Abstract

Purpose

Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters has been found in head and neck squamous carcinoma (HNSCC) and other solid tumors. We evaluated these alterations in pretreatment salivary rinses from HNSCC patients by using real-time quantitative methylation-specific PCR (Q-MSP).

Experimental Design

Pretreatment saliva DNA samples from HNSCC patients were evaluated for patterns of hypermethylation by using Q-MSP. Target tumor suppressor gene promoter regions were selected based on a previous study describing a screening panel for HNSCC in a high-risk population subjects. The selected genes were: DAPK, DCC, MINT-31, TIMP-3, p16, MGMT, CCNA1.

Results

We analyzed the panel in a cohort of 61 HNSCC patients. Thirty-three of the analyzed patients (54.1%) showed methylation of at least one of the selected genes in the saliva DNA. Pretreatment methylated saliva DNA was not significantly associated with tumor site (P = 0.209) nor clinical stage (P = 0.299). However, local disease control and overall survival were significantly lower in patients presenting hypermethylation in saliva rinses (P = 0.010 and P = 0.015, respectively). Multivariate analysis confirmed that this hypermethylation pattern remained as an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence (HR = 12.2; 95% CI = 1.8–80.6; P = 0.010) and overall survival (HR = 2.8; 95% CI = 1.2–6.5; P = 0.016).

Conclusions

We were able to confirm an elevated rate of promoter hypermethylation in HNSCC saliva of patients by using a panel of gene promoters previously described as methylated specifically in HNSCC. Detection of hypermethylation in pretreatment saliva DNA seems to be predictive of local recurrence and overall survival. This finding has potential to influence treatment and surveillance of HNSCC patients.

Introduction

The use of molecular markers in body fluids for cancer detection has been explored with the intent to improve screening accuracy and cost effectiveness. Body fluids can potentially carry whole cells, as well as protein, DNA, and RNA species that allow for detection of cellular alterations related to cancer. Examples of relevant body fluids used for detection include: analysis of sputum for lung cancer diagnosis (1, 2) urine for urologic tumors (3) saliva for head and neck squamous carcinoma (HNSCC; refs. 4–6); breast fluid (7). The feasibility of cancer detection in body fluids also opens the potential for surveillance after treatment. Molecular detection techniques have the potential to predict tumor recurrence before clinical symptoms or physical exam changes. This would then influence treatment choice and surveillance strategies.

An epigenetic pathway of transcriptional inactivation for many tumor suppressor genes (TSG) includes CpG island hypermethylation within promoter regions (8, 9). This pathway has been identified in many different cancers and recent studies have focused on promoter hypermethylation in HNSCC (10, 11). Promoter hypermethylation in tissue samples can be detected by using quantitative methylation-specific PCR (Q-MSP), this real-time PCR methodology allows a more objective, robust, and rapid assessment of promoter methylation status. The ability to quantify methylation provides the potential for determination of a threshold level of methylation to improve sensitivity and specificity in detection of tumor-specific signal (12–14).

The detection of DNA methylation in body fluids also has the potential to distinguish high-risk subjects that harbor occult cancers and have a higher risk for development of cancer in urologic, lung, and other cancers. Our group has developed a panel for detection of HNSCC by evaluation of salivary rinses from these patients (15). Here, we conducted a study to determine if a previously reported panel of promoter hypermethylation markers would correlate with clinical outcomes in prospectively studied patient cohort by detection of epigenetic changes associated with HNSCC in pretreatment salivary rinses.

Materials and Methods

Tissue samples

Samples were obtained from HNSCC patients presenting with a previously untreated squamous cell carcinoma from the oral cavity, larynx, or pharynx. Patients were evaluated and enrolled in a protocol from 1994 to 2003 in the Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore. Salivary rinse samples from these patients were collected before any cancer treatment, while the primary tumor was present. Patients were selected for candidacy for the study on basis of ability to provide adequate tumor sample, blood, salivary rinses, and availability for long-term follow-up.

Salivary rinses were obtained by brushing the oral cavity and oropharyngeal surfaces with an exfoliating brush followed by rinse and gargle with 20 mL normal saline solution. Cellular material from the brushing was released into the saline rinse and centrifuged to obtain a cell pellet after supernatant was discarded.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all enrolled subjects.

DNA extraction

DNA obtained from tumor, salivary rinses, and serum samples was extracted by digestion with 50 μg/mL proteinase K (Boehringer) in the presence of 1% SDS at 48°C overnight, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation.

Bisulfite treatment

DNA from tissue samples was subjected to bisulfite treatment, as described previously (16). Briefly, 2 μg of genomic DNA was denatured in 0.2 mol/L of NaOH for 20 minutes at 50°C. The denatured DNA was diluted in 500 μL of freshly prepared solution of 10 mmol/L hydroquinone and 3 mol/L of sodium bisulfite and incubated for 3 hours at 70°C. After incubation, the DNA sample was desalted through a column (Wizard DNA Clean-Up System; Promega), treated with 0.3 mol/L of NaOH for 10 minutes at room temperature and precipitated overnight with ethanol. The bisulfite-modified genomic DNA was resuspended in 120 μL of H2O and stored at −80°C.

Quantitative methlyation-specific PCR

The bisulfite-modified DNA was used as a template for fluorescence-based real-time PCR, as previously described (17). In brief, primers and probes were designed to specifically amplify the bisulfite-converted DNA for the ACTB gene and all genes of interest (primers and probes sequences are available on previous publication; 15). The ratios between the values of the gene of interest and the internal reference gene (ACTB), was obtained by Taqman analysis taking into account the PCR efficiency. Results were used as a measure of the relative quantity of methylation in a particular sample (value for the gene of interest/value for the reference gene × 100). Fluorogenic PCR reactions were carried out in a reaction volume of 20 μL consisting of 600 nmol/L of each primer; 200 μmol/L of probe; 0.75 U of platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen); 200 μmol/L of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 200 nmol/L of ROX Dye reference (Invitrogen); 16.6 mmol/L of ammonium sulfate; 67 mmol/L of Trizma (Sigma); 6.7 mmol/L of magnesium chloride; 10 mmol/L of mercaptoethanol; and 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide. Three microliters of treated DNA solution were used in each real-time MSP reaction. Amplifications were carried out in 384-well plates in a 7900 Sequence Detector System (Perkin–Elmer Applied Biosystems). Thermal cycling was initiated with a first denaturation step at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C or 62°C for 1 minute. Leukocytes from a healthy individual were methylated in vitro with excess SssI methyltransferase (New England Biolabs) to generate completely methylated DNA, and serial dilutions of this DNA were used for constructing the calibration curves on each plate. Each reaction was done in triplicate, the average of the triplicate was considered for analysis. Results for Q-MSP was analyzed considering the quantity of methylation (normalized by ACTB) and considering methylation as a binary event, in which any quantity of methylation in a sample would be considered as positive.

Target gene selection

Genes selected for this study, came from a study previously done by the authors to develop a panel for HNSCC detection in body fluids. The genes able to detect HNSCC in saliva rinse and included in this study were: DAPK, DCC, MINT-31, TIMP-3, p16, MGMT, and Cyclin-A1 (15).

HPV analysis

Specific primers and probes have been designed to amplify the E6 and E7 regions of HPV 16. HPV 16 E6 forward primer, 5′-TCAGGACCCACAGGAGCG-3′,. HPV 16 E6 reverse primer, 5′-CCTCACGTCGCAGTAACTGT-TG-3′, HPV 16 E6 Taqman probe, 5′-(FAM)-CCCAGA-AAGTTACCACAGTTATGCACAGAGCT-(TAMRA)-3′, HPV 16 E7 forward primer, 5′-CCGGACAGAGCCCATTACAA-3′, HPV 16 E7 reverse primer, 5′-CGAATGTCTACGTGT-GTGCTTTG-3′, HPV 16 E7 Taqman probe, 5′-(FAM)-CGCA-CAACCGAAGCGTAGAGTCACACT-(TAMRA)-3′, β-actin forward primer, 5′-TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA-3′, β-actin reverse primer, 5′-CAGCGGAACCGCTCATTGC-CAATGG-3′, β-actin Taqman probe, 5′-(FAM)-ATGCCCTC-CCCCATGCCATCCTGCGT-(TAMRA)-3′. All the samples were run in duplicate. Primers and probes to a housekeeping gene (β-actin) were run in duplicate and parallel to normalize input DNA. Samples in which 2 results were not concordant were repeated twice in duplicate and were usually due to failed PCR in one of the initial reactions. Each reaction was run 50 cycles. By using serial dilutions, standard curves were developed for the HPV 16 viral copy number by using CaSki (American Type Culture Collection) cell line genomic DNA, known to have 600 copies/genome (6.6 pg of DNA/genome). Standard curves were developed for HPV 16 E6 and E7, using serial dilutions of DNA extracted from CaSki cells with 50,000, 5,000, 500, 50, and 5 pg of DNA. Standard curves were developed as well for the β-actin housekeeping gene (2 copies/genome), using the same serial dilutions of the CaSki genomic DNA. This additional step allowed for relative quantification of the input DNA level and final quantity as the number of viral copies/genome/cell. HPV copy number more than 0.1 copy/cell for tumor samples was regarded as positive. For saliva samples, any amplified sample with HPV E6 or E7 amplification with a control β-actin amplification of 10 ng was regarded as positive (18).

Statistical analysis

Hypermethylation of each gene was treated as a binary variable (methylation vs. no methylation) by dichotomizing each gene at zero.

Descriptive analysis was done to show the distribution of the population and the statistical comparisons by using Fisher’s exact test or exact χ2 test as appropriate.

The survival analyses were done by using the Kaplan–Meier method and survival distributions were compared by using the log-rank test. The local disease control time was defined as the interval between the date of initial treatment and diagnosis of local recurrence. Patients experiencing death from all causes were considered as failures as well. Those who remained alive and did not have documented local recurrence were censored at their last follow-up. The overall survival interval was defined as the interval between the date of the initial treatment and death or last follow-up. The model building procedures involved the use of univariate followed by multivariable analyses. The Cox proportional hazards model was applied to assess the independent prognostic effect of the hypermethylation pattern by using the full panel (TIMP3, MGMT, MINT31, CyA1, DCC, DAPK, p16) in pretreatment saliva on local recurrence or death, with adjustment for potential confounding factors including HPV status, tumor site, pathologic T stage, nodal status, extracapsular spread, margins, lymphvascular invasion, perineural invasion, and postoperative radiotherapy. Adjusted HR were estimated along with 95% CI. The proportional hazards assumption was shown by creating a time-dependent covariate with the interaction of log (time) in the model for each covariate and testing its significance. As types I and II errors were of concern with these analyses, we made no adjustments for multiple comparisons (19, 20). All tests were 2-sided with statistical significance determined at P value less than 0.05. The analyses were done with SPSS (version 15.0, SPSS Inc.).

Results

Sixty-one patients were included in this study (Table 1). HNSCC patients were mainly males (82.0%), Caucasians (73.8%) with median age of 58.2 years (range 32–84 years). Alcohol or tobacco consumption (current or past) were reported by 72.5% and 84.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinicopathologic data overall and by promoter hypermethylation status on pretreatment saliva by using the full panel

| Characteristics | Overall, n (%) | Full panel saliva

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmethylated, n (%) | Methylated, n (%) | |||

| Age | ||||

| <60 years | 36 (59.0) | 17 (60.7) | 19 (57.6) | 0.804 |

| ≥60 years | 25 (40.1) | 11 (39.3) | 14 (42.4) | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 45 (73.8) | 19 (67.9) | 26 (78.8) | |

| African-American | 13 (21.3) | 9 (32.1) | 4 (12.1) | 0.060 |

| Other | 3 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50 (82.0) | 25 (89.3) | 25 (75.8) | 0.171 |

| Female | 11 (18.0) | 3 (10.7) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | 14 (27.5) | 7 (28.0) | 7 (26.9) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 37 (72.5) | 18 (72.0) | 19 (73.1) | |

| Tobacco consumption | ||||

| No | 9 (15.3) | 4 (14.8) | 5 (15.6) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 50 (84.7) | 23 (85.2) | 27 (84.4) | |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Oral cavity | 30 (49.2) | 11 (39.3) | 19 (57.6) | |

| Oropharynx | 19 (31.1) | 9 (32.1) | 10 (30.3) | 0.209 |

| Larynx/hypopharynx | 12 (19.7) | 8 (28.6) | 4 (12.1) | |

| HPV | ||||

| Negative | 43 (70.5) | 19 (67.9) | 24 (72.7) | 0.678 |

| Positive | 18 (29.5) | 9 (32.1) | 9 (27.3) | |

| pT stage | ||||

| pT1/T2 | 33 (55.0) | 18 (64.3) | 15 (46.9) | 0.176 |

| pT3/T4 | 27 (45.0) | 10 (35.7) | 17 (53.1) | |

| pN stage | ||||

| pN0 | 26 (44.8) | 13 (46.4) | 13 (43.3) | 0.813 |

| pN+ | 32 (55.2) | 15 (53.6) | 17 (56.7) | |

| Extracapsular spread | ||||

| No | 36 (64.3) | 18 (64.3) | 18 (64.3) | 1.000 |

| Yes | 20 (35.7) | 10 (35.7) | 10 (35.7) | |

| Margins | ||||

| Negative | 34 (66.7) | 18 (69.2) | 16 (64.0) | 0.692 |

| Positive | 17 (33.3) | 8 (30.8) | 9 (36.0) | |

| Lymphvascular invasion | ||||

| No | 40 (78.4) | 21 (91.3) | 19 (67.9) | 0.084 |

| Yes | 11 (21.6) | 2 (8.7) | 9 (32.1) | |

| Perineural invasion | ||||

| No | 43 (87.8) | 21 (91.3) | 22 (84.6) | 0.671 |

| Yes | 6 (12.2) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (15.4) | |

Primary tumor sites included: oral cavity, 30 cases (49.2%); oropharynx, 19 (31.1%); and larynx/hypopharynx, 12 (19.7%). HPV DNA was found in 18 cases (29.5%). Pathologic clinical stage at diagnosis was pT1/pT2 in 33 cases (54.1%) and pT3/pT4 in 27 (44.3%); and pN0 in 26 cases (42.6%), pN+ in 32 (52.5%), among those 20 cases (32.8%) presented with extracapsular spread. All patients underwent surgical resection in which 38 (62.3%) underwent postoperative radiotherapy. Positive or close (<5 mm) margins were noted in 17 cases (27.9%) and lymphvascular invasion in 11 cases (21.6%) among 51 patients with data available. Perineural invasion was present in 6 cases (12.2%) among 49 patients with this data available.

Promoter hypermethylation pattern of the 7 selected genes was tested in the primary tumor and pretreatment saliva. Fifty-nine primary tumors (96.7%) had hypermethylation of at least 1 gene of the panel. Using 10 selected combinations of the previously reported hypermethylated gene panel for HNSCC detection (15), the hypermethylation detection rate in pretreatment salivary rinses varies from 36.1% to 54.1% depending on the panel tested, with the highest value for the full panel (hypermethylation of at least 1 gene from the panel—54.1%).

Clinic-pathologic characteristics in this cohort of patients did not show any statistically significant difference across unmethylated and methylated pretreatment saliva DNA (Table 1). However, we noticed a trend toward a higher proportion of lymphvascular invasion and lower proportion of patients with postoperative radiation therapy in the methylated cohort, albeit the differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 1).

The median follow-up period for this cohort of patients was 2.1 years (range=1 day–9.8 years). Recurrences as ofthis analysis occurred in 22 cases (36.1%), including local recurrence in 11 cases (18.0%); regional in 8 (13.1%) and distant in 8 (13.1%). Recurrences included 5 patients with multisite recurrences (8.2%). Local recurrences occurred in a median period of 15.7 months after initial treatment; with 81.8% of recurrences diagnosed before 2 years of follow-up.

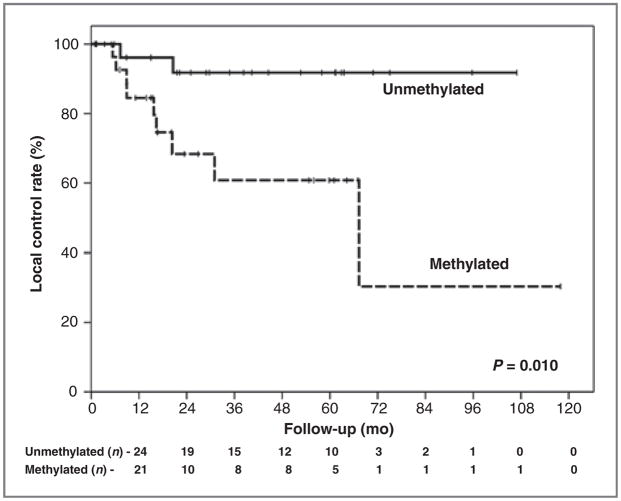

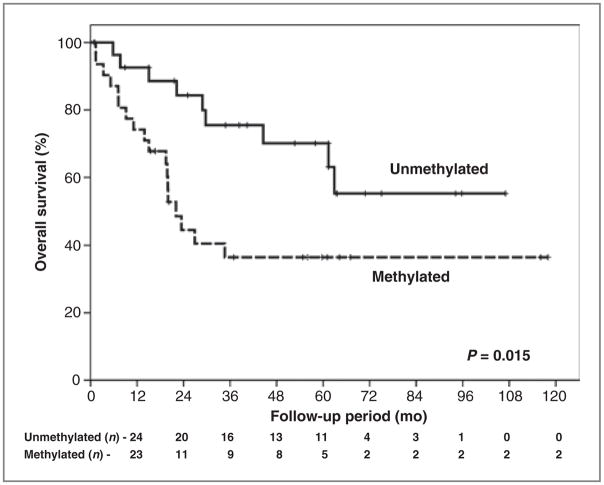

Local disease control rate at 5 years was 77.4%, varying from 60.8% for cases with hypermethylation detected in pretreatment saliva rinses to 91.8% for the patients without hypermethylation (P = 0.010; Fig. 1). Overall survival at 5 years was 52.5%, varying from 36.5% for cases with pre-treatment saliva rinse hypermethylation to 70.1% for cases without pretreatment salivary rinse methylation (P = 0.015; Fig. 2). For combined events (local recurrence plus death) hypermethylation in saliva was associated also with a worse prognosis (P = 0.008; Supplementary Fig.).

Figure 1.

Local control rates according to the hypermethylation pattern on saliva pretreatment (full panel).

Figure 2.

Overall survival according to the hypermethylation pattern on saliva pretreatment (full panel).

In univariate analysis, tumor site was related to local control (P = 0.002) in addition to saliva hypermethylation. For overall survival, advanced pT stage was associated with poorer prognosis (P = 0.023; Table 2). Using the top 10 combinations from our previously reported gene panel, we found that all tested combinations showed statistically significant associations of pretreatment salivary rinse methylation with poorer local control; and 3 of 10 combinations were found to be significantly associated with poorer overall survival (Table 3).

Table 2.

Local control and overall survival rates according to the clinical variables

| Variables | Categories | 5-year local control (%) | P | 5-year overall survival (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <60 years | 79.2 | 0.447 | 66.9 | 0.065 |

| ≥60 years | 69.3 | 28.1 | |||

| Gender | Male | 77.7 | 0.373 | 53.3 | 0.899 |

| Female | 74.1 | 51.9 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | No | 63.3 | 0.254 | 57.1 | 0.681 |

| Yes | 85.9 | 58.1 | |||

| Tobacco consumption | No | 76.2 | 0.755 | 77.8 | 0.074 |

| Yes | 76.7 | 48.8 | |||

| Tumor site | Oral cavity | 57.1 | 0.002 | 49.2 | 0.527 |

| Oropharynx | 100.0 | 43.5 | |||

| Larynx/hypopharynx | 100.0 | 83.3 | |||

| HPV | Negative | 80.1 | 0.457 | 54.3 | 0.496 |

| Positive | 72.1 | 47.5 | |||

| pT stage | pT1/T2 | 81.9 | 0.859 | 63.8 | 0.023 |

| pT3/T4 | 74.1 | 41.4 | |||

| pN stage | pN0 | 85.9 | 0.556 | 56.9 | 0.548 |

| pN+ | 73.5 | 51.4 | |||

| Extracapsular spread | No | 83.1 | 0.598 | 56.5 | 0.447 |

| Yes | 68.2 | 45.4 | |||

| Margins | Negative | 74.6 | 0.271 | 55.6 | 0.919 |

| Close/positive | 78.6 | 48.7 | |||

| Lymphvascular invasion | No | 82.1 | 0.228 | 57.5 | 0.041 |

| Yes | 34.3 | 25.5 | |||

| Perineural invasion | No | 75.5 | 0.769 | 56.7 | 0.148 |

| Yes | 75.0 | 16.7 | |||

| Postoperative radiotherapy | No | 79.0 | 0.726 | 44.0 | 0.070 |

| Yes | 76.7 | 57.6 |

Table 3.

Local control and overall survival rates according to the promoter hypermethylation pattern on saliva pretreatment

| Panel | Hypermethylation pattern | 5-year local control (%) | P | 5-year overall survival (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIMP3+MGMT+MINT31+CCNA1+DCC+ DAPK+p16 (full panel) | Unmethylated | 91.8 | 0.010 | 70.1 | 0.015 |

| Methylated | 60.8 | 36.5 | |||

| CCNA1+DCC+DAPK+p16 | Unmethylated | 92.8 | 0.001 | 66.7 | 0.017 |

| Methylated | 51.9 | 31.7 | |||

| MINT31+CCNA1+DCC+DAPK+p16 | Unmethylated | 92.5 | 0.002 | 65.5 | 0.045 |

| Methylated | 55.2 | 34.9 | |||

| MINT31+MGMT+CCNA1+p16 | Unmethylated | 92.8 | 0.001 | 62.9 | 0.164 |

| Methylated | 53.4 | 37.4 | |||

| MINT31+CCNA1+DCC+p16 | Unmethylated | 88.2 | 0.004 | 61.4 | 0.177 |

| Methylated | 60.0 | 35.6 | |||

| CCNA1+DCC+p16 | Unmethylated | 88.7 | 0.002 | 62.5 | 0.084 |

| Methylated | 57.4 | 31.7 | |||

| MINT31+CCNA1+DAPK+p16 | Unmethylated | 93.1 | <0.001 | 67.8 | 0.009 |

| Methylated | 47.9 | 28.1 | |||

| CCNA1+DCC+DAPK | Unmethylated | 86.6 | 0.029 | 62.7 | 0.080 |

| Methylated | 57.9 | 34.8 | |||

| MINT31+CCNA1+DCC+DAPK | Unmethylated | 88.9 | 0.009 | 63.4 | 0.086 |

| Methylated | 58.5 | 36.7 | |||

| MINT31+MGMT+CCNA1 | Unmethylated | 92.8 | 0.001 | 62.1 | 0.164 |

| Methylated | 53.4 | 37.4 | |||

| MGMT+CCNA1+p16 | Unmethylated | 93.1 | <0.001 | 63.3 | 0.079 |

| Methylated | 50.0 | 34.0 |

Multivariate survival analysis models showed that detection of hypermethylation in pretreatment salivary rinses remained as an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence (HR = 12.2; 95% CI = 1.8–80.6; P = 0.010) after adjustment for the best-known prognostic factors (e.g., tumor site, HPV, nodal status, extracapsular spread, margins, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and postoperative radiotherapy). HPV was shown to be an independent prognostic factor for local recurrence as well (HR = 23.1; 95% CI = 2.8–189.0; P = 0.003) and pT stage (HR = 5.6; 95% CI = 1.3–25.2; P = 0.024). With the adjustment for the above noted confounders, the independent prognostic factors for overall survival were pT stage (HR = 3.3; 95% CI = 1.4–7.4; P = 0.005), postoperative radiotherapy (HR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.2–0.8; P = 0.017) and hypermethylation in pre-treatment saliva rinses (HR = 2.8; 95% CI = 1.2–6.5; P = 0.016; Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for local control and overall survival

| Categories | HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local control (model adjusted by tumor site) | ||||

| HPV | Negative | 1 | Ref. | 0.003 |

| Positive | 23.1 | 2.8–189.0 | ||

| Methylation pattern on saliva (full panel) | Unmethyalated | 1 | Ref. | 0.010 |

| Methylated | 12.2 | 1.8–80.6 | ||

| pT stage | pT1/T2 | 1 | Ref. | 0.024 |

| pT3/T4 | 5.6 | 1.3–25.2 | ||

| Overall survival (model adjusted by HPV) | ||||

| pT stage | pT1/T2 | 1 | Ref. | 0.005 |

| pT3/T4 | 3.3 | 1.4–7.4 | ||

| Postoperative radiotherapy | No | 1 | Ref. | 0.017 |

| Yes | 0.4 | 0.2–0.8 | ||

| Methylation pattern on saliva (full panel) | Unmethyalated | 1 | Ref. | 0.016 |

| Methylated | 2.80 | 1.2–6.5 | ||

Discussion

Aberrant promoter hypermethylation has been proposed as a means for detection of tumor-specific cells in body fluids and exfoliated cells in solid tumors, including HNSCC. In a previous study, we have evaluate a large sample size of both controls and HNSCC patients by using an expanded panel of methylated promoter regions to determine the ability of Q-MSP to detect tumor-specific promoter methylation in serum and salivary rinses. We used salivary samples obtained from rinses and brushing healthy individuals as normal control tissue to obtain a broad representation of epithelial cells from the upper aerodigestive tract. Given the sensitivity of the Q-MSP technique used to detect the presence of methylated alleles in a background of normal at a threshold of 1/1,000 to 1/10,000, this strategy allowed us to define methylated genes that were highly specific for tumor, and rarely or never present in any of the aerodigestive sites that shed cells in salivary rinses. From the initial screening of 21 genes for salivary rinses, ultimately 7 genes were selected as part of a panel to distinguish salivary rinses from HNSCC patients and healthy controls. A combination of 3 or 4 genes is able to provide a sensitivity of cancer detection ranging from 24.0% to 35.1% with a specificity ranging from 90.0% to 97.1% (21).

Those findings confirmed that detection of tumor-specific promoter hypermethylation is feasible in body fluids (1, 5, 22) and the Q-MSP is well adapted into a high throughput format (12–14).

In general, we were able to define a panel for HNSCC detection with a high specificity but accompanied by a low sensitivity. However, we were able to define panels with high sensitivity and low specificity, which have potential use for surveillance after treatment or in a high risk population. We decide to test the hypothesis that pretreatment salivary rinses may be associated with clinical outcome and evaluate the utility of our panel in predicting local recurrence in HNSCC patients.

Righini and colleagues evaluated a cohort of 90 patients for the utility of methylation detection in saliva pre- and posttreatment, among the 22 patients suitable for follow-up. Hypermethylation on postoperative salivary rinses were analyzed, including 6 patients with recurrence. Among those, 5 patients showed hypermethylation in postoperative salivary rinses, only 1 case without recurrence showed methylation in saliva (23).

In this study, the detection of hypermethylation in pre-treatment salivary rinses was significantly related to local control and overall survival. Interestingly, hypermethylated HNSCC salivary rinses were not associated with tumor site or clinical stage and were noted to be an independent risk factor for local control and overall survival in the multivariate analysis.

The prognostic significance of hypermethylation in pretreatment salivary rinses is related to a higher concentration of methylated signal in exfoliated cells, independent of tumor stage or site, and therefore is unlikely to be related to tumor volume per se. However, there are multiple, possibly complementary explanations for this association. Aggressive tumors with poorer prognosis may undergo increased rate of mechanical dissociation or shedding into salivary rinses. Those tumors with a higher burden of epigenetic alteration would be more frequently detected in salivary rinses, and may have a more aggressive behavior. Other explanantions include the phenomenon of lateral clonal expansion, in which premalignant clonal patches expand well beyond primary tumor location, resulting in a larger surface area of epigenetically altered cells to shed into the saliva, and also may predispose to development of recurrent tumors from adjacent premalignant cells.

To further explore, the possibility that detection of promoter hypermethylation in salivary rinses may be due to detection of aberrant, clonal mucosal patches, we examined the correlation of gene-specific methylation in salivary rinses and primary tumors. We found that for 2 cases in which primary tumor showed no methylation, the corresponding salivary rinse did not show promoter methylation; for the 59 cases in which primary tumor was methylated, 33 (55.9%) presented with methylation of 1 or more methylated genes in the corresponding salivary rinse. We noted that a small proportion of salivary rinses displayed promoter hypermethylation without methylation of that specific gene in the corresponding primary tumor, ranging from up to 14% in the case of CCNA1, and less than 10% for all other genes (Supplementary Tables).

We also noted that the independent prognostic association of promoter hypermethylation with clinical outcome was based primarily on oral cavity cancers, which comprised the largest site of origin in this study. This is likely a reflection of the recruitment of patients via a surgical out-patient clinic, and a more definitive conclusion about the prognostic significance of salivary rinse promoter hypermethylation in oropharyngeal and laryngeal primary HNSCC treated with nonsurgical therapies would require a larger study enriched for these patient populations.

We were able to confirm an elevated rate of promoter hypermethylation detected in HNSCC patient salivary rinses by using a panel of gene promoters previously described as methylated in HNSCC but not in control subjects. In addition, detection of hypermethylation in pretreatment saliva DNA is associated with local recurrence. This has implication for further study about the mechanism of this observation but also may have practical applications for increasing intensity of surveillance, or using adjunctive therapy for local control in patients with promoter hypermethylation in pretreatment salivary rinses.

Translational Relevance.

This manuscript details a promoter methylation-based assay panel, that is, independently associated with local recurrence and survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. This assay panel may have utility in identification of patients at high risk for recurrence that may benefit from adjuvant therapy to reduce risk of local recurrence and intensive surveillance to detect recurrence at an earlier stage.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support

This work was supported by a SPORE grant—P50 CA96784.

J.A. Califano is a Damon Runyon-Lilly Clinical Investigator supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI-#9) and a Clinical Innovator Award from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute. A.L. Carvalho had a Coordenação de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior scholarship (CAPES–BEX 21303-7).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Data were analyzed by A.L. Carvalho, Z. Khan, and J.A. Califano.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

J. A. Califano is the Director of Research of the Milton J. Dance Head and Neck Endowment. The terms of this arrangement are being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Under a licensing agreement between Oncomethylome Sciences, SA and the Johns Hopkins University, D. Sidransky is entitled to a share of royalty received by the University upon sales of diagnostic products described in this article. D. Sidransky owns Oncomethylome Sciences, SA stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under University policy. D. Sidransky is a paid consultant to Oncomethylome Sciences, SA and is a paid member of the company’s Scientific Advisory Board. The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies is managing the terms of this agreement.

References

- 1.Palmisano WA, Divine KK, Saccomanno G, Gilliland FD, Baylin SB, Herman JG, et al. Predicting lung cancer by detecting aberrant promoter methylation in sputum. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5954–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belinsky SA, Liechty KC, Gentry FD, Wolf HJ, Rogers J, Vu K, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in sputum precedes lung cancer incidence in a high-risk cohort. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3338–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoque MO, Begum S, Topaloglu O, Jeronimo C, Mambo E, Westra WH, et al. Quantitative detection of promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in the tumor, urine, and serum DNA of patients with renal cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5511–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nunes DN, Kowalski LP, Simpson AJ. Detection of oral and oropharyngeal cancer by microsatellite analysis in mouth washes and lesion brushings. Oral Oncol. 2000;36:525–8. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosas SL, Koch W, da Costa Carvalho MG, Wu L, Califano J, Westra W, et al. Promoter hypermethylation patterns of p16, O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase, and death-associated protein kinase in tumors and saliva of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:939–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Naggar AK, Mao L, Staerkel G, Coombes MM, Tucker SL, Luna MA, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in saliva from patients with oral squamous carcinomas: implications in molecular diagnosis and screening. J Mol Diagn. 2001;3:164–70. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60668-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee A, Kim Y, Han K, Kang CS, Jeon HM, Shim SI. Detection of tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen, APC, and cyclin D2 in fine-needle aspiration fluid of breast. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1251–6. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-1251-DOTMIC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark SJ, Melki J. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer: which is the guilty party? Oncogene. 2002;21:5380–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha PK, Califano JA. Promoter methylation and inactivation of tumour-suppressor genes in oral squamous-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:77–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard PS, Wittwer CT. Real-time PCR technology for cancer diagnostics. ClinChem. 2002;48:1178–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, et al. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:E32. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.e32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeronimo C, Usadel H, Henrique R, Oliveira J, Lopes C, Nelson WG, et al. Quantitation of GSTP1 methylation in non-neoplastic prostatic tissue and organ-confined prostate adenocarcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1747–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho AL, Jeronimo C, Kim MM, Henrique R, Zhang Z, Hoque MO, et al. Evaluation of promoter hypermethylation detection in body fluids as a screening/diagnosis tool for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:97–107. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9821–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harden SV, Tokumaru Y, Westra WH, Goodman S, Ahrendt SA, Yang SC, et al. Gene promoter hypermethylation in tumors and lymph nodes of stage I lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1370–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao M, Rosenbaum E, Carvalho AL, Koch W, Jiang W, Sidransky D, et al. Feasibility of quantitative PCR-based saliva rinse screening of HPV for head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:605–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perneger TV. What is wrong with Bonferroni adjustments? BMJ. 1998;316:3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990;1:43–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho AL, Magrin J, Kowalski LP. Sites of recurrence in oral and oropharyngeal cancers according to the treatment approach. Oral Dis. 2003;9:112–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Esteller M, Wu L, Nawroz-Danish H, Yoo GH, Koch WM, et al. Gene promoter hypermethylation in tumors and serum of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:892–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Righini CA, de Fraipont F, Timsit JF, Faure C, Brambilla E, Reyt E, et al. Tumor-specific methylation in saliva: a promising biomarker for early detection of head and neck cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1179–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]