Abstract

Yersinia enterocolitica transports YscM1 and YscM2 via the type III pathway, a mechanism that is required for the establishment of bacterial infections. Prior to host cell contact, YscM1 and YscM2 exert posttranscriptional regulation to inhibit expression of effector yop genes, which encode virulence factors that travel the type III pathway into the cytoplasm of macrophages. Relief from repression has been predicted to occur via the type III secretion of YscM1 and YscM2 into the extracellular medium, resulting in the depletion of regulatory molecules from the bacterial cytoplasm. Using digitonin fractionation and fluorescence microscopy of FlAsH-labeled polypeptides in Yersinia-infected cells, we have localized YscM1 and YscM2 within the host cell cytoplasm. Type III injection of YscM1 and YscM2 required the SycH chaperone. Expression of C-terminal fusions of YscM1 and YscM2 to the neomycin phosphotransferase reporter revealed sequences required for regulatory activity and for secretion in the absence of SycH. Coexpression of SycH and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-YscM1 or GST-YscM2, hybrid GST variants that cannot be transported by the type III apparatus, also relieved repression of Yop synthesis. GST-SycH bound to YscM1 and YscM2 and activated effector yop expression without initiation of the bound regulatory molecules into the type III pathway. Further, regulation of yop expression by YscM1, YscM2, and SycH is shown to act independently of factors that regulate secretion, and gel filtration chromotography revealed populations of YscM1 and YscM2 that are not bound to SycH under conditions where Yop synthesis is repressed. Taken together, these results suggest that YscM1- and YscM2-mediated repression may be relieved through binding to the cytoplasmic chaperone SycH prior to their type III injection into host cells.

Several gram-negative bacterial pathogens employ a virulence strategy known as type III secretion to establish host infections (19). Three pathogenic Yersinia species, Yersinia pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica, share a common tropism for lymphatic tissues in their mammalian hosts (12). Yersiniae use the type III pathway for the secretion of virulence factors into the extracellular milieu (33, 35) and for the injection of effector Yops (Yersinia outer proteins) into the cytoplasm of host macrophages (48). Effector Yops control the fate of host cells, preventing phagocytosis and ultimately inducing cell death (12). There are 14 known type III secretion substrates in Y. enterocolitica, all of which are encoded within a 70-kb virulence plasmid (38). Six of these, YopE, YopH, YopM, YopO, YopP, and YopT, represent effector proteins (7, 20, 24, 31, 39, 40, 42, 48). The remaining substrates regulate Yop synthesis or secretion (LcrV, YopD, YopN, YopQ, YscM1, and YscM2) (2, 29, 41, 46, 52, 55), facilitate type III transport reactions (LcrV, YopB, and YopD) (23, 28), or assume other pathogenetic functions (YopB and YopR) (5, 35).

Upon entry into the host, Yersinia organisms respond to a temperature increase to 37°C and activate transcription of type III genes (21, 26). Synthesis and assembly of the type III apparatus is cued by a serum amino acid signal (34). A serum protein signal triggers the secretion of a subset of type III substrates (YopB, YopD, YopR, and LcrV) into the extracellular milieu (34). Finally, bacterial contact with macrophages results in a massive up-regulation of effector yop gene expression and subsequent injection of effector Yop substrates through type III needle complexes (43, 48), which extend into the cytoplasm of host cells (27, 34). Host cell contact provides a signal for type III transport by decreasing environmental calcium concentration from the millimolar range (serum concentration) to nanomolar concentrations in the host cell cytoplasm (34, 44). This phenomenon, termed the low-calcium response (Lcr), can be reconstituted in vitro, allowing for the study of type III secretion by Yersinia through chelation of calcium ions and recovery of Yop proteins from culture media (21, 38).

In Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis, effector yop expression as a result of host cell contact is controlled by LcrQ (43, 46). The lcrQ gene encodes a 12-kDa secretion substrate that blocks the expression of effector yop genes in the bacterial cytoplasm (46). Depletion of LcrQ from the cytoplasm via type III secretion or lowering of its intracellular concentration has been predicted to function as a switch that controls the amplitude of yop expression (43, 57). This model resembles the transcriptional control of flagellar biosynthesis, a type III pathway that is regulated by the sigma factor 28 (FliA) and its cognate anti-sigma factor, encoded by flgM. As Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium completes the flagellar hook and basal body, FlgM is depleted from the cytoplasm via secretion, thereby allowing FliA-mediated transcription of flagellin genes (30). While these models share similarities, LcrQ does not appear to function as an anti-sigma factor and it requires at least two additional factors to regulate yop expression (see below).

A deletion in lcrQ fails to block the expression of effector yop genes but does not lead to premature secretion of this subset of proteins, suggesting that LcrQ acts only at the level of expression but does not control secretion reactions (43). Further, overexpression of lcrQ abolishes effector yop synthesis under conditions that promote type III secretion (low calcium) (55, 57). Y. enterocolitica carries two homologs of lcrQ on the virulence plasmid, yscM1 and yscM2 (52). Knockout mutations in yscM1 and yscM2, but not single mutations, display the lcrQ phenotype (9, 52). Overexpression of each gene alone (yscM1 or yscM2) is sufficient to block the expression of yop genes in a wild-type bacterial cell, but yscM1 and yscM2 alone are not fully sufficient for this repressor activity (9). YopD in Y. pestis, a type III secretion substrate required for the injection of effector Yops, and LcrH (SycD) in Y. pseudotuberculosis, a chaperone required for the secretion of YopD, are both essential for LcrQ activity (17, 46, 55). In Y. enterocolitica, both yopD and lcrH were found to be required for yscM1- and yscM2-mediated regulation, and all four genes act synergistically at the same regulatory step to block the expression of yop genes (2, 9).

Recent studies suggested that YopD, LcrH, YscM1, and YscM2 block expression of yop genes by a posttranscriptional mechanism (2, 9). yopQ is the most tightly regulated type III secretion substrate in Y. enterocolitica and has been used as a model for the study of regulation (2). Mutations in yopD, lcrH, or yscM1/yscM2 result in synthesis of YopQ in the presence of calcium, an environmental condition where yopQ is normally not expressed (2). Although yopQ is not translated in strains that are grown in the presence of calcium, transcript levels remain similar in cells irrespective of calcium concentration, suggesting a translational regulation of yopQ expression (9). Overexpression of yscM1 or yscM2 does not affect the levels of transcript of yopQ but eliminates any YopQ immunoreactive signal (9). This translational block has been mapped to the 5′ untranslated region of yopQ mRNA, where a conserved sequence 5′-AUAAA-3′ common to the 5′ untranslated regions of several effector yop genes was found to be necessary for yscM1/yscM2 mediated regulation (9). In vitro, purified YopD-LcrH complex has also been shown to have an affinity for a nucleotide −45 to + 45 yopQ mRNA, suggesting that YopD, LcrH, YscM1, and YscM2 prevent translation of yop mRNAs (2).

The type III injection of effector Yops requires binding factors in the bacterial cytoplasm, named Syc (specific Yop chaperones) (53). Syc proteins are small acidic (10 to 20 kDa) polypeptides that bind cognate Yop substrates in the bacterial cytoplasm (54). Although the Syc-Yop protein interaction is required for the injection of Yop substrates during infection, it is dispensable for the secretion of Yop proteins in vitro (10). Yop proteins destined for transport into host cells harbor two signals; one signal is located in 5′ mRNA coding sequence (N-terminal signal) (3, 37, 45), and the second signal is located downstream and encodes the binding site for the cognate Syc chaperone (11, 50). SycH is a chaperone for YopH, a tyrosine phosphatase that targets focal adhesions in macrophages (6, 14, 56). YopH harbors multiple domains, including a C-terminal enzymatic domain and an N-terminal secretion signal domain (50). YscM1 and YscM2 share a high degree of sequence identity with the N-terminal domain of YopH, especially in the SycH binding domain between residues 20 and 69 (56). This similarity is functional, as both YscM1 and YscM2 bind SycH in vitro (8). Previous work suggested that YopH, LcrQ, and YscM1 are injected into host cells; however, the subcellular localization of YscM2 during infection has been unresolved (8, 42).

We show here that SycH is required for the injection of YopH, YscM1, and YscM2 into the cytoplasm of HeLa cells. Two independent assays were used to measure YscM1 and YscM2 injection, digitonin fractionation and microscopic detection of FlAsH-labeled polypeptides (1). Reporter fusions of YscM1 and YscM2 to neomycin phosphotransferase revealed sequences required for regulatory activity and for secretion in the absence of SycH. The binding of SycH to YscM1 and YscM2, both in the presence and in the absence of functional type III pathways, induced the expression of effector yop genes, and this level of regulation is shown to be independent from factors that regulate secretion. We predict that a population of YscM1 and YscM2 blocks expression of yop genes when they are not bound to SycH, and it appears that SycH binding, but not YscM1 and YsM2 secretion, may induce effector yop expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. Y. enterocolitica strain EC8 (ΔsycH) was constructed by allelic exchange utilizing the suicide plasmid pECΔsycH, which carries a deletion mutant allele of sycH. Strain EC8 was generated through mating of Escherichia coli S17-1(pECΔsycH) with Y. enterocolitica EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)]. Strain EC10 (ΔyopH) was constructed by allelic exchange utilizing the suicide plasmid pECΔyopH, which carries a deletion mutant allele of yopH, in a mating of E. coli S17-1(pECΔyopH) with Y. enterocolitica W22703(pYVe227) by using a previously described technology (10).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica strains | ||

| W22703 | O:9 serotype, pYVe227, Nalr, wild-type isolate | 13 |

| CT133 | ΔlcrH, Nalr | 2 |

| EC1 | ΔpYVe227, Nalr | This study |

| EC2 | Δ(yscM1, yscM2), Nalr | 8 |

| EC8 | Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH), Nalr | This study |

| EC10 | ΔyopH, Nalr | This study |

| EC13 | ΔsycH, Nalr | 8 |

| KUM1 | ΔyscV, Nalr | 10 |

| VTL1 | ΔyopN, Nalr | 33 |

| VTL2 | ΔyopD, Nalr | 35 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (ϕ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi1 relA1 | 25 |

| S17-1 | thi pro recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 str (λpir+), hsdR mutant, hsdM mutant | 15 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDA259 | tac promoter fused to gst, Cmr | 4 |

| pEC124 | tac promoter fused to yscM1-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC125 | tac promoter fused to yscM11-80-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC126 | tac promoter fused to yscM11-15-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC130 | tac promoter fused to yscM2-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC131 | tac promoter fused to yscM21-80-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC132 | tac promoter fused to yscM21-15-npt, Cmr | This study |

| pEC150 | tac promoter fused to sycH, Tetr | This study |

| pEC159 | tac promoter fused to yscM1-Cys4, Cmr | This study |

| pEC160 | tac promoter fused to yscM2-Cys4, Cmr | This study |

| pEC346 | tac promoter fused to gst-yscM1, Cmr | 8 |

| pEC349 | tac promoter fused to gst-yscM2, Cmr | 8 |

| pEC441 | tac promoter fused to sycH, Cmr | 8 |

| pEC442 | tac promoter fused to gst-sycH, Cmr | This study |

| pECΔsycH | pLC28 derivative, sycH deletion construct | 8 |

| pECΔyopH | pLC28 derivative, yopH deletion construct | This study |

Plasmid pDA41 (pHSG576, low copy) (3) was cut with NdeI and KpnI, and the vector fragment was ligated to yscM1 open reading frame (ORF) fragments containing 5′ NdeI and 3′ KpnI sites synthesized with the primers YscM1.1 (5′-AACATATGAAAATCAATACTCTTCAATCG-3′) and YscM1.2 (5′-AAGGTACCGCCGTCAGCCGCCGTATC-3′), thereby generating pEC124, or with primers YscM1.1 and YscM1.3 (5′-AAGGTACCCTTGCCCTGCTTTAGTTCCA-3′), generating pEC125. Ligation of NdeI- and KpnI-digested pDA41 with yscM2 ORF fragments synthesized with the primers YscM2.8 (5′-AACATATGGAAATAAACGATCTTCAATC-3′) and YscM2.9 (5′-AAGGTACCAGTTGTGATATTAAAGCTTTTGC-3′) generated pEC130, and synthesis with YscM2.8 and YscM2.10 (5′-AAGGTACCTTTTTTTCCTTGACTTAACTCAA-3′) generated pEC131. A similar approach was used to generate pEC126 and pEC132 by ligating pDA41 vector cut with NdeI and KpnI to a set of annealed oligonucleotides, M1/1-15+ (5′-TATGAAAATCAATACTCTTCAATCGTTAATAAATCAACAAATTACCGGTAC-3′) and M1/1-15− (CGGTAATTTGTTGATTTATTAACGATTGAAGAGTATTGATTTTCA-3′) for pEC126 and M2/1-15+ (5′-TATGGAAATAAACGATCTTCAATCATTAATAAGCATGCAAATTGCAGGTAC-3′) and M2/1-15− (5′-CTGCAATTTGCATGCTTATTAATGATTGAAGATCGTTTATTTCCA-3′) for pEC132, which contain codons 1 to 15 of yscM1 or yscM2 between NdeI and KpnI restriction sites. pEC150 was constructed through ligation of pEC260 (pMPM, low copy) (9) vector backbone to a sycH ORF fragment containing 5′ NdeI and 3′ BamHI sites generated with the primers SycH6 (5′-AACATATGCGCACTTACAGTTCATTAC-3′) and SycH7 (5′-AAGGATCCTTAAACCAGTAAATGAGATGATG-3′). pEC442 was constructed through ligation of pEC347 (pMPM, low copy) (9) vector cut with KpnI and BamHI to a sycH ORF fragment containing 5′ KpnI and 3′ BamHI sites generated with the primers SycH5 (5′-AAGGTACCCGCACTTACAGTTCATTAC-3′) and SycH7. pEC159 and pEC160 were generated through ligation of pEC345 (8) vector digested with NdeI and BamHI with 5′ NdeI/3′ BamHI yscM1 or full-length yscM2 (minus stop codon) in-frame fusions to a 17-codon Cys4-containing sequence generated by PCR with the primers YscM1.1 and YscM13′FlAsH (5′-AAGGATCCTCAAGCACGAGCGCAACATTCTCTGCAACAAGCTTCACGTGCGGCAGCTTCGCCGTCAGCCGCCGTATC-3′) for pEC159 and YscM2.8 and YscM23′FlAsH (5′-AAGGATCCTCAAGCACTAGCGCAACATTCTCTGCAACAAGCTTCACGTGCGGCAGCTTCAGTTGTGATATTAAAGCTTTTGC-3′) for pEC160. pECΔyopH was constructed through a three-way ligation of pLC28 (11) liberated with XhoI and XbaI with a 5′ XhoI/NcoI fragment containing ∼1,000 bases upstream relative to the yopH translational start plus the first 10 codons generated with the primers YopH1 (5′-AACTCGAGGGGCAGGCCGGTCTCAC-3′) and YopH2 (5′-AACCATGGCGATGAAGATCGCTTAATGATA-3′) and a 5′ NcoI/XbaI fragment containing the last 10 codons and ∼1,200 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon generated with the primers YopH3 (5′-AACCATGGACAAGGGCGACCATTATTAAAT-3′) and YopH4 (5′-AATCTAGACACTCGGATCAAGGCAGTC-3′). pYVe227 was used as a template for all PCRs with a standard protocol. Ligations were transformed into E. coli DH5α and screened by restriction analysis. Plasmid constructs were sequenced by fluorescent-labeled dideoxy chain termination PCRs (University of Chicago CRC DNA Sequencing facility). All DNA cloning manipulations were performed with pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) in E. coli DH5α. Plasmid constructs were electroporated into Yersinia strains, and transformants were selected on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) or tetracycline (5 μg ml−1) and incubated at 26°C.

Yersinia secretion.

Yersinia strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) or 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) to induce the type III pathway, and protein secretion was measured by immunoblotting of culture medium and bacterial extracts as previously described (9).

Affinity purifications.

Yersinia strains were grown to stationary phase overnight in TSB supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1) and diluted 1:50 in 1 liter of fresh TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) and antibiotics in Erlenmeyer flasks. Cultures were incubated on an orbital shaker (150 rpm) for 2 h at 26°C and induced at 37°C for 3 h. Expression constructs were induced at the time of temperature shift with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cultures were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Bacterial pellets were suspended in 20 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 6.8], 150 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Casamino Acids) and lysed with a French pressure cell (18,000 lb/in2). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 32,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Twenty milliliters of clarified lysates was loaded onto glutathione-Sepharose columns. Columns were washed with 20 ml of lysis buffer, 20 ml of lysis buffer with 10% glycerol, and 20 ml of lysis buffer. Columns were eluted with 4 ml of 20 mM glutathione in lysis buffer. Eluates were suspended in sample buffer and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-15% PAGE) and immunoblotting.

Gel filtration chromatography.

Yersinia strains were grown to stationary phase overnight in TSB and diluted 1:50 in 2 liters of fresh TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) or 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) in Erlenmeyer flasks. Cultures were incubated on an orbital shaker (150 rpm) for 2 h at 26°C and induced at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Bacterial pellets were suspended in 20 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and lysed with a French pressure cell (18,000 lb/in2). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 32,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Clarified lysates (0.5 ml) were separated on a Superdex 75 gel filtration column via fast protein liquid chromatography (Amersham Pharmacia). One-milliliter fractions were collected, mixed with sample buffer, and examined by immunoblotting.

Digitonin fractionation.

HeLa (CCL-2) cells were grown in 15 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum, and 2 mM glutamine to 80 to 90% confluence in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks at 37°C-5% CO2. Two hours prior to infection, overnight Yersinia cultures were diluted 1:20 in 20 ml of TSB with appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 26°C on an orbital shaker. One hour prior to infection, HeLa cells were washed twice with 5 ml of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 10 ml of DMEM-1 mM IPTG (where appropriate) was added to each flask, and the mixtures were incubated. Expression constructs in Yersinia strains were induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG 15 min prior to infection. Aliquots of HeLa cells were counted, and each flask was inoculated with Yersinia strains at a multiplicity of infection of 10. Flasks were incubated for 3 h at 37°C-5% CO2. Culture medium was decanted and centrifuged at 32,000 × g for 15 min to separate soluble proteins from nonadherent bacteria. Ten milliliters of 1% digitonin in 1× PBS was added to the HeLa cell monolayer containing adherent bacteria, and flasks were shaken at 26°C for 20 min. HeLa cells were scraped off, and samples were centrifuged at 32,500 × g for 15 min. Seven-milliliter aliquots were withdrawn and precipitated with methanol-chloroform, and the remaining supernatants were discarded. The sediments were suspended in 10 ml of 1% SDS in 1× PBS, and 7-ml aliquots were precipitated with methanol-chloroform. Protein precipitates were solubilized in sample buffer and examined by immunoblotting.

Phalloidin labeling of eukaryotic cells.

HeLa cells (2.5 ×105) were seeded onto 18-mm-diameter glass coverslips in 12-well tissue culture plates containing 1 ml of DMEM, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 2 mM glutamine per well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C-5% CO2. Two hours prior to infection, overnight Yersinia cultures were diluted 1:20 in TSB with the appropriate antibiotics and incubated at 26°C on a roller wheel. One hour prior to infection, HeLa cells were washed with 1 ml of PBS, 1 ml of DMEM-1 mM IPTG (where appropriate) was added to each well, and plates were returned to the incubator. Expression constructs in Yersinia strains were induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG 15 min prior to infection. Yersinia cells (5 × 106) were inoculated (multiplicity of infection, 10:1) and allowed to infect for 3 h at 37°C-5% CO2. The medium was removed, and each well was washed with 1 ml of PBS. Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min on a shaker at room temperature. Fixed samples were quenched with the addition of 1 ml of 0.1 M glycine for 10 min. Samples were permeabilized with 1 ml of 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min, blocked with 1 ml of 5% skim milk and 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS for 15 min, labeled with 1 ml of 165 nM Texas red-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes) in 5% skim milk and 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS for 20 min, covered (dark), and shaken at room temperature. The labeling solution was removed, and each well was washed four times with 1 ml of PBS, aspirated, and dried for 1 h. Coverslips were affixed to glass slides and visualized with an Olympus AX RL module microscope. Texas red-phalloidin visualization was achieved through excitation (591 nm) and emission (608 nm) with a U-MNG cube. Photos were captured with a Hamamatsu Ocra digital camera.

FlAsH labeling of eukaryotic cells.

HeLa cells were seeded onto 18-mm-diameter glass coverslips, grown, and infected with Yersinia as described above. Cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min on a shaker at room temperature. Samples were quenched with the addition of 1 ml of 0.1 M glycine for 10 min. Wells were washed with 1 ml of PBS. Samples were labeled with 1 ml of 1 μM FlAsH-EDT2 (Panvera) in HBS (50 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.5], 140 mM NaCl), 10 mM glucose, 1 mM Na pyruvate, and 20 μM ethanedithiol (EDT) for 1 h, covered (dark), and shaken at room temperature. The labeling solution was removed, and samples were washed with 1 ml of HBS containing 10 mM glucose, 1 mM Na pyruvate, 1 mM Patent Blue V, 20 μM EDT, and 20 μM Disperse Blue 3 for 30 min, rinsed with 1 ml of buffer minus blue dyes, aspirated, and dried for 1 h. Coverslips were affixed to glass slides and visualized with an Olympus AX RL module microscope. FlAsH visualization was achieved through excitation (500 nm) and emission (535 nm) with a U-MNIB cube. Photos were captured with a Hamamatsu Ocra digital camera.

Amino acid sequence alignment.

The sequences of YscM1 (NP_052423), YscM2 (NP_052432), and YopH (NP_052424) were obtained from GenBank (accession no. AF102990). Studies with yscM2 in this work utilize a second translational start site that is four codons downstream of the predicted translational start site of the yscM2 sequence in GenBank. We predict this allele to be the actual start site for yscM2, as the polypeptide retains repressor function and the sequence carries type III secretion signal information. Sequence alignment was performed by using Multalin multiple-sequence alignment.

RESULTS

Yersinia targets YscM1 and YscM2 in the cytoplasm of HeLa cells.

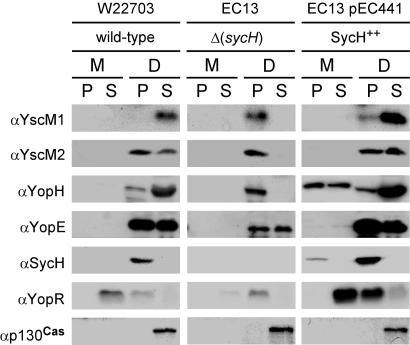

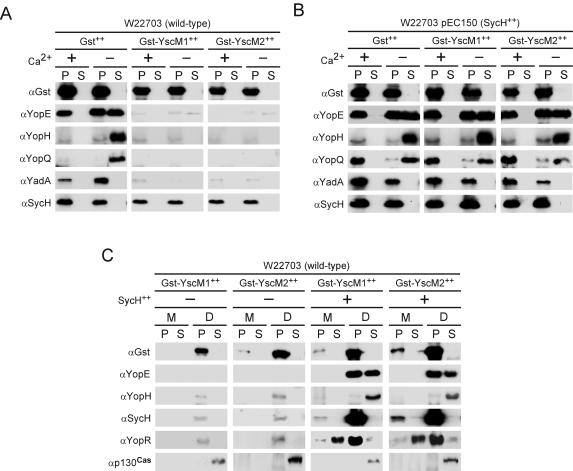

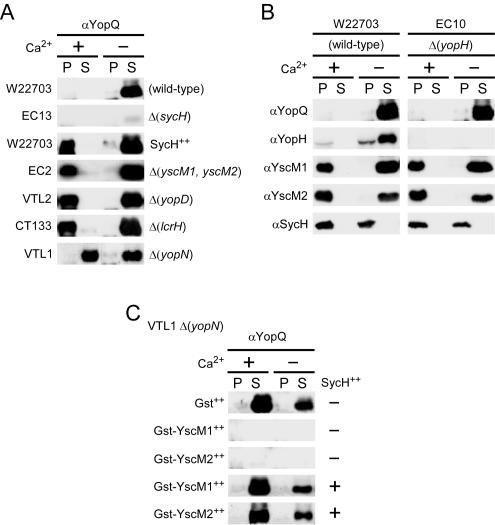

Previous work left unresolved the fate of YscM2 during Yersinia infection of tissue culture cells (8). To address this question, we raised a new polyclonal rabbit antiserum against purified YscM2 (data not shown). To determine the localization of YscM2, wild-type Y. enterocolitica was allowed to infect confluent HeLa cell monolayers for 3 h at 37°C. Tissue culture medium was decanted and centrifuged to separate nonadherent bacteria in the sediment from the extracellular medium in the supernatant. Adherent bacteria and HeLa cells were extracted with 1% digitonin, a detergent that selectively permeabilizes cholesterol-containing membranes without disturbing the integrity of the bacterial envelope (33). Extract was harvested and centrifuged to separate the sediment containing bacteria and cellular debris from host cell cytoplasm in the supernatant. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with chloroform-methanol and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. As expected, digitonin extraction released host p130Cas and Yersinia effectors YopE and YopH from the cytoplasm of HeLa cells (Fig. 1). Yersinia SycH remained associated with the bacteria and sedimented into the pellet fraction after digitonin extraction, and YopR was found secreted into the culture medium (Fig. 1). YscM1 and YscM2 were found in the supernatant of digitonin-extracted HeLa cells, suggesting that both regulatory proteins are injected into the cytoplasm of host cells (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Yersinia strains inject YscM1, YscM2, and YopH into HeLa cells in a sycH-dependent manner. Y. enterocolitica strains W22703 (wild type), EC13 (ΔsycH), and EC13(pEC441) (SycH++) were inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers for 3 h at 37°C. The tissue culture medium (M) was decanted and centrifuged to separate proteins secreted to the extracellular medium (supernatant [S]) from those present within nonadherent bacteria (pellet [P]). HeLa cells and adherent yersiniae were extracted with digitonin (D), a detergent that selectively permeabilizes cholesterol-containing membranes without solubilizing the bacterial envelope. Extracts were centrifuged to separate proteins solubilized from the HeLa cytoplasm (S) from those that sediment with the bacteria (P). Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with methanol-chloroform and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against YscM1, YscM2, YopH, YopE, SycH, YopR, and p130Cas.

SycH is required for type III targeting of YscM1, YscM2, and YopH.

To study the role of sycH in type III transport of YscM1 and YscM2, Y. enterocolitica EC13 (ΔsycH) was used for infection of HeLa cells (Fig. 1). In the absence of their cognate chaperone, YscM1, YscM2, and YopH were not detected in the supernatant of digitonin-extracted cells, suggesting that sycH is indeed required for the injection of all three substrates (Fig. 1). Failure of the mutant strain to inject YscM1, YscM2, or YopH was accompanied by a decrease in synthesis of YopE and YopR as well as by the loss of YopR secretion (Fig. 1). This defect in regulation was fully complemented in trans by expression of plasmid-borne wild-type sycH (pEC441) (Fig. 1). Further, overexpression of sycH resulted in injection of YopH and in the secretion of this protein into the extracellular medium. In contrast, the fidelity of YopR secretion or YscM1, YscM2, and YopE injection were not affected. Thus, in the absence of SycH, YscM1- and YscM2-mediated repression of Yop synthesis is not fully relieved during Yersinia infection of tissue culture cells.

FlAsH labeling of type III-injected YscM1 and YscM2.

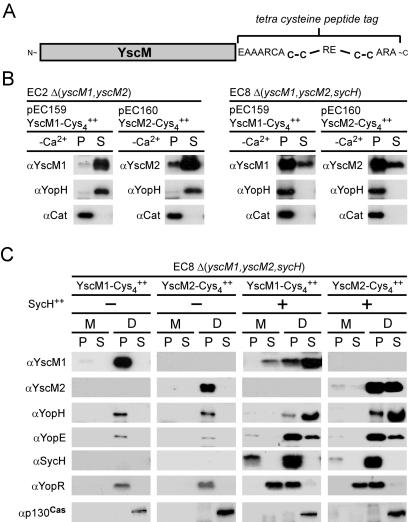

We sought to develop an assay that permits localization of Yersinia proteins in living cells. Our experimental strategy involved fusion of a 16-amino-acid tetracysteine peptide tag (22) to the C-terminal end of secretion substrates (YscM1 and YscM2 in this study) in an effort to measure type III injection via FlAsH labeling (see below) (Fig. 2A). Because overexpression of yscM1 or yscM2 in wild-type yersiniae leads to repression of the yop virulon (52), plasmids pEC159 (yscM1-cys4) and pEC160 (yscM2-cys4) were transformed into Y. enterocolitica EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)]. Bacteria were cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) at 37°C to induce type III secretion. Cultures were centrifuged, and the extracellular medium was separated from the bacterial sediment. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 were synthesized in strain EC2 and secreted into the culture medium (Fig. 2B). The synthesis and secretion of YopH was not affected by the expression of yscM1-cys4 or yscM2-cys4 (Fig. 2B). Plasmids pEC159 and pEC160 were also transformed into Y. enterocolitica EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)] and examined for secretion of YscM1-Cys4, YscM2-Cys4, and YopH under low-calcium conditions (Fig. 2B). YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 were found in the culture medium, albeit at reduced levels, suggesting that sycH is not absolutely required for YscM1 or YscM2 secretion in vitro. In contrast, YopH was synthesized but not secreted by strain EC8 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Type III transport of tetracysteine peptide-tagged YscM1 and YscM2. (A) Illustration of C-terminal fusions of YscM1 (pEC159) or YscM2 (pEC160) to the 16-amino-acid Cys4 peptide tag. (B) Y. enterocolitica strains EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)] and EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)] harboring plasmid pEC159 (carrying yscM1-Cys4) or pEC160 (carrying yscM2-Cys4) were cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged to separate the bacterial pellet (P) from the culture supernatant (S). Proteins in both fractions were precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against YscM1, YscM2, YopH, and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cat). (C) Y. enterocolitica strain EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)] harboring plasmid pEC159 or pEC160 without (−) or with (+) pEC150 (carrying sycH) were inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers for 3 h at 37°C and processed with digitonin fractionation as described for Fig. 1. Protein from each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera raised against YscM1, YscM2, YopH, YopE, SycH, YopR, and p130Cas.

Y. enterocolitica strain EC8 harboring plasmids pEC159 or pEC160 was used for infection of HeLa cells (Fig. 2C). In the absence of sycH, expression of yscM1-cys4 or yscM2-cys4 led to severe repression of yop synthesis and both YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 failed to be targeted into the cytoplasm of HeLa cells (Fig. 2C). However, when strain EC8 was transformed with a second plasmid, pEC150 carrying sycH, YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 were recovered in the digitonin-soluble fraction, and the expression, secretion, and targeting of type III substrates was restored (Fig. 2C). Thus, YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 are suitable substrates for FlAsH labeling studies when used in yersiniae expressing the SycH chaperone.

FlAsH, a bis-arsenical fluorophore whose emission is quenched by the chelator EDT, can bind to the C-terminal tetracysteine peptide tag appended to YscM1 and YscM2, thereby displacing the quencher and emitting fluorescent light at 535 nm (1, 18). Y. enterocolitica EC8 expressing yscM1-cys4 or yscM2-cys4 (in the presence or absence of coexpressed sycH) were used to infect HeLa cells for 3 h, and cells were labeled with FlAsH-EDT2 for 1 h. After washing, slides were examined by light and fluorescence microscopy. In the absence of sycH, strains expressing yscM1-cys4 or yscM2-cys4 did not result in FlAsH labeling of HeLa cells. However, in the presence of sycH, yscM1-cys4 and yscM2-cys4 expression led to FlAsH fluorescence of HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). As expected, coexpression of yscM1-cys4 or yscM2-cys4 with sycH in the type III secretion mutant KUM1 (ΔyscV) did not result in FlAsH labeling of HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). Together, these results corroborate the observation that YscM1 and YscM2 are injected into tissue culture cells and provide evidence that FlAsH labeling can be used as an assay for the detection of type III transport substrates in host cells.

FIG. 3.

FlAsH labeling of YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 during Yersinia infection of HeLa cells. (A) Illustration of C-terminal fusions of YscM1 (pEC159) or YscM2 (pEC160) to the 16-amino-acid Cys4 peptide tag and their interaction with the FlAsH label. (B) Y. enterocolitica strains EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)] and KUM1 (ΔyscV) harboring plasmid pEC159 or pEC160 without (−) or with (+) pEC150 (carrying sycH) were inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers on glass coverslips for 3 h at 37°C. Culture medium was removed, and cells were washed and fixed with formaldehyde. Samples were labeled with 1 μM FlAsH-EDT2 for 1 h. Label was removed, and samples were washed, aspirated, and dried. Images were captured on an Olympus microscope with a Hamamatsu Ocra digital camera. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were captured at a magnification of ×600, and fluorescence (FlAsH) was captured at 535-nm emission. Bar, 20 μm.

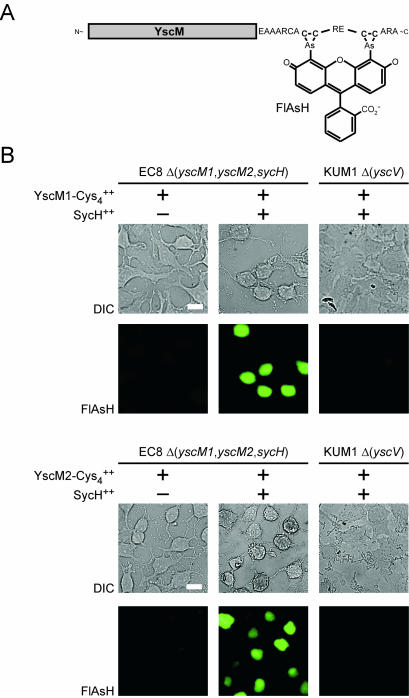

YscM1 and YscM2 sequences required for regulation and secretion.

YscM1 and YscM2 share a large degree of sequence identity with the N-terminal domain of YopH, spanning almost the entire length of these polypeptides (Fig. 4A). In contrast to YscM1 and YscM2, YopH does not seem to display regulatory properties. The SycH binding domain of YopH has been mapped to residues 20 to 69 (56), and recent structural information revealed surface exposed residues in YopH that are conserved in YscM1 and YscM2 (16, 49) (Fig. 4A). As the SycH binding domain is important for the initiation of YopH, YscM1, and YscM2 transport into eukaryotic cells, we wondered whether one could distinguish YscM1 and YscM2 domains that are required for secretion from those that are needed for regulation (Fig. 4B). By generating translational gene fusions, the cytoplasmic reporter protein neomycin phosphotransferase (Npt) was tethered to the C-terminal end of YscM1 and YscM2 (3). Recombinant plasmids carrying gene fusions were transformed into Y. enterocolitica strains EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)] and EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)], and expression of hybrid proteins in the presence of calcium was examined by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B). The type III pathway was induced by bacterial growth in TSB without calcium, and type III secretion was measured in fractionated cultures. Fusion of full-length yscM1 or yscM2 to npt (pEC124/pEC130) resulted in hybrid proteins with regulatory properties similar to those of wild-type YscM1 and YscM2, as yscM1-npt and yscM2-npt prevented the expression of yopH and failed to promote efficient type III secretion of YscM1-Npt and YscM2-Npt (Fig. 4C). Truncation of 3′ yscM coding sequences removed C-terminal YscM residues, thereby generating the hybrids YscM11-80-Npt and YscM21-80-Npt. Both hybrids were secreted in the absence of calcium and did not exert a regulatory effect on the synthesis and secretion of YopH. These data indicate that amino acid residues 81 to 115 and 81 to 116 are required for the regulatory function of YscM1 and YscM2, respectively. Furthermore, type III secretion of YscM1 and YscM2 fusions occurred both in the absence and in the presence of a functional sycH gene, consistent with previous reports that minimal secretion signals of Yop proteins promote substrate recognition under low-calcium conditions (3, 51). Consistent with this hypothesis is the observation that yersiniae secreted YscM11-15-Npt and YscM21-15-Npt in both the presence and the absence of SycH. As expected, YscM11-15-Npt and YscM21-15-Npt did not exert a regulatory activity on the synthesis or secretion of YopH.

FIG. 4.

Identification of YscM1 and YscM2 sequences required for regulation and secretion. (A) Amino acid sequence alignment of YscM1, YscM2, and the N-terminal domain of YopH. Positions that are conserved among all three polypeptides are shaded. The grey bar indicates the predicted SycH binding domain of YopH, with stars denoting predicted conserved surface-exposed residues. Numbers at the top of the alignment designate amino acid positions relative to YscM1, and numbers on the bottom designate positions relative to YopH. (B, left panel) Illustration of C-terminal truncations of YscM1 or YscM2 fused to neomycin phosphotransferase (Npt) with the predicted SycH binding domain located in the shaded box in YscM and YopH. (Right panel) Y. enterocolitica strain EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)] harboring the plasmids pEC124 (carrying yscM1-npt), pEC125 (carrying yscM11-80-npt), pEC126 (carrying yscM11-15-npt), pEC130 (carrying yscM2-npt), pEC131 (carrying yscM21-80-npt), or pEC132 (carrying yscM21-15-npt) were cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged to separate the bacterial pellet (P) from the culture supernatant (S). Proteins in both fractions were precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against Npt. (C) Same as for panel B, except strains were cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+). The signal for YopH is included as a control for YscM function, and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (Cat) is included as a fractionation control. (D) Same as for panel C, except all expression vectors were introduced to the strain EC8 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2, sycH)].

SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2 activates effector Yop synthesis.

Appending glutathione S-transferase (GST) to the N termini of YscM1 and YscM2 generates GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 fusions that repress the synthesis of yop genes in Y. enterocolitica, similar to wild-type YscM1 and YscM2 (8, 9). The N-terminal GST fusions block the type III secretion of hybrid proteins and result in a failure to activate yop expression (8). Y. enterocolitica W22703 expressing gst (pDA259), gst-yscM1 (pEC346), or gst-yscM2 (pEC349) was cultured in the presence or absence of calcium, and YopE, YopH, YopQ, SycH, and the surface adhesin YadA were examined for synthesis and secretion (Fig. 5A). Compared to a control strain expressing gst alone, gst-yscM1 and gst-yscM2 inhibited the synthesis of YopE, YopH, YopQ, and YadA but did not affect the synthesis of SycH (Fig. 5A). Coexpression of sycH in strains expressing gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 led to a complete restoration of the synthesis of YopE, YopH, YopQ, and YadA (Fig. 5B). YopQ, a factor that normally is not expressed in the presence of calcium, is synthesized under these conditions (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that SycH binding to GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 is sufficient for the activation of yop expression and that secretion of YscM1 and YscM2 may not be absolutely required for this regulatory event.

FIG. 5.

SycH binding relieves repression of Yop synthesis caused by GST-YscM1 or GST-YscM2 expression. (A) Y. enterocolitica W22703 (wild type) harboring the plasmid pDA259 (carrying gst), pEC346 (carrying gst-yscM1), or pEC349 (carrying gst-yscM2) was cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) or 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged to separate the bacterial pellet (P) from the culture supernatant (S). Proteins in both fractions were precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against GST, YopE, YopH, YopQ, YadA, and SycH. (B) Same as for panel A, except that each strain also harbors pEC150 (carrying sycH). (C) Y. enterocolitica W22703 harboring plasmid pDA259, pEC346, or pEC349 without (−) or with (+) pEC150 was inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers for 3 h at 37°C and processed with digitonin fractionation as described for Fig. 1. Protein from each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera raised against GST, YopE, YopH, SycH, YopR, and p130Cas.

When Y. enterocolitica W22703 expressing gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 was used to infect tissue culture cells, digitonin fractionation and immunoblotting revealed a strong decrease in the synthesis of YopE, YopH, YopR, and SycH (Fig. 5C). GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 remained associated with the bacterium and sedimented after digitonin extraction. Secretion of YopR into the extracellular medium and type III injection of YopE and YopH could not be detected (Fig. 5C). Defects in Yop synthesis and protein localization were restored by coexpression of sycH with gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 in Y. enterocolitica W22703 (Fig. 5C). As expected, GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 failed to be transported into the host cell cytoplasm; however, secretion of YopR and injection of YopE and YopH were restored to wild-type levels (Fig. 5C). It therefore appears that the binding of SycH to YscM1 and YscM2 may be sufficient to activate yop expression.

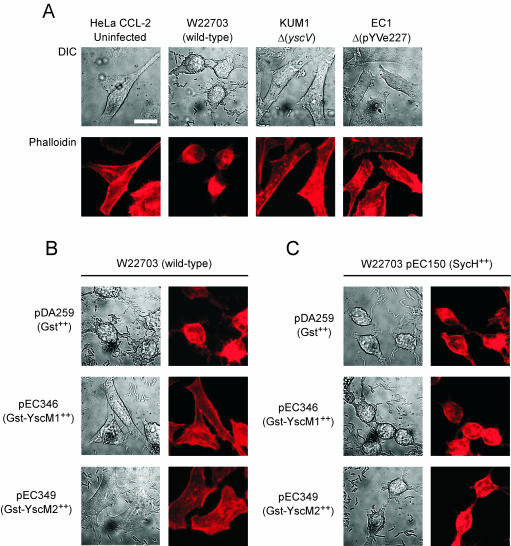

The cytotoxicity of HeLa cells associated with Yersinia infections results in rounding of cells due to cytoskeletal rearrangements, a morphological phenomenon that can be measured through actin staining with fluorophore-conjugated phallotoxins (47). Y. enterocolitica W22703 (wild type), KUM1 (ΔyscV), and EC1 (ΔpYVe227) were used to infect HeLa cells for 3 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized with Triton X-100, and stained with Texas red-conjugated phalloidin. After washing, slides were prepared and viewed by light and fluorescence microscopy. As reported previously, wild-type Yersinia induced cytotoxicity and rounding of HeLa cells (Fig. 6A). The type III secretion-defective mutant KUM1 (ΔyscV) failed to cause cytotoxicity as did EC1 (ΔpYVe227), a strain that lacks the virulence plasmid (Fig. 6A). These data corroborate the previously established notion that tissue culture cytotoxicity is a type III-dependent process requiring the injection of effector Yops (47). When gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 was expressed in wild-type Yersinia during HeLa cell infection, no cytotoxicity was observed (Fig. 6B). This phenotype does not appear to be due to a defect in bacterial adhesion (data not shown) but is likely caused by GST-YscM1- or GST-YscM2-mediated repression of effector yop genes (Fig. 5C). Coexpression of sycH with gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 restored cytotoxicity of HeLa cells (Fig. 6C). Thus, SycH binding to GST-YscM1 or GST-YscM2 is sufficient to induce synthesis and injection of effector Yops or cytotoxicity, consistent with the notion that YscM1 and YscM2, in the abnormal circumstance of SycH overexpression, need not be transported out of the bacterial cytoplasm for SycH-mediated activation of yop expression.

FIG. 6.

SycH binding relieves the block in HeLa cell cytotoxicity imposed by GST-YscM1 or GST-YscM2 expression. (A) Y. enterocolitica strains W22703 (wild type), KUM1 (ΔyscV), and EC1 (ΔpYVe227) were inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers on glass coverslips for 3 h at 37°C. Culture medium was removed, and cells were washed, fixed with formaldehyde, and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100. Samples were blocked with skim milk and labeled with 165 nM Texas red-conjugated phalloidin for 20 min. Label was removed, and samples were washed, aspirated, and dried. Images were captured on an Olympus microscope with a Hamamatsu Ocra digital camera. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were captured at a magnification of ×1,000, and fluorescence was measured at 608-nm emission. Samples were compared with a slide that received no bacteria (uninfected). (B) Y. enterocolitica W22703 harboring plasmid pDA259 (carrying gst), pEC346 (carrying gst-yscM1), or pEC349 (carrying gst-yscM2) was used in HeLa cell infections and stained as described for panel A. (C) Same as for panel B, except that each strain also harbors pEC150 (carrying sycH). Bar, 20 μm.

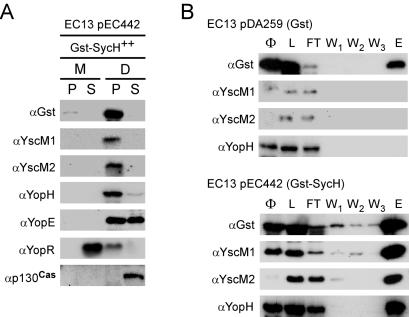

GST-SycH activates Yersinia Yop injection without initiating YscM1, YscM2, and YopH into the type III pathway.

Previous studies demonstrated that fusion of GST to the N terminus of SycE resulted in hybrid chaperones that failed to promote YopE injection during infection, although chaperone binding to substrate remained unaffected (11). To reciprocally examine the interaction between YscM1 or YscM2 with SycH, we expressed gst-sycH (pEC442) in strain EC13 (ΔsycH) (Fig. 7A). When gst-sycH was expressed during infection of HeLa cells, digitonin fractionation revealed that the hybrid protein was expressed and GST-SycH sedimented with adherent bacteria. The expression of gst-sycH abolished the injection of YscM1 and YscM2 and significantly reduced the targeting of YopH, without affecting the synthesis and secretion of YopR or the synthesis and injection of YopE (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 7.

GST-SycH binds YopH, YscM1, and YscM2 without initiating bound polypeptides into the type III pathway. (A) Y. enterocolitica EC13 (ΔsycH) harboring the plasmid pEC442 (carrying gst-sycH) was inoculated into a HeLa cell monolayer for 3 h at 37°C and processed with digitonin fractionation as described for Fig. 1. Protein from each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against GST, YscM1, YscM2, YopH, YopE, YopR, and p130Cas. (B) Y. enterocolitica EC13 harboring the plasmid pDA259 (carrying gst) or pEC442 (carrying gst-sycH) was cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged, and the bacterial pellets were suspended in lysis buffer. Cells were broken in a French pressure cell, lysates (Φ) were centrifuged, and the supernatant was loaded (L) onto glutathione-Sepharose. The flowthrough (FT) was collected, and the columns were washed three times (W1, W2, and W3) with buffer. Columns were eluted (E) with 20 mM glutathione. Protein fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against GST, YscM1, YscM2, and YopH.

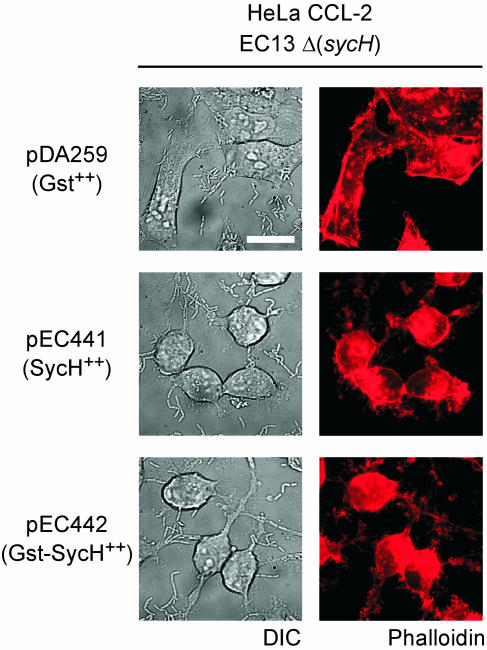

To examine whether GST-SycH binds YscM1, YscM2, and YopH, strain EC13 expressing either gst (pDA259) or gst-sycH was cultured and cells were harvested and lysed. Clarified lysates were subjected to affinity chromatography on glutathione-Sepharose, the columns were washed, and retained peptides were eluted with glutathione (32). SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting revealed that GST-SycH bound YscM1, YscM2, and YopH (Fig. 7B). Thus, even though GST-SycH binds YscM1, YscM2, or YopH, the hybrid chaperone does not initiate bound substrates into the type III injection pathway, similar to GST-SycE. These results also suggest that SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2 activates yop expression without type III transport. We used strain EC13 (ΔsycH) to infect HeLa cells and measured cytotoxicity. When expressing gst alone as a control, strain EC13 was defective for cytotoxicity after 3 h of incubation (Fig. 8). Restoration of cytotoxicity was achieved through the expression of either sycH (pEC441) or gst-sycH (pEC442) (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Cytotoxic defect of sycH mutant yersiniae is relieved by expression of SycH or GST-SycH. Y. enterocolitica strain EC13 (ΔsycH) harboring plasmid pDA259 (carrying gst), pEC441 (carrying sycH), or pEC442 (carrying gst-sycH) was inoculated into HeLa cell monolayers on glass coverslips for 3 h at 37°C and processed as described for Fig. 6. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images were captured at a magnification of ×1,000, and fluorescence was measured at 608-nm emission. Bar, 20 μm.

SycH regulation of yop expression at the level of synthesis, independent of factors regulating secretion.

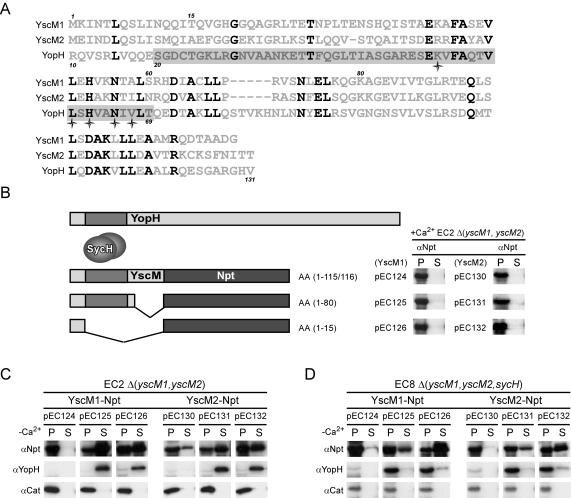

Using yopQ as a model to study regulation, previous work identified Yersinia genes with distinct regulatory functions. Class I genes (yopN, sycN, tyeA, and yscB) regulate YopQ secretion, whereas class II genes (yopD, lcrH, yscM1, and yscM2) regulate YopQ synthesis (2, 9). To categorize sycH by the same parameters, we cultured Y. enterocolitica strains in the presence and absence of calcium and measured YopQ synthesis and secretion (Fig. 9A). As reported earlier, Y. enterocolitica W22703 (wild type) did not synthesize YopQ until induced by the low-calcium signal, resulting in simultaneous synthesis and secretion of the polypeptide. Synthesis of YopQ was severely attenuated in strain EC13 (ΔsycH); however, YopQ secretion was not affected. Furthermore, YopQ was synthesized in the presence of calcium in wild-type yersiniae overexpressing sycH from a plasmid (Fig. 9A). This phenotype is identical to that of the class II mutant strains VTL2 (ΔyopD), CT133 (ΔlcrH), and EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)]. Each of these strains was derepressed for YopQ synthesis, and the regulation of type III secretion was left intact (Fig. 9A). These results suggest that SycH specifically counteracts the function of class II gene product-mediated regulation through its binding to YscM1 or YscM2.

FIG. 9.

YscM1, YscM2, and SycH regulate yop expression independently of type III secretion. (A) Y. enterocolitica strains W22703 (wild type), EC13 (ΔsycH), EC2 [Δ(yscM1, yscM2)], VTL2 (ΔyopD), CT133 (ΔlcrH), VTL1 (ΔyopN), and W22703 harboring the plasmid pEC441 (carrying sycH) were cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) or 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged to separate the bacterial pellet (P) from the culture supernatant (S). Proteins in both fractions were precipitated with TCA and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against YopQ. (B) Y. enterocolitica strains W22703 and EC10 (ΔyopH) were cultured as in panel A, and protein fractions were analyzed with antisera raised against YopQ, YopH, YscM1, YscM2, and SycH. (C) Strain VTL1 harboring the plasmid pDA259 (carrying gst), pEC346 (carrying gst-yscM1), or pEC349 (carrying gst-yscM2) was cultured as descried for panel A. VTL1(pEC346) and VTL1(pEC349) were cultured either with (+) or without (−) pEC150 (carrying sycH). Protein fractions were analyzed with antisera raised against YopQ.

Data described herein suggest that SycH is required for the injection of three different type III substrates. If so, competition of substrate molecules for binding to SycH could function as a switch that controls the amplitude of yop expression. To test this possibility, strain EC10 (ΔyopH) lacking the yopH gene was generated and analyzed for YopQ, YscM1, YscM2, and SycH synthesis and secretion and compared to wild-type yersiniae (Fig. 9B). The expression profile of yopQ in strain EC10 was identical to that of wild-type yersiniae, suggesting that SycH is not sequestered by YopH under calcium-rich conditions. Concentrations of YscM1, YscM2, and SycH were identical in strains EC10 and W22703, a result that is consistent with the notion that changes in the concentration of cognate secretion substrates do not play a role in regulating effector yop expression. It is conceivable that a functional property of SycH may be altered by changes in environmental calcium signals, thereby affecting class II-mediated repression of effector yop genes (Fig. 9B). Alternatively, changes in the intrabacterial concentration of YopH may allow YscM1 and YscM2 binding to SycH.

To examine a genetic relationship between the regulatory function of sycH with low-calcium-response (class I) genes, we analyzed YopQ synthesis and secretion in strain VTL1 (ΔyopN), expressing either gst, gst-yscM1, or gst-yscM2 (Fig. 9C). GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 were both capable of blocking yopQ expression in the class I mutant. It should be noted that GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 are nonfunctional in either VTL2 (ΔyopD) or CT133 (ΔlcrH) (9). YopQ synthesis and secretion were restored when sycH (pEC150) was coexpressed with GST-YscM1 or GST-YscM2 (Fig. 9C). These results indicate that SycH acts at the level of class II-mediated regulation while secretion of Yop proteins is governed by mechanisms that depend on class I genes.

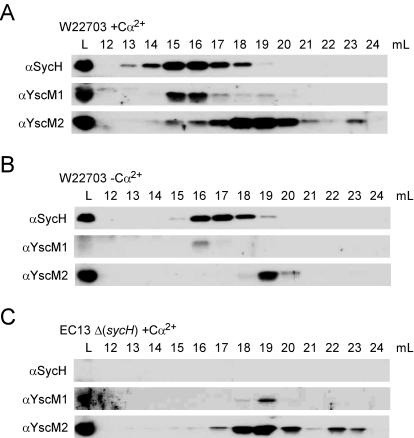

Intracellular association of YscM1 and YscM2 with SycH.

If one presumed YscM1 and YscM2 to exert regulatory functions prior to SycH binding, yersiniae growing in the presence of calcium would be expected to harbor both YscM1 and YscM2 molecules without and with association to SycH (repressing conditions). To test this hypothesis, wild-type Yersinia strain W22703 was cultured in the presence of calcium and cells were harvested and lysed. Clarified lysates were subjected to gel filtration chromatography, and eluate was collected in 1-ml fractions and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 10A). SycH eluted as a peak with most of the immunoreactive material in fractions 15 and 16. YscM1 and YscM2 each separated into two peaks. For YscM1, the majority coeluted with SycH in fractions 15 and 16; however, a second peak with much less immunoreactive material eluted in fraction 19 (Fig. 10A). Most of YscM2 did not coelute with SycH and migrated with major and minor peaks in fractions 19 and 23, respectively (Fig. 10A). These data suggest that while most of YscM1 may be bound to SycH, the majority of YscM2 appears unbound and could be competent for regulation. When cells were grown in the absence of calcium (Fig. 10B), the peak fraction of SycH shifted to 17 while the major peaks of YscM1 and YscM2 remained unaltered. As expected for secretion substrates, the total intracellular population of both factors was greatly reduced under type III secretion conditions. Because the peak fractions of YscM1 and YscM2 did not shift in the absence of calcium, we sought to determine whether coelution of YscM1 and YscM2 with SycH actually represented a YscM-SycH complex. To test this, strain EC13 (ΔsycH) was cultured in the presence of calcium and analyzed similarly to wild-type Yersinia (Fig. 10C). Elution of YscM1 and YscM2 at fraction 16 disappeared, and the entire population of YscM1 shifted to a peak elution at fraction 19, confirming that coelution of YscM1 and YscM2 with SycH at fraction 16 in wild-type Yersinia represents bound complex. These data also explain the hyperrepression phenotype of the EC13 strain. Overall, these experiments suggest that unbound YscM1 and YscM2 may be required for regulation of yop expression.

FIG. 10.

Distribution of intracellular YscM1 and YscM2. (A) Y. enterocolitica W22703 (wild type) was cultured in TSB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 (+Ca2+) for 2 h at 26°C and then induced for type III secretion at 37°C for 3 h. Cultures were centrifuged, and the bacterial pellets were suspended in lysis buffer. Cells were broken in a French pressure cell, lysates were centrifuged, and the supernatant (L) was separated on a Superdex 75 gel filtration column via fast protein liquid chromatography. One-milliliter eluate fractions were collected and represented as milliliters postinjection (lanes 12 to 24). Protein fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antisera (α) raised against SycH, YscM1, and YscM2. (B) Same as for panel A, except strain W22703 was cultured in the presence of 5 mM EGTA (−Ca2+). (C) Strain EC13 (ΔsycH) was cultured and analyzed as describe for panel A.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies proposed that upon calcium signaling, the depletion of LcrQ (YscM1 and YscM2) from the cytoplasm of yersiniae functions as a mechanism to activate effector yop expression (43, 46). Because LcrQ was found to be secreted under low-calcium conditions, it was assumed that yersiniae also secrete LcrQ into the extracellular medium of infected tissue culture cells (43). Recent work suggested that yersiniae perceive a low-calcium signal via the insertion of type III needle complexes into the plasma membrane and cytoplasm of target cells (27, 34). In this model, all substrates that are transported by the type III pathway in response to calcium signaling are expected to travel into the host cell (34). To distinguish between these possibilities, we addressed the subcellular localization of YscM1 and YscM2 during infection of tissue culture cells. Using digitonin fractionation, YscM1 and YscM2 were found to cofractionate with p130Cas, a cytoplasmic factor of eukaryotic cells, and with the injected effectors YopE and YopH. Localization of YscM1 and YscM2 into the digitonin-soluble fraction required SycH, a cytosolic chaperone that is also necessary for the injection of YopH. A new assay was developed to measure the targeting of Yersinia proteins into host cells. FlAsH, a bis-arsenical fluorophore (1), binds to the C-terminal tetracysteine peptide tag of engineered YscM1-Cys4 and YscM2-Cys4 in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, providing for the microscopic detection of injected polypeptides. Taken together, these data suggest that YscM1 and YscM2 are injected into the cytoplasm of tissue culture cells in response to a low calcium signal.

SycH is not required for the negative regulatory properties of YscM1 and YscM2 but is necessary for the injection of the two type III substrates (8, 57). We therefore sought to determine whether SycH contributes to regulating effector yop expression. Previous work demonstrated that GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 prevent effector yop expression (8). It was assumed that this repression is irreversible, as GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 cannot be transported by the type III machinery (8). However, compared to strains expressing only gst-yscM1 and gst-yscM2, coexpression of sycH with either gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 restored synthesis and secretion of effector Yops. These results suggest also that SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2 may function as a mechanism to activate yop expression.

We imagine that YopD, LcrH, YscM1, YscM2, and SycH function together to control effector Yop synthesis prior to host cell contact. This regulatory mechanism implies that the type III apparatus is capable of transporting some Yop proteins prior to host cell contact, which has indeed been observed, as YopB, YopD, YopR, and LcrV are found in the extracellular medium prior to bacterial adherence to target cells (33, 35, 36). Target cell contact and calcium signaling are believed to function as a switch that activates effector Yop synthesis (43). Because SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2 abolishes the repressor function of YopD, LcrH, YscM1, and YscM2, one can view SycH as one of the regulatory molecules involved in flipping the switch. Further, it seems that SycH-mediated regulation does not require transport of YscM1 or YscM2, although type III secretion may contribute to regulation. Three arguments support this conjecture: (i) nonsecretable GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 are inhibited by SycH, (ii) GST-SycH can activate Yop synthesis without targeting YscM1 and YscM2 in host cells, and (iii) SycH-induced synthesis of effector Yops does not require type III transport.

How can Yersinia employ SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2 and activate Yop synthesis in response to bacterial docking on target cells? One possible mechanism could be changes in the concentration of intrabacterial SycH upon target cell contact. In support of this mechanism, it seems important that YopD, LcrH, YscM1, and YscM2 do not regulate sycH expression. Thus, a burst of SycH synthesis or changes in its stability could lead to the activation of Yop synthesis, and future work will need to consider all mechanisms that could increase SycH concentration. Regulation of the activity of SycH binding to YscM1 and YscM2, for example, as a posttranslational chaperone modification, may represent another possible mechanism that has hitherto not been explored.

YopD, LcrH, YscM1, and YscM2 control the synthesis, but not the secretion, of Yop proteins. This is demonstrated through analysis of YopQ synthesis and secretion in the presence of calcium in vitro. Mutations in yopD, lcrH, yscM1, or yscM2 (class II genes) promote the translation of yopQ in the presence of calcium but do not promote secretion under these conditions (9). Expression of sycH in wild-type yersiniae predictably results in the same phenotype, as a sycH mutant strain is defective for YopQ synthesis but not secretion. Synthesis and secretion of YopQ in the presence of calcium is achieved with mutations in yopN, sycN, tyeA, and yscB (class I genes). By expressing gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 in a yopN mutant, it is observed that regulation is left intact. This suggests that SycH functions at the level of Yop synthesis. Further, the observation that GST-YscM1 and GST-YscM2 are functional in a class I mutant suggests that class II-mediated regulation is independent of the circuit that regulates secretion in response to the low-calcium signal. Coexpression of sycH with gst-yscM1 or gst-yscM2 restored synthesis of YopQ, presumably through binding of SycH to YscM1 and YscM2, and the YopQ polypeptide was secreted in the presence of calcium because of the class I mutation. Taken together, these findings suggest that SycH functions exclusively at the level of class II-mediated regulation of type III secretion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deborah Anderson, Vincent Lee, Kumaran Ramamurthi, and Christina Tam for help and reagents.

J.A.S. was supported by the Training Grant in Molecular and Cellular Biology at the University of Chicago. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI42797 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to O.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, S. R., R. E. Campbell, L. A. Gross, B. R. Martin, G. K. Walkup, Y. Yao, J. Llopis, and R. Y. Tsien. 2002. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:6063-6076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, D. M., K. S. Ramamurthi, C. Tam, and O. Schneewind. 2002. YopD and LcrH regulate the expression of Yersinia enterocolitica YopQ at a post-transcriptional step and bind to yopQ mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 184:1287-1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, D. M., and O. Schneewind. 1997. A mRNA signal for the type III secretion of Yop proteins by Yersinia enterocolitica. Science 278:1140-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, D. M., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: an mRNA signal that couples translation and secretion of YopQ. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1139-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuscher, H. U., F. Rodel, A. Forsberg, and M. Rollinghoff. 1995. Bacterial evasion of host immune defense: Yersinia enterocolitica encodes a suppressor for tumor necrosis factor alpha expression. Infect. Immun. 63:1270-1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bliska, J. B., K. Guan, J. E. Dixon, and S. Falkow. 1991. Tyrosine phosphate hydrolysis of host proteins by an essential Yersinia virulence determinant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1187-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boland, A., M.-P. Sory, M. Iriarte, C. Kerbourch, P. Wattiau, and G. R. Cornelis. 1996. Status of YopM and YopN in the Yersinia yop virulon: YopM of Y. enterocolitica is internalized inside the cytosol of PU5-1.8 macrophages by the YopB, D, N delivery apparatus. EMBO J. 15:5191-5201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cambronne, E. D., L. W. Cheng, and O. Schneewind. 2000. LcrQ/YscM1, regulators of the Yersinia yop virulon, are injected into host cells by a chaperone dependent mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 37:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambronne, E. D., and O. Schneewind. 2002. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: yscM1 and yscM2 regulate yop gene expression by a post-transcriptional mechanism that targets the 5′-untranslated region of yop mRNA. J. Bacteriol. 184:5880-5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng, L. W., D. M. Anderson, and O. Schneewind. 1997. Two independent type III secretion mechanisms for YopE in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 24:757-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng, L. W., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: on the role of SycE in targeting YopE into HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22102-22108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornelis, G. R. 2002. Yersinia type III secretion: send in the effectors. J. Cell Biol. 158:401-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelis, G. R., and C. Colson. 1975. Restriction of DNA in Yersinia enterocolitica detected by the recipient ability for a derepressed R factor from Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 87:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deleuil, F., L. Mogemark, M. S. Francis, H. Wolf-Watz, and M. Fallman. 2003. Interaction between the Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH and eukaryotic Cas/Fyb is an important virulence mechanism. Cell. Microbiol. 5:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Lorenzo, V., E. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq /Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evdokimov, A. G., J. E. Tropea, K. M. Routzahn, T. D. Copeland, and D. S. Waugh. 2001. Structure of the N-terminal domain of Yersinia pestis YopH at 2.0 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D 57:793-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francis, M. S., S. A. Lloyd, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2001. The type III secretion chaperone LcrH co-operates with YopD to establish a negative, regulatory loop for control of Yop synthesis in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1075-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaietta, G., T. J. Deernick, S. R. Adams, J. Bouwer, O. Tour, D. W. Laird, G. E. Sosinsky, R. Y. Tsien, and M. H. Ellisman. 2002. Multicolor and electron microscopic imaging of connexin trafficking. Science 296:503-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galan, J. E., and A. Collmer. 1999. Type III secretion machines: bacterial devices for protein delivery into host cells. Science 284:1322-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galyov, E. E., S. Hakansson, A. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1993. A secreted protein kinase of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is an indispensible virulence determinant. Nature 361:730-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goguen, J. D., J. Yother, and S. C. Straley. 1984. Genetic analysis of the low calcium response in Yersinia pestis Mud1(Ap lac) insertion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 160:842-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin, B. A., S. R. Adams, and R. Y. Tsien. 1998. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science 281:269-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakansson, S., T. Bergman, J.-C. Vanooteghem, G. Cornelis, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1993. YopB and YopD constitute a novel class of Yersinia Yop proteins. Infect. Immun. 61:71-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hakansson, S., E. Gaylov, R. Rosqvist, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. The Yersinia YpkA Ser/Thr kinase is translocated and subsequently targeted to the inner surface of the HeLa cell plasma membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 20:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanahan, D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoe, N. P., F. C. Minion, and J. D. Goguen. 1992. Temperature sensing in Yersinia pestis: regulation of yopE transcription by lcrF. J. Bacteriol. 174:4275-4286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoiczyk, E., and G. Blobel. 2001. Polymerization of a single protein of the pathogen Yersinia enterocolitica into needles punctures eukaryotic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4669-4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holmstrom, A., J. Olsson, P. Cherepanov, E. Maier, R. Nordfelth, J. Petterson, R. Benz, H. Wolf-Watz, and A. Forsberg. 2001. LcrV is a channel size-determining component of the Yop effector translocon of Yersinia. Mol. Microbiol. 39:620-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmstrom, A., J. Petterson, R. Rosqvist, S. Hakansson, F. Tafazoli, M. Fallman, K.-E. Magnusson, H. Wolf-Watz, and A. Forsberg. 1997. YopK of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis controls translocation of Yop effectors across the eukaryotic cell membrane. Mol. Microbiol. 24:73-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes, K. T., K. L. Gillen, M. J. Semon, and J. E. Karlinsey. 1993. Sensing structural intermediates in bacterial flagellar assembly by export of a negative regulator. Science 262:1277-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iriarte, M., and G. R. Cornelis. 1998. YopT, a new Yersinia effector protein, affects the cytoskeleton of host cells. Mol. Microbiol. 29:915-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaelin, W. G., W. Krek, W. R. Sellers, J. A. DeCaprio, F. Ajchenbaum, C. S. Fuchs, T. Chittenden, Y. Li, P. J. Farnham, M. A. Blanar, D. M. Livingston, and E. K. Flemington. 1992. Expression cloning of a cDNA encoding a retinoblastoma-binding protein with EF2-like properties. Cell 70:351-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, V. T., D. M. Anderson, and O. Schneewind. 1998. Targeting of Yersinia Yop proteins into the cytosol of HeLa cells: one-step translocation of YopE across bacterial and eukaryotic membranes is dependent on SycE chaperone. Mol. Microbiol. 28:593-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, V. T., S. K. Mazmanian, and O. Schneewind. 2001. A program of Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion reactions is triggered by specific host signals. J. Bacteriol. 183:4970-4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, V. T., and O. Schneewind. 1999. Type III machines of pathogenic yersiniae secrete virulence factors into the extracellular milieu. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1619-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, V. T., C. Tam, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion. LcrV, a substrate for type III secretion, is required for toxin-targeting into the cytosol of HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:36869-36875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lloyd, S. A., M. Norman, R. Rosqvist, and H. Wolf-Watz. 2001. Yersinia YopE is targeted for type III secretion by N-terminal, not mRNA, signals. Mol Microbiol. 39:520-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michiels, T., P. Wattiau, R. Brasseur, J.-M. Ruysschaert, and G. Cornelis. 1990. Secretion of Yop proteins by yersiniae. Infect. Immun. 58:2840-2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mills, S. D., A. Boland, M.-P. Sory, P. van der Smissen, C. Kerbouch, B. B. Finlay, and G. R. Cornelis. 1997. Yersinia enterocolitica induces apoptosis in macrophages by a process requiring functional type III secretion and translocation mechanisms and involving YopP, presumably acting as an effector protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:12638-12643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monack, D. M., J. Mecsas, N. Ghori, and S. Falkow. 1997. Yersinia signals macrophages to undergo apoptosis and YopJ is necessary for this cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10385-10390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilles, M. L., K. A. Fields, and S. C. Straley. 1998. The V antigen of Yersinia pestis regulates Yop vectorial targeting as well as Yop secretion through effects on YopB and LcrG. J. Bacteriol. 180:3410-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Persson, C., R. Nordfelth, A. Holmstrom, S. Hakansson, R. Rosqvist, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1995. Cell-surface-bound Yersinia translocate the protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH by a polarized mechanism into the target cell. Mol. Microbiol. 18:135-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petterson, J., R. Nordfelth, E. Dubinina, T. Bergman, M. Gustafsson, K. E. Magnusson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1996. Modulation of virulence factor expression by pathogen target cell contact. Science 273:1231-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pollack, C., S. C. Straley, and M. S. Klempner. 1986. Probing the phagolysosomal environment of human macrophages with a Ca2+-responsive operon fusion in Yersinia pestis. Nature 322:834-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramamurthi, K. S., and O. Schneewind. 2002. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion: mutational analysis of the yopQ secretion signal. J. Bacteriol. 184:3321-3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rimpilainen, M., A. Forsberg, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1992. A novel protein, LcrQ, involved in the low-calcium response of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis shows extensive homology to YopH. J. Bacteriol. 174:3355-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosqvist, R., A. Forsberg, M. Rimpilainen, T. Bergman, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1990. The cytotoxic protein YopE of yersinia obstructs the primary host defense. Mol. Microbiol. 4:657-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosqvist, R., K.-E. Magnusson, and H. Wolf-Watz. 1994. Target cell contact triggers expression and polarized transfer of Yersinia YopE cytotoxin into mammalian cells. EMBO J. 13:964-972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith, C. L., P. Khandelwal, K. Keliikuli, E. R. Zuiderweg, and M. A. Saper. 2001. Structure of the type III secretion and substrate binding domain of Yersinia YopH phosphatase. Mol. Microbiol. 42:967-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sory, M.-P., A. Boland, I. Lambermont, and G. R. Cornelis. 1995. Identification of the YopE and YopH domains required for secretion and internalization into the cytosol of macrophages, using the cyaA gene fusion approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11998-12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sory, M.-P., and G. R. Cornelis. 1994. Translocation of a hybrid YopE-adenylate cyclase from Yersinia enterocolitica into HeLa cells. Mol. Microbiol. 14:583-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stainier, I., M. Iriarte, and G. R. Cornelis. 1997. YscM1 and YscM2, two Yersinia enterocolitica proteins causing downregulation of yop transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 26:833-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wattiau, P., and G. R. Cornelis. 1993. SycE, a chaperone-like protein of Yersinia enterocolitica involved in the secretion of YopE. Mol. Microbiol. 8:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wattiau, P., S. Woestyn, and G. R. Cornelis. 1996. Customized secretion chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 20:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams, A. W., and S. C. Straley. 1998. YopD of Yersinia pestis plays a role in negative regulation of the low-calcium response in addition to its role in translocation of Yops. J. Bacteriol. 180:350-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woestyn, S., M.-P. Sory, A. Boland, O. Lequenne, and G. R. Cornelis. 1996. The cytosolic SycE and SycH chaperones of Yersinia protect the region of YopE and YopH involved in translocation across eukaryotic cell membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1261-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wulff-Strobel, C. R., A. W. Williams, and S. C. Straley. 2002. LcrQ and SycH function together at the Ysc type III secretion system in Yersinia pestis to impose a hierarchy of secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 43:411-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]