Abstract

Mycotic encephalitis caused severe ataxia and other neurologic deficits in a horse. The finding of a single, large focus of cerebral malacia, with histopathologic evidence of fungal elements, suggested infection was a result of direct transfer from the frontal sinuses, rather than hematogenous spread from the guttural pouch.

Résumé

Encéphalite mycotique, ostéomyélite des sinus et mycose de la poche gutturale chez un poulain arabe âgé de 3 ans. Une encéphalite mycotique a causé une ataxie grave et d’autres déficits neurologiques chez un cheval. La découverte d’un grand foyer unique de malacie cérébrale avec une preuve histopathologique d’éléments fongiques a suggéré que l’infection était un transfert direct des sinus frontaux, plutôt qu’une propagation hématogène provenant de la poche gutturale.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

A 3-year-old, male Arabian horse was presented to Edmonton Equine Veterinary Services in late spring with a history of acute, profuse nasal bleeding and severe ataxia of unknown duration. The horse had been turned out to pasture the previous fall with 7 other horses. The herd was being fed timothy hay from round bales, and heated water from an automatic water dispenser. One other horse in the herd displayed mild ataxia 2 wk after the presentation of this patient. The remaining 5 horses appeared normal.

Case description

Physical examination revealed normal temperature, pulse, and respiratory rate. The frontal bones had several hard, domed protrusions that were smooth, circular and measured between 8 mm and 2 cm in diameter, and were more prominent on the left than the right. An abbreviated neurologic assessment showed grade 4/5 neurologic deficits (1). The horse was severely ataxic on all 4 limbs and he preferred to lean his right side against a wall. Menace responses were bilaterally absent, but direct pupillary light reflexes (PLR) were present in both eyes. Tongue tone was reduced and moderate dysphagia was present. Despite his neurologic deficits, the horse was alert. He tended to be hyper-reactive to auditory and tactile stimuli.

A brief endoscopic examination of the upper airway revealed right laryngeal hemiplasia. The guttural pouches were not entered despite the history of nasal hemorrhage, as the level of ataxia displayed by the horse made a thorough endoscopic examination of the upper airway hazardous to both personnel and equipment. Radiographs of the frontal and maxillary sinuses showed a non-union fracture of the left frontal bone with bony callus proliferating around the fracture site. Descending from the callus toward the molar tooth roots was a peculiar, radio-opaque structure with multiple foci of lysis.

The left frontal sinus was trephined in order to surgically sample the mass seen on radiographs. The mass was firm and easily delineated from the surrounding structures. Biopsies were submitted for histopathology, and material collected was sent for bacterial and fungal cultures.

Blood drawn for a complete blood (cell) count (CBC) on initial examination showed a significant monocytosis at 9.6 × 109/L (normal: 0.0 to 0.46 × 109 cells/L). The packed cell volume was low at 0.26 L/L (normal: 0.32 to 0.52 L/L), but the remainder of the hemogram was normal. Biochemical analysis of the serum showed a hyperglycemia (9.1 mmol/L; normal: 2.6 to 6.1 mmol/L), hyperbilirubinemia (52 μmol/L; normal: 9 to 49 μmol/L), and an elevated creatine kinase (808 IU/L; normal: 30 to 357 IU/L). These findings were consistent with stress, recent hemorrhage, and muscle trauma. A severe deficiency in serum iron (3 μmol/L; normal: 17 to 37 μmol/L) combined with the monocytosis was consistent with a significant chronic inflammatory process. A repeat CBC 48 h following the initial examination and treatment showed a progression in the inflammatory response with a slight increase in the monocytosis (10.1 × 109/L) and a hyperfibrinogenemia (6.0 g/L; normal: 2.0 to 4.0 g/L).

Treatment was initiated with oral erythromycin (Apo-Erythro-S; Apotex Inc; Toronto, Ontario), 25 mg/kg body weight (BW), q12h, rifampin (Sanofi Aventis, Laval, Quebec), 5 mg/kg BW, q12h, and intravenous flunixin meglumine (Flunazine; Vétoquinol; Lavaltrie, Quebec), 1.1 mg/kg BW, q24h, while awaiting biopsy results. Clinical signs worsened despite treatment, so the horse was euthanized with an overdose of intravenous sodium pentobarbital (Euthanyl Forte; Bimeda-MTC; Cambridge, Ontario), 128 mg/kg BW. The head was submitted for necropsy.

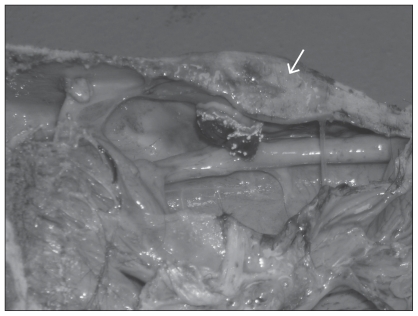

Gross postmortem examination was performed on the head and neck to the level of C4. The 3 swellings, originally noted on physical examination of the frontal bone, were so hard that they had to be sectioned with a band saw. Upon sectioning, foci of lysis and necrosis of the internal bone structure were evident. Internally in the right frontal sinus there was a round, nodular, fibrous proliferative mass growing from the internal surface of the right frontal bone ventrally into the right frontal sinus. This measured 1.5 cm in diameter at its base, and protruded approximately 1.5 cm into the sinus cavity. The mass was covered by a layer of inflammatory debris on which white fungal colonies were growing freely and were readily visible to the unaided eye (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mycotic osteomyelitis of the right frontal bone (arrow) with a blood-covered downward growth of proliferating fibrous tissue. Note proximity of the reaction to the cribriform plate. This is the probable route of infection of the brain.

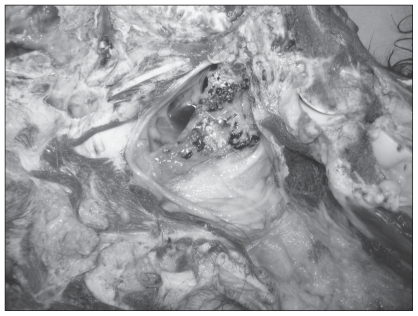

The left guttural pouch was grossly normal. The mucous membranes of the right guttural pouch were covered with a mixture of fibrin, blood, and necrotic debris. The mucosa over and the connective tissue around the stylohyoid bone were remarkably thickened, in places to a depth of 1.5 cm, with proliferating fibrous tissue, an inflammatory infiltrate, necrotic debris and colonies of fungi (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mucosa of the right guttural pouch over the stylohyoid bone showing necrotic and inflammatory debris, blood, and fungal colonies (white) on the surface. Note the remarkable thickening of the normally thin mucosa over the bone.

In the brain there was a 6 cm × 1 cm area of yellow discoloration and softening of the lateral right cerebral cortex, with general loss of grey matter. Even following formalin fixation, which normally significantly hardens brain tissue, the affected area was palpably softened. The neuropil in the anterior aspect of the lesion was disorganized and lacked a clear difference between grey and white matter.

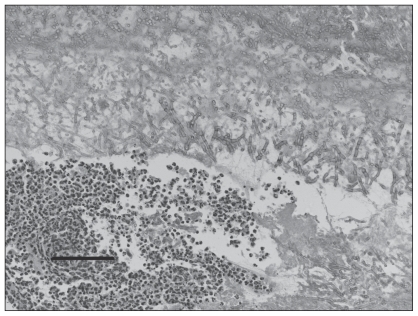

Histopathologic examination of the wall of the right guttural pouch over the stylohyoid bone revealed multiple layers of fibrous connective tissue of different densities. The whole mass was infiltrated by a mixed population of mononuclear inflammatory cells. Towards the surface there were blood, necrotic debris, macrophages, giant cells, and clusters of neutrophils, as well as tangled masses of fungal mycelia and sporangia (Figure 3). The fungi were typical of Aspergillus species, and the genus of the fungus was later verified by fungal culture results. Species was not identified. Sections of the nodular proliferation of the right frontal bone revealed a similar reaction to that over the stylohyoid bone with a layered mass of fibrous tissue covered by a smaller amount of inflammatory debris than in the guttural pouch, and distinct colonies of Aspergillus spp. growing on the surface. There was some proliferation of the underlying bone, but most of the mass was fibrous tissue. Sections of the brain from the most softened area revealed diffuse, mycotic encephalitis, with destruction of the neuropil and replacement with a disorganized mass of microglia, macrophages, giant cells, and fungal mycelia. There were large empty spaces in the cortex that were traversed by blood vessels.

Figure 3.

Material overlying the right stylohyoid bone. The mucosa has been lost and a mass of fibrin, tangled fungal mycelia and clusters of neutrophils are evident. Hematoxylin & eosin, 200×, bar =100 μm.

Discussion

Mycotic encephalitis is a rare cause of neurologic disease in the horse, and previously reported cases have implicated hematogenous spread from an infected guttural pouch as the mode of infection. As in previous reports, this case did have unilateral guttural pouch mycosis. Mycotic infection of the guttural pouch can have catastrophic sequelae, as infection often damages the major vessels and nerves that traverse the pouch. The most catastrophic of these sequelae include uncontrollable epistaxis, and aspiration pneumonia secondary to pharyngeal paralysis (2,3).

Guttural pouch mycosis is one of the more common diseases to affect the guttural pouch, with Aspergillus spp. being the most common causative agent (4,5). The fold of mucosa over the internal carotid artery (ICA) is a site of specific predilection for mycotic infection, possibly because of the higher local temperature, or the rhythmic pulsing of the artery (2). Cases in which mycotic infection has avoided the ICA and instead invaded the maxillary artery have also been reported, although this is far less common (6). This case is atypical in that the fungal colonies proliferated on the stylohyoid bone, but did not invade either the internal carotid or maxillary artery. It is unclear which vascular structure was responsible for the history of epistaxis; however, the degree of hemorrhage within the right pouch indicates that it was the source of the epistaxis. Inflammation of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves within the pouch were likely responsible for the horse’s dysphagia and right laryngeal hemiplasia.

The infection of multiple structures of the head in this case was unusual. Several cases of guttural pouch mycosis erosion into adjacent structures have been reported (7–12). Mycotic sinusitis has been reported in humans (13), but not in equids. Given the general infection of the brain, guttural pouch, and frontal sinus bones, it is likely that infection of the frontal sinus and guttural pouch with Aspergillus spores was simultaneous rather than successive. This implies that at some previous time there was aerosol exposure to large numbers of Aspergillus spores that colonized both the frontal sinuses and right guttural pouch. Spread of infection to the brain most likely occurred from the nasal cavity via the cribriform plate. Hematogenous spread from the guttural pouch seems unlikely in this case given the localization of infection to the right lateral lobe of the brain, and the lack of invasion of the right internal carotid artery or other vessels.

The severity of encephalomalacia in this case was outstanding and can certainly account for the level of ataxia. The structures of the eye, optic nerve, and optic tracts within the brain appeared normal on gross pathology. Given the presence of a PLR bilaterally, it is likely that blindness was central in origin in this case, resulting from the massive loss of neuropil.

The severity and combination of pathology associated with this case made treatment futile. Even if the mycosis had been localized to the guttural pouch and the bone of the frontal sinuses, treatment would have been difficult. Successful treatment of guttural pouch mycosis typically requires surgical occlusion of either the ICA, external carotid artery (ECA), or both (14). This can be accomplished by ligation, balloon tip catheter placement or transarterial coil embolization. Because neither the ICA nor the ECA branches was being invaded in this case, occlusion of those arteries is unlikely to have had a curative effect. A guttural pouch catheter could have been inserted to institute direct antifungal therapy; however, guttural pouch mycosis is often refractory to medical therapy, particularly when dysphagia is present (14,15).

This horse lived on pasture with several other horses. Infection likely involved inhalation of a high volume of Aspergillus spores from a round bale. Consistent with this suggestion is the manifestation of clinical signs in the early spring. Interestingly, a second horse in the same pasture also displayed neurologic signs shortly after the horse in this case study. Due to financial constraints, the owner opted to forego diagnostics and have her regular veterinarian euthanize this horse on the farm. A diagnosis was never determined, but the similarity in clinical signs makes one suspicious of a similar diagnosis.

This case is particularly interesting due to the combination and severity of pathology. Mycotic encephalitis is a rare sequela to guttural pouch mycosis and previous reports have indicated a hematogenous spread. In this case, the mycotic encephalitis seems to have been a sequela to a fungal sinusitis that was seeded at the same time as the unilateral guttural pouch mycosis. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Reed SM, Andrews F. Disorders of the neurologic system. In: Reed SM, Bayly WM, Sellon DC, editors. Equine Internal Medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders; 2004. pp. 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook WR. Observations on the aetiology of epistaxis and cranial nerve paralysis in the horse. The Vet Rec. 1966;78:396–406. doi: 10.1136/vr.78.12.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nation PN. Epistaxis of guttural pouch origin in horses: Pathology of three cases. Can Vet J. 1987;19:194–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lepage OM, Perron MF, Cadore JL. The mystery of fungal infection in the guttural pouches. Vet J. 2004;168:60–64. doi: 10.1016/S1090-0233(03)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig A, Gatineau S, Reynaud MC, et al. Fungal isolation and identication in 21 cases of guttural pouch mycosis in horses (1998–2002) Vet J. 2005;169:457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith KA, Barber SM. Guttural pouch hemorrhage associated with lesions of the maxillary artery in two horses. Can Vet J. 1984;25:239–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs KA, Fretz PB. Fistula between the guttural pouches and the dorsal pharyngeal recess as a sequel to guttural pouch mycosis in the horse. Can Vet J. 1982;23:117–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon PM, Rowlands AC. Atlanto-occipital joint infection associated with guttural pouch mycosis in a horse. Equine Vet. 1981;13:260–262. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1981.tb03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsmley JP. A case of atlanto-occipital arthropathy following guttural pouch mycosis in a horse. The use of radioisotope bone scanning as an aid to diagnosis. Equine Vet J. 1988;20:219–220. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1988.tb01504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin BG, O’Brien JL. Guttural pouch mycosis and mycotic encephalitis in a horse. Can Vet J. 1986;27:109–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner PC, Miller RA, Gallina AM, et al. Mycotic encephalitis associated with a guttural pouch mycosis. J Equine Med Surg. 1978;2:335–359. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatziolos BC, Albert TF. Ocular changes in a horse with gutturomycosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1975;167:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell RG, Chaplin AJ, Mackenzie WR. Emericella nidulans in a maxillary sinus fungal mass. J MedVet Mycol. 1987;25:339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greet TRC. Outcome of treatment in 35 cases of guttural pouch mycosis. Equine Vet J. 1987;19:483–487. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1987.tb02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis EW, Legendre AM. Successful treatment of guttural pouch mycosis with itraconazole and topical enilconazole in a horse. J Vet Internal Med. 1994;8:304–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]