Abstract

PURPOSE

To compare the prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) across Asian-American subgroups (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese) and non-Hispanic white (NHW) subjects in a mixed-payer, outpatient health care organization in California.

METHODS

Electronic health records from 2007 to 2010 were examined for 94,423 Asian and NHW patients. Age-adjusted prevalence rates of CHD, stroke, and PVD, defined by physician International Classification of Diseases, Version 9, codes, were directly standardized to the NHW population. Age-adjusted odds ratios were calculated by the use of logistic regression for each Asian subgroup, by sex, compared with NHWs.

RESULTS

The range of age-adjusted prevalence rates were: CHD (1.7%–5.2%), stroke (0.3%–1.8%), and PVD (0.9%–3.4%). The adjusted odds ratios of CHD were significantly higher for Filipino women (1.66; 95% confidence interval; 1.13–2.43) and men (1.47, 1.05–2.06) and Asian Indian men (1.77, 1.43–2.21), and significantly lower for Chinese women (0.72, 0.55–0.94) and men (0.78, 0.65–0.93), compared with NHWs. The odds of stroke were significantly greater for Filipino women (2.02, 1.22–3.34). The odds of PVD were generally lower for all Asian subgroups.

CONCLUSION

There is considerable heterogeneity across Asian subgroups for prevalent CHD, stroke, and PVD. Future research should disaggregate Asian subgroups and cardiovascular outcomes to inform targeted prevention and treatment efforts.

Keywords: Asian, Cardiovascular Diseases, Coronary Heart Disease, Peripheral Vascular Disease, Stroke

INTRODUCTION

Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in the United States, with a population of more than 14 million that is projected to reach nearly 34 million by 2050 (1), and more than one-third (4.7 of 14.1 million) of all Asian Americans live in California (2). The Asian-American population is racially and ethnically heterogeneous, with the six largest subgroups (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese) comprising approximately 90% of Asian Americans (3).

Much of our knowledge of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in Asian Americans, however, has been determined by studies in which the authors have either grouped Asian Americans together or examined one subgroup alone. National registries of CVD, such as the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction and the Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry, only report data for aggregated Asian Americans, masking possible heterogeneity among the subgroups (4, 5). In large-scale epidemiologic studies of CVD among Asian Americans, such as the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) (6) and the Honolulu Heart Program (7), authors have examined one Asian subgroup alone (Chinese and Japanese, respectively), precluding comparisons across subgroups. Research findings determined by the aggregated Asian-American group or one subgroup alone are often presumed to be applicable for all other subgroups.

The only nationally representative data for CVD among Asian Americans comes from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). According to the 2008 NHIS, national prevalence rates for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke among adults 18 years of age and older are 2.9% and 1.8%, respectively, for aggregated Asian Americans, compared with 6.5% and 2.7% for Non-Hispanic white (NHW) subjects (8).

Barnes et al. (9) used NHIS data from 2004 to 2006 to determine national estimates of heart disease and stroke among Asian subgroups. However, because of small sample sizes in some Asian subgroups, the NHIS data do not produce statistically stable estimates for some subgroup-level analyses of heart disease and stroke (9). In addition, NHIS is based on self-reported data and does not include clinical records, which may lead to underestimated prevalence rates of CVD (10). Currently there are no publicly available data sources that are large enough to provide prevalence rates for CHD, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) for Asian-American subgroups (9, 11).

Although few studies have examined Asian-American subgroups individually, the limited data available suggest variation in the prevalence of CHD, stroke, and PVD across Asian subgroups. Various small studies in which the authors have examined a few specific subgroups have shown greater rates of CHD in Asian Indians (12, 13) and Filipinos (12), greater rates of hemorrhagic stroke among Chinese (14), and lower rates of CHD and PVD among Chinese (12, 15), compared withNHWsubjects. These studies, however, have generally focused on one or two subgroups alone. In addition, differences in methods and population selection make it difficult to make comparisons of subgroups across studies. The objective of this analysis was to use a single data source to determine and compare the relative prevalence of CHD, stroke, and PVD across Asian-American subgroups (Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese) and NHW subjects from a large mixed-payer, outpatient health care organization in California.

METHODS

Setting

A mixed-payer, outpatient health care organization serves approximately 400,000 active patients, in the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. This Northern California health care organization is unique among large clinical data resources because more than 30% of the overall patient population self-identifies as Asian-American. The demographic characteristics of the patients are similar to that of residents in the surrounding service area (Alameda, San Mateo, and Santa Clara counties) with respect to race/ethnicity and age distribution, but the patient population has a slightly greater proportion of women, NHWs, and Asians, and fewer Blacks/African-Americans and Hispanics. Among Asian-American patients, the representation of Korean and Vietnamese subjects in the patient population is disproportionately lower when compared with the service area. The patient population is insured (58% preferred provider organization, 23% health maintenance organization, 16% Medicare, 2% self-payer, and 1% Medicaid), and thus underrepresents the medically underserved. Accordingly, access to care is unlikely to confound subgroup comparisons.

Study Design

A 3-year, cross-sectional sample from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2009 of active patient electronic health records was studied. Active patients aged 35 years and older with a self-identified (52%) (16) or name-inferred (48%) (17) race/ethnicity of: Asian Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or NHW were included in these analyses. Mixed-race/ethnicity patients were excluded from analysis. Name-inferred race/ethnicity was determined by matching patient name to published Asian surname and given name lists (name lists are available from Diane Lauderdale at lauderdale@uchicago.edu) through an algorithm that was developed and previously published by the authors (17). The derivation of the surname lists, by the use of files at the Social Security Administration, has been previously described (18), and the name lists have been validated in this population (17) with high positive predictive values as high as 0.92 for identifying specific Asian subgroups. Clinical characteristics, such as blood pressure and body mass index, were nearly identical for Asian subgroup comparisons regardless of whether subgroup was assigned based on self-identified ethnicity or name-inferred ethnicity (17).

Results for Asian subgroups are presented separately and as a single aggregated group, both compared with NHW subjects. All data sets were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (19) deidentified. To meet Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act deidentification requirements, all ages older than 90 years (as of 2012) were grouped into a single category. The analyses were repeated on the subset with self-identified race/ethnicity only, and the main findings were similar to the entire group (results not shown). No patients were contacted for the study, which received approval from the organization’s Institutional Review Board on August 14, 2008.

Clinical Definitions

Physician recorded International Classification of Diseases, Version 9 codes were used to identify CHD (410–414), stroke (430–434), and PVD (415, 440.2, 440.3, 443.9, 451, 453). Ischemic (433–434) and hemorrhagic (430–432) subclasses of stroke were also examined. Transient cerebral ischemia (435), other, and ill-defined (436–437) and late effects (438) of cerebrovascular disease were excluded from the analysis to prevent possible contamination by other neurological symptoms. PVD subclasses included peripheral arterial disease (440.2, 440.3, 443.9) and venous disease (415, 451, 453). Prevalent cases were defined as patients who ever had a diagnosis code for CHD, stroke, or PVD.

Statistical Methods

First, the age and sex distributions across groups were compared by the use of χ2 tests. Age-adjusted prevalence rates of CHD, stroke, and PVD by race/ethnicity and sex were calculated by the use of direct standardization to the age distribution of NHWs. Broad age categories (35–54, 55–64, 65–75, 75+ years) were used to achieve stable stratum-specific rates for direct standardization. Then, logistic regression was used to estimate age-adjusted odds ratios for each racial/ethnic subgroup. Logistic regression models were fit separately for men and women and with CHD, stroke or PVD as separate outcomes. Each model included indicator variables for racial/ethnic subgroups and 5-year age categories. Non-Hispanic White was the referent group in all models.

In sensitivity analyses, the classification of PVD by subtypes mentioned earlier were considered. For the arterial and venous subclasses of PVD, event counts were too few to examine groups separately by sex and race/ethnicity; therefore Asian Americans were considered as a single category and compared to NHWs. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals are reported when appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 94,423 eligible records (21,722 Asians and 72,701 NHWs) were identified and the patient characteristics are described in Table 1. Overall Asians were significantly younger than NHWs, and median age in 2007 ranged from 41 years in Asian Indians to 49 years in Japanese, and 50 years in NHWs. Table 1 also shows the ageadjusted prevalence rates of CHD, stroke (overall, and by ischemic and hemorrhagic subtypes), and PVD (overall, and by arterial and venous disease), which were 3.6%, 1.2%, 1.4% respectively in the aggregated Asian group, compared with 3.9%, 1.2%, 3.4% in NHWs.

TABLE 1.

Age and sex distribution of Asian and non-Hispanic white (NHW) active patients, from 2007 to 2009, with directly standardized prevalence rates of coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and peripheral vascular disease (PVD)

| NHW | Asian (all) | Asian Indian | Chinese | Filipino | Japanese | Korean | Vietnamese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N) | 72,701 | 21,722 | 5,154 | 10,659 | 2,261 | 1,598 | 924 | 1,126 |

| Women (%) | 56% | 57% | 46%* | 59%* | 65%* | 64%* | 63%* | 59% |

| Age (yr) (N, %)† | ||||||||

| 35–54 | 44,250 (61) | 16,612 (76) | 4,325 (84) | 7,941 (75) | 1,631 (72) | 1,033 (65) | 758 (82) | 924 (82) |

| 55–65 | 14,412 (20) | 2,610 (12) | 443 (9) | 1,339 (13) | 394 (17) | 251 (16) | 75 (8) | 108 (10) |

| 65–75 | 7,192 (10) | 1,474 (7) | 271 (5) | 797 (7) | 155 (7) | 132 (8) | 68 (7) | 51 (5) |

| 75+ | 6,847 (9) | 1,026 (5) | 115 (2) | 582 (5) | 81 (4) | 182 (11) | 23 (2) | 43 (4) |

| CHD | ||||||||

| Counts | 2,805 | 508 | 134 | 221 | 72 | 44 | 9 | 28 |

| Prev. rate | 3.9% | 3.6% | 5.2%* | 3.0% | 5.1% | 2.9% | 1.7% | 5.2% |

| 95% CI | (3.7–4.0) | (3.3–3.9) | (4.3–6.1) | (2.6–3.3) | (4.0–6.3) | (2.1–3.8) | (0.4–3.0) | (3.4–7.0) |

| Stroke | ||||||||

| Overall | ||||||||

| Counts | 846 | 160 | 26 | 77 | 25 | 20 | 3 | 9 |

| Prev. rate | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 1.2% | 0.3%* | 1.7% |

| 95% CI | (1.1–1.2) | (1.0–1.4) | (0.5–1.5) | (0.8–1.3) | (1.0–2.6) | (0.7–1.8) | (0.0–0.8) | (0.6–2.8) |

| Hemorrhagic | ||||||||

| Counts | 165 | 41 | 6 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Prev. rate | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.7% |

| 95% CI | (0.2–0.3) | (0.2–0.4) | (0.0–0.2) | (0.1–0.3) | (0.0–0.7) | (0.1–0.7) | (0.0–0.8) | (0.0–1.5) |

| Ischemic | ||||||||

| Counts | 698 | 122 | 21 | 61 | 20 | 14 | 0 | 6 |

| Prev. rate | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 0%* | 1.1% |

| 95% CI | (0.9–1.0) | (0.8–1.1) | (0.5–1.4) | (0.6–1.1) | (0.8–2.2) | (0.4–1.3) | (0.0–0.0) | (0.2–2.0) |

| PVD | ||||||||

| Overall | ||||||||

| Counts | 2,502 | 195 | 52 | 92 | 24 | 17 | 5 | 5 |

| Prev. rate | 3.4% | 1.4%* | 2.0%* | 1.3%* | 1.7%* | 1.0%* | 1.1%* | 0.9%* |

| 95% CI | (3.3–3.6) | (1.2–1.6) | (1.4–2.7) | (1.0–1.5) | (1.0–2.4) | (0.5–1.5) | (0.0–2.3) | (0.1–1.7) |

| Arterial disease | ||||||||

| Counts | 1,407 | 114 | 26 | 58 | 16 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| Prev. rate | 1.9% | 0.9% | 1.4% | 0.9%* | 1.3% | 0.5%* | 0.8% | 0.5%* |

| 95% CI | (1.8–2.0) | (0.8–1.1) | (0.8–2.1) | (0.7–1.1) | (0.6–1.9) | (0.2–0.9) | (0.0–1.9) | (0.0–1.1) |

| Venous disease | ||||||||

| Counts | 1,203 | 87 | 27 | 35 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| Prev. rate | 1.7% | 0.5%* | 0.6%* | 0.4%* | 0.6%* | 0.5%* | 0.3%* | 0.4%* |

| 95% CI | (1.6–1.7) | (0.4–0.6) | (0.3–0.9) | (0.3–0.6) | (0.2–1.0) | (0.2–0.8) | (0.0–0.7) | (0.0–0.9) |

Rates were standardized to the age distribution of the NHW population.

Significantly different from NHW prevalence rate at p < 0.05.

Asian (all) and all subgroups were statistically significantly different from NHW at p < 0.05 by χ2 tests.

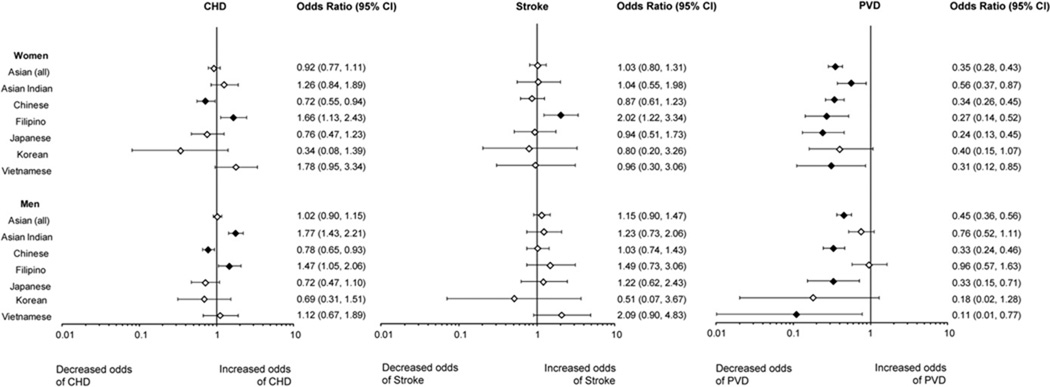

Age-adjusted odds ratios for CHD, stroke, and PVD are presented in Figure 1. Odds ratios (ORs) of CHD for Asian women as a single category were 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77–1.11) but ranged in the subgroups from 0.34 (0.08–1.39) for Koreans to 1.78 (0.95–3.34) for Vietnamese. Odds of CHD were significantly greater for Filipino women (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.13–2.43) and significantly lower for Chinese women (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.55–0.94). The odds ratios of CHD for Asian men as a single category was 1.02 (0.90–1.15) and ranged in the subgroups from 0.69 (0.31–1.51) for Koreans to 1.77 (1.43–2.21) for Asian Indians. Compared with NHWs, Asian Indian (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.43–2.21) and Filipino (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.05–2.06) men had significantly increased odds, whereas Chinese men (OR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65–0.93) had lower odds of CHD.

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted OR of CHD, stroke, and PVD by gender and Asian subgroup compared with NHWs. The diamond indicates the point estimate and the bar represents the 95% CI. Filled diamonds indicate statistical significance compared with NHWs at p < 0.05.

The ORs for stroke, compared with NHWs, were 1.03 (95% CI, 0.80–1.31) for all Asian women and ranged from 0.80 (0.20–1.73) for Korean women to 2.02 (1.22–3.34) for Filipino women. Filipino women had significantly greater odds of stroke (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.22–3.34). As a single category, Asian men had an OR for stroke of 1.15 (0.90–1.47), ranging from 0.51 (0.07–3.67) for Korean men to 2.09 (0.90–4.83) for Vietnamese men. Ischemic stroke accounted for the majority (81.5%) of all strokes. The odds of ischemic stroke were significantly greater for Filipino women (2.00, 1.15–3.47), and the odds of hemorrhagic stroke were significantly greater for Korean women (4.23, 1.02–17.56) and Vietnamese men (4.28, 1.32–13.83). There were no ischemic strokes to report for Korean men and women.

The odds of PVD were significantly lower for men and women for Asians as a single category and in nearly all Asian subgroups, compared to NHWs. ORs for PVD in Asian women were 0.35 (95% CI, 0.28–0.43) and ranged in the subgroups from 0.24 (0.13–0.45) for Japanese women to 0.56 (0.36–0.87) for Asian Indian women. For men, ORs for PVD were 0.45 (0.36–0.56) in Asians and ranged in the subgroups from 0.11 (0.01–0.77) for Vietnamese to 0.96 (0.57–1.63) for Filipinos.

In sensitivity analyses, subclasses of PVD, arterial and venous disease, were separated and further examined. Similar to the primary analyses showing significantly lower odds of PVD for Asians as a single group, Asians also had lower odds of arterial disease (women: 0.41; 0.31–0.55 and 0.60; 0.45–0.79) and venous disease (women: 0.31; 0.24–0.42, men: 0.32; 0.23–0.46). Age-adjusted prevalence rates are presented for each Asian subgroup in Table 1. However, confidence intervals are wide for some groups because of the small numbers of events. For all Asian subgroups, age-adjusted rates of peripheral venous disease were lower, compared to NHWs. Age-adjusted rates of peripheral arterial disease were also lower for most Asian subgroups.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to obtain estimates based on clinical data of CHD, stroke, and PVD for the six largest Asian subpopulations (Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese) in the United States. These findings support previous research that has suggested considerable heterogeneity in Asian-American subgroups with regard to CHD, stroke, and PVD prevalence. Our findings indicate that Filipinos and Asian Indians generally diverge from the other Asian subgroups, with both groups showing elevated risk for CHD and Filipino women elevated risk for overall stroke. When subclasses of stroke were examined, significantly greater risk of ischemic stroke was found for Filipino women, and greater risk of hemorrhagic stroke was found for Vietnamese men and Korean women compared with NHWs. Significantly lower risk for CHD was found for Chinese men and women compared with NHWs. Because some of the subgroups have greater rates than NHWs and some lower, the ORs comparing the aggregate Asian group to NHWs for CHD and stroke are close to one and not statistically significant. In contrast, odds of PVD were generally lower among all Asian subgroups and the aggregate Asian group compared with NHWs.

The majority of studies in which the authors examined CVD in Asian Americans have focused on one Asian subgroup alone. The Ni-Hon-San study, a multisite study that included the Honolulu Heart Study, has tracked CVD in Japanese men since 1965 and demonstrated greater rates of CHD and lower rates of stroke for 16,580 Japanese Americans compared with 9,329 native Japanese (20, 21). The MESA study included 797 Chinese Americans and demonstrated lower congestive heart failure incidence and PVD prevalence rates for this subgroup compared with white subjects (15, 22). With only one subgroup in each of these studies, it is difficult to compare findings across Asian subgroups.

Klatsky and Tekawa used hospital record data collected approximately 30 years ago (1978–1985) from California to examine several Asian-American subgroups, including Chinese, Filipinos, Japanese, and Asian Indians. Although the Asian-American population has changed dramatically since, Klatsky and Tekawa similarly found that Asian Indian men and Filipino women were at greater risk whereas Chinese were at lower risk of hospitalization for CHD (12). Additional studies that used the same database found lower risk of PVD for Chinese Americans (12), Filipino Americans (12), and aggregated Asians (12, 23) compared with NHWs. The odds of CHD, stroke, and PVD among the Asian subgroups in our study population were generally similar to those reported by Klatsky and Tekawa. The studies by Klatsky and Tekawa were limited to hospitalization data, which would fail to capture patients that do not seek immediate medical care or receive care only in the outpatient setting. Our data source provides more recent data (2007–2009), two additional subgroups, and better captures patients ever diagnosed with CHD, stroke, and PVD. Nonetheless the consistency of our findings suggests the contrasts we found are not unique to this study population.

The only nationally representative data for CVD in Asian Americans is the NHIS, which is limited by self report and small sample sizes in the Asian subgroups. Our study sample is not national, and therefore our point estimates are not generalizable. However, relative differences in prevalence rates between the Asian subgroups are likely to be similar across the country, and thus help to identify highrisk groups. Our rates of CHD for NHWs and Asian Americans were generally lower than those reported by NHIS. NHIS did not report stroke rates for some of the subgroups. Although our rates of stroke were lower for NHWs and Chinese, compared with those of NHIS, the decrease was similar for both groups. Differences between our prevalence rates and those reported by NHIS may be due to differences in measurement (self-report versus health records) or may be to the result of real differences between our study population and the general U.S. population, reflecting geography, education, economic status or access to care.

Differences in traditional CVD risk factors between Asian-American subgroups may contribute to the observed differences in our CVD prevalence rates. Filipinos and Asian Indians have been shown to have greater prevalence rates of some traditional risk factors for CHD (24). Higher prevalence rates have been reported for type 2 diabetes among Filipinos (25, 26), and for type 2 diabetes (27–29) and physical inactivity (24) among Asian Indians compared with NHWs. The biggest risk factor for stroke is hypertension, which is a factor in nearly 70% of all strokes (30). Greater rates of hypertension have been reported for Filipinos compared to NHWs and other Asian-American subgroups (9, 24). Few investigators have examined PVD prevalence and risk factors among Asian Americans. Authors of the MESA study found that after adjusting for traditional (age, smoking, diabetes, body mass index, hypertension, and dyslipidemia) and novel risk factors, the OR for peripheral arterial disease was significantly lower for Chinese subjects, suggesting that intrinsic or unrecognized factors associated with race/ethnicity may account for this reduced risk (15). It has been hypothesized that genetic factors, particularly those involving clotting, may play a role in the reduced risk of PVD in Asian subjects (15, 23). We found that most Asian-American subgroups had lower prevalence of arterial and venous disease, compared to NHWs.

Limitations of this study include a single geographic area, with somewhat limited sample size in the smaller Asian subgroups (ie, Korean and Vietnamese populations). Although the Ni-Hon-San study demonstrates the importance of separating U.S-born from foreign-born, we were unable to identify migration status in our patient population. However, only 3% of our patients are limited English-proficient speakers, which may indicate a high level of acculturation among the Asian patient population. The small number of cases of CHD, stroke, and PVD, limit our ability to find significant differences for those smaller groups despite suggestive point estimates. CVD prevalence definitions were based on outpatient visits only. Although this may lead to underestimation of CVD prevalence, it is likely in this group of insured patients that any hospitalizations are followed by a follow-up outpatient visit with one of our providers. While, the exclusion of transient cerebral ischemia and other/ill-defined and late effects of cerebrovascular disease may underestimate actual cases of stroke, the specificity of overall stroke, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke is improved. The authors of previous studies have validated administrative data in identifying diagnoses of CHD and stroke and have shown them to be particularly useful in making high-level comparisons (31). The relative homogeneity in economic status in this clinical population (all insured, with access to health care) improves the internal validity of our comparisons.

In conclusion, our findings show marked heterogeneity in CVD prevalence among Asian-American subgroups, which is obscured when Asian subgroups are aggregated. Filipinos and Asian Indians appear to be at greater risk for CHD, and Filipino women at greater risk for stroke compared with NHWs and other Asian subgroups. Targeted prevention and treatment efforts may be especially needed for Filipinos and Asian Indians. Data on CVD risk factors and outcomes in Vietnamese and Korean American subpopulations are lacking and may underestimate risk in these subgroups. More research, particularly with a nationally representative population-based sample, needs to investigate CVD risk factors and outcomes separately among Asian subgroups to better understand variation in these disease patterns. The American Heart Association recently issued a scientific advisory (32) recommending changes in data collection—such as disaggregation of Asian Americans in the myocardial infarction (4) and stroke (5) registries, development of better standard measurements of diet and acculturation, and new research studies to improve health disparities among Asian Americans. These critical data are needed to better inform preventive and treatment interventions for CVD among Asian Americans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beinan Zhao for her contribution in validating the analytic data sets.

The effort for this manuscript was funded in part by the Asian American Heart Study, a study funded by the American Heart Association (0885049N).

Selected Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- MESA

Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- NHW

non-Hispanic white

- PVD

peripheral vascular disease

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

REFERENCES

- 1.Population Division U.S. Census Bureau. Table 17. Projections of the Asian Alone Population by Age and Sex for the United States: 2010 to 2050 (NO-2008-2T17) 2008 Aug 14;

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed May 3, 2010];State and Country QuickFacts. 2008 Available at: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html.

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. [Accessed May 5, 2011];Table C02006. Asian Alone by Selected Groups. 2006–2008 Available at: http://www.socialexplorer.com/pub/reportdata/metabrowser.aspx?survey=ACS2009&ds=American+Community+Survey+2009&table=C02006&header=True.

- 4.Canto JG, Taylor HA, Jr, Rogers WJ, Sanderson B, Hilbe J, Barron HV. Presenting characteristics, treatment patterns, and clinical outcomes of non-black minorities in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:1013–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George MG, Tong X, McGruder H, Yoon P, Rosamond W, Winquist A, et al. Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Surveillance—four states, 2005–2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trombold JC, Moellering RC, Jr, Kagan A. Epidemiological aspects of coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease: The Honolulu Heart Program. Hawaii Med J. 1966;25:231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat. 2009;10:1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006. Adv Data. 2008:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayan KM, Aviles-Santa L, Oza-Frank R, Pandey M, Curb JD, McNeely M, et al. Report of a National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute Workshop: heterogeneity in cardiometabolic risk in Asian Americans in the U.S. Opportunities for research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klatsky AL, Tekawa I. Health problems and hospitalizations among Asian-American ethnic groups. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:753–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klatsky AL, Tekawa I, Armstrong MA, Sidney S. The risk of hospitalization for ischemic heart disease among Asian Americans in northern California. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1672–1675. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang J, Foo SH, Jeng JS, Yip PK, Alderman MH. Clinical characteristics of stroke among Chinese in New York City. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allison MA, Criqui MH, McClelland RL, Scott JM, McDermott MM, Liu K, et al. The effect of novel cardiovascular risk factors on the ethnic-specific odds for peripheral arterial disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1190–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palaniappan LP, Wong EC, Shin JJ, Moreno MR, Otero-Sabogal R. Collecting patient race/ethnicity and primary language data in ambulatory care settings: A case study in methodology. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:1750–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong EC, Palaniappan LP, Lauderdale DS. Using name lists to infer Asian racial/ethnic subgroups in the healthcare setting. Med Care. 2010;48:540–546. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d559e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauderdale D, Kestenbaum B. Asian American ethnic identification by surname. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2000;19:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Repositories, Databases, and the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marmot MG, Syme SL, Kagan A, Kato H, Cohen JB, Belsky J. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: prevalence of coronary and hypertensive heart disease and associated risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1975;102:514–525. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagan A, Popper J, Rhoads GG, et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii, and California: Prevalence of stroke. In: Scheinberg P, editor. Cerebrovascular Diseases; No. Tenth Princeton Conference. New York: Raven Press; 1976. pp. 267–277. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, Liu K, Burke GL, et al. Differences in the incidence of congestive heart failure by ethnicity: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2138–2145. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA, Poggi J. Risk of pulmonary embolism and/or deep venous thrombosis in Asian-Americans. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1334–1337. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye J, Rust G, Baltrus P, Daniels E. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans: Results from a National Health Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanchoco CC, Cruz AJ, Duante CA, Litonjua AD. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Filipino adults aged 20 years and over. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araneta MR, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in Filipina-American women: a high-risk nonobese population. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:494–499. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enas EA, Mohan V, Deepa M, Farooq S, Pazhoor S, Chennikkara H. The metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia among Asian Indians: A population with high rates of diabetes and premature coronary artery disease. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.07392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oza-Frank R, Ali MK, Vaccarino V, Narayan KM. Asian Americans: Diabetes prevalence across U.S. and World Health Organization weight classifications. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1644–1646. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanaya AM, Wassel CL, Mathur D, Stewart A, Herrington D, Budoff MJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes in South asian indians in the United States: Findings from the metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis in South asians living in america study and the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:157–164. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronner LL, Kanter DS, Manson JE. Primary prevention of stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1392–1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511233332106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43:480–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palaniappan LP, Araneta MR, Assimes TL, Barrett-Connor EL, Carnethon MR, Criqui MH, et al. Call to action: Cardiovascular disease in Asian Americans. A science advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:1242–1252. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f22af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]