Abstract

Background

Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) is a promising treatment for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD). However, previous randomized trials have not systematically examined the combination of CBM for attention (CBM-A) and interpretation (CBM-I), or the credibility and acceptability of these protocols.

Methods

We conducted a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial (N = 32) to examine the efficacy of a CBM treatment called Attention and Interpretation Modification (AIM) for SAD. AIM comprised eight, twice weekly computer sessions with no therapist contact. During AIM, participants (1) completed a dot probe task in which probes always followed neutral faces when paired with a disgust face, thereby directing attention away from threat and (2) completed a word-sentence association task in which they received positive feedback for making benign interpretations of word-sentence pairs and negative feedback for making negative interpretations. We also assessed participants’ perceived credibility of and satisfaction with AIM.

Results

Participants receiving AIM reported significantly reduced self-reported (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale) symptoms of social anxiety relative to the placebo. These gains were also evident on a behavioral measure (performance on an impromptu speech). AIM met our benchmarks for credibility and acceptability in this community sample, although credibility ratings were modest. Participants reported that CBM-I was more helpful than CBM-A.

Conclusions

A combined CBM treatment produced medium to large effects on social anxiety. Participants rated AIM as moderately credibly and acceptable. Should these findings be replicated in larger samples, AIM has the potential to be a widely accessible and efficacious treatment for SAD.

Keywords: social anxiety, cognitive bias modification, treatment, attention bias, interpretation bias

Introduction

Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) interventions directly target cognitive mechanisms associated with vulnerability to anxiety disorders, such as attention and interpretation biases (see (1, 2)). CBM affects cognition via repeated practice on tasks that require rapid processing (for reviews of CBM, see ((3-5)). To date, two independent randomized controlled trials (RCT) have demonstrated preliminary efficacy of CBM targeting attention bias (CBM-A) in individuals with Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) (6, 7). Both trials utilized the same protocol, which comprised a dot probe task completed in eight, twice-weekly computer sessions. Between-group effect sizes (d = 0.35 to 1.59) were comparable to existing psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for SAD, and symptom reduction was maintained at a four month follow-up.

Researchers have also developed CBM tasks to target interpretation bias (CBM-I). Although no RCTs have been conducted in samples meeting diagnostic criteria for SAD, one randomized trial examined a CBM-I treatment in highly socially anxious individuals (8). After eight twice-weekly sessions of a CBM-I intended to reinforce benign interpretations and extinguish threat interpretations of ambiguous sentences, CBM-I successfully decreased social anxiety symptoms compared to the placebo condition.

In order to maximize clinical impact, a logical next step is the combination of CBM-A and CBM-I treatments. Recently, a small (n = 13) open trial (9) tested a combined CBM-A-I treatment and the feasibility of delivering CBM in an outpatient psychology office. In their sample of patients with SAD or Generalized Anxiety Disorder, CBM yielded significant effects on state and trait anxiety. Although these results are encouraging, they must be interpreted in the context of several major design limitations (e.g., lack of control group, small sample, completer analyses).

Positive results are promising given the lack of clinician contact, brevity, and ease of administration of CBM. However, most previous studies did not explicitly assess credibility or patient acceptability and satisfaction. Regarding credibility, researchers have asked participants at the end of the study whether they believed they received a treatment or placebo. Only 6% of participants correctly guessed that they received a treatment following CBM-A (7), compared to 46% following CBM-I (8). While such findings quell any concerns about demand effects, they suggest that CBM may not be a very credible treatment, particularly CBM-A.

Regarding acceptability, a recent open trial of CBM-A suggests that this type of treatment is acceptable to anxious children and their parents based on a participant acceptability questionnaire(10). However, acceptability has yet to be systematically examined in adults with SAD, which is crucial for eventual update of treatments in the real world. Brosan and colleagues’ open trial of a combined CBM-A-I protocol informally asked patients about their experiences. Patients found CBM-I to be helpful in increasing their awareness of their negative thinking patterns. However, patient comments suggest that CBM-A may have limited acceptability due to its “boring” nature (p.5).

Attrition rates from previous CBM studies (0% to 8%) do not provide ideal data regarding acceptability because each study was conducted in an anxiety clinic and provided compensation for session attendance. We do not know the tolerability of these procedures when participants are recruited directly from the community and are not paid for completing sessions. These data, as well as the previously mentioned potential problems with credibility, suggest that a more systematic evaluation of credibility and patient acceptability is warranted.

Thus, the current RCT tested an Attention and Interpretation Modification (AIM) CBM treatment for SAD and examined its efficacy, credibility, and acceptability. We aimed to examine the potential for AIM to have real world utility. First, we combined the CBM-A and CBM-I treatments in order to maximize clinical impact. We also provided participants with a brief treatment rationale stating that the computer programs were designed to help participants develop healthier mental habits. Second, we recruited patients from the general community and primary care clinics, and we allowed patients to be engaged in concurrent treatment in order to obtain a less selected sample. Third, we did not compensate participants for session attendance in order to obtain more informative attrition rates. Finally, we included established measures of credibility and acceptability. We expected participants to report less social anxiety symptoms following AIM compared to a control condition. To extend previous RCT's assessment of efficacy, we also included a behavioral measure of social anxiety (i.e., impromptu speech). Based on our experience and preliminary findings from Brosan and colleagues (9), we expected participants receiving AIM to rate the CBM-A task as less acceptable compared to the CBM-I task.

Method

Design

The study was a 2 (Condition: AIM, Placebo Condition (PC)) × 5 (Time: pre-treatment, week 1, week 2, week 3, post-treatment) design. Participants were randomly assigned to AIM (n = 20) or PC (n = 12) by a colleague not otherwise connected with the study using a random number generator.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited through brochures in primary care clinics (n=5), mental health provider referral (n=2), internet (n=13), flyers in the community (n=10), and word of mouth (n=2). Participants varied in age (18 to 79), and both groups had 25% minority representation. English was a second language for three participants. Most participants were receiving some form of concurrent treatment. Please see Table 1 for demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| AIM (n = 20) | PC (n = 12) | |

| Female | 16 (80%) | 8 (67%) |

| Age (M, SD) | 37 (18.4) | 38 (11.4) |

| Ethnicity/Race | ||

| Caucasian | 15 (75%) | 9 (75%) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 1 (5%) | 3 (25%) |

| African American | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Highest Education Level | ||

| High School or GED | 13 (65%) | 3 (25%) |

| College Degree | 7 (35%) | 9 (75%) |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 4 (20%) | 3 (25%) |

| Employed | 7 (35%) | 8 (67%) |

| Student | 5 (25%) | 1 (8%) |

| Retired | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Current Treatment | ||

| Pharmacotherapy only | 3 (15%) | 3 (25%) |

| Non-CBT Psychotherapy only | 1 (5%) | 3 (25%) |

| Combined Treatment | 3 (15%) | 4 (33%) |

Note. Ethnicity percentages total over 100% due to one participant who reported both African American and Latina race/ethnicity. College Degree comprises Associates or Bachelor-level degrees. Of note, many of the AIM participants were in college during the study and anticipating college degrees.

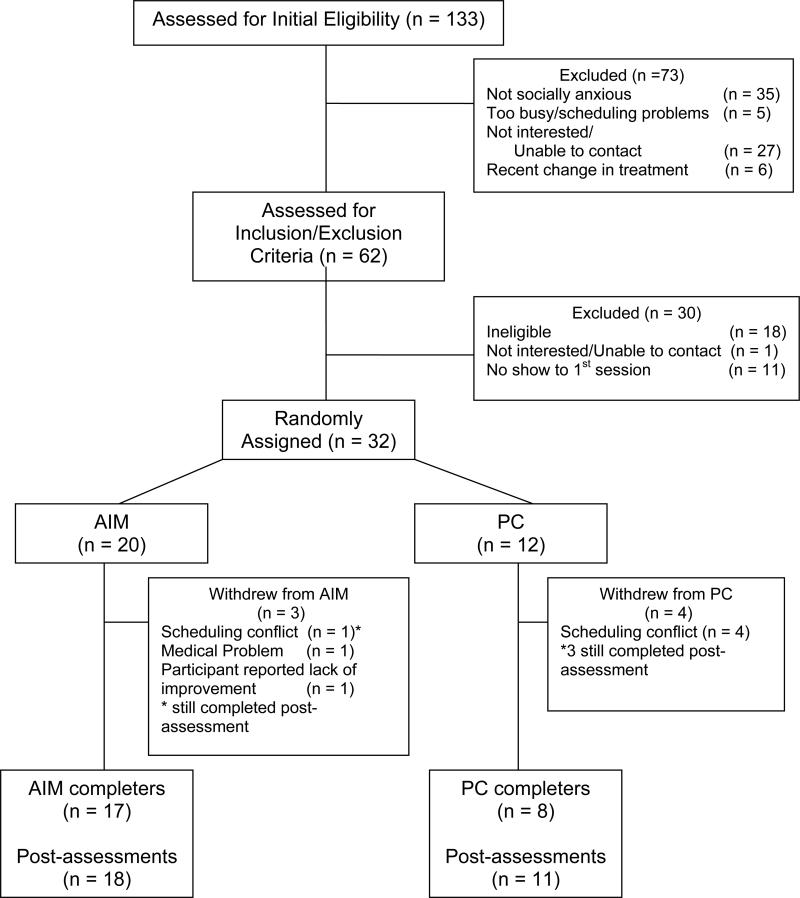

Participant Flow

Potential participants were initially screened for eligibility using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-self-report (LSAS-SR(11)). Participants scoring 30 or above (12) were invited to participate in the pre-treatment assessment. A score of 30 or above has been identified as an optimal cut-off for identifying cases of SAD (12, 13) and was chosen to minimize false positives in the screening process. Inclusion criteria included a DSM-IV diagnosis of SAD established by a licensed clinical psychologist using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (14). Exclusionary criteria included current (a) suicidal intent, (b) substance dependence, (c) psychosis or manic episode, (d) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and (e) change in pharmacological treatments during the 12 weeks prior to study entry. Eleven eligible participants did not attend their first session and were replaced by a participant assigned to that same group. Participants were enrolled between September of 2009 and October of 2010. Figure 1 summarizes participants’ progress through the study.

Figure 1.

Participant Flowchart

Measures and CBM tasks1

Efficacy

Our primary outcome measure was the LSAS-SR (11). The LSAS is a 24-item scale that provides separate scores for fear and avoidance of social interaction and performance situations over the past week. The LSAS has good psychometric properties (15) and is a widely used measure in SAD treatment outcome research (e.g., (16). The self-report version correlates strongly with the interview version and also has excellent psychometric properties (17). Participants completed the LSAS-SR at pre-treatment, week 1, week 2, week 3, and post-treatment.

We also administered a behavioral assessment of social anxiety. Participants were asked to complete a five-minute impromptu speech, following the same procedure as in previous studies (18, 19). Participants were presented with a list of five topics: three topics were from previous studies (abortion, nuclear power, the American Health System; Hofmann, Newman, Ehlers, & Roth, 1995) and two less controversial topics (hobbies, someone you admire) were selected based on our pilot work. Participants were required to choose a different topic during the post-assessment.

Two research assistants blind to participant condition were trained to rate speech quality using the Performance Rating Form (PRF; (20)), which assesses 12 specific aspects of performance (e.g., eye contact with audience, clear voice) and 5 global aspects of performance (e.g., kept audience interest, generally spoke well). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Scores are calculated by reversing appropriate items and summing the items, such that higher scores signify better performance. This scale has been shown to have good internal consistency (r = .84; (20)). Raters were trained for reliability by rating speeches from participants not included in the current study and meeting a gold standard rating goal for three reliability tapes. Each speech was rated by one of the raters, and 15 speeches were rated by both raters to obtain a reliability estimate (r = .85).

Credibility

We assessed perceived credibility of AIM with the Credibility/ Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ; (21, 22)). We examined the mean credibility rating (3 items rated from 1 to 9, e.g., “at this point, how logical does the treatment seem?”), as well as expectancy, i.e., the mean percentage of improvement participants expected (2 items rated from 0 to 100%). The CEQ has demonstrated good internal consistency (α ranges from = .79 to .90) and is predictive of some outcomes in clinical trials(22). We administered the CEQ immediately following the first AIM/PC session. Thus, participants rated credibility and expectancy after receiving a brief rationale and completing the computerized tasks one time. Finally, we also asked participants what condition they believed they received during their post-treatment assessment.

Acceptability and Satisfaction

To assess acceptability and satisfaction, we first examined attrition rates and number of sessions attended. Second, we examined a client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ; (24)), an 8-item, commonly used measure of treatment satisfaction. The CSQ total score ranges from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction, and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (25). Third, we examined a post-treatment Exit Questionnaire developed specifically for this study that assessed perceived helpfulness of each study component using a Likert-scale (0 = not at all to 7 = very much). Participants were asked separately about the helpfulness of the attention and interpretation tasks and their preferred number of sessions and treatment setting (i.e., provider's office versus home).

Benchmarks

We chose benchmarks for our credibility and acceptability measures based on face validity and clinical experience, and in the context of the unique aspects of CBM (no clinician contact, limited rationale, low face validity). Previous studies of psychosocial treatment for anxiety disorders have reported mean credibility ratings of seven and expectancy ratings of around 70% (21, 23). We chose modest benchmarks of five or above for credibility and 50% or above for expectancy. Our benchmark for satisfaction was a mean score of 3 (e.g., “mostly satisfied”) on each item on the CSQ, resulting in a total score of 24.

AIM Program

During the first session, participants received a packet providing brief psychoeducation about anxiety and cognitive biases (referred to as mental habits), as well as a treatment rationale (see Appendix). In brief, participants were told that the program would help them to develop better mental habits related to anxiety and that repeated practice was necessary to develop the new habits. Participants completed the CBM-A task followed by the CBM-I task during each session.

The CBM-A task was based on previous (6) dot probe tasks designed to bias attention away from threat stimuli. During each session, participants saw 160 trials that comprised combinations of probe type (E or F), probe position (top or bottom), disgust facial expression position (top or bottom), and person (four male and four female faces). Each trial began with a fixation cross (“+”) presented in the center of the monitor for 500 ms. Immediately following termination of the fixation cue, the computer presented two faces of the same individual for 500 ms, one face on top and one on bottom. One face displayed a neutral expression and one disgust. Immediately following termination of the faces, a probe (either the letter E or F) appeared in the previous location of one of the two faces. Participants were instructed to decide whether the letter was an E or an F and press the corresponding button (left or right) on the computer mouse. The probe remained on the screen until participants responded, after which the next trial began. Participants were told to perform the task as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. In order to train attention away from threat, the probes always replaced the neutral faces.

The CBM-I task was a version of a previously used word-sentence association paradigm (8). The task was designed to extinguish threat interpretations and encourage benign interpretations of ambiguous situations. A trial began with a fixation cross that appeared on the computer screen for 500 ms. Second, a word representing either the negative (“embarrassing”) or benign (“funny”) interpretation of a sentence (“people laugh after something you said”) that followed appeared in the center of the computer screen for 500 ms. Third, the ambiguous sentence appeared. Participants were instructed to press ‘#1’ on the number pad if the word and sentence were related or to press ‘#3’ on the number pad if the word and sentence were not related. Finally, participants received feedback about their responses. Participants received positive feedback (“You are correct!”) when they endorsed the benign interpretation or rejected the negative interpretation of the ambiguous sentence. Participants received negative feedback (“Incorrect”) when they endorsed the negative interpretation or rejected the benign interpretation. Participants completed 150 trials in random order during each session.

Placebo Control (PC)

Participants in the PC received the same psychoeducation and rationale and completed similar computer tasks as AIM participants. The computer tasks differed in two ways. First, in the probe task, the probe replaced neutral and disgust faces with equal frequencies. Second, in the word-sentence relatedness task, the computer presented words that were related or unrelated to some superficial aspect of the ambiguous sentences (e.g., “sand” - “you play at the beach”). Thus, words were not related to the social interpretation of the sentence, but they were related or unrelated to the sentence. Similar to AIM, participants received positive or negative feedback about the accuracy of their responses.

Procedure

The Brown University Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. Participants were informed that, depending on their random group assignment, they would complete either a placebo condition that was not designed to influence their anxiety or an experimental treatment that was designed to reduce their anxiety. Participants and research assistants were blind to participant condition. To ensure that participants remained unaware of their condition, each participant received an envelope that contained a condition number that they entered into the computer to start the assigned computer program. Participants completed eight, 30-minute sessions twice per week for four weeks. All participants were offered community referrals following their post-treatment assessment. Additionally, at post-treatment, participants assigned to the PC were offered AIM. Participants received $20 for each assessment, but they were not compensated for AIM/PC session attendance.

Results

At pre-treatment, groups did not differ on any of the demographic variables or LSAS (ps > .1). All analyses presented are intent-to-treat.

Efficacy

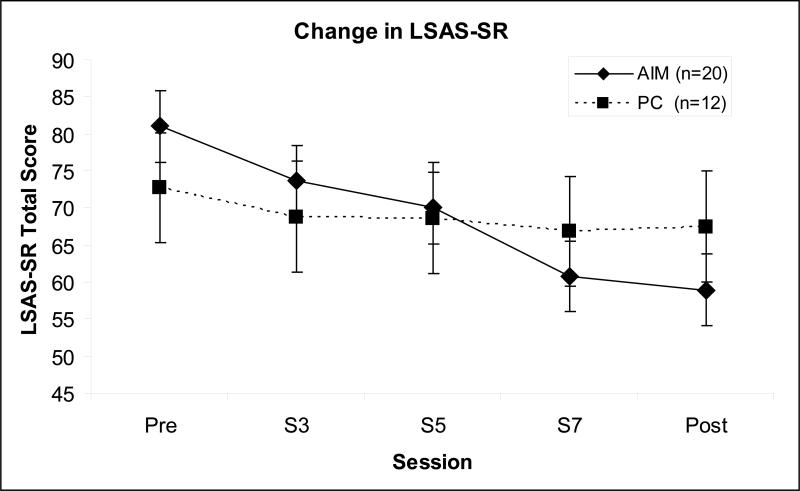

We submitted LSAS scores to a 2 (Group: AIM, PC) × 5 (Time, Pre, week 1, 2, 3, Post) repeated measures ANOVA. Given the small sample, we utilized last observation carried forward to handle missing data. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of Time, F(4, 120) = 9.37, p < .001, that was qualified by a significant interaction of Time by Group, F(4, 120) = 3.79, p = .006. As can be seen in Figure 2, the AIM group reported lower LSAS scores over time than the PC group. The between group, pre-post effect size was medium to large in size (Cohen's d = .70).

Figure 2.

Change in LSAS-SR

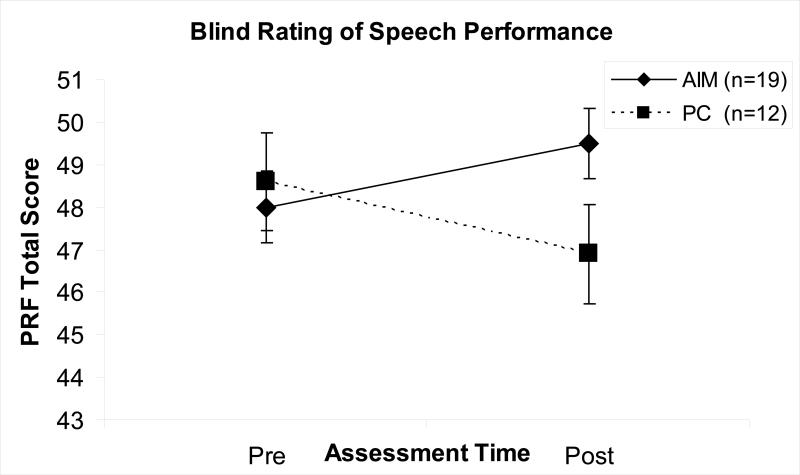

For the impromptu speech (see Figure 3), we submitted the blind raters’ PRF scores to 2 (Group: AIM, PC) × 2 (Time: Pre, Post) ANOVA. This analysis revealed a significant interaction of Time by Group, F(1, 29) = 10.24, p =.003, with the AIM group having better speech quality than the PC group at post-assessment. The between group, pre-post effect size was large (Cohen's d = .85).

Figure 3.

Change in Speech Performance

Credibility

At baseline, the AIM group (n = 11; smaller n due to the CEQ being added after the study initiated) rated the treatment as moderately credible (M = 6.0, SD = 1.34), which met our a priori benchmark of five. AIM participants’ expectancy for improvement was also in the moderate range (M = 46%, SD = 21.7), which approached our benchmark of 50%. Credibility ratings at baseline were significantly correlated with pre-post change in LSAS (r = .73, p = .01). Expectancy ratings showed moderate correlations with change in LSAS (r = .53, p < .09). Finally, at post-treatment, approximately 75% of participants in the AIM group believed they had received a treatment, compared to 36% in the PC group.

Acceptability and Satisfaction

Overall, participants found our 8-session, office delivery protocol acceptable. On the post-treatment Exit Questionnaire, most participants reported that eight sessions was appropriate (n= 12, 70.6%); some preferred more sessions (n = 4, 23.5%); and only one participant preferred fewer sessions (6%). The Exit Questionnaire also asked participants about their preferences for treatment setting. Seven participants (41%) would have preferred to complete AIM at home, six (35%) preferred the office delivery, and 2 (12%) had no preference. Of note, many of our participants were either students or unemployed and thus more likely to be able to comply with the office protocol.

Three participants withdrew from AIM (15%), and four withdrew from the PC (33%). Both groups attended a similarly high number of sessions (AIM: M= 7.3. SD = 1.86; PC: M= 6.4, SD =2.61; p = .3). At post-treatment, the AIM group reported high levels of satisfaction on the CSQ (M = 26.2, SD =3.9), which met our benchmark of a total score of 24. On the Exit Questionnaire (items rated from 0 to 7), the AIM group rated the program overall as being moderately helpful with anxiety in social situations (M = 4.1, SD = 1.65). When examining each AIM component separately, participants rated the CBM-A dot probe task as not very helpful (M = 2.7, SD = 2.23), compared to the CBM-I task (M = 5.3, SD = 1.72).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first RCT to examine a combined CBM for attention and interpretation for SAD. AIM demonstrated promising efficacy, with the between-group effect size for change in social anxiety symptoms comparable to previous CBM treatments (6, 7), as well as pharmacological and CBT treatments for social anxiety (16, 26). Moreover, large effects also emerged on our behavioral measure of social anxiety, i.e., blind ratings of impromptu speech quality. This study is now the third to demonstrate efficacy of CBM-A (6, 7) and the second for CBM-I in a clinical SAD sample (9). Moreover, it is the first RCT of CBM to show changes on a behavioral outcome measure.

This study is also the first to systematically examine the credibility and acceptability of CBM as a treatment for adults with SAD. Ratings of credibility and acceptability met our benchmarks. At baseline, participants rated CBM's credibility and their expectancy for improvement in the moderate range. At post-treatment, 75% of AIM participants believed they had received a treatment compared to 36% in the placebo group. These rates for both groups are higher than previous CBM randomized trials. We attribute this to the fact that participants received CBM-I, in addition to CBM-A. CBM-I appears to be more face valid, and indeed, Brosan and colleagues’ (9) open trial of CBM-A-I suggests that patients receiving CBM-I identified a pattern in CBM-I. Additionally, higher rates in the current study may be due to the efforts we made to enhance credibility (i.e., providing psychoeducation and rationale). Finally, credibility and expectancy ratings at baseline correlated with change in social anxiety symptoms. Patient expectations and, in some cases, perceived credibility of a treatment have previously been related to treatment outcome (22), including for SAD (27). Thus, efforts toward enhancing CBM's credibility and expectancy may also enhance its efficacy.

Regarding acceptability of the AIM protocol, participants from both primary clinics and the community were willing to attend sessions without compensation. However, as expected, attrition rates were higher in this community sample (22%) compared to previous CBM trials in which participants were paid for session attendance (0% to 8%). Attrition rates in the current study were more in line with CBT treatments for anxiety (23%) (26). Participants were mostly satisfied with AIM, and total scores on the satisfaction questionnaire met our benchmarks. Results from the exit questionnaire suggest that participants found the CBM-I task more helpful than the CBM-A task.

These findings should be interpreted in the context of the study's limitations. The study was designed as a small, pilot trial. The small sample size had a number of implications. First, random assignment yielded unequal numbers of participants in each group, and thus conclusions regarding group differences are based on a relatively smaller placebo group. Second, the effect sizes should be interpreted with caution given that effect sizes from small samples are known to be unreliable (28). Larger studies are needed to confirm AIM's efficacy. Third, the current study was unable to test proposed mediators due to our small number of participants with complete attention and interpretation bias assessment data. Previous trials using almost identical protocols have demonstrated that changes in attention and interpretation biases were the mechanisms of change. Although there is no reason to believe that results would be different in the current study, we cannot confirm this was the case. Finally, although the inclusion of both CBM-A and CBM-I allowed us to assess acceptability of two components of treatment within one study, it also prevented us from assessing acceptability for each component in isolation. For example, given the low perceived helpfulness ratings of CBM-A, it is possible that attrition rates would be higher for a study examining CBM-A in isolation in a community sample.

Despite these limitations, the current results suggest a number of potential changes that may enhance CBM protocols. First, the combined protocol demonstrated efficacy on self-report and behavioral measures, suggesting that future CBM treatment packages may benefit from targeting multiple biases (although future studies directly testing the superiority of combined treatment are still needed). Second, participants were satisfied with eight sessions, and some even preferred 12 sessions. Given that participants in AIM demonstrated a gradual decrease in social anxiety over the 8 sessions, it is possible that more sessions would result in continued improvement. Thus, protocols may be enhanced by having an option for more sessions or booster sessions. Participants’ preference for delivery setting was split between a provider's office and home. Since it is feasible to deliver CBM-A at home (29), an ideal protocol may be to provide patients with both options when delivering CBM. Finally, efforts toward enhancing the perceived usefulness of CBM-A are warranted. This may be accomplished by enhancing the treatment rationale provided and/or by creating a more engaging task (e.g., increase variety of stimuli, establish reaction time goals).

Conclusions

AIM, a combined CBM-A/CBM-I treatment, was efficacious compared to a placebo control as measured by self-report and behavioral measures. Individuals with SAD found the AIM protocol acceptable and reported high satisfaction. Credibility ratings were modest. Further enhancing CBM's credibility and acceptability is an important pursuit given CBM's potential accessibility and unique features (e.g., standardized computerized delivery, no therapist contact, low demands on patients, brevity). These results add to the growing literature supporting CBM as a treatment for SAD. Thus, CBM may be an important part of our portfolio (see (31)) of treatments as it may be useful for patients who do not respond to or cannot access current treatments and for patients or providers who find existing treatments unacceptable.

Table 2.

Acceptability and Satisfaction of AIM (n=17)

| M (SD) | |

|---|---|

| CSQ: Satisfaction | 26.2 (3.96) |

| Exit Questionnaire (0 = not at all to 7 = very much) | |

| Helpfulness for anxiety in social situations | 4.1 (1.65) |

| Usefulness of CBM-A task | 2.7 (2.23) |

| Usefulness of CBM-I task | 5.3 (1.72) |

Note. AIM = Attention and Interpretation Modification; CSQ = Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. Three participants did not complete post-treatment questionnaires.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an NIMH NRSA post-doctoral fellowship (F32 MH083330) awarded to Dr. Beard. An ADAA Career Development Award awarded to Dr. Beard provided travel funds to present these findings at the 2011 ADAA conference. We thank Hannah Boettcher, Ashley Perry, Mary Howell, and Michelle Cawley for their assistance in data collection and entry.

Financial disclosure statement (past 36 months): Dr. Beard received a Career Development Travel Award to present these findings at the 2011 Anxiety Disorders Association of America (ADAA) annual meeting. Dr. Weisberg has received grant funding from NIMH and Pfizer, was a consultant to SciMed, received funding for manuscript preparation from CME Institute, and funding for educational development from Princeton Healthcare Communications. Dr. Amir has received grant funding from NIMH, has applied for a patent related to the current type of treatment, and is part owner of a company that markets treatments similar to the current paper (conflict of interest is covered by SDSU).

Appendix

Treatment Rationale

How does AIM reduce anxiety?

AIM is different from most treatments. It's not medication or talk therapy. AIM changes how you think and mentally respond to everyday things in your life- your mental habits. AIM changes mental habits in a new way that may be better than past treatments. These mental habits are often hard to control. For example, people with anxiety have a tendency to focus their attention on negative information. They also tend to interpret ambiguous information as negative. This habit is so automatic that it is very difficult to “catch” or change on purpose.

However, just like other habits like typing or riding a bicycle, with practice we can change these mental habits and have new “non-anxiety related” habits become automatic.

Attention bias

People differ in how they focus their attention. What you pay attention to plays an important role in how safe or unsafe you feel. If you tend to focus your attention on negative aspects of a situation or cues that might signal danger, you will be more likely to become excessively anxious. Also, the more you look for something, the more likely it is that you will find it; so if you are always looking for signs of danger, you will be more likely to see danger.

Interpretation bias

People differ in how they interpret ambiguous information in their environment as well. An interpretation bias, or a tendency to interpret situations negatively, also plays an important role in how safe or unsafe each situation seems to you. If you tend to think of situations as negative, you will be more likely to become excessively anxious. Because in everyday life many situations are ambiguous, a negative interpretation bias will lead to most situations being seen as negative. Moreover, by expecting a negative outcome people with anxiety often create what is called a “self-fulfilling prophecy.” For example, if you walk into a party and expect people will not talk to you, you may be cold to them, and as a result, it is more likely that they will not talk to you.

Why Practice?

The AIM programs are very simple and seem like a repetitive computer game. AIM is similar to those “brain games” that improve memory or attention. Most people think it is weird at first, and you will not understand the purpose of the tasks. That's normal! Gaining control over automatic mental habits is like strengthening a muscle in your body, it takes regular training. As you repeat this training each day, it will become easier to do, and you will be faster and more accurate.

Footnotes

The current study included measures of attention and interpretation. However, we do not present these data because our sample size was significantly reduced for these measures due to participants dropping out and therefore not completing the post-assessment and due to technological difficulties with saving the data for three participants.

References

- 1.Koster EHW, Fox E, MacLeod C. Introduction to the Special Section on Cognitive Bias Modification in Emotional Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psycholgoy. 2009;118(1):1–4. doi: 10.1037/a0014379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beard C. Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) for Anxiety: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2011;11(2):299–311. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Haim Y. Research Review: Attention bias modification (ABM): a novel treatment for anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02251.x. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakamata Y, Lissek S, Bar-Haim Y, Britton JC, Fox NA, Leibenluft E, et al. Attention Bias Modification Treatment:A Meta-Analysis Toward the Establishment of Novel Treatment for Anxiety. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:982–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beard C. Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) for Anxiety: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.194. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amir N, Beard C, C. T, Klumpp H, Elias J, Burns M, et al. Attention Training in Individuals with Generalized Social Phobia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:961–73. doi: 10.1037/a0016685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt NB, Richey JA, Buckner JD, Timpano KR. Attention training for generalized social anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/a0013643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beard C, Amir N. A multi-session interpretation modification program: Changes in interpretation and social anxiety symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(10):1135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosan L, Hoppitt L, Shelfer L, Sillence A, Mackintosh B. Cognitive bias modification for attention and interpretation reduces trait and state anxiety in anxious patients referred to an out-patient service: Results from a pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozenman M, Weersing VR, Amir N. A case series of attention modification in clinically anxious youths. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141–73. doi: 10.1159/000414022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mennin DS, Fresco DM, Heimberg RG. Screening for social anxiety disorder in the clinical setting: Using the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:661–73. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rytwinski NK, Fresco DM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME, Liebowitz MR, Cissell S, et al. Screening for Social Anxiety Disorder with the Self-report Version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:34–8. doi: 10.1002/da.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders - patient edition (SCID-I/PI, version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:199–212. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, Holt CS, Welkowitz LA, et al. Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy vs Phenelzine Therapy for Social Phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:1133–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fresco DM, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formats. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:1025–35. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amir N, Weber G, Beard C, Bomyea J, Taylor CT. The effect of a single-session attention modification program on response to a public-speaking challenge in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(4):860–8. doi: 10.1037/a0013445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beard C, Amir N. Negative interpretation bias mediates the effect of social anxiety on state anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34:292–6. doi: 10.1007/s10608-009-9258-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapee RM, Lim L. Discrepancy between self- and observer ratings of performance in social phobics. Journal of Abnormal Psycholgoy. 1992;101:728–31. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:611–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/ expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borkovec TD, Mathews AM. Treatment of Nonphobic Anxiety Disorders: A Comparison of Nondirective, Cognitive, and Coping Desensitization Therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):877–84. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner B. Assessment of patient satisfaction: Development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1983;6:299–314. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(83)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann SG, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult Anxiety Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:621–32. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambless DL, Tran GQ, Glass CR. Predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:221–40. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer HC, et al. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.See J, MacLeod C, Bridle R. The reduction of anxiety vulnerability through the modification of attentional bias: A real-world study using a home-based cognitive bias modification procedure. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(1):65–75. doi: 10.1037/a0014377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dandeneau SD, Baldwin MW, Baccus JR, Sakellaropoulo M, Pruessner JC. Cutting stress off at the pass: Reducing vigilance and responsiveness to social threat by manipulating attention. Personality Processes and Individual Differences. 2007;93:651–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kazdin AE, Blase SL. Rebooting Psychotherapy Research and Practice to Reduce the Burden of Mental Illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:21–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]