Abstract

Pollen grains play important roles in the reproductive processes of flowering plants. The roles of apoplastic proteins in pollen germination and in pollen tube growth are comparatively less well understood. To investigate the functions of apoplastic proteins in pollen germination, the global apoplastic proteins of mature and germinated Arabidopsis thaliana pollen grains were prepared for differential analyses by using 2-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE) saturation labeling techniques. One hundred and three proteins differentially expressed (p value ≤ 0.01) in pollen germinated for 6h compare with un-germination mature pollen, and 98 spots, which represented 71 proteins, were identified by LC-MS/MS. By bioinformatics analysis, 50 proteins were identified as secreted proteins. These proteins were mainly involved in cell wall modification and remodeling, protein metabolism and signal transduction. Three of the differentially expressed proteins were randomly selected to determine their subcellular localizations by transiently expressing YFP fusion proteins. The results of subcellular localization were identical with the bioinformatics prediction. Based on these data, we proposed a model for apoplastic proteins functioning in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. These results will lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms of pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, pollen germination, apoplast, 2-D DIGE, proteomic

1. Introduction

The apoplast is the region of a plant cell beside the cell membrane. It includes the cell wall matrix and the intercellular space [1]. At first, the apoplast was thought to be a ‘dead’ compartment that differed from the ‘living’ symplast. However, in the intervening years, a considerable amount of research has shown that the apoplast is not only a transporter of water and solutions but also an important functional component required by the plant [1–7]. Compared to the animal internal environmental functions, Naoki Sakurai summarized some distinct functions of the plant apoplast, such as growth regulation, sustaining skeleton/structure, homeostasis of the internal environment, transportation route, and cell-to-cell adhesion e [8]. Proteins and peptides are essential composition for the plant apoplast. They play important roles in plant physiological and developmental processes [9–11]. Using a bioinformatics approach, Lease et al. found 33,809 open reading frames (ORFs) that encoded putative secreted peptides from A. thaliana chromosome sequences [12]. However, only about 400 cell wall proteins have been reported from Arabidopsis according to cell wall proteomic analyses [13]. These results encourage further investigation of the plant apoplast.

Sexual reproduction is an essential biological process in flowering plants [14]. During this process, complex signaling occurs between the male and female gametophytes to ensure successful fertilization [15]. The male gametophyte (pollen) apoplast is the only way to receive signals from the female gametophyte. Compared to the female gametophyte (egg cell), which is embedded in several maternal diploid cell layers of the ovule, the highly specialized haploid pollen is more easily isolated and manipulated for apoplast study [15].

Most pollen and pollen tube apoplast knowledge comes from screening mutants. Lots of identified molecules in pollen apoplast play essential roles in adhesion, hydration and pollen tube growth [16–19]. There are many oleosin-like proteins in the pollen coat that have been implicated in pollen hydration through the analysis of the A. thaliana glycine-rich protein (grp) 17 mutant [17]. The grp17 mutant, which lacks the GRP17 oleosin domain, is significantly delayed in hydration initiation compared to the wild-type. A pollen coat enzyme, which is encoded by the A. thaliana extracellular lipase 4 (exl4) gene, has also been implicated in pollen hydration [18]. The exl4 mutant pollen requires a significantly longer time for hydration. Significant amounts of pectin deposited at the surface of pollen and the pollen tube, which is also implicated in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. The A. thaliana VANGUARD1 (vgd1) gene is necessary for enhanced pollen-tube penetration into the style and for transmitting tract tissues [19], vgd1 encodes a pectin methylesterase, and the T-DNA insertion mutant of vgd1 results in a significant reduction of male fertility. Pollen coat proteins are also implicated in self-incompatible pollination. The S-locus cysteine-rich/S-locus protein 11 (SCR/SP11), which is a small pollen coat protein, can interact with the stigma-specific S-receptor kinase (SRK). This interaction activates the SRK signaling pathway and leads to the rejection of ‘self’ pollen [20]. The apoplast of the pollen tube is predicted to regulate the cessation of pollen tube growth. Escobar-Restrepo et al. found an A. thaliana protein FERONIA (FER), which is a receptor-like kinase localized to the cell membrane. The fer mutant pollen tubes grew continuously and did not discharge sperm into the embryo sac [21]. Although the ligand of FERONIA had not been identified, it was suggested to localize to the apoplast of the pollen tube [22].

The proteomes of A. thaliana mature pollen have been described in many previous work [23–26], and differentially expressed proteins during pollen germination have been previously analyzed in a few plant species including Pinus strobus[27], A.thaliana[28], canola[29], lily[30] and rice[31]. However, the apoplast proteome of pollen and the pollen tube is relatively not well-studied. The Arabidopsis pollen coat proteome was analyzed using SDS-PAGE combined with MS identification. Ten proteins were identified that mainly belonged to two genomic clusters. One cluster was the lipases, and the other was the lipid-binding oleosin family [32]. The apoplastic proteins of mature and germinated maize pollen were also separated by SDS-PAGE, and 11 proteins were identified [33]. Recently, Dai et al. analyzed Oryza sativa mature pollen coat proteins using SDS-PAGE combined with nano LC-MS/MS. Thirty-seven pollen coat-associated proteins were identified, and most were implicated in wall remodeling and metabolism [34]. The pollen-released proteins were also separated from rice mature pollen by isotonic elution. After 2-DE analysis and MS identification, 158 unique proteins were identified. These proteins were mainly involved in signal transduction, cell wall remodeling and modification, carbohydrate and energy metabolism and stress response [34]. All of these data expand our knowledge of pollen coat- and wall-associated proteins.

However, SDS-PAGE or traditional 2-DE sensitivity is still low, especially for the analysis of apoplastic proteins, which are typically of a low abundance. In this study, we utilized 2-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE), which is more sensitive and more repeatable compared to the previously mentioned methods [29, 35], for comparative analyses of the global apoplast proteomes from germinating arabidopsis thaliana pollen. One hundred and three spots were significantly differentially expressed, and 98 spots, which represented 71 proteins, were successfully identified. By bioinformatics analysis, more than 70% were identified as secreted proteins. These proteins were mainly involved in cell wall modification and remodeling, protein metabolism and signal transduction. These results will enhance our understanding of apoplast function during pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Pollen collection and viability testing

Mature pollen grains were collected from fresh flowers using a modified vacuum cleaner as previously described [36]. Freshly collected pollen was used immediately or stored at −80°C. Pollen grain viability was assessed by fluorescein diacetate staining and pollen germination in vitro on solid medium. The components and protocols have been described [19, 37, 38].

2.2. Pollen germination in liquid medium

The medium used has been previously described [38]. Vacuum-collected pollen was mixed with liquid germination medium at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. The pollen mixture was spread in 6-well plates using 300 µl per well. The liquid layer was kept thin [39]. Plates were incubated in a 22°C culture chamber for 6 h.

2.3. Preparation of apoplastic proteins

For the apoplastic proteins of mature pollen, freshly vacuum-collected pollen was weighed and mixed with wash buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10% sucrose, 13 mM DTT and 2 mM PMSF) at a concentration of 4 mg/ml. The wash buffer was modified on the basis of Dai et al.[34]. The mixture was incubated on a vertical mixer for 0.5 h in a chromatography freezer (4°C). The mixture was then filtered with 6-micron mesh. The filtered fluid was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min (4°C). The supernatant was lyophilized and stored at −80°C.

For germinated pollen, 6-well plates were used after 6 h of germination. The liquid germination medium was gently removed by pipetting, and an equal volume of wash buffer was added to each well. Plates were incubated on an orbital shaker for 0.5 h. The wash solution was then removed by pipette and filtered by using 6-micron mesh. The filtered fluid was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min (4°C). The supernatant was lyophilized and stored at −80°C. The proteins were purified using a clean-up kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ), and protein concentrations were measured using a 2-D Quant Kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

For immunoblots against tubulin, apoplastic proteins and total soluble proteins were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE, and stained with coomassie brilliant blue R-250 or transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was probed with anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (sigma, 1:2000 dilution). Alkaline phosphatase conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma, 1:10000) was used to develop the blot.

2.4. 2-D DIGE

The CyDye DIGE Fluor saturation dye was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare). Three independent biological replicates were performed (Supplement table 1). For differential analyses, 5 µg of proteins was adjusted to 9 µl with lysis buffer (30 mM Tris, 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea and 4%(w/v) CHAPS pH 8) and reduced using 2 nmol of Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP; 2 nM solution) for 1 h at 37°C. Then, 4 nmol of CyDye DIGE saturation dye (2 nM solution) was then added, and the sample was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. An internal standard was prepared by pooling equal amounts of each biological sample and then labeling the standard as described. To stop the labeling reaction, 12 µl of 2× sample buffer containing 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 130 mM DTT and 2% Pharmalyte (GE Healthcare) was added. Labeled samples were used immediately or stored at −80°C for future use. All labeling operations were performed in the dark.

Cy3-labeled samples were mixed with Cy5-labeled samples. The mixture was then added onto an Immobiline DryStrip (18 cm, pI range 4–7 linear gradient, (GE Healthcare) that had been rehydrated with 350 µl of rehydration buffer (7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 13 mM DTT and 1% Pharmalyte) overnight by a cup-loading method. The gel was covered with PlusOne Immobiline DryStrip Cover Fluid. A clear plastic strip cover was placed over the strip holder, and the apparatus was covered to exclude light. Then IEF was then performed as follows: 1000 V for 3 h, 3000 V for 3 h, 8000 V for 4 h. The temperature was maintained at 20°C. IEF was performed for a total of 36 kVh. After IEF, IPG strips were removed and equilibrated with equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 0.1 M Tris-HCL (pH 8.0), 30% glycerol, 2% SDS and 0.5% DTT) for 10 min at room temperature. The equilibrated IPG strips were transferred to the top of a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel and sealed with 0.5% low melting agarose. SDS-PAGE was performed with the Ettan Dalt six system (GE Healthcare) at a constant 1 W per gel for 18 h. All electrophoresis procedures were performed in the dark.

For preparative gels, 180 µg of protein prepared by pooling equal amounts of samples was labeled with Cy3 by upscaling the protocols used for analytical purposes. An in-gel rehydration approach was used for preparative gels. Other steps were identical to those used for analytical gels.

2.5. Imaging and biological variation analysis

Analytical gels were scanned using a Typhoon 9410 fluorescence scanner device (GE Healthcare). The parameters were set according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The images were analyzed by using DeCyder Differential Analysis Software version 6.5 (GE Healthcare). The experimental design using the two dye approach is illustrated in Table S1. The spot detection parameter for the differential in-gel (DIA) analysis module was set to 2000. In the biological variation analysis module (BVA), the intergel variability was corrected by normalization of the internal standard present in each gel, and the normalized protein spots were matched among the different gels. All matching spots were checked manually. Only spots with significant statistical changes in abundance (p value ≤ 0.01) were considered differentially expressed proteins.

2.6. Excision of 2-D gel spots and protein identification by LC-MS/MS

All spots with p value ≤ 0.01 were robotically excised into 96-well plates using an Ettan Spot Picker (GE Healthcare). Parameters were set according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gel plugs were digested in-gel with trypsin as previously described [40]. The peptides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS analyses on LTQ-FT or LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific), equipped with a Waters NanoAcquity LC system (Milford, MA). Peptides were trapped on a C18 trap column before separation in a 100µm ID × 100 mm long C18 analytical column, with a linear gradient from 2% solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) to 35% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at 350 nl/min over 35 min. The MS method was a “top-6” data dependent sequence with one survey scan in FT mode having mass resolution of 30,000 followed by 6 CID scans in LTQ targeting the first six most intense peptide ions whose m/z values were not in the dynamically updated exclusion list. The MS/MS data were searched against the Arabidopsis thaliana subset of the UniProtKB database (2009.01.01) using the in-house Protein Prospector search engine [41, 42], with a concatenated database consisting of normal and randomized decoy databases [43]. False discovery rates (FDRs) for protein identification was estimated to be 5%, corresponding to the expectation values of 0.05. Peak lists were searched against the individual protein isoforms were reported according to the detection of unique peptides for their sequences. For identifications based on one or two peptide sequences with high scores, the MS/MS spectrum was interpreted manually by matching all the observed fragment ions to a theoretical fragmentation obtained using Protein Prospector.

2.7. Bioinformatic analyses of identified proteins

The subcellular localizations of the identified proteins were predicted by two databases, TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org/). If there was no localization information, we used Signal P (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) to estimate whether it had a signal peptide, TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) to analyze the transmembrane domain and Target P (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) to predict whether they had a chloroplastid or mitochondrial signal peptide. Only the ones that containing signal peptides, and lacking transmembrane domains and ER retention signals, was considered to be a classical secreted proteins. We also use Secretome P (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP/) to predict non-classical secreted proteins.

2.8. Transient expression of YFP fusion proteins

YFP fusion proteins were cloned using Gateway technology (Invitrogen, pENTR™/SD/D-TOPO®, Carlsbad, CA and Gateway® LR Clonase™ II Enzyme Mix) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. pEarleyGate 101 was used as the destination vector [44]. Expression constructs were transformed into onion (Allium cepa) epidermal cells by particle bombardment [2]. After culturing for 22 h, transformed epidermal cells were treated with 0.9 M mannitol for plasmolysis and were observed for fluorescence under a confocal microscope (Zeiss 510 Meta).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Evaluation of pollen viability and germination

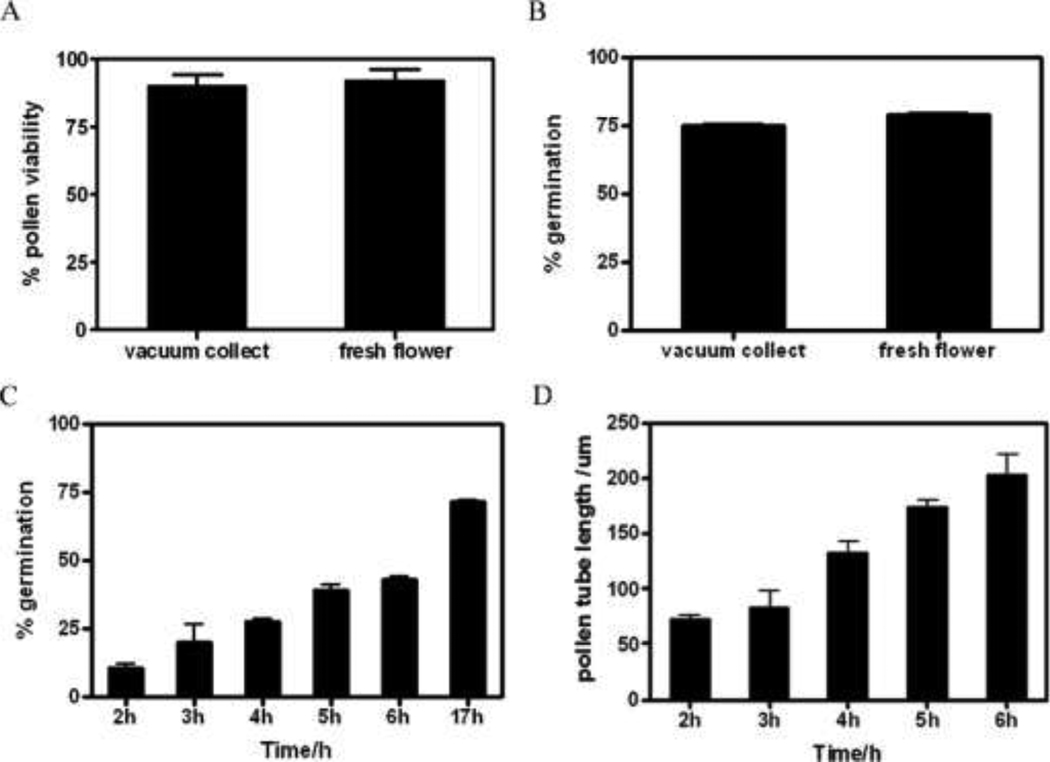

Desiccated mature pollen grains of A. thaliana were collected using a modified vacuum cleaner as previously described [36]. We compared the viability of bulk collected pollen with fresh flowers by fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining and pollen germination in vitro on solid medium (Fig. 1A), only the ones that the pollen tube length was more than the pollen ordinate diameter were regarded to germinated pollens. For fresh flowers, the pollen was 92% viable, and the germination rate was about 79% in vitro. For bulk collected pollen, the pollen was about 90% viable, and the germination rate was about 75%. There were no significant discrepancies between fresh pollen and bulk collected pollen (Fig. 1A–B).

Fig. 1. Detect the viability of bulk collected pollen and establish pollen germination system in vitro in liquid medium.

(A–B) Comparing the viability of bulk collected pollen with fresh flower pollen grains by FDA staining and pollen germination on solid medium. (A) Statistical results after FDA staining. (B) Statistical results of the pollen germination rate. (C–D) Pollen germinated in liquid medium. (C) Germination rates at different time (n=500). (E) Lengths of pollen tubes at different times (n=30). All experiments were repeated in triplicate, and each data point represents the mean ± SD.

For convenience, pollen was germinated in liquid medium for extracting apoplast proteins from germinated pollen. Apoplastic proteins were eluting after 6 h of germination. At this time, the germination rate was about 43%, and the average pollen tube length was 202 µm (Fig. 1C–D). Seventeen hours after pollen germination, the germination rate was about 74% (Fig. 1C). Therefore, about half viability pollen had been germinated at 6h. This stage could represent the initial phase of pollen germination, and the apoplastic proteins that involved in the initial stage could be represented.

3.2. Preparation of apoplastic proteins and 2-D DIGE

The apoplastic proteins were eluted from mature pollen and germinated pollen. Immunoblotting against tubulin was used to test the purity of pollen apoplastic fraction. As shown in Figure A. 2, tubulin was not detected in the apoplastic fractions but was clearly visible in cell total protein. This result indicated that there is no contamination of cytoplasmic proteins, or the contamination at a very low level.

The apoplastic proteins were analyzed by the 2-D DIGE saturation labeling method. Spot analysis using DeCyder software revealed more than 1000 spots were detected in this study, while only 480 spots were detected by colloidal Coomassie Blue (CCB) staining in an Oryza sativa study of pollen release proteins [34]. The greater number detected in this study could be due to the use of the DIGE technology, which is more sensitive than CCB staining. After biological variation analysis, 103 significantly differentially expressed spots (p value ≤ 0.01) were found. This is a relatively high number compared to the differential analysis of whole cell proteins from germinating rice and Pinus pollen. In rice, about 2300 protein spots (whole cell) were detected in germinated pollen, and 186 protein spots were differentially expressed [31]. In Pinus strobus, 650 protein spots (whole cell) were recognized in germinated pollen, and 57 were differentially expressed [27]. The relatively high number of differentially expressed spots in our results was not only due to the high sensitivity of the DIGE technology but also due to the separation of apoplastic proteins from intracellular proteins, which removed the abundant cytoplasmic proteins and then the low abundance apoplastic proteins could be detected. All differentially expressed proteins were excised, and 98, which actually represented 71 proteins, were successfully identified by LC-MS/MS.

3.3. Bioinformatic analyses of identified proteins

By using bioinformatic tools we analyzed the sublocalization of the identified proteins. Of the 71 identified proteins, 50 were cell wall or secreted proteins. Recently, proteins that did not contain signal peptides were found in the apoplast, and they were called non-classical secreted proteins [6]. For example, glutamine synthetase (GlnA) was the first reported protein with no signal peptide. However, it was a secreted protein. This suggested that there must be other ways for proteins to be transported to the apoplast. Bendtsen et al. developed Secretome-P (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP/) to predict non-classical secreted proteins in human and bacteria [45]. The mechanism of eukaryotes secretory evolved early and might to be common to animals and plants [13], so the Secretome-P was also used to identify the non-classical secreted proteins in plant [7, 13, 46–49]. In our study, there were 19 proteins belonged to non-classical secreted proteins. Intracellular contamination is a major problem for apoplast study. Until now, no extraction method for apoplastic proteins could totally prevent intracellular contamination. However, if more than 50% of identified proteins were apoplastic proteins, the extraction method was considered effective [50]. In our results, 70% of identified proteins were apoplastic proteins, which indicated the successful enrichment of pollen apoplastic proteins.

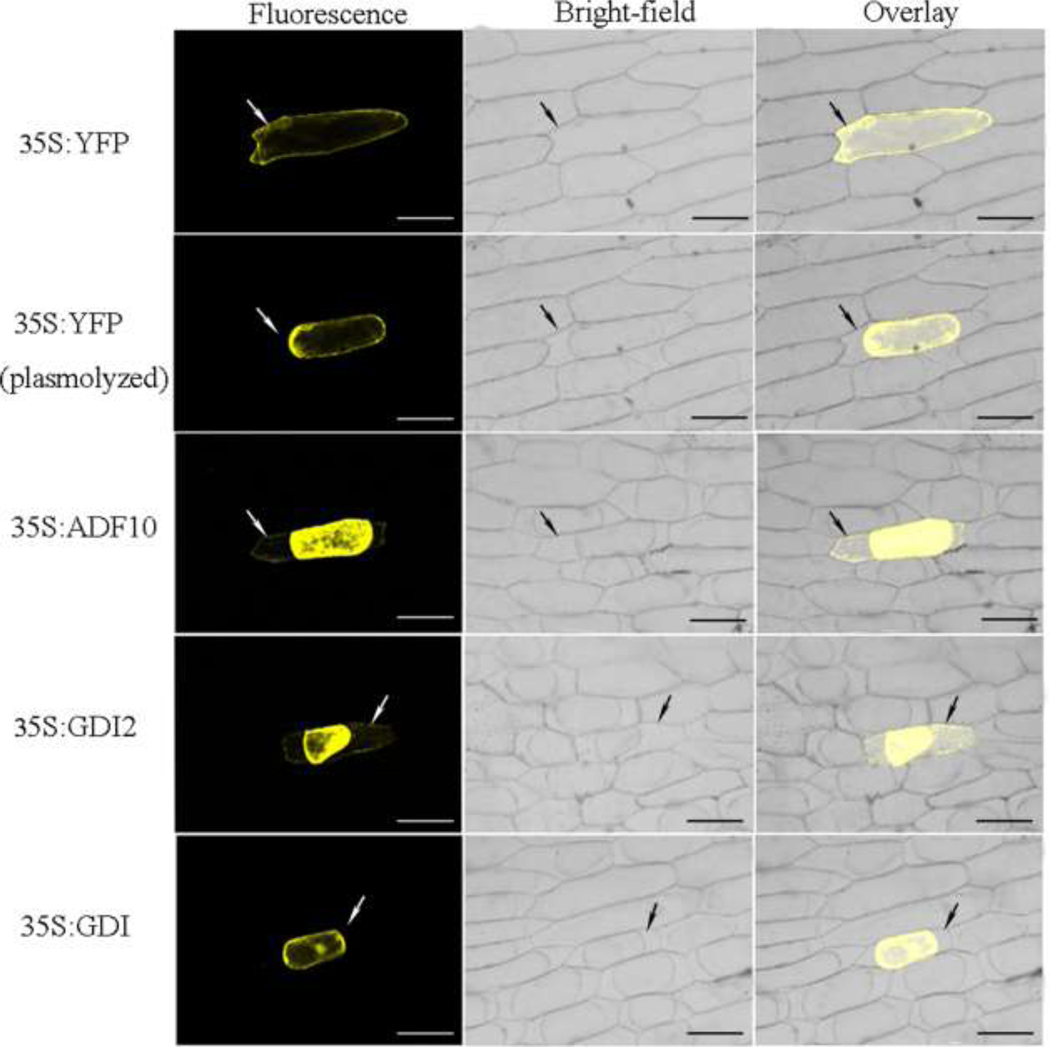

3.4. Subcellular localization of randomly selected proteins by transient expression of YFP fusion proteins

Except for some well-known apoplastic proteins, such as dienelactone hydrolase, esterase, pectinesterase, glycine-rich cell wall protein and extensin, there were many proteins with subcellular localizations predicted by bioinformatics tools. To test the veracity of these predictions, we randomly selected 3 proteins for further in vivo subcellular localization characterizations by the transient expression of YFP fusion proteins in onion epidermal cells. These proteins include an actin-depolymerizing factor putative ADF10 (spots 76, 78, 85, 82), a RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor GDI2 (spot 21) and a second RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor GDI (spots 23, 24, 29) (Table 1). The actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) family is thought to control the dynamic actin cytoskeleton, which is known to play a key role in pollen germination and pollen tube growth [51]. ADF10 was predicted to be secreted (http://suba.plantenergy.uwa.edu.au/flatfile.php?id=AT5G52360). GDP dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) are key regulators of Rho GTPase function [52]. Amino acid sequence identity was 78% between GDI2 and GDI, and neither of them had a signal peptide. GDI2 was predicted to be a non-classical secreted protein, but GDI was predicted to be an intracellular protein. As shown in Fig. 3, the fluorescence of the ADF10 and the GDI2 YFP fusion proteins could be detected in the cell wall after plasmolysis. These experimental results were consistent with the predictions and indicated that the bioinformatics predictions were reliable to some extent.

Table 1.

Differentially Expressed Proteins during Arabidopsis thaliana pollen germination were Identified by LC-MS/MS

| Spot numbera |

Accession number |

Protein homologue | Best expect valueb |

Locationc | p valued | Ratioe | Pollen expressf |

Multispotsg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate and energy metabolic process | ||||||||

| 44 | AT1G53240 | malate dehydrogenase (NAD) | 0.045 | Cell wall | 0.008 | 1.56 | Yes | |

| 17 | AT3G08590 | phosphoglyceromutase, putative | 1.60E-05 | Apoplast | 0.0091 | 1.69 | Yes | 19 |

| 37 | AT1G79550 | PGK (PHOSPHOGLYCERATE KINASE) | 0.0093 | Apoplast | 0.0017 | 1.75 | Yes | |

| 42 | AT3G15020 | malate dehydrogenase (NAD), mitochondrial, putative | 0.00012 | Apoplast | 0.0032 | 1.52 | Yes | 45 |

| 2 | AT2G26080* | Glycine dehydrogenase | 8.20E-07 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0018 | 1.76 | Yes | 3 |

| 18 | AT1G09780# | 2,3-biphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase, putative | 8.20E-05 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0034 | 2.47 | Yes | |

| 20 | AT3G17240 | dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase | 3.70E-06 | Mito. | 0.001 | 1.47 | Yes | |

| 16 | AT1G70730* | phosphomutase, putative | 2.00E-05 | Cyto. | 0.002 | 1.77 | Yes | |

| 38 | AT3G17940 | Aldose epimerase family protein | 3.10E-04 | Cyto. | 0.00082 | 1.86 | Yes | |

| 65 | AT5G26667@ | cytidylate kinase | 2.60E-06 | Cyto. | 0.01 | −2.38 | No | |

| 40 | AT5G43330 | malate dehydrogenase, cytosolic, putative | 0.0049 | Cyto. | 0.0017 | 1.4 | Yes | |

| 49 | AT5G50850 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase | 1.0e-4 | Cyto. | 0.0029 | 1.7 | Yes | 49 |

| 91 | AT4G35650 | isocitrate dehydrogenase, putative | 0.000015 | Cyto. | 0.0023 | −4.73 | Yes | 91 |

| Cell wall modifying and metabolism | ||||||||

| 43 | AT5G07410* | Pectinesterase PPME1 | 2.20E-06 | Cell wall | 0.0067 | 1.42 | Yes | 46, 47 |

| 6 | AT5G58170* | glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase family protein | 2.70E-07 | Cell wall | 0.0075 | 2.2 | Yes | 10, 11 |

| 13 | AT5G58050* | glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase family protein | 1.70E-08 | Cell wall | 0.0014 | 1.62 | Yes | |

| 58 | AT1G29140* | pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein | 0.016 | Cell wall | 0.00015 | 1.91 | Yes | |

| 71 | AT4G24640#@ | Pectinesterase inhibitor | 9.80E-05 | Apoplast | 0.0071 | 1.75 | Yes | |

| 62 | AT3G23600* | Dienelactone hydrolase family protein | 2.50E-08 | Apoplast | 0.01 | 1.73 | Yes | |

| 83 | AT5G39320# | UDP-glucose dehydrogenase | 4.40E-08 | Secrete | 1.40E-04 | 1.9 | Yes | |

| 77 | AT4G36230** | Putative glycine-rich cell wall protein | 0.045 | Secrete | 0.003 | 1.3 | Yes | |

| 54 | AT3G11210* | GDSL esterase/lipase CPRD49 | 7.8e-7 | Secrete | 0.0014 | 2.04 | Yes | |

| 51 | AT1G63000 | NRS/ER (NUCLEOTIDE-RHAMNOSE SYNTHASE/EPIMERASE-REDUCTASE) | 3.40E-07 | Nuc. | 0.0052 | 2.11 | Yes | 53 |

| Cytoskeleton | ||||||||

| 32 | At5g44340 | TUB4 (tubulin beta-4 chain) | 1.70E-05 | Cell wall | 0.0011 | 3.05 | Yes | |

| 27 | AT5G19770* | TUA3 (tubulin alpha-3) | 0.0016 | Cell wall | 0.0082 | 1.89 | Yes | |

| 89 | AT2G19760 | PFN1/PRF1 (PROFILIN 1) | 7.60E-06 | Cell wall | 0.0015 | −4.41 | Yes | |

| 36 | AT3G53750 | ACT3 | 1.90E-05 | Cell wall | 0.0078 | 1.71 | No | |

| 88 | AT4G29340 | PRF4 (PROFILIN 4) | 1.20E-06 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0019 | −4.61 | Yes | 94, 98 |

| 76 | AT5G52360 | actin-depolymerizing factor, putative ADF10 | 1.20E-06 | Apoplast | 7.60E-04 | −3.49 | Yes | 78, 85, 82 |

| Protein metabolism | ||||||||

| 5 | AT3G09840 | Cell division control protein 48 homolog A | 3.90E-07 | Cell wall | 0.0029 | 1.9 | Yes | |

| 33 | AT3G13920 | EIF4A1 | 1.90E-06 | Cell wall | 0.0014 | 1.56 | Yes | 34, 35 |

| 9 | AT3G12580* | HSP70 | 0.0075 | Cell wall | 0.002 | 1.89 | Yes | 12 |

| 1 | AT3G19170 | metalloendopeptidase | 0.0023 | Apoplast | 8.90E-05 | 2.19 | Yes | |

| 14 | AT5G02500 | HSC70-1 | 1.40E-08 | Apoplast | 0.0053 | 1.75 | Yes | |

| 61 | AT1G06260** | cysteine proteinase, putative | 7.80E-04 | Apoplast | 0.00036 | −10.41 | Yes | 63 |

| 8 | AT5G17920 | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-h omocysteine S-methyltransferase/methionine synthase | 1.40E-09 | Apoplast | 0.0075 | 1.16 | No | 90 |

| 50 | AT3G09200 | 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPP0B) | 1.10E-04 | Non-classical secreted | 0.0013 | 1.21 | Yes | |

| 64 | AT3G60820 | peptidase/ threonine-type endopeptidase | 9.30E-07 | Non-classical secreted | 0.00092 | −1.47 | Yes | |

| 7 | AT4G24190* | Hsp90.7 | 7.10E-04 | ER. | 0.0028 | 1.82 | Yes | |

| 25 | AT1G56340# | calreticulin 1 (CRT1) | 7.70E-04 | ER. | 0.0045 | 1.6 | Yes | 28 |

| 30 | AT1G09210 | calreticulin 2 (CRT2) | 1.6E-07 | ER. | 0.0033 | 1.97 | Yes | |

| 4 | AT1G56070 | LOS1 | 0.017 | Cyto. | 0.0019 | 2.18 | Yes | 4 |

| Signal transduction | ||||||||

| 15 | AT1G78900 | Proton-transporting ATPase | 0.00028 | Cell wall | 0.0013 | 1.67 | Yes | |

| 81 | AT4G38740 | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 1.40E-06 | Apoplast | 0.0001 | 5.32 | Yes | |

| 39 | AT1G35720@ | ANNAT1 (ANNEXIN ARABIDOPSIS 1); calcium ion binding | 4.40E-05 | Apoplast | 0.01 | 1.85 | Yes | |

| 21 | AT3G59920 | RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor | 2.50E-08 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.01 | 1.91 | Yes | |

| 41 | AT5G24940* | protein phosphatase 2C, putative | 0.012 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0016 | −1.35 | Yes | |

| 48 | AT5G65020 | ANNAT2 (ANNEXIN ARABIDOPSIS 2); calcium ion binding | 1.80E-09 | Cyto. | 0.0011 | 3.37 | Yes | |

| 57 | AT1G23140 | C2 domain-containing protein | 1.20E-04 | PM. | 0.0017 | −1.42 | Yes | |

| 23 | AT5G09550 | RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor | 4.00E-06 | Cyto. | 0.0084 | 2.07 | Yes | 24, 29 |

| Stress respond | ||||||||

| 79 | AT4G39260 | ATGRP8/GR-RBP8 (GLYCINE-RICH PROTEIN 8) | 1.70E-05 | Cell wall | 0.0039 | −3.22 | Yes | |

| 66 | AT3G05930 | GLP8 (GERMIN-LIKE PROTEIN 8) | 2.6e-7 | Apoplast | 0.0028 | −3.18 | Yes | |

| 70 | AT3G56240* | Copper homeostasis factor | 2.30E-07 | Secreted | 0.00034 | −3.39 | Yes | |

| 75 | AT2G46140* | L ate embryogenesis abundant protein, putative | 0.0017 | Secreted | 0.0029 | −4.11 | Yes | |

| 97 | AT5G40370 | glutaredoxin, putative | 8.10E-06 | Secreted | 0.002 | −5.14 | Yes | |

| 80 | AT2G21660 | ATGRP7 | 4.20E-04 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0036 | −1.49 | Yes | |

| 68 | AT4G11600 | ATGPX6 (GLUTATHIONE PEROXIDASE 6); | 5.00E-05 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.0027 | −4.12 | Yes | 69 |

| 93 | AT1G45145* | ATTRX5 (thioredoxin H-type 5) | 0.0000084 | Cyto. | 0.00042 | −4.08 | Yes | |

| 95 | AT3G51030 | Solution Structure Of Thioredoxin H1 | 1.60E-04 | Cyto. | 0.00084 | −4.26 | Yes | |

| Unknow | ||||||||

| 73 | AT5G18440** | unknown protein | 0.017 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.00023 | 11.23 | Yes | |

| 55 | AT4G31200** | surp domain-containing protein | 0.043 | Non-classical Secreted | 0.001 | 2.09 | Yes | |

| 96 | AT4G13560# | UNE15 (unfertilized embryo sac 15) | 8.20E-07 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.00052 | −5.03 | Yes | |

| 59 | AT1G36940** | unknown protein | 0.0074 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.0024 | −1.33 | Yes | |

| 67 | AT2G39435** | unknown protein | 0.043 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.0027 | 2.37 | No | |

| 56 | AT2G24070** | unknown protein | 0.022 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.0034 | −3.55 | Yes | |

| 92 | AT1G15415 | Unknown protein | 2.30E-05 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.00085 | −22.74 | No | |

| 72 | AT3G47833 | unknown | 0.004 | Cyto | 0.0017 | −1.38 | Yes | |

| Miscellaneous | ||||||||

| 52 | AT1G55040** | Zinc finger (Ran-binding) family protein | 0.0093 | Non-classical Secreted. | 0.0012 | 1.53 | Yes | 60, 74, 84 |

| 22 | AT4G13940 | MEE58 (MATERNAL EFFECT EMBRYO ARREST 58) | 1.10E-06 | Cyto. | 0.0015 | 3.21 | Yes | 26, 31 |

| 87 | AT5G57160 | ATLIG4 | 0.033 | Cyto. | 0.00034 | −4.63 | Yes | |

| 86 | AT2G25660** | EMB2410 (EMBRYO DEFECTIVE 2410) | 0.049 | Chlo. | 0.00027 | −3.17 | Yes | |

The spots number corresponds to the position number in BVA module of Decyder software.

The best expect value (e-value) represent the cofidence of the identified proteins (e-value <0.05).

The abbreviation represent: Cyto. cytoplasm, Chlo. chloroplast, Mito. mitochondria, PM. plasmalemma, ER. endoplasmic reticulum, Nuc. nucleus.

T-test indicates significant difference expression of these proteins during pollen germination.

Spot volume ratio between mature and germinated pollen.

Proteins present on 2-D gel as multispots.

Proteins were first identified from A. thaliana pollen,

proteins were first identified by using 2-DE approaches,

proteins were identical with A. thaliana pollen comparative proteome [28].

proteins identical with canola comparative proteome[29].

Fig. 3. Subcellular localizations of randomly selected proteins by transient expression of YFP fusion proteins.

YFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed into onion epidermal cells. The upper two rows are the empty YFP vector (negative control) before and after plasmolysis. The other three panels illustrate the localizations of the selected YFP fusion proteins after plasmolysis has occurred. The arrow indicates the cell wall of the onion epidermal cells. Overlaid images are shown for each transformation. Bar equals 100 µm.

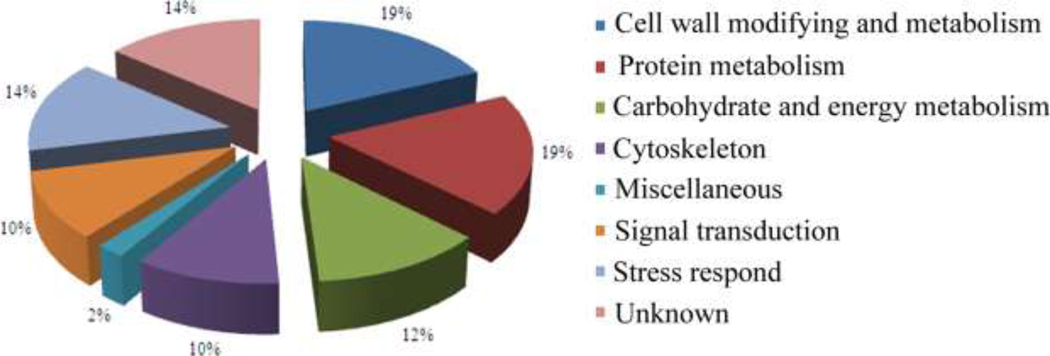

3.5. Functional categories of apoplastic proteins

According to the Go annotation of TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org/) and in combination with the metabolic features of pollen germination and pollen tube growth, the differentially expressed identities were classified into 8 categories, which included carbohydrate and energy metabolism, protein metabolism, cell wall modification and metabolism, stress response, cytoskeleton dynamics and signal transduction (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Functional categories of differentially expressed apoplastic proteins.

According to TAIR and UniProtKB Go annotation, differentially expressed protein were classified into eight categories.

Proteins involved in cell wall modification and metabolism were one of the largest groups of identified apoplastic proteins. Nine proteins, which accounted for 19% of the total, belonged to this category. These included dienelactone hydrolase family protein (spot 62), GDSL esterase (spot 54), pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein (spot 58), glycine-rich cell wall protein (spot 77), UDP-glucose dehydrogenase (spot 83), pectinesterase (spots 43, 46, 47) and pectinesterase inhibitor (spot 71). These proteins were also recognized as pollen wall or pollen-released proteins in rice, maize and canola [29, 33, 34]. In this study, these spots appeared more prominent after pollen germination. One of the highly abundant proteins identified in the apoplast was pectinesterase (spots 43, 46, 47). Pectinesterase is a key regulator of pectin, which is the major component of the pollen tube cell wall, especially at the pollen tube tip [53]. This regulation contributes to the oscillatory growth pattern of the pollen tube [53]. Reduction of pectinesterase activity results in abnormal pollen tube growth [19, 54]. It was interesting that the pectin esterase (spots 43, 46, 47) identified in this study was homologous to the AtPPME1, which plays an essential role in pollen tube growth. Pollen germination and pollen tube growth require loosening of the stigma wall and style transmitting tract, and beta-expansin is thought to involved in this process [55]. Pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein (spot 58) is a beta-expansin-like protein, it appeared more prominent after pollen germination,, which is in accordance with the requirement for accelerated pollen tube growth in the transmitting tract. Dienelactone hydrolase family protein has an endo-1,3-1,4-beta-D-glucanase activity that might be involved in the degradation of polysaccharose, which accumulates on the surface of stigmatic papillae [56]. Accelerated pollen tube growth is also required for active cell wall synthesis. Glycine-rich cell wall protein and UDP-glucose dehydrogenase are thought to be involved in this process. Previous work indicated the functional disruption of UDP-glucose dehydrogenase caused the cell wall to thin [57].

The differentially expressed proteins also showed a functional skew toward protein metabolism. In our study, 19% of the apoplastic proteins were involved in protein metabolism. These proteins were mainly involved in protein assembly and degradation, and most of them appeared more prominent after pollen germination. The temporal regulation of protein function is vital for pollen germination. A vital mechanism for this regulation is 26S proteasome-based selective protein degradation. Inhibition of 26S proteasome activity results in the disruption of pollen germination [58]. Threonine-type endopeptidase PBF1 (spot 64) was the beta type-1 subunit of the 20s proteasome, which is the proteolytic core of the 26S proteasome. Another 20S proteasome, alpha 1, and the 26S proteosome regulatory subunit have also been defined in the Arabidopsis cell wall and the release proteins of mature rice pollen [34, 59]. The 20S proteasome also releases into the extracellular space in mammalian cells and is involved in oxidized protein degradation [60]. Many heat shock proteins (Hsps; spots 7, 9, 12, 14) were identified in this study, and they were all up-regulated. Previous work has proven that Hsps can be secreted into the extracellular space in mammalian cells and play important roles in innate and antigen-specific immunity. Thus, they protect cells from cytotoxicity [61, 62]. In plants, Hsps have also been identified in the apoplasts of pea root tips and in the release proteins of mature rice pollen [34, 63].

Proteins involved in signal transduction processes are necessary between male and female gametophytes to successfully complete fertilization. In this study, 5 proteins, which accounted for 10% of the apoplastic proteins, were involved in signal transduction during pollen germination and pollen tube growth. An annexin protein ANNAt1 (spot 39) was included in the results and appeared more prominent after pollen germination. A significant amount of research has defined the role of ANNAt1 in the apoplast [34, 64]. Previous work has demonstrated that ANNAt1 localizes to the pollen tube tip and is proposed to play important roles in transmitting Ca2+ signals during pollen germination and pollen tube growth [65]. We also identified a RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor GDI2 (spot 21) in the apoplast. Many RAB GDP-dissociation inhibitor isoforms have been identified from the released proteins of mature rice pollen [34]. GDI2 appeared more prominent after pollen germination, which suggests it might play important roles during pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

Proteins that involved in stress response were also identified. They took 14% and all of them down-regulated during pollen germination. Mature pollen, being crucial organ for flowering plants, had developed sophisticated mechanisms to protect themselves and response to ever-changing biotic and abiotic environmental factors, one of the critical biological systems involved is secreting stress respond proteins. In our study, we identified GLP8 (spot 66), glutaredoxin (spot 97), ATGPX6 (spots 68, 69) and so on. In addition, we found that pollen germination related apoplastic proteins were also involved in the cytoskeleton and energy metabolic process.

It’s interesting, there are six functional unknown proteins were identified in our study, most of them were non-classical secreted proteins. Some of them had a drastic change during pollen germination (spots 73, 92), that indicated they might play essential roles during pollen germination by some unknown functions. UNE15 had been proved to play important roles in guiding the pollen tube by mutant screening [66], however, the mechanism was unknown. In this study, we identified UNE15 in the pollen apoplast, it was down-regulated during pollen germination. This will be helpful to understand how the proteins fulfill the function of guiding the pollen tube.

3.6. Comparisons of our results with the results of other studies

There are several studies about the A. thaliana mature pollen proteome, and many proteins were identified by using 2-DE or shotgun method [23, 26, 67, 68]. We compared our results with all of the other A. thaliana pollen proteome studies, and found nine proteins were specifically identified in our results (Table 1). Using a shotgun proteomics approach, Grobei et. al unambiguously identified about ~3,500 proteins in Arabidopsis pollen[26]. However, if only compared with the proteome results that based on 2-DE approaches, there were 28 proteins were first identified in our results (Table 1). There are two comparative proteome studies about the differentially expressed proteins during pollen germination [29, 49]. Both of them analyzed the total proteins of pollen. In canola pollen, 164 proteins spots were significantly changed during germination, 130 spots were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF, represent 80 proteins. Compared with our results, only five proteins were both identified in these studies (Table 1). In another study of the A. thaliana pollen, 40 protein spots were significant changed and 21 proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF MS, only three proteins were the same with our results (Table 1). These results indicated it was necessary to study of apoplast proteome, and apoplastic proteins took part in the pollen germination in a specific way, that was different with cytoplastic proteins.

The transcriptome changes in A. thaliana pollen germination have been analyzed. By comparing with the transcriptome of Arabidopsis pollen during pollen germination[39], we found 46 genes were present both in protein and mRNA level, however, only 13 genes were significant changed both in protein and mRNA level. Seven proteins expression correlation with the corresponding mRNA level (Table 1, Spot 9, 25, 41, 96, 42, 33, 14) and six genes have the inverse tendency (Table 1, Spot 2, 49, 54, 79, 69, 93). The low correlation between protein abundance and mRNA amount for some protein spots may be due to the dependence of protein expression levels not only depended on the corresponding mRNA levels but also on the regulation by translation and protein degradation systems. Furthermore, protein abundance in the apoplastic compartment of plant cells was also affected by secretory pathways and transport systems. The low correlation between protein and mRNA level was also found in other pollen germination work [23]. By reference to the available microarray data [39, 69], five proteins’ mRNAs were missing in microarray data (Table 1). These proteins might be released from the tapetum not encoded by the gametophyte, or, the expression of these genes were too low and didn’t identified by microarray [24]. In the shotgun proteomics study of A. thaliana pollen, authors also identified 537 proteins that were not identified in genetic or transcriptomic studies[26].

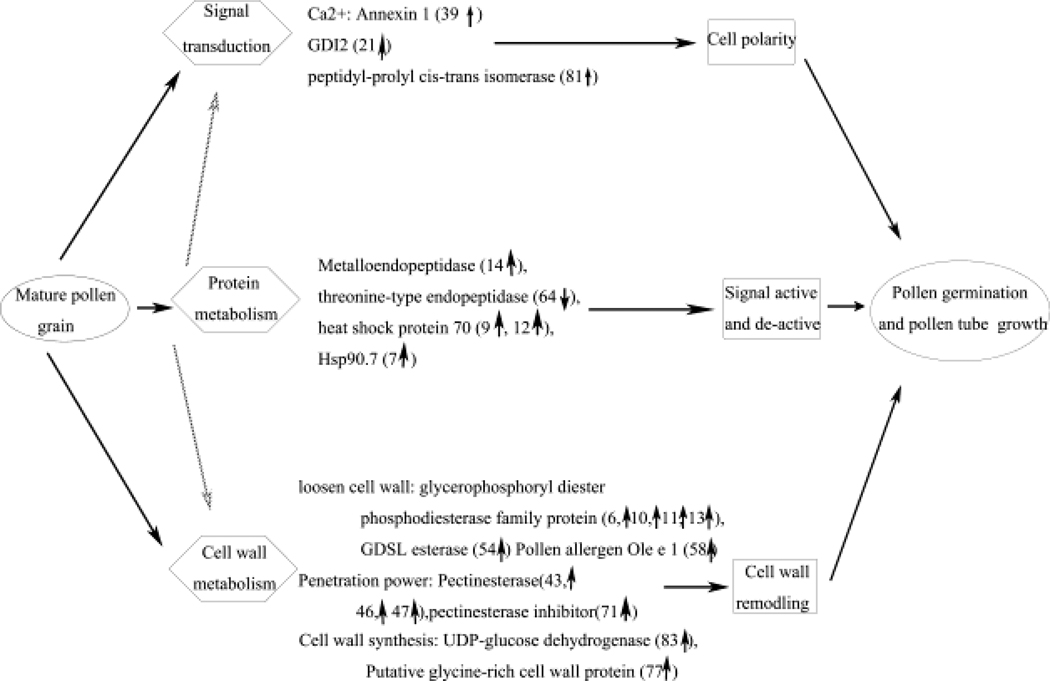

3.7. A proposed protein network: apoplastic proteins participate in pollen germination and pollen tube growth

Mature A. thaliana pollen grains are dry desiccated structures. When they land on stigma or optimized medium, their cellular metabolism rapidly activates, and their cell morphology quickly changes. The apoplast is the first subcellular component to receive signals and is also important in preserving cell morphology; therefore, it has important roles in pollen functions. Based on the proteomic results of this study, we propose an apoplastic protein network involved in the mechanisms of pollen germination and pollen tube growth (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. A proposed protein network: apoplastic proteins participate in pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

Based on the functional categories of the apoplastic proteins, a protein network was proposed to explain the role of the apoplastic proteins during pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

After pollen hydration, the apoplast responds quickly to develop the polarity required for pollen germination. A lot of signal transduction involved in this process, such as calcium gradient, pH gradient, GTPase, annexins and so on [70]. Once the pollen tube protrudes from the cell, one side of the new cell wall has to be synthesized quickly. Glycine-rich cell wall protein and UDP-glucose dehydrogenase would be used to assemble this new cell wall. The other side of the cell wall of the stigma and the transmitting tract then has to be loosened. Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase, extensin family protein and esterase might play important roles in this process. Pectinesterase and pectinesterase inhibitor might contribute to regulate the penetrating power and maintain the oscillatory growth pattern of the pollen tube. The rapid growth of the pollen tube requires fast metabolic turnover of protein, signal regulation and cell wall metabolism during pollen germination also need protein fast metabolism. Proteins that involved in protein turnover, such as Hsps, 26S proteasome, might play important roles during pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

4. Conclusions

In this present study, we analyzed the global changes of the apoplast proteome during A. thaliana pollen germination and pollen tube growth using 2-D DIGE and LC-MS/MS. In the 2-D DIGE results, 103 spots were significantly differentially expressed after pollen germination, and 98 spots, which represented 71 proteins, were identified. After bioinformatic analyses, 50 proteins were found to be apoplastic proteins. Of these 50, 19% were involved in cell wall modification and protein metabolism. This is the first study investigating the apoplast proteome during pollen germination and pollen tube growth. Three proteins were randomly selected to determine their subcellular localizations. As predicted by the bioinformatics tools, two were localized to the cell wall, and the other was localized to the cytoplasm. Based on our functional analysis and the properties of pollen germination and pollen tube growth, we proposed a model that detailed the possible mechanisms for the apoplastic proteins in pollen germination and pollen tube growth. These data will help in better understanding the important roles of apoplastic proteins in complicated processes.

Supplementary Material

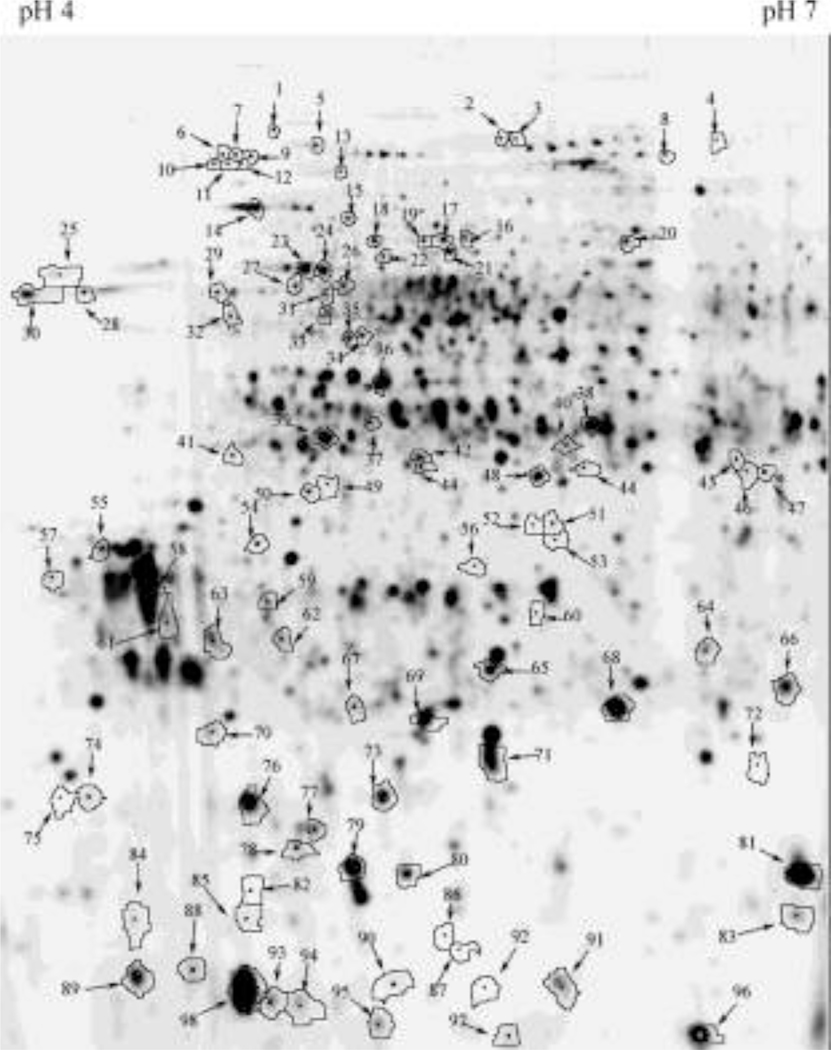

Fig. 2. A representative gel of significantly differentially expressed apoplastic proteins during pollen germination and pollen tube growth.

An equal amount (90µg) of apoplast proteins from mature and germinated Arabidopsis thaliana pollen were mixed and labeled with Cy3 for a preparative gel. Ninety-eight of 103 differentially expressed proteins were successfully identified. Position numbers corresponding to the spot numbers are listed in Table 1.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30870200, 31071245), the Key project of Chinese National Transgenic Program (Grant No. 2009ZX08009-017B), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (Grant No. 211019), the Hebei Province Foundation for Returned Scholars (Grant No. 20100327). The LC-MS/MS data was provided by the Bio-Organic Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Resource at UCSF (A.L. Burlingame, Director) supported by the Biomedical Research Technology Program of the NIH National Center for Research Resources, NIH NCRR (P41RR001614) and NIH NCRR (RR019934).

Appendices

Table A.1. The experiment design

Table A.2. The sequences of unique peptides used to identify the proteins

Figure A.1. Bulk collected pollen FDA staining and pollen germination on solid medium.

Figure A.2. Western blot assay to test the purity of apoplastic proteins

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pignocchi C, Foyer CH. Apoplastic ascorbate metabolism and its role in the regulation of cell signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:379–389. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Tian LH, Zhao JF, Song Y, Zhang CJ, Guo Y. Identification of an apoplastic protein involved in the initial phase of salt stress response in rice root by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:916–928. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz-Vivancos P, Rubio M, Mesonero V, Periago PM, Barcelo AR, Martinez-Gomez P, Hernandez JA. The apoplastic antioxidant system in Prunus: response to long-term plum pox virus infection. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:3813–3824. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian L, Zhang L, Zhang J, Song Y, Guo Y. Differential proteomic analysis of soluble extracellular proteins reveals the cysteine protease and cystatin involved in suspension-cultured cell proliferation in rice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hematy K, Cherk C, Somerville S. Host-pathogen warfare at the plant cell wall. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal GK, Jwa NS, Lebrun MH, Job D, Rakwal R. Plant secretome: unlocking secrets of the secreted proteins. Proteomics. 2010;10:799–827. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y, Zhang C, Ge W, Zhang Y, Burlingame AL, Guo Y. Identification of NaCl stress-responsive apoplastic proteins in rice shoot stems by 2D-DIGE. J Proteomics. 2011;74:1045–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakurai N. Dynamic function and regulation of apoplast in the plant body. Journal of Plant Research. 1998;111:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM. The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell. 1997;89:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schopfer CR, Nasrallah ME, Nasrallah JB. The male determinant of self-incompatibility in Brassica. Science. 1999;286:1697–1700. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearce G, Strydom D, Johnson S, Ryan CA. A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science. 1991;253:895–897. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5022.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lease KA, Walker JC. The Arabidopsis unannotated secreted peptide database, a resource for plant peptidomics. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:831–838. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamet E, Albenne C, Boudart G, Irshad M, Canut H, Pont-Lezica R. Recent advances in plant cell wall proteomics. Proteomics. 2008;8:893–908. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark NL, Aagaard JE, Swanson WJ. Evolution of reproductive proteins from animals and plants. Reproduction. 2006;131:11–22. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman LA, Goring DR. Pollen-pistil interactions regulating successful fertilization in the Brassicaceae. J Exp Bot. 2010;61:1987–1999. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung AY, Wu HM. Structural and signaling networks for the polar cell growth machinery in pollen tubes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:547–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayfield JA, Preuss D. Rapid initiation of Arabidopsis pollination requires the oleosin-domain protein GRP17. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:128–130. doi: 10.1038/35000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Updegraff EP, Zhao F, Preuss D. The extracellular lipase EXL4 is required for efficient hydration of Arabidopsis pollen. Sex Plant Reprod. 2009;22:197–204. doi: 10.1007/s00497-009-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang L, Yang SL, Xie LF, Puah CS, Zhang XQ, Yang WC, Sundaresan V, Ye D. VANGUARD1 encodes a pectin methylesterase that enhances pollen tube growth in the Arabidopsis style and transmitting tract. Plant Cell. 2005;17:584–596. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.027631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayama S, Shimosato H, Shiba H, Funato M, Che FS, Watanabe M, Iwano M, Isogai A. Direct ligand-receptor complex interaction controls Brassica self-incompatibility. Nature. 2001;413:534–538. doi: 10.1038/35097104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escobar-Restrepo JM, Huck N, Kessler S, Gagliardini V, Gheyselinck J, Yang WC, Grossniklaus U. The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science. 2007;317:656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCormick S. Plant science. Reproductive dialog. Science. 2007;317:606–607. doi: 10.1126/science.1146655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes-Davis R, Tanaka CK, Vensel WH, Hurkman WJ, McCormick S. Proteome mapping of mature pollen of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics. 2005;5:4864–4884. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200402011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noir S, Brautigam A, Colby T, Schmidt J, Panstruga R. A reference map of the Arabidopsis thaliana mature pollen proteome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheoran IS, Sproule KA, Olson DJH, Ross ARS, Sawhney VK. Proteome profile and functional classification of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana (Landsberg erecta) mature pollen. Sexual Plant Reproduction. 2006;19:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grobei MA, Qeli E, Brunner E, Rehrauer H, Zhang R, Roschitzki B, Basler K, Ahrens CH, Grossniklaus U. Deterministic protein inference for shotgun proteomics data provides new insights into Arabidopsis pollen development and function. Genome research. 2009;19:1786. doi: 10.1101/gr.089060.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernando DD. Characterization of pollen tube development in Pinus strobus (Eastern white pine) through proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins. Proteomics. 2005;5:4917–4926. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou J, Song L, Zhang W, Wang Y, Ruan S, Wu WH. Comparative proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis mature pollen and germinated pollen. J Integr Plant Biol. 2009;51:438–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2009.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheoran IS, Pedersen EJ, Ross AR, Sawhney VK. Dynamics of protein expression during pollen germination in canola (Brassica napus) Planta. 2009;230:779–793. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pertl H, Schulze WX, Obermeyer G. The pollen organelle membrane proteome reveals highly spatial-temporal dynamics during germination and tube growth of lily pollen. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:5142–5152. doi: 10.1021/pr900503f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dai S, Chen T, Chong K, Xue Y, Liu S, Wang T. Proteomics identification of differentially expressed proteins associated with pollen germination and tube growth reveals characteristics of germinated Oryza sativa pollen. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:207–230. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600146-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayfield JA, Fiebig A, Johnstone SE, Preuss D. Gene families from the Arabidopsis thaliana pollen coat proteome. Science. 2001;292:2482–2485. doi: 10.1126/science.1060972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suen DF, Wu SS, Chang HC, Dhugga KS, Huang AH. Cell wall reactive proteins in the coat and wall of maize pollen: potential role in pollen tube growth on the stigma and through the style. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43672–43681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai S, Li L, Chen T, Chong K, Xue Y, Wang T. Proteomic analyses of Oryza sativa mature pollen reveal novel proteins associated with pollen germination and tube growth. Proteomics. 2006;6:2504–2529. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alban A, David SO, Bjorkesten L, Andersson C, Sloge E, Lewis S, Currie I. A novel experimental design for comparative two-dimensional gel analysis: two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis incorporating a pooled internal standard. Proteomics. 2003;3:36–44. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson-Brousseau SA, McCormick S. A compendium of methods useful for characterizing Arabidopsis pollen mutants and gametophytically-expressed genes. Plant J. 2004;39:761–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heslop-Harrison J, Heslop-Harrison Y. Evaluation of pollen viability by enzymatically induced fluorescence; intracellular hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate. Stain Technol. 1970;45:115–120. doi: 10.3109/10520297009085351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boavida LC, McCormick S. Temperature as a determinant factor for increased and reproducible in vitro pollen germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007;52:570–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Zhang WZ, Song LF, Zou JJ, Su Z, Wu WH. Transcriptome analyses show changes in gene expression to accompany pollen germination and tube growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1201–1211. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenfeld J, Capdevielle J, Guillemot JC, Ferrara P. In-gel digestion of proteins for internal sequence analysis after one- or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1992;203:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90061-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chalkley RJ, Baker PR, Medzihradszky KF, Lynn AJ, Burlingame AL. In-depth analysis of tandem mass spectrometry data from disparate instrument types. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2008;7:2386–2398. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800021-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clauser KR, Baker P, Burlingame AL. Role of accurate mass measurement (+/− 10 ppm) in protein identification strategies employing MS or MS/MS and database searching. Anal Chem. 1999;71:2871–2882. doi: 10.1021/ac9810516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balgley BM, Laudeman T, Yang L, Song T, Lee CS. Comparative evaluation of tandem MS search algorithms using a target-decoy search strategy. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2007;6:1599–1608. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600469-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bendtsen JD, Jensen LJ, Blom N, Von Heijne G, Brunak S. Feature-based prediction of non-classical and leaderless protein secretion. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:349–356. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agrawal GK, Jwa NS, Lebrun MH, Job D, Rakwal R. Plant secretome: unlocking secrets of the secreted proteins. Proteomics. 10:799–827. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haynes PA, Roberts TH. Subcellular shotgun proteomics in plants: looking beyond the usual suspects. Proteomics. 2007;7:2963–2975. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu J, Chen S, Alvarez S, Asirvatham VS, Schachtman DP, Wu Y, Sharp RE. Cell wall proteome in the maize primary root elongation zone. I. Extraction and identification of water-soluble and lightly ionically bound proteins. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:311–325. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kong FJ, Oyanagi A, Komatsu S. Cell wall proteome of wheat roots under flooding stress using gel-based and LC MS/MS-based proteomics approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1804:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casasoli M, Spadoni S, Lilley KS, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G, Mattei B. Identification by 2-D DIGE of apoplastic proteins regulated by oligogalacturonides in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proteomics. 2008;8:1042–1054. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CY, Wong EI, Vidali L, Estavillo A, Hepler PK, Wu HM, Cheung AY. The regulation of actin organization by actin-depolymerizing factor in elongating pollen tubes. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2175–2190. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DerMardirossian C, Bokoch GM. GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosch M, Hepler PK. Pectin methylesterases and pectin dynamics in pollen tubes. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3219–3226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tian GW, Chen MH, Zaltsman A, Citovsky V. Pollen-specific pectin methylesterase involved in pollen tube growth. Dev Biol. 2006;294:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valdivia ER, Stephenson AG, Durachko DM, Cosgrove D. Class B beta-expansins are needed for pollen separation and stigma penetration. Sex Plant Reprod. 2009;22:141–152. doi: 10.1007/s00497-009-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shakya R, Bhatla SC. A comparative analysis of the distribution and composition of lipidic constituents and associated enzymes in pollen and stigma of sunflower. Sex Plant Reprod. 2010;23:163–172. doi: 10.1007/s00497-009-0125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reboul R GC, Luetz-Meindl U, Tenhaken R. Influence of reduced UDP-glucose dehydrogenase activity on Arabidopsis thaliana: new cell wall mutants; 20TH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ARABIDOPSIS RESEARCH; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Speranza A, Scoccianti V, Crinelli R, Calzoni GL, Magnani M. Inhibition of proteasome activity strongly affects kiwifruit pollen germination. Involvement of the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway as a major regulator. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1150–1161. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bayer EM, Bottrill AR, Walshaw J, Vigouroux M, Naldrett MJ, Thomas CL, Maule AJ. Arabidopsis cell wall proteome defined using multidimensional protein identification technology. Proteomics. 2006;6:301–311. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sixt SU, Dahlmann B. Extracellular, circulating proteasomes and ubiquitin - incidence and relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1782:817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calderwood SK, Mambula SS, Gray PJ., Jr Extracellular heat shock proteins in cell signaling and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:28–39. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein-based novel immunotherapies. Drug News Perspect. 2000;13:517–522. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2000.13.9.858479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wen F, VanEtten HD, Tsaprailis G, Hawes MC. Extracellular proteins in pea root tip and border cell exudates. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:773–783. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaffarnik FA, Jones AM, Rathjen JP, Peck SC. Effector proteins of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae alter the extracellular proteome of the host plant. Arabidopsis thaliana, Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:145–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800043-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mortimer JC, Laohavisit A, Macpherson N, Webb A, Brownlee C, Battey NH, Davies JM. Annexins: multifunctional components of growth and adaptation. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:533–544. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pagnussat GC, Yu HJ, Ngo QA, Rajani S, Mayalagu S, Johnson CS, Capron A, Xie LF, Ye D, Sundaresan V. Genetic and molecular identification of genes required for female gametophyte development and function in Arabidopsis. Development. 2005;132:603–614. doi: 10.1242/dev.01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noir S, Brautigam A, Colby T, Schmidt J, Panstruga R. A reference map of the Arabidopsis thaliana mature pollen proteome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Inder S Sheoran KAS, Olson Douglas JH, Ross Andrew RS, Sawhney Vipen K. Proteome profile and functional classification of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana (Landsberg erecta) mature pollen. Sex Plant Reprod. 2006;19:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- 69.NASCArrays Experiment: AtGenExpress: Developmental Series (flowers and pollen) http://128.243.111.177/narrays/experimentpage.pl?experimentid=152. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holdaway-Clarke TL, Weddle NM, Kim S, Robi A, Parris C, Kunkel JG, Hepler PK. Effect of extracellular calcium, pH and borate on growth oscillations in Lilium formosanum pollen tubes. J Exp Bot. 2003;54:65–72. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.