Abstract

The connection between peptidoglycan remodeling and cell division is poorly understood in ellipsoid-shaped ovococcus bacteria, such as the human respiratory pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. In S. pneumoniae, peptidoglycan homeostasis and stress are regulated by the WalRK (VicRK) two-component regulatory system, which positively regulates expression of the essential PcsB cysteine- and histidine-dependent aminohydrolases/peptidases (CHAP)-domain protein. CHAP-domain proteins usually act as peptidoglycan hydrolases, but purified PcsB lacks detectable enzymatic activity. To explore the functions of PcsB, its subcellular localization was determined. Fractionation experiments showed that cell-bound PcsB was located through hydrophobic interactions on the external membrane surface of pneumococcal cells. Immunofluorescent microscopy localized PcsB mainly to the septa and equators of dividing cells. Chemical cross-linking combined with immunoprecipitation showed that PcsB interacts with the cell division complex formed by membrane-bound FtsXSpn and cytoplasmic FtsESpn ATPase, which structurally resemble an ABC transporter. Far Western blotting showed that this interaction was likely through the large extracellular loop of FtsXSpn and the amino terminal coiled-coil domain of PcsB. Unlike in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli, we show that FtsXSpn and FtsESpn are essential in S. pneumoniae. Consistent with an interaction between PcsB and FtsXSpn, cells depleted of PcsB or FtsXSpn had strikingly similar defects in cell division, and depletion of FtsXSpn caused mislocalization of PcsB but not the FtsZSpn early-division protein. A model is presented in which the interaction of the FtsEXSpn complex with PcsB activates its peptidoglycan hydrolysis activity and couples peptidoglycan remodeling to pneumococcal cell division.

Keywords: WalRKSpn (VicRK) regulon, cell wall biosynthesis, cell surface protein, murein hydrolysis

Ovococcus bacteria are ellipsoid-shaped like American footballs and include Streptococcus and Lactococcus species that are important as mammalian pathogens and in industry (1–3). Of this group, S. pneumoniae is a serious human pathogen that causes pneumonia, otitis media, meningitis, and septicemia, and it annually kills more than 1.6 million people worldwide (4–6). The compositions of the supramolecular machineries that mediate peripheral and septal peptidoglycan (PG) synthesis in ovococci are only starting to emerge (7–11). However, relatively little is known about the roles of PG hydrolases in cell division as opposed to autolysis or competence-dependent fratricide (12–15). The PcsB protein in S. pneumoniae has been a leading candidate for a PG hydrolase involved in cell division (12, 13, 16–19).

PcsB emerged as a candidate PG hydrolase in cell division, because it is essential in serotype 2 strain D39 and possibly other serotypes of S. pneumoniae (Discussion) (16, 18, 19). Consistent with its essential role, the amino acid sequence of PcsB is highly conserved in all serotypes of S. pneumoniae, much more so than the amino acid sequences of surface virulence factors (17). The pcsB gene is the only essential member of the regulon controlled by the WalRKSpn (VicRK) two-component system (Fig. 1). The WalRKSpn regulon also includes genes encoding other nonessential PG hydrolases (12, 19, 20). Depletion of PcsB or WalRKSpn leads to an arrest of cell growth and the development of misshapen cells with severe division and PG biosynthesis defects (16, 18, 19). Consistent with this regulatory linkage, constitutive expression of pcsB from a synthetic promoter uncouples pcsB expression from the WalRKSpn two-component system and renders the WalRSpn (VicR) response regulator nonessential (19).

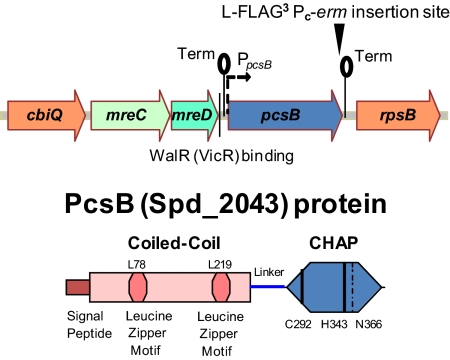

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagrams of the pneumococcal pcsB operon and the PcsB protein. pcsB is a single gene operon between mreCD and rpsB that is regulated positively by the WalRSpn response regulator, which binds upstream of the PpcsB promoter (8). Putative transcription terminators (lollipops) and the insertion point that creates the PcsB-l-FLAG3 fusion protein and adds the selectable Pc-erm marker are indicated. The PcsB polypeptide contains the following segments: a signal peptide that is cleaved off during export (16), a coiled-coil domain containing two putative leucine zipper motifs, an alanine-rich linker, and a CHAP domain containing a characteristic catalytic triad of 3 aa (Cys292-His343-N366). Simultaneous L78S and L219P amino acid changes in the putative leucine zipper motifs of the coiled-coil domain cause a temperature-sensitive phenotype. Additional details in the text.

The domain structure of PcsBSpn is also suggestive of a PG hydrolase. The PcsBSpn polypeptide consists of four segments: a conventional signal peptide domain that is cleaved off during secretion (16), an extended coiled-coil domain containing putative leucine zipper motifs, a variable alanine-rich linker region, and a putative cysteine- and histidine-dependent aminohydrolases/peptidases (CHAP) domain (Fig. 1). CHAP domains contain a cysteine–histidine–asparagine triad in their active sites that resembles the fold of papain proteases (21–23). In bacteriophage lysins, CHAP domains function as PG amidases and endopeptidases (24–26). By comparison, the functions of only a couple bacterial CHAP domain proteins have been characterized (16, 27–29). Like PcsB homologs in Streptococcus species, the Sle1 CHAP-domain protein of Staphylococcus aureus seems to play fundamental roles in cell division (28). KO mutants of sle1 have been reported that are severely impaired for cell division and growth (28). Purified Sle1 protein lacking its signal peptide and the Sle1 CHAP domain alone both exhibited robust hydrolase activity on S. aureus PG in zymograms (28). In addition, purified Sle1 protein reduced the turbidity of S. aureus PG preparations and released dimer PG peptides, consistent with an activity as an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase (i.e., Sle1 cleaves the amide bond between N-acetyl-muramic acid in the glycan chain and l-Ala in PG peptides that are cross-linked as dimers) (28).

In contrast, there has not been a convincing demonstration of PG hydrolase activity by any PcsB homolog from a Streptococcus species. In S. pneumoniae, Cys292Ala and His343Ala mutations in PcsB are not tolerated (18), suggesting that the CHAP-domain catalytic amino acids are required for PcsB function in cells. However, several different PG hydrolysis assay formats have failed to show activity of purified PcsB (16, 30). Recently, weak PG hydrolytic activity was reported in zymograms for the PcsB homolog, called CdhA, of S. pyogenes (31). However, the critical control was not included, showing loss of activity of mutant proteins containing amino acid changes of the catalytic cysteine or histidine. Some other properties suggest that PcsB may also play a scaffolding role in cell division complexes. Curiously, less than one-half of PcsB typically remains bound to cells grown in culture, and the rest of the PcsB is secreted into the medium (16, 30, 32). Secretion of substantial amounts of PcsB homologs into the culture medium was reported for other bacterial species in a strain- and medium-dependent manner (32–34). Cell-bound PcsB is an abundant protein of ∼5,000 monomers per cell (16), consistent with a role in complex formation. Finally, although the Cys292 and His343 catalytic amino acids are essential in PcsB, unexpectedly, an Asn366Ala change is tolerated. This result suggests that if the CHAP domain of PcsB is a PG amidase, then another amino acid can substitute for the conserved Asn in the catalytic triad.

A previous report showed that PcsB is likely membrane-bound (32). During secretion, the signal peptide is fully removed from cell-bound and secreted PcsB (16). Processed PcsB is not a hydrophobic protein and lacks predicted amphipathic helices. Therefore, we hypothesized that PcsB must interact with a membrane-bound protein on the outside cell surface. If PcsB PG hydrolase activity strictly depended on such an interaction, it would account for the lack of PG hydrolase activity of purified PcsB. Likewise, protein interactions are implicit to the hypothesis that PcsB acts as a scaffold or regulatory protein. A corollary of these hypotheses is that the PcsB interactor protein would itself be essential. In this paper, we used unbiased chemical cross-linking and immunoprecipitation approaches to show that PcsB interacts on the pneumococcal cell surface with the FtsXSpn integral membrane protein, which in turn, interacts with the cytoplasmic FtsESpn protein. We also show that both FtsXSpn and FtsESpn are essential and that this interaction directs PcsB to equatorial and septal sites of dividing cells. A model is proposed in which the PG hydrolytic activity of PcsB is dependent on its interaction with the FtsEXSpn complex, which interacts with the FtsZSpn-dependent divisome.

Results

PcsB Is Bound on the Outer Surface of the Cell Membrane by Hydrophobic Interactions.

PcsB was epitope-tagged with two versions of the FLAG tag (DYKDDDDK) to aid in detection and pull-down experiments. One construct (PcsB-FLAG) has the 8-aa FLAG tag (16), and the other (PcsB-l-FLAG3) has a 10-aa linker (l) followed by three tandem copies of FLAG (35) fused to the carboxyl terminus of PcsB (Table S1). Each construct was expressed from the native chromosomal pcsB locus of laboratory strain R6 or an unencapsulated derivative of strain D39 (Table S1). Western blotting with anti-PcsB antibody showed that both PcsB-FLAG and PcsB-l-FLAG3 are stable, and no loss of the epitope tag was detected in pneumococcal extracts (Fig. S1) (16). Neither fusion caused any defect in cell growth, cell division, or morphology or the relative amount of PcsB secreted into the culture medium compared with parent strains (see below) (16). Because a modest decrease of less than fourfold of the cellular PcsB amount results in observable division and morphology defects (16), we conclude that the PcsB-FLAG and PcsB-l-FLAG3 fusions are functional.

To better understand PcsB binding to pneumococcal cells, we first performed a series of subcellular fractionation and wash experiments. For strain IU1845 (R6 PcsB-FLAG) growing exponentially in brain–heart infusion (BHI) broth (Materials and Methods), cell-bound PcsB-FLAG was recovered only from the membrane fraction (Fig. 2A), consistent with a previous report (32). Membrane binding of PcsB-FLAG rather than aggregation and precipitation during fractionation was also confirmed by cosedimentation of PcsB-FLAG and membranes in sucrose step gradients (35). We did not detect any PcsBSpn in the cell wall fraction. This result contrasts with earlier reports that the PcsB homologs of S. agalactiae and S. mutans fractionate in both the cell wall and membrane fractions (33, 36). In our fractionation procedure, we digested away cell walls for a longer period with a combination of mutanolysin and lysozyme than in these earlier studies, and we confirmed microscopically that all digested cells formed spherical protoplasts that lysed on hypotonic treatment (Materials and Methods).

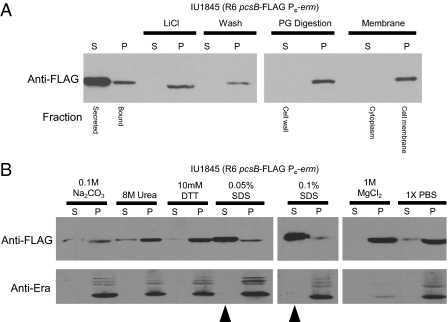

Fig. 2.

PcsB binds to the outer surface of the cell membrane by hydrophobic interactions. (A) Fractionation of S. pneumoniae cells after PcsB-FLAG by Western blotting using anti-FLAG antibody. Supernates (S) or pellets (P) are marked for centrifugation steps, and cell fractions are indicated below the blots. Strain IU1845 was grown exponentially and fractionated as described in Materials and Methods. Secreted PcsB-FLAG was recovered from the culture supernatant by TCA precipitation. Bound PcsB-FLAG was from cell pellets, which were washed briefly with 5 M LiCl or digestion buffer. Washed cells were digested with mutanolysin and lysozyme (PG digestion lanes), and protoplasts were lysed by adding hypotonic buffer (membrane lanes). (B) Release of PcsB-FLAG from the cell surface of IU1845 was performed by washing with the chemicals indicated. Exponentially grown strain IU1845 was washed, and cell-bound (P) or released (S) PcsB-FLAG was detected by Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. Released PcsB-FLAG was recovered from supernates by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation. Disruption of cell membrane was monitored by release of intracellular Era protein with anti-Era antibody (38). Arrows indicate large releases of PcsB-FLAG from cell surfaces by low concentrations of SDS that did not disrupt cell membranes. The experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Cells were washed briefly with several chemicals to try to release PcsB-FLAG from the membrane surface (37). Strong ionic washes (5.0 M LiCl or 1.0 M MgCl2) or chemical reagents that disrupt covalent disulfide (DTT) or thioester linkages (100 mM Na2CO3) did not remove substantial amounts of PcsB-FLAG from the cell surface (Fig. 2 A and B). Control experiments in which Western blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-Era antibody showed that none of these conditions released Era protein from its locations in the cytoplasm and inner membrane (Fig. 2B) (38). Even brief treatment with a strong chemical denaturant (8.0 M urea) only released ∼25% of PcsB-FLAG from pneumococcal cell surfaces (Fig. 2B). In contrast, very low concentrations of detergent [0.05% or 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS] released almost all of the PcsB-FLAG from cell surfaces but none of the cytoplasmic Era (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained when purified cell membranes were washed with the same chemicals (Fig. S2), confirming that the pneumococcal cell wall did not block PcsB release from the whole cells. We conclude that hydrophobic interactions make a major contribution to the binding of PcsB-FLAG to the outer membrane surface of pneumococcal cells.

PcsB Interacts with the FtsEXSpn Complex in Cell Membranes.

To identify PcsB interactors, we used reversible chemical cross-linking to stabilize complexes followed by pull down of FLAG-tagged proteins. Unencapsulated strain IU3126 (R6 PcsB-l-FLAG3) was grown exponentially and treated briefly with 0.1% (wt/vol) formaldehyde, and PcsB-l-FLAG3 was pulled down with anti-FLAG agarose from purified membranes as described in Materials and Methods. In Western blots with anti-FLAG antibody, a single PcsB-l-FLAG3 band was detected in cross-linked samples that had been heated (Fig. 3A). In samples that were not heated, a prominent complex that included PcsB-l-FLAG3 was detected with a mass of ∼100 kDa. A distinct, less prominent complex was also detected with a mass of ∼120 kDa as well as some complexes with higher molecular masses. We cut out the 100- and 120-kDa bands, removed the cross-links by heating, and determined the compositions of the bands by MALDI MS as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, we identified several proteins with molecular masses corresponding to the size of these bands. In addition, we detected prominent tryptic fragments corresponding to the smaller proteins: PcsB (41.0 kDa) and FtsXSpn (34.3 kDa) or PcsB, FtsXSpn, and FtsESpn (25.8 kDa) in the 100- or 120-kDa bands, respectively (Fig. 2A). No other prominent tryptic fragments corresponding to smaller proteins were detected. We conclude that the major 100-kDa band contains a complex of PcsB and FtsXSpn, likely in a stoichiometry of 1:2, respectively, and the 120-kDa band contains a complex of PcsB, FtsXSpn, and FtsESpn, likely in a stoichiometry of 1:2:1, respectively.

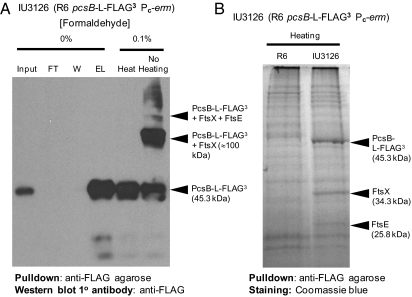

Fig. 3.

PcsB forms a complex with division proteins FtsEXSpn in cell membranes. (A) Pull down of PcsB-l-FLAG3 complexes in membranes of exponentially growing cells that were treated with formaldehyde are shown, which was described in Materials and Methods. Bands on Western blots were detected with anti-FLAG antibody. Left lanes, samples that were not cross-linked. FT, flow-through fractions; W, washed fractions; EL, eluted fractions. Right lanes, cross-linked samples that were heated to break cross-links or not heated to maintain complexes. The composition of the bands was determined by MALDI MS as described in Materials and Methods. The experiment was done two times with similar results. (B) Pull down of cross-linked PcsB-l-FLAG3 complexes in membranes detected by Coomassie blue staining. Samples were prepared, heated to break cross-links, and resolved by SDS/PAGE as described in the text and Materials and Methods. Left lane, extract from R6 control strain that does not express a FLAG-tagged protein. Right lane, extract from strain IU3126 expressing PcsB-l-FLAG3. The unique pull-down bands are indicated, and their identities were confirmed by MALDI MS. The experiment was performed three times with similar results.

To confirm this conclusion, we pulled down PcsB-l-FLAG3 from membrane fractions of cross-linked cells, removed cross-links by heating, and located possible interactors on SDS/PAGE gels stained with Coomassie dye (Fig. 3B). To reduce background, we filtered eluents of anti-FLAG affinity columns through 100-kDa cutoff filters before removing cross-links. Even with this treatment, numerous faint background bands were detected by general Coomassie staining in pull-down samples of the R6 control strain not expressing PcsB-l-FLAG3 (Fig. 3B, left lane). Nevertheless, the pull-down samples from the strain expressing PcsB-l-FLAG3 contained three prominent bands not present in the control extracts (Fig. 3B, right lane). MALDI MS identified these three bands as PcsB-l-FLAG3, FtsXSpn, and FtsESpn. Together, these results support the conclusion that PcsB is in a complex with membrane division protein FtsXSpn, which in turn, binds to cytoplasmic FtsESpn (Discussion) (39–41).

The conclusion that PcsB forms a complex with FtsEXSpn was also confirmed by a reciprocal pull-down experiment of FtsESpn. Cytoplasmic FtsE family proteins are ATPase subunits that form a complex with cognate integral membrane FtsX proteins, and these complexes resemble an ABC transporter (39–41). We show below that FtsXSpn and FtsESpn are essential proteins in S. pneumoniae. We were unable to construct an active tagged version of FtsXSpn. However, we were able to construct an active FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 fusion under the control of the fucose-inducible PfcsK promoter in the ectopic bgaA site (Fig. S4 and Table S1) (12, 42). We expressed FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 ectopically, because ftsESpn-ftsXSpn forms an operon with overlapping translational signals, and it was unlikely that we could construct a carboxyl terminal fusion to FtsESpn without disrupting the translation of FtsXSpn.

The ftsE+//PfcsK-ftsE-l-FLAG3 merodiploid and a ΔftsE//PfcsK-ftsE-l-FLAG3 mutant grew normally in the presence of fucose, indicating that FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 was functional and complemented the ΔftsE deletion. The ftsE+//PfcsK-ftsE-l-FLAG3 merodiploid strain was grown exponentially, cells were treated with formaldehyde, and FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 was pulled down as described in Materials and Methods. Cross-linked FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 was detected in higher molecular mass complexes of ≥100 kDa on Western blots with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. S4A, lane 4). Control experiments showed no complexes of FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 in extracts of cells that were not treated with formaldehyde (Fig. S4A, lane 2), and no signal was detected for the parent strain that does not express FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 (Fig. S4A, lanes 1 and 3). Samples containing cross-linked FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 were heated, and Western blots were performed with anti-PcsB antibody (16). A PcsB band was readily detected from the strain expressing FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 (Fig. S4B, lane 2) but not in the control experiment using a strain that does not express FtsESpn-l-FLAG3 (Fig. S4B, lane 1). These results strongly support the idea that FtsESpn and PcsB are in the same membrane-bound complex with FtsXSpn.

Large Extracellular Loop of FtsXSpn Interacts with the Coiled-Coil Domain of PcsB.

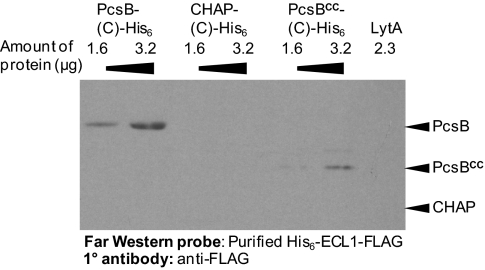

Sequence alignments and the TMHMM program (43) suggest that FtsXSpn has a similar topology as the topology determined experimentally for FtsXEco (39). The 34.3-kDa FtsXSpn protein likely contains four transmembrane domains interspersed with one large extracellular loop (ECL1; 15.9 kDa) and one smaller ECL (ECL2; 3.0 kDa) extracellular domains. We tested for interactions between purified PcsB lacking its signal peptide and ECL1Spn by Far Western blotting (Fig. 4 and Materials and Methods). PcsB protein bound to ECL1 in this assay (Fig. 4, columns 1 and 2). Control experiments showed that ECL1 did not bind to the purified LytA amidase (Fig. 4, column 7) or DacA dd-carboxypeptidase, and no signal was detected on the blots when purified ECL1 or primary anti-FLAG antibody was omitted. We could not test binding between PcsB and ECL2 by this method, because ECL2-His6-FLAG became insoluble after purification. We cloned and purified the separate coiled-coil (CC) domain and CHAP domains of PcsB (Fig. 1 and Table S1). In Far Western blots, we could detect binding of ECL1 to the CC domain (Fig. 4, columns 5 and 6) but not the CHAP domain (Fig. 4, columns 3 and 4) of PcsB. Together, these results support the hypothesis that the ECL1 domain of FtsXSpn specifically interacts with the CC domain of PcsB.

Fig. 4.

Purified PcsB and the coiled-coil (CC) domain of PcsB, but not the CHAP domain of PcsB, interacts with purified ECL1 of FtsXSpn. Proteins were purified, and Far Western blots were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The blot contains the amounts of purified proteins indicated at the top. The blot was probed with purified ECL1-FLAG protein and developed with anti-FLAG antibody. The expected position on the blot of PcsB-His6, PcsBCC-His6, and the CHAP domain are indicated. LytA should run between PcsBCC-His6 and PcsB-His6. No signal was detected on control blots when purified ECL1 or primary anti-FLAG antibody was omitted. The experiment was performed three times with similar results.

FtsXSpn and FtsESpn Are Essential and Depletion of FtsXSpn Phenocopies Depletion of PcsB.

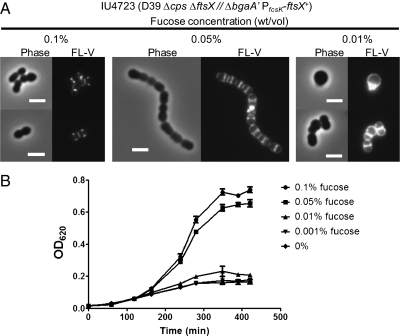

FtsXSpn and FtsESpn were categorized as likely essential in a global transposon mutagenesis study of serotype 4 strain TIGR4 (44). Consistent with this interpretation, we could not construct deletion/insertion mutations in ftsESpn or ftsXSpn in an unencapsulated derivative of serotype 2 strain D39, unless ftsE+Spn or ftsX+Spn, respectively, was also expressed from an ectopic locus (Fig. 5). Additional confirmation of the essentiality of ftsXSpn was obtained by titrating the expression of FtsXSpn in a D39 Δcps ΔftsX//PfcsK-ftsX+ merodiploid strain (Fig. 5). At concentrations of fucose >0.1% (wt/vol), the phenotypes of the unencapsulated ftsX merodiploid strain were indistinguishable from those phenotypes of its D39 Δcps ftsX+ parent; both strains grew with similar doubling times and formed diplococci, whose septa and equators stained with fluorescent vancomycin (FL-V), which binds to PG pentapeptides ending in d-Ala-d-Ala in regions of active PG synthesis in growing WT cells (Fig. 5A, Left) (16, 18, 19). At 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose, FtsXSpn underexpression caused chaining, rounding of cells, and thick equatorial staining with FL-V, although the growth rate and yield of the ftsX merodiploid were only slightly reduced compared with the growth rate and yield of the parent strain (Fig. 5A, Center). Continued depletion of FtsXSpn halted growth and led to the formation of nearly spherical cells that contained aberrant division septa and peripheral staining with FL-V (Fig. 5A, Right). The growth and cell morphology defects caused by depletion of FtsXSpn are similar to those defects caused by depletion of PcsB (16, 18). We attempted to perform parallel titration experiments using a D39 Δcps ΔftsE//PfcsK-ftsE+ merodiploid strain. The ectopic copy of ftsE+ complemented the ΔftsE mutation and allowed growth, but we were unable to reduce ectopic expression of FtsESpn sufficiently to interfere with growth. This topic was not pursued more in this study, because we conclusively showed that FtsXSpn and FtsESpn are essential for normal growth and division of S. pneumoniae. Moreover, the similar defects in cell morphology caused by depletion of FtsXSpn or PcsB support the hypothesis that both proteins function in the same pathway.

Fig. 5.

Defective cell morphology and FL-V staining and impaired growth caused by depletion of FtsXSpn. (A) Morphology of cells depleted of FtsXSpn. Depletion of FtsXSpn was brought about in ftsX merodiploid strain IU4723 (D39 Δcps ΔftsX// PfcsK-ftsX+) by decreasing the concentration of fucose in the culture medium as described in Materials and Methods. Samples were taken for phase-contrast microscopy or staining with FL-V and observation by epifluorescent microscopy at OD620 ∼ 0.2 for cultures containing 0.05% or 0.1% (wt/vol) fucose or 300 min after fucose was removed completely from the culture medium. (B) Growth curve (linear scale) of strain IU4723 depleted for FtsXSpn. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. (Scale bar, 2 μm.)

PcsB Localizes to Equators and Division Septa and Becomes Mislocalized on FtsXSpn Depletion.

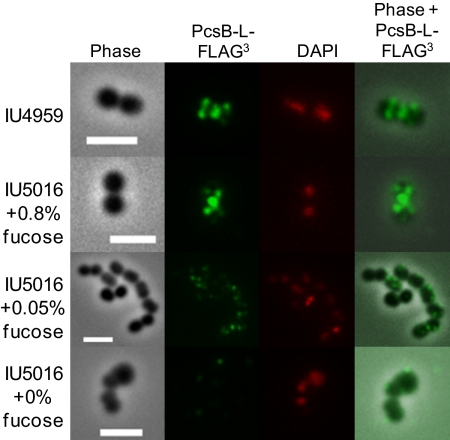

The FtsEXEco complex of Escherichia coli interacts with the FtsZEco divisome apparatus (39, 45, 46). Therefore, if pneumococcal PcsB and FtsXSpn interact, then we would expect preferential localization of PcsB to division sites, and FtsXSpn depletion should lead to mislocalization of PcsB. We performed immunofluorescent microscopy (IFM) to localize PcsB. IFM with anti-PcsB did not produce strong signals or consistent results. Consequently, we localized PcsB-l-FLAG3 expressed from the native pcsB locus (Fig. 1) with anti-FLAG antibody (Materials and Methods). As mentioned above, cells expressing PcsB-l-FLAG3 from its native locus were indistinguishable from their parent strains. PcsB-l-FLAG3 consistently localized to septa, equators, or both places in ∼77% of 87 dividing cells that were scored (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3A). In S. pneumoniae, these sites of PG synthesis are indicated by FL-V staining (Fig. 5A, Left) (16, 18, 19) and FtsZSpn localization (Fig. S5, Left) (47–49). Lower amounts of PcsB-l-FLAG3 were sometimes detected at other locations around cells but not as prominently as at the septa and equators. So far, we have not discerned a pattern for this weaker localization of PcsB-l-FLAG3. In ∼23% of scored cells, PcsB-l-FLAG3 was present faintly in no discernable pattern at all. We conclude that PcsB preferentially localizes to sites of active PG synthesis and cell division at the septa and equators; however, this localization may be dynamic, and therefore, PcsB is occasionally observed in lower amounts at other cellular locations.

Fig. 6.

Localization of PcsB to equators and septa of dividing pneumococcal cells depends on FtsXSpn. Strains IU4959 (D39 Δcps pcsB-l-FLAG3) and IU5016 (D39 Δcps pcsB-l-FLAG3 ΔftsX::P-aad9// PfcsK-ftsX+) were grown exponentially, FtsXSpn was depleted in strain IU5016, and IFM with anti-FLAG antibody and staining with DAPI were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative images are shown from three independent experiments. Column 1, phase-contrast images showing cell outlines; column 2, location of PcsB-l-FLAG3 (pseudocolored green); column 3, DAPI staining of DNA nucleoids (pseudocolored red); column 4, overlaid images of columns 1 (phase) and 2 (PcsB-l-FLAG3). (Scale bar, 2 μm.) Additional details in the text.

We found that PcsB-l-FLAG3 mislocalized from the septa and equators on depletion of FtsXSpn. In BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose, PcsB-l-FLAG3 localized to the septa and equators in ftsX merodiploid strain IU5016 (D39 Δcps pcsB-l-FLAG3 ΔftsX::Pc-aad9//PfcsK-ftsX+) (Fig. S3B), similar to isogenic control strain IU4959 (D39 Δcps pcsB-l-FLAG3 ftsX+) (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3A). In 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose, the ftsX merodiploid strain grew only slightly worse than in fucose concentrations >0.1% (wt/vol) (Fig. 5). However, cells started to chain, and PcsB-l-FLAG3 was not localized or even visible in many cells (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3C). In BHI broth lacking fucose, the ftsX merodiploid strain stopped growing, and relatively little PcsB-l-FLAG3 was detected in any of the cells (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3D). As a control, we followed the localization of an FtsZSpn-mCherry fusion expressed from its native chromosome locus in ftsX merodiploid strain IU5150 (D39 Δcps ftsZ-mCherry ΔftsX::Pc-aad9//ΔbgaA′ PfcsK-ftsX+). The FtsZSpn-mCherry fusion protein did not cause cell morphology defects or temperature sensitivity (Fig. S5, Left) and localized to the midcell regions of dividing cells, which was reported previously for FtsZSpn in S. pneumoniae (47–49). Depletion of FtsXSpn caused division defects, but FtsZSpn-mCherry continued to localize to midcells on moderate depletion of FtsXSpn (Fig. S5, Center), which caused PcsB-l-FLAG3 mislocalization (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3C). Even on severe depletion of FtsXSpn, FtsZSpn-mCherry could occasionally be seen at midcells, although it also appeared mislocalized in many cells (Fig. S5, Right).

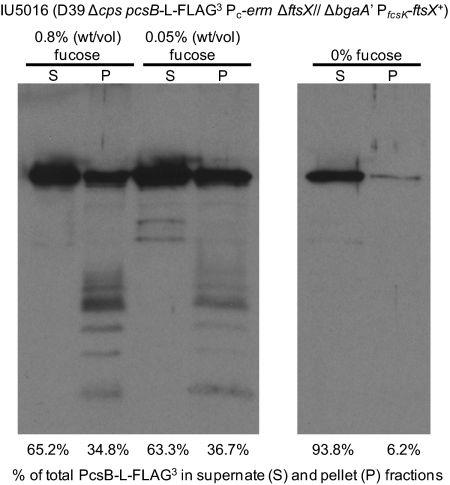

Last, we tested whether severe depletion of FtsXSpn led to release of PcsB-l-FLAG3 from cells (Fig. 7). To maximize depletion of FtsXSpn in this experiment, we first grew the ftsXSpn merodiploid strain in 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose and then shifted it to medium lacking fucose (Materials and Methods). PcsB-l-FLAG3 was largely released into the medium when FtsXSpn was severely depleted under these conditions (Fig. 7, Right), which still did not cause overt lysis of cells. Thus, depletion of FtsXSpn led to mislocalization of PcsB, even when the FtsZSpn division protein, which likely interacts with the FtsEXSpn complex, continued to localize to midcells. Together, these results support the contention that PcsB and FtsXSpn interact.

Fig. 7.

PcsB-l-FLAG3 is released to the culture medium when FtsXSpn is severely depleted. Strain IU5016 was grown in BHI broth supplemented with 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose at 37 °C and diluted into fresh BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose, 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose, or no fucose as described in Materials and Methods. When cultures reached early exponential phase (OD620 ∼ 0.2) or after ∼300 min, whichever came first, cells were collected by centrifugation, and PcsB-l-FLAG3 released to culture supernates (S) or in cell pellets (P) was detected by Western blotting using anti-PcsB antibody as described in the Materials and Methods. Percentages of total PcsB-l-FLAG3 in each sample in the supernatant (S) or pellet (P) are indicated. Phase-contrast microscopic examination of cells at the time samples taken for Western blotting did not reveal obvious lysis. Comparable results were obtained in three independent experiments.

CC Domain of PcsB Is Essential for Function.

Because of its interaction with FtsXSpn, the CC domain of PcsB should be essential for function and cell growth. To test this hypothesis, we used error-prone PCR to introduce random point mutations into pcsB in vitro (Materials and Methods). After transformation of these mutated pcsB amplicons, we screened for temperature-sensitive (Ts) mutations that allowed colony growth at 32 °C but not 41.4 °C. Isolated Ts mutants contain amino acid changes in either the CC or CHAP domain of PcsB. In particular, one Ts mutant contains two amino acid changes (L78S L219P) in each of the predicted leucine zipper motifs in the CC domain of PcsB (Fig. 1). Constructed single mutants containing either the L78S or L219P change grew normally at 41.4 °C, indicating that the Ts phenotype requires both amino acid changes. The Ts phenotype caused by the pcsBL78S L219P mutations was fully complemented by expression of WT pcsB+ from an ectopic site, showing that the pcsBL78S L219P mutations are recessive. Importantly, the L78S L219P amino acid changes did not decrease the relative cellular amount of PcsB in pneumococcal cells grown at 32 °C or 41.4 °C (Fig. S6), arguing against a decrease in the stability of the mutant PcsBL78S L219P protein. Consistent with a loss of function, cells expressing PcsBL78S L219P showed mild or severe defects in cell morphology and division at 32 °C or 41.4 °C, respectively. (Fig. S7). At the nonpermissive temperature, the pcsBL78S L219P double mutant formed spherical cells that phenocopied the defect, causing severe depletion of PcsB or FtsX (Fig. 5). From these combined results, we conclude that the CC domain of PcsB is required for the function of this essential protein.

Discussion

Relatively little is known about the regulation of PG hydrolases that remodel the PG during cell division. Unlike autolysins produced by bacteriophages or during some stages of bacterial growth, the activity and location of remodeling PG hydrolases are likely to be tightly regulated and coordinated with the divisome. In the pathogenic ovococcus bacterium, S. pneumoniae, only four (PcsB, Pmp23 putative lytic transglycosylase, DacA dd-carboxypeptidase, or DacB ld-carboxypeptidase) of 11 proteins with predicted domains of PG hydrolases are required individually for normal cell division (12). Of these four proteins, only PcsB is essential for growth in serotype 2 strains (16, 18). PcsB has a two-domain structure characteristic of many extracellular Gram-positive PG hydrolases (Fig. 1) (13, 50). Besides a putative catalytic CHAP domain that could function as a PG amidase or endopeptidase (21–23, 27), PcsB contains an extended CC domain that could bind to another protein and attach PcsB to the cell surface. Its highly conserved amino acid sequence in different pneumococcal serotype strains has made PcsBSpn a leading candidate as a new vaccine target. Nevertheless, several purified constructs of PcsB have not exhibited PG hydrolase activity in different biochemical assays (12, 30).

This paradox of PcsB essentiality and lack of enzymatic activity led us to search for protein interactors in the pneumococcal cell membrane. We show here that cell-bound PcsB forms a complex with FtsEXSpn in the cell membrane (Figs. 2, 3, and 7 and Fig. S4). Binding experiments provided additional evidence for an interaction between the CC domain of PcsB and the large ECL1 domain of FtsXSpn (Fig. 4). Notably, the CC domain of PcsB is rich in hydrophobic leucine residues (Fig. 1), and PcsB is bound to the cell surface, partly by hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 2). A PcsB–FtsXSpn interaction was also supported by mislocalization of PcsB from the equators and septa of dividing cells on depletion of essential FtsXSpn (Figs. 5 and 6 and Fig. S3). Previously, bacterial two-hybrid assays suggested that PcsB might interact with DivIVASpn (49). An interaction was also reported between the PcsB homolog (GbpBSmu) of S. mutans and ribosomal proteins L7/L12Smu (33). However, it is difficult to reconcile direct binding between extracytoplasmic PcsB (Fig. 2) and cytoplasmic DivIVASpn or L7/L12Spn, unless these abundant cytoplasmic proteins are released into the culture medium from lysed cells. However, then, it is hard to see how release and rebinding of these cytoplasmic proteins would lead to an essential mechanism involving PcsB. We did not detect either of these interactions in this study, where the short formaldehyde cross-linker was used to stabilize protein complexes containing PcsB in membranes.

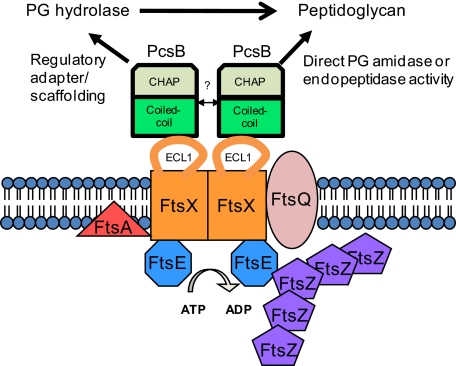

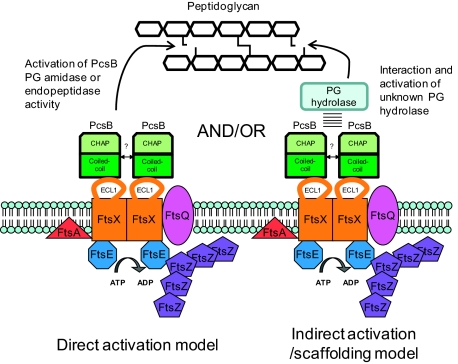

The interaction between PcsB and the FtsEXSpn complex suggests a possible explanation for the inactivity of purified PcsB. FtsE and FtsX homologs structurally resemble the cytoplasmic ATPase subunit and the membrane channel, respectively, of an ABC transporter (Fig. 8) (39, 40, 51). However, no extracellular transport receptor subunit has been associated with FtsEX, and mutations in the Walker box of FtsEEco impair constriction in E. coli cells (39). Consistent with a role in cell division, FtsEEco was shown to interact with FtsZEco (46), and FtsXEco bound to FtsQEco and FtsAEco (45). The binding of the CC domain of PcsB to the ECL1 of FtsXSpn may be required for PcsB PG hydrolase activity. In this model, the interaction of PcsB and FtsEXSpn would couple PG remodeling catalyzed by PcsB with Z-ring formation and cell division (Fig. 8). Consistent with this model, Ts mutations can be isolated in both the CC and CHAP domains of PcsB (Results and Materials and Methods). An initial attempt to stimulate a PG hydrolytic activity of purified PcsB by adding purified ECL1Spn was not successful. However, activation of a PcsB PG hydrolase activity may depend on additional interactions besides the binding of ECL1Spn to the PcsB CC domain, such as conformational changes induced by ATP hydrolysis by FtsESpn. Ongoing experiments will test these hypotheses.

Fig. 8.

Model for PcsB and FtsEXSpn interactions and functions in S. pneumoniae. In this model, a direct PG hydrolytic activity of PcsB is regulated by interactions that include binding of the CC domain of PcsB and the ECL1 of FtsXSpn. Membrane-bound FtsXSpn interacts with the cytoplasmic FtsESpn ATPase subunit. This model postulates that PG remodeling activity by PcsB is coordinated with cell division through its interaction with the FtsEXSpn complex, which interacts with FtsZSpn and other division proteins. Interaction of PcsB with the FtsEXSpn complex could also be required for PcsB to activate other PG hydrolases involved in cell division. Additional details in the text.

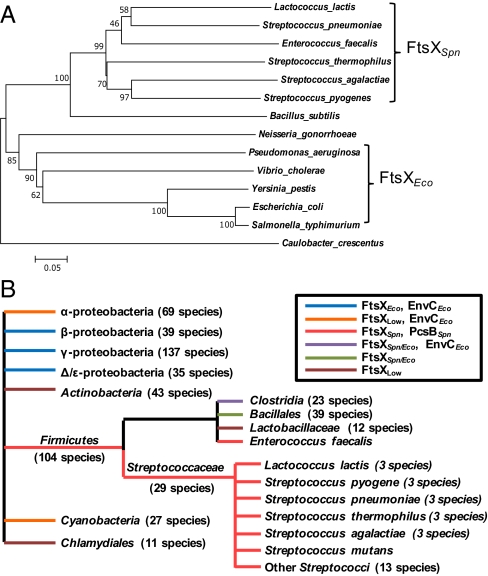

Support for a general role of FtsEX in controlling PG hydrolysis emerged concurrently in E. coli from the Bernhardt laboratory and is described in the accompanying paper by Yang et al. (52). In E. coli, the FtsEXEco complex interacts with the EnvCEco adapter protein, which in turn, is required for the enzymatic activity of the AmiA and AmiB amidases (53–55). Thus, the fundamental function of FtsEX in coupling PG remodeling to cell division may be conserved among widely disparate bacterial species, such as E. coli and S. pneumoniae, although the output enzymes controlled by this interaction (in this case, EnvCEco-AmiABEco or PcsBSpn) are different. Consistent with these parallel functions, bioinformatic analysis places FtsX from ovococcus species, such as S. pneumoniae, and enteric bacteria, such as E. coli, into distinct phylogenetic groups (Fig. 9A). Cooccurrence analysis also shows that strong homologs of EnvCEco and FtsXEco occur together in the β-, γ-, and Δ/ε-proteobacteria (Fig. 9B, dark blue lines), whereas the combination of FtsXSpn and PcsBSpn homologs occurs almost exclusively in Streptococcaceae and Enterococcus species (Fig. 9B, red lines).

Fig. 9.

Phylogenetic and cooccurrence analysis of FtsXSpn and FtsXEco. (A) Neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees of FtsX in different bacteria were generated as described in Materials and Methods. The percentages of replicate trees in bootstrap tests are shown next to branches in the tree. Results presented here show an interaction between PcsBSpn and FtsXSpn, and parallel findings show an interaction between FtsXEco and EnvCEco (52). Consistent with these different interactions, FtsXSpn and FtsXEco are in distinctly different branches of the FtsX phylogenetic tree. (B) Distribution and cooccurrence of FtsXSpn, FtsXEco, EnvCEco, and PcsBSpn were determined by string analysis as described in Materials and Methods and are diagrammatically represented, where branches indicate groups only and not evolutionary relatedness. FtsXSpn, FtsXEco, EnvCEco, and PcsBSpn indicate homologs in organisms with high (>100 bits) similarity to the corresponding pneumococcal or E. coli proteins. FtsXLow indicates FtsX homologs in organisms with low similarity scores (<100 bits) to either pneumococcal or E. coli FtsX. FtsXSpn/Eco indicates homologs in organisms with high similarity scores (>100 bits) to both FtsXSpn and FtsXEco. Cooccurrence of strong homologs to FtsXEco and EnvCEco occur throughout β-, γ-, and Δ/ε-proteobacteria, whereas cooccurrence of strong homologs of FtsXSpn and PcsBSpn are confined to the Streptococcaceae and Enterococcus faecalis. The Actinobacteria, Clamydiales, Bacillales, and Lactobacillaceae lack strong homologs of EnvCEco and PcsBSpn and presumably have other classes of proteins that interact with their FtsX homologs. Additional details are in the text.

In E. coli, the FtsEXEco interactor is the EnvCEco regulatory protein that lacks enzymatic activity, despite amino acid similarities to LytM PG hydrolases (54, 55). At this stage, we cannot rule out that PcsB acts as a regulatory protein for some other PG hydrolases, and this possibility is included in our current working model (Fig. 8). A role as an adaptor or scaffolding protein is not mutually exclusive with function as a PG hydrolase. Besides FtsXSpn (Fig. 3), we have not yet detected another interactor with PcsB, although these studies continue. If PcsB were acting as an adaptor, then deletion of genes encoding the PG hydrolases that interact with PcsB would result in lethal phenotypes for growth. To date, we have knocked out the spd_1874 gene, which encodes a putative N-acetyl muramidase (lysozyme), combined with nine other genes encoding established or putative PG hydrolases (Table S1) (12). None of these double mutations was lethal. Likewise, we constructed the triple mutant knocked out for all three of the genes (lytA (amidase) (56), cbpD (putative N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase or endopeptidase) (57), and lytC [N-acetyl muramidase (lysozyme)] (58)) that mediate growth-dependent autolysis and competence-induced fratricide. This set includes the only two other predicted amidases in S. pneumoniae. The triple mutant was not impaired for growth (59). Additional combinations of PG hydrolase mutations are being constructed and tested, but currently, there is no evidence for PcsB acting as an adapter, analogous to EnvCEco.

Unlike their homologs in E. coli and B. subtilis, FtsXSpn and FtsESpn are essential for growth, even in BHI broth containing 0.5% (wt/vol) NaCl, which rescues ftsEXEco mutants (40, 60). Strikingly, depletion of FtsXSpn or PcsB results in similar defects in chaining and cell division (Fig. 5) (16, 18). This phenocopying is consistent with a direct interaction between PcsB and FtsXSpn as well as mislocalization of PcsB on depletion of FtsXSpn (Figs. S3 and S5). The essentiality of FtsEXSpn matches the expectation that the membrane interactor of essential PcsB would itself be essential (shown in the Introduction). IFM indicates that PcsB localizes to the equators and septa of most dividing cells of an unencapsulated derivative of strain D39 (Fig. 6 and Fig. S3). We also observed lower amounts of PcsB at other sites in some cells, suggesting that PcsB localization may be dynamic and depend on stage of cell division. Septal localization was recently reported for the PcsB homolog (CdhASpy) of S. pyogenes (31). However, our results do not agree with the recent conclusion that PcsB is located at cell poles and is excluded from the septa of dividing cells (30). We clearly detect PcsB-l-FLAG3 at equators and septa in a pattern that matches regions of PG synthesis indicated by FL-V staining and FtsZSpn localization (Fig. S5, Left) (47–49), and we did not observe PcsB-l-FLAG3 at poles (Results, Fig. 6, and Fig. S3).

This discrepancy is not likely caused by using tagged PcsB. We did not detect any division defects in cells expressing carboxyl-terminal PcsB-l-FLAG3 from the native pcsB chromosomal locus (Figs. 1 and 6 and Fig. S3). In addition, moderate depletion of FtsXSpn mislocalized PcsB-l-FLAG3 but not FtsZSpn from midcells (Fig. S3). Given its essentiality in pneumococcus and its localization in E. coli (39, 40), it is highly likely that FtsXSpn interacts with the FtsZSpn divisome (Fig. 8). Moreover, IFM images in reference (30) do not include cell outlines, making it difficult to tell where staining occurred in cells and the stage of division. In fact, in some cells, PcsB seems to be located at the septa, and PcsB and FtsZSpn staining partially overlaps in some of the co-IFM images (30). We purposefully performed our IFM studies in unencapsulated derivatives of the prototypic serotype 2 strain D39, because capsule leads to chaining and masks or alters some morphological defects (12, 16). Although this other study was performed in an encapsulated serotype 4 strain (30), it is unclear whether the difference in genetic backgrounds or the presence of capsule would lead to a discrepancy in PcsB localization, if there is a discrepancy. IFM studies in progress will also examine whether PcsB localization is dynamic as a function of the cell cycle and will determine the localization of FtsXSpn and FtsESpn expressed from their native chromosomal locus.

Materials and Methods

SI Materials and Methods contains descriptions of the bacterial strains used, culture growth conditions, strain constructions, procedure used to deplete essential FtsXSpn, and fractionation of S. pneumoniae cells. It contains the protocols for formaldehyde cross-linking and pull down of PcsB complexes, purification of PcsB and its domains, ECL1Spn, and LytA protein used in Far Western blotting, and the reciprocal pull down of FtsESpn complexes. IFM protocols and bioinformatic analyses of phylogenetic and cooccurrence of FtsXSpn and PcsB and FtsXEco and EnvCEco are also described. Primers synthesized for this study are listed in Table S2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Bernhardt (Harvard Medical School) for sharing unpublished data about the interactions of FtsXEco and EnvCEco; Tiffany Tsui for unpublished strains; and Adrian Land, Dan Kearns, Kyle Wayne, Tiffany Tsui, and Krystyna Kazmierczak for comments about this work. S.M.B. was a predoctoral trainee with support from National Institute of Health Grant F31FM082090. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant 0543289 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R01AI060744 (to M.E.W.). Several mutants used in this study were constructed with support from National Institute of General Medical Science Grant R01GM085697 (Carol A. Gross, PI).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 18211.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1108323108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Henriques-Normark B, Normark S. Commensal pathogens, with a focus on Streptococcus pneumoniae, and interactions with the human host. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of pneumococcal pneumonia. Lancet. 2009;374:1543–1556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiser JN. The pneumococcus: Why a commensal misbehaves. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0557-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft EA. Antimicrobial resistance: It's not just for hospitals. JAMA. 2007;298:1803–1804. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black RE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: A systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janoff EN, Rubins JB. Invasive pneumococcal disease in the immunocompromised host. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:215–232. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapun A, Vernet T, Pinho MG. The different shapes of cocci. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:345–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Land AD, Winkler ME. The requirement for pneumococcal MreC and MreD is relieved by inactivation of the gene encoding PBP1a. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4166–4179. doi: 10.1128/JB.05245-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young KD. Bacterial shape: Two-dimensional questions and possibilities. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:223–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pérez-Núñez D, et al. A new morphogenesis pathway in bacteria: Unbalanced activity of cell wall synthesis machineries leads to coccus-to-rod transition and filamentation in ovococci. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:759–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zapun A, Contreras-Martel C, Vernet T. Penicillin-binding proteins and beta-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:361–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barendt SM, Sham LT, Winkler ME. Characterization of mutants deficient in the L,D-carboxypeptidase (DacB) and WalRK (VicRK) regulon, involved in peptidoglycan maturation of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 2 strain D39. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2290–2300. doi: 10.1128/JB.01555-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:259–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eldholm V, et al. Pneumococcal CbpD is a murein hydrolase that requires a dual cell envelope binding specificity to kill target cells during fratricide. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:905–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Håvarstein LS, Martin B, Johnsborg O, Granadel C, Claverys JP. New insights into the pneumococcal fratricide: Relationship to clumping and identification of a novel immunity factor. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1297–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barendt SM, et al. Influences of capsule on cell shape and chain formation of wild-type and pcsB mutants of serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3024–3040. doi: 10.1128/JB.01505-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giefing C, et al. Discovery of a novel class of highly conserved vaccine antigens using genomic scale antigenic fingerprinting of pneumococcus with human antibodies. J Exp Med. 2008;205:117–131. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng WL, Kazmierczak KM, Winkler ME. Defective cell wall synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 depleted for the essential PcsB putative murein hydrolase or the VicR (YycF) response regulator. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1161–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng WL, et al. Constitutive expression of PcsB suppresses the requirement for the essential VicR (YycF) response regulator in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1647–1663. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkler ME, Hoch JA. Essentiality, bypass, and targeting of the YycFG (VicRK) two-component regulatory system in gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2645–2648. doi: 10.1128/JB.01682-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anantharaman V, Aravind L. Evolutionary history, structural features and biochemical diversity of the NlpC/P60 superfamily of enzymes. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-r11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bateman A, Rawlings ND. The CHAP domain: A large family of amidases including GSP amidase and peptidoglycan hydrolases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:234–237. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layec S, Decaris B, Leblond-Bourget N. Characterization of proteins belonging to the CHAP-related superfamily within the Firmicutes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;14:31–40. doi: 10.1159/000106080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokoi KJ, et al. The two-component cell lysis genes holWMY and lysWMY of the Staphylococcus warneri M phage varphiWMY: Cloning, sequencing, expression, and mutational analysis in Escherichia coli. Gene. 2005;351:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pritchard DG, Dong S, Baker JR, Engler JA. The bifunctional peptidoglycan lysin of Streptococcus agalactiae bacteriophage B30. Microbiology. 2004;150:2079–2087. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rashel M, et al. Tail-associated structural protein gp61 of Staphylococcus aureus phage phi MR11 has bifunctional lytic activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;284:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Layec S, et al. The CHAP domain of Cse functions as an endopeptidase that acts at mature septa to promote Streptococcus thermophilus cell separation. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1205–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajimura J, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of an N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidase Sle1 involved in cell separation of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:1087–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stentz R, et al. CsiA is a bacterial cell wall synthesis inhibitor contributing to DNA translocation through the cell envelope. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:779–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giefing-Kröll C, Jelencsics KE, Reipert S, Nagy E. Absence of pneumococcal PcsB is associated with overexpression of LysM domain-containing proteins. Microbiology. 2011;157:1897–1909. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.045211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pancholi V, Boël G, Jin H. Streptococcus pyogenes Ser/Thr kinase-regulated cell wall hydrolase is a cell division plane-recognizing and chain-forming virulence factor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30861–30874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills MF, Marquart ME, McDaniel LS. Localization of PcsB of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its differential expression in response to stress. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4544–4546. doi: 10.1128/JB.01831-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattos-Graner RO, Porter KA, Smith DJ, Hosogi Y, Duncan MJ. Functional analysis of glucan binding protein B from Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3813–3825. doi: 10.1128/JB.01845-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reinscheid DJ, Gottschalk B, Schubert A, Eikmanns BJ, Chhatwal GS. Identification and molecular analysis of PcsB, a protein required for cell wall separation of group B streptococcus. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1175–1183. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1175-1183.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wayne KJ, et al. Localization and cellular amounts of the WalRKJ (VicRKX) two-component regulatory system proteins in serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:4388–4394. doi: 10.1128/JB.00578-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinscheid DJ, Ehlert K, Chhatwal GS, Eikmanns BJ. Functional analysis of a PcsB-deficient mutant of group B streptococcus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;221:73–79. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price KE, Camilli A. Pneumolysin localizes to the cell wall of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:2163–2168. doi: 10.1128/JB.01489-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao G, Meier TI, Peery RB, Matsushima P, Skatrud PL. Biochemical and molecular analyses of the C-terminal domain of Era GTPase from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology. 1999;145:791–800. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-4-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arends SJ, Kustusch RJ, Weiss DS. ATP-binding site lesions in FtsE impair cell division. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3772–3784. doi: 10.1128/JB.00179-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt KL, et al. A predicted ABC transporter, FtsEX, is needed for cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:785–793. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.785-793.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Leeuw E, et al. Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli FtsE and FtsX. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:983–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos-Montañez S, Kazmierczak KM, Hentchel KL, Winkler ME. Instability of ackA (acetate kinase) mutations and their effects on acetyl phosphate and ATP amounts in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6390–6400. doi: 10.1128/JB.00995-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Opijnen T, Bodi KL, Camilli A. Tn-seq: High-throughput parallel sequencing for fitness and genetic interaction studies in microorganisms. Nat Methods. 2009;6:767–772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimova G, Dautin N, Ladant D. Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2233–2243. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2233-2243.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corbin BD, Wang Y, Beuria TK, Margolin W. Interaction between cell division proteins FtsE and FtsZ. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3026–3035. doi: 10.1128/JB.01581-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morlot C, Noirclerc-Savoye M, Zapun A, Dideberg O, Vernet T. The D,D-carboxypeptidase PBP3 organizes the division process of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:1641–1648. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morlot C, Zapun A, Dideberg O, Vernet T. Growth and division of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Localization of the high molecular weight penicillin-binding proteins during the cell cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:845–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fadda D, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae DivIVA: Localization and interactions in a MinCD-free context. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:1288–1298. doi: 10.1128/JB.01168-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fischetti VA. Bacteriophage lysins as effective antibacterials. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss DS. Bacterial cell division and the septal ring. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:588–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang DC, et al. ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-like complex governs cell-wall hydrolysis at the bacterial cytokinetic ring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:E1052–E1060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107780108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. Screening for synthetic lethal mutants in Escherichia coli and identification of EnvC (YibP) as a periplasmic septal ring factor with murein hydrolase activity. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1255–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uehara T, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. LytM-domain factors are required for daughter cell separation and rapid ampicillin-induced lysis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5094–5107. doi: 10.1128/JB.00505-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uehara T, Parzych KR, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J. 2010;29:1412–1422. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tomasz A, Moreillon P, Pozzi G. Insertional inactivation of the major autolysin gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5931–5934. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5931-5934.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kausmally L, Johnsborg O, Lunde M, Knutsen E, Håvarstein LS. Choline-binding protein D (CbpD) in Streptococcus pneumoniae is essential for competence-induced cell lysis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4338–4345. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4338-4345.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García P, Paz González M, García E, García JL, López R. The molecular characterization of the first autolytic lysozyme of Streptococcus pneumoniae reveals evolutionary mobile domains. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:128–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eldholm V, Johnsborg O, Haugen K, Ohnstad HS, Håvarstein LS. Fratricide in Streptococcus pneumoniae: Contributions and role of the cell wall hydrolases CbpD, LytA and LytC. Microbiology. 2009;155:2223–2234. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.026328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy M. Role of FtsEX in cell division of Escherichia coli: Viability of ftsEX mutants is dependent on functional SufI or high osmotic strength. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:98–108. doi: 10.1128/JB.01347-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]