Abstract

Cardiac atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) regulates arterial blood pressure, moderates cardiomyocyte growth, and stimulates angiogenesis and metabolism. ANP binds to the transmembrane guanylyl cyclase (GC) receptor, GC-A, to exert its diverse functions. This process involves a cGMP-dependent signaling pathway preventing pathological [Ca2+]i increases in myocytes. In chronic cardiac hypertrophy, however, ANP levels are markedly increased and GC-A/cGMP responses to ANP are blunted due to receptor desensitization. Here we show that, in this situation, ANP binding to GC-A stimulates a unique cGMP-independent signaling pathway in cardiac myocytes, resulting in pathologically elevated intracellular Ca2+ levels. This pathway involves the activation of Ca2+‐permeable transient receptor potential canonical 3/6 (TRPC3/C6) cation channels by GC-A, which forms a stable complex with TRPC3/C6 channels. Our results indicate that the resulting cation influx activates voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels and ultimately increases myocyte Ca2+i levels. These observations reveal a dual role of the ANP/GC-A–signaling pathway in the regulation of cardiac myocyte Ca2+i homeostasis. Under physiological conditions, activation of a cGMP-dependent pathway moderates the Ca2+i-enhancing action of hypertrophic factors such as angiotensin II. By contrast, a cGMP-independent pathway predominates under pathophysiological conditions when GC-A is desensitized by high ANP levels. The concomitant rise in [Ca2+]i might increase the propensity to cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmias.

Guanylyl cyclase A (GC-A, also known as natriuretic peptide receptor A) synthesizes the second messenger cGMP upon binding of the cardiac hormones atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) (1). The natriuretic peptide (NP)/GC-A/cGMP system has critical functions in the maintenance of arterial blood pressure and local actions preventing pathological cardiac hypertrophy (2). In particular, ANP, via GC-A and cGMP, counteracts the Ca2+i-dependent hypertrophic actions of angiotensin II (Ang II) (2, 3). One downstream target activated by ANP/cGMP in myocytes is cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (PKG I). PKG I inhibits Ang II/AT1-mediated Ca2+ influx into myocytes through activation of regulator of G-protein signaling 2 and via inhibition of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC3/C6) channels (3–6).

The GC-A receptor consists of an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a short membrane-spanning region, and an intracellular part containing a kinase homology (KH) domain, a coiled-coil dimerization domain, and the C-terminal catalytic GC region (7). In absence of ligand, the KH domain is highly phosphorylated and the catalytic activity of GC-A is repressed (7). Upon ANP binding, a conformational change occurs that activates the cyclase domain (8). Presumably, all effects of ANP/GC-A are mediated by the synthesis of cGMP (1, 7).

ANP and BNP levels are markedly increased in patients with hypertensive cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (1, 9). However, GC-A–mediated cGMP formation and endocrine effects of NPs are blunted, indicating desensitization of the receptor (1). NP-induced homologous desensitization of GC-A is due to posttranslational modifications, particularly to dephosphorylation within the KH domain (10, 11). Internalization and degradation of GC-A seem to play no major role (12). However, it is unknown how this impairment of the cyclase activity of GC-A affects the cardiac actions of ANP. Hence, here we investigated whether GC-A desensitization alters the effect of ANP on myocyte Ca2+ handling and growth.

Our observations demonstrate a dual function of GC-A in the regulation of myocyte Ca2+i homeostasis. Under baseline conditions, ANP, via GC-A and cGMP/PKG I signaling, prevents Ca2+i-stimulating effects of Ang II. By contrast, ANP increases myocyte L-type Ca2+-channel (LTCC) currents and [Ca2+]i when the receptor is desensitized during cardiac hypertrophy, or if cGMP/PKG I signaling is impaired. This cGMP-independent signaling pathway of ANP/GC-A is initiated by the activation of TRPC3/C6 channels within a preexisting stable GC-A/TRPC protein complex. Our findings provide a general mechanism for GC-A to modulate cellular responses through elevating Ca2+i levels in a cGMP-independent fashion.

Results

Cardiac Hypertrophy Is Accompanied by Altered Myocyte cGMP and Ca2+ Responses to ANP.

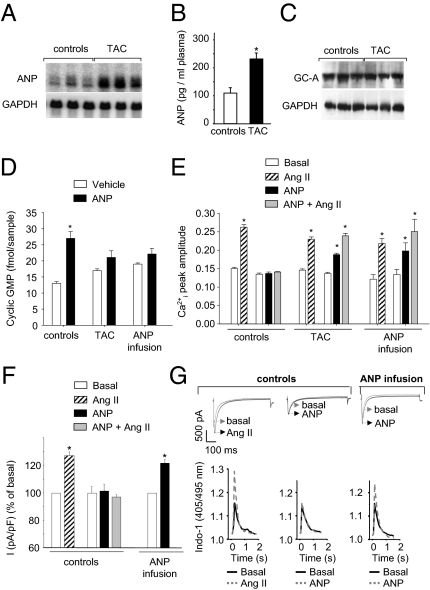

To study whether desensitization of the GC-A receptor alters cardiac signaling by ANP, we induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice by surgical transverse aortic constriction (TAC). Mice with TAC and sham controls were euthanized after 4 d for determination of ANP and GC-A expression and for isolation of ventricular myocytes. These myocytes were used to study the cGMP and Ca2+ responses to synthetic ANP and Ang II. TAC increased the heart-weight-to-body-weight ratio by 46 ± 4%. This cardiac enlargement was accompanied by increased myocyte ANP mRNA (by ∼5.1-fold) and plasma ANP levels (by ∼2.1-fold) (Fig. 1 A and B). Lung GC-A protein levels were unaltered (Fig. 1C). Presumably levels of GC-A in myocytes were also unaltered after TAC, although here expression is too low for detection by Western blotting (2). In control myocytes, incubation with synthetic ANP (100 nM, 10 min) increased cGMP contents (Fig. 1D). In contrast, ANP had no effect on cGMP content of myocytes from mice with TAC, indicating GC-A desensitization (Fig. 1D). Fluorescent imaging of Ca2+i transients in Indo-1 AM loaded, electrically paced (0.5 Hz) single myocytes showed that Ang II (10 nM) acutely amplified Ca2+i transients in myocytes from control and TAC mice (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1). In controls, ANP (100 nM, 10 min) had no direct effect on basal Ca2+i transients but prevented their stimulation by Ang II. Surprisingly, in myocytes from mice with TAC, ANP itself acutely amplified Ca2+i transients and failed to prevent their stimulation by Ang II (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Cardiac hypertrophy after transverse aortic constriction (TAC) is accompanied by altered myocyte cGMP and Ca2+ responses to ANP. (A) Northern blot showing cardiac expression of ANP and GAPDH. (B) Plasma levels of immunoreactive ANP (*P < 0.05 vs. controls). (C) Western blots showing levels of GC-A and GAPDH in lungs. (D) Effect of synthetic ANP (100 nM, 10 min) on cGMP contents of freshly isolated myocytes (*P < 0.05 vs. vehicle). (E and F) Peak amplitudes of Ca2+i transients [Indo-1 ratio405/495nm, systolic–diastolic (E)] and LTCC current densities [I (pA/pF), in percent (F)] at baseline and after application of Ang II, ANP, or ANP and Ang II (n = 6\x{2013}8; *P < 0.05 vs. basal). (G) LTCC current (Upper) and Ca2+i-transient traces (Lower) of three cells (from control vs. ANP-infused mice) at baseline and during superfusion with Ang II or ANP.

To verify that the altered myocyte cGMP and Ca2+ responses to ANP were related to the chronically increased levels of endogenous ANP, mice were infused with synthetic ANP (1.5 μg/kg BW/min) for 4 d using osmotic minipumps. Thereafter, myocytes were isolated to study the acute cGMP and Ca2+ responses to ANP. In addition to fluorometric Ca2+i recordings, Ca2+ currents (ICa) through LTCC were measured using the patch-clamp technique in the whole-cell configuration. Fig. 1D shows that ANP did not enhance cGMP contents of myocytes isolated from mice infused with ANP, indicating GC-A desensitization. In myocytes from control mice, Ang II (10 nM) increased ICa (Fig. 1 F and G). ANP (100 nM, 10 min) had no effect on basal ICa, but fully prevented the stimulation by Ang II (Fig. 1 F and G). Notably, in myocytes from ANP-infused mice, ANP itself stimulated ICa and Ca2+i transients and did not prevent the effects of Ang II (Fig. 1 E–G and Fig. S1).

ANP, via GC-A, Increases Myocyte Ca2+i When cGMP/PKG I Signaling Is Inhibited.

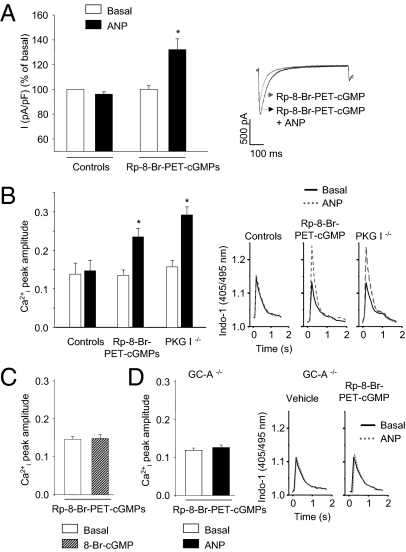

Next we investigated whether the effect of GC-A desensitization on ANP/calcium signaling can be mimicked by inhibition of PKG I. Superfusion of myocytes with the PKG I inhibitor Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPs (10 μM, 15 min) did not alter baseline ICa and Ca2+i transients (Fig. 2 A and B). Subsequent addition of 100 nM ANP acutely enhanced ICa and Ca2+i transients (Fig. 2 A and B). To corroborate the specificity of this observation, we used a genetic mouse model that lacks expression of PKG I in myocytes (13). As shown in Fig. 2B, basal Ca2+i transients were in PKG I−/− myocytes as in respective controls and increased upon addition of ANP. This stimulatory effect was not mimicked by the cGMP analog, 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM, 15 min) (Fig. 2C). Of note, GC-A−/− myocytes with inhibited PKG I were refractory to the Ca2+i-stimulating effect of ANP (Fig. 2D). Thus, inhibition of GC-A/cGMP or cGMP/PKG I signaling reveals a direct stimulatory effect of ANP on LTCC currents and Ca2+i transients. This effect is mediated by the GC-A receptor but not by cGMP.

Fig. 2.

ANP, via GC-A signaling, increases LTCC currents and Ca2+i transients in myocytes with inhibited PKG I. Effect of ANP on LTCC current densities [I (pA/pF), in percent (A)] and Ca2+i transients (B) in untreated myocytes (controls), myocytes pretreated with the PKG I inhibitor Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPs, and in PKG I-deficient (PKG I−/−) myocytes. The stimulatory effect of ANP on Ca2+i transients was not mimicked by 8-Br-cGMP, (C) and it was abolished in GC-A–deficient (GC-A−/−) myocytes (D). n = 6–8; *P < 0.05 vs. basal. Right panels in A, B, and D are examples of original tracings.

TRPC3/C6 Channels Are Involved in the Stimulatory Effect of ANP on Myocyte Ca2+ Levels.

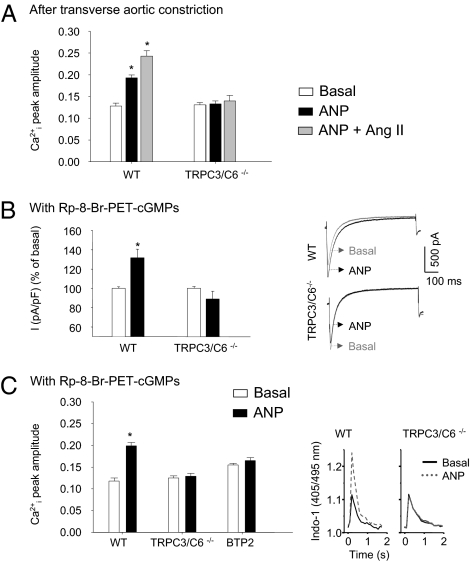

TRPC3 and TRPC6 channels mediate the stimulatory effects of Ang II on myocyte Ca2+ influx (14). PKG I-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of the channels underlies prevention of pathological Ca2+i increases by NP/GC-A/cGMP (4–6). To elucidate whether stimulatory Ca2+ effects of ANP accompanying GC-A desensitization also involve TRPC3/C6 channels, we studied myocytes from double-KO mice with genetic deletion of both proteins (TRPC3−/−/C6−/−) (3). To induce GC-A desensitization, TRPC3−/−/C6−/− and WT mice were subjected to TAC for 4 d. Thereafter, myocytes were isolated for fluorometric Ca2+i recordings. Basal Ca2+i transients of WT and TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes were similar (Fig. 3A and Table S1). In myocytes from WT mice with TAC, ANP once more acutely enhanced Ca2+i transients and failed to prevent stimulatory effects of Ang II. The effects of ANP and Ang II were abolished in TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the responses to β-adrenergic stimulation [by 10 nM isoproterenol (ISO), which was used as control] were not different between genotypes (Table S1).

Fig. 3.

TRPC3/C6 channels mediate the Ca2+-stimulating effects of ANP in myocytes with inhibited cGMP/PKG I signaling. (A) Myocytes isolated from mice after TAC. Shown are peak amplitudes of Ca2+i transients at baseline and after application of ANP or ANP and Ang II in WT and TRPC3/C6−/− myocytes. (B and C) Myocytes pretreated with the PKG I inhibitor Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPs. The effect of ANP on LTCC current densities [I (pA/pF), in percent (B)] and Ca2+i transients (C) of WT or TRPC3/C6−/− myocytes is shown. In addition, the effect of the TRPC channel inhibitor BTP2 on Ca2+i transients was tested (C). n = 6; *P < 0.05 vs. basal. Right panels in B and C are examples of original tracings.

Next we combined electrophysiology and fluorometric Ca2+i recordings to analyze the effect of the PKG I inhibitor Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPs (100 μM, 15 min) on responses of WT and TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes to ANP. Basal ICa and Ca2+i transients of WT and TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes were similar (Fig. 3 B and C). Ca2+-current densities amounted to −6.16 ± 0.59 pA/pF in WT and to −6.23 ± 0.54 pA/pF in TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes. In WT, inhibition of PKG I again revealed stimulatory effects of ANP on ICa and Ca2+i transients (Fig. 3 B and C). These effects of ANP were absent in TRPC3−/−/C6−/− myocytes. Also, pretreatment of WT myocytes with the TRPC channel inhibitor BTP2 [2 μM, 5 min (15)], prevented the stimulatory effects of ANP on Ca2+i transients (Fig. 3C). In contrast, ISO stimulation of ICa and Ca2+i transients was not different between genotypes and was not altered by Rp-8-Br-PET-cGMPs and/or by BTP2 (Table S1). We conclude that TRPC3/C6 channels are involved in the Ca2+-stimulating effect of ANP, which is revealed when GC-A/cGMP/PKG I signaling is impaired.

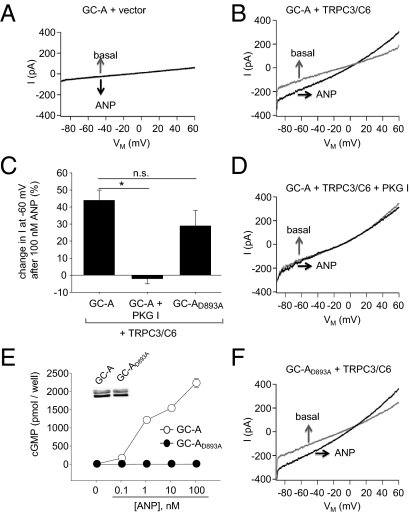

To further investigate ANP/GC-A activation of TRPC3/C6 channels in the absence of PKG I, whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed on HEK293 cells, lacking endogenous PKG I (16). TRPC3/C6 channel activity was measured by voltage ramps from −90 to +60 mV over 250 ms from a holding potential of −70 mV (17). Currents were recorded first under superfusion with bath solution (basal) and thereafter under superfusion with 100 nM ANP. In HEK cotransfected with GC-A and vector, baseline current densities amounted to −4.32 ± 0.5 pA/pF and were not altered by ANP (Fig. 4A). In HEK cotransfected with GC-A and TRPC3/C6, baseline current densities were significantly larger (−14.64 ± 3.04 pA/pF; P < 0.05 vs. vector). At a membrane potential of −60 mV, ANP stimulated the TRPC3/C6-mediated cation inward current by 44 ± 6% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4 B and C). This effect of ANP was abolished in HEK additionally cotransfected with PKG I (Fig. 4 C and D). To follow the hypothesis that ANP/GC-A stimulation of TRPC3/C6 channel activity is cGMP independent, we coexpressed TRPC3/C6 channels with the mutated receptor GC-AD893A. This point mutation disrupts cyclase activity while preserving ANP binding (18). cGMP measurements confirmed the inactivation of GC activity: HEK transfected with WT GC-A responded to ANP with typical elevations of cGMP (by ∼3,024-fold at 100 nM ANP) (Fig. 4E). This response was almost abolished in HEK293 cells transfected with GC-AD893A (∼6-fold increases in cGMP at 100 nM ANP), despite unaltered receptor expression levels (Fig. 4E). Notably, the stimulatory effect of ANP/GC-AD893A on TRPC3/C6 activity was preserved (Fig. 4 C and F).

Fig. 4.

ANP/GC-A stimulates TRPC3/C6 channel activity in transfected HEK293 cells. Shown are cation currents in HEK coexpressing GC-A and either vector [(A) n = 5] or TRPC3/C6 (B–D) or TRPC3/C6 and PKG I (C and D) (all n = 10–13) and HEK coexpressing GC-AD893A and TRPC3/C6 (D and F) (n = 7). Cells additionally expressed EGFP and were identified by their marked fluorescence. Currents were recorded first under superfusion with bath solution (basal) and afterward during addition of 100 nM ANP. (A, B, D, and F) Current amplitudes in relation to membrane potential of representative cells and mean percentage of changes in response to ANP (C) (*P < 0.05). (E) Effects of ANP on cGMP levels in HEK expressing WT GC-A or GC-AD893A (n = 8). (Inset) Western blotting of GC-A and GC-AD893A membrane expression levels (all 10 μg protein per lane).

Association of GC-A and TRPC3/C6 Proteins in HEK293 Cells and in Cardiac Myocytes.

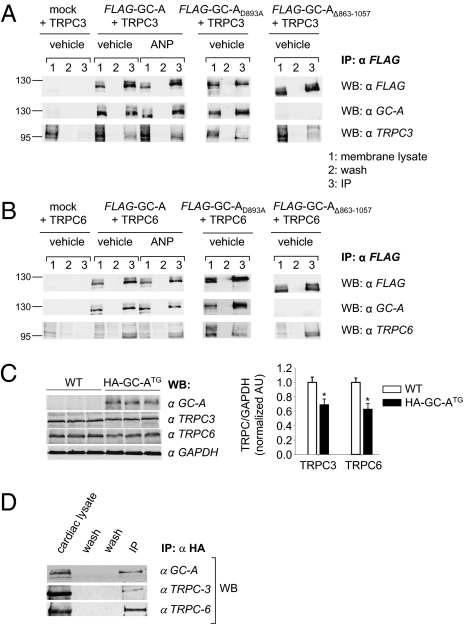

The N and C termini of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels bind select proteins that regulate channel trafficking and gating (19). Hence, we examined the possibility that the modulation of TRPC3/C6 channel activity by GC-A involves a direct protein interaction. TRPC3 or TRPC6 were transiently coexpressed in HEK together with FLAG-tagged GC-A (11). The membrane fraction of transfected cells was used to enrich GC-A by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG (M2) antibody coupled to agarose beads. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS-sample buffer. Western blotting with antibodies against FLAG, against the C terminus of GC-A (11), and against either TRPC3 or TRPC6 demonstrated coimmunoprecipitation of TRPC3 or TRPC6 with GC-A (Fig. 5 A and B). Fig. 5 also shows that ANP (100 nM, 10 min) did not change the association of GC-A with TRPC proteins.

Fig. 5.

Stable association of GC-A and TRPC3 or TRPC6 in HEK293 cells and native myocytes. Coimmunoprecipitation of TRPC3 (A) or TRPC6 (B) with FLAG-GC-A, FLAG-GC-AD893A, or FLAG-GC-AΔ863–1057 from membranes of cotransfected HEK. Membrane fractions and immunoprecipitates (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody were separated on 10% SDS/PAGE and blotted with antibodies against FLAG, GC-A, TRPC3, or TRPC6. Incubation of HEK cells with ANP did not change the amount of coimmunoprecipitated FLAG-GC-A-TRPC proteins. The molecular weight in kilodaltons is shown at the left of the blot. (C) Western blot demonstrates cardiac overexpression of HA-tagged GC-A in transgenic compared with WT mice. Levels of TRPC3 and TRPC6 were slightly diminished in the transgenics (n = 3; *P < 0.05 vs. WT). (D) Heart lysates from HA-GC-ATG mice were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody. The immunoblots with antibodies against GC-A, TRPC3, or TRPC6 showed coimmunoprecipitation of both TRPC3 and TRPC6 protein with HA-GC-A. All are representative Western blots of three independent experiments. Inputs were 1/10–1/20 of the protein used for IP. Control IPs using IgG do not give similar reactions.

To further investigate the hypothesis that GC-A and TRPC interaction mediates cGMP-independent effects of ANP, we coexpressed TRPC3 or -C6 either with the cyclase inactive mutant FLAG-tagged GC-AD893A or with a truncated receptor lacking the GC domain (FLAG-tagged GC-AΔ863–1057). The coimmunoprecipitation experiments again demonstrated a significant association (Fig. 5 A and B). Thus, inactivation or deletion of the catalytic domain has no influence on the interaction of GC-A with TRPC3 and TRPC6.

To address the specificity of this interaction, we coexpressed in HEK cells in FLAG-GC-A with two other members of the TRPC family, TRPC4 and TRPC5. Western blot with antibodies against FLAG and against TRPC4 or TRPC5 demonstrated the membrane expression of GC-A and either TRPC channel (Fig. S2). However, the coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated no significant association (Fig. S2).

To verify that the interaction of GC-A and TRPC3/C6 occurs also in myocytes, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with cardiac protein lysates. As already mentioned, myocyte GC-A expression is very low and not detectable by Western blotting (Fig. 5C). Therefore, we used transgenic mice with αMHC-driven myocyte overexpression of HA-tagged GC-A (Fig. 5C). Notably, cardiac expression of both TRPC3 and TRPC6 was slightly diminished in the transgenics (Fig. 5C). HA-tagged GC-A was immunoprecipitated by anti-HA antibody coupled to agarose beads. Immunoblot analyses showed coprecipitation of both TRPC3 and TRPC6 (Fig. 5D), indicating that endogenous TRPC3 and -C6 actually bind to GC-A in myocytes.

Single-Cell FRET Analysis Demonstrates That ANP Modulates the Interaction Between GC-A and TRPC3 in HEK293 Cells.

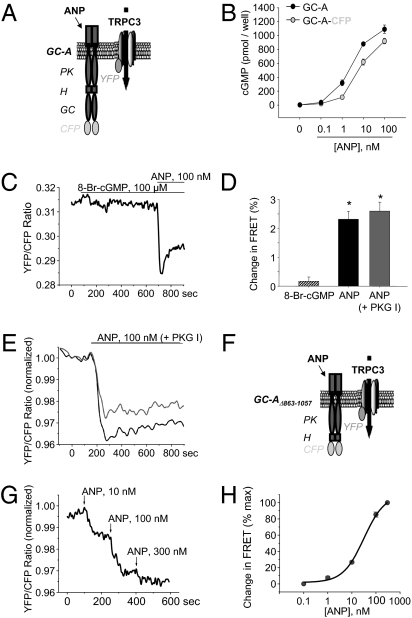

FRET microscopy highlights in vivo protein–protein interactions. To analyze the FRET signal between GC-A and TRPC3, cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) was fused to the C terminus of GC-A (Fig. 6A). We confirmed unaltered cGMP responses of GC-A-CFP to ANP (Fig. 6B). Coexpression of GC-A-CFP and TRPC3-YFP (20) resulted in substantial basal FRET (Fig. 6C), suggesting close proximity between their C termini. This signal was insensitive to 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM, 10 min) (Fig. 6 C and D). In contrast, ANP (100 nM) induced very rapid, significant decreases in FRET by 2–3% within 10.3 ± 1.4 s (Fig. 6 C and D), indicative of an agonist-induced rearrangement within the GC-A–TRPC3 complex. Notably, these responses were not altered by coexpression of PKG I (Fig. 6 D and E). Thus, ANP modulates the interaction between GC-A and TRPC3 independently of cGMP/PKG I. To follow up on this hypothesis, we used the GC-truncated mutant protein GC-AΔ863–1057 fused to CFP (Fig. 6F). Fig. 6 G and H shows that coexpression of GC-AΔ863–1057-CFP and TRPC3-YFP produced a FRET signal, which was reduced by ANP in a concentration-dependent manner (EC50 ∼30 nM). These data corroborate that GC-A and TRPC interact with each other. ANP binding to GC-A induces a conformational rearrangement in the GC-A/TRPC protein complex, which possibly directly stimulates TRPC3/C6 channel activity when GC-A/cGMP/PKG I signaling is inhibited.

Fig. 6.

FRET reveals the rapid ANP-modulated rearrangement of the GC-A–TRPC3 complex in cotransfected HEK293 cells. (A and F) Schemes of C-terminal CFP-labeled GC-A or GC-AΔ863–1057 and TRPC3-YFP. (B) Effects of ANP on cGMP levels in HEK expressing GC-A or GC-A-CFP. (C) Representative ratiometric recording of single-cell FRET signals in HEK cotransfected with GC-A-CFP and TRPC3-YFP at baseline and during superfusion of 8-Br-cGMP and ANP. (D) Relative FRET changes (n = 12; *P < 0.05 vs. baseline). (E) Effects of ANP on FRET between GC-A-CFP and TRPC3-YFP in HEK additionally cotransfected with PKG I (n = 6). (G) Representative ratiometric recordings of single-cell FRET signals in HEK cotransfected with GC-AΔ863–1057-CFP and TRPC3-YFP at baseline and during superfusion with ANP. (H) Concentration-dependent effects of ANP on FRET between GC-AΔ863–1057-CFP and TRPC3-YFP (EC50 ∼30 nM; n = 11).

Homologous Desensitization of GC-A Does Not Alter the Modulation of the GC-A–TRPC Complex by ANP.

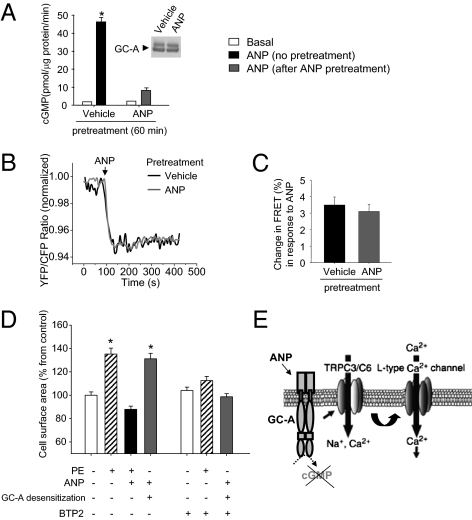

Next we investigated in HEK293 cells how ANP-induced homologous desensitization of the GC-A receptor affects the GC-A–TRPC complex and its modulation by ANP. For GC-A desensitization, transfected HEK cells were treated with ANP (100 nM) for 60 min (10–12). Western blot demonstrated unaltered membrane expression of GC-A under these conditions (Fig. 7A). The effect of ANP pretreatment on GC-A/cGMP activity was evaluated in guanylyl cyclase assays performed with crude membranes. Whereas membranes from vehicle-treated HEK cells showed efficient cGMP production in response to ANP (100 nM, acute 5-min stimulation), this response was severely blunted in membranes prepared from ANP-pretreated cells (Fig. 7A). We then used FRET to study the effect of the GC-A desensitization on GC-A-CFP–TRPC3-YFP interactions. As shown in Fig. 7B, the basal FRET signal from untreated and respective ANP-pretreated cells was similar. Moreover, ANP (100 nM) evoked similar rapid decreases in FRET in control cells (by 3.5 ± 0.49% within 10.1 ± 1.2 s) and in ANP-pretreated, desensitized cells (by 3.0 ± 0.47% within 10.8 ± 1.4 s) (Fig. 7 B and C), further corroborating that ANP modulation of GC-A–TRPC interaction is independent of the GC-A cGMP-forming activity.

Fig. 7.

Homologous desensitization of GC-A impairs guanylyl cyclase activity but preserves the effect of ANP on rearrangement of the GC-A–TRPC3 complex, revealing prohypertrophic actions of the hormone. (A) GC-A expressing HEK293 cells were pretreated with vehicle or ANP (100 nM, 60 min) before preparation of crude cell membranes for determination of basal (vehicle) vs. acute ANP-stimulated cGMP formation (n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. basal). (Inset) Western blotting of GC-A expression levels in vehicle vs. ANP-pretreated cells (all 10 μg protein per lane). (B) Recordings of single-cell FRET signals in HEK cotransfected with GC-A-CFP and TRPC3-YFP at baseline and in response to acute addition of ANP. (C) Relative FRET changes evoked by ANP in vehicle- or ANP-pretreated cells (n = 11). (D) Cell surface area of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes treated with phenylephrine (PE, 100 μM, 48 h) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of ANP (100 nM, 48 h) or with ANP (100 nM, 48 h) after GC-A desensitization (100 nM ANP, 60 min of pretreatment). Effect of BTP2 (2 μM, 15 min pretreatment) on growth responses to PE and ANP (n = 3; 100 cells per experiment). (E) Schematic model showing how GC-A associates with TRPC3/C6 channels to form a stable complex in myocytes. When cGMP formation by GC-A is blunted, ANP via GC-A directly activates TRPC3 and TRPC6 (TRPC3/C6) channels. Subsequent cation influx ultimately activates LTCC currents.

Homologous Desensitization of GC-A Induces Hypertrophic Effects of ANP in Cardiomyocytes.

Finally, we examined in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes whether desensitization of GC-A alters the growth responses to ANP. Treatment with phenylephrine (100 μM, 48 h) significantly enlarged myocyte surface area, and this effect was supressed by simultaneous treatment with ANP (100 nM) (Fig. 7D). This is concordant with published studies showing that ANP, via GC-A/cGMP/PKGI signaling, counteracts hypertrophic responses to Gαq-coupled receptors (2–6). For GC-A desensitization, myocytes were first pretreated with ANP (100 nM) for 60 min (as above). As shown in Fig. 7D, subsequent restimulation of myocytes with ANP (100 nM, 48 h) induced significant hypertrophy. The hypertrophic effects of phenylephrine and ANP were almost completely blocked in the presence of BTP2 (2 μM), indicating the involvement of TRPC3/C6 channels (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that the GC-A–TRPC3/C6-signaling pathway described here mediates hypertrophic responses of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes to ANP when GC-A is desensitized and cGMP formation is impaired.

Discussion

We have uncovered a unique signaling pathway involving a complex between a receptor guanylyl cyclase (GC-A) and TRPC3/C6 channels. This pathway mediates cGMP-independent myocyte Ca2+i responses to ANP activation of GC-A. Together with previous studies (3–6), our data demonstrate that cGMP, normally produced by ANP-activated GC-A, prevents myocyte Ca2+i increases in response to hypertrophic hormones such as Ang II. However, when cGMP production is impaired or cGMP/PKG I signaling is interrupted, ANP fails to prevent Ca2+i-stimulating effects of Ang II. Even more, binding of ANP to GC-A now directly activates TRPC3/C6 channels within a preformed GC-A–TRPC protein complex. The resulting cation influx activates LTCC currents, ultimately increasing myocyte Ca2+ levels (Fig. 7E). This pathway is important under pathophysiological conditions, such as established pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy, when high endogenous ANP levels desensitize the GC-A receptor and impair its cyclase activity. Our experiments in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes suggest that it can aggravate pathological myocyte growth.

The protein interaction between GC-A and TRPC3/C6 is specific because it was not observed for other members of the TRPC family such as TRPC4 and TRPC5. Our studies with a truncated ANP receptor suggest that this interaction is probably mediated by the KH or the dimerization domain of GC-A. The function of the KH domain is incompletely understood, and kinase activity has not been detected (7). Instead, the KH domain was shown to act as a docking site for association of GC-A with other proteins, such as heat shock protein 90 complexes, an interaction that seems to be important for GC-A stabilization and activity (21). Our studies reveal a protein association that mediates a cGMP-independent signaling pathway of GC-A. ANP binding to GC-A causes a conformational change of the GC-A–TRPC complex (as shown by FRET), which possibly results in allosteric stimulation of channel activity (indicated by our electrophysiological data) when cGMP formation by GC-A is impaired and cGMP/PKG I signaling is interrupted. It was shown in cultured neonatal rat myocytes that cation (Na+, Ca2+) influx through activated TRPC3/C6 channels is associated with a positive change in membrane potential, thereby leading to activation of LTCC (14). Alternatively, our experiments in adult murine myocytes suggest that the small (e.g., ANP provoked) Ca2+ influx through TRPC3/C6 activates calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII) (SI Results; Figs. S3 and S4), which, according to published studies, then may phosphorylate LTCC to facilitate ICa (22). Ultimately, increased ICa triggers the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and is an important determinant of intracellular Ca2+ transients that elicit contraction and growth (23).

In addition, we show that the dual effect of ANP/GC-A on cellular Ca2+i levels also depends on the presence or absence of PKG I. The stimulating effect of ANP was revealed in myocytes with genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of PKG I. Furthermore, FRET and electrophysiology demonstrated that ANP modulates the conformation of the TRPC3/GC-A complex and stimulates channel activity in transfected HEK293 cells, which lack endogenous PKG I (16). Importantly, coexpression of PKG I in HEK293 cells had no effect on the ANP-induced conformational change (indicating that this phenomenon is cGMP/PKG I independent) but prevented subsequent stimulation of channel activity by ANP, possibly through PKG I-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of the TRPC3/C6 channel (4–6, 24). It is likely that different native cell types have different endogenous expression levels of PKG I and thereby respond differently to activation of GC-A (25). For example, the NP/GC-A system inhibits proliferation of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells but stimulates proliferation of endothelia as well as growth and Ca2+i-dependent insulin secretion of pancreatic β-cells (1). Our finding that ANP/GC-A exerts different effects on TRPC channel activity and intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, depending on the cGMP responses and the presence or absence of PKG I, provides insights that could potentially explain these seemingly different cellular responses. Hence, our discovery of cGMP-independent signaling of GC-A opens the way for further studies on the role of this receptor in various (patho)physiological processes.

Materials and Methods

Detailed materials and methods are described in SI Materials and Methods, including genetic mouse models, transverse aortic constriction surgery, Northern and Western blotting, determination of plasma ANP levels, chronic ANP administration, determination of intracellular cGMP levels in myocytes and HEK293 cells, measurements of LTCC currents and Ca2+i transients in adult murine ventricular myocytes, electrophysiological recordings in transfected HEK293 cells, plasmids, immunoprecipitation of GC-A and TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, or TRPC6 from HEK293 cells and cardiomyocytes, FRET measurements, guanylyl cyclase assay with membranes from HEK293 cells, and studies of cell growth in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Karina Zimmermann for neonatal rat cardiomyocyte isolation and Prof. Veit Flockerzi (Experimentelle und Klinische Pharmakologie und Toxikologie, Universität des Saarlandes, Homburg, Germany) for the plasmids for expression of TRPC3/C4/C5/C6 channels in HEK293 cells and for specific antibodies for detection of TRPC4 and TRPC5. This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 487 and 688) and Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung-Würzburg (to M. Kuhn). M. Kruse was partly supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS08174.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103300108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kuhn M. Structure, regulation, and function of mammalian membrane guanylyl cyclase receptors, with a focus on guanylyl cyclase-A. Circ Res. 2003;93:700–709. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000094745.28948.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtwick R, et al. Pressure-independent cardiac hypertrophy in mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted inactivation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor guanylyl cyclase-A. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1399–1407. doi: 10.1172/JCI17061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klaiber M, et al. Novel insights into the mechanisms mediating the local antihypertrophic effects of cardiac atrial natriuretic peptide: Role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase and RGS2. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinoshita H, et al. Inhibition of TRPC6 channel activity contributes to the antihypertrophic effects of natriuretic peptides-guanylyl cyclase-A signaling in the heart. Circ Res. 2010;106:1849–1860. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koitabashi N, et al. Cyclic GMP/PKG-dependent inhibition of TRPC6 channel activity and expression negatively regulates cardiomyocyte NFAT activation novel mechanism of cardiac stress modulation by PDE5 inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishida M, et al. Phosphorylation of TRPC6 channels at Thr69 is required for anti-hypertrophic effects of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13244–13253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter LR. Domain analysis of human transmembrane guanylyl cyclase receptors: Implications for regulation. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1205–1220. doi: 10.2741/1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogawa H, Qiu Y, Ogata CM, Misono KS. Crystal structure of hormone-bound atrial natriuretic peptide receptor extracellular domain: Rotation mechanism for transmembrane signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28625–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313222200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKie PM, et al. The prognostic value of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide for death and cardiovascular events in healthy normal and stage A/B heart failure subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2140–2147. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryan PM, Potter LR. The atrial natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR-A/GC-A) is dephosphorylated by distinct microcystin-sensitive and magnesium-dependent protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16041–16047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schröter J, et al. Homologous desensitization of guanylyl cyclase A, the receptor for atrial natriuretic peptide, is associated with a complex phosphorylation pattern. FEBS J. 2010;277:2440–2453. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan D, Bryan PM, Antos LK, Potthast RJ, Potter LR. Down-regulation does not mediate natriuretic peptide-dependent desensitization of natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR)-A or NPR-B: Guanylyl cyclase-linked natriuretic peptide receptors do not internalize. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(1):174–183. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber S, et al. Rescue of cGMP kinase I knockout mice by smooth muscle specific expression of either isozyme. Circ Res. 2007;101:1096–1103. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onohara N, et al. TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 2006;25:5305–5316. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He LP, Hewavitharana T, Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Gill DL. A functional link between store-operated and TRPC channels revealed by the 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazole derivative, BTP2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10997–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiedler B, et al. cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I inhibits TAB1-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase apoptosis signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32831–32840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zitt C, et al. Expression of TRPC3 in Chinese hamster ovary cells results in calcium-activated cation currents not related to store depletion. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1333–1341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson DK, Garbers DL. Dominant negative mutations of the guanylyl cyclase-A receptor. Extracellular domain deletion and catalytic domain point mutations. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:425–430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eder P, Molkentin JD. TRPC channels as effectors of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2011;108:265–272. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poteser M, et al. TRPC3 and TRPC4 associate to form a redox-sensitive cation channel. Evidence for expression of native TRPC3-TRPC4 heteromeric channels in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13588–13595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar R, Grammatikakis N, Chinkers M. Regulation of the atrial natriuretic peptide receptor by heat shock protein 90 complexes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11371–11375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaich A, et al. Facilitation of murine cardiac L-type Ca(v)1.2 channel is modulated by calmodulin kinase II-dependent phosphorylation of S1512 and S1570. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10285–10289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914287107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwan HY, Huang Y, Yao X. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential isoform 3 (TRPC3) channel by protein kinase G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2625–2630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304471101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin G, et al. Effect of cell passage and density on protein kinase G expression and activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92(1):104–112. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.