Abstract

Objectives

We studied associations of borderline and low-normal ankle brachial index (ABI) values with functional decline over five-year follow-up.

Background

Associations of borderline and low-normal ABI with functional decline are unknown.

Methods

The 666 participants included 412 with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Participants were categorized as follows: Severe PAD (ABI < 0.50), moderate PAD (ABI 0.50-0.69), mild PAD (ABI 0.70 to 0.89), borderline ABI (0.90 to 0.99), low normal ABI (1.00 to 1.09), and normal ABI (ABI 1.10-1.30). Outcomes were assessed annually for five years. Mobility loss was defined as loss of the ability to walk ¼ mile or walk up and down one flight of stairs without assistance among those without baseline mobility impairment. Becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously was defined as stopping during the six minute walk at follow-up among those who walked for six minutes continuously at baseline. Results adjust for age, sex, race, comorbidities, and other confounders.

Results

Hazard ratios (HR) for mobility loss according to ABI category were as follows. Severe PAD: HR=4.16 (95% Confidence Interval (CI)=1.58-10.92), moderate PAD: HR=3.82 (95% CI=1.66-8.81), mild PAD: HR=3.22 (95% CI=1.43-7.21), borderline ABI: HR=3.07 (95% CI=1.21-7.84), low normal ABI: HR=2.61 (95% CI=1.08-6.32) (p trend=0.0018). Similar associations were observed for becoming unable to walk six-minutes continuously (p trend<0.0001).

Conclusion

At five-year follow-up, persons with borderline ABI values have a higher incidence of mobility loss and becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously compared to persons with a normal baseline ABI. A low normal ABI is associated with an increased incidence of mobility loss compared to persons with a normal ABI.

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

We studied associations of borderline and low-normal ABI values with functional decline over five-year follow-up among 666 participants, including 412 with lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD). At five year follow-up, participants with borderline ABI values at baseline (ABI 0.90 to 0.99) had significantly greater mobility loss and were more likely to become unable to walk for six-minutes continuously compared to those with a normal baseline ABI. Participants with low normal ABI values (ABI 1.00 to 1.09) had significantly greater mobility loss compared to those with a normal baseline ABI.

Keywords: ankle brachial index, physical functioning, peripheral arterial disease, intermittent claudication

Eight million men and women in the United States have lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD). The prevalence of PAD is expected to increase as the population survives longer with chronic disease (1,2). PAD is common among patients age 50 and older in primary care medical practices and is frequently under-diagnosed (3,4). Among community dwelling populations, the prevalences of low-normal and borderline ABI values are similar to or higher than PAD (5,6). Persons with PAD, defined as an ankle brachial index (ABI) < 0.90, have greater functional impairment and faster rates of functional decline than persons without PAD (7,8). However, associations of borderline and low-normal ABI values with functional decline are unknown.

The ABI is a ratio of Doppler-recorded systolic pressures in the lower and upper extremities. In persons without PAD, arterial pressures increase with greater distance from the heart, because of increasing impedance with increasing arterial taper (9). This phenomenon results in higher systolic pressures at the ankle compared to the brachial arteries in persons without PAD. Thus, persons without lower extremity atherosclerosis have an ABI > 1.00. An ABI < 0.90 is highly sensitive and specific for angiographically-diagnosed PAD (10). However, recent data show that even persons with borderline ABI values (ABI 0.90 to 1.00) and low normal ABI values (ABI 1.01-1.10) have higher prevalences of subclinical atherosclerosis in the coronary and cerebrovascular arterial beds than persons with an ABI of 1.10 to 1.30 (5). Prevalences of intermittent claudication and atypical exertional leg pain are higher in persons with borderline ABI values than in those with ABI values of 1.10 and 1.40 (11). Thus, persons with borderline and low normal ABI values may experience higher rates of adverse outcomes than persons with ABI values of 1.10-1.30. However, associations of borderline and low-normal ABI values with functional decline are unknown.

In this prospective, observational study, we describe associations between baseline ABI values and annually measured functional outcomes, assessed up to five-years after baseline measures, in a large cohort of persons with and without PAD. We hypothesized that participants with low-normal and borderline baseline ABI values would have rates of functional decline that are less than participants with PAD but greater than persons with a normal ABI at baseline.

METHODS

Study Overview

The institutional review boards of Northwestern University and Catholic Health Partners Hospital approved the protocol. Participants gave written informed consent. The funding source for this study played no role in the design, conduct, reporting of the study, or decision to submit the manuscript.

Participants were part of the Walking and Leg Circulation Study (WALCS), a prospective, observational study designed to identify predictors of functional decline in persons with and without PAD (7,8,12). Participants underwent baseline assessment and returned annually for follow-up. Participants unable to return for follow-up were interviewed by telephone for the mobility outcome measure. Mean follow-up was 54 months.

Participant Identification

Participants with PAD were identified from among consecutive patients age 55 and older diagnosed with PAD in three Chicago-area non-invasive vascular laboratories (7,8). PAD participants were identified from among consecutive patients with PAD in the non-invasive vascular laboratory because this is an efficient method to identify large numbers of PAD participants with a wide range of PAD severity. Participants without PAD were identified from among persons with normal lower extremity arterial studies at the three non-invasive vascular laboratories and from among consecutive patients with appointments in a large general internal medicine practice at Northwestern. Identifying non-PAD participants from the non-invasive vascular laboratory allowed us to include non-PAD participants with a higher prevalence of leg symptoms and comorbidities who were relatively comparable to PAD participants except for the presence vs. absence of PAD. Identifying non-PAD participants from general medicine practice allowed us to include non-PAD participants more typical of the non-PAD patients encountered by practicing clinicians. Participants from general internal medicine who had a low ABI at their study visit were included among PAD participants. Exclusion criteria for the WALCS have been reported (7,8,12) and include dementia, recent major surgery, above or below knee amputations, nursing home residence, and wheelchair confinement. Non-English-speaking patients were excluded because investigators were not fluent in non-English languages. Individuals with PAD diagnosed in the non-invasive vascular laboratory were excluded if their baseline visit ABI was > 0.95. Similarly, persons whose non-invasive vascular laboratory testing showed no PAD were excluded if their ABI was ≤ 0.95 at their study visit. The ABI threshold was used because this is the ABI threshold used to define PAD in Northwestern’s non-invasive vascular laboratory. This exclusion criterion helped minimize mis-classification bias, for example in participants who may have had a low toe-brachial index in the non-invasive vascular laboratory but had a normal ABI at their study visit. Participants with baseline ABI > 1.30 were excluded from analyses. Participants with ABI > 1.30 have non-compressible lower extremity vessels and therefore could not be accurately classified into our ABI categories of interest (5,13).

Ankle Brachial Index Measurement

A hand-held Doppler probe (Nicolet Vascular Pocket Dop II; Nicolet Biomedical Inc, Golden, Colo) was used to obtain systolic pressures in the right and left brachial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries (7,8,14). Each pressure was measured twice. The ABI was calculated by dividing the mean of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pressures in each leg by the mean of the 4 brachial pressures (15). Zero values for the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were set to missing for the ABI calculation. Average brachial pressures in the arm with highest pressure were used when 1 brachial pressure was higher than the opposite brachial pressure in both measurement sets and the 2 brachial pressures differed by 10 mm Hg or more in at least one measurement set, since in such cases subclavian stenosis was possible (15). The lowest leg ABI was used in analyses. ABI categories were defined a priori as follows (5,8): ABI < 0.50 (severe PAD), ABI 0.50 to < 0.70 (moderate PAD), ABI 0.70 to < 0.90 (mild PAD), borderline PAD (ABI 0.90 to < 1.00), low normal ABI (ABI 1.00-1.10) and normal ABI (ABI 1.10-1.30). These ABI categorizations were defined based on prior study (5,8) and allowed us to assess associations of ABI with study outcomes across a wide range of ABI values.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome measures were mobility loss and becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously without stopping (8,12,16). These outcomes were assessed annually at each follow-up visit and were selected because they represent clearly defined, discrete endpoints. These outcomes avoid a possible “floor” effect that may occur with annual rates of distance achieved in the six-minute walk, for example, when a participant becomes unable to walk but cannot further deteriorate in functional performance. Secondary outcomes were a) a 15% decline in six-minute performance and b) a 20% decline in six-minute walk performance.

Six-minute walk

The six-minute walk was administered at baseline and at each annual follow-up visit. The six-minute walk test has excellent test re-test reliability in persons with PAD (17,18). Following a standardized protocol (7,8,12,17-19), participants walk up and down a 100-foot hallway for six minutes after instructions to cover as much distance as possible. The interviewer administering the test records whether the participant stopped during the six-minute walk. Participants who stopped at baseline were excluded from these analyses.

Mobility Measures

A critical factor in an older person’s ability to function independently in the community is mobility, defined as the ability to walk or climb stairs without assistance (16). Older people who lose mobility are less likely to remain in the community, have higher rates of morbidity, mortality, and hospitalizations and experience a poorer quality of life (16,19,20). Based on previous study, mobility loss was defined as becoming unable to walk up and down one flight of stairs or walk 1/4 mile without assistance among those without mobility impairment at baseline (20,21). At baseline and at each follow-up visit, participants were asked to indicate whether they were able to walk mile and whether they could climb up and down one flight of stairs a) on their own; b) with assistance; or c) not at all (20,21).

Comorbidities

Comorbidities assessed were diabetes, angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cancer, chronic lung disease, lower extremity arthritis, spinal stenosis, spinal disk disease, and stroke. Disease-specific algorithms that combine data from patient report, medical record review, medications, laboratory values, and a questionnaire completed by the participant’s primary care physician were used to verify and document baseline comorbidities other than knee and hip arthritis, based on criteria previously developed (22). American College of Rheumatology criteria were used to document presence of knee and hip osteoarthritis (23,24).

Other Measures

Height and weight were measured at the study visit. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kilograms)/(height (meters))2. Cigarette smoking history was determined with patient report. At baseline, participants were asked to report the number of blocks they walked during the previous week. At each follow-up visit, we used patient report, a primary care physician questionnaire, and medical record review to identify lower extremity revascularizations each year.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of participants in each ABI category were compared using general linear models for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Functional outcomes were a) mobility loss among participants without mobility impairment at baseline and b) loss of the ability to walk continuously for six minutes without stopping among participants who completed the six-minute walk test without stopping at baseline. Secondary functional outcome measures were 15% and 20% declines, respectively, in six-minute walk performance. Cox regression analyses were used to compare rates of each functional outcome across ABI categories, adjusting for age, sex, race, and baseline values for comorbidities, smoking, body mass index, and patient-reported blocks walked during the prior week. ABI categories were entered as dummy variables into the regression analyses. Participants who met our primary outcome definitions at baseline (mobility impairment or inability to walk for six-minutes without stopping) were excluded from these respective analyses. Person-time was calculated as the number of months from the baseline visit to the date of the most recent visit (last seen) or the date of the visit during which each functional outcome of interest was first reported, whichever came first. Participants who died before experiencing an outcome measure or underwent lower extremity revascularization during follow-up were censored at the date of their last visit prior to these events. These analyses were repeated in which death was considered as an outcome if it occurred before mobility loss or stopping during the six-minute walk, respectively. Because lower extremity arthritis and spinal disk disease may influence rates of functional decline, Cox regression analyses were repeated within the subset of participants with no history of knee arthritis, hip arthritis, disk disease, or spinal stenosis. We also tested for interactions between the presence vs. absence of knee arthritis, hip arthritis, spinal disk disease, or spinal stenosis and the association of the ABI with functional outcomes.

We tested the proportional hazards assumption for mobility loss and the stop during the six-minute walk analyses using martingale residuals based methods, and we did not find any significant deviation from the proportional hazards assumption (25). Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of 731 men and women who completed baseline testing for WALCS and had a baseline ABI < 1.30, 698 (95%) completed at least one follow-up visit. Of these, 18 underwent lower extremity revascularization prior to their first annual follow-up visit, leaving 680 participants. Of these, 516 (284 with PAD) completed the six-minute walk test at baseline without stopping and participated in at least one annual follow-up six-minute walk test. These 516 participants were included in analyses of becoming unable to walk for six minutes without stopping. The corresponding number of participants who were free of mobility impairment at baseline was 647. A total of 666 participants (412 with PAD) met criteria for inclusion in either the six-minute walk or mobility loss analyses.

Table 1 shows characteristics associated with each ABI category at baseline among the 666 participants. Lower ABI values were associated with older age, lower BMI, greater pack-years of cigarette smoking, higher prevalences of diabetes and history of cardiac or cerebrovascular diseases, lower prevalences of lower extremity arthritis or spinal disk disease, and fewer blocks walked during the previous week.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants According to Baseline Ankle Brachial Index Category (n=666).

| ABI<0.5 (N=61) | ABI 0.50-0.69 (N=178) | ABI 0.70-0.89 (N=173) | ABI 0.90-0.99 (N=62) | ABI 1.00-1.09 (N=78) | ABI 1.10-1.30 (N=114) | P-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 74.07 ± 8.95 | 71.66 ± 8.68 | 71.19 ± 7.99 | 71.60 ± 8.83 | 70.74 ± 7.90 | 66.71 ± 7.11 | <.0001 |

| Male Sex (%) | 49.18 | 62.92 | 58.96 | 46.77 | 38.46 | 65.79 | 0.7863 |

| African-American Race (%) | 22.95 | 15.73 | 13.29 | 17.74 | 25.64 | 13.16 | 0.8298 |

| Ankle brachial index | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 1.06 ± 0.03 | 1.17 ± 0.05 | <.0001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.37 ± 4.74 | 26.76 ± 4.85 | 28.11 ± 4.72 | 28.28 ± 4.94 | 27.63 ± 5.23 | 28.30 ± 4.84 | 0.012 |

| Cigarette smoking (pack-years) | 32.78 ± 31.13 | 36.24 ± 32.7 | 40.11 ± 35.26 | 26.26 ± 28.83 | 15.67 ± 21.79 | 20.89 ± 30.77 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 27.87 | 34.83 | 28.90 | 24.19 | 12.82 | 20.18 | 0.0009 |

| Cardiac or cerebrovascular disease (%) | 59.02 | 62.92 | 53.76 | 41.94 | 30.77 | 35.96 | <.0001 |

| Pulmonary disease (%) | 26.23 | 25.84 | 36.42 | 29.03 | 38.46 | 35.09 | 0.0573 |

| Cancer (%) | 11.48 | 11.80 | 17.92 | 22.58 | 12.82 | 14.04 | 0.5715 |

| Lower extremity arthritis, disk disease, or spinal stenosis | 31.15 | 39.89 | 39.88 | 56.45 | 60.26 | 53.51 | <.0001 |

| Number of blocks walked during the past week. | 22.64 ± 33.93 | 41.53 ± 72.6 | 33.46 ± 45.92 | 43.27 ± 55.49 | 48.77 ± 55.75 | 56.79 ± 64.5 | 0.003 |

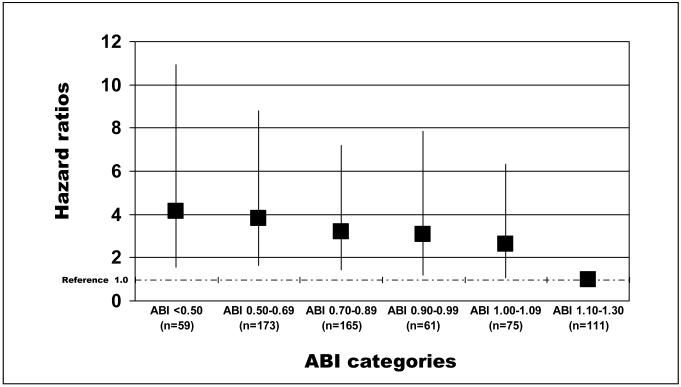

Figure 1 shows adjusted associations of baseline ABI levels with incident mobility loss among participants without mobility impairment at baseline. Adjusting for age, sex, race, comorbidities, smoking, BMI, and physical activity level, lower ABI values were associated with significantly higher rates of mobility loss (p trend = 0.0018). Compared to participants with a normal baseline ABI, those with a baseline ABI < 0.50 had a significantly increased risk of mobility loss (p=0.0038) during annual follow-up visits up to five-years after baseline (Figure 1). Compared to the reference category with normal baseline ABI, increased rates of mobility loss were observed among participants with ABI 0.50-0.70 (p=0.0016), ABI 0.70 to 0.90 (p=0.0046), ABI 0.90 to 1.00 (p=0.0187), and ABI 1.00-1.10 (p=0.033), adjusting for confounders (Figure 1). No significant interactions were observed between presence vs. absence of knee arthritis, hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, or spinal disk disease and the association of the ABI with mobility loss (data not shown). Results were not substantially changed when deaths occurring prior to mobility loss were included as outcomes (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Adjusted associations of baseline ankle brachial index and mobility loss at five year follow-up among persons age 55 and older (n=631)

Results are adjusted for age, sex, race, comorbidities, body mass index, smoking, and physical activity levels. The ‘y’ axis shows the hazard ratio representing the risk of mobility loss at five year follow-up. Number of events per ankle brachial index (ABI) category: ABI <0.50: 12; ABI 0.50-0.69: 30; ABI 0.70-0.89: 30; ABI 0.90-99: 11; ABI 1.00-1.09: 16; ABI 1.10-1.30: 8. Number of deaths per ankle brachial index (ABI) category: ABI <0.50: 20; ABI 0.50-0.69: 39; ABI 0.70-0.89: 28; ABI 0.90-99: 8; ABI 1.00-1.09: 9; ABI 1.10-1.30: 10.

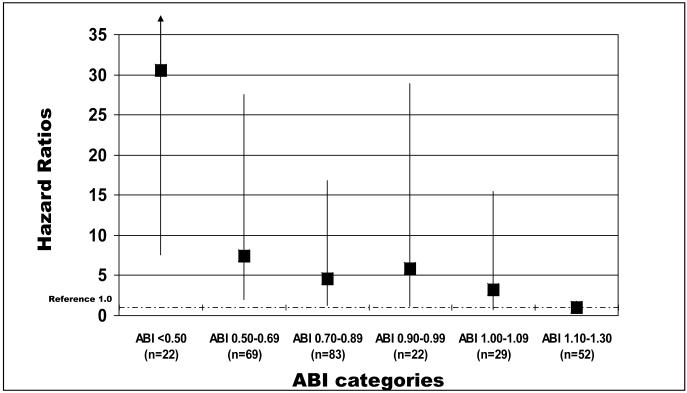

Adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking, comorbidities, body mass index, and physical activity level, a significant interaction was observed between presence vs. absence of knee arthritis, hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, or spinal disk disease and the association of the ABI with stopping during the six-minute walk test (p value for interaction term = 0.023). In this interaction, associations of ABI with becoming unable to walk continuously for six-minutes were not significant among participants with history of knee or hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, or spinal disk disease (data not shown). In contrast, lower ABI values were associated with increased risk of becoming unable to walk continuously for six-minutes among participants without history of knee or hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, or spinal disk disease (p trend < 0.001, Figure 2). Among participants without history of knee or hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, or spinal disk disease, compared to the reference group with ABI of 1.10-1.30 at baseline, borderline PAD (ABI 0.90-0.99) was associated with increased risk of becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously without stopping (HR = 5.88, 95% CI = 1.20-28.89, p=0.029) (Figure 2). Compared to the reference group, a low normal ABI at baseline (ABI 1.00-1.10) was associated with increased risk of becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously (HR = 3.26, 95% CI = 0.69-15.45, p=0.14), but findings were not statistically significant (Figure 2). Results were not substantially changed when analyses were repeated in which deaths occurring prior to a participant stopping during the six-minute walk were included as an outcome. However, in these additional analyses the association of borderline ABI with becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously did not reach statistical significance (HR=1.77, 95% CI=0.93-3.36, p=0.08).

Figure 2.

Adjusted associations of baseline ankle brachial index and loss of the ability to walk continuously for six minutes at five year follow-up among persons age 55 and older (n=276).

Results are adjusted for age, sex, race, comorbidities, body mass index, smoking, and physical activity levels. The ‘y’ axis shows the hazard ratio representing risk of becoming unable to walk continuously for six minutes at five year follow-up. Excludes participants with knee arthritis, hip arthritis, spinal stenosis, and disk disease because of a significant interaction between the presence vs. absence of lower extremity arthritis and spinal disk disease and the association of the ankle brachial index with becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously. ABI <0.50: 12; ABI 0.50-0.69: 19; ABI 0.70-0.89: 15; ABI 0.90-99: 4; ABI 1.00-1.09: 4; ABI 1.10-1.30: 3

Number of deaths per ABI category: ABI <0.50: 4; ABI 0.50-0.69: 21; ABI 0.70-0.89: 28; ABI 0.90-99: 8; ABI 1.00-1.09: 9; ABI 1.10-1.30: 10.

Adjusting for age, sex, race, smoking, comorbidities, body mass index, and physical activity level and compared to the reference group with a normal baseline ABI, borderline and low normal ABI values were not associated significantly with higher risk of experiencing a 15% or greater decline in six-minute walk performance or with higher risk of experiencing a 20% or greater decline in six-minute walk performance (data not shown).

Participants with ABI 1.10-1.30 were significantly less likely to develop an ABI < 0.90 during follow-up compared to those with baseline ABI of 0.90-0.99 and those with baseline ABI 1.00-1.09 (Table 2). We therefore repeated analyses in Figures 1 and 2 with additional adjustment for change in ABI during follow-up. Associations of borderline and low normal ABI values with mobility loss and becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously were attenuated or no longer statistically significant after this additional adjustment (data not shown).

Table 2. Associations of Baseline Ankle Brachial Index Category with Incident Peripheral Arterial Disease among Participants with a Baseline Ankle Brachial Index of 1.00-1.30*.

| ABI category | Number of participants at baseline | Number of events | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Pairwise P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABI 0.90-0.99 | 62 | 31 | 1.0 (reference) | Not Applicable |

| ABI 1.00-1.09 | 77 | 13 | 0.22 (0.11-0.43) | <0.001 |

| ABI 1.10-1.30 | 111 | 2 | 0.02 (0.00-0.09) | <0.001 |

Data adjust for age, sex, race, comorbidities, smoking, and body mass index.

DISCUSSION

Data presented here show that among 666 men and women with and without PAD, those with borderline ABI values of 0.90 to 0.99 had significantly higher rates of mobility loss and significantly higher rates of becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously at five year follow-up, compared to persons with a normal baseline ABI of 1.10-1.30. In addition, participants with low normal ABI values of 1.00-1.09 had significantly higher rates of mobility loss at five-year follow-up, compared to persons with a normal baseline ABI. These findings are important because the ABI threshold typically considered clinically important is ABI < 0.90. However, data presented here demonstrate that even ABI values of 0.90-1.09 are associated with higher rates of functional outcomes compared to ABI values of 1.10-1.30.

An ABI < 0.90 is highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing PAD, compared to lower extremity angiography (10). However, because of increasing impedance with increasing arterial taper, systolic pressures normally increase with greater distance from the heart. Thus, a truly normal ABI is > 1.00 (9). Our finding that persons with low normal and borderline ABI values have higher rates of functional decline for some outcomes is consistent with prior studies showing higher prevalences of subclinical atherosclerosis and mortality in persons with low normal and borderline ABI values (5,13).

In contrast to our findings for mobility loss and loss of the ability to walk for six-minutes continuously, we found no significant associations of borderline or low normal ABI values with a 15% or 20% decline in six-minute walk performance during five-year follow-up. Reasons for these discrepancies across our outcome measures are not clear. However, it is possible that becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously during follow-up is a more specific outcome for walking impairment related to lower extremity ischemia than the outcomes of 15% or 20% decline in six-minute walk performance. Participants with borderline or low normal ABI values who slow their six-minute walking speed sufficiently to experience 15% or 20% declines in six-minute walk performance but do not stop during the six-minute walk at follow-up may be experiencing walking disability due to comorbidities other than leg ischemia.

The mechanism of higher rates of becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously and/or mobility loss at five-year follow-up among persons with low normal and borderline ABI values at baseline cannot be discerned from data presented here. Several mechanisms are possible. First, our results show that participants with low normal and borderline ABI values are more likely to progress to an ABI < 0.90 during five-year follow-up than participants with normal baseline ABI values. Our findings suggest that a higher rate of progression of lower extremity atherosclerosis among participants with low-normal and borderline ABI values is a plausible causal pathway for findings reported here. Alternatively, low-normal and borderline ABI values may be markers for other characteristics associated with higher rates of functional decline, such as presence of atherosclerosis in other arterial beds (5).

It is not clear from our data why an interaction with presence of knee arthritis, hip arthritis, disk disease, or spinal stenosis was present for the association of baseline ABI with the inability to walk continuously for six-minutes at follow-up, while no such interaction was observed for the association of baseline ABI with mobility loss. Differences in these associations relate to the fact that the six-minute walk test is an objective measure, and possibly a more accurate measure of actual performance, while the mobility loss outcome is subjective. Alternatively, knee or hip arthritis and/or disk disease may affect performance on the six minute walk to a greater degree than mobility.

This study has limitations. Participants were identified from academic medical centers, and it is unclear whether our findings are generalizable to individuals outside of academic medical centers. Second, by necessity, participants with mobility impairment at baseline and those unable to walk for six-minutes continuously at baseline were excluded from analyses of mobility loss and incident inability to walk for six minutes continuously at follow-up, respectively. Thus, this study does not assess functional changes in these excluded persons. Third, unmeasured variables may account for associations of borderline and low normal ABI values with functional decline in persons with PAD. Fourth, despite careful identification and confirmation of comorbidities and adjustment for comorbidities in our analyses, we cannot rule out the possibility that comorbidities associated with low normal and borderline ABI values may contribute to findings reported here. Fifth, the relatively small number of events for becoming unable to walk for six minutes continuously limits statistical power. Finally, our results do not include data for disease-specific health related quality of life measures.

In conclusion, at five year follow up, persons with borderline and low normal ABI values are at higher risk for mobility loss compared to persons without PAD. Participants with borderline ABI values are also at higher risk for becoming unable to walk for six-minutes continuously at five-year follow-up. Further study is needed to confirm the findings reported here and to determine whether interventions such as exercise can prevent functional decline in persons with a borderline or low normal ABI.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by grants #R01-HL58099, R01-HL64739, R01-HL071223, and R01-HL076298 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and by grant #RR-00048 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH. Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ABI

ankle brachial index

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- WALCS

Walking and Leg Circulation Study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures. None

Conflicts of Interest. None

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosamand W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics- 2007 update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115(5):e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison MA, Hoe E, Denenberg JO, et al. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott MM, Kerwin DR, Liu K, et al. Prevalence and significance of unrecognized lower extremity peripheral arterial disease in general medicine practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Jun;16(6):384–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDermott MM, Liu K, Criqui MH, et al. Ankle-brachial index and subclinical cardiac and carotid disease: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:33–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, et al. Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 1993;88:837–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. Leg symptoms commonly reported by men and women with lower extremity peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286:1599–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.13.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, et al. The ankle brachial index as a measure of leg functioning and physical activity in peripheral arterial disease: the walking and leg circulation study. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:873–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-12-200206180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung YC. Biodynamics - Circulation. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1984. Blood flow in arteries: pressure and velocity waves in large arteries and the effects of geometric nonuniformity; pp. 133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lijmer JG, Hunink MG, van den Dungen JJ, Loonstra J, Smit AJ. ROC analysis of non-invasive tests for peripheral arterial disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1996;22:391–8. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(96)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JC, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Golomb BA, Fronek A. Exertional leg pain in patients with and without peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2005;112:3501–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA. 2004;292:453–461. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnick HE, Lindsay RS, McDermott MM, et al. Relationship of high and low ankle brachial index to all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109:733–739. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112642.63927.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Liu K, et al. The lower ankle brachial index calculated by averaging the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arterial pressures is most closely associated with leg functioning in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:1164–1171. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.108640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shadman R, Criqui MH, Bundens WP, et al. Subclavian artery stenosis: prevalence, risk factors, and association with cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel KV, Coppin AK, Manini TM, et al. Midlife physical activity and mobility in older age. The InCHIANTI study. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery PS, Gardner AW. The clinical utility of a six-minute walk test in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:706–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Ferrucci L, et al. Obesity, weight change, and functional decline in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The six-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:919–923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick E, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower extremity function in persons over 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, et al. The Women’s Health and Aging Study: health and social characteristics of older women with disability. National Institute on Aging; Bethesda, MD: 1995. NIH publication 95-4009, Appendix E. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:505–514. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale residuals. Biometrika. 1993;80:557–572. [Google Scholar]