Abstract

Infectious spondylodiscitis is an uncommon disease with increasing incidence that typically presents with abnormalities in two adjacent vertebral bodies and the intervening disk. We describe two cases that initially presented with imaging abnormalities in only a single vertebral body. Both patients had a history of lumbar back pain and elevated inflammatory markers, but the lack of classical spondylodiscitis imaging findings led to diagnostic delay and confusion. It is likely that the incidence of atypical presentations of spondy-lodiscitis will increase as the disease incidence increases and imaging is performed at an earlier stage. It is important to recognize the disease early because early diagnosis is the key to preventing serious complications like epidural abscess and spinal cord compression.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious spondylodiscitis or infectious spondylitis is an infectious process involving two vertebral bodies and the disk between them. The incidence of this disease is estimated to be around 0.4 to 2.4 per 100,000 per year and tends to increase with increasing age.1,2 Many authors expect these numbers to increase because of better diagnostic techniques, increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients, growing IV drug use in young people, increased use of intravenous access devices, and increasing prevalence of genitourinary surgery in the elderly.3,4 Accurate and timely diagnosis is important because a missed or delayed diagnosis of spondylodiscitis can potentially lead to the development of epidural abscess and spinal cord compression along with vertebral bone destruction and spinal instability.5

Hematogenous spread of septic emboli is generally accepted as the most common mechanism by which infection is seeded into the vertebrae.4,6-8 The most common source of infection is thought to be the urinary tract.4 Classically, pyogenic spondylodiscitis presents with lesions in two adjacent vertebral bodies and the corresponding intervertebral disk. This is thought to be due to the segmental nature of the supplying arteries that bifurcate to supply two adjacent vertebral bodies6,9 In children, the presence of vascular channels that directly feed the disk allows for direct hematogenous infectious seeding of the disk. In adults, the direct blood supply to the disk is reduced and thus disk infection usually arises via direct spread from the vertebral body after the end-plate has been destroyed.16 Rarely, spondylodiscitis may affect only a single vertebral body with or without disk involvement and this may lead to diagnostic confusion. In this scenario, metastatic disease and mycobacterial infection become more prominent in the differential diagnosis. Thus, awareness of the variability of imaging findings in spondylodiscitis is important in minimizing delays in diagnosis. Our purpose here is to report two cases of spondylodiscitis that presented with imaging abnormalities in only one vertebra.

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

A 10-year-old boy, who was previously healthy prior to experiencing lumbar back pain and fever for several days, presented to his primary care provider (PCP). He had no radicular pain and no lower extremity weakness. Vital signs were within normal limits but he did have a subjective history of fevers. The only positive physical examination finding was point tenderness in the lumbar spine. The PCP obtained conventional lumbar radiography and blood tests. Imaging was interpreted as negative but the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated at 42 mm/hr (normal: 0-15 mm/hr) and 4.1 mg/dL(normal: <0.5 mg/ dL), respectively. He did not have leukocytosis. Lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained (Figure 1) which showed a hypointense lesion in the L4 vertebral body on both T1- and T2-weighted images. This was initially thought to most likely represent a hemangioma. He was discharged on non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for analgesia and was to closely follow up with his PCP.

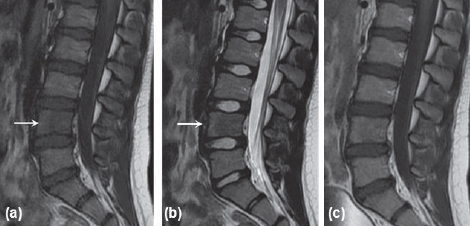

Figure 1.

Initial MRI for patient one. (a) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI showing hypointense lesion in L4 vertebral body. (b) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI with hypointense lesion in 14 vertebral body. (c) Sagittal T1-weighted post-gadolinium contrast MRI with fat suppression showing no enhancement.

Five days later the patient came to our emergency treatment center with worsening lumbar back pain not relieved by NSAIDs; he was admitted to our hospital for pain control. He underwent a lumbar spine CT which showed a subtle hypodensity in the L4 vertebral body (Figure 2). A repeat MRI (Figure 3) showed L4 vertebral body abnormalities consisting of low Tl and high T2 signal as well as post-contrast enhancement that extended into the epidural and paravertebral spaces. Further workup included blood cultures and CT-guided needle biopsy of the L4 vertebral body (Figure 4). The blood and biopsy cultures both grew methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Treatment was initiated with IV vancomycin. At that time, lumbar spine plain radiography (Figure 5) showed narrowing of the L4-L5 disk space.

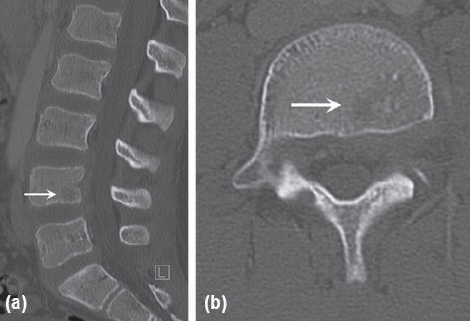

Figure 2.

Lumbar spine CT for patient one. (a) Sagittal and (b) axial views showing a rounded lucent area in the posterior-inferior portion of the L4 vertebral body.

Figure 3.

MRI performed six days after initial presentation. (a) Sagittal Tl-weighted MRI showing low signal intensity of the entire 14 vertebral body. (b) Sagittal T2-weighted image showing a small hyperintense lesion in 14 vertebral body. (c) Sagittal Tl-weighted post-gadolinium image with fat suppression showing 14 vertebral body enhancement. (d) Axial T1-weighted post-gadolinium image showing epidural (black arrow) and paravertebral (white arrow) enhancement

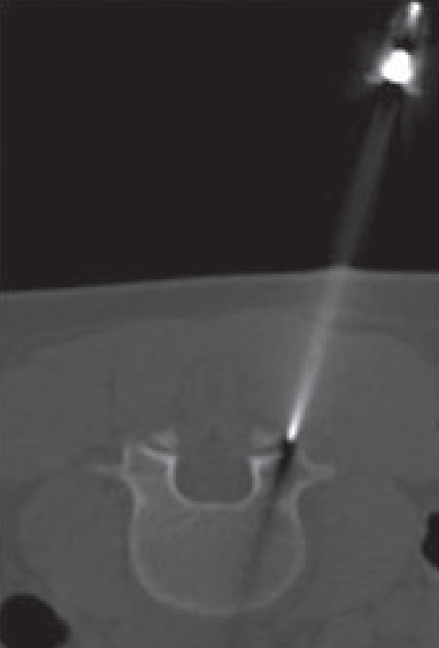

Figure 4.

CT-guided needle biopsy of L4 vertebral body

Figure 5.

Lateral lumbar radiograph nine days after initial presentation showing L4-L5 disk space is narrowing.

The patient was discharged but readmitted one week later for worsening back and leg pain. Lumbar spine plain radiography at that time continued to show L4-L5 disk-space narrowing (Figure 6). An MRI of the lumbar spine was repeated and showed progression of the L4 osteomyelitis to include the L5 vertebral body and the L4-L5 intervertebral disc (Figure 7). An epidural abscess was also present The infectious disease consultation team discontinued the IV vancomycin and started a continuous IV infusion of nafcillin along with oral rifampin. Antibiotic treatment was continued uneventfully for a total of six weeks and the patient was symptom free at three-month follow-up.

Figure 6.

Lateral lumbar radiograph 19 days after initial presentation showing L4-L5 disk height loss (arrow) and endplate blurring (curved arrows).

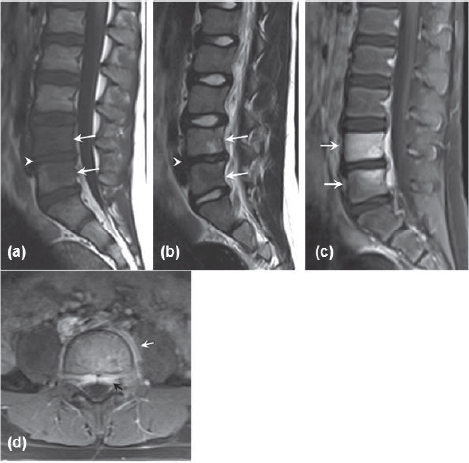

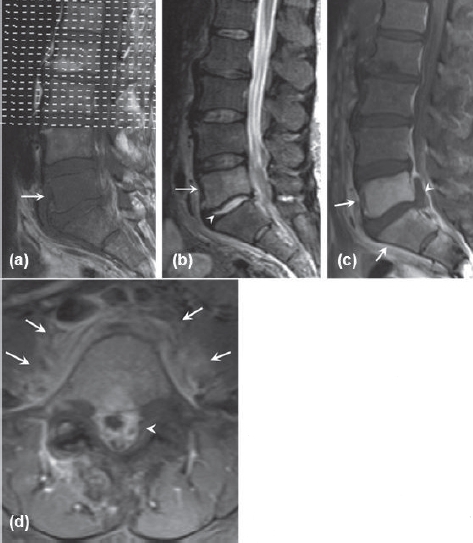

Figure 7.

MRI of the lumbar spine performed 17 days after initial presentation. (a) Sagittal T1-weighted image showing hypointense lesions in L4 and L5 vertebral bodies (arrows) and disk height loss (arrowhead). (b) Sagittal T2-weighted image showing hyperintense lesion in L4 vertebral body and hypointense lesion in L5 vertebral body (arrows). There is loss of signal intensity in L4-L5 disk (arrowhead). (c) Sagittal T1-weighted post-gadolinium image with fat suppression showing L4 and L5 vertebral body enhancement. (d) Axial Tl-weighted post-gadolinium image showing epidural (black arrow) and paravertebral (white arrow) enhancement.

Case 2

A 52-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and melanoma presented to her local hospital with three weeks of intermittent back and leg pain with episodes of lower extremity weakness. Prior treatment included NSAIDs and muscle relaxants, but both had been unsuccessful at alleviating her pain. At presentation, she also had cellulitis of the left elbow but no history of fevers or chills. Initial lab work was significant for a white blood cell count of 25.3 × 103/uL (normal: 3.7-10.5 × 103/uL), ESR of 81 mm/hr (normal: 0-15 mm/hr), and CRP of 30 mg/dL(normal: <0.5 mg/dL). The initial lumbar spine MRI (Figures 8a and 8b) showed low T1 and high T2 signal in the L5 vertebral body and high T2 signal in the L5-S1 disk. This MRI study was performed without intravenous gadolinium. The follow-up examination two days later was performed with gadolinium and it highlighted an epidural abscess, paravertebral inflammation, and S1 vertebral body enhancement (Figures 8c and 8d). Plain radiography of the lumbar spine showed normal alignment and no bony changes (Figure 9). The MRI findings were initially concerning for infectious spondylodiscitis versus metastatic melanoma because of the patient’s previous history of melanoma.

Figure 8.

Initial MRI for patient two. (a) Sagittal T1-weighted image showing hypointense lesion in the L5 vertebral body. (b) Sagittal T2-weighted image with hyperintense lesion in the L5 vertebral body and hyperin-tense L5-S1 disk. (c) Sagittal Tl-weighted post-gadolinium image with fat suppression showing L5 and S1 vertebral body enhancement (arrows) and epidural abscess (arrowhead). (d) Axial T1weighted post-gadolinium image showing epidural (arrowhead) and paravertebral (arrow) enhancement

Figure 9.

Lumbar plain radiograph. Changes of spondy-lodiscitis are not yet evident

The patient underwent CT-guided needle biopsy of her L5-S1 intervertebral disc (Figure 10). The biopsy specimen and one of her blood cultures were positive for MSSA Vancomycin was initiated to treat the MSSA until sensitivity studies returned, at which point treatment was shifted to nafcillin. On follow-up at one month she continued to have back and leg pain. Conventional radiography of the lumbar spine showed progressive loss of L5-S1 disk space height and blurring of the inferior endplate of L5 and the superior endplate of S1 (Figure 11). An MRI of the lumbar spine showed progression of spondylodiscitis to include the vertebral bodies of L5 and S1 as well as the L5-S1 disk (Figure 12). Upon completion of eight weeks of nafcillin therapy, her back and leg pain had improved but had not completely resolved.

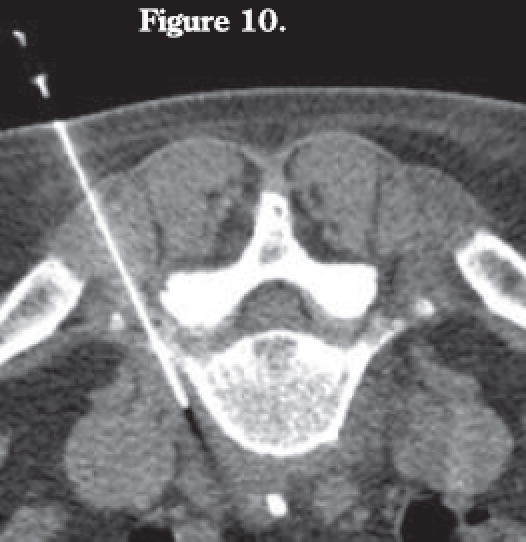

Figure 10.

CT-guided needle biopsy of L5 paravertebral fluid collection.

Figure 11.

Lateral lumbar radiograph one month after initial presentation showing L5-S1 disk height loss (arrow) and endplate blurring at L5-S1 interface (curved arrows).

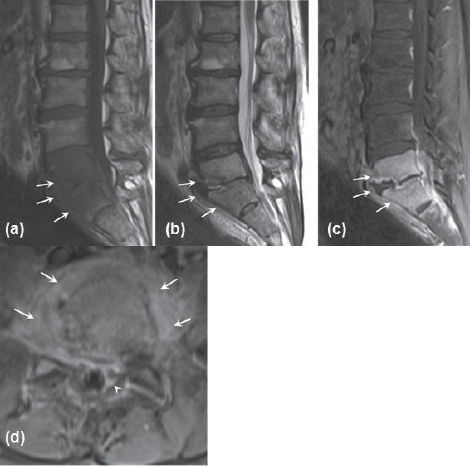

Figure 12.

MRI of me lumbar spine performed one month after initial presentation. (a) Sagittal Tl-weighted image showing hypoin-tense lesions in the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies with loss of disk space. (b) Sagittal T2-weighted image showing hyperintense lesions in the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies. (c) Sagittal T1-weighted post-gadolinium image with fat suppression showing L5 and S1 vertebral body enhancement and prominent endplate irregularity. (d) Axial T1-weighted post-gadolinium image showing epidural (arrowhead) and paravertebral (arrows) enhancement.

DISCUSSION

Our cases are unique in that both patients presented with MRI findings different from those typically reported in the literature. Most studies on spondylodiscitis report the classic finding of involvement of two adjacent vertebrae in the majority of cases. The fact that only a single vertebral body showed abnormalities on MRI led to diagnostic confusion. In addition, patient one also presented with hypointense T2 signal in the single affected vertebral body.

Although most studies in the literature do not focus on cases like ours, several studies have noted the small prevalence of cases with single vertebral body involve-ment Shih, et al.8 focused specifically on this topic and found nine cases of single-segment vertebral osteomyelitis out of a series of 107 patients (8.4%). Three of these cases were due to tuberculosis and the other six were pyogenic in nature. Their study found that the presence of anterior cortical disruption of the vertebra and upward subligamentous spread of the infection are the two most prevalent features that can aid in earlier diagnosis of single-segment spondylodiscitis. In another study10 with 44 patients having disk infection where tuberculous and postoperative infections were excluded, only three of these patients showed signs of involvement of a single vertebral level for an incidence of 6.8%. In all three patients with single segment spondylodiscitis, only the superior vertebra was affected. This is the same pattern we observed in our two cases.

Other investigators have studied the MR characteristics of spondylodiscitis and noted some atypical appearances. Gillams, et al.11 reported on a series of 25 patients and found that early imaging tended to show atypical MR presentations. One patient presented with single vertebral body involvement that later evolved to include the disk and adjacent vertebral body. Two other patients in this study had single vertebral body and disk involvement initially which later progressed to include the adjacent vertebral body as well. The incidence of single vertebral body involvement with or without disk involvement in this study was three out of 25 (12%). Another series5 with 27 patients reported that four of them (15%) had single vertebral body involvement with or without disk involvement initially, which also later progressed to include the adjacent vertebra. Thrush, et al.12 reported one case out of 14 patients with a similar presentation. Other atypical appearances of spondylodiscitis reported in the literature include a single vertebral compression fracture with a normal disk,13 and initial presentation in an 81-year-old woman with only disk involvement and no vertebral body findings9.

Similar to our case one is the atypical finding of hypointense T2 signal in the involved vertebral body also observed in 17 of 39 cases (44%) documented by Dagirmanjian, et al.14 Sclerosis of the bony trabeculae was postulated as an explanation. They did not, however, find a statistically significant correlation between sclerosis on the plain radiographs and the hypointense foci on T2 weighted images.

While plain radiography is often used as an initial imaging modality for patients with back pain, MRI is considered the most sensitive and specific imaging study for early spondylodiscitis.15 The typical MRI characteristics of spondylodiscitis are low T1 and high T2 signal intensity in the vertebral bodies and the intervertebral disk between them.14-16 Avid gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted imaging in the affected tissues is also characteristic. One study10 looked at 46 patients with culture-positive pyogenic spondylodiscitis and found that certain imaging parameters had very good sensitivity for diagnosing spinal infection (paraspinal or epidural enhancement—98% sensitivity, disk enhancement—95% sensitivity, hyperintense T2 disk signal—93% sensitivity, and erosion of at least one vertebral end plate—84% sensitivity) while other parameters were less sensitive (decreased intervertebral disk height—52% sensitivity, and hypointense Tl disk signal—30% sensitivity).

The general consensus from the literature5,8,10-12 is that spondylodiscitis with single vertebral body involvement reflects early presentation of the disease. This assertion is supported by the cases presented here as they both progressed to include the adjacent vertebral body. Many of the cases reported in the literature have shown a similar progression.

In summary, infectious spondylodiscitis is a disease that affects both adults and children and is becoming more prevalent. Early presentation of this disease may have an atypical appearance such as involvement of a single vertebra on MRI. As disease incidence increases and more patients are scanned earlier in the disease process, atypical presentations such as these may become more common. To avoid delays in diagnosis, spondylodiscitis should be included in the differential diagnosis when imaging studies reveal atypical findings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Infect. 2008;56:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimmerli W. Clinical Practice. Vertebral Osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1022–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0910753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaramillo-de La Torre J, Bohinski R, Kuntz C., 4th Vertebral osteomyelitis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2006;17:339–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyers S, Wiener S. Diagnosis of hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis by magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:683–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cahill D, Love L, Rechtine G. Pyogenic osteomyelitis of the spine in the elderly. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:878–86. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.6.0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stabler A, Reiser M. Imaging of spinal infection. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39:115–35. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin T, Huang K, Hou S. Early diagnosis of single segment vertebral osteomyelitis-MR pattern and its characteristics. Clin Imaging. 1999;23:159–67. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(99)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millot F, Bonnaire B, Clavel G, Deramond H, Fardellone P, Grados F. Hematogenous Staphylococcus aureus discitis in adults can start outside the vertebral body. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:76–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledermann H, Schweitzer M, Morrison W, Car-rino J. MR imaging findings in spinal infection: rules or myths? Radiology. 2003;228:506–14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2282020752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillams A, Chaddha B, Carter A. MR appearances of the temporal evolution and resolution of infectious spondhylitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:903–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thrush A, Enzmann D. MR imaging of infectious spondylitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:1171–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abe E, Yan K, Okada K. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis presentating as single spinal compression fracture: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:639–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dagirmanjian A, Schils J, McHenry M, Modic M. MR imaging of vertebral osteomyelitis revisited. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1539–43. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.6.8956593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varma R, Lander P, Assaf A. Imaging of pyogenic infectious spondylodiskitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39:203–13. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modic M, Feiglin D, Piraino D, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MR. Radiology. 1985;157:157–66. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.1.3875878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]