Abstract

Mutations in sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2) underlie Darier disease (DD), a dominantly inherited skin disorder characterized by loss of keratinocyte adhesion (acantholysis) and abnormal keratinization (dyskeratosis) resulting in characteristic mucocutaneous abnormalities. However, the molecular pathogenic mechanism by which these changes influence keratinocyte adhesion and viability remains unknown. We show here that SERCA2 protein is extremely sensitive to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which typically results in aggregation and insolubility of the protein. Depletion of ER calcium stores is not necessary for the aggregation but accelerates the progression. Systematic analysis of diverse mutants identical to those found in DD patients demonstrated that the ER stress initiator is the SERCA2 mutant protein itself. These SERCA2 proteins were found to be less soluble, to aggregate and to be more polyubiquitinylated. After transduction into primary human epidermal keratinocytes, mutant SERCA2 aggregates elicited ER stress, caused increased numbers of cells to round up and detach from the culture plate, and induced apoptosis. These mutant induced events were exaggerated by increased ER stress. Furthermore, knockdown SERCA2 in keratinocytes rendered the cells resistant to apoptosis induction. These features of SERCA2 and its mutants establish a mechanistic base to further elucidate the molecular pathogenesis underlying acantholysis and dyskeratosis in DD.

Key words: SERCA2 aggregation, ER stress, apoptosis, Darier disease, keratinocyte

Introduction

Darier disease (DD) is a rare, autosomal, dominantly inherited genodermatosis with complete penetrance and variable expressivity (Godic, 2004; Ringpfeil et al., 2001). Although there is variable expressivity, affected individuals classically develop red-brown hyperkeratotic papules characteristically located on the trunk, scalp, face and neck. Characteristic nail abnormalities, hand and foot lesions and oral white papules are often found in affected individuals. Lesions typically first appear between the ages of 6 and 20 years, and are characterized by wart-like blemishes on body areas with more exposure to heat, humidity and sunlight. Patients often experience itchiness and are troubled by malodors due to frequent skin-lesional infections with bacteria, yeast and dermatophytic fungi (Ringpfeil et al., 2001). Mutations in sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (SERCA2) (Sakuntabhai et al., 1999), a transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which functions in pumping cytosolic calcium into the ER lumen, have been shown to cause DD. There have been reports that people with DD may have neuropsychiatric disorders such as epilepsy, depression and schizoaffective disorders. The neuropsychiatric issues might be explained in part by non-genetic factors, including social isolation attributable to the skin disease (Burge, 1994; Jacobsen et al., 1999; Ruiz-Perez et al., 1999). The fact that SERCA2b is also highly expressed in neurons (Baba-Aissa et al., 1998a) suggests that neuron-related defects might have a role in this disease.

The pathological hallmarks of DD are the loss of desmosomal adhesion (acantholysis) and abnormal keratinization (dyskeratosis). The molecular mechanism by which SERCA2 mutations cause these abnormalities is not known, although previous studies suggest that a depleted ER calcium store might influence the stability and cell surface expression of desmosomal proteins (Muller et al., 2006). DD mutations are the result of missense, nonsense, deletion, insertion and altered splicing variants of the SERCA2 gene. Because few mutant proteins were detected in the soluble portion of Triton X-100 cellular extracts (Ahn et al., 2003), it has been suggested that the mutants were unstable and could be degraded by the proteasome system. Although haploinsufficiency of SERCA2 was proposed to explain the dominant inheritance of DD, the possibility that the genetic defect is caused by gain-of-function mutation has not been tested.

The SERCA pumps in humans are encoded by three genes, ATP2A1, ATP2A2 and ATP2A3. By alternative splicing of their pre-mRNA, the three genes encode up to a total of 10 isoforms that possibly are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (Dode et al., 2003). ATP2A2 encodes three isoforms, SERCA2a, SERCA2b and SERCA2c. SERCA2a is expressed in cardiac muscle (Aubier and Viires, 1998). Relative to SERCA2a, SERCA2b has an extra C-terminal extension and is ubiquitously expressed in non-muscle tissues including skin keratinocytes, cerebellar Purkinjie neurons and hippocampal pyramidal cells (Baba-Aissa et al., 1998a; Baba-Aissa et al., 1998b). SERCA2c is missing exon 7 and is expressed in a pattern similar to SERCA2a (Dally et al., 2006). Compared with SERCA2a, SERCA2b has a twofold higher affinity for Ca2+ and a 50% lower turnover rate for Ca2+ uptake (Lytton et al., 1992; Verboomen et al., 1994). Importantly, SERCA2b expression is induced by diverse ER stressors (Cardozo et al., 2005; Caspersen et al., 2000), suggesting it is responsible for Ca2+ uptake under conditions of cellular stress.

Our results show that SERCA2 mutant proteins were not degraded by proteasomes. Non-degraded mutants formed insoluble aggregates that were located in aggresomes. These aggregates of mutants caused ER stress and apoptosis and certain mutants exacerbated both responses when mutant-expressing cells were exposed to a second ER stressor. By contrast, knockdown SERCA2 increased cell insensitivity to apoptosis induction, a phenomena of dyskeratosis in DD patients. These observations provide a novel interpretation for the acantholytic and dyskeratotic pathogenesis in DD.

Results

ER stress induces SERCA2 aggregation and apoptosis in human primary epidermal keratinocyte HaCaT

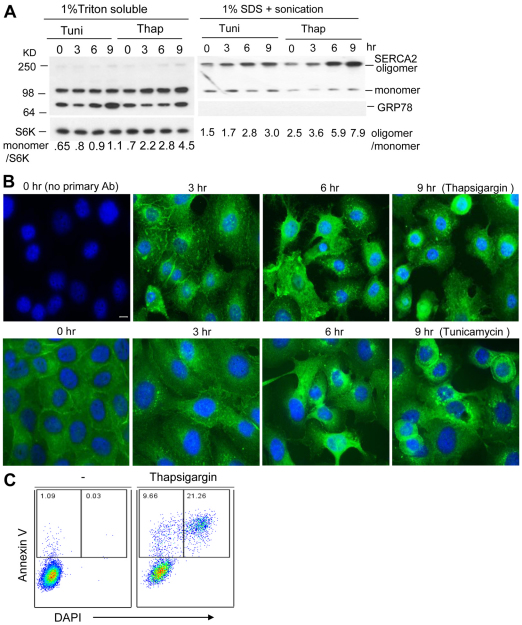

Western blot analysis of SERCA2 revealed two bands, identified as a monomer and an oligomer when resolved by SDS-PAGE loaded with reduced, unheated samples (Fig. 1A). These two bands were routinely seen in western blot analysis of SERCA2, as previously reported (Lytton et al., 1992). The oligomer of SERCA2 can be detected by western blot analysis with a longer transfer. However, oligomers of SERCA2 showed decreasing solubility in 1% Triton X-100 lysis solution with increasing exposures to thapsigargin, an ER stress inducer that is also an inhibitor of SERCA2 (Fig. 1A, right panel). Thapsigargin was more effective than tunicamycin, a N-linked glycosylation inhibitor and promoter of ER stress, at causing SERCA2 oligomer insolubility (Fig. 1A, right panel). The fraction of insoluble SERCA2 oligomers that could be dissolved in 1% SDS with sonication increased with the time of treatment. The two stressors also increased the expression of the SERCA2 monomers as a function of time (Fig. 1A, left panel), which is consistent with reported results obtained from rat neuronal cell line PC12 (Caspersen et al., 2000). The ER stress marker GRP78 was increased in the soluble fraction, demonstrating that both treatments induced ER stress. Staining the thapsigargin-treated cells showed that approximately 30% of the cells were apoptotic (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

ER stress induces SERCA2 aggregation and apoptosis. (A,B) ER stressors induce the death of keratinocyte HaCaT cells as SERCA2 protein aggregation increases. The HaCaT cells cultured in a 24-well plate were treated with 1 μM thapsigargin or 1 μg/ml tunicamycin, for the indicated times in DMEM medium containing 2% FBS. At the end of treatment, 12 wells of cells were lysed for extracting the fraction soluble in 1% Triton X-100 and then the remaining insoluble fraction was solubilized with 1% SDS plus sonication. The SERCA2 and GRP78 proteins were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE loaded with reduced, non-heated samples and detected by western blotting of each soluble fraction (A). The S6K (p70 S6 ribosomal kinase) protein was used as a loading control. The other 12 wells of the cells grown on coverslips were fixed with methanol and stained using Alexa-Fluor-488-linked SERCA2 antibody (B). (C) ER stress induces keratinocyte apoptosis. The cells were treated with 1 μM thapsigargin or vehicle control for 12 hours. Cell apoptosis and death were detected by flow cytometry after the cells were stained with FITC–annexin V (for apoptosis) and the nuclear dye DAPI (for death).

In immunocytochemical analysis of the immortalized primary keratinocyte cell line, HaCaT (Fig. 1B), SERCA2 proteins were diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm and appeared to be focused within the cell boundaries under normal culture conditions (Fig. 1B, 0 hours, no stress). However, 3 hours after stimulation with thapsigargin SERCA2 proteins were found in small aggregates or clumps in the cytoplasm or accumulated around the nuclei of the affected cells (Fig. 1B). At this time point, cells treated with tunicamycin looked moderately affected. Both SERCA2 proteins and cellular morphology were grossly perturbed by 6 hours of stimulation with either thapsigargin or tunicamycin (Fig. 1B). The keratinocyte layer was largely destroyed by either treatment after 9 hours exposure, with many rounded dying cells detached from the culture plate. The sensitivity of the cells to tunicamycin was less than to thapsigargin, indicating that deficiency in SERCA2 function enhances SERCA2 aggregative sensitivity to ER stress (Fig. 1B). The breached keratinocyte layer caused by ER stressors resembles the phenomena observed in the skin lesions of DD patients. However, the question remains as to what is the source of ER stress and why SERCA2 aggregates in DD.

Missense mutants of SERCA2 gene are insoluble and ubiquitinylated, but not degraded by proteasomes

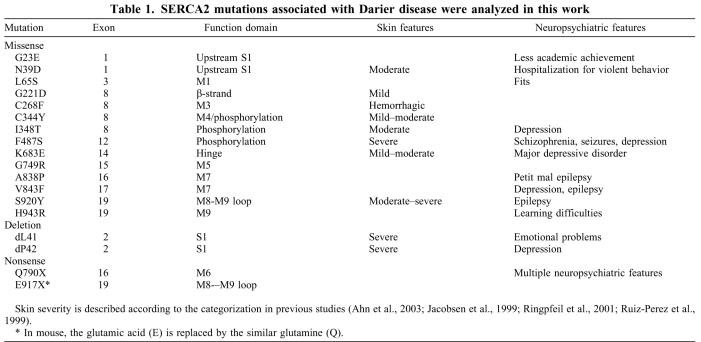

To explore the source of ER stress and SERCA2 aggregation in DD, we chose to study SERCA2 mutants. SERCA2a and SERCA2b are encoded by the same ATP2A2 gene; SERCA2b is ubiquitously expressed and all SERCA2 mutants identified to date are of this isoform. Mouse Serca2 has more than 98% identity to human SERCA2 at the amino acid level. To explore the potential dominant function of ATP2A2 mutations, we used site-directed mutagenesis to generate naturally occurring mutations known to cause skin lesions and neuropsychiatric disorders, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

SERCA2 mutations associated with Darier disease were analyzed in this work

Cellular extracts using 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer have reduced amounts of SERCA2 mutants compared with the wild-type protein (Ahn et al., 2003). To test the steady state production and solubility of SERCA2 variants, wild-type (WT) SERCA2 and various missense mutants (shown in Fig. 2A) were transiently transfected into human kidney HEK293 cells instead of HaCaT cells, because it is extremely difficult to transfer genes into keratinocytes. Western blots showed that with the exception of the L65S, C268F, C344Y and V843F mutants, the mutant SERCA2 proteins appeared insoluble in the 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer (Fig. 2B). When comparing heat-denaturated (95°C, 3 min) samples with samples that were not heat treated (Fig. 2B,C), we found that the heating enhanced the amount of the oligomer of the WT and the relatively soluble mutants but not the insoluble mutants, indicating that intrinsic protein misfolding, not any extrinsic condition, causes the insolubility of SERCA2 mutants. Overexpression of WT SERCA2 did not elicit protein misfolding because the ratio of the amount of oligomer to monomer of the WT proteins was decreased compared with that of the mutants (Fig. 2C). Anti-FLAG antibody can recognize ectopically expressed FLAG-tagged SERCA2 as well as an unrelated protein (non-specific band) shown with the empty vector transfectant (Fig. 2B). Similar to endogenous SERCA2, SERCA2–FLAG was resolved as an oligomer and a monomer by SDS-PAGE loaded with reduced, non-heated samples. The expression of SERCA2 and its mutants in Neuro2a cells showed a similar pattern to that in HEK293 cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Naturally occurring SERCA2 mutant proteins are minimally detected in the Triton-soluble fraction. (A) A diagram of the SERCA2 sequence depicting the location of the mutants studied in DD patients. (B,C) Ectopic expression of wild-type (WT) and mutant SERCA2. FLAG-tagged mutant and WT SERCA2 expression plasmids at a concentration of 0.25 μg/per well (B) or 0.1 μg/per well (C) in a 24-well plate were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. 36 hours (B) or 24 hours (C) after transfection, the cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 buffer and the resulting supernatants were resolved by SDS-PAGE loaded with reduced, heated samples (B) or reduced, non-heated (C) samples. Anti-FLAG antibody was used for the western blots. After being washed, the same membrane was blotted with anti-β-actin as the loading control.

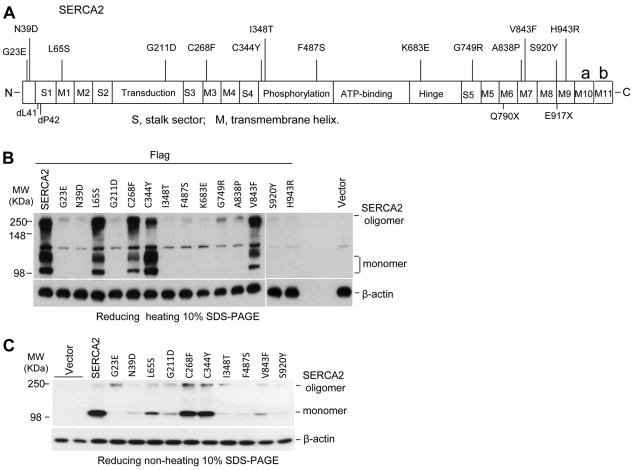

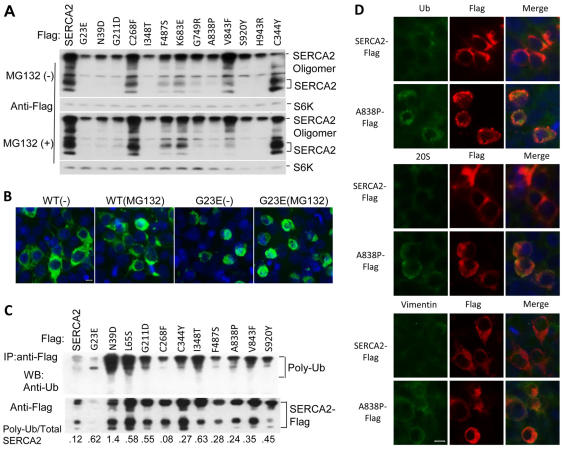

Generally, reduced levels of a protein in a Triton X-100 supernatant can result from three processes: nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD), degradation by proteasomes and formation of detergent-insoluble aggregates. To measure the proteasome-mediated degradation of these missense mutants, the transfected cells were treated with MG132, a commonly used proteasome inhibitor. Treatment with MG132 did not increase the amount of the mutant proteins (Fig. 3A), indicating most expressed mutants were not actively degraded by the proteasome. Partial degradation occurred in some mutants such as G23E, N39D, S920Y and H943R; however, blocking degradation with MG132 increased the number of rounded cells expressing mutant proteins that were aggregated and accumulated around the nuclei (Fig. 3B). By contrast, 2- to 14-fold more polyubiquitinylated aggregates were found of the mutant SERCA2 proteins than of the WT SERCA2 (Fig. 3C). The mutant C268F had the lowest ratio of polyubiquitinylation of any of the mutants, and this was also lower than seen for WT SERCA2 (Fig. 3C). Polyubiquitinylated mutants appeared to accumulate in the aggresome, supported by colocalization of the FLAG tag with ubiquitin, proteasome component 20S and vimentin (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

SERCA2 mutants are polyubiquitinylated and form aggregates in the aggresome. (A,B) Mutants were not degraded by proteasomes. HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged expression plasmids of WT or mutant SERCA2 for 24 hours before treatment or no treatment with 2.5 μM MG132 for an additional 16 hours. Anti-FLAG antibody was used to detect the expression of WT and mutant proteins by western blotting (A) or immunostaining (B). (C) Polyubiquitinylation of SERCA2 mutants. After 36 hours of transfection with FLAG-tagged WT or mutant SERCA2 expression plasmids, the cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 and supernatants were immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG antibody. Anti-ubiquitin blotting detected polyubiquitinylated proteins in immunoprecipitates. Densitometric quantification of respective polyubiquitin relative to total protein of WT or mutant SERCA2 is shown in the bottom of the panel. (D) Mutant proteins form aggregates in aggresomes. HEK293 cells were transfected with 0.1 μg/ml FLAG-tagged WT or mutant SERCA2 expression plasmids for 24 hours. Then the transfected cells were fixed and double stained with antibodies to mouse FLAG and to each of the following proteins: rabbit ubiquitin (Ub), 20S proteasome, or goat vimentin. Representative results from mutant A838P are shown.

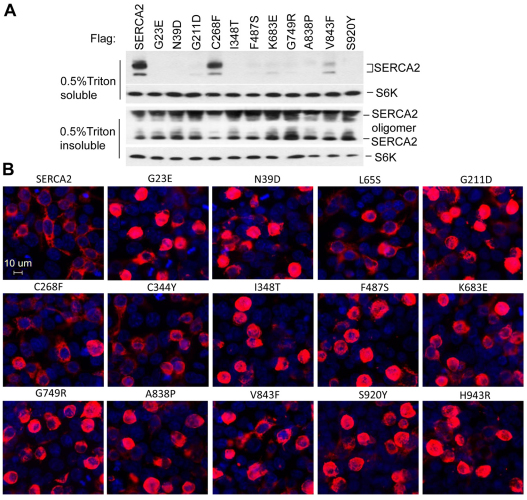

We examined the solubility of the mutant proteins and observed that most tested mutants could not be dissolved in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Fig. 4A, top panel), but could be partially dissolved in 1% SDS lysis buffer with sonication (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). Consistent with their reduced solubility in 1% Triton X-100 lysis solution (Fig. 2B), the C268F and V843F mutants were also partially soluble in 0.5% Triton X-100, to different extents; V843F solubility was less in 0.5% than 1% Triton X-100 buffer (compare Fig. 4A and Fig. 2B). This demonstrated that some mutants were expressed at a similar level to the wild-type protein, but had reduced solubility in Triton X-100 lysis buffer, consistent with their status as misfolded, ubiquitinylated and aggregated proteins. Comparison of the solubility of the mutants to their ubiquitinylation status suggests that misfolding and insolubility of the mutants were not tightly correlated with ubiquitinylation status. The reason could be that ubiquitinylated insoluble mutant proteins were not sufficiently dissolved to be detectable.

Fig. 4.

SERCA2 mutants are insoluble, aggregated and alter cell morphology. (A) Insolubility of SERCA2 mutants. HEK293 cells were sequentially lysed with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Triton soluble) and 1% SDS with sonication (Triton insoluble) 24 hours after transfection. Anti-FLAG and anti-S6K blots visualized SERCA2 and the internal control, S6K, proteins, respectively. (B) Aggregation and morphological alteration of cells by SERCA2 mutants. 40 hours after transfection with FLAG-tagged WT or mutant SERCA2 expression plasmids, the HEK293 cells were fixed with methanol, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, and stained with Cy3-conjugated FLAG antibody. Empty vector transfectants showed no staining. Merged images of the Cy3-conjugated FLAG staining and the DAPI nuclear dye are shown.

To visualize the expression patterns of these mutants, we stained the transiently transfected HEK293 cells expressing FLAG-tagged WT or mutant forms of SERCA2. Cells transfected with WT SERCA2 retained almost normal morphology. By contrast, cells transfected with most DD-associated SERCA2 mutants assumed a rounded cell morphology resembling acantholytic keratinocytes, and contained small clumps or large aggregates of FLAG-tagged proteins located around the nuclei (Fig. 4B). The cells expressing the mutants that were only partially soluble in the Triton X-100 buffer (including L65S, C268F and V843F) had an intermediate phenotype, with more rounded cells expressing the clumped mutant SERCA2 than WT, but with fewer rounded cells than for other insoluble mutants (Fig. 4B). These results further demonstrated that expression of SERCA2 mutants that are insoluble in Triton X-100 was directly correlated with the induction of rounded, acantholytic, apoptotic cell morphology and the formation of intracellular aggregates of polyubiquitinylated SERCA2. These mutants were poorly degraded by proteasomes and accumulated in structures of sequestered, clumped proteins termed aggresomes (Johnston et al., 1998; Olzmann et al., 2008).

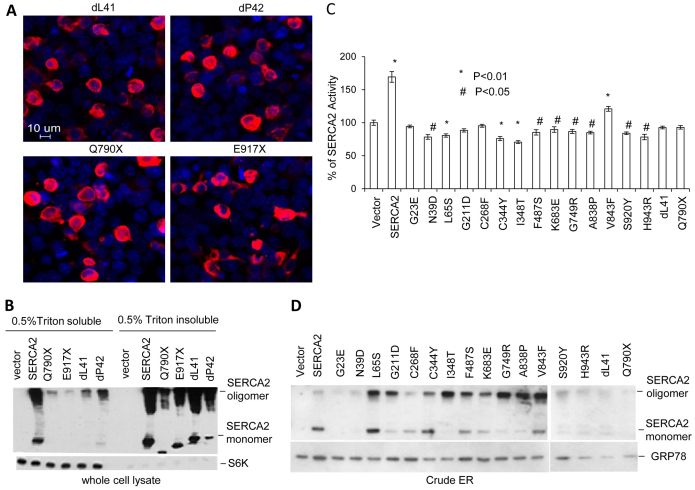

Deletion and nonsense mutants of SERCA2 are not degraded and form insoluble aggregates

Of the 122 mutations identified in ATP2A2 in DD patients, 46% are missense, 12% nonsense, 35% deletion–insertion and 11% alter mRNA splicing (Godic, 2004). The non-missense and deletion mutations give rise to truncated proteins. To test if these mutants are also misfolded, we chose two nonsense mutations and two inframe deletions with features summarized in Table 1. Deletion of leucine 41 or proline 42 of WT SERCA2, named dL41 and dP42, resulted in mutant proteins that were mainly distributed perinuclearly. The cells that expressed these mutants were rounded with perinuclear aggregates (Fig. 5A). Similar to the deletion mutants, nonsense mutants of Q790X and E917X accumulated in perinuclear aggregates (Fig. 5A). Western blots confirmed the expected molecular mass of these mutants (Fig. 5B). Consistent with the aggregate formation, these mutants were insoluble in 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer although sonication in 1% SDS could partially dissolve these insoluble aggregates (Fig. 5B). Compared with WT SERCA2 and deletion mutants, the nonsense mutants were not completely stable because low amounts of truncated proteins were detected in the Triton-X-100-insoluble fraction. These data suggest that similar to the missense mutations, the deletion and nonsense mutants of SERCA2 generated insoluble truncated proteins that were also misfolded, aggregated and barely degraded. Possibly, insoluble, undegradable aggregates of SERCA2 mutants carried by DD patients could be a common pathogenic factor in DD development, whether caused by missense, nonsense or deletion mutations. Evidence to support this assumption is that the effect of these mutants on endogenous SERCA2 activity is less than 30% (Fig. 5C). This indicates that there is no apparent correlation between the altered ER calcium storage and mutant-induced ER stress; in addition, this shows that deficiency of one SERCA2 allele is not the leading cause for the development of the dominantly inherited disease. The measurement of SERCA2 activity is consistent with a previous report (Ahn et al., 2003). The effect of these missense mutants on endogenous SERCA2 function is direct as they were expressed in the ER, although expression of some mutants in the ER was lower than that of the WT protein (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Deletion and nonsense mutations of SERCA2 alter cell morphology and form aggregates. (A) Morphologic alteration and aggregate formation of the indicated SERCA2 mutants. HEK293 cells were transfected with expression plasmids of FLAG-tagged deletion or nonsense mutants for 36 hours and then stained with Cy3-conjugated FLAG antibody. (B) Insolubility of deletion and nonsense mutants. The same set of transfectants as in A was fractioned with 0.5% Triton X-100 lysis buffer into supernatant and pellet. The pellet was then washed and dissolved in 1% SDS loading buffer and sonicated. Western blotting detected the mutant proteins in the two fractions. The internal S6K bands acted as a loading control. (C,D) Activity of SERCA2 mutants in microsomes. HEK293 cells transfected with expression plasmids of WT or each mutant SERCA2 for 24 hours were subjected to microsome isolation, and SERCA activity was determined as described in the Materials and Methods. SERCA2 activity is represented as a percentage of endogenous SERCA activity that was arbitrarily set at 100. The parallel isolated microsomes were directly lysed with 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer and resolved by a reducing non-heated SDS-PAGE. Western blots using antibodies to FLAG and GRP78 showed the expression of FLAG-tagged proteins and the ER-resident protein GRP78 (D).

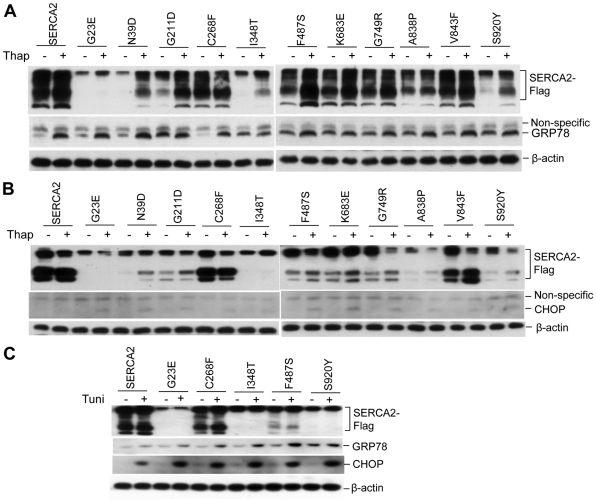

SERCA2 mutants elicit ER stress and induce apoptosis

Cells with insufficiently eliminated aggregates of misfolded proteins will provoke ER stress and activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), thereby inducing apoptosis if the UPR is prolonged and the ER stress is not alleviated (Bernales et al., 2006; Rutkowski and Kaufman, 2004). ER stress is characterized by increased levels of ER stress markers including ER resident chaperon GRP78 and transcriptional factor C/EBP homologous protein (growth arrest and DNA damage protein 153, also known as CHOP, GADD153 and DDIT-3) (Jiang and Wek, 2005). We transiently transfected WT SERCA2 or its missense mutants into HEK293 cells and measured GRP78 and CHOP levels in the transfectants after treatment with or without stress stimulator thapsigargin (Treiman et al., 1998). As shown in Fig. 6A, GRP78 protein levels were significantly increased in many mutant-expressing cells (except for mutant C268F) compared with WT SERCA2 cells. Further stressing the transfected cells with thapsigargin enhanced GRP78 levels to a varied extent depending on the mutant. Thapsigargin treatment dramatically increased GRP78 levels in WT and G23E, N39D and C268F mutant cells that had endured weak ER stress, but did not increase the already high GRP78 levels in cells expressing the other SERCA2 mutants (Fig. 6A). HEK293 cells transfected with the C268F mutant expressed GRP78 and responded to thapsigargin slightly more than to WT transfections. The mutant proteins did not elicit detectable expression of the proapoptotic protein, CHOP. However, consistent with the observed changes in GRP78 levels, CHOP was induced after thapsigargin treatment in cells transfected with most of the missense SERCA2 mutants. The induction of CHOP was much less in cells transfected with WT SERCA2 than in cells transfected with all mutants tested (Fig. 6B). To test whether increased GRP78 and CHOP levels in response to the mutant SERCA2 proteins depended on ER calcium depletion by thapsigargin, we used tunicamycin to stimulate ER stress in the transfected HEK293 cells. Similar to thapsigargin, tunicamycin induced an increase in GRP78 in the cells expressing the mutants G23E, C268F, I348T, F487S and S920Y; however, tunicamycin increased CHOP to much higher levels in these mutant-transfected cells than did thapsigargin (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that expression of the mutants is largely unable to activate UPR at baseline, but results in full UPR activation in the presence of other ER stressors.

Fig. 6.

Insoluble SERCA2 mutants elicit ER stress and exacerbate the response to ER stressors. (A–C) The ER stress marker GRP78 is increased in HEK293 cells expressing insoluble mutants. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids of FLAG-tagged SERCA2 or the indicated mutant proteins. 24 hours after transfection, the cells were treated with 2 μM thapsigargin for an additional 8 hours (A), 10 hours (B), or with 2 μg/ml tunicamycin for 8 hours (C). Immunoblots show the expression levels of the indicated proteins, and β-actin served as a loading control.

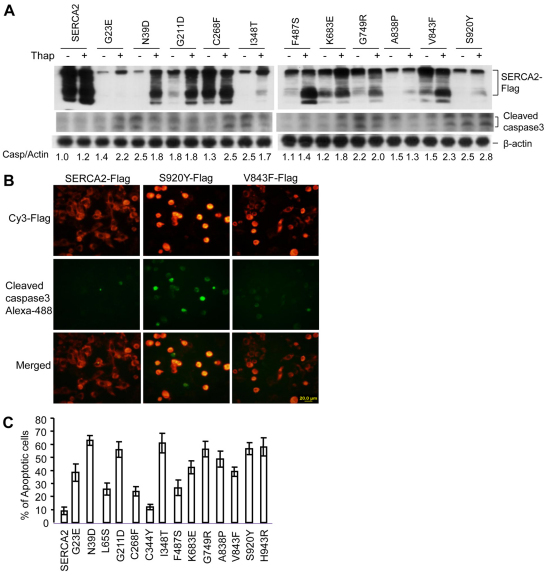

To determine whether SERCA2 mutants induce apoptosis, we measured the levels of the apoptotic final executor, cleaved caspase-3, in mutant-expressing HEK293 cells using western blotting and immunofluorescence. As seen in Fig. 7, transfection of most of the mutants resulted in increased levels of activated caspase-3 compared with the effect of WT SERCA2 (1.5- to 2.5-fold at baseline), with smaller increases (1.1- to 1.5-fold) seen in cells transfected with G23E, C268F, F487S, K683E and V843F. Those mutant-transfected cells that had higher levels of activated caspase-3 at baseline exhibited minimal increases in activated caspase-3 when treated with thapsigargin (Fig. 7A). However, the mutant-transfected cells with lower caspase to actin ratios showed significantly enhanced caspase-3 activity in response to thapsigargin treatment. Consistent with the western blot results, double immunostaining of transiently transfected cells with antibodies to FLAG tag and active caspase-3 showed that most of the rounded-up mutant cells were undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 7B). The percentage of apoptosis varied for each of the mutants but all caused more apoptosis than did transfection with WT SERCA2 (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, the degree to which a SERCA2 mutant promoted apoptosis appeared to correlate with its insolubility. Activated caspase-3 levels were not correlated with increased pre-apoptotic CHOP levels in the mutant-expressing cells. Possibly these SERCA2 mutants induce apoptosis through mechanisms that are not always dependent on CHOP.

Fig. 7.

Insoluble SERCA2 mutants induce apoptosis. (A) Western blot showing that caspase-3 was activated by SERCA2 mutants. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 hours and then treated with 2 μM thapsigargin for another 12 hours. The relative ratio of densitometrically quantified cleaved caspase-3 to β-actin is showed at the bottom, in which the ratio of untreated WT SERCA2 to β-actin was defined as 1.0. (B) Immunofluorescent staining shows that transfected mutant SERCA2 activated caspase-3. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids of WT or mutant SERCA2. After 40 hours, the cells were fixed using methanol, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 and double stained with mouse Cy3-conjugated anti-FLAG and rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibodies followed by anti-rabbit Alexa-Fluor-488 antibody. (C) Percentage of apoptotic cells of transfectants. The percentage of apoptotic cells were derived from the ratio of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells per 300 FLAG-positive HEK293 cells.

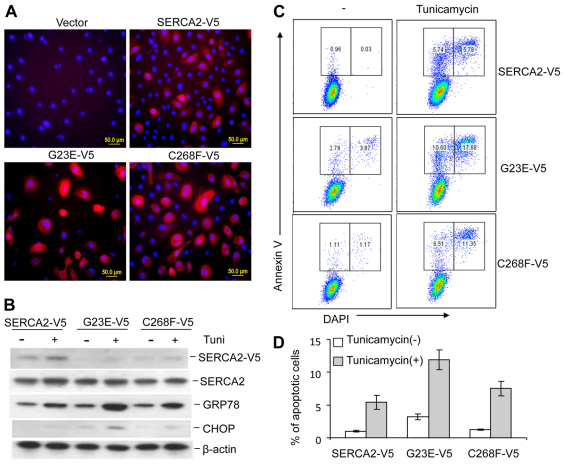

SERCA2 mutants induce ER stress in primary human epidermal keratinocytes and exacerbate the response to ER stressor treatment

To study the effect of SERCA2 mutants in human epidermal keratinocyte (HEKa) cells, we chose two representative mutants, insoluble G23E and soluble C268F, and transduced them into HEKa cells by lentiviral delivery. After transduction, some cells expressing mutant proteins appeared to detach from the culture plate. Immunofluorescence analysis suggested that the mutant proteins were expressed at higher levels than WT SERCA2, and resulted in altered morphology (Fig. 8A). Additionally, after blasticidin selection, the drug-resistant mutants G23E and C268F also increased the levels of GRP78 and CHOP above that in WTSERCA2-transfected cells. The mutant-expressing HEKa cells were more sensitive to ER stress induction than were HEK293 cells because UPR activation was observed during the static stage and even in WT-like soluble C268F-infected cells (Fig. 8B). Tunicamycin treatment enhanced the UPR response in both mutant- and WT SERCA2-infected cells (Fig. 8B). Flow cytometry indicated that the mutants G23E and C268F induced more cell death than did the WT SERCA2 (Fig. 8C). In all three cases tunicamycin treatment greatly enhanced apoptosis (Fig. 8D). In either the presence or absence of tunicamycin, the mutant G23E increased apoptosis compared with WT SERCA2 (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that SERCA2 mutations might induce apoptosis and death (acantholysis) of keratinocytes in DD patients.

Fig. 8.

Primary human adult epidermal keratinocytes (HEKa) expressing mutant SERCA2 are sensitive to ER stress induction, apoptosis and death. (A) Expression of WT and mutant SERCA2 in HEKa cells. HEKa cells at approximately 50% confluency were transduced with lentivirus carrying empty vector, SERCA2, G23E or C268F. The cells were cultured for 4 days after transduction then stained with mouse anti-V5 antibody followed by Texas Red anti-mouse IgG. (B) SERCA2 mutants induce ER stress. Two days after lentiviral infection, transfected HEKa cells were selected with 6 μg/ml blasticidin and drug-resistant cells were treated with 2 μg/ml tunicamycin for 8 hours. Total cells, including the detached cells in the culture medium, were collected and lysed for western blotting to detect ER stress. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (C) SERCA2 mutants enhanced HEKa apoptosis and death induced by tunicamycin. After the same treatment procedure as in B, cells were collected and cell apoptosis and death were detected by flow cytometry after the cells were stained with FITC-annexin V (for apoptosis) and DAPI (for death). (D) Summary of the annexin-V-positive proportion from three separate experiments performed as described in C.

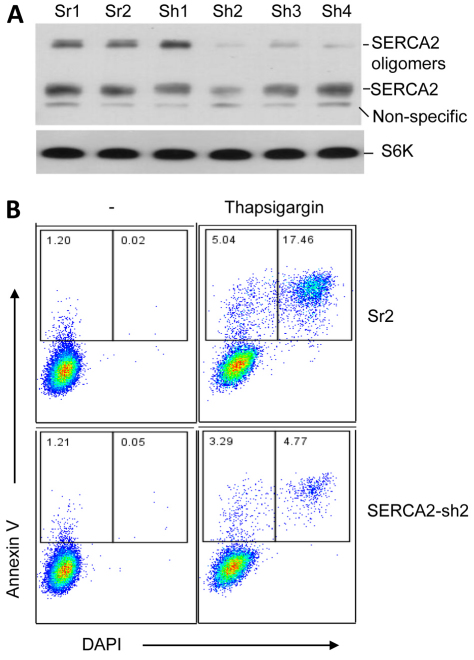

Knockdown of SERCA2 renders keratinocytes resistant to apoptosis induction

Because SERCA2 protein is very sensitive to ER stress stimulation, which results in SERCA2 self aggregation, we hypothesized that knockdown of SERCA2 protein in keratinocytes could elevate the sensitivity threshold for the apoptosis induction by ER stress. This would explain the phenomena of dyskeratosis in DD where SERCA2 proteins are insufficient, either because of the partial or complete degradation of those mutants by proteasomes, or the aggregation of the WT SERCA2 protein induced by mutant-elicited ER stress. To test the hypothesis, we silenced SERCA2 by up to 70–80% in the keratinocyte line HaCaT. We treated the SERCA2-silenced [using short hairpin (Sh) RNA] cells with thapsigargin and found that these cells were resistant to apoptosis induction (Fig. 9B). This result is consistent to the one showing that heterozygous Serca2 knockout mice are predisposed to squamous cell carcinomas (Liu et al., 2001). Although SERCA2 insufficiency can be compensated for by increase of the Golgi calcium pump protein ATP2C1 (Foggia et al., 2006), this compensation might increase the cell insensitivity to ER stress induction. Therefore, our data show that the aggregation and degradation of mutant SERCA2 is a cause of acantholysis and dyskeratosis, two hallmarks of the DD phenotype.

Fig. 9.

Knockdown of SERCA2 in keratinocytes renders the cells resistant to apoptosis induction. (A) Efficacy of SERCA2 short hairpin siRNAs (Sh). HEK293 cells were co-transfected with SERCA2–FLAG plasmid and the plasmids for scrambled (Sr) or SERCA2 shRNAs for 24 hours. The efficacy was determined by western blot using anti-FLAG antibody. (B) Silencing SERCA2 increased the resistance of the cells to apoptosis induction by thapsigargin. HaCaT cells were transduced with lentivirus carrying SERCA2-Sh or SERCA2-Sr, and selected with 8 μg/ml blasticidin during 2 weeks in cell culture. The drug-resistant cells that were more than 95% EGFP positive were treated with 1 μM thapsigargin for 12 hours. Flow cytometry detected the percentage of annexin V (for apoptosis) and nuclear dye DAPI (for death). Representative flow cytometry graphs of three separate experiments are shown.

Discussion

Darier disease is caused by mutation of the gene encoding SERCA2. There is another calcium ATPase residing in the Golgi apparatus, ATP2C1, which is mutated in Hailey–Hailey (H–H) disease, a condition that shares histological and sometimes clinical features with DD. Mutations of the SERCA2 and ATP2C1 genes lead to a reduction in their calcium pump activity in vitro (Ahn et al., 2003) and to the moderate depletion of calcium stores in the keratinocytes of patients with either disease (Foggia et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2000; Leinonen et al., 2005). Although haploinsufficiency has been considered to lead to the development of both diseases, a dominant function of the mutants has not been tested. Our data show that by exacerbating UPR, the mutations observed in the DD patients can directly trigger pathological processes. Although calcium pump activity deficiency due to SERCA2 mutation correlated with the sensitivity and severity of SERCA2 aggregation, the causative mechanism of DD depends on the mutation of SERCA2 itself, which elicits ER stress possibly to drive the malfunctioning aggregation of the other WT allele-encoded SERCA2 proteins. Although we showed that SERCA2-mutation-elicited ER stress initiates SERCA2 aggregation, other stress factors might play a role in exacerbating the effects seen in DD. The fact that heterozygous Serca2 knockout mice do not exhibit any DD features supports the role of gain-of-function mutations in the pathogenesis of DD (Liu et al., 2001; Okunade et al., 2007).

Our systematic analysis of the naturally occurring mutations suggests a general mechanism by which the mutations cause DD. Almost all the mutant proteins we tested accumulated as insoluble aggregates that were poorly degraded by proteasomes. Moreover, the mutant proteins were able to trigger and enhance the UPR and apoptosis in primary human epidermal keratinocytes. Our data are consistent with a recent report showing the upregulation of the ER stress markers GRP78 and CHOP in DD skin lesions (Onozuka et al., 2006). Surprisingly, expression of mutant SERCA2 provokes a UPR response that both stimulates the growth (dyskeratosis) and induces the apoptosis (acantholysis) of affected keratinocytes. One explanation is that at an early stage of ER stress there is an increased expression of GRP78 protein that prevents aggregation of mutant and wild-type SERCA2 proteins and also elicits an adaptive response for affected keratinocyte survival. By contrast, if late stage ER stress occurs because of the presence of the mutant proteins and/or environmental factors, then CHOP proteins are induced to promote keratinocyte apoptosis. Owing to the heterogeneity of keratinocytes in the epidermal basal cell layer and the sensitivity to ER stress induction, dyskeratosis and acantholysis are observed simultaneously in the skin lesions of DD patients.

Another implication of our study is that it might offer a potential explanation for the neuropsychiatic symptoms reported in DD patients. Because the mutant proteins are also expressed in neurons, we speculate that accumulation of the insoluble aggregates might be an underlying cause of the neuropsychiatic symptoms. Our data suggest an intriguing correlation between the insolubility of SERCA2 mutant proteins and neurodisorders reported in DD patients (Table 1). Even for relatively soluble mutants such as L65S, C268F and C344Y that weakly elicit ER stress at static stages in HEK293 cells, mutant-expressing primary HEKa cells show increased ER stress during static stages and are vulnerable to apoptosis upon exposure to additional cellular stresses. For patients with such mutations, secondary environmental factors could play important roles in the onset of cutaneous and neurological pathologies. Therefore, environment factors such as sunlight, infection, sweating and irradiation exacerbate the skin symptoms of DD. Although secondary factor effect on the neurological pathology remains to be tested, it has the simplicity of shared pathogenesis with other neurodegenerative diseases. Misfolded protein accumulation in aggresomes due to impairments of proteasome function are documented causes of neurodegenerative diseases (Olzmann et al., 2008). Our recent report on the aggregation of laforin mutant proteins suggests that epilepsy in DD patients might also be attributable to this mechanism (Liu et al., 2009).

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

The following antibodies and reagents were used: mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for SERCA2 (2A7-A1, Abcam; for western blotting), V5 (Invitrogen), ubiquitin (P4D1; Santa Cruz), GRP78/Bip (BD Transduction Laboratories), S6K (H-9; Santa Cruz), FLAG (M2; Sigma), FLAG-Cy3 (Sigma), β-actin (Sigma) and CHOP/GADD153 (MA1-250; Thermo Scientific); rabbit antibodies to SERCA2 (NB100-237; Novus), cleaved caspase-3, 20S proteasome (Biomol), polyubiquitin (Ubi-1; Thermo Scientific), and goat antibody to vimentin (AB1620; Millipore) for immunofluorescence staining. Thapsigargin, tunicamycin and MG132 were purchased from Sigma. EpiLife medium (M-EPI-500-CA) and supplement (HKGS, S-001-5) were bought from GIBCO, Cascade Biologics. The immortalized human primary epidermal keratinocyte line HaCaT came from Dr. James Varani, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School.

Plasmids and RT-PCR

The coding region of mouse Serca2b cDNA was amplified by PCR using reverse transcripts of freshly isolated C57BL/6J mouse brain mRNA as template, and cloned into a pcDNA vector with a FLAG tag at the N-terminus of Serca2b, named SERCA2 in the text. After sequencing confirmation of the wild-type Serca2b, all mutants studied were made by site-directed mutagenesis using Serca2b as a template, and confirmed by sequencing again. SERCA2, G23E and C268F were subcloned from their pcDNA plasmids into a lentiviral vector of pLenti6/V5-TOPO (Invitrogen) after the lentiviral vector was modified. The V5 tag was fused into the C-terminal sequence of SERCA2 or its mutants. The sequence of the most effective silencer of SERCA2 used was: Sh2: 5′-tactgagatcggcaagatc-3′.

Transfection and lentivirus preparation

Generally, human embryonic kidney, HEK293, cells were transiently transfected with a total of 0.1–0.25 μg plasmid/per well and 0.3–0.75 μl lipofectman-2000/per well in a 24-well plate for 24–36 hours in Opti-MEM (minimal essential medium) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. To prevent cells from detaching when the culture medium was changed to 0.5 ml Opti-MEM medium, one third of the original culture medium was not removed. Overnight-passaged cells grown to approximately 75% confluence were used for transfection. Lentiviral vectors of SERCA2 or its mutants were transfected into HEK293FT cells according to the lentiviral preparation instructions (Invitrogen). The lentivirus was made in a 150 mm Falcon culture dish and 50 ml medium was collected and centrifuged at 550 g for 10 minutes to remove cell debris. Viral particles obtained after centrifugation at 12,857 g overnight were suspended with 2 ml of 10% FBS DMEM and stored at −70°C. 50–100 μl of concentrated virus per well of 6-well plates was used for the transduction in a culture medium containing 6 μl/ml polybrene. 24 hours after transduction, the infected cells were grown in culture for another 1–2 days before use.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

Transfected cells were lysed with pH 7.4 lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5% or 1% Triton X-100, protein and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) at 1:100 dilution. Supernatants of cell lysates were subjected to reducing, heated (95°C for 3 minutes) or non-heated 10% SDS-PAGE. Membrane transfer was performed in a semi-dry transfer machine (Bio-Rad) at 100 mA for 3 hours. To allow for high transfer efficiency of protein aggregates, the transfer was conducted in two transfer buffers: the bottom buffer contained 60 mM Tris-HCl, 40 mM N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid (CAPS), 15% methanol, and the top buffer contained 60 mM Tris-HCl, 40 mM CAPS, 0.05% SDS. Supernatants of the lysate also were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) after pre-incubation with protein G beads for 2 hours. The cleared supernatant was immunoprecipitated, rotated overnight at 4°C, then captured by protein G beads with a 4 hour rotation at 4°C. Following intensive washing with 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer, the IP complex was dissolved in SDS loading buffer and run in a 10% SDS-PAGE.

Immunofluorescence

Twenty-four hours after transfection, HEK293, HaCaT or HEKa cells were treated or not with vehicle (DMSO) or 2 μM thapsigargin or tunicamycin for 8 hours and fixed with methanol. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, stained with primary mouse antibody to V5 or FLAG, rabbit antibody to SERCA2, ubiquitin or 20S, or goat antibody to vimentin. Secondary antibodies, anti-mouse Texas Red, anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 or anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 were used for detection.

Primary human epidermal keratinocyte, adult (HEKa) culture and transduction

The HEKa cells were from Gibco and cultured in EpiLife medium with supplements as described by the manufacturer. Second to third passaged HEKa cells were cultured in a 25 cm flask or in a 6-well plate to approximately 70% confluency, and then transduced with lentivirus for 24 hours. The transduced HEKa cells were cultured in fresh medium for an additional 1–2 days before use in experiments.

Isolation of microsomes

Microsomes (crude ER) were isolated by a serial centrifugation according to previously described procedures (Li et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2000). Briefly, HEK293 cells cultured in 6-well plates were transiently transfected with WT SERCA2 or its mutants for 24 hours. After that, the cells were trypsinized and suspended with 350 μl of low-tonic buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM MgCl and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. The cells were homogenized with a glass homogenizer for 45 strokes and then made isotonic by the addition of 350 μl buffer containing 0.5 M sucrose, 0.3 M KCl, 6 mM βmercaptoethanol, 40 μM CaCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. The fractionation was performed according to Parsons's protocol except for the last centrifugation, for which 20,000 g for 3 hours was used instead of 100,000 g for 1 hour. The pellets (microsomes) were suspended in 65 μl buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.15 M KCl, 0.25 M sucrose, 20 μM CaCl2 and 3 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The Lowry assay was used for protein determination of 10 μl of the microsome solution.

Measurement of SERCA2 activity in microsomes

SERCA2 activity was measured using an enzyme-coupled spectrophotometric assay as previously described (Li et al., 2004). The reaction was started by adding 25 μl microsomes (equal to 5 μg protein) to 75 μl of assay buffer in the absence (total activity) or presence (activity of thapsigarin-insensitive calcium pumps) of 5 μM thapsigargin, and was incubated at 30°C for 60 minutes. The assay buffer contained 25 mM MOPS-KOH, 120 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.45 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 1.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.32 mM NADH, 5 IU/ml pyruvate kinase, 10 IU/ml lactate dehydrogenase, 2 μM calcium ionophore A23187 and 5 mM sodium azide, a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial function (Solaro and Briggs, 1974). The depletion of NADH was detected by spectrophotometric absorption at 340 nm. The SERCA2 activity was calculated by subtracting the activity of thapsigargin-insensitive calcium pumps from the total calcium pump activity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Judith Connett for her assistance in revising the English of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number 1R21NS062391]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Ahn W., Lee M. G., Kim K. H., Muallem S. (2003). Multiple effects of SERCA2b mutations associated with Darier's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20795-20801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubier M., Viires N. (1998). Calcium ATPase and respiratory muscle function. Eur. Respir. J. 11, 758-766 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba-Aissa F., Raeymaekers L., Wuytack F., Dode L., Casteels R. (1998a). Distribution and isoform diversity of the organellar Ca2+ pumps in the brain. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 33, 199-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba-Aissa F., Van den Bosch L., Wuytack F., Raeymaekers L., Casteels R. (1998b). Regulation of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) 2 gene transcript in neuronal cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 55, 92-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S., Papa F. R., Walter P. (2006). Intracellular signaling by the unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 487-508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S. (1994). Darier's disease – the clinical features and pathogenesis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 19, 193-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo A. K., Ortis F., Storling J., Feng Y. M., Rasschaert J., Tonnesen M., Van Eylen F., Mandrup-Poulsen T., Herchuelz A., Eizirik D. L. (2005). Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 54, 452-461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen C., Pedersen P. S., Treiman M. (2000). The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2b is an endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible protein. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22363-22372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dally S., Bredoux R., Corvazier E., Andersen J. P., Clausen J. D., Dode L., Fanchaouy M., Gelebart P., Monceau V., Del Monte F., et al. (2006). Ca2+-ATPases in non-failing and failing heart: evidence for a novel cardiac sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2 isoform (SERCA2c). Biochem. J. 395, 249-258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode L., Andersen J. P., Leslie N., Dhitavat J., Vilsen B., Hovnanian A. (2003). Dissection of the functional differences between sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) 1 and 2 isoforms and characterization of Darier disease (SERCA2) mutants by steady-state and transient kinetic analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47877-47889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foggia L., Aronchik I., Aberg K., Brown B., Hovnanian A., Mauro T. M. (2006). Activity of the hSPCA1 Golgi Ca2+ pump is essential for Ca2+-mediated Ca2+ response and cell viability in Darier disease. J. Cell Sci. 119, 671-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godic A. (2004). Darier disease: a guide to the physician. J. Med. 35, 5-17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Bonifas J. M., Beech J., Bench G., Shigihara T., Ogawa H., Ikeda S., Mauro T., Epstein E. H., Jr. (2000). Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat. Genet. 24, 61-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen N. J., Lyons I., Hoogendoorn B., Burge S., Kwok P. Y., O'Donovan M. C., Craddock N., Owen M. J. (1999). ATP2A2 mutations in Darier's disease and their relationship to neuropsychiatric phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1631-1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. Y., Wek R. C. (2005). Phosphorylation of the alpha-subunit of the eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF2alpha) reduces protein synthesis and enhances apoptosis in response to proteasome inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14189-14202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., Kopito R. R. (1998). Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883-1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen P. T., Myllyla R. M., Hagg P. M., Tuukkanen J., Koivunen J., Peltonen S., Oikarinen A., Korkiamaki T., Peltonen J. (2005). Keratinocytes cultured from patients with Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease display distinct patterns of calcium regulation. Br. J. Dermatol. 153, 113-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ge M., Ciani L., Kuriakose G., Westover E. J., Dura M., Covey D. F., Freed J. H., Maxfield F. R., Lytton J., et al. (2004). Enrichment of endoplasmic reticulum with cholesterol inhibits sarcoplasmic-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase-2b activity in parallel with increased order of membrane lipids: implications for depletion of endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores and apoptosis in cholesterol-loaded macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37030-37039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. H., Boivin G. P., Prasad V., Periasamy M., Shull G. E. (2001). Squamous cell tumors in mice heterozygous for a null allele of Atp2a2, encoding the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 Ca2+ pump. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26737-26740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang Y., Wu C., Liu Y., Zheng P. (2009). Deletions and missense mutations of EPM2A exacerbate unfolded protein response and apoptosis of neuronal cells induced by endoplasm reticulum stress. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 2622-2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton J., Westlin M., Burk S. E., Shull G. E., MacLennan D. H. (1992). Functional comparisons between isoforms of the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum family of calcium pumps. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 14483-14489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller E. J., Caldelari R., Kolly C., Williamson L., Baumann D., Richard G., Jensen P., Girling P., Delprincipe F., Wyder M., et al. (2006). Consequences of depleted SERCA2-gated calcium stores in the skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 721-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okunade G. W., Miller M. L., Azhar M., Andringa A., Sanford L. P., Doetschman T., Prasad V., Shull G. E. (2007). Loss of the Atp2c1 secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase (SPCA1) in mice causes Golgi stress, apoptosis, and midgestational death in homozygous embryos and squamous cell tumors in adult heterozygotes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26517-26527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzmann J. A., Li L., Chin L. S. (2008). Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 47-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onozuka T., Sawamura D., Goto M., Yokota K., Shimizu H. (2006). Possible role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of Darier's disease. J. Dermatol. Sci. 41, 217-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. T., Churn S. B., Kochan L. D., DeLorenzo R. J. (2000). Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus causes N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent inhibition of microsomal Mg2+/Ca2+ ATPase-mediated Ca2+ uptake. J. Neurochem. 75, 1209-1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringpfeil F., Raus A., DiGiovanna J. J., Korge B., Harth W., Mazzanti C., Uitto J., Bale S. J., Richard G. (2001). Darier disease – novel mutations in ATP2A2 and genotype-phenotype correlation. Exp. Dermatol. 10, 19-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Perez V. L., Carter S. A., Healy E., Todd C., Rees J. L., Steijlen P. M., Carmichael A. J., Lewis H. M., Hohl D., Itin P., et al. (1999). ATP2A2 mutations in Darier's disease: variant cutaneous phenotypes are associated with missense mutations, but neuropsychiatric features are independent of mutation class. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1621-1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski D. T., Kaufman R. J. (2004). A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 20-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuntabhai A., Ruiz-Perez V., Carter S., Jacobsen N., Burge S., Monk S., Smith M., Munro C. S., O'Donovan M., Craddock N., et al. (1999). Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier disease. Nat. Genet. 21, 271-277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Briggs F. N. (1974). Estimating the functional capabilities of sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiac muscle. Calcium binding. Circ. Res. 34, 531-540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman M., Caspersen C., Christensen S. B. (1998). A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 131-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verboomen H., Wuytack F., Van den Bosch L., Mertens L., Casteels R. (1994). The functional importance of the extreme C-terminal tail in the gene 2 organellar Ca2+-transport ATPase (SERCA2a/b). Biochem. J. 303, 979-984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]