Abstract

Somatostatins have been shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of motor and affective disorders, as well as psychiatry disorders, including schizophrenia. We hypothesized that in addition to motor function, somatostatin may be involved in somatosensory gating and reward processes that have been shown to be dysregulated in schizophrenia. Accordingly, we evaluated the effects of intracerebroventricular administration of somatostatin-28 on spontaneous locomotor and exploratory behavior measured in a behavioral pattern monitor, sensorimotor gating, prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle reflex, and brain reward function (measured in a discrete trial intracranial self-stimulation procedure) in rats. Somatostatin-28 decreased spontaneous locomotor activity during the first 10 min of a 60 min testing session with no apparent changes in the exploratory activity of rats. The highest somatostatin-28 dose (10 μg/5 μl/side) induced PPI deficits with no effect on the acoustic startle response or startle response habituation. The somatostatin-induced PPI deficit was partially reversed by administration of SRA-880, a selective somatostatin 1 (sst1) receptor antagonist. Somatostatin-28 also induced elevations in brain reward thresholds, reflecting an anhedonic-like state. SRA-880 had no effect on brain reward function under baseline conditions. Altogether these findings suggest that somatostatin-28 modulates PPI and brain reward function but does not have a robust effect on spontaneous exploratory activity. Thus, increases in somatostatin transmission may represent one of the neurochemical mechanisms underlying anhedonia, one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and sensorimotor gating deficits associated with cognitive impairments in schizophrenia patients.

Keywords: sensorimotor gating, intracranial self-stimulation, reward thresholds, anhedonia, schizophrenia, SRA-880

1. Introduction

Somatostatins, also known as somatotropin-release inhibiting factors (SRIFs), have been shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of motor and affective disorders, as well as psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia (Brownstein et al., 1975; Vincent and Johansson, 1983; Rubinow et al., 1985; Rubinow, 1986; Vecsei and Widerlov, 1988a; Vecsei and Klivenyi, 1995; Epelbaum et al., 2009). Somatostatin and somatostatin receptors are widely distributed in the brain, including the cerebral and cingulate cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, and most structures of the limbic system and basal ganglia (Hoyer et al., 1995; Patel, 1999; Viollet et al., 2008) involved in motor, reward, and cognitive function. However, preclinical investigations of the role of endogenous brain somatostatin in reward and pre-cognitive sensory gating functions have been very limited due to the lack of selective non-peptide receptor agonists/antagonists for this peptide, very limited permeability of these peptides across the blood-brain barrier, and their fast degradation.

Somatostatins are peptides that exist in the brain in two main forms: somatostatin-14 (a tetradecapeptide) and somatostatin-28 (an amino-terminally extended octacosapeptide; (Hoyer et al., 1995; Hoyer et al., 2004). Somatostatin inhibits the release of a variety of pituitary hormones and plays a role as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (Patel, 1999; Bissette, 2001). Somatostatin (sst) receptors, which belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor family, are divided into five subtypes (sst1–sst5) and classified into two groups, SRIF1 (sst1, sst4) and SRIF2 (sst2, sst3, sst5) receptors (Hoyer et al., 1995; Patel, 1999; Fehlmann et al., 2000; Olias et al., 2004; Siehler et al., 2008; Viollet et al., 2008).

Somatostatin receptors in the striatum and other basal ganglia nuclei are involved in regulation of motor behavior. The striatum and the nucleus accumbens, two terminal areas of dopaminergic neurons, express both sst1 and sst2 receptors (Hoyer et al., 1995; Fehlmann et al., 2000). In the nucleus accumbens, the sst1 receptor is a somatostatin autoreceptor (Vasilaki et al., 2004; Thermos et al., 2006), whereas the sst2 receptor appears to be responsible for the actions of somatostatin on dopamine release and dopamine-mediated motor behaviors (Raynor et al., 1993; Thermos et al., 1996; Hathway et al., 1999; Viollet et al., 2000; Allen et al., 2003; Ikeda et al., 2009). Somatostatin can modulate locomotor activity by activating sst1, sst2 and sst4 receptors in the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata (Marazioti et al., 2005; Marazioti et al., 2008), and sst2 and sst4 receptors in the striatum (Santis et al., 2009). Although the effects of somatostatin on motor behavior have been extensively investigated, the reported findings in literature are not always in agreement. Specifically, the direction of the effects of somatostatins on locomotor activity depended on the dose, brain site of administration and somatostatin peptide (e.g., somatostatin-28, somatostatin-14) used, as well as the locomotor activity tests used (e.g., locomotor activity chamber, open field) (Vecsei et al., 1984; Vecsei and Widerlov, 1988b, 1990; Raynor et al., 1993; Tashev et al., 2001; Marazioti et al., 2005; Marazioti et al., 2008). Surprisingly little is known regarding the effects of somatostatins on quantitative measures of spontaneous locomotor and investigatory behavior. Therefore, one of the aims of the present studies was to assess the effects of intracerebvoventricular (i.c.v.) administration of somatostatin-28 on the spatial and temporal sequences of locomotor movements, investigatory holepokes, and rearings of rats using a behavioral pattern monitor allowing for sophisticated multivariate assessments of locomotor behavior (Geyer et al., 1986).

Disturbances in dopaminergic function may contribute to cognitive impairment and deficits in sensory gating observed in schizophrenia patients (Howes and Kapur, 2009). Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response (i.e., a reduction of a startle response elicited by an intense acoustic stimulus when it is immediately preceded by a stimulus of lower intensity) has been used as a measure of the loss of sensorimotor gating in patients with schizophrenia (Swerdlow and Geyer, 1998; Braff et al., 2001; Geyer et al., 2001). In rodents, PPI deficits have been induced with the administration of the direct and indirect dopamine receptor agonists apomorphine and amphetamine, respectively (Mansbach et al., 1988; Geyer et al., 2002), to model aspects of positive schizophrenia symptoms related to dysregulation of the dopaminergic system (Howes and Kapur, 2009). Administration of cysteamine, a sulfhydryl agent that decreases somatostatin levels (Sagar et al., 1982), impaired the development of the acoustic startle response in rats, indicating that somatostatin may influence the maturation of sensorimotor information processing (Kungel et al., 1996). Systemic administration of cysteamine (Feifel and Minor, 1997) or central administration of octreotide, an sst2/sst5 receptor selective octapeptide that pharmacologically mimics natural somatostatin, in the pontine reticular formation had no effect on baseline startle amplitude (Fendt et al., 1996). Interestingly, however, cysteamine reversed amphetamine-induced deficits in PPI, while having no effect on PPI when administered alone (Feifel and Minor, 1997), suggesting that somatostatin may play a role in the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. However, the effects of somatostatins on startle response and PPI have not been investigated.

In addition to cognitive function and sensorimotor gating, corticolimbic brain circuits involved in reward processes (Spanagel and Weiss, 1999; Koob and Volkow, 2010). Dysfunction in corticolimbic circuits may underlie reward deficits and anhedonia, one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In animals, the intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) procedure allows for the assessment of brain reward function (Markou and Koob, 1992). Elevations in thresholds are interpreted as a decrease in the reward value of the stimulation and are an operational measure of anhedonia (Markou and Kenny, 2002; Semenova and Markou, 2003; Paterson and Markou, 2007). Early studies reported that i.c.v. administration of somatostatin decreased self-stimulation rates measured in the rate-frequency self-stimulation procedure (Vecsei et al., 1982, 1983; Balazs et al., 1988), implicating somatostatins in brain reward function. Importantly, the discrete trial ICSS procedure used in this study allows the assessment of reward thresholds that are independent of response rates and are not affected by nonspecific motor effects of manipulations (Markou and Koob, 1992). Thus, a major advantage of this procedure is that it provides a quantitative measure of reward (brain reward thresholds measured in μA) that is extremely stable over periods of months under baseline conditions, allows repeated testing of subjects, and shows predictable and reliable effects of pharmacological manipulations on brain reward function (Kornetsky et al., 1979; Markou and Koob, 1992; Vlachou and Markou, 2010 in press).

In summary, in the present study, we assessed the effects of i.c.v. somatostatin-28 administration on complex locomotor and investigatory behavior, brain reward function, and sensorimotor gating in rats. Spontaneous locomotor and exploratory activity was measured in a behavioral pattern monitor (BPM; Geyer et al. 1986). Sensorimotor gating was assessed using PPI of the acoustic startle reflex. Brain reward function was measured in a discrete-trial ICSS threshold procedure (Markou and Koob, 1992). Somatostatin-28 was selected for the present studies because it is a more stable compound and has a longer plasma half-life than somatostatin-14 (Patel, 1999). Additionally, we evaluated the effects of SRA-880 ([3R,4aR,10aR]-1,2,3,4,4a,5,10,10a-octahydro-6-methoxy-1-methyl-benz[g] quinoline-3-carboxylic-acid-4-(4-nitro-phenyl)-piperazine-amide, hydrogen malonate), a nonpeptide sst1 receptor antagonist (Hoyer et al., 2004), on PPI and brain reward function in the ICSS procedure. SRA-880 was selected to be used in these studies as one of the first non-peptide receptor antagonists available for basic science investigations. We have shown previously that the sst1 receptor has an autoreceptor function in the retina, hypothalamus, and the nucleus accumbens (Thermos et al., 2006) and most recently in the hippocampus (De Bundel et al., 2010); some of these findings were made possible by the use of SRA880, both in vitro and in vivo. The role of sst1 receptors in sensorimotor gating and reward processes are not known. Because somatostatin-28 did not have a robust effect on motor behavior, the effects of SRA-880 on locomotor and investigatory activity were not evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Male Wistar rats (Charles River; Raleigh, NC) weighing 300–350 g at the beginning of the experiments were housed in groups of two in a humidity- and temperature-controlled vivarium on a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. Rats had ad libitum access to food and water throughout the course of the studies except during testing. Training and testing occurred during the dark cycle. All experiments were in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Drugs

Somatostatin-28 (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) was dissolved in saline and administered i.c.v.. The i.c.v. injection volume was 5 μl of drug/saline solution per side infused over 30 s using a Hamilton 10 μl microsyringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) connected to the injection cannula via polyethylene tubing. A stainless-steel injector was 3 mm longer than the guide cannula so that its tip protruded into the ventricle. After each infusion, 7 mm stylets were placed into the cannula to prevent unnecessary blockage. SRA-880 (Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) was dissolved in a mixture of 20% 1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinone and 80% of a 5% D-glucose nanopure water solution. SRA-880 was injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in a volume of 1 ml/kg. Control rats were injected with appropriate vehicle solutions.

2.3. Intracranial electrode and cannula implantation surgery and placement verification

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–3%) in an oxygen vapor mixture. Subjects were prepared with bipolar stainless steel electrodes (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) in the posterior lateral hypothalamus (anterior/posterior, −0.5 mm from bregma; lateral, ± 1.7 mm; dorsal/ventral, −8.3 mm from dura with the incisor bar elevated 5.0 mm above the interaural line; (Pellegrino et al., 1986). During the same surgery, guide cannulas (23 gauge; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were implanted bilaterally in the lateral ventricles (anterior/posterior, 0.6 mm from bregma; lateral, + 2.0 mm; dorsal/ventral, 3.0 mm from dura with the incisor bar elevated 5.0 mm above the interaural line; Pellegrino et al., 1986). At the end of the experiments, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital and perfused via the ascending aorta with physiological saline (100 ml) followed by a 10% formalin solution. Coronal sections were sliced on a cryostat and stained with cresyl violet to verify the infusion sites. Animals with accurate cannula placements were included in the statistical analyses.

2.4. Behavioral pattern monitor (BPM)

Behavior was measured in a BPM which consisted of a 30.5 × 61.0 cm black Plexiglas chamber equipped with 2.5 cm holes in the walls and floor as described previously (Geyer et al., 1986). Photocells in each hole detected investigatory nosepokes (holepokes). A touchplate located 15.2 cm above the floor allowed the detection of rearings when the animal made contact between the metal floor and the metal touchplate. A 4 × 8 grid of infrared photobeams detected the animal’s position in the X–Y plane. A computer continuously monitored all photobeams and the touchplate and stored the data for later analysis. The BPM system collected data on 23 behavioral measures, including the number of holepokes, rearings, and locomotor activity. Three types of locomotor activity measures were derived. Movements were defined as the total number of X-Y beam breaks. Crossings were quantified by the number of crossings between any of eight equal square sectors within the BPM and required whole-body translocations for scoring. Region entries were defined as the number of entries into and time spent in the center and corners of the apparatus. A 60 min period of habituation to the testing room occurred before the test. The test session duration was 60 min. Data were analyzed in 10 min time bins.

2.5. Acoustic startle procedure

Four startle chambers (SR-LAB system, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) were used. The startle chambers consisted of a Plexiglas cylinder, 8.2 cm diameter, resting on a 12.5 × 25.5 cm Plexiglas frame within a sound-attenuated ventilated enclosure. Acoustic startle was produced by a loudspeaker mounted 24 cm above the Plexiglas cylinder. A piezoelectric accelerometer on the base of the cylinder frame detected and transduced vibration, which was digitized and recorded by an interface unit and computer. Sound levels (dB [A] scale) and accelerometer sensitivities within each chamber were calibrated regularly and remained constant throughout the experiment.

After the rats were placed in the startle chambers, the 70 dB background noise was presented for a 5 min acclimation period and continued throughout the test session. During a test session, all trial types were presented several times in a pseudorandom order for a total of 107 trials (18 120 dB pulse-alone trials, 53 no stimulus [nostim] trials, 18 76 dB prepulse + 120 dB pulse trials, and 18 82 dB prepulse + 120 dB pulse trials). Additionally, six pulse-alone and six nostim trials, which were not included in the calculation of PPI values (based on the observation that the most rapid habituation of the startle reflex occurs within the first few presentations of the startling stimulus; Geyer et al., 1990), were presented at the beginning of each test session, and six additional pulse-alone 120 dB and six nostim trials were presented at the end of each test session to assess startle habituation throughout the session. The time between trials averaged 15 s (range, 12–30 s), and the total duration of a test session was approximately 16.5 min. The pulse-alone trial consisted of a 40 ms 120 dB pulse of broadband noise. The prepulse + pulse trials consisted of a 20 ms noise prepulse, a 100 ms delay, then a 40 ms 120 dB startle pulse (120 ms onset-to-onset interval). Prepulse intensities were 3, 6, and 12 dB above the 70 dB background level, and each prepulse trial was designated as 73 dB prepulse + pulse, 76 dB prepulse + pulse, and 82 dB prepulse + pulse. The nostim trial consisted of background noise only and allowed the assessment of general activity in the startle chamber by the piezoelectric accelerometer when no acoustic stimuli were presented.

2.6. Intracranial self-stimulation apparatus and procedure

The discrete-trial current-threshold ICSS procedure was a modification of a procedure originally developed by Kornetsky and colleagues (Kornetsky et al., 1979) and has been described in detail by Markou and Koob (Markou and Koob, 1991, 1992). Briefly, training and testing occurred in 16 sound-attenuated Plexiglas chambers (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) that contained a metal wheel manipulandum. Brain stimulation was delivered by constant-current stimulators (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). At the start of each trial, rats received a noncontingent electrical stimulus (100 Hz rectangular cathodal pulses). During the following 7.5 s limited hold, if the rats responded by turning the wheel manipulandum (positive response), then they received a second contingent stimulus identical to the previous noncontingent stimulus. During a 2 s period immediately after a positive response, further responses had no consequences. If no response occurred during the 7.5 s limited hold, a negative response was recorded. The intertrial interval (ITI), which followed the limited hold period, had an average duration of 10 s (range 7.5–12.5 s). Responses occurring during the ITI resulted in a further 12.5 s delay of the onset of the next trial. Stimulation intensities varied according to the psychophysical method of limits. Rats received four alternating series of ascending and descending current intensities, beginning with a descending series. Within each series, the stimulus intensity was altered by 5 μA steps between each set of trials (three trials per set). The initial stimulus intensity was set at 30–40 μA above the baseline current threshold for each rat. A test session typically lasted 30 min and provided current-intensity thresholds as the dependent variable. The threshold for each descending series was defined as the stimulus intensity between the successful completion of a set of trials (two consecutive sets), during which the rat failed to respond positively on two or more of the three trials for two consecutive steps. For the ascending series, the reverse situation defined the threshold. Current thresholds were recorded for each of the four series, and the mean of these values was taken as the threshold for that session. Baseline reward thresholds were considered stable when less than 10% variation occurred over 5 consecutive days. The latency between the onset of the noncontingent stimulus at the start of each trial and a positive response was recorded as the response latency. The response latency for each test session was defined as the mean response latency of all trials during which a positive response occurred.

2.7. Experimental design

2.7.1. Experiment 1. Effects of somatostatin-28 on spontaneous locomotor behavior

Rats (n = 32) were prepared with i.c.v. cannulae and injected with somatostatin-28 (0, 1.0, 3.16, or 10 μg/5 μl per side) 10 min before the test session according to a between-subjects experimental design. Nine rats were excluded from the analyses due to lost head mounts and misplaced cannulas resulting in n = 4–8 per experimental group.

2.7.2. Experiment 2. Effects of somatostatin-28 alone or combined with the sst1 receptor antagonist SRA-880 on the startle response and PPI

Twenty-three rats from Experiment 1 and ten drug-naive rats were used according to a between-subjects experimental design (n = 33 total; four groups, n = 8–9/group). Drug-naïve animals were added in Experiment 2 as controls for potential carry-over effects of somatostatin-28 administration on startle and PPI in rats used after the completion of testing in Experiment 1. Rats were assigned to treatment groups in a counterbalanced manner so that each re-used rat received a different dose of somatostatin-28 than in Experiment 1, and the same number of previously used rats were assigned to each of the four groups in Experiment 2. Somatostatin-28 (0, 1.0, 3.16, or 10.0 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.) was administered 10 min before the test session.

The same subjects (n = 33) were used to evaluate the effects of the somatostatin-28 and SRA-880 combination on the startle response and PPI according to a between-subjects crossover experimental design. In the first crossover design, rats were administered SRA-880 (10 mg/kg, s.c.) or vehicle and somatostatin-28 (10 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.) or vehicle. In the second crossover design, rats were administered SRA-880 (20 mg/kg, s.c.) or vehicle and somatostatin-28 (10 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.) or vehicle. Pretreatment times were 10 min for somatostatin-28 and 45 min for SRA-880.

For the crossover design experiment, five rats out of 33 were excluded from the first part of the cross-over experiment resulting in n = 28, and and six rats were excluded from these remaining 28 resulting in n = 22 for the second part of this cross-over experiment. These rats were excluded due to cannulae loss or blockage.

2.7.3. Experiment 3. Effects of somatostatin-28 and SRA-880 on brain reward function

Naive rats were prepared with i.c.v. cannulae and ICSS electrodes. Rats were trained in the ICSS procedure until stable baseline responding was achieved (less than 10% variation over 5 days). Rats were divided into two groups. Somatostatin-28 (0, 1.0, 3.16, or 10.0 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v., n = 8) or SRA-880 (0, 1, 5, or 10 mg/kg, s.c., n = 9) were administered 10 min or 45 min, respectively, before the test session according to a within-subjects Latin square design for each of the two compounds.

2.8. Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using the Biomedical Computer Programs for Personal Computers Statistical Package (BMDP, Los Angeles, CA) using the appropriate mixed-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant interactions were followed by Newman Keuls post hoc test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.8.1. BPM data analyses

The following variables were obtained from the raw data: the number of crossings, movements, holepokes and rearings; the number of entries; and the amount of time spent in a particular region (center, walls, and corners). Data were analyzed in 10 min time bins using a two-way ANOVA, with Time the repeated measure and Somatostatin-28 dose the between-subjects factor.

2.8.2. Startle and PPI data analyses

Startle habituation was calculated as the average response to all of the pulse-alone trials presented in blocks 1–4 during the test session. Prepulse inhibition was calculated as a percentage score for each prepulse trial type: % PPI = 100 – ([startle response for prepulse + pulse]/[startle response for pulse-alone])×100. In PPI data analyses, startle response was calculated as the average response to all of the pulse-alone trials, excluding the first and last blocks of six pulse-alone trials. Startle amplitude and PPI values were analyzed using an ANOVA, with Drug dose (Somatostatin-28 and SRA-880) the between-subjects factor and Block and Prepulse intensities the within-subjects factors.

2.8.3. ICSS data analyses

ICSS thresholds and response latencies were expressed as a percentage of baseline values assessed on the day before the drug treatments. One-way ANOVA was used for data analyses, with Drug dose (e.g., four levels) as the within-subjects factor. For the testing of a priori hypotheses relating to the somatostatin-28-induced threshold elevations group comparisons were made using paired t-tests in addition to post-hoc tests after statistically significant effects in the ANOVAs.

3. Results

Twenty rats total were excluded from Experiments 1 and 2 because of cannulae misplacements, loss or blockage. For the remaining subjects, the tips of the injectors were all found to be within the lateral ventricle.

3.1. Experiment 1. Effects of somatostatin-28 on spontaneous locomotor behavior

The data on the effects of somatostatin-28 on spontaneous locomotor behavior is presented in Table 1. Overall ANOVA indicated a significant Time × Somatostatin-28 treatment interaction on the number of crossings (F15,95 = 2.69, p < 0.001), total movements (F15,95 = 2.51, p < 0.05), the number of corner entries (F15,95 = 2.43, p < 0.05), and the number of wall area entries (F15,95 = 1.82, p < 0.05). However, there was no Time × Treatment interaction for the number of center entries, the number of holepokes, or the number of rears (data not shown).

Table 1.

Dose (1–10 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.)-response relationship of somatostatin-28 treatment on locomotor activity across a 60 min testing session.

| Dose | N | 1–10 min | 11–20 min | 21–30 min | 31–40 min | 41–50 min | 51–60 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crossings | |||||||

| veh | 4 | 244.0 ± 22.1 | 125.7 ± 20.4 | 61.5 ± 23.3 | 34.8 ± 20.6 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 50.0 ± 29.3 |

| 1 | 7 | 160.9 ± 15.2 | 82.9 ± 15.0 | 59.3 ± 11.9 | 38.0 ± 10.7 | 28.1 ± 7.1 | 47.1 ± 10.3 |

| 3.16 | 4 | 193.5 ± 35.9 | 100.5 ± 29.0 | 63.2 ± 24.8 | 41.8 ± 19.3 | 55.5 ± 25.3 | 34.0 ± 10.5 |

| 10 | 8 | 143.2 ± 29.4 | 91.9 ± 15.7 | 66.9 ± 8.3 | 44.3 ± 11.4 | 25.6 ± 8.54 | 34.5 ± 9.8 |

| F3,19 = 2.84 | F3,19 = 1.0 | F3,19 = 0.08 | F3,19 = 0.11 | F3,19 = 3.2 | F3,19 = 0.41 | ||

| p < 0.065, ns | ns | ns | ns | p < 0.05 | ns | ||

| Wall region entries | |||||||

| veh | 4 | 209.8 ± 18.7 | 134.3 ± 16.8 | 73.5 ± 29.8 | 40.5 ± 20.1 | 7.5 ± 6.8 | 59.0 ± 31.8 |

| 1 | 7 | 170.1 ± 11.1 | 95.9 ± 14.7 | 71.0 ± 11.1 | 47.7 ± 12.9 | 36.6 ± 9.7 | 59.1 ± 11.0 |

| 3.16 | 4 | 168.8 ± 20.1 | 109.0 ± 21.3 | 70.0 ± 20.9 | 52.2 ± 30.2 | 57.0 ± 22.8 | 37.3 ± 8.1 |

| 10 | 8 | 148.8 ± 24.6 | 106.1 ± 11.3 | 83.5 ± 11.9 | 61.8 ± 17.1 | 38.5 ± 11.1 | 47.5 ± 13.3 |

| F3,19 = 1.54 | F3,19 = 1.0 | F3,19 = 0.22 | F3,19 = 0.36 | F3,19 = 2.21 | F3,19 = 0.44 | ||

| ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Corner entries | |||||||

| veh | 4 | 145.0 ± 17.7 | 99.0 ± 5.0 | 54.3 ± 18.0 | 31.5 ± 13.2 | 7.5 ± 5.6 | 7.3 ± 3.7 |

| 1 | 7 | 128.3 ± 11.5 | 70.1 ± 10.3 | 53.9 ± 9.5 | 33.7 ± 8.3 | 27.0 ± 7.3 | 7.7 ± 1.4 |

| 3.16 | 4 | 109.75 ± 13.8 | 76.8 ± 17.1 | 52.7 ± 17.0 | 41.0 ± 7.5 | 43.8 ± 16.8 | 5.0 ± 1.2 |

| 10 | 8 | 90.9 ± 13.2 | 72.9 ± 8.0 | 58.4 ± 8.6 | 44.5 ± 11.4 | 31.9 ± 9.2 | 4.25 ± 1.4 |

| F3,19 = 3.41 | F3,19 = 1.55 | F3,19 = 0.06 | F3,19 = 0.36 | F3,19 = 2.0 | F3,19 = 1.16 | ||

| p < 0.05 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

| Movements | |||||||

| veh | 4 | 656.5 ± 60.8 | 393.5 ± 54.4 | 207.8 ± 66.0 | 124.8 ± 62.1 | 20.5 ± 15.5 | 177.2 ± 97.4 |

| 1 | 7 | 482.0 ± 31.9 | 279.4 ± 41.8 | 185.0 ± 30.7 | 134.3 ± 29.9 | 91.1 ± 21.9 | 144.9 ± 29.9 |

| 3.16 | 4 | 499.8 ± 51.1 | 298.8 ± 57.8 | 203.8 ± 69.6 | 143.0 ± 50.0 | 154.5 ± 62.8 | 109.0 ± 33.3 |

| 10 | 8 | 412.8 ± 72.2 | 297.9 ± 34.6 | 222.1 ± 27.0 | 152.6 ± 36.8 | 96.4 ± 29.4 | 121.3 ± 31.9 |

| F3,19 = 2.90 | F3,19 = 1.28 | F3,19 = 0.22 | F3,19 = 0.10 | F3,19 = 2.36 | F3,19 = 0.43 | ||

| p < 0.062, ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

Values (including arbitrary units) are expressed as mean ± SEM. N, number of subjects per group; ns, not significant.

Additional ANOVAs were performed on each of six 10 min intervals for each behavioral measure, and a significant Time × Treatment interaction was found (Table 1). Somatostatin-28 significantly decreased the number of corner entries and tended to decrease the number of crossings and total movements during the first 10 min of testing (Table 1). However, post hoc analyses did not reveal any significant differences between treatment groups.

3.2. Experiment 2. Effects of somatostatin-28 alone or combined with the sst1 receptor antagonist SRA-880 on the startle response and PPI

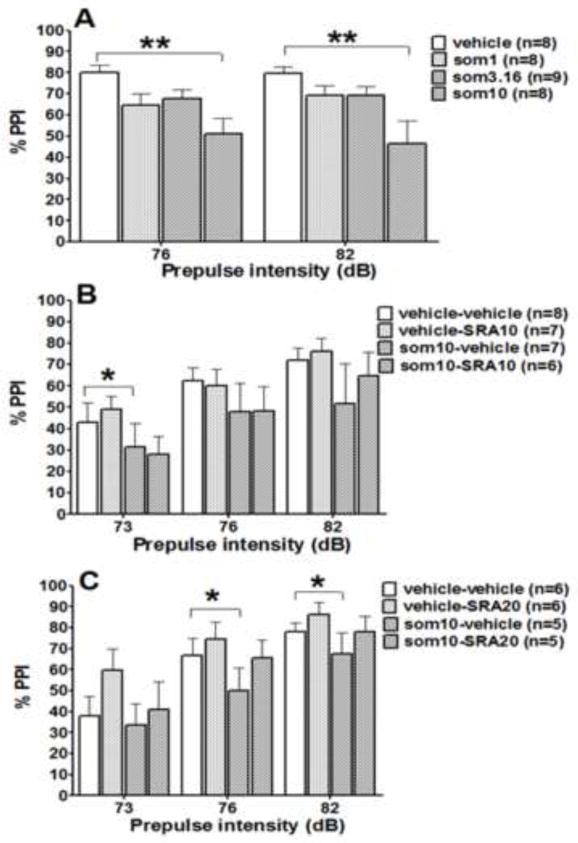

Somatostatin-28 administration had no effect on startle amplitude, indicating similar habituation of the startle response between treatment groups (Table 2). ANOVA of startle amplitude values revealed a significant effect of Block (F4,116 = 47.31, p < 0.0001) but no effect of Somatostatin-28 treatment (F3,29 = 0.55, p > 0.05) and no Treatment × Block interaction (F12,116 = 0.37, p > 0.05). ANOVA of the PPI data indicated a significant effect of Somatostatin-28 treatment (F3,29 = 5.4, p < 0.01) but no effect of Prepulse intensity (F1,29 = 0.06, p > 0.05) and no Somatostatin-28 treatment × Prepulse intensity interaction (F3,29 = 1.24, p > 0.05]. Post hoc analyses revealed that the highest somatostatin-28 dose (10 μg/5 μl) significantly decreased PPI at both the 76 and 82 dB prepulse intensities (Newman-Keuls post hoc test, p < 0.01; Fig. 1A).

Table 2.

Effects of somatostatin-28 (1–10 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.) alone or combined with SRA-880 (10 or 20 mg/kg, s.c.) on startle response amplitude.

| Treatment | N | Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vehicle | 8 | 1116.8 ± 220.3 | 403.5 ± 89.1 | 541.9 ± 142.5 | 372.5 ± 102.9 |

| SST 1.0 | 8 | 954.6 ± 96.6 | 491.3 ± 115.5 | 485.1 ± 118.9 | 402.3 ± 71.5 |

| SST 3.16 | 9 | 1083.5 ± 144.3 | 461.4 ± 112.5 | 461.2 ± 114.8 | 391.7 ± 75.0 |

| SST 10.0 | 8 | 1239.4 ± 256.7 | 707.5 ± 159.7 | 631.0 ± 194.8 | 580.5 ± 179.2 |

| vehicle+vehicle | 8 | 856.3 ± 92.3 | 471.4 ± 73.4 | 412.6 ± 76.7 | 268.2 ± 58.9 |

| vehicle+SRA-880 10.0 | 7 | 1107.5 ± 134.5 | 552.2 ± 120.3 | 362.5 ± 42.4 | 213.1 ± 33.5 |

| SST 10.0+vehicle | 7 | 1059.7 ± 148.2 | 500.0 ± 95.1 | 436.5 ± 90.1 | 270.8 ± 56.4 |

| SST 10.0+SRA-880 10.0 | 6 | 766.9 ± 88.6 | 388.0 ± 62.1 | 317.9 ± 36.1 | 297.9 ± 56.1 |

| vehicle+vehicle | 6 | 455.3 ± 137.3 | 566.0 ± 170.6 | 469.6 ± 141.6 | 554.8 ± 167.3 |

| vehicle+SRA-880 20.0 | 6 | 522.3 ± 174.1 | 494.5 ± 164.9 | 282.8 ± 94.3 | 643.0 ± 214.3 |

| SST 10.0+vehicle | 5 | 327.0 ± 98.6 | 334.3 ± 100.8 | 520.1 ± 156.8 | 455.8 ± 137.4 |

| SST 10.0+SRA-880 20.0 | 5 | 548.3 ± 182.5 | 328.1 ± 109.4 | 198.2 ± 66.1 | 105.3 ± 35.1 |

Values (arbitrary units) are expressed as mean startle amplitude ± SEM. Startle response is presented in blocks 1–4. SST, somatostatin-28; N, number of subjects per group.

Figure 1.

Effects of somatostatin-28 alone (A) and combined with SRA-880 on prepulse inhibition (PPI). Data are expressed as mean % PPI ± SEM. PPI was tested at three prepulse intensities (73, 76, and 82 dB). SRA-880 at the low dose of 10 mg/kg (B) and high dose of 20 mg/kg (C) was administered either alone or combined with somatostatin-28 (10 μg/5 μl per side). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significant difference from control group (Newman-Keuls post hoc test).

The low SRA-880 dose (10 mg/kg) had no effect on startle response habituation (Table 2). ANOVA of the startle amplitude values revealed no SRA-880 treatment effect (F1,26 = 0.16, p > 0.05) but a significant effect of Somatostain-28 treatment (F7,182 = 40.12, p < 0.001) and a significant Somatostatin-28 × SRA-880 interaction (F7,182 = 3.30, p < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons did not reveal significant differences between treatment groups (Table 2). Somatostatin-28 decreased PPI (F1,26 = 8.55, p < 0.01), but this effect was significant only at a prepulse intensity of 73 dB (Fig. 1B). The low SRA-880 dose of 10 mg/kg had no effect on PPI when administered alone (F1,26 = 0.22, p > 0.05) or when combined with Somatostatin-28 (interaction effect: F1,26 = 0.03, p > 0.05). A significant effect of Prepulse intensity was observed (F2,52 = 41.24, p < 0.0001), independent of drug treatment (no Prepulse intensity × SRA-880 × Somatostatin-28 interaction: F2,52 = 1.58, p > 0.05).

The high SRA-880 dose (20 mg/kg) had no effect on startle response habituation (Table 2). ANOVA of startle the amplitude values revealed no SRA-880 treatment effect (F1,20 = 0.25, p > 0.05) but a significant effect of Somatostain-28 treatment (F7,140 = 16.51, p < 0.001). No significant Somatostatin-28 × SRA-880 interaction was found (Table 2). Replicating the previous results, ANOVA indicated that somatostatin-28 decreased PPI (F1,20 = 8.07, p < 0.01), and this effect was significant at prepulse intensities of 76 and 82 dB (Fig. 1C). A strong tendency was observed toward SRA-880 (20 mg/kg) reversing PPI deficits induced by somatostatin-28 (SRA-880 treatment: F1,20 = 3.93, p < 0.061; Somatostatin-28 × SRA-880 × Prepulse intensity interaction: F2,40 = 2.94, p < 0.064; Fig. 1C).

3.3. Experiment 3. Effects of somatostatin-28 and SRA-880 on brain reward function

Mean group absolute values for ICSS thresholds and response latencies obtained on the days prior to somatostatin-28 administration ranged from 110.31 ± 18.31 μA to 115.63 ± 18.5 μA and from 3.15 ± 0.18 s to 3.40 ± 0.26 s, respectively. Somatostatin-28 significantly elevated brain reward thresholds (F3,21 = 3.34, p < 0.05) at the highest doses of 3.16 and 10 μg/μl compared with vehicle (Table 3). Somatostatin-28 treatment had no effect on response latencies (F3,21 = 1.97, n.s.).

Table 3.

Brain reward thresholds and response latencies after acute administration of somatostatin-28 and SRA-880.

| Dose | Threshold (% baseline) | Response latency (% baseline) |

|---|---|---|

| Somatostatin-28 (μg/5 μl, i.c.v., n = 8) | ||

| vehicle | 100.07 ± 1.66 | 103.86 ± 3.28 |

| 1 | 104.52 ± 4.11 | 95.34 ± 3.15 |

| 3.16 | 121.72 ± 10.98*# | 101.89 ± 4.27 |

| 10 | 117.95 ± 6.57# | 105.25 ± 2.76 |

| SRA-880 (mg/kg, s.c., n = 9) | ||

| vehicle | 105.92 ± 3.34 | 103.03 ± 3.68 |

| 1 | 105.18 ± 2.94 | 109.47 ± 3.83 |

| 5 | 113.75 ± 3.62 | 103.98 ± 3.48 |

| 10 | 103.93 ± 1.74 | 100.27 ± 3.03 |

Data are expressed as a percentage of baseline thresholds and response latencies measured the day before the drug treatment day (mean ± SEM).

p < 0.05, significant difference from the corresponding vehicle condition (Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc test);

p < 0.05, significant difference from vehicle condition (paired t-test).

Mean group absolute values for ICSS thresholds and response latencies obtained on the days prior to SRA-880 administration ranged from 150.37 ± 18.95 μA to 159.58 ± 25.12 μA and from 3.05 ± 0.16 s to 3.21 ± 0.13 s, respectively. SRA-880 treatment had no effect on brain reward thresholds (F3,24 = 2.77, n.s., Table 3) or response latencies (F3,24 = 1.10, n.s., Table 3).

4. Discussion

In the BPM, i.c.v. injections of somatostatin-28 decreased spontaneous locomotor activity during the first 10 min after injection with no apparent changes in exploratory activity (i.e., the number of hole-pokes and rears) in rats. The highest somatostatin-28 dose (10 μg/5 μl per side) significantly decreased PPI with no effect on the amplitude of the acoustic startle response or startle response habituation. Administration of SRA-880 tended to reverse the somatostatin-induced deficits in PPI. SRA-880 had no effect on either the startle response or PPI when administered alone. Administration of somatostatin-28, but not SRA-880, induced elevations in brain reward thresholds, reflecting a decrease in brain reward function.

In the present study, i.c.v. administration of somatostatin-28 decreased spontaneous locomotor, but not exploratory activity, mainly due to decreases in crossings, corner entries and movements during the first 10 min of testing. Previously published findings on the effects of somatostatin on locomor activity provided mixed results. Specifically, somatostatin, at doses of 1 μg or 4 μg i.c.v., increased locomotor activity, 10 μg decreased rearings, and 6 nM decreased locomotor activity and rears during a 3 min open field test (Vecsei et al., 1984; Vecsei and Widerlov, 1988b, 1990). Additionally, administration of cysteamine, which is known to deplete somatostatin levels in the brain (Sagar et al., 1982), markedly decreased open field activity (Vecsei et al., 1989) and attenuated the motor response to dopaminergic receptor agonists after either systemic or central administration (Martin-Iverson et al., 1986; Lee et al., 1988). However, the somatostatin-induced increases in locomotion in these studies may be attributed to anxiety-related behaviors induced by the open field test (Holmes et al., 2002). Recent studies implicated somatostatins in anxiety and depression (Kluge et al., 2008; Pallis et al., 2009). Studies using sst2 receptor knockout mice reported decreased locomotor and exploratory responses in stress-inducing situations measured in an open field (Viollet et al., 2000) and unchanged levels of locomotor activity in undemanding tasks (Zeyda et al., 2001; Allen et al., 2003). Furthermore, recent findings showed anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects of i.c.v.-administered somatostatin in the elevated plus maze and forced swim test, respectively (Engin et al., 2008). In the fear-potentiated startle procedure, which assesses anxiety-related behaviors and is predictive of anxiolytic properties of drugs (Davis et al., 1993), octreotide blocked fear-potentiated startle, further implicating somatostatin in anxiety-like behaviors (Fendt et al., 1996) see also (Kluge et al., 2008). Thus, increases in locomotor activity after somatostatin administration can be observed in anxiogenic situations. In the present study, locomotor activity was assessed under no or low stress conditions, and somatostatin decreased spontaneous locomotor activity with no significant effects on exploratory behavior.

Additionally, differential effects of somatostatin on locomotor behavior have been shown to be brain site-specific. Intra-nucleus accumbens injections of somatostatin (3.2–100 ng/side) significantly increased locomotor activity, and this effect was mediated by sst2 receptors (Raynor et al., 1993). Somatostatin also dose-dependently increased locomotor activity when administered into the globus pallidus (Marazioti et al., 2008), decreased locomotor activity when administered into the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata (Marazioti et al., 2005), and had biphasic effects when administered into the caudate putamen (Tashev et al., 2001). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that somatostatin and its receptors located in nuclei of the basal ganglia are implicated in motor control and locomotion when somatostatin is administered into specific brain sites, but not after i.c.v. administration as in the present study.

The role of somatostatin in sensorimotor gating has not been studied extensively. Early work implicated somatostatins in the maturation of sensorimotor information processing by showing that chronic application of cysteamine, a sulfhydryl agent that decreases somatostatin levels, in developing rats significantly reduced startle amplitude in rats on postnatal day 18 (Kungel et al., 1996). In the present study, i.c.v. administration of somatostatin-28 had no effect on acoustic startle amplitude and habituation of the startle reflex. Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that octreotide had no effect on baseline startle amplitude when administered into the caudal pontine reticular nucleus (Fendt et al., 1996). Furthermore, somatostatin-28 induced PPI deficits when administered at the highest dose (10 μg/5 μl per side, i.c.v.). Somatostatin-induced increases in dopaminergic neurotransmission (Thermos et al., 1996; Hathway et al., 1998; Pallis et al., 2001; Rakovska et al., 2002; Rakovska et al., 2003; Marazioti et al., 2008) may underlie the observed PPI deficits, similar to the PPI-disruptive effects of psychostimulants, a putative model of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (Geyer and Ellenbroek, 2003). Thus, somatostatin antagonists or depletors may exert dopamine-inhibitory effects, suggesting neuroleptic-like properties. Consistent with this hypothesis, cysteamine administration reversed amphetamine-induced PPI deficits (Feifel and Minor, 1997), similar to the reversal of psychostimulant-induced PPI deficits by typical and atypical antipsychotics (Geyer et al., 1990; Geyer et al., 2001; Ralph and Caine, 2005; Geyer, 2006). In the present study, the somatostatin-induced PPI deficit was partially reversed by SRA-880 administration. Somatostatin-induced increases in dopaminergic transmission have been shown to be mediated by sst2 receptors (Hathway et al., 1999). SRA-880 is a selective sst1 receptor antagonist with no effect on other types of somatostatin receptors; therefore, only partial reversal of somatostatin-induced PPI deficits by SRA-880 was observed in the present study. Alternatively, in the presence of inhibitory tone, the sst1 autoreceptor antagonist SRA-880 may produce an increase in local somatostatin release (De Bundel et al., 2010), resulting in the partial reversal of somatostatin-induced PPI deficits. Administration of the sst1 receptor antagonist SRA-880 alone had no effect on either startle amplitude or PPI. Similarly, systemic administration of cysteamine had no effect on baseline startle response or PPI (Feifel and Minor, 1997). Additionally, in genetically modified mice, both the acoustic startle response and the level of PPI did not differ between wildtype and sst2lacZ/lacZ knockout mice (Allen et al., 2003) or somatostatin peptide knockout mice (Zeyda et al., 2001).

In the present study, somatostatin-28 (3.16 and 10 μg/5 μl per side) induced threshold elevations, indicating deficits in brain reward function. SRA-880 had no effect on brain reward function at any dose tested. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that somatostatin induced robust decreases in self-stimulation behavior in the rate-frequency self-stimulation procedure (Vecsei et al., 1982, 1983; Balazs et al., 1988). Somatostatin-induced response depression in the rate frequency ICSS procedure was potentiated by co-administration with the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist haloperidol, the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline, the α adrenergic receptor antagonist phenoxybenzamine, and the rather nonselective serotonin 5-HT1/5-HT2 receptor ligand methysergide (Vecsei et al., 1982, 1983; Balazs et al., 1988). By contrast, atropine, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, partially reversed the effects of somatostatin (Vecsei et al., 1983). These findings clearly indicate that multiple neurotransmitter systems may be involved in the effects of somatostatin on brain reward function.

Dopaminergic neurotransmission is one the systems that mediate motivation and reward, suggesting its role in somatostatin-induced anhedonia. Drugs that block dopamine neurotransmission (e.g., dopamine receptor antagonists) are well known to induce reward deficits, reflected by elevations in brain reward thresholds (e.g., (Baldo et al., 1999; Bruijnzeel and Markou, 2005). Conversely, drugs that indirectly facilitate dopamine transmission (e.g., monoamine reuptake inhibitors) induced brain reward facilitation, reflected by decreases in brain reward thresholds (Lin et al., 2000; Kenny et al., 2003; Mague et al., 2005). In vivo microdialysis studies in rats showed that somatostatin increased dopamine release in the striatum and nucleus accumbens (Thermos et al., 1996; Hathway et al., 1998; Pallis et al., 2001; Rakovska et al., 2002; Rakovska et al., 2003; Marazioti et al., 2008). Several lines of evidence indicate that the nucleus accumbens shell is functionally associated with the mesolimbic dopamine system involved in reward processes, and the nucleus accumbens core is functionally related to the nigrostriatal dopamine system associated with motor function (Deutch and Cameron, 1992; Deutch, 1993; Pontieri et al., 1995; David et al., 2005; Bassareo et al., 2007). Thus, somatostatin-induced dopamine release in the striatum and nucleus accumbens core may mediate the effects of somatostatin on motor behavior. Although the effects of somatostatin on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell are not known, based on the demonstrated somatostatin-induced reward deficits, somatostatin may decrease dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens shell.

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide further information on the behavioral effects of somatostatin-28. Based on the demonstrated involvement of somatostatin-28 in brain reward function and sensorimotor gating, our findings suggest that increased somatostatin transmission may be one of the neurochemical mechanisms underlying anhedonia, one of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and sensorimotor gating deficits associated with cognitive impairments in schizophrenia patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Jessica Benedict and Mrs. Virginia Masten for excellent technical assistance, and Mr. Michael Arends for excellent editorial assistance.

Sources of support

This work was supported by NIH grants R01MH062527 (AM), DA002925 (MAG) and VISN22 MIRECC (MAG).

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest

DH is a full-time employee of Novartis. MAG holds an equity interest in San Diego Instruments, Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen JP, Hathway GJ, Clarke NJ, Jowett MI, Topps S, Kendrick KM, Humphrey PP, Wilkinson LS, Emson PC. Somatostatin receptor 2 knockout/lacZ knockin mice show impaired motor coordination and reveal sites of somatostatin action within the striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1881–1895. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Balazs M, Schwarzberg H, Telegdy G. Effects of somatostatin on self-stimulation behaviour in rats pretreated with a receptor blocker. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;149:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Jain K, Veraldi L, Koob GF, Markou A. A dopamine D1 agonist elevates self-stimulation thresholds: comparison to other dopamine-selective drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:659–672. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassareo V, De Luca MA, Di Chiara G. Differential impact of pavlovian drug conditioned stimuli on in vivo dopamine transmission in the rat accumbens shell and core and in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:689–703. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissette G. Effects of sertraline on regional neuropeptide concentrations in olfactory bulbectomized rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;69:269–281. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Human studies of prepulse inhibition of startle: normal subjects, patient groups, and pharmacological studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:234–258. doi: 10.1007/s002130100810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein M, Arimura A, Sato H, Schally AV, Kizer JS. The regional distribution of somatostatin in the rat brain. Endocrinology. 1975;96:1456–1461. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-6-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Markou A. Decreased sensitivity to the effects of dopamine D1-like, but not D2-like, receptor antagonism in the posterior hypothalamic region/anterior ventral tegmental area on brain reward function during chronic exposure to nicotine in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1058:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David HN, Ansseau M, Abraini JH. Dopamine-glutamate reciprocal modulation of release and motor responses in the rat caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens of “intact” animals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;50:336–360. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Falls WA, Campeau S, Kim M. Fear-potentiated startle: a neural and pharmacological analysis. Behav Brain Res. 1993;58:175–198. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90102-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bundel D, Aourz N, Kiagiadaki F, Clinckers R, Hoyer D, Kastellakis A, Michotte Y, Thermos K, Smolders I. Hippocampal sst(1) receptors are autoreceptors and do not affect seizures in rats. Neuroreport. 2010;21:254–258. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283353a64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY. Prefrontal cortical dopamine systems and the elaboration of functional corticostriatal circuits: implications for schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;91:197–221. doi: 10.1007/BF01245232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch AY, Cameron DS. Pharmacological characterization of dopamine systems in the nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience. 1992;46:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90007-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin E, Stellbrink J, Treit D, Dickson CT. Anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of intracerebroventricularly administered somatostatin: behavioral and neurophysiological evidence. Neuroscience. 2008;157:666–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelbaum J, Guillou JL, Gastambide F, Hoyer D, Duron E, Viollet C. Somatostatin, Alzheimer’s disease and cognition: an old story coming of age? Prog Neurobiol. 2009;89:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlmann D, Langenegger D, Schuepbach E, Siehler S, Feuerbach D, Hoyer D. Distribution and characterisation of somatostatin receptor mRNA and binding sites in the brain and periphery. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94:265–281. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)00208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D, Minor KL. Cysteamine blocks amphetamine-induced deficits in sensorimotor gating. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:689–693. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Koch M, Schnitzler HU. Somatostatin in the pontine reticular formation modulates fear potentiation of the acoustic startle response: an anatomical, electrophysiological, and behavioral study. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3097–3103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-09-03097.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA. Are cross-species measures of sensorimotor gating useful for the discovery of procognitive cotreatments for schizophrenia? Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:9–16. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.1/mgeyer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Ellenbroek B. Animal behavior models of the mechanisms underlying antipsychotic atypicality. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Russo PV, Masten VL. Multivariate assessment of locomotor behavior: pharmacological and behavioral analyses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25:277–288. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, McIlwain KL, Paylor R. Mouse genetic models for prepulse inhibition: an early review. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:1039–1053. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR, Mansbach RS, Braff DL. Startle response models of sensorimotor gating and habituation deficits in schizophrenia. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:485–498. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90241-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology. 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathway GJ, Humphrey PP, Kendrick KM. Evidence that somatostatin sst2 receptors mediate striatal dopamine release. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1346–1352. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathway GJ, Emson PC, Humphrey PP, Kendrick KM. Somatostatin potently stimulates in vivo striatal dopamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid release by a glutamate-dependent action. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1740–1749. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Wrenn CC, Harris AP, Thayer KE, Crawley JN. Behavioral profiles of inbred strains on novel olfactory, spatial and emotional tests for reference memory in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2002;1:55–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-1848.2001.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III--the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:549–562. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Bell GI, Berelowitz M, Epelbaum J, Feniuk W, Humphrey PP, O’Carroll AM, Patel YC, Schonbrunn A, Taylor JE, et al. Classification and nomenclature of somatostatin receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:86–88. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Nunn C, Hannon J, Schoeffter P, Feuerbach D, Schuepbach E, Langenegger D, Bouhelal R, Hurth K, Neumann P, Troxler T, Pfaeffli P. SRA880, in vitro characterization of the first non-peptide somatostatin sst(1) receptor antagonist. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:132–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Kotani A, Koshikawa N, Cools AR. Somatostatin receptors in the nucleus accumbens modulate dopamine-dependent but not acetylcholine-dependent turning behaviour of rats. Neuroscience. 2009;159:974–981. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, Koob GF, Markou A. Conditioned facilitation of brain reward function after repeated cocaine administration. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1103–1107. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.5.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge C, Stoppel C, Szinyei C, Stork O, Pape HC. Role of the somatostatin system in contextual fear memory and hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Learn Mem. 2008;15:252–260. doi: 10.1101/lm.793008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornetsky C, Esposito RU, McLean S, Jacobson JO. Intracranial self-stimulation thresholds: a model for the hedonic effects of drugs of abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:289–292. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780030055004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kungel M, Koch M, Friauf E. Cysteamine impairs the development of the acoustic startle response in rats: possible role of somatostatin. Neurosci Lett. 1996;202:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Radke JM, Vincent SR. Intra-cerebral cysteamine infusions attenuate the motor response to dopaminergic agonists. Behav Brain Res. 1988;29:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Koob GF, Markou A. Time-dependent alterations in ICSS thresholds associated with repeated amphetamine administrations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:407–417. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Andersen SL, Carlezon WA., Jr Early developmental exposure to methylphenidate reduces cocaine-induced potentiation of brain stimulation reward in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansbach RS, Geyer MA, Braff DL. Dopaminergic stimulation disrupts sensorimotor gating in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;94:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00212846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazioti A, Kastellakis A, Antoniou K, Papasava D, Thermos K. Somatostatin receptors in the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata modulate rat locomotor activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazioti A, Pitychoutis PM, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Spyraki C, Thermos K. Activation of somatostatin receptors in the globus pallidus increases rat locomotor activity and dopamine release in the striatum. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Koob GF. Postcocaine anhedonia. An animal model of cocaine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1991;4:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Koob GF. Construct validity of a self-stimulation threshold paradigm: effects of reward and performance manipulations. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90211-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Kenny PJ. Neuroadaptations to chronic exposure to drugs of abuse: relevance to depressive symptomatology seen across psychiatric diagnostic categories. Neurotox Res. 2002;4:297–313. doi: 10.1080/10298420290023963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Iverson MT, Radke JM, Vincent SR. The effects of cysteamine on dopamine-mediated behaviors: evidence for dopamine-somatostatin interactions in the striatum. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:1707–1714. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olias G, Viollet C, Kusserow H, Epelbaum J, Meyerhof W. Regulation and function of somatostatin receptors. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1057–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallis E, Thermos K, Spyraki C. Chronic desipramine treatment selectively potentiates somatostatin-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:763–767. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallis E, Vasilaki A, Fehlmann D, Kastellakis A, Hoyer D, Spyraki C, Thermos K. Antidepressants influence somatostatin levels and receptor pharmacology in brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:952–963. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel YC. Somatostatin and its receptor family. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1999;20:157–198. doi: 10.1006/frne.1999.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Markou A. Animal models and treatments for addiction and depression co-morbidity. Neurotox Res. 2007;11:1–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03033479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino L, Pellegrino A, Cushman A. A Stereotaxic Atlas of the Rat Brain. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Di Chiara G. Intravenous cocaine, morphine, and amphetamine preferentially increase extracellular dopamine in the “shell” as compared with the “core” of the rat nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12304–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovska A, Kiss JP, Raichev P, Lazarova M, Kalfin R, Milenov K. Somatostatin stimulates striatal acetylcholine release by glutamatergic receptors: an in vivo microdialysis study. Neurochem Int. 2002;40:269–275. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakovska A, Javitt D, Raichev P, Ang R, Balla A, Aspromonte J, Vizi S. Physiological release of striatal acetylcholine (in vivo): effect of somatostatin on dopaminergic-cholinergic interaction. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph RJ, Caine SB. Dopamine D1 and D2 agonist effects on prepulse inhibition and locomotion: comparison of Sprague-Dawley rats to Swiss-Webster, 129X1/SvJ, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2J mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:733–741. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynor K, Lucki I, Reisine T. Somatostatin receptors in the nucleus accumbens selectively mediate the stimulatory effect of somatostatin on locomotor activity in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow DR. Cerebrospinal fluid somatostatin and psychiatric illness. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21:341–365. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinow DR, Gold PW, Post RM, Ballenger JC. CSF somatostatin in affective illness and normal volunteers. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1985;9:393–400. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(85)90192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Landry D, Millard WJ, Badger TM, Arnold MA, Martin JB. Depletion of somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system by cysteamine. J Neurosci. 1982;2:225–231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-02-00225.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santis S, Kastellakis A, Kotzamani D, Pitarokoili K, Kokona D, Thermos K. Somatostatin increases rat locomotor activity by activating sst(2) and sst (4) receptors in the striatum and via glutamatergic involvement. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:181–189. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0346-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenova S, Markou A. Clozapine treatment attenuated somatic and affective signs of nicotine and amphetamine withdrawal in subsets of rats exhibiting hyposensitivity to the initial effects of clozapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1249–1264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siehler S, Nunn C, Hannon J, Feuerbach D, Hoyer D. Pharmacological profile of somatostatin and cortistatin receptors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Weiss F. The dopamine hypothesis of reward: past and current status. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Using an animal model of deficient sensorimotor gating to study the pathophysiology and new treatments of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:285–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashev R, Belcheva S, Milenov K, Belcheva I. Behavioral effects of somatostatin microinjected into caudate putamen. Neuropeptides. 2001;35:271–275. doi: 10.1054/npep.2001.0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thermos K, Bagnoli P, Epelbaum J, Hoyer D. The somatostatin sst1 receptor: an autoreceptor for somatostatin in brain and retina? Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thermos K, Radke J, Kastellakis A, Anagnostakis Y, Spyraki C. Dopamine-somatostatin interactions in the rat striatum: an in vivo microdialysis study. Synapse. 1996;22:209–216. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199603)22:3<209::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki A, Papasava D, Hoyer D, Thermos K. The somatostatin receptor (sst1) modulates the release of somatostatin in the nucleus accumbens of the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Widerlov E. Brain and CSF somatostatin concentrations in patients with psychiatric or neurological illness. An overview. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988a;78:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Widerlov E. Effects of intracerebroventricularly administered somatostatin on passive avoidance, shuttle-box behaviour and open-field activity in rats. Neuropeptides. 1988b;12:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Widerlov E. Effects of somatostatin-28 and some of its fragments and analogs on open-field behavior, barrel rotation, and shuttle box learning in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1990;15:139–145. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(90)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Klivenyi P. Somatostatin and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1995;21:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(95)00640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Schwarzberg H, Telegdy G. Comparative studies with linear and cyclic somatostatin on the self-stimulation of rats. Acta Physiol Acad Sci Hung. 1982;60:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Schwarzberg H, Telegdy G. The effect of somatostatin on self-stimulation behavior in atropine- and methysergide-pretreated rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;91:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Ekman R, Alling C, Widerlov E. Influence of cysteamine and cysteine on open-field behaviour, and on brain concentrations of catecholamines, somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and corticotropin releasing hormone in the rat. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1989;78:209–220. doi: 10.1007/BF01249230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecsei L, Kiraly C, Bollok I, Nagy A, Varga J, Penke B, Telegdy G. Comparative studies with somatostatin and cysteamine in different behavioral tests on rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;21:833–837. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(84)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SR, Johansson O. Striatal neurons containing both somatostatin- and avian pancreatic polypeptide (APP)-like immunoreactivities and NADPH-diaphorase activity: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1983;217:264–270. doi: 10.1002/cne.902170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollet C, Lepousez G, Loudes C, Videau C, Simon A, Epelbaum J. Somatostatinergic systems in brain: networks and functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viollet C, Vaillend C, Videau C, Bluet-Pajot MT, Ungerer A, L’Heritier A, Kopp C, Potier B, Billard J, Schaeffer J, Smith RG, Rohrer SP, Wilkinson H, Zheng H, Epelbaum J. Involvement of sst2 somatostatin receptor in locomotor, exploratory activity and emotional reactivity in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3761–3770. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachou S, Markou A. Intracranial self-stimulation: The use of the intracranial self-stimulation procedure in the investigation of reward and motivational processes: Effects of drugs of abuse. In: Olmstead MC, editor. Animal models of drug addiction. Human Press Inc; 2010. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Zeyda T, Diehl N, Paylor R, Brennan MB, Hochgeschwender U. Impairment in motor learning of somatostatin null mutant mice. Brain Res. 2001;906:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]