Abstract

This study explored baseline levels of knowledge and attitude toward genetic testing (GT) for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer among Puerto Rican women. A secondary aim was to evaluate whether these factors differed between respondents in Puerto Rico and Tampa. Puerto Rican women with a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer who live in Puerto Rico (n = 25) and Tampa (n = 20) were interviewed. Both groups were interested in obtaining GT; women living in Puerto Rico were more likely to report they would get GT within 6 months (p = 0.005). The most commonly cited barrier was cost; the most commonly cited facilitator was provider recommendation. There was no difference in overall knowledge between Tampa (M = 5.15, SD = 1.63) and Puerto Rico (M = 5.00, SD = 1.87) participants (p = 0.78). Involving health care providers in recruitment and highlighting that GT may be available at minimal or no cost in the USA and Puerto Rico may facilitate participation.

Keywords: Genetic counseling, Genetic testing, Hereditary cancer, Hispanic, Puerto Rico

Introduction

The majority of hereditary breast cancers are associated with mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) tumor suppressor genes (Miki et al. 1994; Wooster et al. 1995). A recent study of cancer risks in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers in a large US-based sample estimated the cumulative breast cancer risk at age 70 years to be 46% in BRCA1 carriers and 43% in BRCA2 carriers. Cumulative ovarian cancer risk was 39% in BRCA1 carriers and 22% in BRCA2 carriers (Chen et al. 2006). Additionally, BRCA mutation carriers have a 40–60% lifetime risk for a second primary breast cancer (Ford et al. 1994; Metcalfe et al. 2004; Robson et al. 2005).

Several recent studies have documented the presence of BRCA mutations in Hispanic women (Mullineaux et al. 2003; Weitzel et al. 2005, 2007). A population-based study from the Northern California Cancer Registry reported that Hispanic women with a personal history of breast cancer have the highest prevalence of BRCA1 mutations compared to other racial/ethnic minority groups (i.e., African American, Asian American) in the USA (John et al. 2007). However, existing studies in the USA documenting BRCA mutation prevalence in Hispanic populations were based on participants that were predominantly of Mexican origin (Mullineaux et al. 2003; Weitzel et al. 2005, 2007).

In the USA, the term “Hispanic” refers to a heterogeneous group that shares a common language and some sociocultural markers. Although most Hispanic populations are expected to be a mix of three ancestral populations (African, European, and Native American), the relative proportion of each ancestral genetic background has been shown to vary within and across Hispanic populations (Gonzalez Burchard et al. 2005). Previous studies using ancestry informative markers have shown that Puerto Ricans carry more European and African ancestry, but significantly less Native American ancestry compared to Mexicans (Salari et al. 2005). Given those differences, it is important to evaluate the prevalence and penetrance of BRCA mutations by subethnicity.

BRCA founder mutations, a defined set of recurrent mutations in genetically similar populations with a common ancestry, have been identified in several populations, including in Hispanics from California (Weitzel et al. 2005). The presence of founder mutations has allowed the development of simplified screening panels for initial mutation screening, thereby providing a cost-effective approach to genetic testing (GT) for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC). In a retrospective study of 23 female breast cancer patients undergoing GT for BRCA mutations in the highest volume breast surgery practices in San Juan, Puerto Rico, a total of 11 different deleterious mutations were observed, including two mutations in BRCA1 and nine mutations in BRCA2. Three recurrent mutations (BRCA1 del exon1-2, BRCA2 4150G>T, and BRCA2 6027del4) accounted for over 70% of all the BRCA mutations observed in this study population (J. Dutil, personal communication). However, these findings must be confirmed in larger cohorts of Puerto Rican women. As such, researchers may recruit women from US cities with large Puerto Rican populations, such as Tampa, Florida; the island of Puerto Rico; or both locations, to participate in these studies.

The cancer risks, available risk management strategies including chemoprevention, surgery, and surveillance available both in the USA and Puerto Rico, as well as the risks to family members make it clinically and ethically imperative that patients who may participate in these studies are aware of the implications of participating in testing. Thus, active patient recruitment and the provision of pre- and post-test genetic counseling will likely be necessary in the context of a research protocol. Even in studies that conduct mutation testing on archived samples, follow-up notification and counseling for patients who test positive may still be required. Therefore, informing patients about HBOC and GT is a critical component to an effective study design.

Given the greater availability of clinical BRCA testing, exposure to media coverage, and advertisements related to HBOC and BRCA testing in the USA (Jacobellis et al. 2004; Mouchawar et al. 2005a, b) compared to Puerto Rico, there may be differences by location related to knowledge and interest in GT that may impact recruitment and education efforts in these locations. The purposes of the current pilot study were to explore baseline levels of knowledge, cultural factors, attitudes toward, and interest in GT and to evaluate whether these factors differed between Puerto Rican women who live in Puerto Rico and Tampa, Florida. These data will be used to develop and refine targeted recruitment approaches and counseling protocols for a future research study to establish the prevalence and penetrance of BRCA mutations in Puerto Rican populations.

Materials and methods

Overall study context

The geographic proximity and large Hispanic populations in Puerto Rico and Florida have laid an important foundation for the development of an academic partnership between the Ponce School of Medicine (PSM) in Puerto Rico and Moffitt Cancer Center (MCC) in Tampa. Through an NCI-funded cooperative agreement, the PSM–MCC Partnership is a collaboration between a minority-serving institution (PSM) and an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center (MCC) to address cancer-related health disparities among Hispanics. The Tampa-based team of the MCC had an existing study to identify differences in knowledge and attitudes toward HBOC and GT in a multiethnic sample of Hispanic women in Tampa (Quinn et al. 2011; Vadaparampil et al. 2010a, b). The Puerto Rico-based team of the PSM is conducting a study aimed at identifying the prevalent BRCA mutations in Puerto Rico and at evaluating available models of carrier risk assessment in this population. Based on these mutual interests, a sample of women were recruited from Puerto Rico and compared with the subsample of Puerto Rican participants from the multiethnic study of Hispanics in Tampa (Quinn et al. 2011; Vadaparampil et al. 2010a, b). The information collected in this project was intended to inform future population-based studies to better define the prevalence and penetrance of BRCA mutations specific to Puerto Rico.

Design and setting

Eligible consenting individuals participated in a semi-structured in-depth qualitative interview followed by a series of structured quantitative survey items for descriptive and exploratory purposes. Therefore, the sample size (n = 45) was based on estimates of the number needed for exploratory qualitative interviews (Guest et al. 2005; Kvale 1996), rather than statistical power calculations. The current study presents only the quantitative data. Participants were recruited after the project received appropriate institutional review board approvals in both Tampa and Puerto Rico, and each participant provided written informed consent prior to participation. Data collection took place between May 2006–September 2008 in Tampa participants and June and July of 2008 in Puerto Rico.

Participant recruitment and data collection

The overall recruitment methods in Puerto Rico and Tampa were similar and summarized below. Additional details about the recruitment and results for the Puerto Rico- (August et al. 2011) and Tampa-based (Quinn et al. 2011; Vadaparampil et al. 2010a, b) samples can be found in additional reports. Eligible participants were Hispanic women who: (a) were between 21 and 65 years old, (b) resided in Puerto Rico or Tampa, (c) had a personal diagnosis of breast cancer at ≤age 50 or ovarian cancer at any age or had at least one first-degree relative (FDR; mother, sister, daughter) diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50 or at least one FDR diagnosed with ovarian cancer at any age, (d) self-identified as Puerto Rican, and (e) had not previously had genetic counseling and/or GT for hereditary cancer. Participants were recruited by a team of bilingual–bicultural trained research assistants using community-based outreach methods (e.g., attending cancer support groups) and distribution of a flyer with a brief description and purpose of the study, basic eligibility criteria, and a telephone number for prospective participants to call with questions or to express interest in the study. Eligible, consenting individuals were interviewed in person. The interview and survey items required 45–90 min in total to complete. At the end of the interview, participants received a $25 honorarium.

Measures

Our primary outcome variable was interest in GT. This was assessed by providing a brief description of GT: “Among men and women with a strong family history of certain cancers such as breast and ovarian cancer, genetic testing has become available to identify those at higher risk of developing these specific cancers.” Participants were then asked to rate how strongly they agreed with the statement that they would be likely to have GT in the next 6 months if it were available to them. Table 1 provides a brief summary of several cultural, knowledge, and attitudinal factors of interest. We also evaluated the following sociodemographic and medical characteristics via a self-report questionnaire: age, marital status, have children, education, employment status, religion, income, personal history of breast cancer before age 50, personal history of ovarian cancer at any age, FDR (i.e., mother, sister, or daughter) with breast cancer before age 50, and FDR (i.e., mother, sister, or daughter) with ovarian cancer at any age.

Table 1.

Summary of measures

| Measure | Description | Response options | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural factors | Birthplace in USA | Yes, no | N/A |

| 8-Item scale of language preference from the Year 2000 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). (Berrigan et al. 2006; Vadaparampil et al. 2006) | 5-Point scale with categories: “Only Spanish,” “More Spanish than English,” “Spanish and English about the same,” “More English than Spanish,” and “Only English” | Summed scores; 8–13 = low English language preference, 14–27 = medium English language preference, and 28–40 = high English language preference (Cronbach's alpha = 0.96) | |

| Fatalism—the belief that death is inevitable when cancer is present | 15-Item Powe Fatalism Inventory (PFI). Based on the philosophic origins and attributes of cancer fatalism: fear, predetermination, pessimism, and inevitable death. (Powe 1996) | Yes, no | One point is added to the final score for each yes response given by the participant, and higher scores indicate higher levels of fatalism (Powe and Weinrich 1999) (Cronbach's alpha = 0.62) |

| Familism—the cultural value that reflects an individual's strong identification and attachment with his or her nuclear and extended families | 18-Item Familism Scale. Addresses four dimensions of familism, including familial support, familial interconnectedness, familial honor, and subjugation of self for family (Steidel and Contreras 2003) | 10-Point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree) | A score for each subscale, as well as an overall AFS score, can be calculated by the mean for each subscale or the whole scale (for overall score) (Cronbach's alpha = 0.90) |

| Knowledge | 11-Item Knowledge Scale. Measures four aspects of HBOC genetics knowledge: (1) prevalence of BRCA gene mutations, (2) patterns of inheritance, (3) cancer risks associated with BRCA mutations, and (4) risk management options for women with a BRCA mutation. (Hopwood et al. 2001; Lerman et al. 1997a; Lerman et al. 1996; Lerman et al. 1997b) | Yes, no, don't know | All items were scored as a 1 if the respondent provided the correct answer and a 0 if they gave an incorrect or “don't know” response. This allowed for the calculation of an overall knowledge score that could range from 0 to 11 |

| Attitude towards GT | 8-Items measuring GT barriers and facilitators. (Peters et al. 2006; Vadaparampil et al. 2007) | 5-Point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) | Each item considered individually |

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS® v. 9.1 software (SAS Institute 2003). All tests were two sided with a statistical significance level set at p ≤ 0.05. For the items related to attitudes toward GT, responses were collapsed into two categories: (1) those who responded “strongly agree” or “agree,” and (2) those who responded “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” or “don't know.” The 11 knowledge items were summed to create a composite knowledge score (range, 0–11). An independent samples t test or analysis of variance was used to compare composite knowledge among the responses given for the demographic and clinical characteristics. Because a goal of this study was to identify baseline levels of knowledge about various aspects of HBOC and GT that may be addressed either during recruitment or participant counseling (e.g., prevalence, risk factors, and inheritance), we conducted comparisons between locations (Puerto Rico and Tampa) and knowledge (correct response or incorrect/don't know) using a chi-square test of homogeneity for each of the knowledge items. In instances where the cell count was ≤5, a Fisher's exact test was conducted. We used a similar approach to evaluate attitude toward GT by location. An independent samples t test was conducted to compare composite knowledge by location. No multiple comparison adjustments were considered due to the exploratory nature of this study.

Results

Demographic, clinical, and cultural characteristics of the study population

Of the 45 individuals who participated in this study, 25 were from Puerto Rico, and 20 were from Tampa. As shown in Table 2, most participants were aged 31–50 (44%) or older than 50 (42%). Most participants were married (60%), had children (82%), employed full or part time (60%), and Catholic (67%). The largest proportion had a college education (40%) and income ≤$20,000 (38%) relative to other educational attainment and income levels. Additionally, most participants (80%) were born in Puerto Rico. The only statistically significant difference in sociodemographic characteristics by participant location was that of income, such that participants from Puerto Rico reported lower income (p = 0.01). Regarding personal cancer history, 36% reported a breast cancer diagnosis before age 50, and 9% reported a history of ovarian cancer. With respect to FDR cancer history, 31% reported having an FDR diagnosed with breast cancer before age 50, and 4% had an FDR with a history of ovarian cancer.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic, medical, and cultural characteristics by location (n = 45)

| Total (n = 45) n (%) | Tampa (n = 20) n (%)a | Puerto Rico (n = 25) n (%) | p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | 0.50 | |||

| ≤30 | 6 (13.33) | 4 (20.00) | 2 (8.00) | |

| 31–50 | 20 (44.44) | 9 (45.00) | 11 (44.00) | |

| >50 | 19 (42.22) | 7 (35.00) | 12 (48.00) | |

| Marital status | 0.54 | |||

| Married/Living with partner | 27 (60.00) | 13 (65.00) | 14 (56.00) | |

| Single/Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 18 (40.00) | 7 (35.00) | 11 (44.00) | |

| Have children | 0.43 | |||

| Yes | 37 (82.22) | 18 (90.00) | 19 (76.00) | |

| No | 7 (15.56) | 2 (10.00) | 5 (20.00) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.22) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.00) | |

| Education | 0.83 | |||

| <High school | 5 (11.11) | 3 (15.00) | 2 (8.00) | |

| High school | 11 (24.44) | 4 (20.00) | 7 (28.00) | |

| Some college | 10 (22.22) | 5 (25.00) | 5 (20.00) | |

| College | 18 (40.00) | 8 (40.00) | 10 (40.00) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.22) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (4.00) | |

| Employment status | 0.22 | |||

| Full or part time | 27 (60.00) | 10 (50.00) | 17 (68.00) | |

| Unemployed/Seasonal/Homemaker | 18 (40.00) | 10 (50.00) | 8 (32.00) | |

| Religion | 0.78 | |||

| Catholic | 30 (66.67) | 12 (60.00) | 18 (72.00) | |

| Christian | 3 (6.67) | 2 (10.00) | 1 (4.00) | |

| Other | 11 (24.44) | 5 (25.00) | 6 (24.00) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.22) | 1 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Income | 0.01* | |||

| ≤$20,000 | 17 (37.78) | 4 (20.00) | 13 (52.00) | |

| $20,001–$40,000 | 14 (31.11) | 5 (25.00) | 9 (36.00) | |

| >$40,000 | 11 (24.44) | 8 (40.00) | 3 (12.00) | |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (6.67) | 3 (15.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Medical characteristics | ||||

| Personal history of breast cancer <age 50 | 0.05 | |||

| Yes | 16 (35.56) | 4 (20.00) | 12 (48.00) | |

| No | 29 (64.44) | 16 (80.00) | 13 (52.00) | |

| Personal history of ovarian cancer | 0.61 | |||

| Yes | 4 (8.89) | 1 (5.00) | 3 (12.00) | |

| No | 39 (86.67) | 19 (95.00) | 20 (80.00) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.44) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.00) | |

| First-degree relative had breast cancer <age 50 | 0.67 | |||

| Yes | 14 (31.11) | 6 (30.00) | 8 (32.00) | |

| No | 24 (53.33) | 12 (60.00) | 12 (48.00) | |

| Missing | 7 (15.56) | 2 (10.00) | 5 (20.00) | |

| First-degree relative had ovarian cancer | 0.23 | |||

| Yes | 2 (4.44) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.00) | |

| No | 31 (68.89) | 17 (85.00) | 14 (56.00) | |

| Missing | 12 (26.67) | 3 (15.00) | 9 (36.00) | |

| Cultural characteristics | ||||

| Born in mainland USA | 0.06 | |||

| Yes | 9 (20.00) | 7 (35.00) | 2 (8.00) | |

| No | 36 (80.00) | 13 (65.00) | 23 (92.00) | |

| Language preference | 0.01* | |||

| Low English preference | 14 (31.11) | 4 (20.00) | 10 (40.00) | |

| Medium English preference | 15 (33.33) | 4 (20.00) | 11 (44.00) | |

| High English preference | 16 (35.56) | 12 (60.00) | 4 (16.00) | |

| Mean ± SD | pc | |||

| Fatalism | ||||

| Fatalism score | 5.18 ± 2.61 | 4.95 ± 2.78 | 5.36 ± 2.51 | 0.61 |

| Familism | ||||

| Overall score | 3.88 ± 0.73 | 3.75 ± 0.77 | 3.99 ± 0.68 | 0.27 |

| Familial support | 4.03 ± 0.75 | 3.81 ± 0.78 | 4.20 ± 0.70 | 0.08 |

| Familial interconnectedness | 4.63 ± 0.85 | 4.54 ± 0.91 | 4.70 ± 0.80 | 0.52 |

| Familial honor | 3.03 ± 0.97 | 2.95 ± 0.90 | 3.09 ± 1.03 | 0.63 |

| Subjugation of self for family | 3.50 ± 1.22 | 3.39 ± 1.39 | 3.59 ± 1.08 | 0.60 |

*p < 0.05

aPercentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding error

bχ2 tests of homogeneity used to compare groups; Fisher's exact test used for variables with ≤5 in each cell. Kruskal–Wallis test used to compare groups for language preference

cIndependent samples t test used to compare groups

Regarding cultural characteristics, most participants were not born in the mainland USA (80%). Respondents were evenly grouped into low, medium, and high groups for English language preference. Compared to Tampa participants, participants from Puerto Rico reported low or medium English language preference. The only cultural characteristic that differed significantly between Puerto Rico and Tampa participants was language preference (p = 0.01). The average fatalism score for all participants was 5.18 (SD = 2.61). Regarding familism scores, the average scores were as follows: 3.88 (SD = 0.73) overall, 4.03 (SD = 0.75) for familial support, 4.63 (SD = 0.85) for familial interconnectedness, 3.03 (SD = 0.97) for familial honor, and 3.50 (SD = 1.22) for subjugation of self for family.

Interest in GT by location

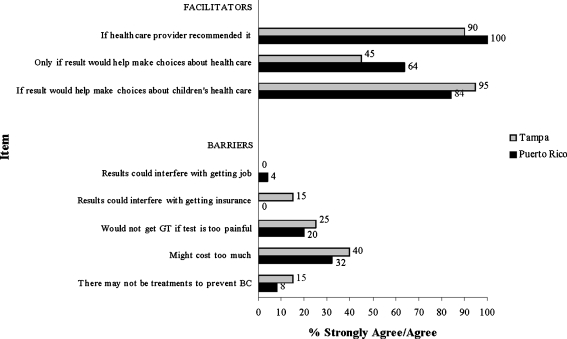

Results from Fisher's exact test indicated a significant difference between location and reporting that one would get GT within the next 6 months (p = 0.005), with respondents from Puerto Rico more frequently reporting agreement (i.e., strongly agree or agree) with this statement than those from Tampa. Figure 1 presents responses to three items measuring facilitators related to GT and five items measuring barriers related to GT by participant location. Comparisons for each item by location were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). In general, more participants reported they strongly agreed or agreed with the positive attitudinal items compared to the negative attitudinal items.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of facilitators and barriers to GT by location

Knowledge about hereditary cancer by location

Table 3 presents frequencies and percentages of correct responses for each knowledge item by participant location. There was not a statistically significant difference in overall knowledge between Puerto Rico (M = 5.00, SD = 1.87) and Tampa (M = 5.15, SD = 1.63) participants (t (43) = 0.28, p = 0.78). There was a statistically significant difference for only one knowledge item. Women in Tampa were significantly more likely than women in Puerto Rico to respond correctly to the item: “A woman who does not have an altered breast cancer gene can still get breast or ovarian cancer” (χ2 (1, n = 45) = 4.36, p = 0.04).

Table 3.

Comparison of correct responses by location (n = 45)

| Item | Location | p valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 45) n (%) | Tampa (n = 20) n (%) | Puerto Rico (n = 25) n (%) | ||

| Prevalence | ||||

| One in 10 women will have an altered breast cancer gene. False | 6 (13.33) | 4 (20.00) | 2 (8.00) | 0.38 |

| One half of all breast cancer cases occur in women who have an altered breast cancer gene. False | 8 (17.78) | 2 (10.00) | 6 (24.00) | 0.27 |

| Patterns of inheritance | ||||

| A father can pass down an altered breast cancer gene to his children. True | 28 (62.22) | 12 (60.00) | 16 (64.00) | 0.78 |

| The sister of a woman with an altered breast cancer gene has a 50% risk of having the altered gene. True | 23 (51.11) | 10 (50.00) | 13 (52.00) | 0.89 |

| Cancer risks | ||||

| A woman who does not have an altered breast cancer gene can still get breast or ovarian cancer. True | 31 (68.89) | 17 (85.00) | 14 (56.00) | 0.04* |

| Early-onset breast cancer is more likely due to an altered breast cancer gene than is late-onset breast cancer. True | 28 (62.22) | 11 (55.00) | 17 (68.00) | 0.37 |

| A woman who has an altered breast cancer gene has a higher ovarian cancer risk. True | 29 (64.44) | 11 (55.00) | 18 (72.00) | 0.24 |

| All women who have an altered breast cancer gene get cancer. False | 25 (55.56) | 14 (70.00) | 11 (44.00) | 0.08 |

| Risk management options | ||||

| A woman who has her breasts removed can still get breast cancer. True | 30 (66.67) | 12 (60.00) | 18 (72.00) | 0.40 |

| Ovarian cancer screening tests often do not detect cancer until after it spreads. True | 9 (20.00) | 5 (25.00) | 4 (16.00) | 0.48 |

| Having ovaries removed will definitely prevent ovarian cancer. False | 11 (24.44) | 5 (25.00) | 6 (24.00) | 1.00 |

*p ≤ 0.05

aχ2 tests of homogeneity used to compare groups; Fisher's exact test used for variables with ≤5 in at least one cell

Knowledge about hereditary cancer by demographic and clinical characteristics

Out of the 11 knowledge items, the average number of correct responses for all participants was 5.07 (SD = 1.75). There was a statistically significant difference in composite knowledge by educational status (F (3, 40) = 3.75, p = 0.02). Tukey's HSD follow-up tests demonstrated that those with less than a high school education (M = 3.20, SD = 1.92) were significantly less knowledgeable about HBOC when compared to those who graduated from high school (M = 5.73, SD = 1.19), as well as those with a college degree (M = 5.56, SD = 1.50). A statistically significant difference in knowledge was also observed for personal history of breast cancer (t (43) = 2.01, p = 0.05). A higher knowledge score was observed for women with a personal history of breast cancer before age 50 (M = 5.75, SD = 1.44) than those without a personal history (M = 4.69, SD = 1.81).

Discussion

Despite differences in location, our sample was fairly similar with respect to most sociodemographic and cultural characteristics assessed. Women in Puerto Rico were more likely to report lower income levels than those in Tampa, reflecting differences in median household income between Puerto Rico ($18,401) and Florida ($47,778) (Semega 2009). With respect to cultural factors, women in Tampa indicated a greater preference for English language compared to women from Puerto Rico. While Spanish and English are the official languages of Puerto Rico, Spanish is the dominant language. According to data from the Year 2000 Census, 85% of those living in Puerto Rico reported speaking primarily Spanish at home, and of that group, only 28% felt that they could speak English “very well” (US Census Bureau 2000). Although Puerto Ricans are taught English as a second language from kindergarten through high school, it does not appear to be the preferred primary language for daily communication in Puerto Rico. Furthermore, the language of recruitment materials may need to be either bilingual or English based in Tampa compared to bilingual or Spanish based in Puerto Rico.

Our study found that overall interest in GT for HBOC is high, with 100% of Puerto Rican and 70% of Tampa participants agreeing that they would have a GT in the next 6 months if it were made available to them. The Tampa-based women expressed similar levels of interest to previous studies in the general population and other US-based Hispanic populations. A systematic review that included 25 studies that assessed interest in GT for hereditary cancer found that hypothetical uptake (i.e., testing is not offered in the context of the study) was 66% (Ropka et al. 2006). Previous studies that looked at interest in GT among Hispanic women had even higher rates of interest between 82% and 85% (Ramirez et al. 2006; Ricker et al. 2007). Early data suggest this interest may extend to actual uptake of cancer genetics services. In a recent study of attendance for cancer genetic counseling appointments among a predominantly Hispanic population, 80% of women kept their appointments (Ricker et al. 2006).

With respect to facilitators for GT, the majority of women in Puerto Rico and Tampa agreed that having a provider-recommend GT was important. This finding is similar to previous studies in the USA that indicate physician recommendation represents a powerful motivation for uptake of cancer genetics services (Ricker et al. 2006; Ropka et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2005). Therefore, physicians can play an important role in identifying and informing at-risk women about HBOC and GT. The other motivation for testing that a large proportion of women from both locations agreed upon was if the information could help children make health care decisions. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have found that providing information to family members, particularly children, is one of the most important predictors of interest in and/or intention to obtain GT for a variety of hereditary cancers (Kinney et al. 2000, 2001; Lerman et al. 1995; Ulrich et al. 1998). Given the importance placed on the family in Hispanic culture, health care decisions have been found to be made more collectively, which supports these findings (Flores 2000; Granda-Cameron 1999; Pasick et al. 2009).

Despite the high interest in GT, there were some factors cited by both women in Puerto Rico and Tampa that may serve as barriers to uptake. Although barriers were cited far less frequently than motivators, 20–40% of women in each group cited both cost and possible pain associated with the test as two main barriers. It is not surprising that cost was the main barrier cited by women in each group. In the USA, Hispanics are more likely to be either under- or uninsured. The cost of comprehensive BRCA testing is between $3,000 and $4,000 (Daly 2004). In the USA, many insurance plans do cover the majority of costs associated with GT for HBOC for individuals meeting certain criteria (Kieran et al. 2007); however, Hispanics in the USA are approximately three times more likely than Whites to be uninsured (Anton-Culver et al. 2000). Currently, in the USA, the Medicare program (national insurance for individuals ≥age 65) covers the cost of GT if certain clinical criteria are met (http://www.cms.gov/mcd). Additionally, at the time this study was conducted, the current national health care system in Puerto Rico did not cover the cost of GT. However, more recent information indicates that the three major health insurance companies in Puerto Rico (Triple-S, Humana, and MCS) are now covering the cost of the test with deductibles ranging from 0% to 30%. While women may not know the exact cost of GT, concerns about out-of-pocket health care expenses may deter many women from enquiring about or accessing genetic services.

The next most frequently cited barrier by women in each group was concerns about whether the test would be painful. This may reflect women's minimal knowledge about GT. Data from both the 2000 and 2005 National Health Interview Survey suggested that less than one third of Puerto Rican women have heard of GT for inherited cancer susceptibility, compared to approximately half of all Whites (Heck et al. 2008; Vadaparampil et al. 2006; Wideroff et al. 2003). A recent analysis of qualitative data from the larger study based in Tampa further supports this lack of familiarity with cancer-related GT as participants from various Hispanic ethnicities, including Puerto Rico, would not know how to describe GT to a friend (Vadaparampil et al. 2010a). Thus, given low baseline levels of familiarity with the availability of GT for hereditary cancer, it is possible that the way the item was phrased (“I would not have GT if the test was too painful”) may have led women to believe that there were other procedures beyond a blood draw for GT. Perhaps women assumed cancer GT to be similar to GT in the context of the prenatal care where procedures beyond a blood draw, such as amniocentesis, may be performed as part of GT.

Further evidence of this lack of knowledge is found in the current study results, which suggests that, on average, women from both Puerto Rico and Tampa correctly answered fewer than 50% of questions about HBOC. Of the areas of knowledge that were assessed, the area with the greatest deficit appeared to be related to prevalence of BRCA mutations and BRCA-associated breast cancer risk. Our items were not designed to evaluate whether women were incorrectly answering based on the beliefs that the prevalence was higher or lower for these two questions. However, a recent study which compared perceived cancer risk across various racial/ethnic groups among respondents of the Year 2007 Health Information Trends Survey found that Hispanics had lower levels of perceived risk compared to Whites after adjusting for key sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender). Additional analyses revealed that perceived cancer risk varied less strongly with regard to family history among Hispanics compared to Whites and Blacks Orom et al. (2010). While overall knowledge for both groups was low, women in Tampa were more likely to know that a woman could still develop cancer in the absence of an altered breast cancer gene. This may suggest that the women in Puerto Rico placed a greater emphasis on the role of genetics in breast cancer risk. Therefore, women in Puerto Rico may need to receive educational messages about other breast cancer risk factors (e.g., lifestyle, age) to put the role of genetic factors into context.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to look at a cross-national sample of Puerto Rican women to evaluate interest and knowledge related to HBOC and GT. Despite the availability of GT for hereditary cancer for over a decade in the USA, extensive media coverage, and direct-to-consumer advertisements related to GT, there were minimal differences with respect to knowledge and interest in GT for HBOC between Puerto Ricans living in Puerto Rico and Tampa.

Limitations

While this study was an important first step in exploring interest and attitudes related to HBOC and GT among Puerto Rican women, there are some limitations that should be considered. First, there were some differences in demographic characteristics that may have impacted comparison between the Tampa and Puerto Rico sample. Although not statistically significant, the Puerto Rico sample was older. The Puerto Rico sample was also significantly less likely to indicate English language preference. However, due to the small sample of study participants (n = 45), we were unable to explore the impact of these differences on our outcomes of interest. Second, a convenience sample was utilized in the study, limiting generalizability of study findings. Furthermore, women who self-select to participate in studies, such as this one, may be systematically different from those who do not choose to participate. Thirdly, there were slightly different recruitment approaches used in Puerto Rico and Tampa which may impact the comparability of participants. However, we adapted our recruitment approach in Puerto Rico based on the advice of individuals who lived and worked with our target population in Puerto Rico. It is possible that these women may inherently be more interested in matters related to health and cancer prevention and treatment. Consequently, they may express more interest in GT, as described in this study. Finally, we used single items to explore barriers and facilitators to GT, thus precluding in-depth understanding of why women may have cited these factors as relevant to their interest in GT. Further, more in-depth investigation of the factors associated with GT among larger samples of Puerto Rican women living in Puerto Rico and Tampa is warranted.

Conclusions

BRCA genetic counseling and GT remain largely underutilized among Hispanic populations in the USA and is not readily available in Puerto Rico. Thus, for Puerto Rican women in both locations, participation in research studies may be an important means of accessing BRCA genetic counseling and GT. Research study recruitment efforts should take into account the differences in sociodemographic characteristics by participant location; specifically, recruitment materials should be tailored based on language preferences, and recruitment endeavors should address participant financial challenges associated with follow-up care. The data from this study suggest that women in Puerto Rico and Tampa are interested in obtaining GT. However, when questioned further, women from both locations cited cost as a main barrier to uptake of GT. Therefore, research studies may enhance participation rates by highlighting that GT may be available at minimal or no cost to study participants.

Conversely, there were key areas that may motivate women to have GT. Given the importance placed on provider recommendation as a motivation for GT, health care providers may be an important group to reach women who are candidates for BRCA GT. Similarly, emphasizing the benefits of participating in genetic counseling and testing for family members, particularly siblings and adult children, may also serve as a factor to enhance participation in future studies. Finally, given that protocols offering BRCA GT generally include genetic counseling, this study provides key knowledge deficits that should be addressed, particularly with regard to prevalence of BRCA mutations and BRCA-associated cancer risks. Women in Puerto Rico may need additional information about the role (and interplay) of genetics with other breast cancer risk factors. Based on our preliminary results, there are key attitudinal and knowledge factors that warrant further consideration in the context of recruitment strategies and protocol development for research studies to establish the prevalence and penetrance of BRCA mutations in the Puerto Rican population.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by Grant 1 R03 HG003887 from the National Human Genome Research Institute and by NIH U56 10-14352-03-07. The work contained within this publication was supported in part by the Survey Methods Core Facility at Moffitt Cancer Center. We would also like to thank Ms. Carmen Pacheco and Mr. Juan Carlos Vega for their assistance with recruitment in Puerto Rico.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Anton-Culver H, Cohen P, Gildea M, Ziogas A. Characteristics of BRCA1 mutations in a population-based case series of breast and ovarian cancer. European J Cancer. 2000;36(10):1200–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrigan D, Dodd K, Troiano RP, Reeve BB, Ballard-Barbash R (2006) Physical activity and acculturation among adult Hispanics in the United States. Res Q Exerc Sport 77(2):147–157 [DOI] [PubMed]

- US Census Bureau (2000) US census 2000 demographic profiles: Puerto Rico. US Census Bureau

- Chen S, Iversen ES, Friebel T, Finkelstein D, Weber BL, Eisen A, et al. Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large United States sample. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):863–871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly MB. Tailoring breast cancer treatment to genetic status: the challenges ahead. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1776–1777. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G. Culture and the patient-physician relationship: achieving cultural competency in health care. J Pediatr. 2000;136(1):14–23. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(00)90043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D, Easton DF, Bishop DT, Narod SA, Goldgar DE. Risks of cancer in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Lancet. 1994;343(8899):692–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez Burchard E, Borrell LN, Choudhry S, Naqvi M, Tsai HJ, Rodriguez-Santana JR, et al. Latino populations: a unique opportunity for the study of race, genetics, and social environment in epidemiological research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2161–2168. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granda-Cameron C. The experience of having cancer in Latin America. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L, Akumatey B, Adeokun L. Fear, hope and social desirability bias among women at high risk for HIV in West Africa. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2005;31(4):285–287. doi: 10.1783/jfp.31.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck JE, Franco R, Jurkowski JM, Sheinfeld Gorin S. Awareness of genetic testing for cancer among United States Hispanics: the role of acculturation. Commun Genet. 2008;11(1):36–42. doi: 10.1159/000111638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood P, Shenton A, Lalloo F, Evans DG, Howell A (2001) Risk perception and cancer worry: an exploratory study of the impact of genetic risk counselling in women with a family history of breast cancer. J Med Genet 38(2):139–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute (2003) SAS Institute (version 9.1). SAS Institute, Cary

- Jacobellis J, Martin L, Engel J, VanEenwyk J, Bradley L, Kassim S, et al. Genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: evaluating direct-to-consumer marketing–Atlanta, Denver, Raleigh-Durham, and Seattle, 2003. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(27):603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John EM, Miron A, Gong G, Phipps AI, Felberg A, Li FP, et al. Prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1 mutation carriers in 5 US racial/ethnic groups. J Am Med Association. 2007;298(24):2869–2876. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.24.2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieran S, Loescher LJ, Lim KH. The role of financial factors in acceptance of clinical BRCA genetic testing. Genet Test. 2007;11(1):101–110. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Choi YA, DeVellis B, Millikan R, Kobetz E, Sandler RS. Attitudes toward genetic testing in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Pract. 2000;8(4):178–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.84008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Croyle RT, Dudley WN, Bailey CA, Pelias MK, Neuhausen SL. Knowledge, attitudes, and interest in breast-ovarian cancer gene testing: a survey of a large African-American kindred with a BRCA1 mutation. Prev Med. 2001;33(6):543–551. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Seay J, Balshem A, Audrain J. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of breast cancer patients. Am J Med Genet. 1995;57(3):385–392. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320570304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Bonney G et al (1996) BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. A prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. JAMA 275(24):1885–1892 [PubMed]

- Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, Kerner J, Gomez-Caminero A, Hughes C et al (1997a) Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. J Natl Cancer Inst 89(2):148–157 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lerman C, Schwartz MD, Lin TH, Hughes C, Narod S, Lynch HT (1997b) The influence of psychological distress on use of genetic testing for cancer risk. J Consult Clin Psych 65(3):414–420 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe K, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P, Tung N, Olivotto I, Warner E, et al. Contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(12):2328–2335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchawar J, Hensley-Alford S, Laurion S, Ellis J, Kulchak-Rahm A, Finucane ML, et al. Impact of direct-to-consumer advertising for hereditary breast cancer testing on genetic services at a managed care organization: a naturally-occurring experiment. Genet Med. 2005;7(3):191–197. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000156526.16967.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchawar J, Laurion S, Ritzwoller DP, Ellis J, Kulchak-Rahm A, Hensley-Alford S. Assessing controversial direct-to-consumer advertising for hereditary breast cancer testing: reactions from women and their physicians in a managed care organization. Am J Managed Care. 2005;11(10):601–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullineaux LG, Castellano TM, Shaw J, Axell L, Wood ME, Diab S, et al. Identification of germline 185delAG BRCA1 mutations in non-Jewish Americans of Spanish ancestry from the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Cancer. 2003;98(3):597–602. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orom H, Kiviniemi MT, Underwood W, 3rd, Ross L, Shavers VL. Perceived cancer risk: why is it lower among nonwhites than whites? Canc Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(3):746–754. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasick RJ, Barker JC, Otero-Sabogal R, Burke NJ, Joseph G, Guerra C. Intention, subjective norms, and cancer screening in the context of relational culture. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(5 Suppl):91S–110S. doi: 10.1177/1090198109338919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JA, Vadaparampil ST, Kramer J, Moser RP, Court LJ, Loud J et al (2006) Familial testicular cancer: interest in genetic testing among high-risk family members. Genet Med 8(12):760–770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Powe BD (1996) Cancer fatalism among African-Americans: a review of the literature. Nurs Outlook 44(1):18–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Powe BD, Weinrich S (1999) An intervention to decrease cancer fatalism among rural elders. Oncol Nurs Forum 26(3):583–588 [PubMed]

- Quinn GP, McIntyre J, Vadaparampil ST (2011) Preferences for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer information among Mexican, Cuban and Puerto Rican women at risk. Public Health Genomics 14(4-5):248–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ramirez AG, Talavera GA, Marti J, Penedo FJ, Medrano MA, Giachello AL, et al. Redes En Accion. Increasing Hispanic participation in cancer research, training, and awareness. Cancer. 2006;107(8 Suppl):2023–2033. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker C, Lagos V, Feldman N, Hiyama S, Fuentes S, Kumar V, et al. If we build it…will they come?–establishing a cancer genetics services clinic for an underserved predominantly Latina cohort. J Genet Couns. 2006;15(6):505–514. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricker CN, Hiyama S, Fuentes S, Feldman N, Kumar V, Uman GC, et al. Beliefs and interest in cancer risk in an underserved Latino cohort. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson M, Svahn T, McCormick B, Borgen P, Hudis CA, Norton L, et al. Appropriateness of breast-conserving treatment of breast carcinoma in women with germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2: a clinic-based series. Cancer. 2005;103(1):44–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropka ME, Wenzel J, Phillips EK, Siadaty M, Philbrick JT. Uptake rates for breast cancer genetic testing: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(5):840–855. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari K, Choudhry S, Tang H, Naqvi M, Lind D, Avila PC, et al. Genetic admixture and asthma-related phenotypes in Mexican American and Puerto Rican asthmatics. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;29(1):76–86. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Brogan B, Peshkin BN, Isaacs C, DeMarco T, et al. Utilization of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(4):1003–1007. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semega J (2009) Median household income for states: 2007 and 2008 american community surveys. US Census Bureau

- Steidel AG, Contreras JM (2003) A new familism scale for Latina populations. Hispanic J Behav Sci 25(3):312–330

- Ulrich CM, Kristal AR, White E, Hunt JR, Durfy SJ, Potter JD. Genetic testing for cancer risk: a population survey on attitudes and intention. Commun Genet. 1998;1(4):213–222. doi: 10.1159/000016166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, Trapido E. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):618–623. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil ST, Azzarello L, Pickard J, Jacobsen PB (2007) Intention to obtain genetic testing for melanoma among first degree relatives of melanoma patients. Am J Health Educ 38(3):148–155

- Vadaparampil S, McIntyre J, Quinn GP. Awareness, perceptions, and provider recommendation related to genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer risk among at-risk Hispanic women: similarities and variations by sub-ethnicity. J Genet Couns. 2010;19(6):618–629. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9316-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil ST, Quinn GP, Small BJ, McIntyre J, Loi CA, Closser Z, et al. A pilot study of hereditary breast and ovarian knowledge among a multiethnic group of Hispanic women with a personal or family history of cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14(1):99–106. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, Nelson R, Ricker C, Herzog J, et al. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1666–1671. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzel JN, Lagos VI, Herzog JS, Judkins T, Hendrickson B, Ho JS, et al. Evidence for common ancestral origin of a recurring BRCA1 genomic rearrangement identified in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1615–1620. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, Croyle RT, Freedman AN. Awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Commun Genet. 2003;6(3):147–156. doi: 10.1159/000078162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378(6559):789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]