylation of Nucleosides using Benzoyl Cyanide in an Ionic Liquid. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:4467–4472. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansuri MM, Starrett JE, Jr, Ghazzouli I, et al. 1-(2,3-Dideoxy-β-D-glycero-pent-2-enofuranosyl)thymine. A highly Potent and Selective Anti-HIV agent. J Med Chem. 1989;32:461. doi: 10.1021/jm00122a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horwitz J, Chua J, Da Rooge MA, Noel M, Klundt IL. Nucleosides. IX. The Formation of 2′,3′-Unsaturated Pyrimidine Nucleosides via a Novel β-Elimination Reactions. J Org Chem. 1966;31:205–211. doi: 10.1021/jo01339a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi BV, Rao TS, Reese CB. Conversion of Some Pyrimidine 2′-Deoxyribonucleosides into the Corresponding 2′,3′-Didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxynucleosides. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1992:2537–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lipahutz BH, Stevens KL, Lowe RF. A Novel Route to the Anti-HIV Nucleoside d4T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:2711–2712. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen BC, Quinlan SL, Reid JG, Spector RH. A New Thymine Free Synthesis of the Anti-AIDS Drug d4T via Regio/Stereo Controlled β-Elimination of Bromoacetates. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:729–732. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paramashivappa R, Kumar PP, Rao PVS, Rao AS. Simple and Efficient Method for the Synthesis of 2′,3′-Didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine (d4T) Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:1003–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar V, Malhotra SV. Synthesis of Nucleoside-Based Antiviral Drugs in Ionic Liquids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5640–5642. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Clercq E. (E)-5-(2-Bromovinyl)-2′-deoxyuridine (BVDU) Med Res Rev. 2005;25:1–20. doi: 10.1002/med.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johar M, Manning T, Kunimoto DY, Kumar R. Synthesis and In-Vitro Anti-mycobacterial Activity of 5-substituted Pyrimidine Nucleosides. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:6663–6671. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashwell M, Jones AS, Kumar A, Jon R, Walker RT, Sakuma T, DeClercq E. Synthesis and Antiviral Properties of (E)-5-(2-Bromovinyl)2′-deoxyuridine-Related Compounds. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:4601–4608. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carmine AA, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Trifluridine: A Review of its Antiviral Activity and Therapeutic Use in the Topical Treatment of Viral Eye Infections. Drugs. 1982;23:329–353. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198223050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamaike K, Takahashi M, Utsugi K, Tomizuka K, Okazaki Y, Tamada Y, Kinoshita K, Masuda H, Yoshiharu I. Partial Protection of Carbohydrate Derivatives. Part 31. An Efficient Method for the Synthesis of [4-15N]Cytidine, 2′-deoxy[4-15]Cytidine, [6-15]Adenosine, and 2′-deoxy-[6-15]Adenosine Derivatives. Nucleosides & Nucleotides. 1996;15:749. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuda A, Itoh H, Takenuki K, Sasaki T, Ueda T. Nucleosides and Nucleotides. LXXXI. Alkyl Addition of Pyrimide 2′-Ketonucleosides: Synthesis of 2′-Branched-Chain Sugar Pyrimidine Nucleosides. Chem Pharm Bull. 1988;36:945–953. doi: 10.1248/cpb.36.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanabe Y, Matsuo N, Ohno N. Direct Perfluoroalkylation Including Trifluoromethylation of Aromatics with Perfluorocarboxylic Acids Mediated by Xenon Difluoride. J Org Chem. 1988;53:4582–4585. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang X, Li X, Fan X. Ionic Liquid Promoted Preparation of 4H-thiopyran and Pyrimidine Nucleoside-Thiopyran Hybrids Through One-Pot Multi-Component Reaction of Thioamide. Mol Diversity. 2009;13:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s11030-008-9098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perigaud C, Gosselin G, Imbach JL. Nucleoside Analogues as Chemotherapeutic Agents: A Review. Nucleosides & Nucleotides. 1992;11:903–945. [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Clercq E. Antiviral Activity of 5-Substituted Pyrimidine Nucleoside Analogs. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 1983;55:623–636. [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Clercq E, Balzarini J, Torrence PF, Metres MP, Schmidt CL, Shugar D, Barr PJ, Jones AS, Verhelst G, Walker RT. Thymidylates Synthetase as Target Enzyme for the Inhibitory Activity of 5-Substitutes 2′-Deoxyuridines on Mouse Leukemia L1210 Cell Growth. Mol Pharmacol. 1981;19:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar V, Malhotra SV. Ionic Liquid Mediated Synthesis of 5-Halouracil Nucleosides: Key Precursors for Potential Antiviral Drugs. Nucleosides, Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids. 2009;28:821–834. doi: 10.1080/15257770903170252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar V, Yapp J, Muroyama A, Malhotra SV. Highly Efficient Method for C-5 Halogenation of Pyrimidine-Based Nucleosides in Ionic Liquids. Synthesis. 2009:3957–3962. [Google Scholar]