Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of phosphated titanium and EMD on osteoblast function.

Materials and Methods

Primary rat osteoblasts were cultured on discs of either phosphated or non-phosphated titanium and in half of the samples 180μg of EMD was immediately added. Media was changed every 2 days for 28 days, and then analyzed by TGF-β1 and IL-1β ELISAs. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and light microscopy (LM) was used to evaluate nodule formation and mineralization.

Results

Microscopic evaluation revealed no differences in osteoblast attachment on all discs, regardless of treatment. Osteoblast nodule formation was observed in all groups. In the absence of mineralizing media, nodules on the non-phosphated titanium samples showed no evidence of mineralization. All nodules on the phosphated titanium had evidence of mineralization. ELISA analysis revealed no significant differences in IL-1β production between any of the groups. The EMD treated osteoblasts produced significantly more TGF-β1 than non-EMD treated cells for up to 8 days, and osteoblasts on phosphated titanium produced significantly more Tgf-ß1 at 8 days.

Discussion and Conclusion

Osteoblast attachment appeared unaffected by surface treatment. EMD initiated early TGF-β1 production, but production decreased to control levels within 10 days. Phosphated titanium increased Tgf-ß1 production at 8 days, and induced nodule mineralization even in the absence of mineralizing medium.

Keywords: phosphate, titanium, osteoblasts, enamel matrix derivatives, TGF-β1, IL-1β

INTRODUCTION

Dental implants have become a widely accepted means of routine tooth replacement. A recent study by Karoussis and associates (1) showed that over a ten year period, implants had a success rate of 96.5% in patients who had no history of chronic periodontitis and 90.5% in those who had. Implant success rates have proven to be consistently high for non-risk patients, but it is the patients at high risk for implant failure that warrant research for improved implant surfaces to increase success rates. Some examples of high risk patients are smokers, poorly controlled diabetics, osteoporotic women and patients with a history of aggressive periodontal disease. Implant failure rates in smokers have been shown to be twice as high as non-smokers (2,3) and human studies have shown greater long-term implant failure rates in diabetic patients compared to patients without diabetes (4,5).

Many different surface coatings of titanium implant substrates have been tested to improve osseointegration. Any surface that increases successful implant retention in high risk patients would be beneficial. Some of the surfaces studied include smooth, plasma sprayed, and sand-blasted, acid-etched (SBAE) (6). These surface treatments were found to influence the growth and metabolic activity of cultured osteoblasts, with SBAE surfaces yielding the most favorable results (6).

Recently, a new titanium surface resulting from electronically coating titanium with phosphate was developed and studied in orthopedic implants (Minevski, personal communication). When titanium is treated by anodic oxidation in phosphoric acid, the phosphate concentration of the surface is increased and the titanium becomes more corrosion resistant and the surface hardness improves, facilitating biocompatibility (7). In a canine study evaluating electrolytic phosphated titanium implants placed in the humerus, the treated titanium had significantly enhanced implant contact with bone and decreased the fibrous tissue interface when compared to the non-treated group at one month (7). It is known that for bone formation to occur phosphate and calcium are required (8), so by treating the titanium with phosphate, osseointegration of titanium with bone may be accelerated.

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) has received attention because of its role as a pro-inflammatory cytokine. IL-1β induces bone resorption, an activity reversed by the action of TGF-ß1 (9). IL-1β is the major inflammatory cytokine occurring in gingiva associated with periodontitis (10) and levels of IL-1β have been shown to be higher in periodontitis sites compared to healthy sites (11,12). Increased levels of IL-1β have also been shown around implants with peri-implantitis (13–15).

TGF-β1 production by osteoblasts is useful in evaluating the early stages of osteoblast response to exposure to new surfaces (e.g., dental implants). TGF-β1 is abundant in bone matrix (16,17) and has been shown to affect bone metabolism through modulation of both osteoclastic and osteoblastic cell differentiation and activity (17–21). It has been suggested that TGF-β1 may play a role in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of periodontal disease (22). Grafting materials influence the expression of TGF-β1; Trasatti and associates (23) found that Pepgen P-15 (bovine bone with synthetic P15 protein) caused as increased expression of TGF-β1. Moreover, osteoblasts produce TGF-β, which is embedded in the bone matrix and is activated by bone resorbing osteoclasts (24). Since IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine whose activity is suppressed by TGF-β1 (9, 25), the evaluation of these two cytokines together would yield helpful insights as to the biological response of osteoblasts exposed to a new titanium surface.

More recently porcine-derived enamel matrix derivatives (EMD; e.g., Emdogain® (Straumann/Biora, Malmo, Sweden)), have gained attention due to their ability to induce periodontal regeneration (26). Hammarström and associates (26) used preparations of EMD in a monkey model and at 8 weeks found that EMD proteins significantly regenerated buccal defects, including reappearance of acellular cementum with inserting collagen fibers (Sharpey’s fibers) and the formation of new alveolar bone. Other studies have also demonstrated the periodontal regenerative effects of EMD in human models (27,28). EMD has recently been shown to increase FGF-2 expression when added to human osteoblasts (29). The full effects of EMD on the expression of other growth factors are still not known.

Shimizu-Ishiura and associates (30) evaluated the use of EMD on trabecular bone induction after pure titanium implantation in the rat femur. They noted 30 days post implantation that the EMD sites had significantly greater trabecular bone formation than sites which did not receive EMD. Casati and associates (31) evaluated guided bone regeneration (GBR) around implants and found that EMD plus GBR around titanium implants was superior to GBR alone. Franke Stenport and associates (32) evaluated EMD placed in implant osteotomies at the time of implantation. However, they found no significant differences between implants, with and without EMD. Since conflicting results were noted, it was felt that further research is necessary to further evaluate the influence of EMD on osteoblast behavior in contact with titanium.

An in vitro osteoblast culture model was used to evaluate the effects of phosphated versus non-phosphated titanium on osteoblast function and to evaluate the added effect of EMD. These in vitro studies were designed to critically assess osteoblast responses to the surface phosphate, since phosphate is required for successful matrix mineralization by osteoblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture & Preparation

All procedures were approved by the Baylor College of Dentistry (BCD) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Primary rat osteoblasts were harvested from fetal day 20 rat calvaria as previously described by Williams and associates (33). Briefly, 4 pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Industries, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) were housed in the BCD animal care facilities and were sacrificed when the fetuses reached 20 days old. The fetuses were removed onto ice, beheaded, the calvaria removed and the 2 frontal and parietal bones dissected from the surrounding sutures. The bones were cut into small pieces and put into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and stored on ice. The bone pieces were then placed into 2.5 mL digestion solution [(Ca and Mg containing PBS & collagenase (20/mg/mL) (Sigma Chemical Co.)]. After stirring for 20 minutes at 37°C, the supernatant was discarded and considered to be fraction 1. The procedure was repeated and fraction 2 was also discarded, as these two fractions were considered to contain mostly fibroblasts (33). The procedure was repeated another 3 times and fractions 3, 4 & 5 retained and stored on ice. These fractions have been shown to be osteoblast-rich fractions (33). These fractions were combined, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 1.5 minutes, and the pellet was retained while the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was re-suspended with 3 mL of media and divided evenly into three 3 mm x 60 mm dishes. Two mL of culture medium [Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco BRL/Life technologies, Rockville, MD, USA)], 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco BRL/Life technologies), an antibiotic mixture of penicillin (76/ug/mL) and streptomycin (76/ug/mL) (Gibco BRL/Life technologies), 1% ITS (insulin, transferrin and selenium) (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA), and 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco BRL/Life technologies)] were then added to each dish and placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 in air.

The culture media was changed every 2 days. Cells were monitored by light microscope every 24 hours and when confluence was reached they were trypsinized (Ca and Mg free Hank’s plus 0.25 mg/ml trypsin). Subsequently, the cells were divided evenly into 5 new plates. The cells were once again grown to confluence as described above. After the third passage the cells were trypsinized and counted using a hemocytometer.

Culturing Cells on Titanium Discs

Forty eight, 1 cm grade 2 titanium discs (Ti6Al4V), treated by electronic phosphating were supplied by Lynntech, Inc. (College Station, TX, USA). The discs were prepared by the manufacturer by degreasing them in acetone for 10 minutes, and then immersing them in 10% tetrafluoroboric acid for 3 minutes to deoxidize them. The discs were then washed with deionized water for 5–10 seconds and placed in an electrolytic cell. The desired phosphate surface was prepared by the anodic oxidation of titanium samples using 50 volts at room temperature for 30 minutes in 1 M phosphoric acid. These treated discs served as the phosphated titanium group. Forty-eight non-phosphated discs also supplied by the manufacturer served as the non-phosphate control group.

Each disc was placed in one well of a 24-well plate (Costar®, Corning, NY, USA). Discs were divided into 8 groups. Groups 1–4 were phosphate treated, and groups 5–8 were non-phosphate treated. Groups 1 and 5 had 1 disc each, and were control discs receiving no cells, and no EMD. Groups 2 and 6 had 1 disc each, and were control discs with EMD, but no cells. Groups 3 and 7 had 23 discs each, and received 106 cells in 400 μL medium, allowed to settle in an incubator at 5% CO2 in air at 37°C for 1 hour, and then a further 600 μL medium was added. Groups 4 and 8 had 23 discs each, and received 180μg of EMD immediately prior to seeding 106 cells in 400 μL medium, then allowed to settle in an incubator for 1 hour. Thereafter, 600μL of culture media was added to each well and the cells and discs were cultured at 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. Ascorbic acid was added daily to each well at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, and medium was changed at 48-hour intervals.

Preparation of Cells and Discs for Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

On days 6, 10 and 14, five discs from groups 3, 4, 7, and 8 were removed from the media. From day 14 through day 28, one of the remaining discs in each group were cultured with mineralizing medium (1mM β-glycerophosphate and 10−8M dexamethasone in culture medium) to induce nodule mineralization, and a further disc was cultured with regular, non mineralizing medium as a control. After removal from medium, all of the discs were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and dehydrated. After critical point drying, the samples were sputter coated and viewed using SEM (JEOL JSM-6300) (JOEL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA, USA). X-ray energy dispersion analysis (XEDA) was done on the phosphated and non-phosphated surfaces to confirm the presence of mineralized/calcified bone nodules.

Preparation of Cells and Discs for Histological Analysis of Mineralization

The remaining 6 discs in groups 3, 4, 7 and 8 were cultured in regular medium until day 14. At day 14, three discs each from groups 3, 4, 7 and 8 had the culture medium replaced with mineralizing medium. All groups were continued in their respective media until day 28. At day 28 all discs from groups 1–8 were removed from the medium and rinsed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% PFA for 1 hour, then washed with deionized H2O three times. Each disc was then embedded in methylmethacrylate and sections prepared with an Isomet® saw (Buehler®, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) and routine polishing procedures. The discs were stained with Stevenel’s blue and alizarin red, and were evaluated for mineral nodule formation using light microscopy (LM).

Preparation of Supernatants for ELISA Assays

Every 2 days, from day 2 to 14, supernatants were collected from all samples in all groups. The Lowry protein assay (34) was used to assess total protein content in 10μL of supernatant, and bovine serum albumin (1 mg/mL) was used to create the standard curve. Samples were read at 750 nm visible light using Lowry High Sensitivity Software on a Beckman DU-64 Spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). Active TGF-β1 and IL-1β ELISA assays were performed on the supernatants using Quantikine® immunoassay kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions in the 96-well microplates provided. Optical densities were read at 450 nm in a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Spectra MAX, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Methods of Analysis

Surface analysis of cell attachment to each disc was done using a variety of magnifications of SEM and LM. Photographs were taken from pre-designated points on each disc to ensure impartiality of data collection between groups. TGF-β1 and IL-1β levels were expressed as pg of growth factor per μg of total protein. Differences between groups were statistically determined using Student’s t-test and ANOVA. The samples treated with EMD were evaluated in the same manner as all the other groups. The EMD samples were compared to the other sample groups to determine if any differences in the early stages of osteoblast attachment and function occurred.

RESULTS

Cells on SEM and LM

SEM revealed cells attachment to the titanium discs in all groups after six days in culture (Figure 1). Osteoblasts on all surfaces were flattened and spread out, but were not confluent. The groups treated with EMD had a porous and patchy coating present on the surface of the discs with osteoblasts intertwined above and below the EMD. While cellularity appeared to increase in all groups over time, no quantitative assessment was done, and no obvious differences were noted between groups after 28 days in culture (Figure 2).

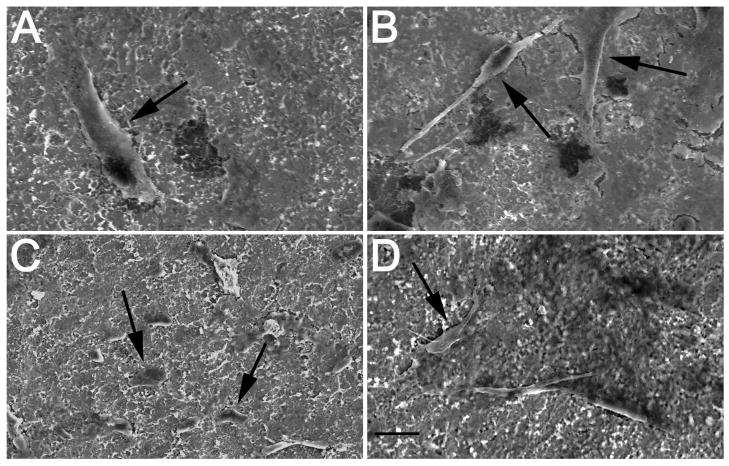

Figure 1.

SEM photos show healthy and flattened osteoblasts (arrows) were present on different titanium surfaces at 6 days (1000x mag.). A. Large osteoblast shown on control surface. B. Multiple osteoblasts intertwined in EMD coating on control plus EMD surface with cytoplasmic processes were easily observed. C. Smaller, but healthy osteoblasts on phosphated titanium surface. D. Osteoblasts on phosphated titanium surface plus EMD. Bar = 10μm

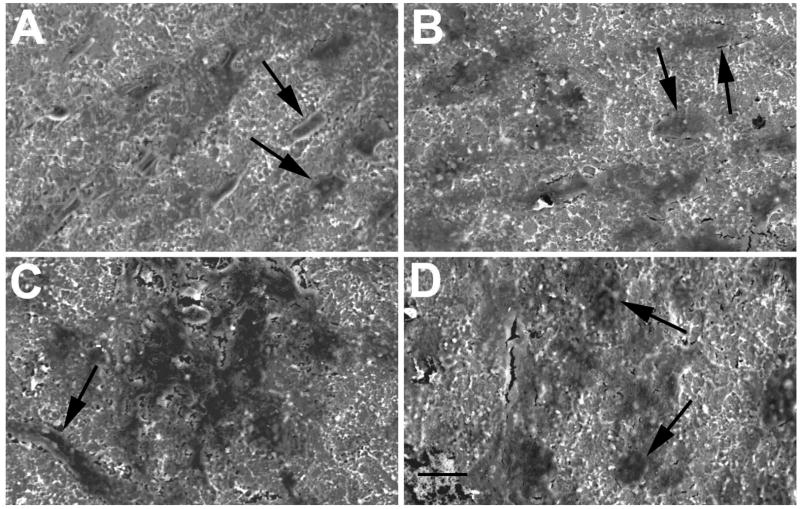

Figure 2.

Day 28 SEM photos of osteoblasts (arrows) on titanium surfaces (1000x mag.). A. Osteoblasts on control surface. B. Osteoblasts on control surface plus EMD. C. Osteoblasts on phosphated titanium surface. D. Osteoblasts on phosphated titanium surface plus EMD. Bar = 10μm

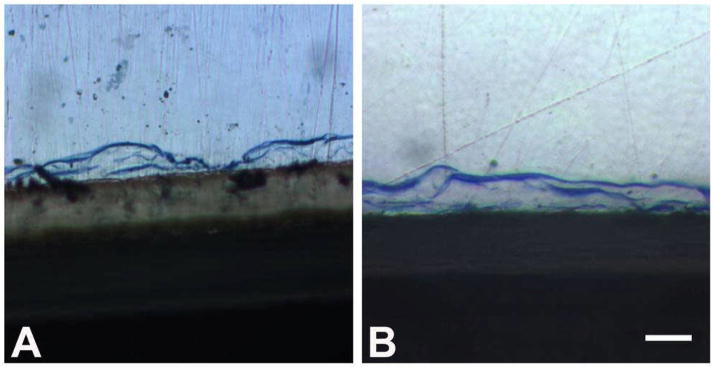

LM confirmed the presence of osteoblasts on all samples in all groups (Figure 3). Blue staining osteoblasts appeared flattened and adhered to the disc surface in all groups, and generally a thickness of 1–2 cell layers was observed. No differences in cellularity or cell morphology were noted between phosphated and non-phosphated groups, and between EMD treated versus non-EMD groups.

Figure 3.

Typical cross section appearance of healthy and flattened blue stained osteoblasts present on titanium surface at 28 days (60x mag.). A. Osteoblasts present on control surface + EMD surface. B. Osteoblasts present on phosphated titanium surface plus EMD. Bar = 50 μm

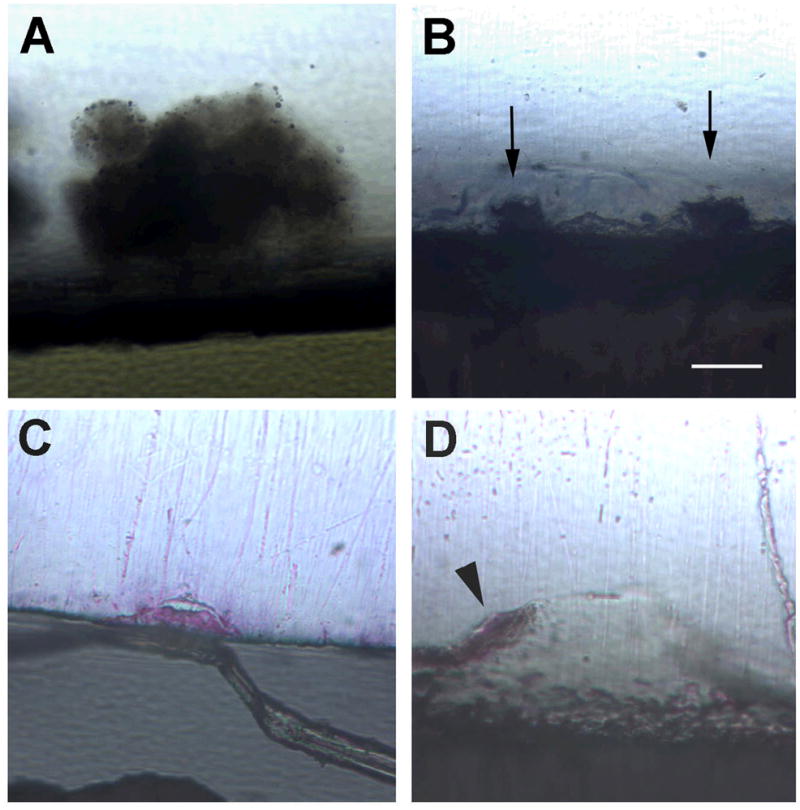

Nodule Formation, Nodule Mineralization, and XEDA Analysis

Nodule formation was observed in all groups, both in the presence and absence of mineralizing medium (Figure 4). Counting of nodules on 2 sections from the two discs from each group prepared for LM showed increased numbers of nodules when EMD was added, but similar numbers of nodules on phosphated versus non-phosphated discs (not shown). Both large and small nodules were noted in all groups. No statistical analysis was done, as numbers of discs and numbers of sections for analysis were too small. All nodules in all groups showed evidence of calcification when mineralizing medium was added (Figure 4). However, in the absence of mineralizing medium, only nodules on the phosphated titanium discs showed evidence of calcification, while the nodules on the non-phosphated titanium discs did not. Calcification was confirmed by alizarin red positive staining on the nodules.

Figure 4.

Cross sections of nodules present on different titanium surfaces, none of which have been treated with mineralizing medium (60x mag.). Mineralization shows red from alizarin red stain. A. Large nodule present on control surface, note mineralization is not seen. B. Two nodules (arrows) present on control surface plus EMD, also with no mineralization seen. C. Nodule present on phosphated titanium surface and mineralization is taking place. D. Large nodule present on phosphated titanium surface plus EMD, with mineralization present over the top of the nodule (arrowhead). Bar = 25 μm

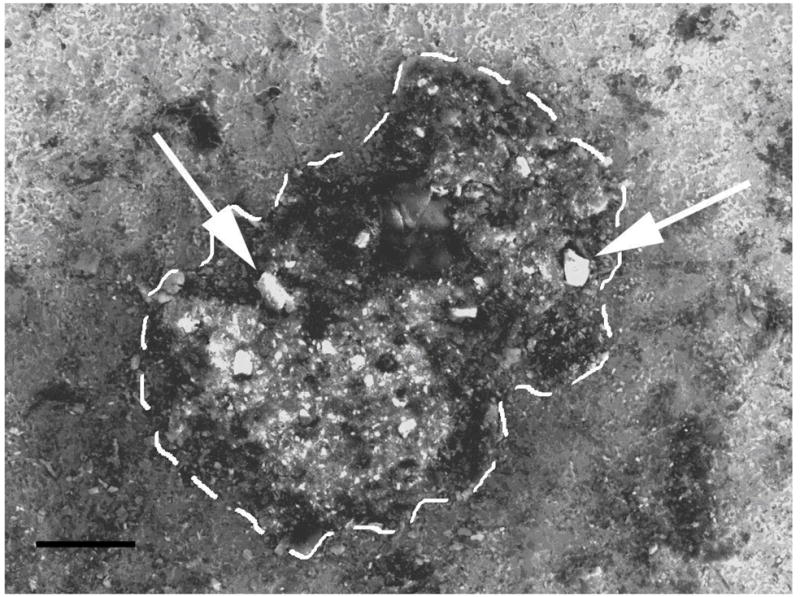

The presence of mineralized nodules was also noted by SEM (Figure 5), and confirmed with XEDA (Table 1), showing roughly 40 times the calcium concentration and 8 times the phosphate concentration in the nodule as compared to adjacent titanium surfaces where nodules were not present.

Figure 5.

SEM photograph of a nodule present on phosphated titanium surface (500x mag.). Nodule outlined by white dashes. Mineralization is taking place on the nodule surface (arrows). Bar = 100 μm

Table 1.

XEDA Analysis of Nodule Mineral Content Compared to Non-Nodule Area of Disc

| Element | Nodule | PT Surface | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | 4.13% | 0.10% | 41x |

| P | 7.19% | 0.90% | 8x |

| Ti | 75.41% | 88.17% | No change |

| Al | 8.59% | 7.32% | No change |

| V | 4.68% | 3.51% | No change |

Atomic percentages of elements present on forming nodule and on adjacent phosphated titanium (PT) surface where no nodules were present.

TGF-β1 and IL-1β ELISAs

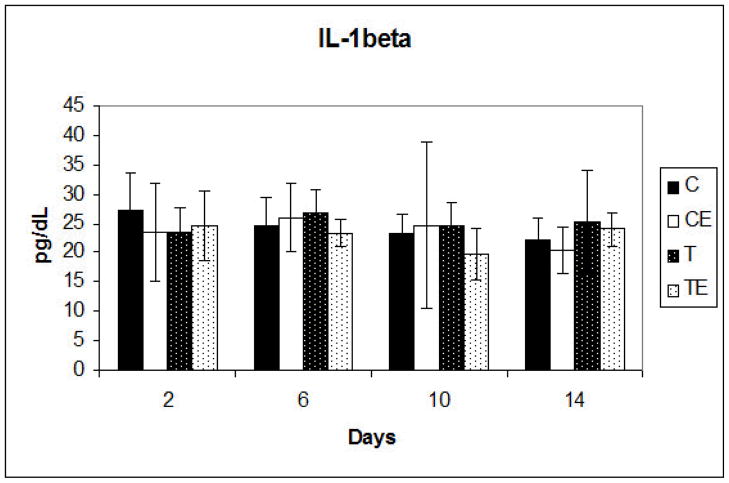

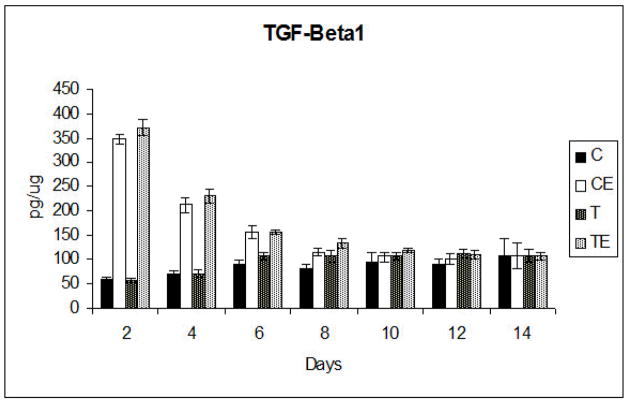

IL-1β ELISA analysis at days 2, 6, 10 and 14 revealed no significant differences between any of the groups and no significant changes over time (Figure 6). TGF-β1 ELISA analysis was done at days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14. On days 2, 4 and 6 significantly (p<0.001) increased TGF-β1 production in the EMD treated phosphate and non-phosphate groups was noted when compared to the non-EMD treated phosphate and non-phosphate groups. In both the phosphate and non-phosphate EMD treated groups, the TGF-β1 levels were highest at 2 days in culture, and then progressively declined until there was no significant difference at day 10 for all groups (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Mean IL-1β production ± standard deviation at days 2,6,10 & 14. No significant differences were detected between any of the groups. C, Non-phosphated titanium; CE, non- phosphated titanium plus EMD, T, Phosphated titanium; TE, Phosphated titanium plus EMD

Figure 7.

Mean TGF-β1 production ± standard deviation. Significant differences were detected between the EMD (E) groups and the non EMD groups up to day 8. After Day 8, there were no significant differences between any of the groups. C, Non-phosphated titanium; CE, non-phosphated titanium plus EMD, T, Phosphated titanium; TE, Phosphated titanium plus EMD

TGF-β1 production was not significantly different between the phosphate plus EMD and non-phosphate plus EMD groups, although the phosphate plus EMD group produced more TGF-β1 at days 2, 4, 8, 10 and 12. In the absence of EMD, the phosphate group produced more TGF-β1 than the non-phosphate group, except on day 2, but these differences were not significant prior to day 8. At day 8, a significant increase in Tgf-ß1 production was noted in the phosphate and phosphate plus EMD groups (p<0.001), compared to the non-phosphate and non-phosphate plus EMD groups. No significant differences were detected after 8 days between the phosphated and non-phosphated titanium groups.

From day 2 to day 14, there was a steady decline in TGF-β1 production by osteoblasts in the EMD groups and a slight but non-significant increase of TGF-β1 production by osteoblasts in the non-EMD groups. Control wells of phosphated and non-phosphated control titanium discs cultured with EMD and without cells, showed no TGF-β1 expression at any time.

DISCUSSION

Titanium implants are becoming the standard of care in replacing missing teeth and stabilizing dentures. Newer titanium implant surfaces accelerate osseointegration, which shortens the healing phase after surgical implant placement. Phosphated titanium is gaining increased interest in the implant literature. Viornery and associates (35) evaluated rat osteoblasts grown on phosphoric-acid-modified titanium for up to 8 days, with the phosphate covalently bonded to the titanium. They found no differences in the proliferation of osteoblasts on these surfaces compared to controls, showing that the phosphated surfaces where not cytotoxic to the osteoblasts. They also reported that the modified titanium surfaces had significantly more synthesized total protein and collagen type I than the unmodified titanium. The authors concluded that the covalently bonded phosphate might form a scaffold for new bone formation, which ultimately will lead to bonding of the implant to the host tissue (35).

A longer-term study was done by Urban and associates (7) who looked at electrolytic phosphate coated implants placed in a dog humeral model for up to 6 months. While evaluating pull out strength and the tissue interface, they found no significant difference between the phosphate coated implants and the pure titanium implants, but they did find significantly enhanced implant contact with bone and marrow and decreased fibrous tissue interface in the phosphate group. The electrolytic phosphated titanium surface used by Urban and associates in their study is the same as that used in the present study.

Nodules are created by osteoblasts once they reach confluence in tissue culture. Cells clump together in layers to form the nodules, and then begin forming an osteoid-like matrix, which they then mineralize. Mineralization of nodule matrix usually requires the presence of a mineralizing medium containing an inorganic source of phosphate, such as β-glycerophosphate. Osteoblasts formed nodules of various sizes in all treatment and control groups. The presence of nodules even in the absence of mineralizing media is likely due to the presence of ascorbic acid in the culture medium. The absence of mineralization of nodules noted in the non-phosphate group occurred even in the presence of ascorbic acid, indicating that ascorbic acid without a source of phosphate will not result in mineralization.

In the present study it was found that mineralization of nodules occurred in the phosphated titanium group when mineralizing medium was not added. However, no mineralization of nodules occurred on the control, non-phosphated surface in the absence of mineralizing medium. This finding suggests that the phosphate treatment of the titanium induced osteoblast differentiation similar to that seen with mineralizing medium. Nodule size and number was not different among the groups and EMD did not appear to affect mineralization. The limited number of sections for analysis warrants caution in data interpretation and points to the need for future studies to evaluate nodule formation and subsequent mineralization on the phosphated titanium surface, and these studies are currently being planned.

The cytokine TGF-β1 was evaluated in this study because of its role in the regulation of bone growth and healing, and its wide recognition by an array of cells in the body. TGF- β1 is part of the TGF multifunctional polypeptide growth factor family involved in embryogenesis, inflammation, regulation of immune response, angiogenesis, wound healing and extracellular matrix formation (22,38,39). In this study, TGF-β1 was produced by osteoblasts in all groups, and EMD significantly increased initial TGF-β1 production by osteoblasts on both phosphated and non-phosphated titanium surfaces. However, Tgf-ß1 production declined rapidly over time in these groups. The transient nature of the EMD-initiated TGF-β1 boost supports evidence for an early role for EMD similar to its early role in early wound healing. The fact that EMD stimulated cells to produce TGF-β1 is consistent with findings from other studies. Okubo and associates (36) evaluated the effects of EMD on human periodontal ligament (PDL) cells and they found that EMD had no appreciable effect on osteoblastic differentiation, but it did stimulate cell growth and IGF-I and TGF-β1 production. Lyngstadaas and associates (37) also evaluated EMD effects on human PDL cells and found that the cellular interaction with EMD generated an intracellular cAMP signal, after which cells secreted TGF-β1, IL-6 and PDGF.

The present study also addressed the question of whether EMD contained endogenous TGF-β1 that could be released into the culture media in the absence of cells and it was found that no TGF-β1 was measured in the absence of cells. Therefore, the TGF-β1 did not come from the EMD, rather the EMD stimulated TGF-β1 production by the osteoblasts. Gestrelius and associates (40) found similar results, in that ELISA analysis of EMD showed that GM-CSF, calbindin D, EGF, fibronectin, bFGF, gamma-interferon, IL-1β, 2,3,6, IGF-1, IGF-2, NGF, PDGF, TNF and TGF-β were not present in culture medium.

The role that EMD has in implant osseointegration is still not clear. Schwarz and associates (41) evaluated human osteoblasts on SBAE titanium with the addition of varying amounts of EMD. EMD at low concentrations increased cell viability similar to the non-EMD groups, while high concentrations resulted in statistically significant increases in cell viability than the controls (41). In a dog study, Casati and associates (31) looked at periodontal regeneration around implants. They looked at EMD, guided bone regeneration (GBR), EMD plus GBR or control. They found that EMD alone had no statistically significant effect, but EMD plus GBR was more advantageous than any other treatment. In another study by Shimizu-Ishiura and associates (30), titanium implants were placed into rat femurs with EMD or a control carrier. They found that at 14 and 30 days post-implantation the EMD group had trabecular bone areas significantly greater than the control. Contrary to this, Franke Stenport and associates (32) also evaluated titanium implants in rat femurs with the addition of EMD. They found no beneficial effects from the EMD treatment on bone formation around titanium implants. However, they did find the control group demonstrated significantly higher removal torque and sheer force (32). The data reported here does not indicate an added advantage of EMD to the rate of mineralization, but does provide increased Tgf-ß1, which may facilitate the increased cell viability noted by Schwarz et al. (41).

IL-1β was evaluated in this study due to its role in exacerbating chronic inflammation and diseases. IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine whose activity is suppressed by TGF-β1 (9, 25), and its production by osteoblasts could be an indicator of cellular cytotoxicity. The fact that there were no significant differences in IL-1ß production between any of the groups, and no significant differences at any time periods is important because an increase in IL-1β would indicate an adverse reaction by the osteoblasts. These data indicate that the treated titanium surfaces are not cytotoxic, and are therefore potentially useful for increasing osteoblast function.

In conclusion, results from this study show that electrolytic phosphated titanium is biocompatible with osteoblasts similar to non-phosphated titanium. The increased TGF-β1 production and nodule calcification caused by the phosphated titanium indicates that the phosphating process has the potential to accelerate implant osseointegration. EMD initiated early TGF-β1 production, but did not accelerate or initiate mineralization without the presence of phosphate, so it is unclear whether the addition of EMD is advantageous to osteoblast function in contact with titanium. Future studies are needed to evaluate the long term effects on bone formation of phosphated titanium surfaces and the role EMD has to play in facilitating this process.

Acknowledgments

Support for this project was received from Baylor College of Dentistry, from Straumann, Inc. and NIH grant DEO15893-01 to Lynntech Inc.

References

- 1.Karoussis IK, Salvi GE, Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Hammerle CHF, Lang NP. Long- term implant prognosis in patients with and without a history of chronic periodontitis: a 10-year prospective cohort study of the ITI dental implant system. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2003;14:329–339. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.000.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Bruyn H, Collaert B. The effect of smoking on early implant failure. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:260–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bain CA. Smoking and implant failure –benefits of a smoking cessation protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1996;11:756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson JW, Shernoff AF, Tarlow JL, Colwell JA, Scheetz JP, Bingham SF. Dental endosseous implant assessments in type 2 diabetic population: a prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2000;15:811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris HF, Ochi S, Winkler S. Implant survival in patients with type 2 diabetes: placement up to 36 months. Ann Periodontal. 2000;5:157–165. doi: 10.1902/annals.2000.5.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guizzardi S, Galli C, Martini D, Belletti S, Tinti A, Raspanti M, Taddei P, Ruggeri A, Scandroglio R. Different titanium surface treatment influences human mandibular osteoblast response. J Periodontol. 2004;75:273–282. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson CJ, Minevski ZS, Urban RM, Turner TM, Jacobs JJ. Corrosion and wear resistant bioactive surgical implants. Proceedings from ASM Materials and Processes for Medical Devices Conference; Anaheim, Ca. September 8–10, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marieb EN. Human anatomy and physiology. In: Heyden R, Schmid J, Schaefer EM, editors. Bones and Bone tissue. 3. California: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc; 1995. pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park YG, Kang SK, Kim WJ, Lee YC, Kim CH. Effects of TGF-beta, TNF-alpha, IL-beta and IL-6 alone or in combination, and tyrosine kinase inhibitor on cyclooxygenase expression, prostaglandin E2 production and bone resorption in mouse calvarial bone cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:2270–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokoro Y, Yamamoto T, Hara K. IL-1β mRNA as the predominant inflammatory cytokine transcript: correlation with inflammatory cell infiltration into human gingiva. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stashenko P, Fujiyoshi P, Obernesser MS, Prostak L, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Levels of IL-1β in tissue from sites of active periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:548–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai CC, Ho YP, Chen CC. Levels of IL-1β and IL-8 in gingival crevicular fluids in adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1995;66:852–859. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.10.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao RT, Curtis DA, Richards DW, Preble J. Increased IL-1β in the crevicular fluid of diseased implants. Int J Oral & Maxillofac Implants. 1995;10:696–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panagakos FS, Aboyoussef H, Dondero R, Jandinski JJ. Detection and measurement of inflammatory cytokines in implant crevicular fluid: a pilot study. Int J Oral & Maxillofac Implants. 1996;11:794–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis DA, Kao R, Plesh O, Finzen F, Franz L. Crevicular fluid analysis around two dialing dental implants: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;6:210–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849x.1997.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauschka PV, Mavrakos AE, Iafrati M, Doleman SE, Klagsbrun M. Growth factors in bone matrix: Isolation of multiple layers of bone types by affinity chromatography on heparin sepharose. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12665–12674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robey PG, Young MF, Flanders KC, Roche NS, Kondiaah P, Reddi AH, Termine JD, Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Osteoblasts synthesize and respond to transforming growth factor-type beta. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:457–463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chenu C, Pfeilschifter J, Mundy GR, Roodman GD. Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits formation of osteoclast-like cells in long-term human marrow studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:5683–5687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen DM, Stempien SA, Thompson AY, Seyedin SM. Transforming growth factor-beta modulates the expression of osteoblast and chondroblast phenotypes in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1988;134:337–346. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041340304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinar DM, Rodan G. Biophasic effects of transforming growth factor-beta on the production of osteoclast-like cells in mouse bone marrow cultures: the role of prostaglandins in the generation of these. Endocrinology. 1990;126:3153–3158. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-6-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strong DD, Beacher AL, Wergedal JE, Linkhart TA. Insulin-like growth factor II and transforming growth factor-beta regulate collagen expression in human osteoblast-like cells in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:15–23. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skaleric U, Kramar B, Petelin M, Pavica Z, Wahl SM. Changes in TGF-β1 levels in gingival crevicular fluid and serum associated with periodontal inflammation associated in humans and dogs. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:136–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trasatti C, Spears R, Gutmann JL, Opperman LA. Increased Tgf-β1 production by rat osteoblasts in the presence of Pepgen P-15 in vitro. J Endodon. 2004;30:213–217. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oreffo RO, Mundy GR, Seyedin SM, Bonewald L. Activation of the bone-derived latent TGF-ß complex by isolated osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;158:817–23. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92795-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espevik T, Figari IS, Shalaby R, Lackides GA, Lewis GD, Shepard HM, Palladino MA. Inhibition of cytokine production by cyclosporine A and transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 1987;166:571–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammarstrom L, Heijl L, Gestrelius S. Periodontal regeneration in a buccal dehiscence model in monkeys after application of enamel matrix proteins. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:669–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sculean A, Donos N, Blaes A, Lauermann M, Reich E, Brecx M. Comparison of enamel matrix proteins and bioabsorbable membranes in the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects. A split mouth study. J Periodontol. 1999;70:255–262. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heijl L. Periodontal regeneration with enamel matrix derivative in one human experimental defect. A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:693–696. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1997.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizutani S, Tsuboi T, Tazoe M, Koshihara Y, Goto S, Togari A. Involvement of FGF-2 in the action of Emdogain® on normal human osteoblast activity. Oral Dis. 2003;9:210–217. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.02876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu-Ishiura M, Tanaka S, Lee WS, Debari K, Sasaki T. Effects of enamel matrix derivative to titanium implantation in rat femurs. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:269–276. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casati M, Sallum E, Nociti F, Caffesse R, Sallum A. Enamel matrix derivative and bone healing after guided tissue regeneration in dehiscence-type defects around implants. A histomorphometric study in dogs. J Periodontol. 2002;73:789–796. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franke Stenport V, Johansson CB. Enamel matrix derivative and titanium implants. An experimental pilot study in the rabbit. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:359–363. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams DC, Boder GB, Toomey RE, Paul DC, Hillman CC, Jr, King KL, et al. Mineralization and metabolic response in serially passaged adult rat bone cells. Calcified Tissue International. 1980;30:233–246. doi: 10.1007/BF02408633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr Al, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phnol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viornery C, Guenther HL, Aronsson BO, Péchy P, Descouts P, Grätzel M. Osteoblast culture on polished titanium disks modified with phosphonic acids. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:149–155. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okubo K, Kobayashi M, Takiguchi T, Takada T, Ohazama A, Okamatsu Y, et al. Participation of endogenous IGF-I and TGF-β1 with enamel matrix derivative-stimulated cell growth in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodont Res. 2003;38:1–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2003.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyngstadaas SP, Lundberg E, Ekdahl H, Andersson C, Gestrelius S. Autocrine growth factors in humal periodontal ligament cells cultured on enamel matrix derivative. J Clin Periodontal. 2001;28:181–188. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028002181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siato H, Tsujitani S, Oka S, Kondo A, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, Kaibara N. The expression of TGF-β1 is significantly correlated with the expression of VEGF and poor prognosis of patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:1455–1462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991015)86:8<1455::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cornelini R, Rubini C, Fioroni M, Favero GA, Strocchi R, Piattelli A. TGF-β1 expression in the peri-implant soft tissues of healthy and failing dental implants. J Periodontol. 2003;74:446–450. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gestrelius S, Andersson C, Linström D, Hammarström L, Somerman M. In vitro studies on periodontal ligament cells and enamel matrix derivative. J Clin Periodontal. 1997;24:685–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarz F, Rothamel D, Herten M, Sculean A, Scherbaum W, Becker J. Effect of enamel matrix derivative on the attachment, proliferation, and viability of human SaOs2 osteoblasts on titanium implants. Clin Oral Invest. 2004;8:165–171. doi: 10.1007/s00784-004-0259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]