Abstract

AIM: To investigate potential antitumor effects of rAd-p53 by determining if it enhanced sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy.

METHODS: Three gastric cancer cell lines with distinct levels of differentiation were treated with various doses of rAd-p53 alone, oxaliplatin (OXA) alone, or a combination of both. Cell growth was assessed with an 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo (-z-y1)-3,5-diphenytetrazoliumromide assay and the expression levels of p53, Bax and Bcl-2 were determined by immunohistochemistry. The presence of apoptosis and the expression of caspase-3 were determined using flow cytometry.

RESULTS: Treatment with rAd-p53 or OXA alone inhibited gastric cancer cell growth in a time- and dose-dependent manner; moreover, significant synergistic effects were observed when these treatments were combined. Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that treatment with rAd-p53 alone, OXA alone or combined treatment led to decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased Bax expression in gastric cancer cells. Furthermore, flow cytometry showed that rAd-p53 alone, OXA alone or combination treatment induced apoptosis of gastric cancer cells, which was accompanied by increased expression of caspase-3.

CONCLUSION: rAd-p53 enhances the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy by promoting apoptosis. Thus, our results suggest that p53 gene therapy combined with chemotherapy represents a novel avenue for gastric cancer treatment.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, rAd-p53, Oxaliplatin, Chemosensitivity, Apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the most common malignant tumor of the digestive system. Currently, the major therapeutic methods for the treatment of gastric cancer are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Despite recent improvements in these treatments, the 5-year survival rate for gastric cancer patients is only 45%. Thus, the development of new therapeutic approaches for gastric cancer, such as gene therapy, is urgently needed.

p53 is known as the “genome guard” and plays important roles in various cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, DNA damage repair and apoptosis. Genetic mutations in p53 are present in > 50% of human tumor tissues, and it is the most commonly detected genetic mutation in cancer[1]. Therefore, a gene therapy strategy has been developed that employs rAd-p53, a weakened adenovirus carrying the wild-type p53 gene. rAd-p53 has been shown to inhibit tumor growth, promote apoptosis by inducing the expression of Puma, Bax, Bak and Fas, and to sensitize tumor cells to radiotherapy and chemotherapy[2]. Clinical application of rAd-p53 has been used to treat lung cancer, breast cancer, oophoroma, liver cancer, and bladder carcinoma. However, few studies have investigated the therapeutic effects of rAd-p53 in gastric cancer.

Genetic mutation of p53 is found in > 60% of gastric cancer cases and has been shown to correlate not only with the onset and prognosis of gastric cancer, but also with the chemosensitivity of gastric cancer[3]. Thus, we speculated that rAd-p53 could be a potential treatment for gastric cancer. In this study, we investigated the effects of rAd-p53 treatment alone or in combination with oxaliplatin (OXA) on the growth and chemosensitivity of gastric cancer cells. Our results demonstrate that rAd-p53 has antitumor properties in gastric cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

rAd-p53 was purchased from Shenzhen Saibainuo Gene Technology Co. Ltd. (Shenzhen, China); OXA was purchased from Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co. Ltd. (Lianyungang, China). rAd-p53 was diluted to 5 × 108 virus particles vp/mL or 5 × 1010 vp/mL in saline, and OXA was diluted to 2.5 mg/mL in 5% glucose and stored at -80 °C.

Cell culture

The human gastric cancer lines SGC-7901 (moderately differentiated), BGC-823 (poorly differentiated), and HGC-27 (undifferentiated) were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China). The cells were cultured in XX media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 105 U/L penicillin, and 100 ng/L streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

MTT assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 104 cells/well and treated with rAd-p53 or OXA for 24, 48 or 72 h at 37 °C. Next, 150 μL MTT was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, followed by addition of 200 μL dimethyl sulfoxide to each well, and 10 min incubation to dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured using an ELISA reader (EXL800; Bio-Tek, United States) at 450 nm. The data are presented as mean ± SD of triplicate samples from at least three independent experiments.

The cell growth inhibition ratio was calculated using the following formula: cell growth inhibition ratio (%) = 1 - [(As - Ab/(Ac - Ab)]× 100%, where As represents the A value of the experimental well, Ac represents the A value in the control well, and Ab represents the A value of the blank well.

To determine whether rAd-p53 and OXA had synergistic effects, the following formula was used: q = (Ea + b)/[(Ea + Eb) - Ea × Eb], where Ea represent the inhibition ratio of rAd-p53, Eb represents the inhibition ratio of OXA, and Ea + b represents the inhibition ratio of the associated group. A q value > 1.15 was considered to indicate a synergistic effect, whereas a q value < 0.85 was considered to indicate a lack of a synergistic effect, and a q value between 0.85 and 1.15 was considered to indicate an additive effect.

Immunohistochemistry

Cells were seeded in six-well plates at 106 cells/well and then treated with rAd-p53 or OXA for 24 h. The cells were fixed with acetone for 20 min and then stained using an SP immunohistochemistry kit (Zhongshanqiao, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In the gastric cancer cells examined, p53 expression was nuclear, whereas Bcl-2 and Bax expression were located in the cytoplasm.

Flow cytometry analysis

Cells were seeded in six-well plates at 5 × 105 cells/well and then treated with rAd-p53 or OXA for 24 h. Apoptotic cells were detected with an apoptosis detection kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, United States).

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0. Single factor analysis of variance, least significant difference methods, and Q tests were used for inside group comparisons, group comparisons, and multiple comparisons, respectively. For all analyses, the test size was set to α = 0.05. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Treatment with rAd-p53 or OXA inhibits the growth of gastric cancer cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner

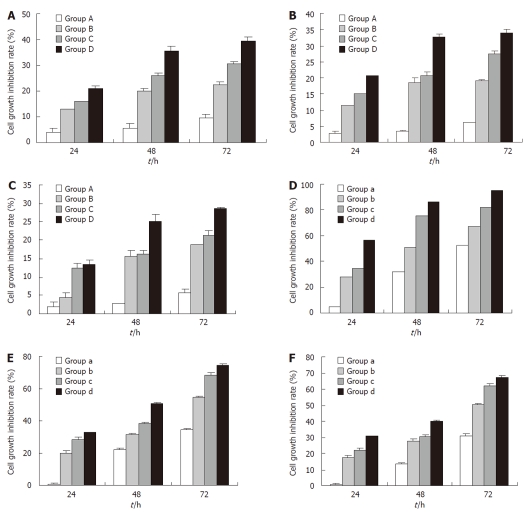

The MTT assay results showed that rAd-p53 could inhi-bit the growth of the gastric cancer cell lines SGC-7901 (moderately differentiated), BGC-823 (poorly differentiated) and HGC-27 (undifferentiated) in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A-C). A similar result was observed for OXA treatment (Figure 1D-F). Among the three cell lines, we found that the inhibitory effects of rAd-p53 and OXA were both strongest in SGC-7901 and weakest in HGC-27 when treatment dose and time were kept constant, suggesting that more differentiated gastric cancer cells are more sensitive to rAd-p53 and OXA treatments.

Figure 1.

Treatment with rAd-p53 or oxaliplatin alone inhibits the growth of gastric cancer cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. SGC-7910 (A), BGC-823 (B) and HGC-27 (C) cells were treated with rAd-p53 followed by the determination of cell growth inhibition rates. Groups A, B, C and D were treated with the indicated rAd-p53 dose (vp/mL) of 5 × 106, 5 × 107, 5 × 108 and 5 × 109, respectively. SGC-7910 (D), BGC-823 (E) and HGC-27 (F) cells were treated with oxaliplatin (OXA), and cell growth inhibition rates were determined. Groups a, b, c and d were treated with the indicated OXA dose (μg/mL) of 3.2, 6.4, 12.8 and 25.6, respectively.

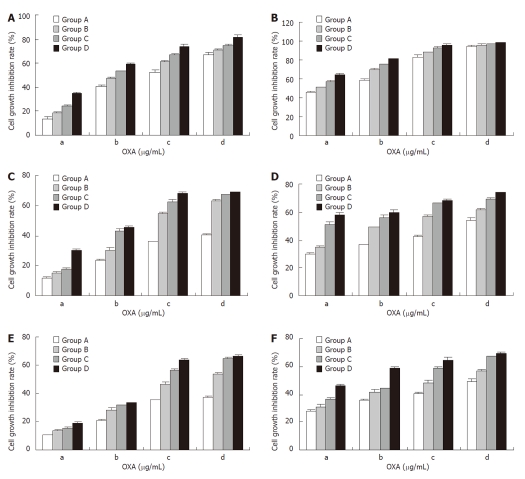

Combined treatment with rAd-p53 and OXA shows a synergistic effect on the inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth

We next used treated the three gastric cancer cell lines with a combination of rAd-53 and OXA and found that the inhibition of cell growth was markedly stronger at a relatively low combined dose and with a short treatment time (Figure 2), compared to treatment with rAd-p53 or OXA alone (Figure 1). A q value > 1.15 indicated that rAd-p53 and OXA had synergistic effects on the inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth.

Figure 2.

Combination treatment with rAd-p53 and oxaliplatin has synergistic effects on the inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth. SGC-7910 (A, B), BGC-823 (C, D) and HGC-27 (E, F) cells were treated with rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin (OXA), and cell growth inhibition rates were determined at 24 h (A, C, E) or 48 h (B, D, F). Groups A, B, C and D were treated with the indicated rAd-p53 dose (vp/mL) of 5 × 106, 5 × 107, 5 × 108 and 5 × 109, respectively. Groups a, b, c and d were treated with the indicated OXA dose (μg/mL) of 3.2, 6.4, 12.8 and 25.6, respectively.

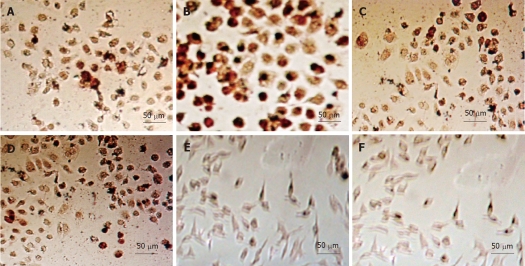

Expression of p53 in gastric cancer cells treated with rAd-p53 or OXA alone or with rAd-p53 in combination with OXA

As expected, when the gastric cancer cell lines were treated with rAd-p53 for 48 h, immunohistochemical staining showed that p53 expression increased gradually with respect to dose (Figure 3, Table 1). Moreover, when the same treatment doses were used, p53 expression was stronger in more differentiated gastric cancer cells. However, the combined use of OXA at 3.2 μg/mL and rAd-p53 had no obvious, additional effects on p53 expression, indicating that the antitumor effects of OXA were not related to the upregulation of p53 expression in tumor cells.

Figure 3.

Detection of p53 expression in gastric cancer cells with immunohistochemistry. A: Untreated SGC-7901 cells; B: SGC-7901 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL oxaliplatin (OXA); C: Untreated BGC-823 cells; D: BGC-823 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA; E: Untreated HGC-27 cells untreated; F: HGC-27 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA.

Table 1.

p53 expression in gastric cancer cells 48 h after treatment with rAd-p53, oxaliplatin or rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin

| Treatment | Gastric cancer cell line | ||||

| rAd-p53 (vp/mL) | OXA (μg/mL) | SGC-7901 | BGC-823 | HGC-27 | |

| OXA | 0 | 3.2 | 11.83 ± 1.02eb | 8.67 ± 1.35eb | 6.36 ± 1.62eb |

| rAd-p53 | 5 × 106 | 0 | 36.65 ± 1.04ca | 25.13 ± 2.73ca | 21.26 ± 1.07ca |

| 5 × 107 | 0 | 40.32 ± 1.03ca | 32.45 ± 2.35ca | 25.35 ± 1.28ca | |

| 5 × 108 | 0 | 48.86 ± 1.26ca | 38.25 ± 2.16ca | 29.67 ± 1.31ca | |

| 5 × 109 | 0 | 60.38 ± 1.14ca | 49.37 ± 1.07ca | 33.25 ± 2.05ca | |

| rAd-p53 + OXA | 5 × 106 | 3.2 | 37.23 ± 1.07eca | 26.54 ± 1.53eca | 22.17 ± 1.13eca |

| 5 × 107 | 3.2 | 39.83 ± 1.32eca | 34.17 ± 1.26eca | 24.83 ± 1.07eca | |

| 5 × 108 | 3.2 | 49.03 ± 1.26eca | 40.28 ± 1.43eca | 30.45 ± 1.32eca | |

| 5 × 109 | 3.2 | 61.54 ± 1.18eca | 50.37 ± 1.27eca | 35.21 ± 2.1eca | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 12.55 ± 1.15 | 8.23 ± 1.13 | 6.15 ± 1.36 |

P < 0.05 vs control,

P > 0.05 vs control;

P > 0.05, rAd-p53 vs rAd-p53 + oxaliplatin (OXA) with the same dose of rAd-p53;

P < 0.05, OXA vs rAd-p53 + OXA with the same dose of OXA.

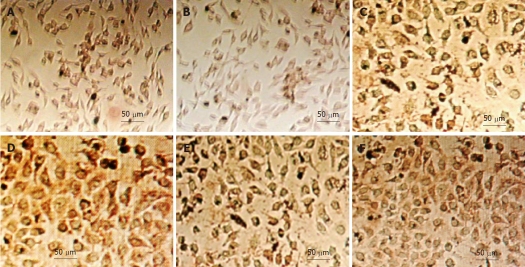

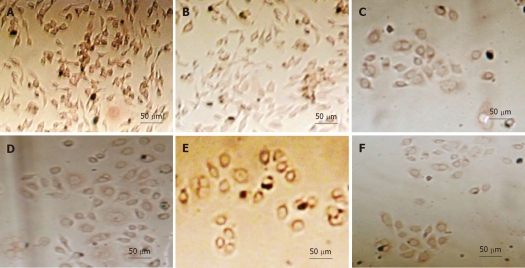

Expression of Bax and Bcl-2 in gastric cancer cells treated with rAd-p53 or OXA alone, or rAd-p53 in combination with OXA

Immunohistochemical staining also showed that the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax increased gradually in gastric cancer cells treated with increasing doses of rAd-p53 for 48 h (Figure 4, Table 2), whereas the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 decreased gradually (Figure 5, Table 3). Combination treatment with OXA at 3.2 μg/mL and rAd-p53 had modest effects on the levels of Bax and Bcl-2 expression, indicating that the antitumor effects of rAd-p53 and OXA were mediated by a mechanism that promoted gastric cancer cell apoptosis.

Figure 4.

Detection of bax expression in gastric cancer cells with immunohistochemistry. A: Untreated SGC-7901 cells; B: SGC-7901 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL oxaliplatin (OXA); C: Untreated BGC-823 cells; D: BGC-823 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA; E: Untreated HGC-27 cells; F: HGC-27 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA.

Table 2.

Bax expression in gastric cancer cells 48 h after treatment with rAd-p53, oxaliplatin or rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin

| Treatment | Gastric cancer cell line | ||||

| rAd-p53 (vp/mL) | OXA (μg/mL) | SGC-7901 | BGC-823 | HGC-27 | |

| OXA | 0 | 3.2 | 73.52 ± 0.83ea | 56.43 ± 0.74ea | 36.47 ± 1.21ea |

| rAd-p53 | 5 × 106 | 0 | 63.25 ± 1.32ca | 53.86 ± 1.54ca | 33.71 ± 1.41ca |

| 5 × 107 | 0 | 76.14 ± 0.73ca | 59.32 ± 1.45ca | 39.47 ± 1.03ca | |

| 5 × 108 | 0 | 79.62 ± 1.46ca | 64.74 ± 1.08ca | 41.35 ± 1.15ca | |

| 5 × 109 | 0 | 82.54 ± 1.28ca | 69.53 ± 1.02ca | 43.75 ± 1.1ca | |

| rAd-p53 + OXA | 5 × 106 | 3.2 | 78.82 ± 0.88eca | 58.64 ± 1.07eca | 49.15 ± 1.04eca |

| 5 × 107 | 3.2 | 84.32 ± 1.02eca | 62.74 ± 1.19eca | 52.9 ± 1.31eca | |

| 5 × 108 | 3.2 | 87.41 ± 1.03eca | 67.38 ± 1.14eca | 55.23 ± 1.06eca | |

| 5 × 109 | 3.2 | 89.71 ± 0.36eca | 75.14 ± 1.65eca | 58.67 ± 1.12eca | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 26.32 ± 1.04 | 19.91 ± 0.87 | 16.74 ± 1.23 |

P < 0.05 vs control;

P < 0.05, rAd-p53 vs rAd-p53 + oxaliplatin (OXA) with the same dose of rAd-p53;

P < 0.05, OXA vs rAd-p53 + OXA with the same dose of OXA.

Figure 5.

Detection of Bcl-2 expression in gastric cancer cells with immunohistochemistry. A: Untreated SGC-7901 cells; B: SGC-7901 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL oxaliplatin (OXA); C: Untreated BGC-823 cells; D: BGC-823 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA; E: Untreated HGC-27 cells; F: HGC-27 cells treated with 5 × 109 vp/mL rAd-p53 plus 3.2 μg/mL OXA.

Table 3.

Bcl-2 expression in gastric cancer cells 48 h after treatment with rAd-p53, oxaliplatin or rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin

| Treatment | Gastric cancer cell line | ||||

| rAd-p53 (vp/mL) | OXA (μg/mL) | SGC-7901 | BGC-823 | HGC-27 | |

| OXA | 0 | 3.2 | 26.32 ± 1.21ea | 47.53 ± 1.13ea | 56.64 ± 1.33ea |

| rAd-p53 | 5 × 106 | 0 | 28.62 ± 1.07ca | 58.23 ± 1.04ca | 61.23 ± 1.07ca |

| 5 × 107 | 0 | 24.34 ± 1.05ca | 46.26 ± 1.31ca | 49.54 ± 1.14ca | |

| 5 × 108 | 0 | 18.62 ± 1.32ca | 40.81 ± 1.15ca | 47.34 ± 1.06ca | |

| 5 × 109 | 0 | 15.37 ± 1.51ca | 38.37 ± 1.08ca | 44.31 ± 1.03ca | |

| rAd-p53+ OXA | 5 × 106 | 3.2 | 21.76 ± 1.16eca | 35.63 ± 1.41eca | 38.18 ± 1.08eca |

| 5 × 107 | 3.2 | 18.34 ± 1.24eca | 32.37 ± 1.07eca | 35.71 ± 2.02eca | |

| 5 × 108 | 3.2 | 16.22 ± 1.02eca | 29.27 ± 1.13eca | 32.91 ± 1.24eca | |

| 5 × 109 | 3.2 | 13.14 ± 1.07eca | 26.74 ± 1.02eca | 29.84 ± 1.57eca | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 38.97 ± 1.06 | 73.71 ± 2.02 | 84.03 ± 1.02 |

P < 0.05 vs control;

P < 0.05, rAd-p53 vs rAd-p53 + oxaliplatin (OXA) with the same dose of rAd-p53;

P < 0.05, OXA vs rAd-p53 + OXA with the same dose of OXA.

Apoptotic ratio and expression of caspase-3 in gastric cancer cells treated with rAd-p53 or OXA alone or with rAd-p53 in combination with OXA

To confirm that the antitumor effects of rAd-p53 and OXA were associated with induction of apoptosis in gastric cancer cells, we examined the expression of caspase-3 and the apoptotic rate in the three different gastric cancer cell lines by flow cytometric analysis. We found that caspase-3 expression was higher in treated gastric cancer cells compared to untreated cells (P < 0.05). Moreover, the combined treatment with rAd-p53 and OXA presented synergistic effects in the upregulation of caspase-3 expression and induction of apoptosis (P < 0.05) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Caspase-3 expression in gastric cancer cells 48 h after treatment with rAd-p53, oxaliplatin or rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin

| Treatment | Gastric cancer cell line | ||||

| rAd-p53 (vp/mL) | OXA (μg/mL) | SGC-7901 | BGC-823 | HGC-27 | |

| OXA | 0 | 3.2 | 12.32 ± 0.8ea | 11.21 ± 1.05ea | 8.86 ± 1.01ea |

| rAd-p53 | 5 × 106 | 0 | 7.89 ± 1.13ca | 6.07 ± 0.97ca | 4.32 ± 1.03ca |

| 5 × 107 | 0 | 10.03 ± 1.03ca | 8.38 ± 1.04ca | 6.03 ± 0.99ca | |

| 5 × 108 | 0 | 12.34 ± 1.05ca | 10.52 ± 0.89ca | 8.31 ± 1.02ca | |

| 5 × 109 | 0 | 15.04 ± 1.03ca | 11.34 ± 0.55ca | 10.12 ± 1.01ca | |

| rAd-p53 + OXA | 5 × 106 | 3.2 | 22.05 ± 1.01eca | 15.67 ± 1.03eca | 13.48 ± 1.01eca |

| 5 × 107 | 3.2 | 25.13 ± 1.06eca | 18.83 ± 1.02eca | 15.32 ± 1.07eca | |

| 5 × 108 | 3.2 | 27.24 ± 1.73eca | 21.07 ± 1.01eca | 18.93 ± 1.06eca | |

| 5 × 109 | 3.2 | 35.67 ± 1.03eca | 26.16 ± 1.05eca | 22.34 ± 1.13eca | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 1.32 ± 1.02 | 1.29 ± 0.97 | 1.27 ± 0.68 |

P < 0.05 vs control;

P < 0.05, rAd-p53 vs rAd-p53 + oxaliplatin (OXA) with the same dose of rAd-p53;

P < 0.05, OXA vs rAd-p53 + OXA with the same dose of OXA.

Table 5.

Apoptotic rate in gastric cancer cells 48 h after treatment with rAd-p53, oxaliplatin or rAd-p53 plus oxaliplatin

| Treatment | Gastric cancer cell line | ||||

| rAd-p53 (vp/mL) | OXA (μg/mL) | SGC-7901 | BGC-823 | HGC-27 | |

| OXA | 0 | 3.2 | 33.52 ± 1.6ea | 23.28 ± 1.35ea | 18.72 ± 1.61ea |

| rAd-p53 | 5 × 106 | 0 | 7.89 ± 1.13ca | 6.51 ± 0.97ca | 4.07 ± 0.83ca |

| 5 × 107 | 0 | 12.47 ± 1.43ca | 8.78 ± 1.34ca | 6.43 ± 0.79ca | |

| 5 × 108 | 0 | 21.84 ± 1.05ca | 14.24 ± 0.89ca | 11.72 ± 1.12ca | |

| 5 × 109 | 0 | 36.73 ± 1.03ca | 28.64 ± 1.75ca | 21.82 ± 1.81ca | |

| rAd-p53 + OXA | 5 × 106 | 3.2 | 42.38 ± 1.51eca | 35.72 ± 1.13eca | 28.84 ± 1.21eca |

| 5 × 107 | 3.2 | 54.84 ± 1.26eca | 48.63 ± 1.62eca | 34.51 ± 1.47eca | |

| 5 × 108 | 3.2 | 58.41 ± 1.13eca | 51.71 ± 1.41eca | 38.5 ± 1.16eca | |

| 5 × 109 | 3.2 | 63.91 ± 1.23eca | 55.73 ± 1.35eca | 42.92 ± 1.33eca | |

| Control | 0 | 0 | 4.67 ± 1.32 | 1.74 ± 0.67 | 1.15 ± 0.58 |

P < 0.05 vs control;

P < 0.05, rAd-p53 vs rAd-p53 + oxaliplatin (OXA) with the same dose of rAd-p53;

P < 0.05, OXA vs rAd-p53 + OXA at the same dose of OXA.

DISCUSSION

As the most important tumor suppressor gene, p53 plays an important role in the induction of apoptosis. However, the mutation rate of p53 gene is approximately 50% in human cancers[4], leading to the loss of p53 function, including its induction of apoptosis. Available data suggest that p53 mutations are linked to the development of multiple malignant tumors, such as liver cancer, breast cancer, bladder carcinoma, gastric cancer, colon carcinoma, prostatic carcinoma, ovarian cancer, brain cancer, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, lymphocyte tumor, soft tissue sarcoma, and osteogenic sarcoma[5-20].

rAd-53, which is an adenovirus carrier containing the p53 tumor suppressor gene, is the first gene therapy drug. In this therapy, the adenovirus is used to deliver the p53 gene to target cells; restoration of p53 expression in the targeted cells results in antitumor effects. The mechanisms of p53 action include: (1) inhibition of cell cycle progression and induction of apoptosis in tumor cells through the modulation of the expression of apoptosis- and cell-cycle-related genes; (2) sensitization of tumor cells to radiotherapy and chemotherapy; and (3) stimulation of antitumor immunity through the bystander effect. Clinical application studies have demonstrated that rAd-p53 not only strengthens tumor cell sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy, but also reduces side effects of chemotherapy. For these reasons, a combination of p53 gene therapy and chemotherapy has been successfully applied to cure a variety of cancers, including lung adenocarcinoma, liver cancer and oophoroma[21,22].

In the present study, we treated three different gastric cancer cell lines with a combination of rAd-p53 and OXA and found that these agents had significant inhibitory effects on cancer cell growth that were dependent on treatment time and dose. In addition, we observed that more differentiated cells were more sensitive to rAd-p53 and OXA treatment. To investigate whether the antitumor effects of rAd-p53 and OXA are related to the induction of apoptosis in gastric cancer cells, we examined the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. Bcl-2 is the most important anti-apoptotic protein[23,24], whereas Bax is a pro-apoptotic protein[25]. Furthermore, it is well known that caspase-3 is critical in chemotherapy-induced apoptosis of cancer cells[26-30]. Therefore, we examined the expression of Bcl-2, Bax and caspase-3 in gastric cancer cells treated with rAd-p53. As expected, our results demonstrated that the expression Bax and caspase-3 was increased, whereas the expression of Bcl-2 was decreased in a dose-dependent manner. Consistent with these data, we found that the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells was increased.

In conclusion, in the present study, we demonstrated that rAd-p53 inhibited gastric cancer cell growth and sensitized these cells to the chemotherapeutic agent OXA. The underlying mechanisms of these effects involved the induction of apoptosis, which was achieved via downregulation of Bcl-2 and upregulation of Bax and caspase-3. Our results suggest that the combination of p53 gene therapy and chemotherapy represents a novel avenue for gastric cancer treatment.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer is the most common malignant tumor of the digestive system. Current major therapeutic methods for gastric cancer are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Despite recent improvements in these treatments, the > 5-year survival rate for gastric cancer patients is only up to 45%. Thus, it is urgent to develop new therapeutic approaches such as gene therapy for gastric cancer.

Research frontiers

p53 is known as the “genome guard” that plays important roles in various cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, DNA damage repair and apoptosis. p53 genetic mutation exists in > 50% human tumor tissues and it is the most common detected genetic mutation in cancer. Therefore, a gene therapy strategy has been developed to employ rAd-p53, a weakened adenovirus that carries the wild-type p53 gene, to make tumor cells sensitive to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clinical application of rAd-p53 has been carried out on lung cancer, breast cancer, oophoroma, liver cancer, and bladder carcinoma. However, few studies have investigated the therapeutic effects of rAd-p53 on gastric cancer.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In the present study, the authors demonstrated that rAd-p53 inhibited gastric cancer cell growth and sensitized them to chemotherapy by oxaliplatin (OXA). The underlying mechanisms were concerned with induction of apoptosis achieved via downregulation of bcl-2 and upregulation of Bax and caspase-3.

Applications

Given that p53 genetic mutation exists in > 60% of gastric cancers and is correlated with onset and prognosis of gastric cancer, and with chemosensitivity of gastric cancer, the authors’ findings that rAd-p53 had antitumor effects in gastric cancer is important for the application of rAd-p53 to clinical treatment of gastric cancer.

Terminology

Apoptosis is a process of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms. In contrast to necrosis, which is a form of traumatic cell death that results from acute cellular injury, apoptosis confers advantages during an organism’s life cycle by maintaining the balance of cell survival and death. However, an insufficient amount of apoptosis results in uncontrolled cell proliferation, such as cancer. Apoptosis is regulated by a balance between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic molecules.

Peer review

In this paper, the authors reported that rAd-p53 enhanced the sensitivity of gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy by promoting apoptosis. These results suggest that p53 gene therapy combined with chemotherapy is more effective for gastric cancer treatment than regular chemotherapy.

Footnotes

Supported by Xuzhou Science and Technology Development Fund, No. XM07C039

Peer reviewer: Dr. Paul M. Schneider, MD, Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Zurich, Raemistrasse 100, Zurich 8091, Switzerland

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Shiraishi K, Kato S, Han SY, Liu W, Otsuka K, Sakayori M, Ishida T, Takeda M, Kanamaru R, Ohuchi N, et al. Isolation of temperature-sensitive p53 mutations from a comprehensive missense mutation library. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:348–355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuball J, Wen SF, Leissner J, Atkins D, Meinhardt P, Quijano E, Engler H, Hutchins B, Maneval DC, Grace MJ, et al. Successful adenovirus-mediated wild-type p53 gene transfer in patients with bladder cancer by intravesical vector instillation. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:957–965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.4.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodsell DS. The molecular perspective: cadherin. Oncologist. 2002;7:467–468. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-5-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vikhanskaya F, D’Incalci M, Broggini M. p73 competes with p53 and attenuates its response in a human ovarian cancer cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:513–519. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.2.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KE, Lee HJ, Kim YH, Yu HJ, Yang HK, Kim WH, Lee KU, Choe KJ, Kim JP. Prognostic significance of p53, nm23, PCNA and c-erbB-2 in gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:173–179. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahrendt SA, Hu Y, Buta M, McDermott MP, Benoit N, Yang SC, Wu L, Sidransky D. P53 mutations and survival in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:961–970. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.13.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bressac B, Kew M, Wands J, Ozturk M. Selective G to T mutations of p53 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma from southern Africa. Nature. 1991;350:429–431. doi: 10.1038/350429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erber R, Conradt C, Homann N, Enders C, Finckh M, Dietz A, Weidauer H, Bosch FX. TP53 DNA contact mutations are selectively associated with allelic loss and have a strong clinical impact in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 1998;16:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan R, Wu MT, Miller D, Wain JC, Kelsey KT, Wiencke JK, Christiani DC. The p53 codon 72 polymorphism and lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1037–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueiredo BC, Sandrini R, Zambetti GP, Pereira RM, Cheng C, Liu W, Lacerda L, Pianovski MA, Michalkiewicz E, Jenkins J, et al. Penetrance of adrenocortical tumours associated with the germline TP53 R337H mutation. J Med Genet. 2006;43:91–96. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouquet C, Antoine M, Tisserand P, Favis R, Wislez M, Commo F, Rabbe N, Carette MF, Milleron B, Barany F, et al. Rapid and sensitive p53 alteration analysis in biopsies from lung cancer patients using a functional assay and a universal oligonucleotide array: a prospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3479–3489. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0994-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez KD, Noltner KA, Buzin CH, Gu D, Wen-Fong CY, Nguyen VQ, Han JH, Lowstuter K, Longmate J, Sommer SS, et al. Beyond Li Fraumeni Syndrome: clinical characteristics of families with p53 germline mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1250–1256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman JE, Hofseth LJ, Hussain SP, Harris CC. Nitric oxide and p53 in cancer-prone chronic inflammation and oxyradical overload disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:3–9. doi: 10.1002/em.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu IC, Metcalf RA, Sun T, Welsh JA, Wang NJ, Harris CC. Mutational hotspot in the p53 gene in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Nature. 1991;350:427–428. doi: 10.1038/350427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain SP, Harris CC. P53 mutation spectrum and load: The generation of hypotheses linking the exposure of endogenous or exogenous carcinogens to human cancer. Mutat Res. 1999;428:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain SP, Amstad P, Raja K, Ambs S, Nagashima M, Bennett WP, Shields PG, Ham AJ, Swenberg JA, Marrogi AJ, et al. Increased p53 mutation load in noncancerous colon tissue from ulcerative colitis: a cancer-prone chronic inflammatory disease. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3333–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain SP, Amstad P, Raja K, Sawyer M, Hofseth L, Shields PG, Hewer A, Phillips DH, Ryberg D, Haugen A, et al. Mutability of p53 hotspot codons to benzo(a)pyrene diol epoxide (BPDE) and the frequency of p53 mutations in nontumorous human lung. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6350–6355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain SP, Raja K, Amstad PA, Sawyer M, Trudel LJ, Wogan GN, Hofseth LJ, Shields PG, Billiar TR, Trautwein C, et al. Increased p53 mutation load in nontumorous human liver of wilson disease and hemochromatosis: oxyradical overload diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12770–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220416097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain SP, Schwank J, Staib F, Wang XW, Harris CC. TP53 mutations and hepatocellular carcinoma: insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of liver cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:2166–2176. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng Z. Current status of gendicine in China: recombinant human Ad-p53 agent for treatment of cancers. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1016–1027. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan YS, Liu Y, Sun L, Li X, He Q. Successful management of postoperative recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma with p53 gene therapy combining transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3803–3805. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i24.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cory S, Huang DC, Adams JM. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jong D, Prins FA, Mason DY, Reed JC, van Ommen GB, Kluin PM. Subcellular localization of the bcl-2 protein in malignant and normal lymphoid cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heon Seo K, Ko HM, Kim HA, Choi JH, Jun Park S, Kim KJ, Lee HK, Im SY. Platelet-activating factor induces up-regulation of antiapoptotic factors in a melanoma cell line through nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4681–4686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu XX, Mizutani Y, Kakehi Y, Yoshida O, Ogawa O. Enhancement of Fas-mediated apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma cells by adriamycin. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2912–2918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumi-Diaka J, Sanderson NA, Hall A. The mediating role of caspase-3 protease in the intracellular mechanism of genistein-induced apoptosis in human prostatic carcinoma cell lines, DU145 and LNCaP. Biol Cell. 2000;92:595–604. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(00)01109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang C, Wang Z, Ganther H, Lu J. Caspases as key executors of methyl selenium-induced apoptosis (anoikis) of DU-145 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3062–3070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner AD, Wedding U. Advances in the pharmacological treatment of gastro-oesophageal cancer. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:627–646. doi: 10.2165/11315740-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mueller S, Schittenhelm M, Honecker F, Malenke E, Lauber K, Wesselborg S, Hartmann JT, Bokemeyer C, Mayer F. Cell-cycle progression and response of germ cell tumors to cisplatin in vitro. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:471–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]