Abstract

Post primary tuberculosis occurs in immunocompetent adults, is restricted to the lungs and accounts for 80% of all clinical cases and nearly 100% of transmission of infection. The supply of human tissues with post primary tuberculosis plummeted with the introduction of antibiotics decades before the flowering of research using molecular methods in animal models. Unfortunately, the paucity of human tissues prevented validation of the models. As a result, it is a paradigm of contemporary research that caseating granulomas are the characteristic lesion of all tuberculosis and that cavities form when they erode into bronchi. This differs from descriptions of the preantibiotic era when many investigators had access to thousands of cases. They reported that post primary tuberculosis begins as an exudative reaction: a tuberculous lipid pneumonia of foamy alveolar macrophages that undergoes caseation necrosis and fragmentation to produce cavities. Granulomas in post primary disease arise only in response to old caseous pneumonia and produce fibrosis, not cavities. We confirmed and extended these observations with study of 104 cases of untreated tuberculosis. In addition, studies of the lungs of infants and immunosuppressed adults revealed a second type of tuberculous pneumonia that seldom produces cavities. Since the concept that cavities arise from caseating granulomas was supported by studies of animals infected with Mycobacterium bovis, we investigated its pathology. We found that M. bovis does not produce post primary tuberculosis in any species. It only produces an aggressive primary tuberculosis that can develop small cavities by erosion of caseating granulomas. Consequently, a key unresolved question in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis is identification of the mechanisms by which Mycobacterium tuberculosis establish a localized safe haven in alveolar macrophages in an otherwise solidly immune host where it can develop conditions for formation of cavities and transmission to new hosts.

Keywords: Post primary tuberculosis, lung, pathology, cavity, human

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) is an obligate human parasite 1, 2. While it can infect most warm blooded animals, and is highly virulent for some, no animals can reproducibly transmit infection to others 3. Consequently, the continued existence of MTB depends on transmission among humans. Over many millennia, MTB has evolved a complex life cycle that allows it to persist indefinitely in human communities as small as a few hundred people 4. This life cycle includes two distinct types of infection: primary and post primary tuberculosis in addition to prolonged periods of dormancy. The infection typically begins with a first or primary infection that heals spontaneously with the development of an immune response. After 10 to 30 years, the organisms emerge from dormancy (or the person is reinfected) to develop post primary tuberculosis that produces cavities in the lung that support proliferation of massive numbers of organisms that are coughed into the environment to facilitate transmission to new hosts.

Primary tuberculosis is the infection that occurs in immunocompetent people when they are first infected with MTB 5. Although it may progress causing meningitis or disseminated tuberculosis, especially in very young or immunosuppressed individuals, primary tuberculosis typically develops and spreads as caseating granulomas to regional lymph nodes and systemically for only a few weeks before regressing as immunity develops. While the lesions may heal, they are seldom sterilized and organisms persist. We have many animal models of primary tuberculosis and reasonable access to human tissues and so have made much progress in understanding the development and functions of its characteristic lesion, the caseating granuloma 6–9.

Post primary, also known as adult type or secondary, tuberculosis, in contrast, occurs in people who have developed immunity to primary tuberculosis 10–12. It differs from primary tuberculosis in the genes that modulate susceptibility, clinical presentation, complications and age distribution of hosts 13. Post primary tuberculosis is typically restricted to the upper lobes of the lungs and does not involve lymph nodes or other organs. About 90% of cases recover spontaneously without therapy. However those that become ill account for 80% of all clinical cases and nearly 100% of transmission of infection. The inability to resolve post primary tuberculosis is not due to inadequate systemic immunity because the victims are solidly immune to infection in their entire bodies except for localized portions of the lung. In fact, the persons most likely to die from acute post primary tuberculosis are immunocompetent young adults ages 15–40 with strong tuberculin specific cell mediated immune reactions 10, 14–16. Those who survive the acute process are likely to be left with a cavity in a lung that spews massive numbers of organism into bronchi that are coughed into the environment over a period of decades, but fail to produce disease in any other part of the body. Post primary tuberculosis does not confer immunity. It does the opposite. People who have recovered from post primary tuberculosis naturally or through treatment have much higher risk than others in their communities of developing the disease again 1, 17, 18. The recurrent disease frequently results from new infection from the environment, not from reactivation of the first infection. We know very little about the mechanisms of post primary tuberculosis.

The pathology tuberculosis was described in the 19th and early 20th centuries with two major components termed ‘productive’ and ‘exudative’ 19–21. In 1821, Laennec, using clinical and gross pathologic observations, reported that primary and post primary TB were distinct manifestations of the same disease 22. A half century later with the introduction of microscopes, Virchow disputed this and claimed that they were totally different diseases 23. He reported that primary tuberculosis was a tumor while post primary was an infection. This argument was resolved by Koch’s discovery of the causative organism. However, Koch observed that second exposure to MTB produces a fundamentally different disease than the first1, 2. From the 1880’s until the 1950’s many authors described the two different histologic patterns of tuberculosis using diverse nomenclatures 19, 20, 24, 25. Productive lesions or tubercles are granulomas, especially caseating granulomas. Exudative lesions are tuberculous pneumonia. Each occurred in multiple variations and progressed through a series of stages. It is unlikely that many important features of the pathology of tuberculosis were not described. However, studies of the pathology of post primary tuberculosis effectively ended when interest in the disease and availability of human lung tissues plummeted with the introduction of antibiotics in the 1950’s. Interest in tuberculosis revived decades later with the realization that the disease had not been eradicated and the rise of modern immunology and molecular biology provided powerful new methods to study it.

Using animal models, these new sciences have greatly expanded understanding of tuberculosis. However, the lack of appropriate human tissues for study made it impossible to validate the animal models. Many species develop caseating granulomas when infected with MTB and some, like rabbits infected with Mycobacterium bovis, develop caseating granulomas that erode into bronchi to produce cavities 26–28. However, MTB is an obligate human pathogen because it can complete its life cycle only in humans. No other species, under natural conditions, develops the lesions necessary for transmission of infection. The far more complex pathologic descriptions of human pulmonary tuberculosis in the older literature were forgotten amidst the excitement of rapid scientific advances centered on granulomas. In addition, the insistence by many reviewers that animals be infected with small numbers of bacilli by aerosol to produce physiologic infections further restricted the spectrum of models available for study 11, 27. As a result, virtually the entire contemporary literature describes caseating granulomas as the characteristic lesion of all tuberculosis. Models are judged to be “human like” based on their ability to produce caseating granulomas 11, 19, 29. It is a paradigm of contemporary research that cavities form when caseating granulomas erode into bronchi and discharge their softened and liquefied contents into the airways 9, 25, 30. This simplified mechanism that ignores the existence of exudative reactions has guided the research on post primary tuberculosis for generations of investigators.

We previously reported studies of tissues from several people with untreated primary and post primary tuberculosis that contradicted this paradigm 31. We rediscovered observations from the preantibiotic era that post primary tuberculosis begins as an exudative reaction with infection of foamy alveolar macrophages. The infection progresses to caseous pneumonia that undergoes fragmentation and softening to produce cavities. There were no active granulomas of any kind in these lungs. Caseating granulomas appeared to be characteristic of primary tuberculosis and to play no part in the development of cavities.

In continuing studies, we have examined tissues of over 100 patients with untreated and a few with inadequately treated pulmonary tuberculosis and have reviewed the literature from the preantibiotic era in an effort to refine and extend previous observations. The conclusion is that developing post primary tuberculosis is not a granulomatous disease. It is an exudative reaction, a type of pneumonia that develops in people with sufficient immunity to heal all granulomas. Granulomas do develop in post primary tuberculosis, but only as a late phenomenon that has virtually no role in the development of cavities. As Canettti reported, granulomas do not precede caseation in post primary tuberculosis, but follow it and are typically located at the periphery of the caseum. Moreover, caseum associated with a granuloma is always old and free of nuclear debris. “These two facts established that the caseum precedes the granuloma in the adult lung” 21.

Additional studies looked for exceptions to the typical pathologic patterns of post primary tuberculosis. Studies were made of slides of the lungs of infants who were to young to have developed immunity to primary tuberculosis and immunosuppressed adults with HIV and other conditions. We found no evidence that pulmonary cavities ever arise from expansion of caseating granulomas or liquefaction of their contents. All cavities were observed to arise from necrosis of tuberculous pneumonia, frequently in persons with no caseating granulomas in their entire bodies.

This manuscript reviews pathology of each of the stages of post primary tuberculosis: how it begins, regresses or progresses to cavitation and/or fibrocaseous disease. Most post primary tuberculosis regresses spontaneously leaving only small scars in the apex of the lung 1, 2, 32. Those that do not regress typically undergo rapid necrosis to produce cavities. Once formed, cavities can either stabilize and become nearly asymptomatic indefinitely or they can produce chronic relapsing or progressive fibrocaseous disease that results in extensive necrosis and fibrosis. Finally, we asked how the misconceptions of the contemporary literature arose. A review of the literature revealed two additional points. The first was failure to appreciate the differences between infections produced by M. bovis and MTB and the second was misinterpretation of a hypothesis that caseating granulomas seeded tuberculous pneumonia to infer that they directly caused cavities.

With the realization that post primary tuberculosis begins as an infection of alveolar macrophages in people with sufficient immunity to heal caseating granulomas, the key unresolved question of adult tuberculosis shifts away from caseating granulomas to an understanding of how MTB subvert or evade otherwise highly effective systemic immunity to establish a privileged site within foamy alveolar macrophages in certain areas of the lung while the rest of the body remains highly immune. It is hoped that a more accurate understanding of the pathology of post primary tuberculosis may lead to more focused studies, better understanding and eventually control of the world’s most lethal bacterial infection.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UT-Houston Medical School IRB protocol number HSC-MS-10-0109, Immunopathology of Tuberculosis. We studied microscope slides of tissues from patients with tuberculosis. All materials were by products of regular surgical or autopsy practice. We were not involved in any way with collecting the tissues and had no contact with any of the patients, their families or physicians. The specimens were all treated as deidentified for the study.

Twelve cases were obtained from autopsy or surgical procedures conducted at the University of Texas-Houston Medical School. These were either lung lesions of primary tuberculosis that were clinically mistaken for cancer or autopsies of persons with disseminated tuberculosis. Fifteen cases were obtained from Medical Examiners of Galveston and Harris Counties in Texas. These were autopsies of persons with clinically asymptomatic disease that was an incidental finding or persons who died of acute undiagnosed and untreated pulmonary tuberculosis. These were particularly informative cases because they had the early stages of post primary tuberculosis with developing cavities, but did not have the later stages of caseating granulomas and fibrosis. Paraffin blocks of thirty two cases of persons who died of pulmonary tuberculosis were obtained from the First Infections Disease Hospital in St, Petersburg, Russian Federation. These demonstrated the fibrocaseous pathology typical of chronic post primary tuberculosis. Finally, forty seven cases were reviewed in the Department of Pathology of Johns Hopkins University using the Johns Hopkins Autopsy aRchive Information System (JHARIS). Search of this system for pulmonary tuberculosis yielded 2854 cases with the demographics and autopsy diagnoses. Slides were examined of cases selected for specific reasons such as age of patient, immunosuppression or autoimmune disease, and listing in Rich’s book on the pathogenesis of tuberculosis 20. Slides of rabbit tissues infected with M. bovis were obtained from the Department of Immunology at Johns Hopkins.

Slides of each case were examined in an effort to define the pattern and sequence of pathologic changes. Most immunocompetent patients who die of pulmonary tuberculosis have chronic fibrocaseous disease that has a varied and heterogeneous pathology. The availability of seldom seen specimens of both very acute disease and spontaneously resolving post primary tuberculosis as well as cases of multiple stages from the preantibiotic era made it possible to reconstruct the sequence of pathologic changes with confidence.

Results

Primary tuberculosis

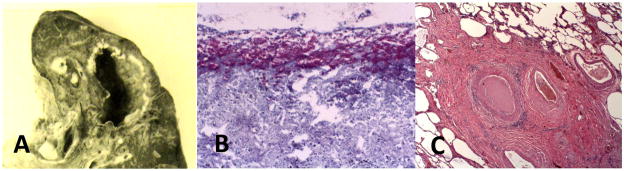

Primary tuberculosis occurs in previously uninfected individuals with competent immune responses2, 6. The characteristic lesion, a caseating granuloma, is a localized lesion in tissue consisting of a central area of caseous necrosis surrounded by epitheloid macrophages and then lymphocytes, Figure 1. Caseation necrosis was termed ‘fatty metamorphosis’ by Virchow because it contains abundant lipid and foamy macrophages 9, 23, 33. Caseation is a process of coagulation necrosis in which lipid rich cells disintegrate and are converted into a homogeneous, structure less mass devoid of blood vessels 19, 23, 34. Caseating granulomas may enlarge and progress, but rarely exceed two to 3 cm in diameter. Their centers may undergo calcification and heal with fibrosis and scarring. Organisms are contained and constrained within caseating granulomas, but not all are killed 6. These lesions are characteristic of the first infection tuberculosis that heals to form a Gohn complex with calcified granulomas in the lung and hilar lymph nodes. The histologic appearance of caseating granulomas is similar in all of their occurrences including primary infections in the lung and secondary spread as tuberculomas that may occur in bone, brain, kidney, lymph nodes or other organs, in miliary tuberculosis and in late stages of post primary tuberculosis19, 20.

Figure 1. Caseating granulomas of primary tuberculosis.

A central core of necrotic lipid rich material is surrounded by foamy macrophages, epitheloid macrophages and lymphocytes. Three examples of caseating granuloma are shown: (A) shows an early caseating granuloma in the lung of a person with miliary tuberculosis (H & E Stain 100× Magnification). (B) A cluster of caseating granulomas that was mistaken for a cancer and surgically removed. Cuffs of blue staining lymphocytes surrounding caseous necrotic material are particularly evident (H & E Stain 1× Magnification). (C) An older lesion in a human lung showing fibrous capsule and necrotic center. Epitheloid cells and a giant cell (arrow) indicate that it is still active (H & E Stain 100× Magnification).

Post-primary tuberculosis

Post-primary (adult type) tuberculosis develops preferentially in people with sufficient immunity to clear and heal caseating granulomas of primary tuberculosis. Post primary tuberculosis is typically restricted to the upper lobes of the lung with no evidence of infection in any other part of the body. While there were many debates in the pathologic literature of the preantibiotic era, many reports since Laennec in 1821 agreed that post primary tuberculosis begins as a pneumonic rather than a granulomatous process 12, 19–22, 24, 34. We found no exceptions to Rich’s assertion that “It has been found by all who have studied early human pulmonary lesions that they represent areas of caseous pneumonia rather than nodular tubercles” 20. Canetti wrote “The important concept is that the exudative reaction is at the beginning of every (post primary) tuberculous lesion.” Granulomas develop around old caseous pneumonia and contribute to healing and/or fibrosis. Subsequent aggravation of the disease may lead to caseating granulomas in the lung, but they seldom, if ever, contribute to the formation of cavities 21.

Lipid pneumonia phase

Post primary tuberculosis begins with accumulation of foamy macrophages in alveoli in localized areas of the lung, typically near the periphery of an upper lobe, Figure 2 19, 35, 36. Acid-fast organisms are present (~1–2/high power field) almost exclusively in alveolar macrophages 21. There are no leukocytes or fibrin and little edema in these lesions 21. The lesions of early pulmonary tuberculosis can develop along several pathways. About 90% of regress spontaneously leaving only small scars in the apices of the lungs 10, 19, 24. The term epituberculosis was used to describe tuberculous pneumonia that resolved spontaneously 37, 38. Scars of such healed lesions were found in the apices of the lungs of the majority of people in Europe and the U.S. who were born in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The numbers of AFB typically decline as alveoli become variably filled with fibrin, cell debris, red blood cells and leukocytes in addition to alveolar macrophages. In some areas, foamy macrophages accumulate additional lipid that largely fills the alveoli. Many of the foamy macrophages have been reported to be positive for the dendritic cell marker DEC-205 39.

Figure 2. Histopathology of developing post-primary tuberculosis.

(A), Initially, the alveoli are filled with macrophages while the alveolar walls have increased numbers of lymphocytes. The macrophages are foamy due to accumulation of lipid. Such lesions may develop in several ways. In some areas (B), the cellular debris and fibrin predominate. In others, (C) the macrophages become increasingly lipid rich. Langhans giant cells may be found (D). Eventually, many cells within the alveoli undergo caseation necrosis (E). The process may involve larger areas of the lung or single alveoli. Most such lesions may spontaneously resolve with replacement of alveolar cells with fibrin and fibrous tissue (F). Resolving lesions eventually form fibrous scars in the apices of lungs (H & E Stains 100 to 400× Magnification).

Endobronchial tuberculosis producing bronchial obstruction is a constant feature of developing post primary tuberculosis in both the pathologic and radiologic literatures 10, 40, 41. The earliest radiological feature is the “tree-in-bud” pattern on CAT scans, Figure 3 42–45. Infected cells and debris fill small bronchi to produce the ‘tree-twig component seen 42, 43, 45. Foci of adjacent alveoli become filled with foamy alveolar macrophages and lipoid debris to from the “buds”. Alveolar macrophages become increasingly foamy and then degenerate leaving lipoid debris and rare acid-fast bacilli in alveoli 33. This produces the ground glass appearance on radiographs 44, 46. These lesions may slowly progress for a period of a year or more producing little or no clinical illness 12, 19, 24.

Figure 3. Bronchial occlusion in post-primary tuberculosis.

‘Tree and bud’ pattern is the characteristic CAT scan appearance of early post-primary tuberculosis 43, 45 (A). The tree twigs in the radiograph are bronchi filled with infected cells and debris while the buds are areas of tuberculous pneumonia in alveoli. The section (B, C) shows a bronchi occluded by such material. Bronchial obstruction has been reported by many authors in 100% of cases of post-primary pulmonary tuberculosis 10, 20, 40, 41 (H & E Stain 100× Magnification)

Endobronchial tuberculosis has usually been interpreted as evidence of spread of infection through the lung via bronchi 20. We favor an alternative explanation that bronchial obstruction is an essential component of developing post primary tuberculosis. Bronchial obstruction by cancer or other mechanical means causes an endogenous lipid pneumonia known as ‘golden pneumonia’ due to a yellow color imparted by high lipid content 47, 48. Histologically, golden pneumonia may be quite similar to lipid rich tuberculous pneumonia. It may even undergo necrosis and produce cavities. Furthermore, opening obstructed bronchi has been reported to cause resolution of post primary tuberculosis 20. Consequently, it is likely that endobronchial tuberculosis is an important component of the pathogenesis of early post primary tuberculosis.

Caseous pneumonia

The lipid pneumonia lesions that do not heal eventually undergo necrosis to produce caseous pneumonia 10, 12, 21, 22. Caseation is necrosis characterized by cloudy swelling and homogenization occurring in the absence of any cellular influx. It begins as an exudate in which fibrin loses its fibrillary structure, swells, becomes homogeneous and fills the entire alveolus, Figure 2E. The alveolar cells lose their contour, their protoplasm is destroyed, their nuclei become pyknotic and then are obliterated. Necrosis soon involves the alveolar septa that lose their capillaries but retain elastic fibers. The vessels and bronchi eventually undergo the same fate and the mass of necrosis assumes an absolutely homogeneous character.

The onset of caseation necrosis is frequently associated with an explosive increase in numbers of AFB 21, Figure 4. AFB, usually single organisms, are found in fewer than only 5% of alveoli that contain viable macrophages. However, most cells in alveoli near areas of caseation necrosis contain prominent mycobacterial antigen assessed by immuohistochemistry 31, 39. This suggests that an accumulation of mycobacterial products within alveolar macrophages precedes the onset of caseation necrosis. The numbers of AFB decline with aging of the caseous material in a fashion similar to that observed with caseating granulomas. The increase in numbers of AFB with onset of caseation does not occur in all cases. In some instances, typical caseation develops without any demonstrable increase in AFB.

Figure 4. Distribution of AFB and mycobacterial antigen in post primary TB.

Very few AFB are found in foamy alveolar macrophages of developing post primary tuberculosis. Their numbers increase markedly with the development of necrosis. (A) Section of lung showing masses of AFB in an alveolus with caseous necrosis, but not in adjacent viable alveoli (acid fast stain 40X). (B). High magnification of AFB associated with necrotic cells and debris (acid fast stain 400X). (C) A single AFB in a viable macrophage (acid fast stain 400X). (D) Demonstration of abundant mycobacterial antigens in viable cells that have no AFB (Immunohistochemical stain for MTB 400×).

Production of cavities

Areas of caseous pneumonia, especially larger ones, eventually undergo softening and fragmentation. The necrotic mass becomes fissured and fragmented into large clumps usually without any evidence of new cellular elements. Tuberculosis is usually a slowly developing chronic disease, but it can change rapidly. In acute cases, the caseation, softening and fragmentation can occur simultaneously 10, 22. In a typical example, a previously healthy 60-year-old woman died following a two-week febrile illness with chest pain. Her lungs demonstrated tuberculous lipid pneumonia with patchy caseation and developing cavities, Figure 5A. There were no active granulomas anywhere in her body. There were scars of healed granulomas, but they contained no epitheloid cells, giant cells or caseation. The cavities were formed by acute necrosis of large sections of lung with tuberculous lipid pneumonia. The necrosis was also associated with vasculitis as has been frequently reported, Figure 5B 20, 25, 34.

Figure 5. Formation of Cavities.

In its classic occurrence, tuberculous cavities form rapidly following onset of acute febrile pneumonia. (A) A developing cavity containing necrotic lung tissue. The wall of the cavity is composed of a layer of necrosis overlying lipid pneumonia. The cavity contains fragments of necrotic lung (Arrows) (H & E Stain 4× Magnification). This lung was positive for MTB by PCR and AFB even though the number of organisms was small. (B) Vasculitis in a small artery in the lung. The vessel wall is thickened, vacuolated and infiltrated with lymphocytes. The lumen is largely occluded (H & E Stain 100× Magnification). (C) Necrotic lung tissue within a bronchus of a person with acutely developing cavitary tuberculosis (H & E Stain 40× Magnification).

Cavities form when the softened and fragmented lung is coughed out. This destruction of lung can produce massive bleeding as the first clinical sign of tuberculosis 10, 21, 49. Actual fragments of necrotic lung may be seen in the bronchi where they were in the process of being coughed up, Figure 5C. Staining of sputum for such fibers was a valuable test used to distinguish tuberculosis from ordinary pneumonia 50, 51. Cavities are irregular at first, but soon become more regular due to further discharge of necrotic lung and compensatory mechanisms. AFB are present only in very small numbers in such lesions during and immediately after cavity formation. This is a common presentation where the entire process of cavity formation is an acute pneumonia like illness that lasts for 1–2 weeks before resolving leaving a cavity in the lung 10, 12, 22.

This pattern of cavity formation by necrosis and fragmentation of caseous pneumonia was observed in every case that had a cavity. We found no evidence that pulmonary cavities ever form by erosion of caseating granulomas into bronchi. In fact, there were no caseating granulomas in the lungs of any of the cases of acute cavity formation that we examined. This is consistent with numerous reports in the literature from the 1820s through the 1960s 10, 20, 22, 24, 34, 40.

Maturation of cavities

While resolution of untreated post-primary tuberculosis is common prior to the formation of a cavity, it is rare after cavity formation 10, 12. Tuberculosis frequently resolves in all parts of the body except for a thin walled cavity that produces vast numbers of organisms over a period of decades. Such individuals are the primary transmitters of infection to the community. Even today many appear healthy with no clinical signs of tuberculosis 52.

Newly formed cavities contain very few AFB. Over time, they develop a thin wall of fibrosis lined by a layer of necrotic material. Organisms then grow in massive numbers on the surface of the cavities. The mature cavity has been described as an area of failed immunity 53. This may be related to an increased concentration of Foxp3 positive Treg cells 39. In a characteristic case, large numbers of acid-fast organisms were visible extracellularly lining the surface of the cavity while all other lesions in the lung had healed leaving inactive scars with no demonstrable organisms, Figure 6. Infection was confined to the wall of the cavity while the rest of the body had no caseating granulomas, tuberculous pneumonia or any other manifestation of active disease. The wall of the cavity consisted of a thin layer of caseous necrotic tissue surrounded by fibrosis with little inflammation, epitheloid and giant cells. Instead there is granulation tissue rich in capillaries lymphocytes and fibroblasts. Collagenous fibers are welded into a ring to form a capsule. Such capsules continue to thicken with collagen fibers 21.

Figure 6. Maturation of Cavities.

Cavities frequently develop as thin walled structures with little inflammation and masses of organisms growing as a pellicle on the inner surface. (A) A cavity in the upper lobe of the lung with connection to a bronchus. The disease was largely asymptomatic and the patient died of unrelated illness. The wall of the cavity was composed of fibrous tissue and a layer of necrotic debris. (B) The surface demonstrated massive numbers of acid-fast organisms (acid-fast stain 200X). No organisms or evidence of active tuberculosis were present anywhere else in the body. (C) Other areas of the lung demonstrated scars of healed tuberculosis with no evidence of recent activity (H & E Stain 100× Magnification).

Laennec provided an especially clear description of such cavities 22. ‘Some patients develop empty cavities, lined by membrane, that persist for years with minimal symptoms other than cough. Such subjects refer the origin of their cough to a violent pneumonic disease that made their case, at the time, be considered desperate. The ‘membranes’ lining of such cavities were non-washable, semitransparent, grayish white, with a texture like that of cartilage, but somewhat softer, adhering closely to the pulmonary tissue and forming a complete lining of the cavity. The membrane is generally quite perfect, covering the whole internal surface of the cavity. It is apt to be detached and discharged in the sputum. Cavities with such membranes are entirely empty. All such cases that Laennec examined died of unrelated diseases. They had all lived for years in a ‘very supportable state of health’, being merely subject to chronic cough.

Laennec’s description of the membranes lining such cavities is that of a pellicle that forms when virulent MTB are cultured the surface of liquid media 54. This is consistent with the observation that organisms grow in massive numbers on the surface of the cavity, but not in any other part of the body, Figure 6B. These people are most dangerous for spreading infection to others. They usually live in good health for decades coughing large numbers of organisms into the environment, but their infection remains localized on the surface of the cavity and never spreads to other parts of the body.

Healing and chronic fibrocaseous tuberculosis

In some cases, the caseous necrotic material does not disintegrate but remains intact in a cheesy mass, Figure 7A–C. In this case, a large section of the upper lobe is dead and colored white. Histologically, it was a necrotic caseous pneumonia. Viable lung with tuberculous lipid pneumonia was present around the edges. Again there were no caseating granulomas or epitheloid cells in sections of this lung. The entire lesion consisted of various stages of lipid pneumonia and caseous pneumonia.

Figure 7. Chronic fibrocaseous tuberculosis.

Masses of caseous pneumonia that do not soften and fragment to produce cavities may simply persist in a relatively inactive state. In this case, a necrotic upper lobe of the lung with caseous pneumonia has become mummified (A). Microscopically it consists of caseous pneumonia adjacent to viable areas of lipid-rich tuberculous pneumonia (B,C) (H & E Stain 100–400× Magnification). More often the aging caseous pneumonia becomes surrounded by granulomatous tissue (D). The central necrotic core retains the structure of alveoli with caseous pneumonia that is surrounded by an active granulomatous process with epitheloid cells, giant cells and lymphocytes, but no foamy macrophages. Fibrosis surrounds smaller areas of caseous pneumonia (E) or extends across large areas of lung with larger lesions to produce pulmonary fibrosis (F). Multiple layers of fibrosis demonstrate that the lesion has progressed and regressed on multiple occasions (G). (Trichrome Stains 40× Magnification). Rarely, erosion of caseating granulomas into cavities is seen (G). However, the lesions are always small and it is seldom clear whether the cavity eroded into the granuloma or visa versa.

While caseating granulomas are not present during the formative stages of post-primary tuberculosis, they do develop during chronic disease, appear to be part of a healing process and to be responsible for extensive fibrosis. Small areas of old inactive appearing tuberculous pneumonia are typically surrounded by granulomas with epitheloid cells, giant cells and lymphocytes, Figure 7D. Such lesions may heal to leave only fibrous scars. In the case of large areas of caseous pneumonia, tubercle formation begins at the periphery of the caseation and has a similar appearance, but progresses to fibrocaseous tuberculosis 21, Figured 7 E–F. It is common to find multiple concentric rings of fibrous tissue suggesting that the lesions have progressed and then healed on multiple occasions. This pattern of caseating granulomas developing as part of the chronic or healing process of post primary tuberculosis was clearly described by Ewart in the Gulstonian’s lectures of 1882 as well as by subsequent authors 20, 21, 55. Caseating granulomas are occasionally observed opening into cavities, but they are at most a minor component compared to fragmentation of caseous pneumonia, Figure 7G.

Most clinical and autopsy cases of post-primary tuberculosis are chronic fibrocaseous disease 20. In such people, the production of caseous pneumonia continues after formation of cavities and produces a complex mixture of multiple patterns of lipid pneumonia, caseous pneumonia, new cavity formation, fibrosis, caseating granulomas and healing. In a typical case, some areas show the dry fibrinous exudate of a chronic inactive caseous pneumonia while adjacent areas contain active caseous pneumonia with new cavity formation. The fibrosis tends to worsen over time. Such lesions are the leading cause of pulmonary fibrosis worldwide that cause collapse, emphysema, fibrosis, sclerosis and atelectasis 21, 56.

A long standing observation is that tuberculous lesions in the same organ may evolve in radically different manners and appear to behave independently of one another 25, 57. One lesion may heal by fibrosis while another is developing new lipid pneumonia, caseation pneumonia or a new cavity 25. Nearly all stages of post primary tuberculosis are frequently found in single lungs. There is nothing that more clearly emphasizes the preeminent importance of local factors in the evolution of post primary tuberculosis 21. Such heterogeneity in stage and age of lesions is not found in primary tuberculosis, miliary tuberculosis or tuberculosis in immunosuppressed people.

Pulmonary tuberculosis in immunosuppressed people

Further studies were conducted in immunosuppressed and very young subjects in an effort to find exceptions to the rule that cavities form by necrosis and fragmentation of tuberculous pneumonia. It is well known that very young, aged or immunosuppressed people are more likely to die of disseminated tuberculosis, but are less likely to develop cavities 58, 59.

The first case was a man with HIV infection who died of rapidly progressive pulmonary tuberculosis, Figure 8A–C. He had miliary tuberculosis with caseating granulomas in his lung and many other organs. The caseating granulomas had fewer epitheloid and lymphoid cells and many more AFB that typically found in such granulomas from imunocompetent persons. In addition, he had tuberculous pneumonia with large numbers of organisms within alveolar macrophages. Large areas of the tuberculous pneumonia were undergoing necrosis to produce poorly formed cavities while the miliary lesions of caseating granulomas remained intact. Such lesions differ significantly from those that develop in immunocompetent people. They contain far more AFB, fewer lymphoid cells and no giant cells. The macrophages are smaller without the foamy, lipid rich cytoplasm characteristic of lipid pneumonia.

Figure 8. Tuberculosis in immunosuppressed people.

Case 1. (A–C) Tuberculosis associated with HIV. Multiple areas of the lung demonstrated tuberculous pneumonia in which alveoli contained macrophages with many AFB (insert) but very little lipid (A). Alveolar wall contained many lymphocytes. Large areas of the tuberculous pneumonia had undergone recent necrosis (B). Still others areas of the lung demonstrated caseating granulomas of miliary tuberculosis (C) (H & E Stain 100–400 × Magnification, Insert Acid-fast stain 1000× magnification).

Case 2 (D–F): Cavitary tuberculosis in an infant. A 9-month-old child died of rapidly progressive tuberculosis. The lung contained many caseating granulomas, large foci of tuberculous pneumonia and cavities (D arrow). The lung adjacent to the cavities contained necrotizing tuberculous pneumonia (E). The viable areas demonstrated tuberculous pneumonia with cells that contained very little lipid (F). Cavities were found exclusively in the areas of tuberculosis pneumonia, not in the nodule lesions of caseating granulomas. (H & E Stain 40–200× Magnification).

Case 3. (G–H) Tuberculosis in an immunosuppressed individual. A man with rheumatoid arthritis receiving large doses of steroids died of rapidly progressive tuberculosis. Lesions of the lung were a caseous pneumonia with few macrophages or lymphoid cells but much edema and fibrinous exudate within alveoli (G). Massive numbers of acid-fast organisms were present in the areas of acute necrosis (H) (H & E Stain 40 – 200× Magnification, Acid-fast stain 400 × magnification).

Cavities have been reported in infants who die in much less time than is required for development of typical post primary tuberculosis. Sections of such an infant demonstrated large caseating granulomas and tuberculous pneumonia 20. The cavities were due to necrosis of the tuberculous pneumonia, Figure 8D–F. The caseating granulomas had few lymphocytes and lacked typical epitheloid cells and giant cells as expected with an immune response that had not fully developed. The tuberculous pneumonia had evidence of little lipid.

A man with rheumatoid arthritis treated with steroids died with disseminated tuberculosis, Figure 8G–H. He had developed rapidly progressive pulmonary tuberculosis with caseous pneumonia. Again, poorly developed cavities were observed in areas of tuberculous pneumonia. No caseating granulomas were present.

While the cavities in each of these cases formed from necrosis of caseous pneumonia, they differ significantly from those that formed by immunocompetent individuals. Acid-fast organisms were far more abundant in the caseous pneumonia and the disease was typically generalized and not restricted to the upper lobes. Some lesions contained many neutrophils while the alveoli of others contained much acellular fibrinous material and macrophages. The macrophages were less foamy and there was little evidence of accumulation of lipid within the lesions. In no case did the cavities develop fibrous walls or support the growth of massive numbers of AFB on their surfaces as is typical of those in immunocompetent individuals. Finally, the lesions within an individual were quite homogeneous in contrast to the marked heterogeneity of age and stage of lesions found in immunocompetent adults.

Reproducibility of observations

This type of observational study is not amenable to statistical analysis. Nevertheless, the reproducibility of the observations deserves comment. The literature on the pathology of tuberculosis has never been either clear or simple. Descriptions have changed with evolving nomenclature, theories and technology. Each investigator selected observations that seemed relevant to the prevailing understanding of disease. The same is true of this paper. Nevertheless, much effort was expended to identify consistent morphologic observations among the mass of publications and available cases. Generally, Canneti’s book written at the end of the preantibiotic era is the most concise. Rich’s much longer volume is especially valuable because he included case numbers and the slides remained available so that one could see exactly what he described. A list of numbers of cases examined and pertinent references for each of the key findings of this study is presented in Table 1.

Table I. Reproducibility of key observations.

The key conclusion of this study is that cavities of tuberculosis arise by necrosis of tuberculous lipid pneumonia, not by erosion of caseating granulomas into bronchi. This table lists the number and source of cases examined and key references that support each of the relevant pathologic findings. Authors of the references described studies of many more cases. Canneti for example studied 1500 and Rich over 2000 autopsy cases of tuberculosis.

| Pathologic Finding | Number of Cases | Source of cases | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post primary TB begins as a lipid pneumonia. | 9 | 1(UT), 5(ME), 3(R) | 20, 21, 33, 35, 37, 40 |

| Bronchial obstruction is a constant finding of post primary TB. | 25 | 1(ME), 1(UT) 3 (JHU) 20 (R) | 20, 21, 40, 41, 45 |

| Cavities form by necrosis of tuberculosis pneumonia. | 15 | 4(ME), 5(JHU) 6(R) | 20, 21, 24, 40 |

| Cavities can form by sudden necrosis of tuberculosis pneumonia, | 8 | 4(ME), 3 (JHU), 1 (R) | 10, 12, 20–22, 76 |

| Cavity formation is associated with coughing up pieces of lung. | 3 | 2 (ME) 1 (JHU), | 10, 20, 51 |

| Caseating granulomas in post primary TB are a reaction to old TB pneumonia. | 8 | 1 (JHU) 7 (R) | 21, 55 |

| Infants and immunosuppressed adults develop a different kind of TB pneumonia with little lipid. | 8 | 1(UT), 6(JHU) 1(R) | 20, 58, 77 |

| MTB are confined to the surface of mature cavities. | 3 | 1(JHU), 1(ME), 1(R) | 10, 20, 21, 76 |

| Chronic fibrocaseous TB is a mixture of stages that progress and resolve independently of one another. | 34 | 2(UT), 25(R) 7 (JHU) | 20, 21, 25, 57 |

| Healing post primary produces apical scars. | 5 | UT (4), ME (1) | 20, 21, 32, 76 |

Source of cases: University of Texas-Houston (UT), Medical Examiner (ME), Johns Hopkins University (JHU), and St. Petersburg, Russian Federation (R).

Pathology of bovine tuberculosis in man and animals

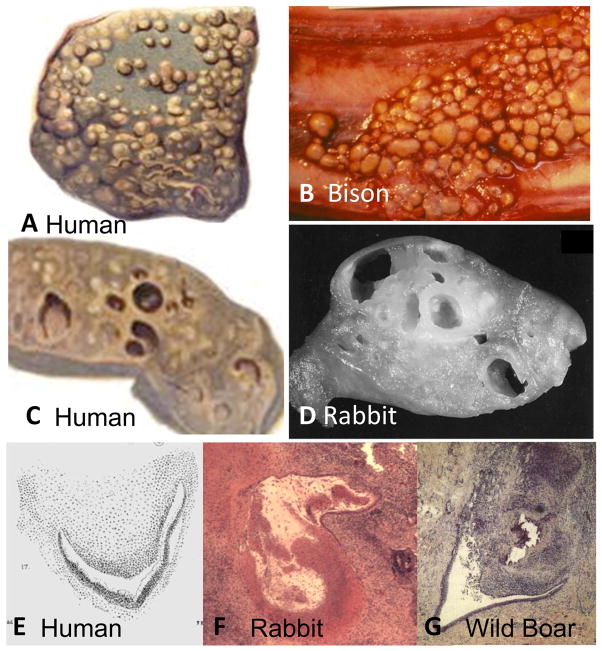

Since much of current understanding of post primary tuberculosis is based on studies of M. bovis in rabbits, we sought to investigate the pathology of bovine tuberculosis in humans and animals. We found that very little has been published. The prevention of M. bovis infection by pasteurization of milk and skin testing of animals curtailed both interest in the disease and availability of tissues for study half a century before the introduction of antibiotics curtailed specimens and interest in MTB. Recent publications describe only minimal disease 60. However, Creighton and later Francis described the pathology of bovine tuberculosis in cattle and humans 61, 62. It was called Pearls’ Disease in cattle because the lesions formed as discrete nodules (pearls) of up to 2cm in diameter on surfaces of the pleura and diaphragm in addition to within the lung, lymph nodes and other organs, Figure 9. Histologically the pearls were typical caseating granulomas. These lesions formed small cavities by softening and erosion into bronchi and other structures. Multiple lesions could coalesce to form larger cavities. Similar pathologic findings were observed in both humans and cattle infected with bovine tuberculosis. This was described as a distinct pattern of pathology as early as 1821 by Laennec 22. In his Gulstonian’s lectures of 1882, Ewart identified a subset of tuberculous cases with similar lesions that he described as “bunchy masses of pigmented fibroid tubercles.” 55. The cavities were small and formed within the grape-like nodules. Occasionally, fusion of multiple nodules produced larger cavities. Recent studies of Bovine tuberculosis in wild animals demonstrate the same picture of multiple small nodules resembling pearls or bunches of grapes that undergo central necrosis to produce cavitation 63–65. M. bovis does cause endobronchial infection and tuberculous pneumonia, but these do not contribute substantially to formation of cavities. These descriptions are remarkably similar to the pathology of M. bovis infections of rabbits that underlie current concepts of the formation of cavities, Figure 9 25. All available information is consistent with the concept that the formation of cavities by erosion of caseating granulomas is an accurate description of those formed by M. bovis, but not of M tuberculosis.

Figure 9. Pathology of M. bovis tuberculosis in humans and animals.

The characteristic lesions of M. bovis tuberculosis are nodules up to 2 cm in diameter that grow on serosal surfaces including the diaphragm, lung, and peritoneum, in addition to deep within organs. The top two figures show lesions on the pleural surfaces of a human (A) and bison (B). The lower figures show cut surfaces of cavitary lung lesions in a human (C) and rabbit (D). The cavities are caseating granulomas that have undergone central softening and erosion into adjacent structures to produce cavities.

Cavities caused by M. bovis in a human (E) rabbit (F) and wild boar (G) and have similar characteristics. Caseating granulomas have eroded into bronchi. The images of rabbit and wild boar lesions show central softening and liquefaction. The only available image of a human lesion shows similar morphology 61. (Wild boar image from Gortazar with permission 65. The rabbit slide from Converse by permission 75) (H & E Stain 40× Magnification). (Human Pictures are from Creighton, 1881 61 Bison picture from U Manitoba by permission).

Discussion

One would think that the pathology of tuberculosis would have been accurately described long ago and that the science of the 21st century would have moved far beyond morphologic descriptions. Such is not the case. Part of the problem is that, since the development of antibiotics, few pathologists have ever seen untreated pulmonary tuberculosis. They remain familiar with primary tuberculosis from examination of lymph node, bone marrow and liver biopsies. They also see autopsies of disseminated tuberculosis in immunosuppressed patients or far advanced post primary tuberculosis, but almost never early post primary tuberculosis. Surgery to remove cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis is performed in some parts of the world, but studies of such tissues have not identified the changes of early post primary tuberculosis. Several factors probably account for this. First, the patients are almost always treated with antibiotics before surgery. Antibiotics rapidly clear the pneumonia obliterating key features of the disease. This was reported by Rich and Canetti in the early days of antibiotic therapy and has been confirmed many times in the pathologic and radiologic literatures 20, 21, 66. Second, patients who undergo surgery generally have milder disease than those who die of it. One would expect autopsy studies to show more severe disease than surgical specimens. Finally, the most informative specimens were from people who died of acute tuberculous pneumonia and would not have been surgical candidates.

Another issue is the nature of the pathologic literature. Descriptions of pathologic changes are almost always intermixed with mechanistic interpretations. As far back as 1881, Creighton wrote that “The pathology of tuberculosis in man has been surrounded by so many difficulties. The interpretation of the morbid appearances and of their relation to each other, has depended so much on an ever-shifting theory of the disease 61.” In an era of rapid advances in science, both the nomenclature and focus of research change rapidly making it very hard to read older literature. This is especially true of tuberculosis because of the prolonged gap in research precipitated by the introduction of antibiotics. When interest revived a generation later, older investigators had left the field and the focus was on new fields of immunology and molecular biology. In the absence of human tissues, investigators worked on animal models and gradually convinced themselves that they reproduced the human disease.

There was little resistance to accepting cavities in rabbit lungs produced by M. bovis as a model of post primary tuberculosis. Many investigators has proposed that erosion of granulomas into bronchi released organisms that seeded tuberculous pneumonia 20. Later investigators misinterpreted this as evidence that cavities arise directly from eroding caseating granulomas 25. In addition, it was believed that the pathologies produced by MTB and M. bovis were identical. Rich stated so in his book 20. However, there is not a single case of infection with M. bovis identified in his collection of over 30,000 autopsies at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. This is understandable because before the advent of molecular techniques, inoculations of multiple species of animals were required to identify M. bovis. This was seldom done. In addition, the introduction of pasteurization of milk had greatly reduced M. bovis infection of humans and the practice of slaughter of skin test positive cattle had similarly curbed the infection in livestock. Consequently, Rich’s investigations were conducted 40 or more years after infection with M. bovis had ceased to be a significant human or veterinary health problem in the eastern United States. It seems that in the absence of appropriate tissues to examine, he accepted prevailing concepts of the pathology of M. bovis just as modern investigators accept the concept that cavities arise from caseating granulomas.

With the introduction of Google Books, the literature on the pathology of infection with M. bovis is more accessible now than at any time in the past. Cavities produced by M. bovis in all species including man arise as Lurie described by erosion of caseating granulomas into bronchi or other surfaces 26. They are seldom larger than 2–3 cm unless multiple ones fuse to produce the pattern of a bunch of grapes. This is a particularly aggressive manifestation of primary tuberculosis. There is no evidence that in the clinical or pathologic literature M. bovis is capable of producing post primary tuberculosis 62–64. Yet, concepts based on M. bovis dominate the literature on human tuberculosis.

The differences between the pathologies of MTB and M. bovis can be explained by the natural histories of bovine and human tuberculosis. Both MTB and M. bovis are obligate pathogens. Neither can survive outside of the bodies of their hosts. In typical endemic areas, MTB infects children, becomes dormant for 10 to 30 years before reactivating to produce post primary tuberculosis with cavities that spread the infection to new hosts. While M. bovis infects some long lived animals, it is endemic in cattle and deer. M. bovis must escape to find new hosts within the 2–8 years lifespan of a cow. While there is heterogeneity among lesions and they may be chronic, M. bovis does not become dormant. A single skin test positive cow in a heard will regularly infect the entire heard within a few months 62. Cattle infected with M. bovis may shed organisms from every orifice. The lungs, pharynx and esophagus through saliva and coughing, the intestine through manure, the kidneys and bladder through urine and the mammary glands though milk. The organisms spread widely through the body and form caseating granulomas that erode into any available surface to facilitate escape of organisms into the environment. MTB, in contrast, has a very different means of escaping its host to infect new people. MTB is less virulent than M. bovis in most studies and is less virulent for humans than it is for many other species 28, 25. MTB is most successful when it infects a child, hides for decades before inducing a cavity in the lung of a person with sufficient immunity to prevent infection in every other part of the body. Such a person may live for decades expelling infectious organisms into the community without ever becoming seriously ill. In several studies, half of the people who expectorate virulent MTB from cavitary tuberculosis have no symptoms of disease and deny that they even have a cough 22, 52. Post primary tuberculosis is a very effective adaption of MTB to the longevity and life styles of its host, people. It is an obligate human parasite not because it is especially virulent for people, but because no other species can support its transmission from host to host.

Reactivation of tuberculosis has long perplexed investigators. It is usually attributed to immunosuppression. While it is clear that immunosuppression can produce disseminated infection, its role in post primary tuberculosis is uncertain. Post primary tuberculosis occurs most frequently and most severely in immunocompetent young adults with strong tuberculin specific immune responses 10, 15, 16. The immunosuppressed and aged develop disseminated disease, but are less able to localize the infection to the lungs and produce cavities that spread infection to others 10. We now know that post primary tuberculosis can result from either reactivation of dormant organisms or reinfection from the environment 67. Transient immunosuppression due to trauma, other infection or malnutrition may produce reactivation of dormant organisms that seed the infection. However, once the organisms find their niche in post primary disease they evade and then subvert strong host responses. MTB needs strong host responses to insure its survival. Immunosuppression is detrimental to the organism’s ability to induce cavity formation and escape to infect new subjects.

These observations are consistent with the hypothesis of North that post-primary tuberculosis depends upon a local defect in alveolar macrophages. They accumulated lipids to become foamy and provide a safe haven for organisms in an otherwise immune host 11. Key questions for research are how does MTB establish a sanctuary within alveolar macrophages of an immune host where it can establish the conditions for caseous pneumonia and production of cavities? While much remains unknown, there are several clues. First, bronchial obstruction produced by any means including cancer is sufficient to produce lipid pneumonia 47. The condition is called golden pneumonia because the high content of lipid in tissue gives it a yellow color. Such obstructive pneumonia can undergo necrosis to produce cavities and fibrosis with some resemblance to tuberculosis. Surgical opening of obstructed bronchi has been reported to cause resolution of pulmonary tuberculosis in people and bronchial obstruction is associated with development of tuberculous pneumonia 20, 37, 68. Second, mycolic acids of MTB cause alveolar macrophages to accumulate lipid, become foamy and reduce their ability to kill ingested organisms 69. Finally, recent studies have demonstrated differences between the markers on macrophages and lymphocytes in primary and post primary tuberculosis 39.

Another question is why cavities form abruptly and why they fail to heal. We published data that the ability of a lipid, trehalose 6,6′ dimycolate (TDM), to switch between two sets of biologic activities may be key in these processes 70. While it is on the surface of MTB, TDM protects the organisms from killing by macrophages and limits the immune response. If it comes off of organisms and associates with lipid surfaces of sufficient size, TDM becomes a T cell immunogen that is highly toxic for macrophages 71. We proposed that mycobacterial products and host lipids slowly accumulate in alveoli until they reach a critical concentration to activate the toxicity of TDM to cause rapid necrosis and cavity formation 70, 72.

The relevance of animal models for post primary tuberculosis deserves comment. In most publications, the perceived relevance of animal models is based on the authors understanding of the human disease which we believe was significantly flawed. Animal models provide useful hypotheses and certain facts not observable in man, but in no case can they replace observations in man for ultimate understanding of the disease in human beings 21. MTB is an obligate human parasite because humans are the only species that can transmit infection to others under natural conditions. This transmission is most efficiently mediated by mature cavities in the lung. No animals are known to produce such cavities. Nevertheless, animals do develop lesions that are similar to most of the earlier stages of infection. There are many animal models of caseating granulomas 28. We reported that slowly progressive pulmonary tuberculosis in mice is a model of early stages of post primary tuberculosis 31. The finding of mycobacterial antigen in foamy macrophages is additional evidence for the validity of this model 73, 74. Such exudative lesions with foamy macrophages are found in several species including mice, rats and monkeys, but they are usually dismissed as nonspecific rather than as models of developmental stages of post primary disease 3. Chronic lesions in primates contain a heterogeneous mixture of lesions that may be models of chronic fibrocaseous tuberculosis 27, 57. We are rapidly developing the tools for precise and quantitative immunologic and molecular studies on fixed human tissues. It is hoped that, guided by a better understanding of pathology, these tools may be used to identify animal models of particular stages of the disease and eventually to understand and control tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the late Dr. Jerome Smith of Galveston, Texas for much advice and case materials from the Galveston County Medical Examiners Office. We are similarly indebted to Dr. Louis Sanchez, the Harris Count Medical Examiner for access to slides of tissues with tuberculosis. Dr. Vadim Karev of First Infectious Disease Hospital, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation gave us paraffin blocks of autopsy lung tissues. The late Dr Grover Hutchins of Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology provided us access to their historical collection. Finally, Drs. Paul Converse, Arthur Dannenberg, Gueno Nedeltchev, and William Bishai of the Department of Medicine of Johns Hopkins provided access to slides of rabbits infected with M. bovis. (supported in part by USPHS grant NIH HL068537 and NIAID contract NO 1-AI.30036).

Footnotes

Competing interests: No confl

References

- 1.Dubos R, Dubos G. Tuberculosis, Man, and Society. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univesity Press; 1987. The White Plague. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garay S. Pulmonary Tuberculosis. In: Garay WRS, editor. Tuberculosis. Chapter 32. Boston: Little Brown & Co; 1996. pp. 373–412. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leong FJ, Dartois V, Dick T. A Color Atlas of Comparative Pathology of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. New York: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath JW. Social networks of disease spread in the lower Illinois valley: a simulation approach. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1988;77:483–96. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330770409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donald PR, Marais BJ, Barry CE., 3rd Age and the epidemiology and pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Lancet. 2010;375:1852–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paige C, Bishai WR. Penitentiary or penthouse condo: the tuberculous granuloma from the microbe’s point of view. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:301–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter RL, Olsen M, Jagannath C, Actor JK. Trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate and lipid in the pathogenesis of caseating granulomas of tuberculosis in mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1249–61. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis JM, Ramakrishnan L. The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell. 2009;136:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell DG, Cardona PJ, Kim MJ, Allain S, Altare F. Foamy macrophages and the progression of the human tuberculosis granuloma. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:943–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osler W. The principles and practice of medicine. Chapter 26. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1892. Tuberculosis; pp. 184–255. [Google Scholar]

- 11.North RJ, Jung YJ. Immunity to tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:599–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine ER. Classification of reinfection pulmonary tuberculosis. In: Hayes E, editor. The Fundamentals of Pulmonary Tuberculosis and its Complications for Students, Teachers and Practicing Physicians. Chapter 7. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1949. pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcais A, Fieschi C, Abel L, Casanova JL. Tuberculosis in children and adults: two distinct genetic diseases. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1617–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawn SD, Acheampong JW. Pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: factors associated with mortality at a Ghanaian teaching hospital. West Afr J Med. 1999;18:270–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheeseman EA. The age distribution of tuberculosis mortality in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 1952;21:15–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korzeniewska-Kosela M, Krysl J, Muller N, Black W, Allen E, FitzGerald JM. Tuberculosis in young adults and the elderly. A prospective comparison study. Chest. 1994;106:28–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Boon S, van Lill SW, Borgdorff MW, Enarson DA, Verver S, Bateman ED, Irusen E, Lombard CJ, White NW, de Villiers C, Beyers N. High prevalence of tuberculosis in previously treated patients, Cape Town, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1189–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1308.051327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rie A, Warren R, Richardson M, Victor TC, Gie RP, Enarson DA, Beyers N, van Helden PD. Exogenous reinfection as a cause of recurrent tuberculosis after curative treatment. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1174–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunn FD. Tuberculosis. In: Anderson WAD, editor. Pathology. 4. St Louis: C.V. Mosby Company; 1961. pp. 243–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rich A. The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis. 2. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canneti G. Histobacteiology and its bearing on the therapy of pulmonary tuberculosis. New York: Springer Publishing Compani Inc; 1955. The tubercle bacillus in the pulmonary lesion of man. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laennec R. A treatise on diseases of the chest in which they are described according to their anatomical characters, and their diagnosis established on a new principle by means of acoustick instruments. T&G Underwood; London: 1821. (reprinted 1979 by The Classics of Medicine Library. Birmingham AL) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virchow R. Cellular Pathology as based upon physiological and pathological histology. London: John Churchill; 1860. (reprinted by The Calssics of Medicine Library, 1978, Birmingham, AL.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pagel W, Simmonds F, MacDonald N, Nassau E. In Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Bacteriology, Pathology, Management, Epidemiology and Prevention. Chapter 3. London: Oxford University Press; 1964. The Morbid Anatomy and Histology of Tuberculosis, An Introduction in Simple Terms; pp. 36–63. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dannenberg AM., Jr . Insights from the rabbit model. Washington, DC: ASM press; 2006. Pathogenisis of human pulmonary tuberculosis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lurie M, Abramson S, Heppleston A. On the response of genetically resistant and susceptible rabbits to the quantitative inhalation of human type tubercle bacilli and the nature of resistance to tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1952;95:119–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.95.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helke KL, Mankowski JL, Manabe YC. Animal models of cavitation in pulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flynn J, Cooper A, Bishai W. Animal Models of Tuberculosis. In: Cole STKE, McMurray DN, Jacobs WR, editors. Tuberculosis and the Tubercle Bacillus. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2005. pp. 547–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Russell DG, Barry CE, 3rd, Flynn JL. Tuberculosis: what we don’t know can, and does, hurt us. Science. 2010;328:852–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1184784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dannenberg AM., Jr Roles of cytotoxic delayed-type hypersensitivity and macrophage-activating cell-mediated immunity in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Immunobiology. 1994;191:461–73. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter RL, Jagannath C, Actor JK. Pathology of postprimary tuberculosis in humans and mice: contradiction of long-held beliefs. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87:267–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davson J. The early stages of apical scar development. The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 1939;49:483–90. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pagel W, Pagel W. Zur Histochemie der Lungentuberkulose, mit besonderer Berucksichtung der Fettsubstanzen und Lipoide. (Fat and lipoid content to tuberculous tissue. Histochemical investigation) Virchows Arch path Anat. 1925;256:629–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Florey H. General Pathology based on Lectures delivered at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford. Chapter 40. Philiadelphia and London: W.B Saunders; 1958. Tuberculosis; pp. 829–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornil V, Ranvier L. A manual of pathological histology translated with notes and additions by EO Shakespeare and JHC Simms. Part III, Section I Chapter II. Philadephia: Henry C Lea; 1880. Pathological histology of the respiratory apparatus; pp. 394–445. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Im JG, Itoh H, Shim YS, Lee JH, Ahn J, Han MC, Noma S. Pulmonary tuberculosis: CT findings--early active disease and sequential change with antituberculous therapy. Radiology. 1993;186:653–60. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.3.8430169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fish R, Pagel W. The morbid anatomy of epituberculosis. J Path Bact. 1938;47:593–601. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kondo S, Miyagawa T, Ito M. Reevaluation of pathogenesis of epituberculosis in infants and children with tuberculosis. Kekkaku. 2007;82:569–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welsh KJ, Risin SA, Actor JK, Hunter RL. Immunopathology of Postprimary Tuberculosis: Increased T-Regulatory Cells and DEC-205-Positive Foamy Macrophages in Cavitary Lesions. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2011;2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/307631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mays TJ. Pulmonary Consumption, Pneumonia and Allied Diseaeses of the Lungs: Their etiology, pathology and treatment with a chapter onf physical diagnosis. New York: E.B. Treat & Company; 1901. Pathology of Pulmonary Consumption; pp. 247–88. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hektoen L, Reisman D. A Text-Book of Pathology for the use of students and practitoners of medicine and surgery. London and Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders & Company; 1901. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andreu J, Caceres J, Pallisa E, Martinez-Rodriguez M. Radiological manifestations of pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur J Radiol. 2004;51:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatipoglu ON, Osma E, Manisali M, Ucan ES, Balci P, Akkoclu A, Akpinar O, Karlikaya C, Yuksel C. High resolution computed tomographic findings in pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax. 1996;51:397–402. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.4.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kashyap S, Mohapatra PR, Saini V. Endobronchial tuberculosis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2003;45:247–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins J, Blankenbaker D, Stern EJ. CT patterns of bronchiolar disease: what is “tree-in-bud”? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:365–70. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.2.9694453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sucena M, Amorim A, Machado A, Hespanhol V, Magalhaes A. Endobronchial tuberculosis -- clinical and bronchoscopic features. Rev Port Pneumol. 2004;10:383–91. doi: 10.1016/s0873-2159(04)05014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura A, Hebisawa A, Fukushima K, Yotsumoto H, Mori M. Lipoid pneumonia in lung cancer: radiographic and pathological features. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:492–6. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.8.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soni R, Barnes D, Torzillo P. Post obstructive pneumonia secondary to endobronchial tuberculosis--an institutional review. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29:841–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Plessinger VA, Jolly PN. Rasmussen’s aneurysms and fatal hemorrhage in pulmonary tuberculosis. Am Rev Tuberc. 1949;60:589–603. doi: 10.1164/art.1949.60.5.589. illust. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grosset J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the extracellular compartment: an underestimated adversary. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:833–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.833-836.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anders JM. A text-book of the practice of medicine - illustrated. 5. Philadelphia and London: W.B Saunders & Company; 1902. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corbett EL, Zezai A, Cheung YB, Bandason T, Dauya E, Munyati SS, Butterworth AE, Rusikaniko S, Churchyard GJ, Mungofa S, Hayes RJ, Mason PR. Provider-initiated symptom screening for tuberculosis in Zimbabwe: diagnostic value and the effect of HIV status. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:13–21. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.055467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaplan G, Post FA, Moreira AL, Wainwright H, Kreiswirth BN, Tanverdi M, Mathema B, Ramaswamy SV, Walther G, Steyn LM, Barry CE, 3rd, Bekker LG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth at the cavity surface: a microenvironment with failed immunity. Infect Immun. 2003;71:7099–108. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7099-7108.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hunter RL, Venkataprasad N, Olsen MR. The role of trehalose dimycolate (cord factor) on morphology of virulent M. tuberculosis in vitro. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ewart W. The Gulstonian lectures on pulmonary cavities: Their origin, growth and repair. British Medical Journal. 1882 March 11–April 15;:333–7. 415–8, 53–56. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.1106.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rook GA, Dheda K, Zumla A. Immune responses to tuberculosis in developing countries: implications for new vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:661–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barry CE, 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V, Dick T, Ehrt S, Flynn J, Schnappinger D, Wilkinson RJ, Young D. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:845–55. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aaron L, Saadoun D, Calatroni I, Launay O, Memain N, Vincent V, Marchal G, Dupont B, Bouchaud O, Valeyre D, Lortholary O. Tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients: a comprehensive review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:388–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee KM, Choe KH, Kim SJ. Clinical investigation of cavitary tuberculosis and tuberculous pneumonia. Korean J Intern Med. 2006;21:230–5. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2006.21.4.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liebana E, Johnson L, Gough J, Durr P, Jahans K, Clifton-Hadley R, Spencer Y, Hewinson RG, Downs SH. Pathology of naturally occurring bovine tuberculosis in England and Wales. Vet J. 2008;176:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Creighton C. Bovine Tubercuosis in Man: An account of the Pathology of Suspected Cases. London: MacMillan and Co; 1881. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Francis J. Bovine Tuberculosis. Including a corntast with human tuberculosis. New York: Staples Press limited; 1947. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stamp JT. Bovine pulmonary tuberculosis. J Comp Pathol. 1948;58:9–23. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(48)80002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Medlar E. Pulmonary tuberculosis in cattle. The location and type of lesion in naturllly acquired tuberulosis. Am Rev of Tuberculosis. 1940;41:283–303. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gortazar C, Vicente J, Gavier-Widen D. Pathology of bovine tuberculosis in the European wild boar (Sus scrofa) Vet Rec. 2003;152:779–80. doi: 10.1136/vr.152.25.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu G, Ji S. Analysis of lobar pneumonic tuberculosis. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 1998;21:85–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bandera A, Gori A, Catozzi L, Degli Esposti A, Marchetti G, Molteni C, Ferrario G, Codecasa L, Penati V, Matteelli A, Franzetti F. Molecular epidemiology study of exogenous reinfection in an area with a low incidence of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2213–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2213-2218.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hutchison JH. The pathogenesis of epituberculosis in children with a note on obstructive emphysema. Glasgow Med J. 1949;30:271–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Korf J, Stoltz A, Verschoor J, De Baetselier P, Grooten J. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall component mycolic acid elicits pathogen-associated host innate immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:890–900. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hunter RL, Olsen MR, Jagannath C, Actor JK. Multiple roles of cord factor in the pathogenesis of primary, secondary, and cavitary tuberculosis, including a revised description of the pathology of secondary disease. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:371–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guidry TV, Hunter RL, Jr, Actor JK. Mycobacterial glycolipid trehalose 6,6′-dimycolate-induced hypersensitive granulomas: contribution of CD4+ lymphocytes. Microbiology. 2007;153:3360–9. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/010850-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geisel RE, Sakamoto K, Russell DG, Rhoades ER. In Vivo Activity of Released Cell Wall Lipids of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Is Due Principally to Trehalose Mycolates. J Immunol. 2005;174:5007–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ulrichs T, Lefmann M, Reich M, Morawietz L, Roth A, Brinkmann V, Kosmiadi GA, Seiler P, Aichele P, Hahn H, Krenn V, Gobel UB, Kaufmann SH. Modified immunohistological staining allows detection of Ziehl-Neelsen-negative Mycobacterium tuberculosis organisms and their precise localization in human tissue. J Pathol. 2005;205:633–40. doi: 10.1002/path.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mogga SJ, Mustafa T, Sviland L, Nilsen R. In situ expression of CD40, CD40L (CD154), IL-12, TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma and TGF-beta1 in murine lungs during slowly progressive primary tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 2003;58:327–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Converse PJ, Dannenberg AM, Jr, Estep JE, Sugisaki K, Abe Y, Schofield BH, Pitt ML. Cavitary tuberculosis produced in rabbits by aerosolized virulent tubercle bacilli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4776–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4776-4787.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dubos R. Properties and structures of tubercle bacilli concerned in their pathogenicity. Symposia of the Society for General Microbiology. 1955;5:103–25. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rana FS, Hawken MP, Mwachari C, Bhatt SM, Abdullah F, Ng’ang’a LW, Power C, Githui WA, Porter JD, Lucas SB. Autopsy study of HIV-1-positive and HIV-1-negative adult medical patients in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:23–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200005010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]