Abstract

Resistance to the beta-lactam class of antibiotics in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is mediated by PBP 2a, a synthetic bacterial cell wall penicillin-binding protein with a low affinity of binding to beta-lactams that is encoded by mecA. Beta-lactams that bind to PBP 2a with a high affinity and that are highly active against MRSA are under development. The potential for the emergence of resistance to such compounds was investigated by passage of homogeneous MRSA strain COL in L-695,256, an investigational carbapenem. A highly resistant mutant, COL52, expressed PBP 2a in which a two-amino-acid deletion mutation and three single-amino-acid substitution mutations were present. To examine the effects of these mutations on the resistance phenotype and PBP 2a production, plasmids carrying (i) PBP 2a with two or three of the four mutations, (ii) wild-type PBP 2a, or (iii) COL52 PBP 2a were introduced into methicillin-susceptible COL variants COLnex and COL52ex, from which the staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) has been excised, as indicated by the “ex” suffix. Two amino acids substitutions, E→K237 within the non-penicillin-binding domain and V→E470 near the SDN464 conserved penicillin-binding motif in the penicillin-binding domain in COL52, were important for high-level resistance. The highest level of resistance was observed when all four mutations were present. The emergence of PBP 2a-mediated resistance to beta-lactams that bind to PBP 2a with a high affinity is likely to require multiple mutations in mecA; chromosomal mutations appear to have a minor role.

Staphylococcal resistance to the beta-lactam class of antibiotics, termed methicillin resistance, is mediated by PBP 2a, a low-affinity penicillin-binding protein (PBP). The beta-lactam antibiotics that are used clinically do not bind to PBP 2a at therapeutic concentrations and therefore lack efficacy against infections caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococci. With the solution of the crystal structure of a soluble derivative of PBP 2a, low-affinity binding can be attributed at least in part to an energetically unfavorable acylation reaction of the active site serine due to the slippage of the beta-lactam molecule within a long groove that serves as the initial, reversible binding site in the formation of the Michaelis-Menten complex (16).

Several cephalosporin and carbapenem derivatives that bind to PBP 2a with 100-fold or higher affinities than those of other beta-lactams and which are active in vitro and in vivo against methicillin-resistant staphylococci have been synthesized (2, 6, 7, 13, 20). These compounds have in common a relatively extended side chain attached to the α ring of the beta-lactam compound core (3, 16). This structural feature permits the molecule to be positioned within the groove in such a way that the acylation reaction proceeds at a rate more rapid than that in its lower-affinity relatives. Two of these compounds, BAL 9141 and RWJ 54428, have been tested in phase I trials with humans (7, 17). It is quite likely that within the next few years a PBP 2a-binding beta-lactam will become available for clinical use. Given the proficiency demonstrated by methicillin-resistant strains of staphylococci in acquiring resistance to literally any and every antimicrobial and because of cross-resistance among beta-lactam antibiotics in particular, there is concern that resistance will rapidly develop once these investigational agents become available. A famous property of methicillin-resistant staphylococci is their ability to develop high-level resistance upon exposure to beta-lactams to which they are apparently susceptible in vitro (4). Ryffel et al. (18) have reported that the high-level resistance expressed by the minority population of methicillin-resistant staphylococci was due to a chromosomal mutation(s) (chr*) located outside of mecA, the gene encoding PBP 2a. To assess this potential for the emergence of resistance, experiments were conducted to investigate the mechanism of resistance in COL52, a mutant of homogeneous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain COL obtained by repeated passage in the presence of L-695,256, an investigational carbapenem with a high affinity of binding to PBP 2a (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth condition.

The strains used in the study are listed in Table 1. The five mecA-encoding strains were strain COLn (nafcillin MIC = 400 μg/ml); strain COL52 (nafcillin MIC = 3,200 μg/ml); strain BB270 (nafcillin MIC = 400 μg/ml); strain COL8a, a spontaneous methicillin-susceptible variant of COLn due to the presence of a point mutation introducing a stop codon at amino acid residue 115; and strain N315 (nafcillin MIC = 50 μg/ml). All MRSA strains except strain N315 were tetracycline susceptible and β-lactamase negative. Strain COL52 was obtained by serial passage of COL for 1 month in broth containing L-695,256, an investigational carbapenem with a high affinity of binding to PBP 2a (2). The L-695,256 MIC for COL52 is 48 μg/ml (whereas for COL it is ≤1.0 μg/ml), and in agar plating assays COL52 grows in the presence of L-695,256 at concentrations up to 40 μg/ml. COL52 PBP 2a is not detectable by fluorography with [3H]penicillin at concentrations up to 50 μg/ml (concentrations of 10 to 15 μg/ml can be used to label PBP 2a in COL) (5).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmid vectorsa

| Strain | Description | Relevant phenotype or genotype | Beta-lactamase plasmid | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA strains | ||||

| COL | Homogeneous methicillin-resistant strain | Mcr, Tcr | 21 | |

| COLn | Tcs strain from COL | Mcr | This study | |

| COL52 | An antibiotic-selected mutant of COLn expressing a higher level of resistance | Mcr | 2 | |

| COL8a | Methicillin-susceptible spontaneous mutant of COLn due to the presence of a premature stop codon at amino acid residue 115 in PBP 2a | Mcs | 2 | |

| BB270 | Homogeneous methicillin-resistant strain, a SCCmec-positive transductant of NCTC8325 | Mcr | 1 | |

| N315 | Heterogeneous methicillin-resistant strain carrying functional mecI-mecR1 regulatory genes of mecA | Mcr | Beta-lactamase positive | 11 |

| mecA-negative experienced hosts | ||||

| COLnex | COLn from which SCCmec was excised | Mcs | This study | |

| COL52ex | COL52 from which SCCmec was excised | Mcs | This study | |

| COL8aex | COL8a from which SCCmec was excised | Mcs | This study | |

| BB270ex | BB270 from which SCCmec was excised | Mcs | This study | |

| N315ex | N315 from which SCCmec was excised | Mcs | Beta-lactamase positive | 14 |

| mecA-negative naïve host RN4220 | Restriction-deficient derivative of NCTC8325-4 | Mcs | 15, 17 |

Abbreviations: Mcs, methicillin susceptible; Mcr, methicillin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant; Tcs, tetracycline susceptible; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant.

Strain BB270 is a staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec)-positive methicillin resistance transductant of S. aureus strain NCTC8325, which has high-level resistance (nafcillin MIC = 400 μg/ml) (1). Strain N315 is a heterogeneous MRSA strain which contains SCCmec carrying the functional mecI-mecRI regulatory genes of mecA (11).

mecA-negative S. aureus variants were constructed from mecA-encoding strains by introducing temperature-sensitive plasmid pSR2 into them. pSR2 contains ccrA and ccrB genes encoding recombinases that precisely excise SCCmec from the chromosome (14). The “ex” suffix designates an S. aureus variant from which mecA has been excised (e.g., COLnex is the mutant of COLn from which SCCmec has been excised). RN4220 is a naturally mecA-negative methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) strain that is a restriction-deficient derivative of NCTC8325-4 (15, 17).

All S. aureus strains and transformants were cultivated in Trypticase soy broth or Trypticase soy agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with aeration, unless indicated otherwise. Tetracycline (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. Nafcillin (Sigma) was used for population analysis.

Plasmids and DNA manipulations.

For the transformation experiments, mecA of strain COLn or COL52 was cloned into the BamHI site of S. aureus plasmid pAW8 or pAW10; pAW8 and pAW10 are Enterococcus faecalis-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors with selectable markers for tetracycline resistance (23). The primers used in this study are shown in Table 2, and the locations of the sequences of the six primers used for plasmid constructions are indicated in Fig. 1. The mecA product, including its promoter and the first 223 nucleotides of mecR1 on pYK20COLn or pYK21COL52, was obtained by PCR amplification of COLn or COL52 mecA with primers K34 and K38 and 1 U of Clontaq polymerase (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Plasmids pYK26, pYK27, pYK28, and pYK29 were constructed by establishment of site-directed point mutations by PCR (24). For the first round of PCR, we amplified two PCR fragments with two sets of primers for each plasmid: primers K34 and K237rc for COL52 DNA, primers K237 and K38 for COLn(pYK26) DNA, primers K34 and E470rc for COL52 DNA, primers E470 and K38 for COLn(pYK27) DNA, primers K34 and E470rc for COLn DNA, primers E470 and K38 for COL52(pYK28) DNA, primers K34 and K237rc for COLn DNA, and primers K237 and K38 for COL52(pYK29) DNA. A second round of PCR was performed with primers K34 and K38 and by use of the two fragments amplified from each plasmid as templates. Each amplified fragment was digested with the BamHI restriction enzyme and then cloned into pAW10. All plasmids were isolated from E. coli DH5α by standard procedures, and the amplified DNA was sequenced (sequencing was performed by the University of California, San Francisco, Biomolecular Resources Center DNA sequencing facility) to confirm the absence of any unwanted mutations. The strains were transformed with plasmids by electroporation (14). After a 48-h incubation the transformants were tested for mecA by PCR amplification with the K34-K38 primer pair.

TABLE 2.

Synthetic oligonucleotides primers in mecA genea

| Primer purpose and designation | Sequenceb | Nucleotide positions |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | ||

| K10 | 5′-AGTAGCTCAACGAGCTGAAAAT-3′ | 29943-29964 |

| K19 | 5′-ATACGGAGAAGAAGTTGTAGCA-3′ | 33658-33637 |

| K15 | 5′-AGCACACCTTCATATGACGTCT-3′ | 32473-32494 |

| K16 | 5′-TGGATCAAAATTGGGTACAAGA-3′ | 31991-32012 |

| K17 | 5′-AGTTGTAGTTGTCGGGTTTGGT-3′ | 31425-31446 |

| K18 | 5′-TGGCAATATTAACGCACCTCACT-3′ | 33012-33034 |

| Plasmid construction | ||

| K34 | 5′-TATGCGGATCCTCGTGTCAGATACATTTCGATTCA-3′ | 31068-31091 |

| K38 | 5′-ATTTCGGATCCGTTGTAGCAGGAACACAAATGAATAAC-3′ | 33645-33619 |

| K237 | 5′-CATCTTACAACTAATGAAACAAAAAGTCGTAACTATCCTC-3′ | 32083-32122 |

| K237rc | 5′-GAGGATAGTTACGACTTTTTGTTTCATTAGTTGTAAGATG-3′ | 32122-32083 |

| E470 | 5′-CAAGATAAAGGAATGGCTAACTACAATGCCAAAATCTCAG-3′ | 33298-33337 |

| E470rc | 5′-CTGAGATTTTGGCATTGTAGTTAGCCATTCCTTTATCTT-3′ | 33337-33297 |

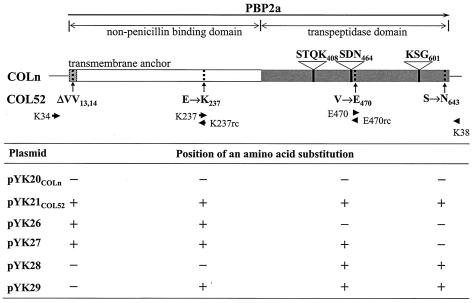

FIG. 1.

Structural map of PBP 2a in strains COLn and COL52 and positions of the substituted amino acid sequences on the six plasmids. The arrows in the map of PBP 2a indicate the direction of mecA transcription. The striped, white, and gray regions indicate the transmembrane anchor, the nPBD, and the transpeptidase domain, respectively. The locations of three penicillin-binding motifs in the penicillin-binding (transpeptidase) domain are indicated by black lines. The amino acid mutations in PBP 2a of strain COL52 are indicated by dotted lines. The positions of the primers for PCR amplification are indicated by arrowheads. The table at the bottom shows the mutations, indicated by a plus sign, present in the plasmid constructs used to express wild-type or mutant PBP 2a.

Population analysis.

Population analysis was done by the agar plate method, in which approximately 108 CFU was quantitatively inoculated onto a series of agar plates containing increasing concentrations of nafcillin (Sigma) (22).

Detection of PBP 2a.

The strains were assayed for PBP 2a production by Western blotting. S. aureus membrane proteins were prepared from late-exponential-stage cultures. An overnight culture (100 μl each) was inoculated into 50 ml of fresh Trypticase soy broth and allowed to grow to an optical density at 578 nm of 1.0. The cells were harvested and washed with buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.5]) and then resuspended in the same buffer. Lysostaphin, DNase, and RNase were added to final concentrations of 100, 20, and 10 μg/ml, respectively; and then the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 4,400 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 110,000 × g for 40 min. The resultant pellet was washed twice and resuspended in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Membrane proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred as described previously (24). PBP 2a was detected with a mouse anti-PBP 2a monoclonal antibody (a gift of Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan) as the primary antibody (diluted 1:100,000) and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Promega, Madison, Wis.). We detected bound antibodies by color development, as directed by the manufacturer.

RESULTS

Determination of the PBP 2a sequence in strain COL52.

The sequences of chromosomal mecA, its promoter, and a part of mecR1 deleted from strains COLn and COL52 were determined from the DNA obtained by PCR with primers K10 and K19 (Table 2). The mecA nucleotide sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence of COLn were identical to the sequences of the mecA regions in NCTC10442 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB033763) (12) and PBP 2a (GenBank accession no. CAA68684) (19) reported previously. The deduced amino acid sequence of PBP 2a in COL52 was identical to that in COLn except for five amino acid changes: deletion of two contiguous valine residues at residues 13 and 14 at the N terminus within the membrane anchor of the non-penicillin-binding domain (nPBD) (9, 10) and three amino acid substitution mutations, E→K at residue 237 within the nPBD, V→E at residue 470 near the SDN464 conserved penicillin-binding motif in the penicillin-binding domain (PBD), and S→N at residue 643 in the PBD near the carboxy terminus (Fig. 1).

Phenotypic expression of COL52 mecA on the plasmid in MRSAex or MSSA transformants.

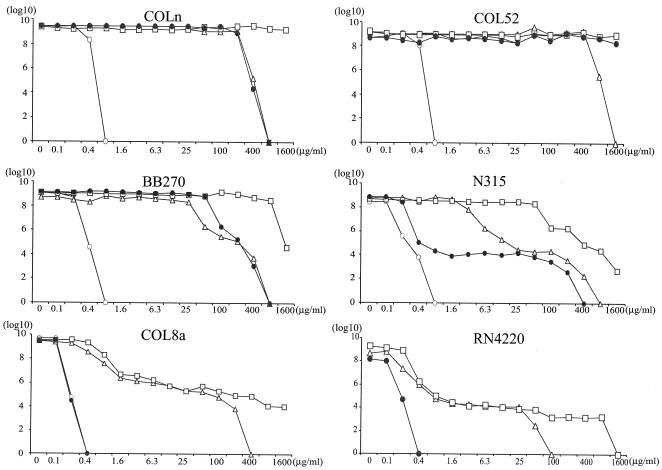

Three plasmids, pYK20COLn(carrying wild-type mecA), pYK21COL52 (carrying COL52 mecA), and pAW8 (vector), were separately introduced into several MRSAex strains (i.e., methicillin-susceptible variants of methicillin-resistant strains from which SCCmec was excised) or MSSA strain RN4220. The selective pressure of beta-lactam antibiotics that might influence the phenotype was avoided by selecting for the plasmid, but not mecA, with tetracycline only. The effect of the host chromosome on the methicillin resistance phenotype was assessed by population analysis (Fig. 2). All MRSAex(pAW8) and RN4220(pAW8) transformants were susceptible to nafcillin at concentrations ≤0.8 μg/ml. COLn(pAW8) and COL52(pAW8) transformants showed homogeneous resistance, with the numbers of CFU of the former strain increasing up to a nafcillin concentration of 800 μg/ml and the numbers of CFU of the latter strain increasing up to a nafcillin concentration of >1,600 μg/ml. The BB270(pAW8) and N315(pAW8) transformants expressed class 3 heterogeneous resistance (i.e., 1 CFU in 102 to 104 with 100 μg of nafcillin per ml) and class 2 heterogeneous resistance (1 CFU in 105 to 106 with 100 μg of nafcillin per ml), respectively (22). The COL8a(pAW8) transformants were fully susceptible, consistent with the point mutation present in chromosomal mecA. When the MRSAex, COLnex, COL52ex, and BB270ex transformants were transformed with wild-type mecA on plasmid pYK20COLn, each expressed resistance in a pattern that was identical to that of each parent MRSA(pAW8) transformant. N315ex(pYK20COLn) transformants were slightly less heterogeneous than the parent, as evidenced by a shift to the right in the population analysis curve, probably due to the strong mecI repressor activity in N315(pAW8), which is absent from the unregulated mecA of pYK20COLn. COL8aex(pYK20COLn) transformants expressed heterogeneous resistance, indicating that, in addition to the point mutation within mecA, an additional mutation or mutations altering the normally homogeneous phenotype were also present in COL8a. Introduction of pYK21COL52 into the genetic backgrounds of strains COLnex, COL52ex, and BB270ex, all of which express a relatively high level of resistance when wild-type mecA is present, exhibited an even higher level of resistance, which was homogeneous, with virtually 100% of the CFU able to grow in the presence of nafcillin at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. The numbers of CFU increased in the presence of 1,600 μg of nafcillin per ml, the highest concentration tested. The strains with the RN4220, COL8aex, and N315ex backgrounds, which express heterogeneous resistance with wild-type mecA, retained their heterogeneous resistance patterns when they were transformed with pYK21COL52, although each had a resistant subpopulation that grew in the presence of up to 800 to 1,600 μg of nafcillin per ml.

FIG. 2.

Population analysis showing heterogeneous or homogeneous resistance phenotypes for five MRSA strains and one MSSA strain, RN4220, transformed with pYK20COLn (open triangles) expressing wild-type PBP 2a or with pYK21COL52 (open squares) expressing mutant PBP 2a. COLn and COL52 naturally express homogeneous methicillin resistance; BB270 and N315 express heterogeneous resistance; COL8a, a spontaneous mutant of COL that does not express PBP 2a, and RN4220 are methicillin susceptible. The phenotypes of the recipient parent and the mutant of the parent from which mecA was excised and that was transformed with plasmid vector pAW8 are indicated by solid and open circles, respectively. The y axis indicates the number of cells (in log10 CFU per milliliter) growing on nafcillin-containing agar; the concentration of nafcillin is shown on the x axis.

Effects of amino acid substitutions in COL52 PBP 2a on phenotype and expression.

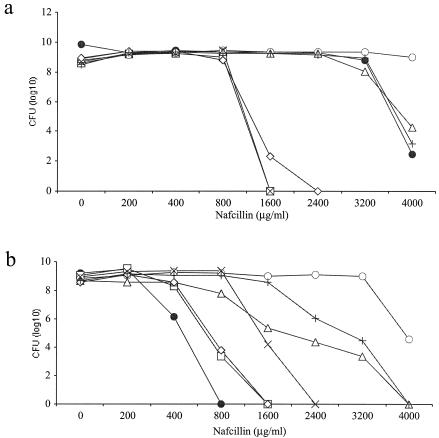

To investigate which amino acid substitutions in mutant COL52 PBP 2a contributed to the highly resistant phenotype, four plasmids, pYK26, pYK27, pYK28, and pYK29, carrying sequences with two or three of the four amino acid substitutions of COL52 PBP 2a were constructed (Fig. 1). Attempts were made to construct a sequence with a single mecA mutation, but multiple attempts to obtain DH5α transformants with a single mutation were unsuccessful for reasons that are unclear, limiting the experiments to examination of these four constructs. Each plasmid was introduced into strain COLnex or COL52ex, and the phenotype was assayed by population analysis with nafcillin (Fig. 3). COL52ex transformants (Fig. 3a) with either plasmid pYK26 or plasmid pYK28, each of which encoded two mutations, both of which were located in either the nPBD or the PBD of the molecule, respectively, showed a homogeneous pattern of resistance similar to that of strain COL52ex transformed with wild-type mecA on pYK20COLn. When pYK28, which encodes both mutations in the PBD, was introduced into COLnex, it had the same effect on the phenotype as wild-type mecA (Fig. 3b). The slightly different phenotypes of nafcillin resistance between the COLnex and COL52ex transformants can be attributed to the differences in the genetic backgrounds of the chromosomes between strains COLn and COL52 with pYK26, which encodes the two mutations in the nPBD, resulted in a fourfold increase in the nafcillin concentration in which the COLnex recipient could grow.

FIG. 3.

Population analysis of COL52 and COL52ex transformants (a) or COLn and COLnex transformants (b), as follows: parent recipient containing pAW8 (closed circles), recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK20COLn (open squares), recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK21COL52 (open circles), recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK26 (multiplication signs), recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK27 (open triangles), recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK28 (open diamonds), and recipient from which mecA was excised containing pYK29 (plus signs).

COL52ex transformants with pYK27 or pYK29, each of which contained three of the four mutations of COL52 mecA involving both the nPBD and the PBD, exhibited the same high level of resistance as the COL52(pAW8) parent strain, all of which were slightly less resistant than the COL52ex transformant complemented with plasmid-encoded COL52 mecA. COLnex transformants with pYK27 or pYK29 also exhibited high-level resistance that exceeded that achieved with wild-type mecA by about eightfold. The levels of resistance of COLnex transformants were comparable to those of COL52; however, the highest level of resistance required the presence of all four mutations.

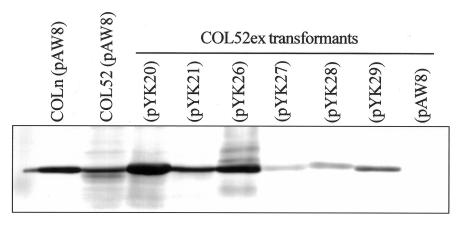

The amounts of PBP 2a detectable on immunoblots varied considerably among the transformants and bore no relationship to the resistance phenotype. COL52ex transformed with pYK20COLn, which encodes wild-type mecA, or pYK26, in which both mutations were located in the nPDB, produced amounts of PBP 2a that were similar to the amount produced by the COLn(pAW8) control strain (Fig. 4). Compared to COLn(pAW8), slightly less PBP 2a was detectable in both the COL52(pAW8) and the COL52ex(pYK21COL52) transformants. The amounts of PBP 2a in the COL52ex(pYK27), COL52ex(pYK28), and COL52ex(pYK29) transformants were significantly reduced relative to those in all other transformants.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis for expression of mecA in transformants with plasmid vector pAW8 or a plasmid encoding wild-type mecA (pYK20COLn) or mutant mecA (pYK21COL52, pYK26, pYK27, pYK28, pYK29).

DISCUSSION

The methicillin resistance phenotype is determined both by mecA expression and by the chromosomal elements constituting the genetic background within which mecA resides. The potential contribution of each to the development of resistance to beta-lactams, which exhibit a high affinity of binding to PBP 2a, was assessed by passage of strain COL with a homogeneous pattern of resistance in L-695,256, an investigational carbapenem that is active against MRSA in vitro and in vivo (2). The strain obtained after passage, highly beta-lactam-resistant mutant strain COL52, produced a mutant PBP 2a resulting from four mutations within mecA, two of which were located in the nPBD and two of which were located in the PBD. The contribution of the genetic background to the phenotype was determined by introducing this mutant PBP 2a into six recipient strains that differed in the heterogeneities of their resistance patterns. For each of the recipient strains tested, the presence of mutant COL52 PBP 2a resulted in an increase in the concentration of nafcillin in the presence of which the highly resistant subpopulation could grow. However, the overall phenotypic pattern of resistance, heterogeneous or homogeneous, tended to be the same as that observed with wild-type PBP 2a.

The contribution of background chromosomal mutations in COL (vis-à-vis those located within mecA) as a consequence of antibiotic passage to the overall level of resistance was minimal. Wild-type mecA in COLn, whether present as a single chromosomal copy or encoded on a low-copy-number plasmid vector, yielded identical population analysis curves with a steep falloff of growth over the narrow concentration range of 400 to 800 μg of nafcillin per ml. Wild-type mecA introduced into the COL52 mutant shifted the curve to twofold-higher concentrations. On the other hand, introduction of mutant mecA obtained from COL52 into either the COL or the COL52 background shifted the growth curve to 5- to 10-fold-higher concentrations in both. These data indicate that mutations in mecA, rather than chromosomal mutations at other loci, mediate the very high levels of resistance that were observed. This result is entirely consistent with PBP2a being the primary target determining susceptibility and resistance to beta-lactams in MRSA strains.

Mutations associated with this high level of resistance were investigated by constructing mecA genes in which mutations were present in either the PBD or the nPBD, or both. Unfortunately, the failure to construct mutants with single mutations limited the experiments to these constructs, but the results were informative. Although the PBD is directly involved in drug binding, surprisingly, the two mutations within it had virtually no effect on the resistance phenotype in either the COLn or COL52 background compared to that in wild-type PBP 2a background. The two mutations in the nPBD (one of which was located in the dispensable membrane anchor and which is unlikely to play much of a role in determining binding [16]) had no effect on the phenotype of the COL52 recipient compared to that of the strain with wild-type PBP 2a but resulted in a doubling of the nafcillin concentration in the presence of which COLn could grow. In the presence of three or four mutations within both the PBD and the nPBD, the very high levels of resistance that were observed with the COL52 mutant were reproduced. These results suggest that two amino acids substitutions, E→K237 and V→E470, in COL52 are principally important for the high level of resistance, as both of these substitutions were present in the transformants with pYK27 and pYK29, which expressed high-level resistance. When the mutations were not present together (as in pYK26 and pYK28), the transformants were less resistant. Interestingly, the nPBD contributed to the phenotype, although this region of the molecule is structurally distinct from that which is thought to physically interact with beta-lactams.

The reason for the differences in the amounts of immunoreactive PBP 2a for the various plasmid transformants is not clear. The amounts of membrane protein loaded for each preparation were similar. When we analyzed membrane proteins by Coomassie blue staining, the PBP 2a proteins of COLn, COL52ex(pYK20COLn), and COL52ex (pYK26) could be visualized; but those of the COL52, COL52ex(pYK27), COL52ex(pYK28), and COL52ex(pYK29) transformants couldnot (data not shown). Possible explanations for this are transcriptional or translational down-regulation, loss of protein from the membrane because of structural instability or turnover, or differences in immunoreactivity with the anti-PBP 2a monoclonal antibody. Differences in immunoreactivity seem unlikely, because similar results were obtained with polyclonal anti-PBP 2a antiserum (data not shown) (8) and the amount of PBP 2a detectable in the transformant with pYK29 was less than that detectable in the transformant with pYK21COL52, which differed only by a mutation in the transmembrane anchor region, which is not the epitope recognized by the monoclonal antibody. Unless there is some feedback loop involving the PBP 2a product, transcriptional down-regulation seems unlikely because the same promoter is present in all constructs. Translational and posttranslational events are possibilities. Interestingly, all four transformants with the least amount of detectable PBP 2a had one or two mutations in the PBD (in Fig. 4, compare pYK26 with mutations only in the nPBD to pYK21COL52, pY27, pYK28, and pYK29, all of which had mutations in the PBD), and these may contribute, for example, to instability of the molecule or increased protease susceptibility.

In summary, the results of the passage experiments described here indicate that multiple mutations both in mecA and at other chromosomal loci contribute to the emergence of very-high-level resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in MRSA. This level of resistance is probably enough to confer cross-resistance even to beta-lactam antibiotics which bind to PBP 2a with a relatively high affinity, based on the increases in the MICs of penicillin and L-695,256 that were observed. The contribution of chromosomal loci appears to be relatively minor because very-high-level resistance was produced in strains with a variety of genetic backgrounds. Because the experimental approach did not use a serial analysis of stepwise mutants but used an after-the-fact reconstruction of a mutant with high-level resistance, the data cannot exclude the possibility that chromosomal loci do play roles at intermediate steps. The results are somewhat comforting in terms of the development of resistance, in that repeated serial passages were required to produce a highly resistant mutant and three to four PBP 2a mutations were needed to reproduce high-level resistance in transformants, suggesting that resistance is unlikely to emerge in a single step. On the other hand, these experiments in no way exclude the possibility of the emergence of a completely novel resistance mechanism (for example, the presence of a beta-lactamase capable of inactivating compounds stable in the presence of penicillinases) or the acquisition of a novel target able to circumvent beta-lactam inactivation, as was the case with the ancestral methicillin-resistant strain and its acquisition of mecA. Given the facility with which staphylococci have acquired resistance to any and every antibiotic in clinical use, the emergence of novel resistance mechanisms must always be a concern.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by grant AI46610 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger-Bächi, B., and M. L. Köhler. 1983. A novel site on the chromosome of Staphylococcus aureus influencing the level of methicillin resistance: genetic mapping. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 20:305-309. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers, H. F. 1995. In vitro and in vivo antistaphylococcal activities of L-695,256, a carbapenem with high affinity for the penicillin-binding protein PBP 2a. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:462-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers, H. F. 2003. Solving staphylococcal resistance to beta-lactams. Trends Microbiol. 11:145-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers, H. F., C. J. Hackbarth, T. A. Drake, M. G. Rusnak, and M. A. Sande. 1984. Endocarditis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in rabbits: expression of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in vivo and in vitro. J. Infect. Dis. 149:894-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers, H. F., M. Sachdeva, and S. Kennedy. 1990. Binding affinity for penicillin-binding protein 2a correlates with in vivo activity of beta-lactam antibiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 162:705-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Entenza, J. M., P. Hohl, I. Heinze-Krauss, M. P. Glauser, and P. Moreillon. 2002. BAL9141, a novel extended-spectrum cephalosporin active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in treatment of experimental endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:171-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fung-Tomc, J. C., J. Clark, B. Minassian, M. Pucci, Y. H. Tsai, E. Gradelski, L. Lamb, I. Medina, E. Huczko, B. Kolek, S. Chaniewski, C. Ferraro, T. Washo, and D. P. Bonner. 2002. In vitro and in vivo activities of a novel cephalosporin, BMS-247243, against methicillin-resistant and -susceptible staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:971-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerberding, J. L., C. Miick, H. H. Liu, and H. F. Chambers. 1991. Comparison of conventional susceptibility tests with direct detection of penicillin-binding protein 2a in borderline oxacillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2574-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghuysen, J. M. 1994. Molecular structures of penicillin-binding proteins and beta-lactamases. Trends Microbiol. 2:372-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goffin, C., and J. M. Ghuysen. 1998. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1079-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiramatsu, K., K. Asada, E. Suzuki, K. Okonogi, and T. Yokota. 1992. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the regulator region of mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). FEBS Lett. 298:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson, A. P., M. Warner, M. Carter, and D. M. Livermore. 2002. In vitro activity of cephalosporin RWJ-54428 (MC-02479) against multidrug-resistant gram-positive cocci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:321-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Lofdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim, D., and N. C. Strynadka. 2002. Structural basis for the beta lactam resistance of PBP2a from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:870-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryffel, C., A. Strassle, F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bächi. 1994. Mechanisms of heteroresistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:724-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song, M. D., M. Wachi, M. Doi, F. Ishino, and M. Matsuhashi. 1987. Evolution of an inducible penicillin-target protein in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by gene fusion. FEBS Lett. 221:167-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumita, Y., H. Nouda, K. Kanazawa, and M. Fukasawa. 1995. Antimicrobial activity of SM-17466, a novel carbapenem antibiotic with potent activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:910-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasz, A., H. B. Drugeon, H. M. de Lencastre, D. Jabes, L. McDougall, and J. Bille. 1989. New mechanism for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: clinical isolates that lack the PBP 2a gene and contain normal penicillin-binding proteins with modified penicillin-binding capacity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:1869-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomasz, A., S. Nachman, and H. Leaf. 1991. Stable classes of phenotypic expression in methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wada, A., and H. Watanabe. 1998. Penicillin-binding protein 1 of Staphylococcus aureus is essential for growth. J. Bacteriol. 180:2759-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, H. Z., C. J. Hackbarth, K. M. Chansky, and H. F. Chambers. 2001. A proteolytic transmembrane signaling pathway and resistance to beta-lactams in staphylococci. Science 291:1962-1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]