Abstract

The phytohormone auxin plays critical roles in the regulation of plant growth and development. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) has been recognized as the major auxin for more than 70 y. Although several pathways have been proposed, how auxin is synthesized in plants is still unclear. Previous genetic and enzymatic studies demonstrated that both TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS (TAA) and YUCCA (YUC) flavin monooxygenase-like proteins are required for biosynthesis of IAA during plant development, but these enzymes were placed in two independent pathways. In this article, we demonstrate that the TAA family produces indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPA) and the YUC family functions in the conversion of IPA to IAA in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) by a quantification method of IPA using liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem MS. We further show that YUC protein expressed in Escherichia coli directly converts IPA to IAA. Indole-3-acetaldehyde is probably not a precursor of IAA in the IPA pathway. Our results indicate that YUC proteins catalyze a rate-limiting step of the IPA pathway, which is the main IAA biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis.

Keywords: plant hormone, metabolism

Auxin plays fundamental roles in plant growth and development. Auxin regulates cell division, cell expansion, cell differentiation, lateral root formation, flowering, and tropic responses (1). After the discovery of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in the 1930s, auxin has been virtually synonymous with IAA for more than 70 y. Recent studies demonstrated that IAA directly interacts with the F-box protein TIR1, and promotes the degradation of the Aux/IAA transcriptional repressors to activate diverse auxin responsive genes (2–4). Despite the importance of IAA in plants, IAA biosynthesis is not fully understood, most likely because of the existence of multiple pathways and functional redundancy of enzymes within the pathway (5, 6).

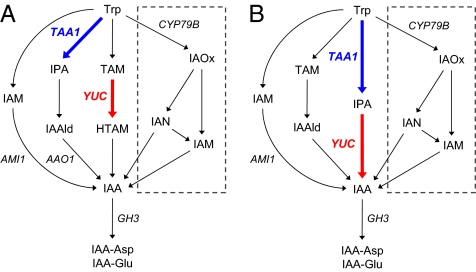

Genetic and biochemical studies indicated that tryptophan (Trp) is the main precursor for IAA in plants (5, 6). Alternatively, the Trp-independent pathway has been proposed for IAA biosynthesis, but a genetic basis for this pathway has not been defined (6–8). There are four proposed pathways for biosynthesis of IAA from Trp in plants: (i) the YUCCA (YUC) pathway, (ii) the indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPA) pathway, (iii) the indole-3-acetamide (IAM) pathway, and (iv) the indole-3-acetaldoxime (IAOx) pathway (previously called the CYP79B pathway), as shown in Fig. 1A (6, 9). Recent studies indicated that the IAOx pathway operates in relatively few plant species that have CYP79B family members to convert Trp to IAOx (9–13). IAOx was identified in Arabidopsis, but not from CYP79B-deficient mutants and several noncrucifer plants (9, 14, 15). The IAM pathway has been suggested to exist widely in plants, but it remains unclear exactly how IAM is produced (16). The conversion of IAM to IAA by Arabidopsis AMIDASE 1 (AMI1) has been demonstrated (17). The physiological significance of the IAM pathway in plants is under investigation.

Fig. 1.

Proposed IAA biosynthesis pathway in plants. (A) Previously proposed IAA biosynthesis pathway. (B) The IAA biosynthesis pathway proposed in the present study. The bold arrows indicate proposed functions of TAA1 and YUC, respectively. The IAOx pathway is illustrated in a dotted square. IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu are IAA metabolites investigated in this study.

The YUC pathway has been proposed as a common IAA biosynthetic pathway that produces auxin essential for embryogenesis, flower development, seedling growth, and vascular patterning (18–21). YUC genes have been identified ubiquitously in various plant species (22). In maize, a monocot-specific YUC-like protein SPARSE INFLORESCENCE 1 (SPI1) plays critical roles in vegetative and reproductive development (22). YUC family encode flavin monooxygenase-like proteins that catalyze a rate-limiting step in IAA biosynthesis (23). Arabidopsis yuc1D mutants, in which YUC1 is expressed under the control of cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, show slightly increased IAA levels along with high-auxin phenotypes such as elongated hypocotyls, epinastic leaves, and enhanced apical dominance (23). Arabidopsis has 11 YUC genes, and yuc multiple KO mutants show severe auxin-deficient phenotypes (19, 20). YUC catalyzes the conversion of tryptamine (TAM) to N-hydroxy-TAM (HTAM) in vitro (23, 24). IAOx and indole-3-acetonitrile (IAN) were previously proposed as possible intermediates in the conversion of HTAM to IAA (23). However, our previous study indicated that IAOx and IAN are not common intermediates of IAA biosynthesis in plants (9). The underlying pathway from HTAM to IAA is still unknown.

More recent studies have isolated three Arabidopsis mutants—shade avoidance 3, weak ethylene insensitive 8 (wei8), and transport inhibitor response 2—in which the TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS 1 (TAA1) gene is disrupted (25–27). TAA1 mediates the conversion of Trp to IPA in the first step of the IPA pathway (Fig. 1A). TAA1 plays critical roles in embryogenesis, flower development, seedling growth, vascular patterning, lateral root formation, tropism, shade avoidance, and temperature-dependent hypocotyl elongation (25–27). There are two TAA1-related proteins—TAR1 and TAR2—in Arabidopsis. Double-KO mutants of TAA1 and TAR2 genes, wei8 tar2, showed severe growth defects caused by a significant reduction of IAA production in Arabidopsis (26). In maize, VANISHING TASSEL 2 (VT2) gene has been identified to encode a grass-specific TAA1 coorthologue required for vegetative and reproductive development (28). The pathway from IPA to IAA via indole-3-acetaldehyde (IAAld) by IPA DECARBOXYLASE (IPD) and ALDEHYDE OXIDASE (AO) has been proposed (5, 29, 30). However, IPD genes have not yet been identified in plants. There are four AO genes in Arabidopsis. It has been demonstrated that ARABIDOPSIS ALDEHYDE OXIDASE 1 (AAO1) can convert IAAld to IAA (Fig. 1A) (31). AO family requires a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase encoded by ABA DEFICIENT 3 (ABA3) for its enzyme activity (32, 33). However, as aba3-deficient mutants do not show an apparent auxin-deficient phenotype, it is not clear whether the AO family actually participates in IAA biosynthesis in plants.

The IPA and YUC pathways have been proposed to independently produce IAA (Fig. 1A). However, the phenotypic similarities between TAA-deficient and YUC-deficient mutants suggested that TAA and YUC families possibly operate in the same auxin biosynthetic pathway (6, 8). A recent genetic study in maize led to the proposal that VT2 and SPI1, coorthologues of TAA and YUC, may function in the same IAA biosynthetic pathway, as there was no significant change in IAA levels between vt2 spi1 double mutants and vt2 single mutants (28).

Here, we provide genetic, enzymatic, and metabolite-based evidence that TAA and YUC families function in the same auxin biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1B). YUC is implicated in the conversion of IPA to IAA in Arabidopsis. IAAld is probably not a precursor of IAA in the IPA pathway. We conclude that YUC family catalyzes a rate-limiting step of the IPA pathway that produces IAA essential for plant development.

Results

Synergistic Interaction Between TAA and YUC Families in IAA Biosynthesis.

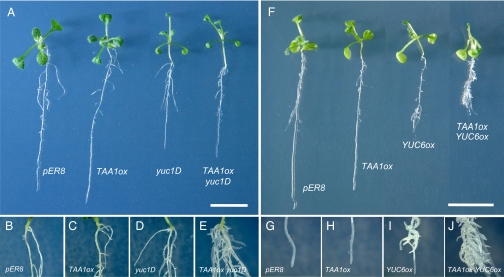

To investigate whether TAA and YUC families act in the same pathway, we generated estradiol (Est)-inducible TAA1 overexpression plants in Arabidopsis WT (TAA1ox) and yuc1D (TAA1ox yuc1D), respectively. We predicted that cooverexpression of TAA1 genes would enhance IAA biosynthesis in yuc1D mutants if TAA1 and YUC1 act in the same pathway. TAA1ox plants did not show apparent phenotypes relative to vector control plants (pER8) on Murashige–Skoog agar media containing Est (Fig. 2 A–C and Fig. S1). This observation strengthens the result of Tao et al. that TAA1 does not mediate a rate-limiting step in IAA biosynthesis (25). We found that the formation of adventitious and lateral roots was significantly enhanced in TAA1ox yuc1D plants relative to that in yuc1D mutants (Fig. 2 A, D, and E and Fig. S1). To determine if overexpression of TAA1 enhances IAA biosynthesis in yuc1D mutants, we analyzed IAA levels in these mutants by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–tandem MS (LC-ESI-MS/MS). We also analyzed the levels of two IAA–amino acid conjugates, IAA-aspartate (IAA-Asp) and IAA-glutamate (IAA-Glu). IAA is metabolized to IAA-Asp, IAA-Glu, and other amino acid conjugates by the GH3 family for homeostatic regulation of auxin in plants (Fig. 1) (34). Hence, the GH3 family may greatly contribute to maintaining the level of IAA if excess amounts of IAA were produced in TAA1ox yuc1D mutants. As shown in Table 1, IAA level increased slightly, but IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu levels did not change, in TAA1ox compared with that in pER8. In yuc1D mutants, IAA levels were not affected, but IAA-Glu levels increased by 6.8 times. We found that both IAA and IAA-Glu levels were 1.5 times and 2.3 times elevated, respectively, in TAA1ox yuc1D relative to that in yuc1D (Table 1). This suggests that GH3 family possibly metabolized excess amounts of IAA in these mutants. A significant increase in total levels of IAA and IAA-Glu in TAA1ox yuc1D relative to yuc1D indicates that TAA1 and YUC1 act synergistically to enhance IAA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypes of TAA1 and YUC overexpression plants in Arabidopsis. (A) Ten-day-old seedlings of pER8, TAA1ox, yuc1D, and TAA1ox yuc1D and (B–E) magnification of stem–root junctions (Est treatment for 5 d). (F) Est-treated 10-d-old seedlings of pER8, TAA1ox, YUC6ox, and TAA1ox YUC6ox and (G–J) magnification of root tip region (Est treatment for 5 d). (Scale bars: 1 cm.)

Table 1.

IAA and IAA amino acid conjugate levels in seedlings of TAA1-, YUC1-, and YUC6-overexpressing plants

| IAA and IAA metabolites (ng/gfw) |

|||

| Plants | IAA | IAA-Asp | IAA-Glu |

| pER8 | 20.6 ± 1.7 | ND | 1.2 ± 0.5 |

| TAA1ox | 29.6 ± 2.1* | ND | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| yuc1D | 25.3 ± 3.4 | ND | 8.1 ± 1.6* |

| TAA1ox yuc1D | 37.2 ± 4.0* | ND | 18.7 ± 5.0*,† |

| YUC6ox | 27.5 ± 2.0* | 61.8 ± 16 | 28.9 ± 4.2* |

| TAA1ox YUC6ox | 50.7 ± 2.0*,† | 5,930 ± 175† | 657 ± 125*,† |

Four-day-old seedlings were transferred to Murashige-Skoog agar media containing Est (10 μM) and grown vertically for 4 d. ND, not detected. Values are mean ± SD, n = 3.

*Significantly different from pER8 plants (P < 0.05, t test).

†Significantly different from either single overexpression line (P < 0.05, t test). In the case of IAA-Asp, significant difference from YUC6ox is shown.

To further demonstrate the tandem action of TAA and YUC families in IAA biosynthesis, we generated Est-inducible YUC6 overexpression plants (YUC6ox) and TAA1 YUC6 cooverexpression plants (TAA1ox YUC6ox) in Arabidopsis (Fig. S1). We predicted that induction of both TAA1 and YUC6 genes would more efficiently enhance IAA biosynthesis relative to induction of TAA1 gene in yuc1D, a weak allele of constitutive YUC1 overexpression mutants. YUC6ox exhibited elongated hypocotyls and petioles, root growth inhibition, and enhanced lateral root and adventitious root formation like yuc1D on Murashige–Skoog agar media containing Est (Fig. 2 F, G, and I and Fig. S1). Similar to that observed in TAA1 yuc1D, adventitious roots and lateral roots were enhanced, but more strongly in TAA1ox YUC6ox cooverexpression plants (Fig. 2 F and H–J and Fig. S1). The level of IAA increased by only 1.8 times, but IAA-Asp and IAA-Glu levels were elevated by 96 and 23 times, respectively, in TAA1ox YUC6ox compared with YUC6ox (Table 1). These results indicate that TAA and YUC families are likely arranged in the same IAA biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis.

TAA Family Mainly Produces IPA from Trp in Arabidopsis.

Enzymatic functions of TAA1 and YUC1/6 have been demonstrated by using their recombinant proteins in vitro (23–26), but their major functions may actually differ in plants. To complement our genetic evidence with a metabolite-based approach, we analyzed possible IAA precursors by using LC-ESI-MS/MS. IPA is an enzymatic reaction product of TAA1 in vitro. IPA is a relatively unstable IAA precursor and nonenzymatically converted to IAA in aqueous solution (35). To avoid the degradation of IPA during the purification, we immediately derivatized IPA with dinitrophenyl hydrazine (DNPH) to a stable hydrazone derivative (DNPH-IPA) in the crude extracts (Fig. S2A). After purification, DNPH-IPA was further derivatized with diazomethane to methyl ester (DM-IPA), and analyzed using LC-ESI-MS/MS in the negative ion mode (Fig. S2 A–J).

By using this IPA analysis method, we tested if IPA is mainly produced from Trp in Arabidopsis. To selectively and efficiently label IAA precursors in the Trp-dependent pathway with stable isotopes, Trp-auxotroph trp1-1 mutants were supplemented with [13C11,15N2]Trp in the liquid media (Fig. S3A) (36). We observed that a parent ion for DM-IPA shows an increase of 12 mass units, indicating a formation of [13C11,15N]IPA in Arabidopsis (Fig. S3B). From the analysis of DM-IPA and [13C11,15N]DM-IPA, 95% of total IPA was efficiently labeled in this condition, in which 91% of total IAA was labeled (Fig. S3 C and D). This result indicated that IPA is mainly produced from Trp in Arabidopsis.

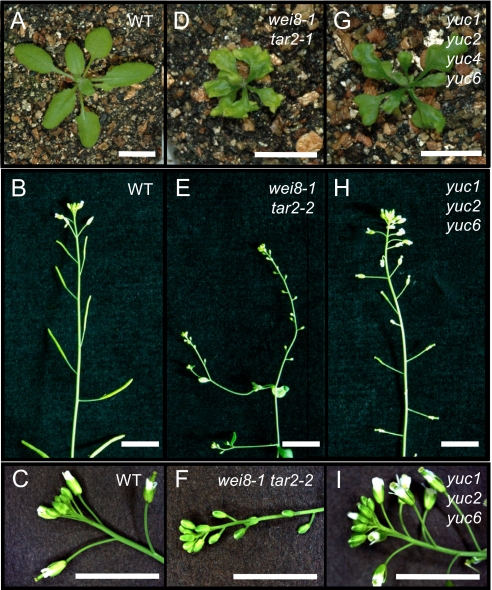

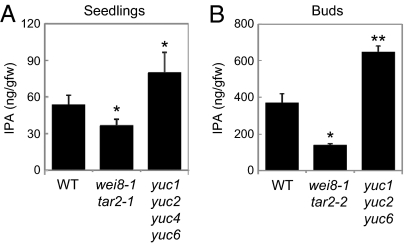

By using a synthetic [13C11,15N]IPA as an internal standard, we quantified IPA levels in Arabidopsis. The level of IPA in 3-wk-old WT seedlings was 53.8 ± 7.5 ng/gfw (Figs. 3A and 4A). IPA levels may vary depending on tissue type, growth stage, and environmental conditions (37). A recent study indicated that upper inflorescences produce relatively higher levels of IAA compared with other vegetative tissues in Arabidopsis (24). We found that the level of IPA increased by 6.9 times in the buds relative to that in WT seedlings (Figs. 3 A–C and 4 A and B). The endogenous level of IAA increased 5.1 times in the buds (53.6 ± 16 ng/gfw; n = 3) relative to that in WT seedlings (10.6 ± 1.6 ng/gfw; n = 3). We note that IPA levels may also vary depending on plant species, as the moss Physcomitrella patens gametophytes accumulate 25.0 ± 2.1 ng/gfw (n = 4) and maize leaves involve 39.4 ± 7.2 ng/gfw (n = 5) of endogenous IPA, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of TAA-deficient and YUC-deficient mutants. (A) Three-week-old WT seedlings. (B) Upper region and (C) inflorescence of 7-wk-old WT plants. (D) Three-week-old seedlings of wei8-1 tar2-1 mutants. (E) Upper region and (F) inflorescence of 7-wk-old wei8-1 tar2-2 mutants. (G) Three-week-old seedlings of yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 mutants. (H) Upper region and (I) inflorescence of yuc1 yuc2 yuc6 mutants. (Scale bars: 1 cm.)

Fig. 4.

The level of IPA in WT plants and TAA-deficient and YUC-deficient mutants. (A) Aerial parts of 3-wk-old seedlings grown in soil were used for IPA analysis. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). (B) The buds of 7-wk-old plants before flowering were used for IPA analysis. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Differences between WT and mutants are statistically significant at P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, t test).

To investigate whether TAA1 produces IPA in vivo, we analyzed IPA levels in 3-wk-old seedlings of TAA-deficient wei8-1 tar2-1 double mutants (Fig. 3D). The level of IPA was reduced by 32% in wei8-1 tar2-1 compared with that in WT seedlings (Fig. 4A). We also analyzed IPA levels in the buds of wei8-1 tar2-2 double mutants, a weaker TAA-deficient mutant that is able to make flowers (Fig. 3 E and F). The level of IPA was reduced by 62% in the buds of the double mutants compared with WT plants (Fig. 4B). Moreover, we analyzed the level of IPA in TAA1ox (Fig. 2A). IPA levels were increased 2.9 times in TAA1ox relative to that in pER8 seedlings (Table 2). These results provide in vivo evidence that TAA family plays a major role in the production of IPA in Arabidopsis.

Table 2.

IAA and IAA precursor and IAA metabolite levels in TAA1- and YUC6-overexpressing plants

| IAA, IAA precursors, and IAA metabolites (ng/gfw) |

|||||

| Plants | IPA | IAAld | IAA | IAA-Asp | IAA-Glu |

| pER8 | 56.0 ± 8.0 | 11.3 ± 2.2 | 16.1 ± 1.0 | ND | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| TAA1ox | 165 ± 12* | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 19.5 ± 1.4 | ND | 0.5 ± 0.1* |

| YUC6ox | 37.5 ± 4.0* | 9.9 ± 1.9 | 23.7 ± 5.1 | 28.0 ± 5.8 | 10.7 ± 2.5* |

Eleven-day-old seedlings were transferred to Murashige-Skoog agar media containing Est (10 μM) and grown vertically for 3 d. ND, not detected. Values are mean ± SD, n = 3 except for IPA (n = 4).

*Significantly different from pER8 plants (P < 0.05, t test).

YUC Catalyzes Conversion of IPA to IAA.

A previous study showed that YUC1 converts TAM to HTAM in vitro (23). To investigate whether TAM metabolism is affected in YUC-deficient mutants, we analyzed TAM levels in yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 quadruple mutants by using 15N2-TAM as an internal standard (Fig. 3G). However, no significant accumulation of TAM was observed in 3-wk-old seedlings of yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 (209 ± 4 pg/gfw; n = 3) relative to that in WT seedlings (209 ± 15 pg/gfw; n = 3). This result suggests that YUC may not catalyze conversion of TAM to HTAM in vivo (38).

To examine whether YUC family acts in the conversion of IPA to IAA in the IPA pathway, we analyzed IPA levels in the seedlings of yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 quadruple mutants (Fig. 3G). We found that the level of IPA increased 1.5 times in yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 relative to that in WT seedlings (Fig. 4A). We further analyzed IPA levels in the buds of yuc1 yuc2 yuc6 triple mutants, weaker alleles that form flowers (Fig. 3 H and I). Similarly, the level of IPA was increased significantly (1.8 times) in the buds of yuc1 yuc2 yuc6 compared with that in the buds of WT (Fig. 4B). In contrast, IPA levels were 33% reduced in YUC6ox plants relative to that in pER8 plants (Table 2). These results demonstrate that YUC family is most likely implicated in the conversion of IPA to IAA in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1B).

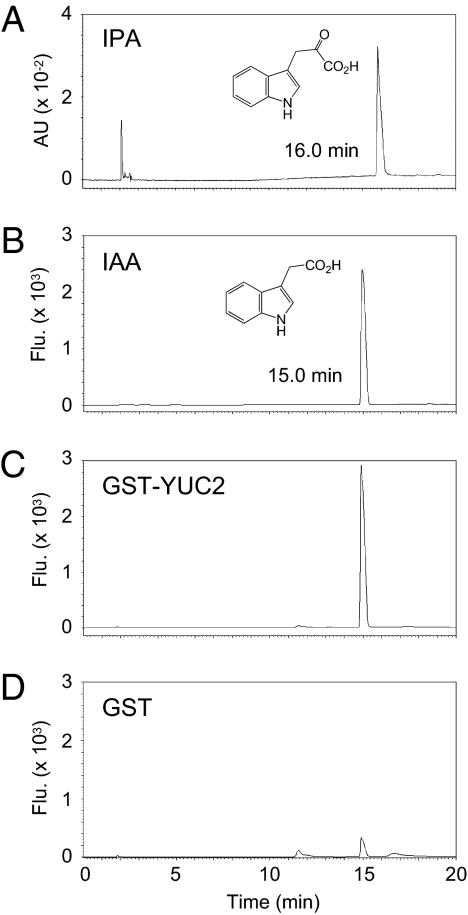

To provide direct evidence that YUC catalyzes the conversion of IPA to IAA, we performed an enzyme assay by using GST-fused YUC2 (GST-YUC2) heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli. Purified GST-YUC2 actively converted IPA to IAA in an NADPH-dependent manner (Fig. 5 A–C and Fig. S4A). Only small amounts of IAA were produced nonenzymatically from IPA in a control reaction containing GST (Fig. 5D). The production of IAA was confirmed by LC-ESI-MS/MS (Fig. S4B). No conversion of IPA to IAAld by GST-YUC2 was observed. TAM was not a substrate of GST-YUC2 in our assay condition (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 5.

Conversion of IPA to IAA by YUC2. (A) The HPLC profile for authentic IPA with UV detection (328 nm). (B) The HPLC profile for authentic IAA, (C) GST-YUC2 reaction mixture, and (D) GST reaction mixture with fluorescence detection (280 nm excitation and 355 nm emission).

IAAld Is Probably Not Involved in IPA Pathway.

Direct conversion of IPA to IAA by YUC2 protein indicates that IAAld is probably not involved in the IPA pathway. To complement our in vitro evidence, we investigated the biosynthesis pathway for IAAld in Arabidopsis. IAAld was previously identified in Arabidopsis using GC-MS (39), yet a reliable and definitive IAAld analysis method has not been established. We converted IAAld to its stable hydrazone derivative (DNPH-IAAld) in the crude extracts (Fig. S5A), and analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS in the negative ion mode (Fig. S5 B–I).

We tested whether IAAld is mainly produced from Trp in Arabidopsis by feeding a [13C11,15N2]Trp to trp1-1 (Fig. S6A). We detected a parent ion for DNPH-IAAld with increase of 11 mass units, suggesting a formation of [13C10,15N]IAAld in Arabidopsis (Fig. S6B). Analysis of 13C and 15N-incorporation rate indicates that 99% of total IAAld was labeled under this condition, in which 91% of total IAA was labeled (Fig. S6C). This result indicated that IAAld is mainly produced from Trp in Arabidopsis.

By using a synthetic [13C10,15N]IAAld as an internal standard, the level of IAAld was quantified as 15.1 ± 5.3 ng/gfw (n = 3) in 2-wk-old WT seedlings of Arabidopsis. Although the IPA levels were increased drastically in TAA1ox plants, IAAld levels did not show a significant change relative to that in pER8 (Table 2). We further observed that IAAld levels were not reduced, but rather increased, in the buds of wei8-1 tar2-2 mutants (33.9 ± 3.9 ng/gfw; n = 2) compared with WT (23.8 ± 1.7 ng/gfw; n = 2), in which IPA levels were reduced (Fig. 4B). Moreover, IAAld levels were not affected in YUC6ox, in which IAA–amino acid conjugate levels were significantly increased (Table 2). These observations indicate that IAAld is most likely not implicated in the IPA pathway, but in another Trp-dependent pathway.

We examined whether the AO family is involved in IAA biosynthesis by analyzing IAAld levels in aba3 mutants, in which all AO members are inactivated. IAAld levels would be increased if the AO family were implicated in the oxidation of IAAld in plants. However, no increase of IAAld levels was observed in aba3 mutants (15.0 ± 2.5 ng/gfw; n = 3) compared with that in WT plants (15.1 ± 5.3 ng/gfw; n = 3), in which IAA and IAA-Glu levels were also not significantly changed (Fig. S7). This result indicates that the AO gene family probably does not play a role in IAA biosynthesis.

Discussion

We provide multiple lines of evidence that the TAA family produces IPA and the YUC family catalyzes the conversion of IPA to IAA in Arabidopsis. TAA and/or YUC families play critical roles in embryogenesis, flower development, seedling growth, vascular patterning, lateral root formation, tropism, shade avoidance, and temperature-dependent hypocotyl elongation (19, 20, 25–27). Thus, we conclude that the IPA pathway is the major IAA biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. The YUC family mediates a rate-limiting step in the IPA pathway. TAA1 and YUC can act synergistically to enhance IAA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Table 1). The expression patterns of TAA and YUC families are spatiotemporally regulated in plant development (19, 20, 25–27). These results indicate that TAA and YUC families may coordinately regulate IAA production. Further analysis of the expression patterns of TAA and YUC families would be a key to understanding the sites and regulation of IPA-dependent IAA biosynthesis in plants.

YUC2 protein catalyzes the direct conversion of IPA to IAA. YUC proteins may function similarly to lactate monooxygenases that convert lactate to acetic acid and CO2 via pyruvate (40). Further kinetic and structural analyses of YUC proteins would clarify the molecular mechanism of IAA formation. IAAld has been proposed as an intermediate of the IPA pathway, but may be in another pathway in Arabidopsis. A recent study suggests that IAAld is an IAA precursor produced from TAM in the pea (Fig. 1B) (14). Quittenden et al. demonstrated that D5-TAM was incorporated to IAAld in pea roots by using GC-MS. TAM and IAAld have been detected in Arabidopsis and pea (9, 14), but genetic evidence has not been provided for the occurrence of the TAM pathway in plants. Trp DECARBOXYLASE (TDC) that catalyzes the conversion of Trp to TAM has been cloned and characterized in some plant species (41, 42). However, TDC genes have not been identified in Arabidopsis. The AO family members have been demonstrated to oxidize IAAld to IAA in vitro, but our results show that AO is probably not involved in IAA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Thus, the TAM pathway may operate in the pea, but it is not clear whether this pathway also exists in other plants.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 was used as the WT control. Transgenic plants used in this study are described in SI Materials and Methods. yuc1 yuc2 yuc6 and yuc1 yuc2 yuc4 yuc6 were generated from yuc1/− yuc2/+ yuc4/+ yuc6/− plants, wei8-1 tar2-1 from wei8-1/− tar2-1/+, and wei8-1 tar2-2 from wei8-1/− tar2-2/+ (19, 26). The trp1-1 and aba3-1 mutants were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). After imbibitions at 4 °C for 2 d, surface-sterilized seeds were germinated on Murashige–Skoog agar media (pH 5.7) supplemented with thiamin hydrochloride (3 μg/mL), nicotinic acid (5 μg/mL), pyridoxine hydrochloride (0.5 μg/mL), myoinositol (100 μg/mL), 1% (wt/vol) sucrose, and 0.8% agar. Plants were grown at 21 °C under continuous white light (30–50 μmol⋅m−2⋅s−1). When grown on soil, 2-wk-old seedlings were transferred to soil and cultivated in a temperature-controlled chamber.

Chemical Synthesis, LC-ESI-MS/MS, Labeling Experiments, and Enzyme Assay.

[13C11,15N]IPA, [13C10,15N]IAAld, [13C4,15N]IAA-Asp, and [13C5,15N]IAA-Glu were synthesized as described in SI Materials and Methods. LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of IAA and IAA precursors, in vivo labeling experiments, and YUC enzyme assay were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods and Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Belay T. Ayele for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Tomohisa Kuzuyama, Mr. Taro Ozaki, and Dr. Eiji Okamura for helpful comments on YUC enzyme assay. We thank Prof. Nam-Hai Chua for providing the pMDC7 vector, the RIKEN BioResource Center for providing the TAA1 cDNA clone, and ABRC for providing seeds of trp1-1 and aba3-1 and a cDNA clone of YUC6. We are grateful to Ms. Aya Ide for assistance in preparing plant materials and genotyping of yuc multiple mutants. This work was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grants 22780108 (to K.M.), 22570058 (to T.S.), 19678001 (to K.S.), and 19780090 (to H. Kasahara); JSPS Grant L-11556 (to Y.Z.); National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM68631 (to Y.Z.); Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan Special Coordination Funds for the Promoting of Science and Technology (T.S.); a matching fund subsidy for private universities (K.H.); and Strategic Programs for Research and Development (President's Discretionary Fund) of RIKEN (H. Kasahara).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. E.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1108434108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Davies PJ. The Plant Hormone: Their Nature, Occurrence, and Functions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dharmasiri N, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005;435:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature03543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kepinski S, Leyser O. The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005;435:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nature03542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan X, et al. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2007;446:640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature05731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodward AW, Bartel B. Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot (Lond) 2005;95:707–735. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen JD, Slovin JP, Hendrickson AM. Two genetically discrete pathways convert tryptophan to auxin: More redundancy in auxin biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:197–199. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strader LC, Bartel B. A new path to auxin. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:337–339. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0608-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugawara S, et al. Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5430–5435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811226106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bak S, Nielsen HL, Halkier BA. The presence of CYP79 homologues in glucosinolate-producing plants shows evolutionary conservation of the enzymes in the conversion of amino acid to aldoxime in the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides and glucosinolates. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:725–734. doi: 10.1023/a:1006064202774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hull AK, Vij R, Celenza JL. Arabidopsis cytochrome P450s that catalyze the first step of tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikkelsen MD, Hansen CH, Wittstock U, Halkier BA. Cytochrome P450 CYP79B2 from Arabidopsis catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetaldoxime, a precursor of indole glucosinolates and indole-3-acetic acid. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33712–33717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, et al. Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3100–3112. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quittenden LJ, et al. Auxin biosynthesis in pea: Characterization of the tryptamine pathway. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1130–1138. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.141507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nonhebel H, et al. Redirection of tryptophan metabolism in tobacco by ectopic expression of an Arabidopsis indolic glucosinolate biosynthetic gene. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann T, Hoffmann M, Hentrich M, Pollmann S. Indole-3-acetamide-dependent auxin biosynthesis: A widely distributed way of indole-3-acetic acid production? Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollmann S, Neu D, Weiler EW. Molecular cloning and characterization of an amidase from Arabidopsis thaliana capable of converting indole-3-acetamide into the plant growth hormone, indole-3-acetic acid. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:293–300. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobeña-Santamaria R, et al. FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev. 2002;16:753–763. doi: 10.1101/gad.219502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2430–2439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto Y, Kamiya N, Morinaka Y, Matsuoka M, Sazuka T. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1362–1371. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallavotti A, et al. sparse inflorescence1 encodes a monocot-specific YUCCA-like gene required for vegetative and reproductive development in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15196–15201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805596105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, et al. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science. 2001;291:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JI, et al. yucca6, a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis, affects auxin accumulation and auxin-related phenotypes. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:722–735. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao Y, et al. Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell. 2008;133:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stepanova AN, et al. TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell. 2008;133:177–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada M, Greenham K, Prigge MJ, Jensen PJ, Estelle M. The TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE2 gene is required for auxin synthesis and diverse aspects of plant development. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:168–179. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips KA, et al. vanishing tassel2 encodes a grass-specific tryptophan aminotransferase required for vegetative and reproductive development in maize. Plant Cell. 2011;23:550–566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koga J, Adachi T, Hidaka H. Purification and characterization of indolepyruvate decarboxylase. A novel enzyme for indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis in Enterobacter cloacae. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15823–15828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sekimoto H, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of aldehyde oxidases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:433–442. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seo M, et al. Higher activity of an aldehyde oxidase in the auxin-overproducing superroot1 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:687–693. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong L, Ishitani M, Lee H, Zhu JK. The Arabidopsis LOS5/ABA3 locus encodes a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase and modulates cold stress- and osmotic stress-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2063–2083. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bittner F, Oreb M, Mendel RR. ABA3 is a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase required for activation of aldehyde oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40381–40384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staswick PE, et al. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell. 2005;17:616–627. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.026690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bentley JA, Farrar KR, Housley S, Smith GF, Taylor WC. Some chemical and physiological properties of 3-indolylpyruvic acid. Biochem J. 1956;64:44–49. doi: 10.1042/bj0640044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Last RL, Fink GR. Tryptophan-requiring mutants of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 1988;240:305–310. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4850.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tam YY, Normanly J. Determination of indole-3-pyruvic acid levels in Arabidopsis thaliana by gas chromatography-selected ion monitoring-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 1998;800:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)01051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tivendale ND, et al. Reassessing the role of N-hydroxytryptamine in auxin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:1957–1965. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.165803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barlier I, et al. The SUR2 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes the cytochrome P450 CYP83B1, a modulator of auxin homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14819–14824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260502697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Müh U, Massey V, Williams CH., Jr Lactate monooxygenase. I. Expression of the mycobacterial gene in Escherichia coli and site-directed mutagenesis of lysine 266. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7982–7988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Luca V, Marineau C, Brisson N. Molecular cloning and analysis of cDNA encoding a plant tryptophan decarboxylase: comparison with animal dopa decarboxylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2582–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamazaki Y, Sudo H, Yamazaki M, Aimi N, Saito K. Camptothecin biosynthetic genes in hairy roots of Ophiorrhiza pumila: Cloning, characterization and differential expression in tissues and by stress compounds. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:395–403. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.