Abstract

Purpose

Radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation technology with its treatment protocols has shown efficacy in various psychiatric disorders. The aim of this work was to highlight the mechanisms by which these positive effects are achieved. The current study was conducted to determine whether a single 500-millisecond radioelectric asymmetric conveyor (REAC) brain stimulation pulse (BSP), applied to the ear, can effect a modification of brain activity that is detectable using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Methods

Ten healthy volunteers, six females and four males, underwent fMRI during a simple finger-tapping motor task before and after receiving a single 500-millisecond REAC-BSP.

Results

The fMRI results indicate that the average variation in task-induced encephalic activation patterns is lower in subjects following the single REAC pulse.

Conclusion

The current report demonstrates that a single REAC-BSP is sufficient to modulate brain activity in awake subjects, able to be measured using fMRI. These initial results open new perspectives into the understanding of the effects of weak and brief radio pulses upon brain activity, and provide the basis for further indepth studies using REAC-BSP and fMRI.

Keywords: fMRI, brain stimulation, brain modulation, REAC, neuropsychiatric treatments

Introduction

Radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation technology with its treatment protocols has shown efficacy in various psychiatric disorders.1–10 The aim of this work was to highlight the mechanisms by which these positive effects are achieved. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is used to measure the hemodynamic response (changes in blood flow and blood oxygenation) that results from neural activity in the brain.11–13 fMRI images have the advantage of good spatial resolution, about 2–3 mm.14 However, as the hemodynamic response typically peaks after 4–5 seconds,15,16 this method suffers from a low temporal resolution.17 Images are usually separated by 1–4 seconds, and the stimuli or the cognitive and motor tasks are carried out during the fMRI session. It has previously been observed that the changes in psychological1,3–10 and motor behavior activity18–20 resulting from radioelectric asymmetric conveyor (REAC) brain stimulation pulse (BSP) stimulation are relatively long lasting, the persistence of effects has been observed for a few years. Although the duration of the REAC stimulus is brief (500 milliseconds), it was hypothesized that changes in brain activity following stimulation would be observable using fMRI, despite the low temporal resolution of this imaging modality.

Methods

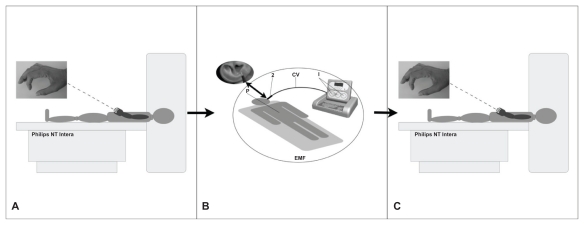

This preliminary study used unpaid right-handed healthy volunteers, in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Each subject gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Ten subjects were examined (six females, four males, aged 30–48 years, mean age 39 years), who underwent brain fMRI examination before and after a 500-millisecond REAC-BSP. Prior to fMRI examination, all subjects were informed about how to properly perform the finger-tapping motor task (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Protocol sequence.

Note: Philips NT Intera = NT Intera 1.5T MRI scanner (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands).

Abbreviations: EMF, electromagnetic field; CV, cable with probe.

fMRI examination

An NT Intera 1.5T MRI scanner (Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) was used to perform fMRI to evaluate the cerebral areas involved during a simple motor task (finger tapping)21 (Figure 1A) before and immediately after a 500-millisecond REAC-BSP. The area of interest was visualized using a survey protocol with images obtained along the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, on which a volumetric T1-weighted gradient echo sequence (T1 three-dimensional turbo field echo, repetition time = 13, echo time = 3, flip angle = 30°) and an fMRI sequence (T2 echo planar imaging-fast field echo, repetition time = 3000, echo time = 50, flip angle = 90°) were placed. Before administering REAC-BSP, the subjects were placed in a supine position and asked to perform a 30-second task that consisted of a self-paced right fingers to right thumb opposition movement task, alternating with equal periods of rest. Subjects performed 96 dynamic sequences during fMRI acquisition, which were divided into blocks of ten (30 seconds each) with the elimination of the first six sequences during rest. As a control, this sequence was repeated after an hour for each subject. Following the administration of the REAC-BSP, subjects were brought back to the magnet room to repeat the fMRI examination (Figure 1). This fMRI examination was also repeated after an hour for each subject. fMRI data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 2 (SPM2; The Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, London, UK) software package,22 using the familywise error rate correction routine23,24 that automatically sets the correct value of P = 0.05 at the voxel (a Volumetric Picture Element representing a value on a regular grid in three dimensional space) level.

REAC

The REAC25,26 is an innovative technology for biostimulation and/or bioenhancement techniques that uses weak radio frequencies to modulate brain activity. The model used in this study (Convogliatore di Radianza Modulante – CRM®; ASMED, Florence, Italy) is specific for noninvasive brain stimulation techniques.

REAC treatment has proved its efficacy in ameliorating several stress-related disorders,1,6–9 depression,5,9,10 anxiety,5,9 bipolar disorders,4 and also in some forms of dementias3 and impaired motor control.18,20 The REAC procedure is painless, and no adverse effects from its use have been reported. The REAC pulse used in the current study consisted of a single 500-millisecond radiofrequency burst at 10.5 GHz. At a distance of 150 cm from the emitter, a specific absorption rate of 7 μW/kg was obtained (and the density of radioelectric current flowing to the subject during the single radiofrequency burst was J = 7 μA/cm2. The electromagnetic field surrounding the device was approximately 20 μW/m2. The REAC pulse was applied by touching the tip of the metallic REAC probe to a specific area of the ear located at the top of the lower third of the scapha of the ear pavilion, according to the Neuro Postural Optimization protocol.7,9 With these parameters, the radioelectric pulses emitted by the REAC were much weaker than those from a mobile phone. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission has set a special absorption rate limit of 1.6 W/kg, averaged over a volume of 1 g of tissue, for the head. In Europe, the limit is 2 W/kg, averaged over a volume of 10 g of tissue. The World Health Organization has classified mobile phone radiation on the International Agency for Research on Cancer scale into Group 2B – possibly carcinogenic.

Results

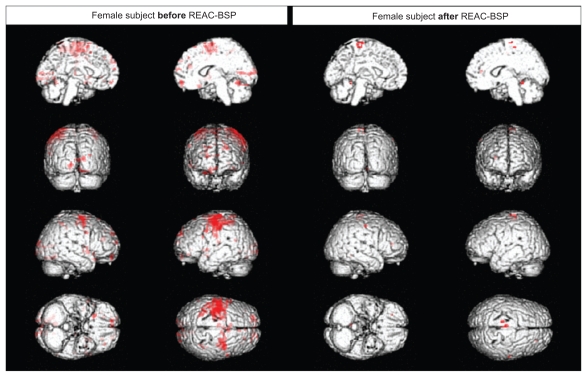

Following the REAC-BSP, a significant reduction in the amplitude of motor task-induced cortical area activation, and a reduced statistical significance (Z value) of the areas that remain activated, was observed in all subjects. As shown in Figure 2, images taken prior to the REAC-BSP in a representative female subject show large clusters of activation that include the premotor cortex contralateral to the limb used in the motor task (Figure 1A), the adjacent primary motor area, and the somatosensory cortex. Clear activation may also be observed in the ipsilateral premotor cortex, the bilateral visual cortex, the prefrontal cortex, and the superior cerebellar cortex ipsilateral to the limb used in the task. In control, following the REAC-BSP, the same task resulted in statistically significant activation only in the contralateral primary motor area and the dorsolateral prefrontal and superior cerebellar regions ipsilateral to the involved limb.

Figure 2.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging of a female subject.

Abbreviation: REAC-BSP, radioelectric asymmetric conveyor brain stimulation pulse.

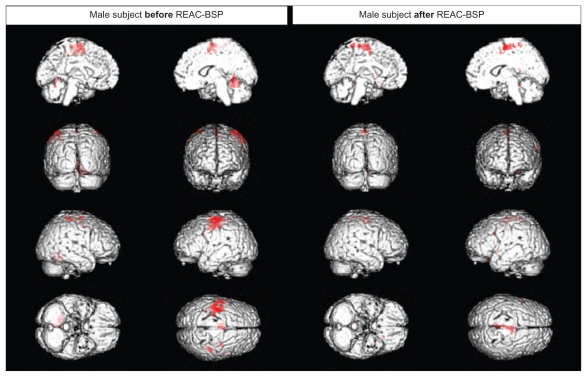

A similar phenomenon may be observed in a representative male subject (Figure 3). The effects of the REAC-BSP were observed as a significantly reduced signal amplitude following the motor task (Figure 1A) in the ipsilateral superior cerebellar, premotor, and primary motor cortex, compared to that observed prior to the REAC stimulation. In the fMRI session following the REAC-BSP, the disappearance of the larger clusters of activation that were present during the motor task (Figure 1A) prior to the REAC-BSP was observed, with activity persisting a small area of the medial premotor and motor cortex.

Figure 3.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging of a male subject.

Abbreviation: REAC-BSP, radioelectric asymmetric conveyor brain stimulation pulse.

Discussion

Based on available data, the efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), another technique of brain stimulation, is not comparable with other therapeutic strategies such as REAC. REAC has shown great stability of results, as demonstrated in a study on bipolar disorder with a follow-up period of about 4 years,4 whereas TMS has been shown to be efficient in the same psychiatric disorder only in the short-term. Also, in over 10 years of observation by the authors, many patients affected with recurrent depression achieved complete stabilization. However, some patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, which was sometimes treated with REAC, significantly worsened with TMS after an initial improvement. More than 16 cases of TMS-related seizure associated with single-pulse and repetitive TMS have been reported in the literature;31 other risks include fainting, syncope, pains, headache, minor cognitive changes, and psychiatric symptoms. Up until now, there have not been any noted negative side effects of REAC. Occasionally, a slight sense of vertigo has been reported when getting up from the examination table after REAC, but this feeling cannot be attributed to the treatment with any certainty.

In the current study, an event-related approach was used and it was demonstrated that the modulation of brain activity induced by a single, brief REAC pulse can clearly be measured using fMRI, allowing for further indepth study of brain activity modulation in human subjects. In all the subjects examined, a significant reduction in the amplitude and area of the cortical activation induced by a simple motor task (Figure 1A) was observed. This modulation was evident as a reduction in the Z significance value between the area of activation before and during the motor task. These findings might be explained by the occurrence of remodeling, which would involve not only a decrease of activation, but also a positive adjustment in the mapping of the areas involved in the execution of motor tasks. These findings suggest that the REAC pulse modulates activity only in those regions that are acutely necessary to the completion of the requested task, with the exclusion or inhibition of secondary circuits involved in somatosensory processing, motion planning, or executive feedback. The significant reduction in the amplitude of motor task-induced cortical area activation after REAC-BSP substantially means that to perform the same task the subject “uses” less brain areas and, in this view, it isn’t important if this phenomenon is related to primary areas, associative areas, or both. Given the magnitude of the changes observed in all brain activity, it is thought that, as with other brain stimulation techniques,28–31 the REAC-BSP reshapes the ionic fluxes of the main neurotransmitters such as glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid. The testing of this hypothesis requires further study using a larger sample size and a variety of motor tasks.

Conclusion

The goal of this preliminary study was to explore the possibility of using fMRI to investigate the effects of REAC-BSP on brain activity. The results presented in this report provide the basis for further investigations. The findings are encouraging, as they open new perspectives into the ability to study and understand the effects and potential benefits of REAC-BSP upon the electrical activity of the brain.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the technical staff of Diagnostic Imaging Service, Azienda Ospedaliero – Universitaria, Cagliari, Paolo Sirabella for the data analysis with SPM2, and Piero Mannu for his helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Salvatore Rinaldi and Vania Fontani are the inventors of the Radio Electric Asymmetric Conveyor.

References

- 1.Collodel G, Moretti E, Fontani V, et al. Effect of emotional stress on sperm quality. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128(3):254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontani V, Rinaldi S, Aravagli L, Mannu P, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Noninvasive radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation in the treatment of stress-related pain and physical problems: psychometric evaluation in a randomized, single-blind placebo-controlled, naturalistic study. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4(1):681–686. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S24628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A. Radio electric asymmetric brain stimulation in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:207–211. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S23394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A. Long-term treatment of bipolar disorder with a radioelectric asymmetric conveyor. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:373–379. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olivieri EB, Vecchiato C, Ignaccolo N, et al. Radioelectric brain stimulation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with comorbid major depression in a psychiatric hospital: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:449–455. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S23420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Margotti ML. Psychological and symptomatic stress-related disorders with radio-electric treatment: psychometric evaluation. Stress Health. 2010;26(5):350–358. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Mannu P. Psychometric evaluation of a radio electric auricular treatment for stress related disorders: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled controlled pilot study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, et al. Stress-related psycho-physiological disorders: randomized single blind placebo controlled naturalistic study of psychometric evaluation using a radio electric asymmetric treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Moretti E, et al. A new approach on stress-related depression and anxiety: Neuro-Psycho- Physical-Optimization with Radio Electric Asymmetric-Conveyer. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Radio electric treatment vs Es-Citalopram in the treatment of panic disorders associated with major depression: an open-label, naturalistic study. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2009;34(3–4):135–149. doi: 10.3727/036012909803861040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray MA, Minati L, Harrison NA, Gianaros PJ, Napadow V, Critchley HD. Physiological recordings: basic concepts and implementation during functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2009;47(3):1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma R, Sharma A. Physiological basis and image processing in functional magnetic resonance imaging: neuronal and motor activity in brain. Biomed Eng Online. 2004;3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Ferris CF, Febo M, Luo F, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in conscious animals: a new tool in behavioural neuroscience research. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18(5):307–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozcan M, Baumgartner U, Vucurevic G, Stoeter P, Treede RD. Spatial resolution of fMRI in the human parasylvian cortex: comparison of somatosensory and auditory activation. Neuroimage. 2005;25(3):877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibbons RD, Lazar NA, Bhaumik DK, et al. Estimation and classification of fMRI hemodynamic response patterns. Neuroimage. 2004;22(2):804–814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Y, Grova C, Kobayashi E, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Using voxel-specific hemodynamic response function in EEG-fMRI data analysis: an estimation and detection model. Neuroimage. 2007;34(1):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Zwart JA, Silva AC, van Gelderen P, et al. Temporal dynamics of the BOLD fMRI impulse response. Neuroimage. 2005;24(3):667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Mannu P, Margotti ML. Does osteoarthritis of the knee also have a psychogenic component? Psycho-emotional treatment with a radio-electric device vs intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate: an open-label, naturalistic study. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2010;35(1–2):1–16. doi: 10.3727/036012910803860968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Mannu P, Margotti ML. Comparison of two treatments for coxarthrosis: local hyperthermia versus radio electric asymmetrical brain stimulation. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:201–206. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S23130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Mannu P. Radio electric asymmetric brain stimulation and lingual apex repositioning in patients with atypical deglutition: a naturalistic, open-label study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:209–213. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S22830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gountouna VE, Job DE, McIntosh AM, et al. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) reproducibility and variance components across visits and scanning sites with a finger tapping task. Neuroimage. 2010;49(1):552–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fein G, Landman B, Tran H, et al. Statistical parametric mapping of brain morphology: sensitivity is dramatically increased by using brain-extracted images as inputs. Neuroimage. 2006;30(4):1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Logan BR, Rowe DB. An evaluation of thresholding techniques in fMRI analysis. Neuroimage. 2004;22(1):95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nandy R, Cordes D. A semi-parametric approach to estimate the family-wise error rate in fMRI using resting-state data. Neuroimage. 2007;34(4):1562–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, inventors; Rinaldi S, Fontani V, assignees. Radioelectric Asymmetric Conveyor for therapeutic use. 2001 0960475 20010706. European patent. 2006 Oct 11;

- 26.Rinaldi S, Fontani V, inventors; Rinaldi S, Fontani V, assignees. Radioelectric Asymmetric Conveyor for therapeutic use. 7,333,859, 2001. United States patent US patent. 2008 Feb 19;

- 27.Wassermann EM. Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5–7, 1996. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee KH, Hitti FL, Chang SY, et al. High frequency stimulation abolishes thalamic network oscillations: an electrophysiological and computational analysis. J Neural Eng. 2011;8(4):046001. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/4/046001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark VP, Coffman BA, Trumbo MC, Gasparovic C. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) produces localized and specific alterations in neurochemistry: a (1)H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neurosci Lett. 2011;500(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pamenter ME, Hogg DW, Ormond J, Shin DS, Woodin MA, Buck LT. Endogenous GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptor-mediated electrical suppression is critical to neuronal anoxia tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(27):11274–11279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102429108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biedermann S, Weber-Fahr W, Zheng L, et al. Increase of hippocampal glutamate after electroconvulsive treatment: A quantitative proton MR spectroscopy study at 9.4 T in an animal model of depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.580778. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]