Abstract

TAN 1057-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli strains were selected to elucidate the mechanism of resistance and the mode of action of this dipeptide antibiotic. Cell-free translation with isolated ribosomes and S150 fractions from sensitive and resistant S. aureus strains demonstrated that alterations in the ribosomes contribute to the resistance of the bacteria.

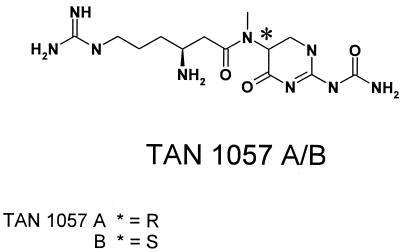

There is a critical need for new antibacterial compounds with no cross-resistance to commonly prescribed antibiotic classes (2, 15, 23). The antibiotic activity and the unique molecular architecture of TAN 1057 A/B prompted us to launch a chemical optimization program. TAN 1057 was first described by Hideo in 1989 (10) as a metabolite produced by the gram-negative soil bacterium Flexibacter sp. strain PK-74. The two diastereomers TAN 1057 A and B can be separated, but they spontaneously epimerize in aqueous solution (1, 3, 4, 14, 21, 22, 25). Therefore, all of the experiments described here were performed with a diastereomeric mixture (Fig. 1). TAN 1057 displays in vitro (5) and in vivo (9) antibacterial activity against staphylococci, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Its in vitro activity is excellent in synthetic medium and pure fetal calf serum (FCS), whereas in a standard assay medium such as Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth, the MICs increase 10- to 256-fold (e.g., the MICs against S. aureus P209 in AOAC and MH medium are 0.1 and 3.1 μg/ml, respectively) (3, 12). Preliminary mechanism-of-action studies revealed that TAN 1057 inhibits protein synthesis in whole-cell experiments and in cell-free translation assays (12). Further experiments demonstrated that the mechanism of action of TAN 1057 is complex. Cell-free translation is inhibited with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 4.5 μg/ml, and ribosome assembly is affected with almost equal potency (IC50, 9 μg/ml) (6, 7). Boeddeker et al. (3), reported that TAN 1057 inhibits protein synthesis in cellular assays in Escherichia coli and S. aureus and in cell-free translation assays derived from both bacteria, probably by inhibiting the peptidyltransferase activity of the ribosomes.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of the dipeptide antibiotic TAN 1057 A/B.

The purpose of our study was to select bacteria resistant to TAN 1057 as a tool with which to investigate if the mechanism of resistance is mediated by alterations in the translational apparatus. Resistance selection was performed with the clinical isolate S. aureus 133 (SA133-TANS, DSM11832) and the laboratory strain S. aureus RN4220 (SA4220-TANS) by the broth dilution method in FCS (13). The resulting isolates were the product of six serial transfers over a 6-day period with increasing TAN 1057 concentrations (SA-TANR-1 to -6). A stepwise increase in resistance was observed for both strains with MICs increasing by 1 or 2 dilution steps per day. At day 6, highly resistant strains for which the MICs were ≥64 μg/ml were observed (Table 1). Clinical E. coli isolates are normally not sensitive to TAN 1057. However, this constant increase in TAN 1057 resistance was also observed in experiments with TAN 1057-sensitive E. coli HN 818 (ΔacrAB), demonstrating that this phenotype is observed in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. To examine the stability of resistance, SA133-TANR-6 was subcultured in drug-free FCS for 6 days (SA133-TANR-6a). No MIC difference between these two strains was observed, indicating that the resistance phenotype observed is stable.

TABLE 1.

MICs for bacterial strains isolated during resistance selection

| Isolate | TAN 1057 MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus 133 | S. aureus RN 4220 | E. coli HN818 | |

| TANS | 0.125 | 0.06 | 4 |

| TANR-1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 8 |

| TANR-2 | 1 | 0.5 | 16 |

| TANR-3 | 2 | 1 | 32 |

| TANR-4 | 8 | 4 | 32 |

| TANR-5 | 32 | 16 | 64 |

| TANR-6 | >64 | 64 | 64 |

| TANR-6a | >64 | NDa | ND |

ND, not done.

Antibiotic susceptibilities of SA133-TANS and SA133-TANR-6a were determined for 19 reference compounds, including several translation inhibitors (Table 2). MICs of TAN 1057 increased >1,000-fold, and no significant change in susceptibility to any of the other compound tested was evident. This lack of cross-resistance indicates that TAN 1057 acts by a new mechanism.

TABLE 2.

MICs of different reference compounds for SA133-TANS and SA133-TANR-6a

| Compound | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| SA133-TANS | SA133-TANR-6a | |

| TAN 1057 | 0.1 | >100 |

| Erythromycin | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 4 |

| Linezolid | 4 | 2 |

| Streptomycin | 8 | 4 |

| Fusidic acid | 1 | 1 |

| Tetracycline | 4 | 4 |

| Neomycin | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Kanamycin | 2 | 1 |

| Ampicillin | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Penicillin G | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Methicillin | 2 | 4 |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 1 |

| Teicoplanin | 1 | 1 |

| Fosfomycin | 8 | 8 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 0.25 |

| Trimethoprim | 2 | 2 |

| Ethidium bromide | 8 | 4 |

All compounds were tested in ISO-Sensitest medium, except TAN-1057, which was tested in FCS.

In order to investigate if the mechanism of resistance is due to modifications in the bacterial translation machinery, cell-free S30 transcription-translation (TT) extracts were prepared from SA133-TANR strains and the precursor strain SA133-TANS and used for coupled cell-free TT experiments (16, 17). In these experiments, plasmid pKV48 was used as a template and incorporation of radioactive [35S]Met into the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase protein was measured by precipitation with potassium hydroxide, subsequent filtration, and detection of the filter-bound radioactivity in a scintillation counter (17). TAN 1057 inhibits TT of SA133-TANS extract with high potency (IC50, 1.45 μg/ml; Table 3). Extracts from strains isolated early during resistance selection were still sensitive, with IC50s between 1.28 and 1.78 μg/ml. Extracts isolated from SA133-TANR-5 (day 5) became approximately 13-fold resistant in TT experiments (IC50, 23.2 μg/ml). No further IC50 increase was detected for extracts isolated at day 6 (SA133-TANR-6 and -6a). In control TT experiments, no change in sensitivity was observed for the translation inhibitor erythromycin, with IC50s of 0.19 to 0.39 μg/ml for all extracts (SA133-TANS and SA133-TANR).

TABLE 3.

Inhibition by TAN 1057 and erythromycin of coupled cell-free TT of extracts derived from different TAN-sensitive and TAN-resistant strains

| Strains | Cell-free TT IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| TAN 1057 | Erythromycin | |

| SA133-TANS | 1.45 | 0.3 |

| SA133-TANR-1 | 1.4 | 0.19 |

| SA133-TANR-2 | 1.38 | 0.3 |

| SA133-TANR-3 | 1.28 | 0.31 |

| SA133-TANR-4 | 1.78 | 0.37 |

| SA133-TANR-5 | 23.2 | 0.37 |

| SA133-TANR6 | 15.4 | 0.19 |

| SA133-TANR-6a | 19.3 | 0.39 |

[35S]Met incorporated into chloramphenicol acetyltransferase was detected by precipitation with potassium hydroxide, subsequent filtration, and quantification of the filter-bound radioactivity in a scintillation counter. IC50 are mean values of at least two independent experiments.

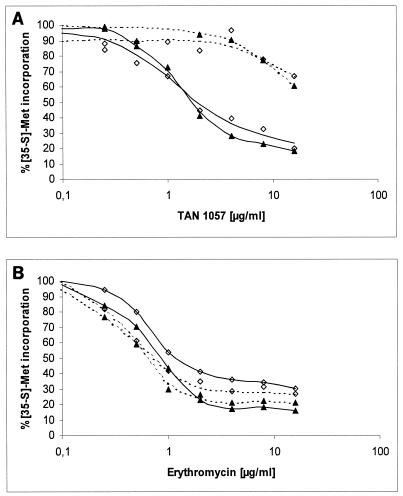

In order to identify the component responsible for maintaining TAN 1057 resistance in TT, S30 extracts from SA133-TANS and the final isolate SA133-TANR-6a were separated into S150 fractions (containing all of the soluble factors necessary for TT) and crude ribosomes (16, 17). Subsequently, TT experiments with various combinations of these S150 fractions and ribosomes were performed (Fig. 2A). Experiments in the absence of any inhibitor demonstrated that both S. aureus strains had comparable activities, and experiments in the presence of erythromycin indicated that both strains had comparable sensitivities to this control compound (Fig. 2B). All combinations of ribosomes and S150 fractions showed a dose-dependent decrease in activity in the presence of TAN 1057. TT was sensitive when ribosomes from SA133-TANS were used and became resistant when ribosomes from SA133-TANR-6a were tested, independently of the S150 fractions added. This suggests that the TAN 1057 resistance observed in the TT experiments results from alterations of the bacterial ribosome.

FIG. 2.

Coupled cell-free TT assays with ribosomes (70S) and S150 fractions derived from SA133-TANS and SA133-TANR-6a were used to test for resistance to TAN 1057 (A) and erythromycin (B). Dotted lines, ribosomes isolated from SA133-TANR-6a; solid lines, ribosomes from SA133-TANS; diamonds, S150 fraction from SA133-TANR-6a; triangles, S150 fraction from SA133-TANS.

TAN 1057 resistance is complex. Boeddeker et al. (3) selected TAN 1057-resistant S. aureus by a one-step selection method in solid MH medium. Many of the colonies that grew at four times the MIC were small and grew slowly. At least one strain was resistant to TAN 1057 when tested in a liquid MIC test, with values increasing by a factor of >50 compared to the wild-type S. aureus strain. However, wild-type and mutant extracts supported cell-free poly(U)-dependent poly(Phe) synthesis at similar rates, indicating that the translation machinery was not altered in this resistant strain. The authors concluded that alterations in a dipeptide transport mechanism might be responsible for this increase in resistance, because TAN 1057 resembles a dipeptide molecule and its activity can be antagonized in cellular assays by addition of dipeptides (3, 12). In our study, we used a multistep selection procedure over a 6-day period in liquid FCS. Different resistance mechanisms might contribute to the phenotypes observed in our experiments. Early, low-level resistance might be due to alterations in dipeptide transporters or alterations in efflux pumps, e.g., norA, as observed for quinolones (8, 11, 19). We have evidence that norA overexpression does not contribute to TAN 1057 resistance, because resistant strain SA133-TANR-6a is sensitive to the norA substrates ciprofloxacin and ethidium bromide (Table 2). Since norA is not the only efflux pump in S. aureus, further investigations are needed to demonstrate if other efflux pumps are involved during early development of resistance to TAN 1057. The early, low-level resistance mechanism is followed by an alteration in the ribosome. Ribosomal-protein genes are the most likely targets for these mutations, because these proteins are encoded only once in the genome and one mutation would lead to 100% mutated ribosomes. Another possible explanation for a stepwise MIC increase is the occurrence of mutations in the rRNA, as reported for the oxazolidinones. In Enterococcus faecalis and E. faecium, the level of resistance to linezolid is correlated with the number of 23S rRNA genes containing a G2576U mutation, providing one example for a clear gene dosage effect (6, 18, 20, 24). Five rRNA gene copies have been described in S. aureus. If one of these genes has been mutated during TAN 1057 selection, presumably 15 to 20% of the ribosome population would be resistant. Mutations of further rRNA genes would lead to further increases in the mutated ribosome population and, consequently, might lead to stepwise increases in resistance. However, these stepwise increases in resistance were not observed in the cell-free translation and further experiments are necessary to investigate the effect of TAN 1057 on protein synthesis in whole-cell assays with TANS and TANR strains.

In summary, a stepwise increase in resistance was observed during TAN 1057 resistance selection in different bacterial species, and cell-free TT assays revealed that alterations in the ribosomes contribute to the bacterial resistance observed.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the excellent technical assistance of Martin Groth (Pharma Research, Bayer AG). We thank Hiroshi Nikaido (University of California, Berkeley) for providing E. coli strain HN818, Regine Hakenbeck (University of Kaiserslautern, Kaiserslautern, Germany) for plasmid pKV48, Guy Hewlett (Pharma Research, Bayer AG) for critical reading of the manuscript, and Harald Labischinski (Pharma Research, Bayer AG) for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, N., and J. Krüger. 2002. Towards a library synthesis of the natural dipeptide antibiotic TAN 1057 A,B. Molecules 7:469-474. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger-Bachi, B. 2002. Resistance mechanisms of gram-positive bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeddeker, N., G. Bahador, C. Gibbs, E. Mabery, J. Wolf, L. Xu, and J. Watson. 2002. Characterization of a novel antibacterial agent that inhibits bacterial translation. RNA 8:1120-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brands, M., R. Endermann, R. Gahlmann, J. Kruger, and S. Raddatz. 2003. Dihydropyrimidinones—a new class of anti-staphylococcal antibiotics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brands, M., R. Endermann, R. Gahlmann, J. Kruger, S. Raddatz, J. Stoltefuss, V. N. Belov, S. Nizamov, V. V. Sokolov, and A. de Meijere. 2002. Novel antibiotics for the treatment of gram-positive bacterial infections. J. Med. Chem. 45:4246-4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champney, W. S. 2001. Bacterial ribosomal subunit synthesis: a novel antibiotic target. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 1:19-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champney, W. S., J. Pelt, and C. L. Tober. 2001. TAN-1057A: a translational inhibitor with a specific inhibitory effect on 50S ribosomal subunit formation. Curr. Microbiol. 43:340-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier, B., Q. C. Truong-Bolduc, X. Zhang, and D. C. Hooper. 2001. A mutation in the 5′ untranslated region increases stability of norA mRNA, encoding a multidrug resistance transporter of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:2367-2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funabashi, Y., S. Tsubotani, K. Koyama, N. Katayama, and S. Harada. 1993. A new anti-MRSA dipeptide, TAN-1057 A. Tetrahedron 49:13-28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hideo, O. March1994. Antibiotics TAN-1057 patent EP 339596.

- 11.Hooper, D. C. 2001. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobials: focus on fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 1):S9-S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katayama, N., S. Fukusumi, Y. Funabashi, T. Iwahi, and H. Ono. 1993. TAN-1057 A-D, new antibiotics with potent antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Taxonomy, fermentation and biological activity. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 46:606-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, M. J., H. J. Yun, J. W. Kang, S. Kim, J. H. Kwak, and E. C. Choi. 2003. In vitro development of resistance to a novel fluoroquinolone, DW286, in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1011-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin, P. S., and A. Ganesan. 2000. Assembly of the TAN-1057 A/B heterocycle from a dehydroalanine precursor. Synthesis 14:2127-2130. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livermore, D. M. 2003. Bacterial resistance: origins, epidemiology, and impact. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:S11-S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller, M., and G. Blobel. 1984. In vitro translocation of bacterial proteins across the plasma membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7421-7425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray, R. W., E. P. Melchior, J. C. Hagadorn, and K. R. Marotti. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus cell extract transcription-translation assay: firefly luciferase reporter system for evaluating protein translation inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1900-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray, R. W., R. D. Schaadt, G. E. Zurenko, and K. R. Marotti. 1998. Ribosomes from an oxazolidinone-resistant mutant confer resistance to eperezolid in a Staphylococcus aureus cell-free transcription-translation assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:947-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng, E. Y. W., M. Trucksis, and D. C. Hooper. 1994. Quinolone resistance mediated by norA: physiologic characterization and relationship to flqB, a quinolone resistance locus on the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1345-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prystowsky, J., F. Siddiqui, J. Chosay, D. L. Shinabarger, J. Millichap, L. R. Peterson, and G. A. Noskin. 2001. Resistance to linezolid: characterization of mutations in rRNA and comparison of their occurrences in vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2154-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sokolov, V. V., S. I. Kozhushkov, S. Nikolskaya, V. N. Belov, M. EsSayed, and A. deMeijere. 1998. Total synthesis of TAN-1057 A/B, a new dipeptide antibiotic from Flexibacter sp. PK-74. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 777-783.

- 22.Williams, R. M., C. Yuan, V. J. Lee, and S. Chamberland. 1998. Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of TAN-1057A/B analogs. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 51:189-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood, M. J., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 2003. Microbial resistance: bacteria and more. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:S2-S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong, L., P. Kloss, S. Douthwaite, N. M. Andersen, S. Swaney, D. L. Shinabarger, and A. S. Mankin. 2000. Oxazolidinone resistance mutations in 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli reveal the central region of domain V as the primary site of drug action. J. Bacteriol. 182:5325-5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan, C. G., and R. M. Williams. 1997. Total synthesis of the anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus peptide antibiotics TAN-1057A-D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:11777-11784. [Google Scholar]