Abstract

Near infrared (NIR) irradiation can penetrate up to 10 cm deep into tissues and be remotely applied with high spatial and temporal precision. Despite its potential for various medical and biological applications, there is a dearth of biomaterials that are responsive at this wavelength region. Herein we report a polymeric material that is able to disassemble in response to biologically benign levels of NIR irradiation upon two-photon absorption. The design relies on the photolysis of the multiple pendant 4-bromo7-hydroxycoumarin protecting groups to trigger a cascade of cyclization and rearrangement reactions leading to the degradation of the polymer backbone. The new material undergoes a 50% Mw loss after 25 sec of ultraviolet (UV) irradiation by single photon absorption and 21 min of NIR irradiation via two-photon absorption. Most importantly, even NIR irradiation at biologically benign laser power is sufficient to cause significant polymer disassembly. Furthermore, this material is well tolerated by cells both before and after degradation. These results demonstrate for the first time a NIR sensitive material with potential to be used for in vivo applications.

INTRODUCTION

Smart polymeric materials are presently one of the main focuses in biomedical materials research. These types of materials respond to subtle environmental changes in a controlled, predictable way, which makes them useful tools for tissue engineering1–10, implants1,11–14 and wound healing15, drug delivery9,16–19 and biosensors20–25. Various internal and external triggers, such as pH26–29, specific enzymes30–36, temperature4,37–41, ultrasound42–44, magnetic field17,45–46 and light18,45,47–56 are being explored. Optical stimulus is especially attractive as it can be remotely applied for a short period of time with high spatial and temporal precision. A large number of light-degradable materials (micelles,57–58 polymeric nanoparticles59 and bulk hydrogels60–61) have been reported recently. However, most of the materials reported respond to NIR light by undergoing a hydrophobicity switch62–65 and the photodegradation products are high molecular weight linear or crosslinked polymer fragments that may be difficult to clear from the body. Additionally, most of the reported light-degradable materials respond efficiently to UV irradiation. Near infrared (NIR) light can penetrate up to 10 cm deep into tissue66 with less damage and absorption or scattering and is more desirable for in vivo applications67–69. Despite these advantages, only a handful of organic materials reported to date can respond to high power NIR light due to the inefficient two photon absorption process. None are able to respond to low power NIR light which is important to biological applications because it causes less photodamage to tissue and cells.70 For in vivo applications, it would be more advantageous to have a material that degrades into small fragments upon NIR light exposure, which can then be easily excreted, with less long term risks. Therefore, we designed a linear synthetic polymer with multiple pendant light-sensitive triggering groups in such a way that once these groups are cleaved, a cascade of cyclization and rearrangement reactions is triggered, leading to backbone degradation48. The first proof – of – concept polymer utilized a commercially available and well-studied o-nitrobenzyl (ONB) triggering group, which was attached to the polymer backbone via a diamine linker. ONB groups are widely used in synthetic chemistry as protecting groups for alcohols and amines, which can be readily removed with UV light. They were also shown to photolyze upon NIR irradiation via two-photon excitation, although their two-photon uncaging cross-sections (a quantitative measure of the efficiency of a molecule to simultaneously absorb two photons of light and convert that energy into a chemical reaction) are very low71. Consequently, several hours of continuous NIR irradiation at high laser power were required to trigger the polymer degradation. Another drawback of the ONB triggering group is potential toxicity of nitrosobenzaldehyde, the product of photocleavage of ONB groups. Clearly, the reported polymer required further modification in order to become a practically useful material. The material we are reporting here utilizes another well-known photocleavable group, 4-bromo7-hydroxycoumarin (Bhc), which has a much higher two-photon uncaging cross-section72–74, and produces no toxic byproducts upon cleavage. Introduction of the new triggering group drastically increases the sensitivity of the material to NIR light, reducing the exposure time required to produce appreciable polymer degradation to a few minutes. Moreover, we show that laser power as low as 200 mW is sufficient to trigger polymer fragmentation. To our knowledge, this is the only polymeric material specifically designed to disassemble into small fragments in response to biologically benign levels of NIR irradiation.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Methods and Instrumentation

2,6-Bis-(hydroxymethyl)-p-cresol and 4-bromoresorcinol were purchased from Acros Organics and used as received. 4,5-Dimethoxy-2-nitrobenzyl alcohol and N,N-dimethylethylenediamine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Amberlyst 15 (dry resin) was purchased from Supelco. Adipoyl chloride was purchased from Aldrich and purified by vacuum distillation. All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere. Flash chromatography was performed using a CombiFlash Companion system. 1H NMR spectra were acquired using a Joel 500MHz spectrometer or a Varian 400MHz spectrometer. 13C NMR spectra were acquired using a Varian spectrometer operated at 100 MHz. UV spectra were collected using a Shimadzu UV-3600 UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer. Degradation of the monomers containing Bhc and ONB triggering groups (designated BhcM and ONBM) was monitored by an Agilent 1200 HPLC equipped with PDA and MSD detectors and a C18 column with 0.1% formic acid/H2O and 0.1% formic acid/acetonitrile as eluents at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The molecular weights of the polymers, BhcP and ONBP (where P denotes polymer), were measured relative to polystyrene standards using a Waters e2196 Series HPLC system equipped with RI and PDA detectors and a Waters Styragel HR 2 size-exclusion column with 0.1% LiBr/DMF as eluent and flow rate of 1mL/min at 37°C. For irradiation with UV light, a Luzchem LZC-ORG photoreactor equipped with 8 UV-A lamps (350 nm maximum intensity, 8 W) was used. A Ti:Sapphire laser (Mai Tai HP, Spectra Physics) with ~100 fs pulse widths and 80 MHz repetition rate generated light for NIR irradiation. For monomer and polymer degradation by NIR, 2.5 W (4 kW/cm2) of 750 nm (for ONBM and ONBP) and 740 nm (for BhcM and BhcP) light was focused into the solution using a EFL 33.0 mm lens. Low power irradiation experiments used 200 mW (0.32 kW/cm2) of 740 nm light (2.5 nJ/pulse for the laser repetition rate) attenuated with a wave plate/polarizer combination.

Compounds 2 and 3 were synthesized according to a previously published procedure75. Compound 9 was synthesized according to a previously published procedure74. Compounds 4 and 10 were synthesized according to a previously published procedure73. Their 1H NMR spectra were in agreement with the published data and the experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information. The synthesis of ONBM and ONBP is described in a previous publication48.

Compound 5

Compound 3 (0.5 g, 0.89 mmol) in 10 mL DCM was added dropwise over 30 min to a solution of N,N-dimethylethylenediamine in 15 mL DCM and 5 mL DMF at 0°C. After 30 min the solvents and excess of N,N-dimethylethylenediamine were removed on rotovap and reaction mixture was dissolved in 4 mL of dry DMF and Et3N (0.8 mL) and compound 4 were added. The reaction was stirred at RT for 1h, after that the solvents were removed on rotovap and the residue was purified by flash-chromatography on cyano-modified silica gel with hexanes/ethyl acetate (100%/0% - 0%/100%) as eluent. Yield: 0.39g (51%).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.17 – 7.12 (m, 3H), 6. 31 (s, 1H), 5.31 (s, 2H), 5.28 – 5.25 (m, 2H), 4.63 – 4.58 (m, 4H), 3.62 – 3.53 (m, 4H), 3.51 (s, 3H), 3.61 – 3.00 (m, 6H), 2.32 (s, 3H), 0.9 (s, 18H), 0.06 (s, 12H) ppm.

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 160.38, 156.33, 155.17, 154.93, 154.26, 149.20, 143.20, 135.54, 133.43, 127.68, 115.60, 112.57, 106.66, 104.14, 95.25, 64.26, 62.56, 62.18, 60.57, 60.39, 56.82, 48.33, 47.29, 35.60, 26.04, 18.51, −5.13 ppm.

HRMS: measured mass: 873.2780; theoretical mass: 873.2784; composition: C39H59N2O10BrSi2Na

Compound 6

Compound 5 (0.11 g,) was dissolved 15 mL of MeOH and 2 mL of DCM, Amberlyst 15 was added and reaction was stirred at RT for 2 hours. The catalyst was filtered off, solvents were removed on rotovap and the residue was purified by flash-chromatography on silica gel with hexanes/ethyl acetate (70%/30% - 0%/100%). Yield: 0.059 g (74%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.73 – 7.67 (m, 1H), 7.18 – 7.04 (m, 3H), 6.36 – 6.26 (m, 1H), 5.30-5.24 (m, 4H), 4.51 – 4.43 (m, 4H), 3.69 – 3.56 (m, 4H), 3.51 (s, 3H), 3.20 – 3.03 (m, 6H), 2.31 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C (100 MHz, CDCl3): 160.84, 156.69, 154.14, 149.68, 145.04, 136.27, 133.22, 130.16, 127.69, 110.75, 109.57, 106.91, 104.05, 95.69, 95.21, 64.20, 62.38, 60.56, 56.81, 55.50, 46.94, 35.18, 20.94 ppm.

HRMS: theoretical mass: 645.1054; measured mass: 645.1050; composition: C27 H31 Br N2 O10 Na.

BhcM

Compound 6 (0.12g, 0.137 mmol) was dissolved in 1mL DCM, 1 mL TFA was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature and monitored by TLC (ethyl acetate/hexane = 7/3). After the reaction was completed, solvents were removed on high vacuum, and crude product was purified by flash-chromatography on silica gel with hexanes/ethyl acetate (70%/30% - 0%/100%). Yield: 0.05 g (61%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): 7.68-7.64 (m, 1H), 7.38-7.27 (m, 2H), 7.00-6.97 (m, 1H), 6.36-6.27 (m, 1H), 5.32-5.27 (m, 6H), 3.64-3.53 (m, 4H), 3.19-3.05 (m, 6H), 2.38-2.35 (m, 3H) ppm.

13C (100 MHz, DMSO): 159.71, 157.47, 154.97, 153.81, 150.75, 142.80, 134.47, 134.08, 128.50, 126.18, 110.51, 108.35, 106.23, 103.23, 62.03, 57.70, 46.60, 46.05, 35.06, 34.37, 33.81, 20.89 ppm.

HRMS: theoretical mass: 601.0787; measured mass: 601.0792; composition: C25 H27 Br N2 O9 Na.

BhcP

Monomer 6 (0.2 g, 0.32 mmol) and adipoyl chloride (0.046 mL, 0.32 mmol) were dissolved in 2 mL DCM under nitrogen, and pyridine (0.156 mL, 1.92 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture dropwise over 10 min. The polymerization was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was concentrated on a rotovap to 0.2 mL and precipitated into 5 mL of cold EtOH, yielding waxy polymer product 7. Compound 7 was dissolved in 0.5 mL DCM and 0.5 mL TFA was added. The solution was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The solvents were removed on rotovap. The oligomers were removed by repeated precipitation of the polymer solution in DCM into cold MeOH. Yield: 63% (white solid).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): 7.62 (s, 1H), 7.23 – 7.13 (m, 2H), 6.67 (s, 1H), 6.31 (s, 1H), 5.29 (s, 2H), 5.00 (s, 4H), 3.65 – 3.46 (m, 4H), 3.17 – 3.04 (m, 6H), 2.29 (s, 6H), 1.64 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C (100 MHz, DMSO): 159.60, 157.51, 153.75, 150.48, 145.01, 129.16, 128.30, 110.47, 108.41, 106.21, 103.16, 61.94, 60.74, 60.57, 35.00, 33.40, 33.29, 32.94, 24.04, 23.93, 23.78, 23.71, 20.61, 20.37 ppm.

UV and NIR degradation of ONBM and BhcM

Solutions of ONBM and BhcM in PBS pH 7.4 (1 mg/mL), with 4-hydroxy-benzoic acid-n-hexyl ester as an internal standard, were placed in quartz semi-micro spectrophotometer cells (10 mm path length) and irradiated with UV light for certain periods of time. For NIR irradiation experiments, the solutions of ONBM and BhcM were placed in 50 μL quartz cells with 3 mm path length and irradiated at 740 and 750 nm, respectively. The irradiated solutions were injected into HPLC and chromatograms at 280 nm were recorded. The fraction of the remaining caged compounds was calculated by integrating the peaks of ONBM and BhcM relative to the peak of the internal standard.

UV and NIR degradation of ONBP and BhcP

For UV degradation of the polymers, solutions of ONBP and BhcP (0.1 mg/mL) in a mixture of acetonitrile and PBS 7.6 (9:1 and 7:3, respectively) were placed into quartz semi-micro spectrophotometer cells (10 mm path length) and irradiated with UV light inside a photoreactor for certain periods of time. The irradiated solutions were incubated at 37°C for 96 hrs. The solvents were removed on vacuum. The organic residue was dissolved in DMF and injected into GPC. In the NIR irradiation experiments, for each data point three separate solutions containing ONBP or BhcP were irradiated for the given time and combined for incubation at 37°C followed by solvent removal and dissolution in DMF to achieve acceptable signal to noise ratio in GPC.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

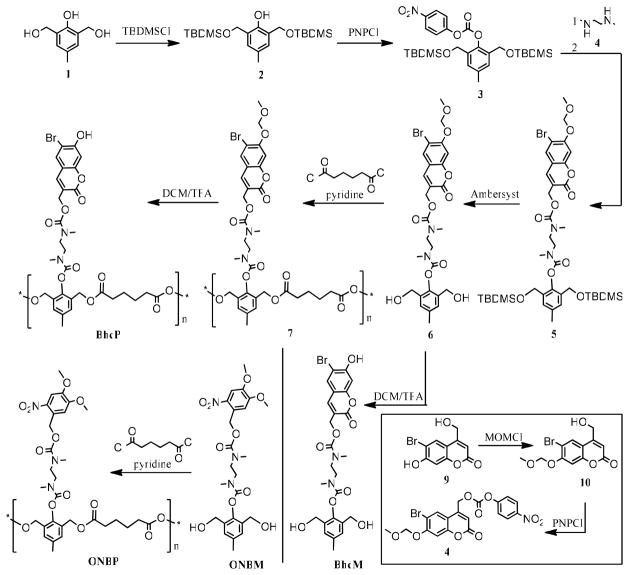

Synthesis of BhcM and BhcP

In order to install the 7-hydroxy-4-bromocoumarin triggering group we modified the previously published scheme for ONBP48 resulting in a synthetic route to BhcP shown in Scheme 1. We started with commercially available 2,6-bis-(hydroxymethyl)-p-cresol, 1, and selectively protected the benzylic alcohols with TBDMSCl in the presence of imidazole to obtain compound 2 in 87.5% yield. Activated carbonate 3 was obtained in 85% yield by reacting compound 2 with PNPCl in the presence of DMAP and Et3N in DCM. N,N,-Dimethylethylene diamine was reacted with compound 3 at a stoichiometric ratio of 3 to 1 to achieve conversion of only one amino group of the diamine into a carbamate. Excess N,N,-dimethylethylene diamine was removed and the coumarin derivative 4 was added into the reaction mixture to obtain compound 5 in 51% yield. The TBDMS protecting groups were removed with Amberlyst-15 (74% yield). Monomer 6 was copolymerized with adipoyl chloride in DCM in the presence of pyridine to afford polymer 7. Finally, the MOM protective groups were removed in DCM/TFA solution to afford the final polymer, BhcP. Low molecular weight oligomers were removed by precipitating the polymer into ice-cold MeOH. The combined yield of BhcP after the polymerization and deprotection steps was 63%. The molecular weight (Mw) of BhcP was determined by GPC to be 31,500 Da (PDI = 1.09) relative to PS standards.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route to BhcM and BhcP and the structures of ONBM and ONBP.

BhcM was obtained in 61% from compound 6 by removing the MOM protective group in a mixture of TFA and DCM.

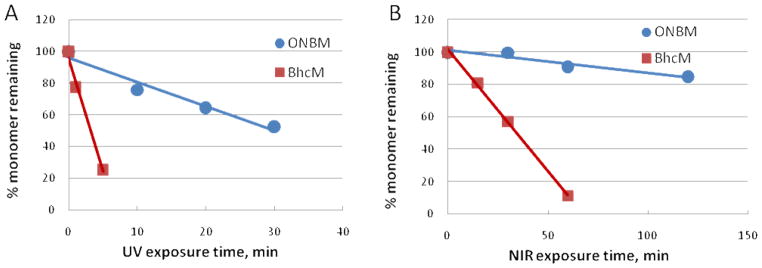

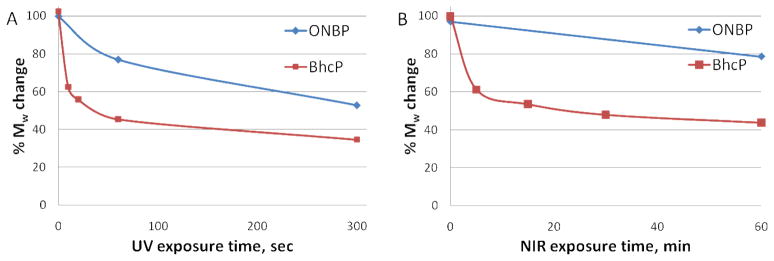

Degradation of ONBM and BhcM

To compare the rates of cleavage of the ONB and Bhc triggering groups, solutions of ONBM and BhcM were first exposed to 350 nm light for certain time periods and injected into the HPLC. The formation of nitrosobenzaldehyde and 4-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin confirmed the photolysis of ONBM and BhcM. Figure 1A shows the percentage of remaining monomer, calculated relative to an internal standard, as a function of UV exposure time for ONBM and BhcM. The rate of photolysis of BhcM was 10 times higher compared to ONBM, consistent with the previous reports of one-photon uncaging quantum yields of other alcohols and amines 72–74. Comparing the red and blue traces in Figure 1A, 50% of the Bhc groups were cleaved after 3.2 min of irradiation, while 30.18 min irradiation was required to cleave 50% of ONB groups. The same 10-fold difference in the rates of triggering group cleavage was observed upon NIR irradiation of the monomers. Figure 1B shows 50% of Bhc groups were cleaved after 34 min versus 370 min for ONB groups. The Bhc protecting group shows a higher two photon absorption due to the increased π-conjugation length which leads to a higher dipole moment induced by the electric field of a light wave.76 Additionally, the introduction of halogen atoms enhances intersystem crossing and therefore improves the photolysis quantum yield.74 Consequently, a large difference in the two-photon uncaging cross-sections of the two triggering groups could be expected. However, it is difficult to predict by how much the cleavage rate will change when switching from one caging group to the other, since the uncaging efficiency is affected by many factors, such as the structure of the leaving group, the solvent and the wavelength and the power of the laser used in the experiment. The reported two-photon uncaging of acetic acid by Bhc and ONB-protected esters at 740 nm was 1.99 GM and 0.03 GM, respectively (66-fold difference) and 0.42 GM and 0.01 GM at 800 nm (42-fold difference) 74. Uncaging of L-glutamic acid by Bhc ester was only 0.95 GM 74. It should also be mentioned that in our experiments the ONBM and BhcM were irradiated with 750 nm and 740 nm of light, respectively, to account for the difference in the two-photon absorption maxima of the two groups. However, given the very short pulse widths of our laser, this difference in wavelength is likely not a large factor in the differences between our degradation rates and previously reported uncaging cross-sections.

Figure 1.

Disappearance of ONBM and BhcM upon UV irradiation (A) and NIR (B) irradiation.

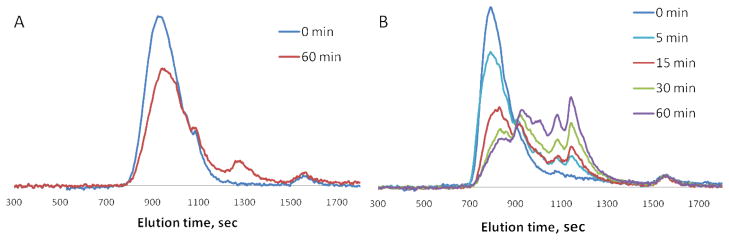

Degradation of ONBP and BhcP

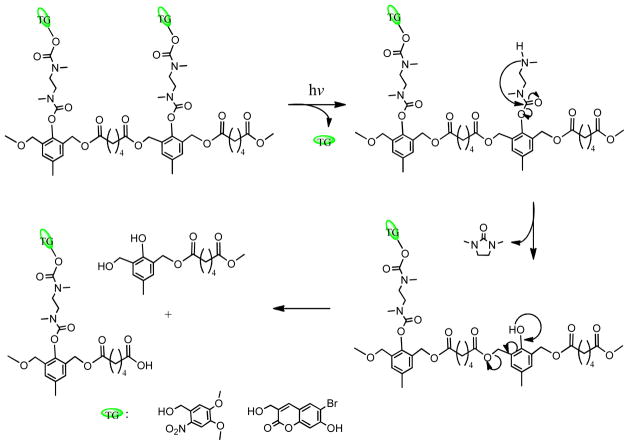

Scheme 2 shows the mechanism of degradation of light-sensitive polymers containing a quinone-methide self-immolative moiety 75,77–78. The degradation starts when a triggering group is cleaved upon irradiation with either UV or NIR light, releasing an amino group. N,N-Dimethylethylene diamine linker cyclizes, unmasking an unstable phenol. The quinone-methide rearrangement of the phenol results in the cleavage of the polymer backbone.

Scheme 2.

Degradation mechanism of a light-sensitive polymer incorporating a quinone-methide moiety. TG = triggering group

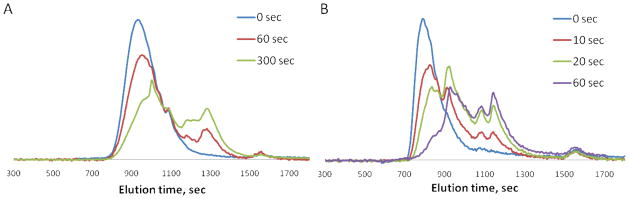

Degradation of the polymers containing ONB and Bhc triggering groups was studied in acetonitrile: PBS pH 7.6 (9:1 and 7:3, respectively). These combinations of solvents were found suitable to fully dissolve the polymers. The solutions were irradiated with UV light for 0, 10, 20, 60 and 300 sec, incubated at 37°C for 96 hrs and analyzed by GPC. As we have shown previously for ONBP,48 the polymer degradation is complete in 4 days in neutral pH. The chromatograms of ONBP and BhcP after UV exposure are shown in Figure 2. For both polymers, the GPC traces shift to longer elution times after irradiation and shorter fragments are formed. However, much shorter irradiation times are required to produce a significant reduction in the molecular weight of BhcP compared to ONBP. Plotting the percent change in the molecular weight of the polymers as a function of irradiation time (Figure 3A) reveals that BhcP degrades 10 times faster than ONBP, as could be expected from the monomers’ degradation rates. Thus, Mw of BhcP decreases by 50% after 25 sec of UV irradiation compared to 300 sec in the case of ONBP. In the control experiment, the solutions of ONBP and BhcP not exposed to UV or NIR irradiation were incubated at 37°C for 96 hrs. The molecular weights of the polymers remained unchanged, demonstrating that backbone fragmentation is controlled exclusively by the removal of the triggering groups and no dark hydrolysis takes place during this time.

Figure 2.

GPC chromatograms of ONBP (A) and BhcP (B) after UV exposure for 0, 10, 20, 60 or 300 sec and incubation at 37°C for 96 hrs.

Figure 3.

Decrease of the Mw of ONBP and BhcP as a function of exposure time to UV light (A) and NIR light (B).

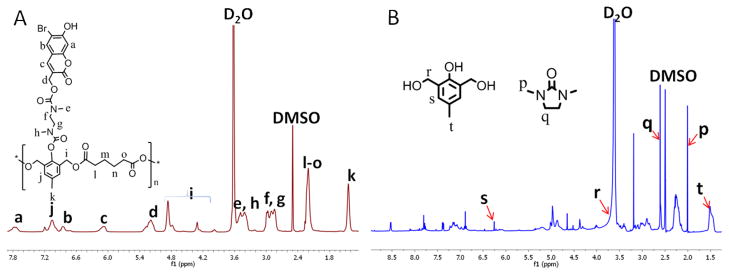

In order to confirm the degradation mechanism of BhcP, the polymer was exposed to UV irradiation in DMSOd6: D2O (6:1) and incubated for 72h at 37°C. The expected degradation products, 2,6-bis-(hydroxymethyl)-p-cresol and 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone, were identified in the 1H NMR spectrum of the partially degraded BhcP (Figure 4). The methyl group of cresol (t) appears at 1.52 ppm, shifted downfield compared to the methyl groups of cresol incorporated into the polymer (k, 1.44 ppm). The aromatic protons (s) appear as a sharp singlet at 6.26 ppm. The signal from the benzylic protons (r) is obscured by the signal from D2O. The signals of 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone appear very distinctly at 2.01 and 2.61 ppm. The peak assignments were confirmed by taking the spectra of the pure 2,6-bis-(hydroxymethyl)-p-cresol and 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone in DMSOd6: D2O (6:1).

Figure 4.

1H NMR spectra of BhcP in DMSOd6: D2O (6:1) before (A) and after (B) UV exposure.

Having confirmed that BhcP degrades in the way it was designed to, we moved to the degradation experiments using NIR light. The polymer was irradiated for 5, 15, 30 and 60 min and incubated for 96 h at 37°C. The GPC chromatograms after 96h of incubation are shown in Figure 5. Similar to UV irradiation, a significant drop in the intensity of the high molecular weight peak and appearance of the low molecular weight fragments were observed. In comparison with ONBP, much shorter irradiation times were required to produce significant fragmentation of BhcP. Figure 2B shows 50% molecular weight loss was achieved after 21 min of NIR irradiation of BhcP, while for ONBP one hour of continuous irradiation only resulted in 20% weight loss. Attempted irradiation of ONBP for more than 60 min to achieve 50% molecular weight loss resulted in evaporation of acetonitrile, which caused precipitation of ONBP from solution. Nevertheless, comparison of the degradation profiles of ONBP and BhcP after 60 min of irradiation confirms significantly improved NIR sensitivity of the polymer containing the Bhc triggering group.

Figure 5.

GPC chromatograms of ONBP (A) and BhcP (B) after exposure to NIR for 0, 5, 15, 30 or 60 min and incubation at 37°C for 96 hrs.

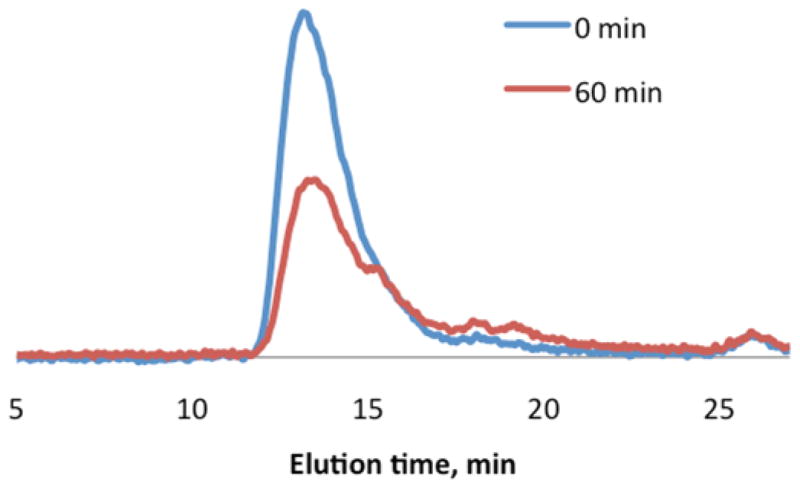

Even though NIR irradiation is considered more benign than UV wavelengths, there is a certain energy threshold above which photodamage will occur. Watanabe et al demonstrated that laser energies between 2 nJ/pulse and 4 nJ/pulse did not produce any damage to living cells70. Therefore, we attempted NIR light degradation of BhcP within this range (200 mW, corresponding to 2.5 nJ/pulse) to further demonstrate the practicality of using this material for in vivo applications. Exposure of the BhcP solution to low power NIR irradiation for 60 min resulted in the 29% drop in the molecular weight (Figure 6). This further illustrates the improvement achieved by using Bhc instead of ONB as a triggering group considering that after an hour of irradiation of ONBP at full laser power there was only a 20% decrease in molecular weight of the polymer. Furthermore, this experiment confirms that the polymer degradation is caused by the two-photon absorption process and not simply by possible heat generated by the laser, since at 200 mW heat generation is less likely.79

Figure 6.

GPC chromatograms of BhcP after exposure to low energy NIR irradiation for 60 min and incubation at 37°C for 96 hrs.

We investigated the cytotoxicity of BhcP by incubating various concentrations of it with cells and monitoring the cellular metabolic activity via a MTT assay. Measurements taken before and after irradiation show that the polymer and its degradation products are well tolerated by cells (Figure S1).

It has been reported that absorption properties and photolysis quantum yields of coumarin triggering groups are strongly affected by the polarity and hydrophobicity of the medium. For example, the quantum yield of a Bhc-protected galactose derivative in 10 mM KMops, pH 7.2 containing 25% acetonitrile was two times lower than in 10 mM KMops, pH 7.2 containing 0.1% DMSO73. Therefore, we didn’t expect that BhcP would maintain its high light sensitivity in bulk, since in this case the polymer backbone would create a local hydrophobic environment. Therefore, we envision further applications of this material in hydrogel systems where unrestricted access of water will allow for high photolysis quantum yields.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a new polymeric material capable of triggered disassembly upon irradiation with biologically benign levels of NIR light was developed. This material disassembles via photocleavage of Bhc groups with unprecedented sensitivity to NIR light. A 29% decrease in Mw of BhcP was observed after irradiation with 200 mW NIR light. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a polymeric material capable of disassembly into small molecules in response to harmless levels of irradiation. Notably, cell toxicity assays reveal excellent tolerance of cells to this polymer before and after irradiation and subsequent disassembly. This system is an excellent first step, however, further studies are warranted to improve the sensitivity of polymeric materials to NIR. We are currently pursuing several synthetic and engineering strategies to this end.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH Directors New Innovator Award (1 DP2 OD006499-01), and King Abdul Aziz City of Science and Technology (KACST) for financially supporting this study.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: details for the synthesis of compounds 2, 3, 4, 9 and 10 and cytotoxicity experiments. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Barrere F, Mahmood TA, de Groot K, van Blitterswijk CA. Materials Science & Engineering R-Reports. 2008;59:38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blan NR, Birla RK. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2008;86A:195. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao Y, Li HB. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:512. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Silva RMP, Mano JF, Reis RL. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:577. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehrbar M, Rizzi SC, Hlushchuk R, Djonov V, Zisch AH, Hubbell JA, Weber FE, Lutolf MP. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3856. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galler KM, D’Souza RN. Regenerative Medicine. 2011;6:111. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giselbrecht S, Gietzelt T, Gottwald E, Trautmann C, Truckenmuller R, Weibezahn KF, Welle A. Biomedical Microdevices. 2006;8:191. doi: 10.1007/s10544-006-8174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mieszawska AJ, Kaplan DL. Bmc Biology. 2010;8 doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moroni L, De Wijn JR, Van Blitterswijk CA. Journal of Biomaterials Science-Polymer Edition. 2008;19:543. doi: 10.1163/156856208784089571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhakaran MP, Venugopal J, Kai D, Ramakrishna S. Materials Science & Engineering C-Materials for Biological Applications. 2011;31:503. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans AT, Chiravuri S, Gianchandani YB. Biomedical Microdevices. 2010;12:179. doi: 10.1007/s10544-009-9371-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano C, Chiesa R, Sandrini E, Cigada A, Giavaresi G, Fini M, Giardino R. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 2005;16:1221. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-4732-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayant RD, McShane MJ, Srivastava R. Int J Pharm. 2011;403:268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang QW, Mochalin VN, Neitzel I, Knoke IY, Han JJ, Klug CA, Zhou JG, Lelkes PI, Gogotsi Y. Biomaterials. 2011;32:87. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabolinski ML, Alvarez O, Auletta M, Mulder G, Parenteau NL. Biomaterials. 1996;17:311. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong CB, Wong KL, Lam MHW. Chem Mater. 2008;20:1353. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng SL, Zhang MY, Niu XZ, Wen WJ, Sheng P, Liu ZY, Shi J. Appl Phys Lett. 2008;92 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong CB, Lam MHW, Yu HX. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16:1759. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman AS, Stayton PS, Press O, Murthy N, Lackey CA, Cheung C, Black F, Campbell J, Fausto N, Kyriakides TR, Bornstein P. Polym Adv Technol. 2002;13:992. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duceppe N, Tabrizian M. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2010;7:1191. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2010.514604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gant RM, Hou YP, Grunlan MA, Cote GL. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2009;90A:695. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan B, Magenau A, Kilian KA, Ciampi S, Gaus K, Reece PJ, Gooding JJ. Faraday Discuss. 2011;149:301. doi: 10.1039/c005340f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Y, Xia F, Xu L, Li J, Yang WS, Jiang L. Langmuir. 2010;26:1024. doi: 10.1021/la9041452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin G, Chang S, Hao H, Tathireddy P, Orthner M, Magda J, Solzbacher F. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical. 2010;144:332. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2009.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song J, Cheng Q, Zhu SM, Stevens RC. Biomedical Microdevices. 2002;4:213. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murthy N, Xu MC, Schuck S, Kunisawa J, Shastri N, Frechet JMJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930644100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XM, Wang LS. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1929. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sankaranarayanan J, Mahmoud EA, Kim G, Morachis JM, Almutairi A. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5930. doi: 10.1021/nn100968e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang YQ, Chen DJ. Eur Polym J. 2007;43:4178. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Veronese FM, Schiavon O, Pasut G, Mendichi R, Andersson L, Tsirk A, Ford J, Wu GF, Kneller S, Davies J, Duncan R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:775. doi: 10.1021/bc040241m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saez JA, Escuder B, Miravet JF. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:2614. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vemula PK, Cruikshank GA, Karp JM, John G. Biomaterials. 2009;30:383. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khelfallah NS, Decher G, Mesini PJ. Biointerphases. 2007;2:131. doi: 10.1116/1.2799034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romberg B, Flesch FM, Hennink WE, Storm G. Int J Pharm. 2008;355:108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khelfallah NS, Decher G, Mesini PJ. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2006;27:1004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Igari Y, Kibat PG, Langer R. J Controlled Release. 1990;14:263. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian BS, Yang C. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2011;11:1871. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2011.3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eissa AM, Khosravi E. Eur Polym J. 2011;47:61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowik DWPM, Leunissen EHP, van den Heuvel M, Hansen MB, van Hest JCM. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:3394. doi: 10.1039/b914342b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao JA, Liu YL, Xu HP, Wang ZQ, Zhang X. Langmuir. 2010;26:9673. doi: 10.1021/la100256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collett J, Crawford A, Hatton PV, Geoghegan M, Rimmer S. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2007;4:117. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu XD, Liu QA, Wu JC, Zhang MM, Cao XH, Zhang S, Wang Q, Chen LM, Yi T. Chemistry-a European Journal. 2010;16:9099. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang JW, Xu JS, Xu RX. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1278. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng F, Mal A, Kabo M, Wang JC, Bar-Cohen Y. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117:2347. doi: 10.1121/1.1873372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu JM, Liu SY. Macromolecules. 2010;43:8315. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruiz-Hernandez E, Baeza A, Vallet-Regi M. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1259. doi: 10.1021/nn1029229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aznar E, Marcos MD, Martinez-Manez R, Sancenon F, Soto J, Amoros P, Guillem C. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6833. doi: 10.1021/ja810011p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fomina N, McFearin C, Sermsakdi M, Edigin O, Almutairi A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9540. doi: 10.1021/ja102595j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koo HY, Lee HJ, Kim JK, Choi WS. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:3932. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy CP, Brady C, Cowley JF, McGlinchey SM, McGoldrick N, Kinnear DJ, Andrews GP, Jones DS. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2010;7:605. doi: 10.1517/17425241003677731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffin DR, Patterson JT, Kasko AM. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:1012. doi: 10.1002/bit.22882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kasko AM, Wong DY. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;2:1669. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pastine SJ, Okawa D, Zettl A, Frechet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13586. doi: 10.1021/ja905378v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin QA, Liu GY, Ji JA. Journal of Polymer Science Part a-Polymer Chemistry. 2010;48:2855. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woodcock JW, Wright RAE, Jiang XG, O’Lenick TG, Zhao B. Soft Matter. 2010;6:3325. [Google Scholar]

- 56.You J, Zhang GD, Li C. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1033. doi: 10.1021/nn901181c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goodwin AP, Mynar JL, Ma YZ, Fleming GR, Frechet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9952. doi: 10.1021/ja0523035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang X, Lavender CA, Woodcock JW, Zhao B. Macromolecules. 2008;41:2632. [Google Scholar]

- 59.He J, Tong X, Zhao Y. Macromolecules. 2009;42:4845. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kloxin AM, Kasko AM, Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Science. 2009;324:59. doi: 10.1126/science.1169494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng K, Tomatsu I, van den Broek B, Cui C, Korobko AV, van Noort J, Meijer AH, Spaink HP, Kros A. Soft Matter. 2011;7:4881. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cui W, Lu X, Cui K, Wu J, Wei Y, Lu Q. Nanotechnology. 2011;22:065702. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/6/065702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Babin J, Pelletier M, Lepage M, Allard J-F, Morris D, Zhao Y. Angewandte Chemie. 2009;121:3379. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee H-i, Wu W, Oh JK, Mueller L, Sherwood G, Peteanu L, Kowalewski T, Matyjaszewski K. Angewandte Chemie. 2007;119:2505. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodwin AP, Mynar JL, Ma Y, Fleming GR, Frechet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9952. doi: 10.1021/ja0523035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weissleder R. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:316. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen CC, Lin YP, Wang CW, Tzeng HC, Wu CH, Chen YC, Chen CP, Chen LC, Wu YC. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3709. doi: 10.1021/ja0570180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braun GB, Pallaoro A, Wu GH, Missirlis D, Zasadzinski JA, Tirrell M, Reich NO. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2007. doi: 10.1021/nn900469q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raghavachari R, editor. Near-Infrared Applications in Biotechnology. New York: 2001. p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe W, Arakawa N, Matsunaga S, Higashi T, Fukui K, Isobe K, Itoh K. Optics Express. 2004;12:4203. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aujard I, Benbrahim C, Gouget M, Ruel O, Baudin JB, Neveu P, Jullien L. Chemistry-a European Journal. 2006;12:6865. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Furuta T, Watanabe T, Tanabe S, Sakyo J, Matsuba C. Org Lett. 2007;9:4717. doi: 10.1021/ol702106t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suzuki AZ, Watanabe T, Kawamoto M, Nishiyama K, Yamashita H, Ishii M, Iwamura M, Furuta T. Org Lett. 2003;5:4867. doi: 10.1021/ol0359362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Furuta T, Wang SSH, Dantzker JL, Dore TM, Bybee WJ, Callaway EM, Denk W, Tsien RY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amir RJ, Pessah N, Shamis M, Shabat D. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2003;42:4494. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denning RG, Pawlicki M, Collins HA, Anderson HL. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2009;48:3244. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sagi A, Weinstain R, Karton N, Shabat D. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5434. doi: 10.1021/ja801065d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weinstain R, Sagi A, Karton N, Shabat D. Chemistry-a European Journal. 2008;14:6857. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schonle A, Hell SW. Opt Lett. 1998;23:325. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.