Abstract

Behavioral Couples Therapy (BCT) is designed for married or cohabiting individuals seeking help for alcoholism or drug abuse. BCT sees the substance abusing patient together with the spouse or live-in partner. Its purposes are to build support for abstinence and to improve relationship functioning. BCT promotes abstinence with a “recovery contract” that involves both members of the couple in a daily ritual to reward abstinence. BCT improves the relationship with techniques for increasing positive activities and improving communication. BCT also fits well with 12-step or other self-help groups, individual or group substance abuse counseling, and recovery medications. Research shows that BCT produces greater abstinence and better relationship functioning than typical individual-based treatment and reduces social costs, domestic violence, and emotional problems of the couple’s children. Thus research evidence supports wider use of BCT. We hope this article and new print and web-based resources on how to implement BCT will lead to increased use of BCT to the benefit of substance abusing patients and their families.

Keywords: Behavioral Couples Therapy, alcoholism, drug abuse

Overview

The purpose of Behavioral Couples Therapy (BCT) is to build support for abstinence and to improve relationship functioning among married or cohabiting individuals seeking help for alcoholism or drug abuse. BCT sees the substance abusing patient with the spouse or live-in partner to arrange a daily “Recovery Contract” in which the patient states his or her intent not to drink or use drugs and the spouse expresses support for the patient’s efforts to stay abstinent. For patients taking a recovery-related medication (e.g., disulfiram, naltrexone), daily medication ingestion witnessed and verbally reinforced by the spouse also is part of the contract. Self-help meetings and drug urine screens are part of the contract for most patients. BCT also increases positive activities and teaches communication skills.

Research shows that BCT produces greater abstinence and better relationship functioning than typical individual-based treatment and reduces social costs, domestic violence, and emotional problems of the couple’s children. Despite the strong evidence base supporting BCT, it is rarely used in substance abuse treatment programs. Low use of BCT may stem from the recency of studies on BCT, many of which were published in the past 15 years. Further, BCT clinical methods and the research supporting BCT have not been widely disseminated. This article will acquaint substance abuse treatment program administrators and clinicians with BCT. Hopefully this will lead to increased use of BCT to the benefit of substance abusing patients and their families. For a more detailed consideration of the material covered in this article, see O’Farrell and Fals-Stewart (2006).

Clinical Procedures for Behavrioal Couples Therapy

BCT works directly to increase relationship factors conducive to abstinence. A behavioral approach assumes that family members can reward abstinence -- and that alcoholic and drug abusing patients from happier, more cohesive relationships with better communication have a lower risk of relapse. The substance abusing patient and the spouse, are seen together in BCT, typically for 12-20 weekly outpatient couple sessions over a 3-6 month period. BCT can be an adjunct to individual counseling or it can be the only substance abuse counseling the patient receives. Generally couples are married or cohabiting for at least a year, without current psychosis, and one member of the couple has a current problem with alcoholism and/or drug abuse. The couple starts BCT soon after the substance abuser seeks help. BCT can start immediately after detoxification or a short-term intensive rehab program or when the substance abuser seeks outpatient counseling. The remainder of this section on clinical procedures for BCT is written in the form of instructions to a counselor who wants to use BCT. Table 1 notes key aspects of BCT.

Table 1. BCT for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse.

|

To engage the spouse and the patient together in BCT, first get the substance abusing patient’s permission to contact the spouse. Then talk directly to the spouse to invite him or her for an initial BCT couple session. The initial BCT session involves assessing substance abuse and relationship functioning, and then gaining commitment to and starting BCT. You start first with substance-focused interventions that continue throughout BCT to promote abstinence. When abstinence and attendance at BCT sessions have stabilized for a few weeks, you add relationship-focused interventions to increase positive activities and teach communication. These specific BCT interventions are described in detail next.

Substance-Focused Interventions in BCT

Daily Recovery Contract

You can arrange what we call a daily Recovery Contract. The first part of the contract is the “trust discussion”. In it, the patient states his or her intent not to drink or use drugs that day (in the tradition of one day at a time) and the spouse expresses support for the patient’s efforts to stay abstinent. For patients taking a recovery-related medication (e.g., disulfiram, naltrexone), daily medication ingestion witnessed and verbally reinforced by the spouse also is part of the contract. The spouse records the performance of the daily contract on a calendar you give him or her. Both partners agree not to discuss past drinking or fears about future drinking at home to prevent substance-related conflicts which can trigger relapse, reserving these discussions for the therapy sessions. At the start of each BCT session, review the Recovery Contract calendar to see how well each spouse has done their part. Have the couple practice their trust discussion (and medication taking if applicable) in each session to highlight its importance and to let you see how they do it. Twelve-step or other self-help meetings are a routine part of BCT for all patients who are willing. Urine drug screens taken at each BCT session are included in BCT for all patients with a current drug problem. If the Recovery Contract includes 12-step meetings or urine drug screens, these are also marked on the calendar and reviewed. The calendar provides an ongoing record of progress that you reward verbally at each session. Table 2 summarizes the components of the Recovery Contract.

Table 2. Components of Recovery Contract.

|

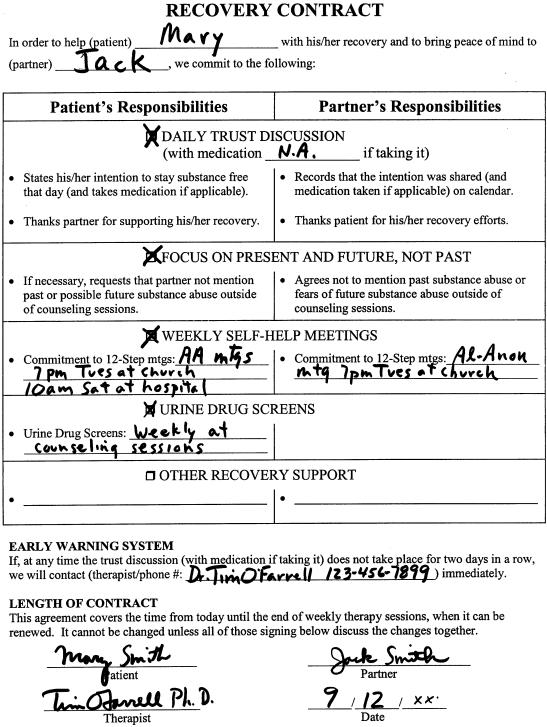

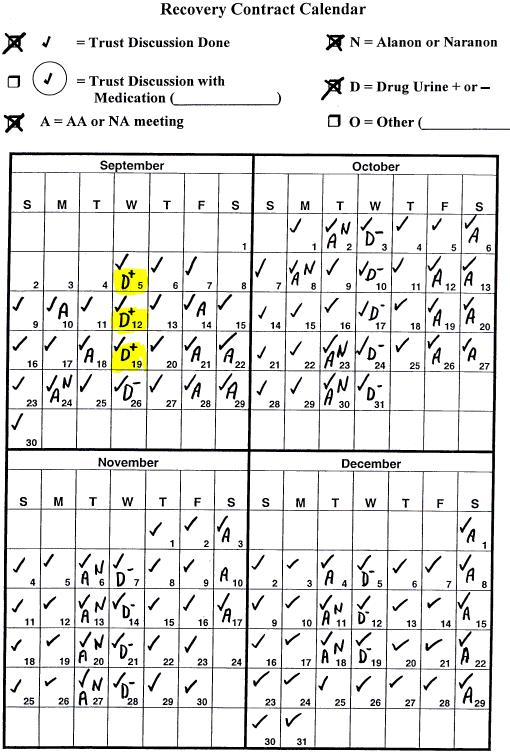

Recovery Contract Case Example #1

Figure 1 presents the Recovery Contract and calendar for Mary Smith and her husband Jack. Mary was a 34-year old teacher’s aide in an elementary school who had a serious drinking problem and also smoked marijuana daily. She was admitted to a detoxification unit at a community hospital after being caught drinking at work and being suspended from her job. Her husband Jack worked in a local warehouse and was a light drinker with no drug involvement. Mary and Jack had been married 8 years, and Jack was considering leaving the marriage, when the staff at the detoxification unit referred them to the BCT program.

Figure 1.

Recovery Contract and calendar for Mary and Jack.

The therapist developed a Recovery Contract in which Mary agreed to a daily “trust discussion” in which she stated to Jack her intent to stay “clean and sober” for the next 24 hours and Jack thanked her for her commitment to sobriety. The couple practiced this ritual in the therapist’s office until it felt comfortable, and then also performed the discussion at each weekly therapy session on Wednesday evening. As the calendar in Figure 1 shows, they did this part of the contract nearly every day, missing only on an occasional Saturday because their schedule was different that day and sometimes they forgot. Mary agreed to at least 2 AA meetings each week and actually attended 3 meetings per week for the first two months. Jack was pleased to see Mary not drinking and going to AA. However, he was upset that weekly drug urine screens were positive for marijuana for the first few weeks, taking this as evidence that his wife was still smoking marijuana even though she denied it. The therapist explained that marijuana could stay in the system for some time particularly in someone who had been a daily pot smoker. The therapist suggested Jack go to Al-Anon to help him deal with his distress over his wife’s suspected drug use. After a few weeks, the drug screens were negative for marijuana and stayed that way lending further credence to Mary’s daily statement of intent. Jack found Al-Anon helpful and the couple added to their contract that one night a week they would go together to a local church where Mary could attend an AA meeting and Jack an Al-Anon meeting.

Recovery Contract with a Recovery Medication

A medication to aid recovery is often part of BCT. Medications include Naltrexone for heroin-addicted or alcoholic patients and Antabuse (disulfiram) for alcoholic patients. Antabuse is a drug that produces extreme nausea and sickness when the person taking it drinks. As such it is an option for drinkers with a goal of abstinence. Traditional Antabuse therapy often is not effective because the drinker stops taking it. The Antabuse Contract, also part of the Community Reinforcement Approach, significantly improves compliance in taking the medication and increases abstinence rates. In the Antabuse Contract, the drinker agrees to take Antabuse each day while the spouse observes. The spouse, in turn, agrees to positively reinforce the drinker for taking the Antabuse, to record the observation on a calendar you provide them, and not to mention past drinking or any fears about future drinking. Each spouse should view the agreement as a cooperative method for rebuilding lost trust and not as a coercive checking-up operation. Before negotiating such a contract, make sure that the drinker is willing and medically cleared to take Antabuse and that both the drinker and spouse have been fully informed and educated about the effects of the drug. This is done by the prescribing physician but double check the couple’s level of understanding about it.

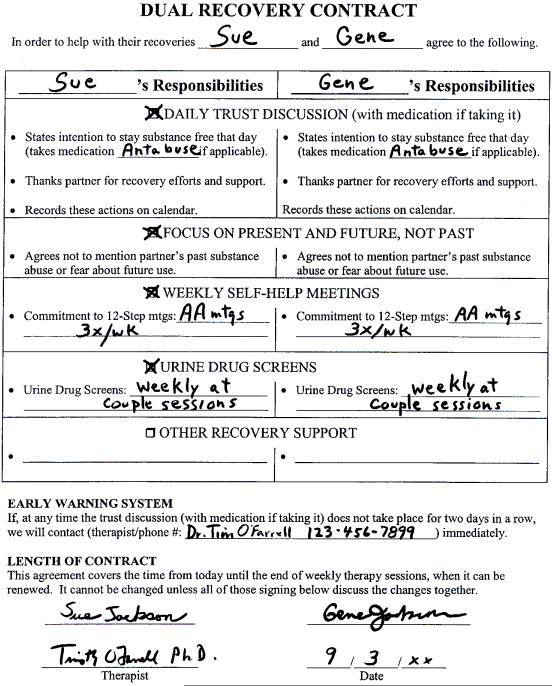

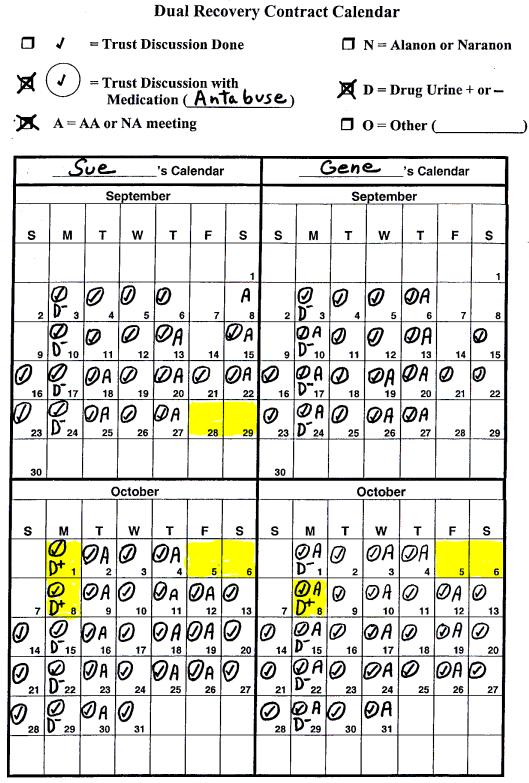

Recovery Contract Case Example #2

If both members of a couple have a current substance problem and both want abstinence, then BCT often is workable. This is the case of Sue and Gene -- a dual problem couple. Sue came to BCT after detox for heavy daily drinking plus cocaine and marijuana 3-4 times per week. Gene had similar problems but did not need detox. Both wanted to “quit for good” to get their 3 school age children back. Sue’s parents were given temporary custody when Gene was arrested for drunk driving. Sue, also intoxicated, and the kids were in the car. Sue and Gene had 6 months of weekly BCT. Their “dual recovery contract” shown in Figure 2 had (1) a daily trust discussion, (2) taking Antabuse daily together, (3) 3 AA meetings per week, and (4) weekly urine screens.

Figure 2.

Recovery Contract and calendar for Sue and Gene.

About 5 weeks after starting BCT, Sue used cocaine on Friday night when she went to the local bar with a girlfriend. At the next BCT session her urine was positive for cocaine. The following Friday found them both in the bar. They planned to just socialize, but when cocaine was offered they didn’t refuse, but just did 1 line each. The next night they went to the bar again and each used multiple lines of cocaine. This relapse was a turning point. They got more committed to their recovery. They planned things to do Friday and Saturday nights, starting with an AA meeting together on Friday night. Each got a sponsor and some sober friends.

After weekly BCT, they had quarterly checkups for 2 more years. They re-gained custody of their children and stayed abstinent except for a few isolated days for Gene and a 5-day relapse for Sue, which led to a few crisis sessions with the BCT counselor to help them get back on track.

Other Support for Abstinence

Reviewing urges to drink or use drugs experienced in the past week is part of each BCT session. This includes thoughts and temptations that are less intense than an urge or a craving. Discussing situations, thoughts and feeling associated with urges helps identify potential triggers or cues for alcohol or drug use. It can help alert you to the possible risk of a relapse. It also identifies successful coping strategies (e.g., distraction, calling a sponsor) the patient used to resist an urge, and it builds confidence for the future.

Crisis intervention for substance use is an important part of BCT. Drinking or drug use episodes occur during BCT as with any other treatment. BCT works best if you intervene before the substance use goes on for too long a period. In an early BCT session, negotiate an agreement that either member of the couple should call you if substance use occurs or if they fear it is imminent. Once substance use has occurred, try to get it stopped and to see the couple as soon as possible to use the relapse as a learning experience. At the couple session, you must be extremely active in defusing hostile or depressive reactions to the substance use. Stress that drinking or drug use does not constitute total failure, that inconsistent progress is the rule rather than the exception. Help the couple decide what they need to do to feel sure that the substance use is over and will not continue in the coming week (e.g., restarting recovery medication, going to AA and Al-Anon together, reinstituting a daily Recovery Contract, entering a detoxification unit). Finally, try to help the couple identify what trigger led up to the relapse and generate alternative solutions other than substance use for similar future situations.

Relationship-Focused Interventions in BCT

Once the Recovery Contract is going smoothly, the substance abuser has been abstinent and the couple has been keeping scheduled appointments for a few weeks, you can start to focus on improving couple and family relationships. Family members often experience resentment about past substance abuse and fear and distrust about the possible return of substance abuse in the future. The substance abuser often experiences guilt and a desire for recognition of current improved behavior. These feelings experienced by the substance abuser and the family often lead to an atmosphere of tension and unhappiness in couple and family relationships. There are problems caused by substance use (e.g. bills, legal charges, embarrassing incidents) that still need to be resolved. There is often a backlog of other unresolved couple and family problems that the substance use obscured. The couple frequently lacks the mutual positive feelings and communication skills needed to resolve these problems. As a result, many marriages and families are dissolved during the first 1 or 2 years of the substance abuser’s recovery. In other cases, couple and family conflicts trigger relapse and a return to substance abuse. Even in cases where the substance abuser has a basically sound marriage and family life when he or she is not abusing substances, the initiation of abstinence can produce temporary tension and role readjustment and provide the opportunity for stabilizing and enriching couple and family relationships. For these reasons, many substance abusing patients can benefit from assistance to improve their couple and family relationships.

Two major goals of interventions focused on the substance abuser’s couple relationship are (a) to increase positive feeling, goodwill, and commitment to the relationship; and (b) to teach communication skills to resolve conflicts, problems, and desires for change. The general sequence in teaching couples and families skills to increase positive activities and improve communication is (a) therapist instruction and modeling, (b) the couple practicing under your supervision, (c) assignment for homework, and (d) review of homework with further practice. Table 3 summarizes relationship-focused interventions in BCT.

Table 3. Relationship-Focused Interventions in BCT.

|

Increasing Positive Activities

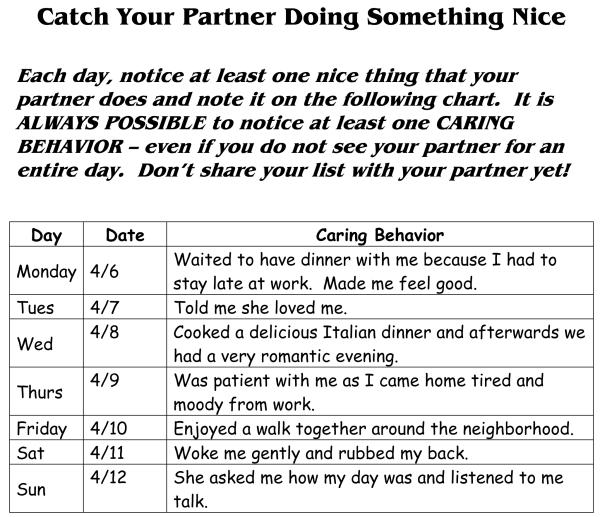

Catch Your Partner Doing Something Nice

A series of procedures can increase a couple’s awareness of benefits from the relationship and the frequency with which spouses notice, acknowledge, and initiate pleasing or caring behaviors on a daily basis. Tell the couple that caring behaviors are “behaviors showing that you care for the other person,” and assign homework called “Catch Your Partner Doing Something Nice” to assist couples in noticing daily caring behaviors. This requires each spouse to record one caring behavior performed by the partner each day on sheets you provide them (see Figure 3). The couple reads the caring behaviors recorded during the previous week at the subsequent session. Then you model acknowledging caring behaviors (“I liked it when you ______________. It made me feel _____________.”), noting the importance of eye contact; a smile; a sincere, pleasant tone of voice; and only positive feelings. Each spouse then practices acknowledging caring behaviors from his or her daily list for the previous week.

Figure 3.

Sample “Catch Your Partner Doing Something Nice” sheet.

After the couple practices the new behavior in the therapy session, assign for homework a 2-5 minute daily communication session at home in which each partner acknowledges one pleasing behavior noticed that day. These daily brief acknowledgments often are done at the same time as the “trust discussion” that is part of the Recovery Contract. As couples begin to notice and acknowledge daily caring behaviors, each partner beings initiating more caring behaviors. Often the weekly reports of daily caring behaviors show that one or both spouses are fulfilling requests for desired change voiced before the therapy. In addition, many couples report that the 2-5 minute communication sessions result in more extensive conversations.

Planning Shared Rewarding Activities

Many substance abusers’ families stop shared recreational and leisure activities due to strained relationships and embarrassing substance-related incidents. Reversing this trend is important because participation by the couple and family in social and recreational activities improves substance abuse treatment outcomes (Moos, Finney & Cronkite, 1990). Planning and engaging in shared rewarding activities can be started by simply having each spouse make a separate list of possible activities. Each activity must involve both spouses, either by themselves or with their children or other adults and can be at or away from home. Before giving the couple homework of planning a shared activity, model planning an activity to illustrate solutions to common pitfalls (e.g., waiting until the last minute so that necessary preparations cannot be made, getting sidetracked on trivial practical arrangements). Finally, instruct the couple to refrain from discussing problems or conflicts during their planned activity.

Caring Day

A final assignment is that each partner give the other a “Caring Day” during the coming week by performing special acts to show caring for the spouse. Encourage each partner to take risks and to act lovingly toward the spouse rather than wait for the other to make the first move. Finally, remind spouses that at the start of therapy they agreed to act differently (e.g., more lovingly) and then assess changes in feelings, rather than wait to feel more positively toward their partner before instituting changes in their own behavior.

Teaching Communication Skills

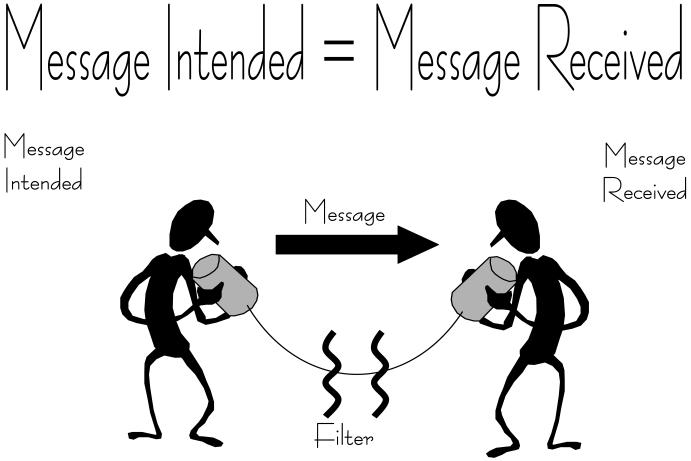

We generally begin our work on training in communication skills by defining effective communication as “message intended (by speaker) equals message received (by listener)” and emphasizing the need to learn both “listening” and “speaking” skills. The chart presented in Figure 4 helps expand this definition further including factors (e.g., “filters”) in each person that can impede communication.

Figure 4.

Good communication defined.

Teaching couples communication skills of listening and speaking and how to use planned communication sessions are essential prerequisites for negotiating desired behavior changes. Start this training with non-problem areas that are positive or neutral and move to problem areas and emotionally charged issues only after each skill has been practiced on easier topics.

Listening Skills

Good listening helps each spouse to feel understood and supported and to slow down couple interactions to prevent quick escalation of aversive exchanges. Instruct spouses to repeat both the words and the feelings of the speaker’s message and to check to see if the message they received was the message intended by their partner (“What I heard you say was …. Is that right?”). When the listener has understood the speaker’s message, roles change and the first listener then speaks. Teaching a partner to communicate support and understanding by summarizing the spouse’s message and checking the accuracy of the received message before stating his or her own position is often a major accomplishment that has to be achieved gradually. A partner’s failure to separate understanding the spouse’s position from agreement with it often is an obstacle that must be overcome.

Expressing Feelings Directly

Expressing both positive and negative feelings directly is an alternative to the blaming, hostile, and indirect responsibility-avoiding communication behaviors that characterize many substance abusers’ relationships. Emphasize that when the speaker expresses feelings directly, there is a greater chance that he or she will be heard because the speaker says these are his or her feelings, his or her point of view, and not some objective fact about the other person. The speaker takes responsibility for his or her own feelings and does not blame the other person for how he or she feels. This reduces listener defensiveness and makes it easier for the listener to receive the intended message. Present examples of differences between direct expressions of feelings and indirect and ineffective or hurtful expressions. The use of statements beginning with “I” rather than “you” is emphasized. After presenting the rationale and instructions, model correct and incorrect ways of expressing feelings and elicit the couple’s reactions to these modeled scenes. Then have the couple role-play a communication session in which spouses take turns being speaker and listener, with the speaker expressing feelings directly and the listener using the listening response. During this role-playing, coach the couple as they practice reflecting the direct expressions of feelings. Assign for homework similar communication sessions, 10 to 15 minutes each three to four times weekly. Subsequent therapy sessions involve more practice with role-playing, both during the sessions and for homework. Increase in difficulty each week the topics on which the couple practices.

Communication Sessions

These are planned, structured discussions in which spouses talk privately, face-to-face, without distractions, and with each spouse taking turns expressing his or her point of view without interruptions. Communication sessions can be introduced for 2-5 minutes daily when couples first practice acknowledging caring behaviors. In later weeks when the couple discusses current relationship problems or concerns, communication sessions typically are assigned for 10-to 15-minutes three to four times a week. Discuss with the couple the time and place that they plan to have their assigned communication practice sessions. Assess the success of this plan at the next session, and suggest any needed changes. Just establishing a communication session as a method for discussing feelings, events, and problems can be very helpful for many couples. Encourage couples to ask each other for a communication session when they want to discuss an issue or problem, keeping in mind the ground rules of behavior that characterize such a session.

Negotiating for Requests

Many changes that spouses desire from their partners can be achieved through the caring behaviors, rewarding activities, and communication skills that have already been mentioned. However, deeper, emotion-laden conflicts that have caused considerable hostility and arguments for years are more resistant to change. Learning to make positive specific requests and to negotiate and compromise can lead to agreements to resolve such issues.

Positive specific requests are an alternative to the all-too-frequent practice of couples complaining in vague and unclear terms and trying to coerce, browbeat, and force the other partner to change. For homework each partner lists at least five requests. Negotiation and compromise comes next. Spouses share their lists of requests, starting with the most specific and positive items. Give feedback on the requests presented and help rewrite items as needed. Then explain that negotiating and compromising can help couples reach an agreement in which each partner will do one thing requested by the other. After giving instructions and examples, coach a couple while they have a communication session in which requests are made in a positive specific form, heard by each partner, and translated into a mutually satisfactory, realistic agreement for the upcoming week. Finally, record the agreement on a homework sheet that the couple knows you will review with them during the next session. Such agreements can be a major focus of a number of BCT sessions.

Maintenance and Relapse Prevention

We suggest using three general methods to promote long-term maintenance of the changes in substance problems made through BCT. First, plan maintenance prior to the termination of the weekly treatment phase. This involves helping the couple complete a Continuing Recovery Plan that specifies which behaviors from the previous BCT sessions they wish to continue (e.g., daily trust discussion, AA meetings, shared rewarding activities, communication sessions). Second, anticipate high-risk situations for relapse that may occur after weekly treatment ends. Discuss and rehearse possible coping strategies that the substance abuser and spouse can use to prevent relapse when confronted with such situations. Third, discuss and rehearse how to cope with a relapse if it occurs. A specific relapse plan, written and rehearsed prior to ending weekly treatment, can be particularly useful. Early intervention at the beginning of a relapse episode is essential: impress the couple with this point. Often, individuals wait until the substance use has reached dangerous levels again before acting. By then, much additional damage has been done to couple and family relationships and to other aspects of the substance abuser’s life.

We suggest continued contact with the couple via planned in-person and telephone follow-up sessions, at regular and then gradually increasing intervals, preferably for 3 to 5 years after a stable pattern of recovery has been achieved. Use this ongoing contact to monitor progress, to assess compliance with the Continuing Recovery Plan, and to evaluate the need for additional therapy sessions. You must take responsibility for scheduling and reminding the couple of follow-up sessions and for placing agreed-upon phone calls so that continued contact can be maintained successfully. Tell couples the reason for continued contact is that substance abuse is a chronic health problem that requires active, aggressive, ongoing monitoring to prevent or to quickly treat relapses for at least 5 years after an initial stable pattern of recovery has been established. The follow-up contact also provides the opportunity to deal with couple and family issues that appear after a period of recovery.

Contraindications for BCT

A few contraindications for BCT should be considered. First, couples in which there is a court-issued restraining order for the spouses not to have contact with each other should not be seen together in therapy until the restraining order is lifted or modified to allow contact in counseling.

Second, couples are excluded from BCT if very severe domestic violence (defined as resulting in injury requiring medical attention or hospitalization) has occurred in the past two years or if one or both members of the couple fear that taking part in couples treatment may stimulate violence (Fals-Stewart & Kennedy, 2005; O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006). Although domestic violence is quite common among substance abuse patients, most of this violence is not so severe that it precludes BCT. In our experience fewer than 2% of couples seeking BCT are excluded from being treated in BCT due to very severe violence or fears of couples therapy. The best plan in the vast majority of cases is to address the violence in BCT sessions by teaching a commitment to nonviolence, communication skills to reduce hostile conflicts, and coping skills to minimize conflict if the substance abuser relapses (for details see O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006; O’Farrell & Murphy, 2002). Research reviewed below shows that violence is substantially reduced after BCT and virtually eliminated for patients who stay abstinent.

Finally, if the spouse also has a current alcohol or drug problem, BCT may not be effective. In the past, we have often taken the stance that if both members of a couple have a substance use problem, then we will not treat them together unless one member of the couple has at least 90 days abstinence. However, in a recent project we successfully treated couples in which both the male and female partner had a current alcoholism problem (Schumm, O’Farrell, Murphy & Fals-Stewart, 2006). If both members of the couple want to stop drinking or if this mutual decision to change can be reached in the first few sessions, then BCT may be workable.

Effectiveness of Behavioral Couples Therapy

BCT produced better outcomes than more typical individual-based treatment for married or cohabiting alcoholic and drug-abusing patients in a meta-analysis of 12 controlled studies that showed a medium effect size favoring BCT over individual treatment (Powers, Vedel & Emmelkamp, 2008). This medium effect size favoring BCT over individual treatment is 10 times greater than that observed for aspirin in preventing heart attacks, an effect considered important in medical research (Rosenthal, 1991). BCT is the family therapy method with the strongest research support for its effectiveness in substance abuse (Epstein & McCrady, 1998). Table 4 summarizes results of studies on BCT that are covered below.

Table 4. Studies of BCT Show.

|

Primary Clinical Outcomes: Abstinence and Relationship Functioning

A series of studies have compared substance abuse and relationship outcomes for substance abusing patients treated with BCT or individual counseling. Outcomes have been measured at 6-months follow-up in earlier studies and at 12-24 months after treatment in more recent studies. The studies show a fairly consistent pattern of more abstinence and fewer substance-related problems, happier relationships, and lower risk of couple separation and divorce for substance abusing patients who receive BCT than for patients who receive only more typical individual-based treatment. These results come from studies with mostly male alcoholic (Azrin, Sisson, Meyers & Godley, 1982; Bowers & Al-Rehda, 1990; Chick et al., 1992; Hedberg & Campbell, 1974; Fals-Stewart, Klosterman, Yates, O’Farrell & Birchler, 2005; Fals-Stewart & O’Farrell, 2002; Kelley & Fals-Stewart, 2002; McCrady, Stout, Noel, Abrams & Nelson, 1991; O’Farrell, Cutter, Choquette, Floyd & Bayog, 1992) and drug abusing (Fals-Stewart, Birchler & O’Farrell, 1996; Fals-Stewart & O’Farrell, 2003; Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell & Birchler, 2001a, 2001b; Kelley & Fals-Stewart, 2002) patients and also with female alcoholic (Fals-Stewart, Birchler & Kelley, 2006) and drug abusing patients (Winters, Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, Birchler & Kelley, 2002).

Social Cost Outcomes and Benefit-to-Cost Ratio

Three studies (2 in alcoholism and 1 in drug abuse) have examined social cost outcomes after BCT (O’Farrell et al, 1996a, 1996b; Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell & Birchler, 1997). These social costs included costs for substance abuse-related health care, criminal justice system use for substance-related crimes, and income from illegal sources and public assistance. The average social costs per case decreased substantially in the 1-2 years after as compared to the year before BCT, with cost savings averaging $5,000 - $6,500 per case. Reduced social costs after BCT saved more than 5 times the cost of delivering BCT, producing a benefit-to-cost ratio greater than 5:1. Thus, for every dollar spent in delivering BCT, 5 dollars in social costs are saved. In addition, BCT was more cost-effective when compared with individual treatment for drug abuse (Fals-Stewart et al, 1997) and when compared with interactional couples therapy for alcoholism (O’Farrell et al, 1996b).

Domestic Violence Outcomes

A recent study (O’Farrell, Murphy, Stephan, Fals-Stewart & Murphy, 2004) examined male-to-female partner violence before and after BCT for 303 married or cohabiting male alcoholic patients. There also was a demographically matched comparison sample of couples without alcohol problems. In the year before BCT, 60% of alcoholic patients had been violent toward their female partner, five times the comparison sample rate of 12%. In the year after BCT, violence decreased significantly to 24% of the alcoholic sample but remained higher than the comparison group. Among remitted alcoholics after BCT, violence prevalence of 12% was identical to the comparison sample and less than half the rate among relapsed patients (30%). Results for the second year after BCT were similar to the first year. An earlier study (O’Farrell & Murphy, 1995) found nearly identical results. Thus, these 2 studies showed that male-to-female violence was significantly reduced in the first and second year after BCT and that it was nearly eliminated with abstinence.

Two recent studies showed that BCT reduced partner violence and couple conflicts better than individual treatment. Among male drug abusing patients, while nearly half of the couples reported male-to-female violence in the year before treatment, the number reporting violence in the year after treatment was significantly lower for BCT (17%) than for individual treatment (42%) (Fals-Stewart, Kashdan, O’Farrell, Birchler & Kelley, 2002). Among male alcoholic patients, those who participated in BCT reported less frequent use of maladaptive responses to conflict (e.g., yelling, name-calling, threatening to hit, hitting) during treatment than those who received individual treatment (Birchler & Fals-Stewart, 2001). These results suggest that in BCT couples do learn to handle their conflicts with less hostility and aggression.

Impact of BCT on the Children of Couples Undergoing BCT

Kelley and Fals-Stewart (2002) conducted 2 studies (1 in alcoholism, 1 in drug abuse) to find out whether BCT for a substance abusing parent, with its demonstrated reductions in domestic violence and reduced risk for family breakup, also has beneficial effects for the children in the family. Results were the same for children of male alcoholic and male drug abusing fathers. BCT improved children’s functioning in the year after the parents’ treatment more than did individual-based treatment or couple psychoeducation. Only BCT showed reduction in the number of children with clinically significant impairment.

Integrating BCT with Recovery Related Medication

BCT has been used to increase compliance with a recovery-related medication. Fals-Stewart and O’Farrell (2003) compared BCT with individual treatment for male opioid-addicted patients taking naltrexone. BCT patients, compared with their individually treated counterparts, had better naltrexone compliance, greater abstinence, and fewer substance-related problems. Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell and Martin (2002) found that BCT produced better compliance with HIV medications among HIV-positive drug abusers in an outpatient drug abuse treatment program than did treatment as usual. BCT also has improved compliance with pharmacotherapy in studies of disulfiram for alcoholic patients [e.g., Azrin et al, 1982; Chick et al, 1992; O’Farrell et al, 1992) and in a pilot study of naltrexone with alcoholics (Fals-Stewart & O’Farrell, 2002).

BCT with Family Members Other than Spouses

Most BCT studies have examined traditional couples. However, some recent studies have expanded BCT to include family members other than spouses. These studies have targeted increased medication compliance as just described. For example, in the study of BCT and naltrexone with opioid patients (Fals-Stewart & O’Farrell, 2003), family members taking part were spouses (66%), parents (25%), and siblings (9%). In the study of BCT and HIV medications among HIV-positive drug abusers (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell & Martin, 2002), significant others who took part were: a parent or sibling (67%), a homosexual (12%) or heterosexual (9%) partner, or a roommate (12%).

Needed Research

In terms of future directions, we do need more research on BCT, to replicate and extent the most recent advances, especially for women patients and broader family constellations. Research on BCT for couples in which both the male and female member have a current substance use problem is particularly needed because prior BCT studies have not addressed this difficult clinical challenge. Even more than additional research, we need technology transfer so that patients and their families can benefit from what we have already learned about BCT for alcoholism and drug abuse.

Summary and Conclusions

The purpose of Behavioral Couples Therapy is to build support for abstinence and to improve relationship functioning among married or cohabiting individuals seeking help for alcoholism or drug abuse. Research shows that BCT produces greater abstinence and better relationship functioning than typical individual-based treatment and reduces social costs, domestic violence, and emotional problems of the couple’s children. BCT fits well with 12-step or other self-help groups, individual or group substance abuse counseling, and recovery medications. Thus research evidence supports wider use of BCT. We hope this article will lead to increased use of BCT to the benefit of substance abusing patients and their families. In addition, the following resources are available for those interested in learning more about how to implement BCT:

A comprehensive counselor’s guide book to implementing BCT O’Farrell, T.J. & Fals-Stewart, W. (2006). Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. New York: Guilford Press.

A web-based distance learning course on BCT www.ireta.org/ireta_main/distance_learning.html

Acknowledgments

This article is adapted from a clinical guideline developed for the Behavioral Health Recovery Management project, a project of Fayette Companies, Peoria, IL and Chestnut Health Systems, Bloomington, IL, that was funded by the Illinois Department of Human Services’ Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse. This article also draws heavily from the book Behavioral Couples Therapy for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse, copyright 2006 by Guilford Press. This article also draws from “Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and other drug abuse”, 2008, Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 26, 195-219, copyright 2008 by Haworth Press. Material is used with permission from Fayette Companies, Guilford Press, and Haworth Press. Preparation of this article also was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA014700) and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Azrin NH, Sisson RW, Meyers R, Godley M. Alcoholism treatment by Disulfiram and community reinforcement therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1982;13:105–112. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(82)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchler GR, Fals-Stewart W. Use of behavioral couples therapy with alcoholic couples: Effects on maladaptive responses to conflict during treatment; Poster presented at the 35th Annual Convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Philadelphia, PA. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers TG, Al-Rehda MR. A comparison of outcome with group/marital and standard/individual therapies with alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51:301–309. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick J, Gough K, Falkowski W, Kershaw P, Hore B, Mehta B, Ritson B, Ropner R, Torley D. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;161:84–89. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, McCrady BS. Behavioral couples treatment of alcohol and drug use disorders: Current status and innovations. Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:689–711. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. Learning Sobriety Together: A randomized clinical trial examining behavioral couples therapy with female alcoholic patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:579–591. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral couples therapy for male substance-abusing patients: Effects on relationship adjustment and drug-using behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:959–972. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Kashdan TB, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for male-drug abusing patients and their partners: The effect on interpartner 22 violence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Kennedy C. Addressing intimate partner violence in substance-abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;29:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Klosterman K, Yates BT, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Brief relationship therapy for alcoholism: A randomized clinical trial examining clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:363–371. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral family counseling and naltrexone for male opioid dependent patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:432–442. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ. Behavioral couples therapy increases compliance with naltrexone among male alcoholic patients. Research institute on Addiction; Buffalo NY: 2002. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for male substance abusing patients: A cost outcomes analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:789–802. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Behavioral couples therapy for male methadone maintenance patients: Effects on drug-using behavior and relationship adjustment. Behavior Therapy. 2001a;32:391–411. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR. Use of abbreviated couples therapy in substance abuse. In J.V. Cordova (Chair). Approaches to Brief Couples Therapy: Application and Efficiency; Symposium conducted at the World Congress of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Vancouver, Canada. 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Martin J. Using behavioral family counseling to enhance HIV-medication compliance among HIV-infected male drug abusing patients; Paper presented at conference on “Treating Addictions in Special Populations,”; Binghamton, NY. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hedberg AG, Campbell L. A comparison of four behavioral treatments of alcoholism. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1974;5:251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Fals-Stewart W. Couples versus individual-based therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Effects on children’s psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:417–427. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady B, Stout R, Noel N, Abrams D, Nelson H. Comparative effectiveness of three types of spouse involved alcohol treatment: Outcomes 18 months after treatment. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1415–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Finney JW, Cronkite RC. Alcoholism treatment: Context, process, and outcome. Oxford University Press; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Choquette KA, Cutter HSG, Floyd FJ, Bayog RD, Brown ED, Lowe J, Chan A, Deneault P. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses of behavioral marital therapy as an addition to outpatient alcoholism treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1996a;8:145–166. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Choquette KA, Cutter HSG, Brown ED, Bayog R, McCourt W, Lowe J, Chan A, Deneault P. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses of behavioral marital therapy with and without relapse prevention sessions for alcoholics and their spouses. Behavior Therapy. 1996b;27:7–24. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Cutter HSG, Choquette KA, Floyd FJ, Bayog RD. Behavioral marital therapy for male alcoholics: Marital and drinking adjustment during the two years after treatment. Behavior Therapy. 1992;23:529–549. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM. Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse: Encountering the problem of domestic violence. In: Wekerle C, Wall AM, editors. The violence and addiction equation: Theoretical and clinical issues in substance abuse and relationship violence. Brunner-Routledge; New York NY: 2002. pp. 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM. Marital violence before and after alcoholism treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:256–262. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM, Stephen S, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Partner violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients: The role of treatment involvement and abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:202–217. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Vedel E, Emmelkamp PMG. Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol and drug use disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:952–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Revised edition Sage Publications; Newbury Park CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, O’Farrell TJ, Murphy M, Fals-Stewart W. Outcomes following behavioral couples therapy for couples in which both partners have alcoholism versus couples in which only one partner has alcoholism; Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Chicago. 2006, November. [Google Scholar]

- Winters J, Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. Behavioral couples therapy for female substance-abusing patients: Effects on substance use and relationship adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:344–355. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]