Abstract

Background

We aimed to investigate whether employment status was associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a population of morbidly obese subjects.

Methods

A total of 143 treatment-seeking morbidly obese patients completed the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Obesity and Weight-Loss Quality of Life (OWLQOL) questionnaires. The former (SF-36) is a generic measure of physical and mental health status and the latter (OWLQOL) an obesity-specific measure of emotional status. Multiple linear regression analyses included various measures of the HRQoL as dependent variables and employment status, education, marital status, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and treatment choice as independent variables.

Results

The patients (74% women, 56% employed) had a mean (SD, range) age of 44 (11, 19–66) years and a mean BMI of 44.3 (5.4) kg/m2. The employed patients reported significantly higher HRQoL scores within all eight subscales of SF-36, while the OWLQOL scores were comparable between the two groups. Multiple linear regression confirmed that employment was a strong independent predictor of HRQoL according to the SF-36. Based on part correlation coefficients, employment explained 16% of the variation in the physical and 9% in the mental component summaries of SF-36, while gender explained 22% of the variation in the OWLQOL scores.

Conclusion

Employment is associated with the physical and mental HRQoL of morbidly obese subjects, but is not associated with the emotional aspects of quality of life.

Keywords: Employment, Obesity, Health-related quality of life

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) refers to the impact of a medical condition on the physical, social, and emotional functioning reported by a respondent. HRQoL is often assessed by standardized questionnaires, the generic SF-36 being the most commonly used [1]. Several lines of evidence indicate that there is a relationship between increasing levels of obesity and impaired HRQoL [2, 3], the latter of which has been shown to improve after bariatric surgery [4, 5].

A number of studies have addressed the relationship between socioeconomic factors and the impaired HRQoL of obese persons, with at least three finding significant associations between marital status, income, education, and the HRQoL [6–8]. There is also some evidence to suggest that obesity-related comorbidities and conditions such as hypertension and type 2 diabetes may influence HRQoL in morbidly obese women and men [3, 7, 8]. However, previous studies have taken into account only a limited number of comorbidities and have done so with variable diagnostic precision. Some of these studies are devoid of socioeconomic considerations in their analyses.

Morbidly obese women have been found to have lower HRQoL than men, particularly in terms of the impairment of physical function and body image/body satisfaction [9–11]. In addition, white subjects would seem to have lower quality of life than other ethnic groups [10, 11]. Finally, morbidly obese patients seeking surgery have been shown to have lower HRQoL than those who do not [12].

A study of 51 morbidly obese subjects treated with duodenal switch [6] demonstrated a statistically significant association between employment and the physical and mental component scores of the SF-36. The study was, however, limited by lack of adjustments for obesity-related comorbidities and conditions which might have influenced HRQoL. In addition, no obesity-specific measure of quality of life was addressed.

We aimed to investigate whether the general and obesity-specific HRQoL of treatment-seeking morbidly obese Caucasian subjects were associated with employment status after adjustments for confounding factors.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The non-randomized controlled MOBIL study (Morbid Obesity treatment, Bariatric surgery versus Intense Lifestyle intervention, Clinical Trials.gov number NCT00273104) was designed to compare the effects of bariatric surgery and intensive lifestyle intervention on various comorbidities, eating behavior, and quality of life [13]. In the present cross-sectional study, 145 patients were asked to complete two questionnaires related to HRQoL at baseline. Two patients did not complete the questionnaires, and as such, data from 143 morbidly obese subjects, all but one Caucasian, was included in the analysis.

The regional Ethics Committee for Medical Research approved the study protocol, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave informed written consent before enrolment. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research.

Outcomes, Explanatory Variables, and Potential Confounders

The main outcome was HRQoL as measured by various questionnaires exploring the physical, mental, and emotional aspects. The main explanatory variable was employment status, with possible confounders adjusted for including socioeconomic factors, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), obesity-related comorbidities, and treatment-seeking status. Persons receiving income from either full-time or part-time work were defined as employed.

HRQoL

Two different questionnaires were used to measure HRQoL: the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Obesity and Weight-Loss Quality of Life (OWLQOL). SF-36 is a commonly used generic measure of health status based on a comprehensive set of items. It has eight subscales (physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, role emotional, social function, vitality, and mental health), which generate two general health summaries: the physical and mental component scores [14, 15]. The OWLQOL primarily measures the emotions and feelings which result from being obese and trying to lose weight. The instrument consists of 17 statements about weight and quality of life. All items are rated on a seven-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a lot), with lower scores better than higher. The OWLQOL scale is adjusted to 0–100 (higher = better) after reversing the scores. The OWLQOL was originally produced at the University of Washington and has been further developed through input from five European countries and the USA. The questions have been translated into Norwegian and are available with permission from the Seattle Quality of Life Group, University of Washington [16, 17].

Clinical Examination

All participants underwent a medical examination by a physician during their first consultation. Demographic data, socioeconomic history, and medical history were recorded using standardized schemes. Weight and height were measured with patients wearing light clothing and no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Blood pressure was measured three times after at least 5 min rest, at the right or left brachial artery, with the patient in a sitting position. The average of the second and third measurements was registered. Hypertension was confirmed if either systolic blood pressure was greater than 140 mmHg, if diastolic blood pressure was greater than 90 mmHg, or if the patient received antihypertensive drugs.

All patients underwent one overnight sleep with a portable monitor, the Embletta™ system; which has both high sensitivity and specificity when compared to the “gold standard” overnight polysomnography used to identify obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients [18]. OSA was diagnosed in patients having moderate to severe sleep apnea (apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 15 events per hour) as these patients are more likely to have symptoms than those with mild OSA.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed in patients either treated with glucose-lowering drugs or with a fasting serum glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or a 2-h glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l after the ingestion of a 75-g anhydrous glucose solution [13].

In addition, all patients completed a questionnaire on their diet and physical activity [19]. Patients were categorized as having a sedentary lifestyle if they had no (less than 10 min a week) aerobic moderate or vigorous activity based on their answer to the following question: “Do you perform any physical activity and exercise making you a little short of breath (more than 10 min a week bicycling, swimming, walking, skiing, dancing, or golfing)?”

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean (SD) or n (percent) unless otherwise stated. The reliability of the HRQoL scales was assessed with inter-item analysis using Chronbach's alpha. The scales were examined for normality using skewness tests and Kolmogorov–Smirnov testing. None of the scales had significant departures from normality. The continuous independent variables underwent the same normality testing and neither was found to have significant departures from normality.

Between group comparisons were analyzed using independent samples t test and χ 2. The correlation between each of the independent and the dependent variables was calculated using Pearson correlation coefficient. We also performed three multiple linear regression analyses, one for each scale as the dependent variable. Ten predefined explanatory variables were included in each model. In examining the variation of inflation factors in the models, we found no consequential multicollinearity between the independent variables. The probability–probability plot between expected and observed cumulative distribution was considered acceptable. Semi-partial (part) correlation coefficients were squared in order to calculate the percentage of total variance in the dependent variable explained by a given independent variable. Throughout, we report two-tailed P values, as we considered values below .05 to be statistically significant. Particular attention should, however, be directed towards small P values, e.g., those below .01, because a considerable number of P values have been calculated. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS v.17.0.

Results

The reliability of the scales as measured by the Chronbach's alpha was 0.93 for the SF-36 and 0.95 for the OWLQOL. Table 1 shows demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics according to employment status. The 143 morbidly obese patients (74% women) had a mean (SD, range) age of 44 (11, 19–66) years and a mean BMI of 44.3 (5.4) kg/m2. The employment rate was 56%. The employed and unemployed groups were comparable with respect to age, gender, BMI, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity-related comorbidities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics among 143 morbidly obese subjects according to employment

| Variable | Total | Employed (n = 80) | Unemployed (n = 63) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.6 (10.7) | 44.1 (10.2) | 45.2 (11.3) | 0.557 |

| Women | 106 (74%) | 63 (79%) | 43 (68%) | 0.180 |

| Start obesity | ||||

| <12 years | 34 (25%) | 22 (28%) | 12 (20%) | |

| 12–20 years | 32 (23%) | 14 (18%) | 18 (30%) | |

| >20 years | 72 (52%) | 42 (54%) | 30 (50%) | 0.207 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 44.3 (5.4) | 43.7 (5.6) | 45.0 (5.2) | 0.180 |

| Current smoker (yes) | 38 (27%) | 19 (24%) | 19 (31%) | 0.445 |

| Sedentary lifestyle (yes) | 36 (31%) | 21 (33%) | 15 (28%) | 0.689 |

| Socioeconomic factors | ||||

| Married/cohabitant (yes) | 89 (62%) | 54 (68%) | 35 (56%) | 0.166 |

| Length of education | ||||

| Basic (<9 years) | 35 (25%) | 9 (11%) | 26 (42%) | |

| Intermediate (9–12 years) | 72 (51%) | 49 (61%) | 23 (38%) | |

| Higher (>12 years) | 34 (24%) | 22 (28%) | 12 (20%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension (yes) | 52 (36%) | 28 (35%) | 24 (38%) | 0.729 |

| Type 2 diabetes (yes) | 44 (31%) | 24 (30%) | 20 (32%) | 0.855 |

| OSA (AHI ≥15; yes) | 43 (31%) | 21 (27%) | 22 (37%) | 0.267 |

| Seeking surgery (yes) | 84 (59%) | 41 (51%) | 43 (68%) | 0.059 |

| Quality of life | ||||

| SF-36 physical | 46 (24) | 55 (22) | 33 (20) | <0.001 |

| SF-36 mental | 55 (25) | 62 (23) | 47 (24) | 0.001 |

| OWLQOL emotional | 35 (24) | 35 (23) | 35 (25) | 0.864 |

Data are given as mean (SD) or number (percent). P values were calculated using independent samples t test or χ 2

Nearly all of the unemployed patients (91%) received benefits from the state, including disability benefits (38%), rehabilitation benefits (24%), sick leave (16%), unemployment benefits (5%), retirement pensions (5%), and unknown (3%). The unemployed group had a significantly lower average level of education and tended to opt for bariatric surgery more often than their employed counterparts (Table 1).

The physical and mental scores of SF-36 were significantly higher in the employed group than the unemployed group (Table 1). The emotional aspects of quality of life as measured with the OWLQOL did not differ between the two groups (P = .86).

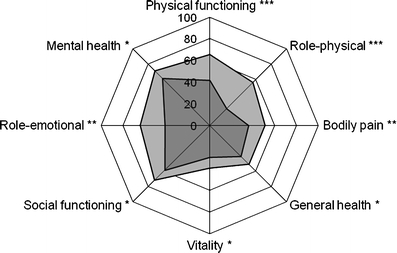

Differences between the employed and the unemployed groups within the various subscales of SF-36 are shown in Fig. 1. The employed patients reported significantly higher HRQoL within all eight subscales; this was most pronounced within the physical function, role physical, bodily pain, and role emotional subscales.

Fig. 1.

The SF-36 subscale mean scores among employed and unemployed patients. The SF-36 subscales differed significantly between employed (light grey) and unemployed (dark grey) patients. Independent samples t test; *** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The multiple linear regression models (Table 2) confirmed that employment was significantly associated with higher scores for general physical and mental health according to both SF-36 dimensions after adjustment for confounding factors. In contrast, only gender was significantly associated with the emotional aspects of obesity as measured by the OWLQOL (women had lower scores than men). Neither age, level of obesity, comorbidities, nor education were significantly associated with HRQoL.

Table 2.

Predictors of HRQoL in 144 morbidly obese patients

| QOL dimension | Physical, R 2 = 0.36, beta | Mental, R 2 = 0.17, beta | Emotional, R 2 = 0.26, beta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.51*** |

| Age | −0.22* | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| BMI | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.15 |

| Marital status | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Education | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| Employment | 0.43*** | 0.33** | 0.07 |

| Hypertension | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| OSA | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Type 2 diabetes | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| Seeking surgery | 0.26** | 0.12 | 0.13 |

The main explanatory variable was employment status, with possible confounders adjusted for including other socioeconomic factors, age, gender, BMI, obesity-related comorbidities, and treatment-seeking status. Standardized beta values are given

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (linear regression)

Squared part correlations showed that employment explained 16% of the variation in the physical component score of the SF-36 and 9% of the variation in the mental component score of the SF-36. Gender explained 22% of the variation in the OWLQOL scores.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that in morbidly obese patients allocated to either surgical treatment or lifestyle intervention, employment was independently associated with both the physical and mental aspects of HRQoL. Conversely, employment was not associated with the emotional aspects of quality of life.

Employment

Our study confirms the findings of previous studies which demonstrated a relationship between participation in paid work and general HRQoL in patients undergoing bariatric surgery [6, 20]. Through our study, we are able to both extend this association to a sample of morbidly obese subjects offered either conservative or surgical treatment and to suggest that it is valid independent of confounding factors. However, we found no association between the emotional aspects of quality of life and employment status.

Our findings are also in accordance with a previous study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, which showed that employment was associated with HRQoL as measured by SF-36 [21]. It could be argued that employed patients use their physical and mental capacities and might therefore pay less attention to any general health limitations and discomfort they may have. Employment might give both a sense of inclusion and belonging, providing patients with access to both working and social networks. This hypothesis is supported by studies of both cancer patients and older adults which have shown positive associations between social networks, support, and HRQoL [22, 23]. Employment may also positively contribute to a person's self-esteem. Nevertheless, in the present study, emotional QoL was comparable among both employed and unemployed patients, indicating that participation in paid work does not seem to relieve the emotional distress of being morbidly obese [24].

The employment rate among the patients was 56%, while the overall Norwegian employment rate at the same time of the study was 73% [25]. A large proportion of the jobs patients held were within low wage service sectors like transport, accommodation, and food and health (data not shown). The Norwegian welfare system provides a significant range of benefits for persons without work. We therefore believe that poverty plays a minor role in explaining why unemployed morbidly obese patients reported impaired HRQoL.

Gender

The general physical and mental HRQoL scores were nearly equal between the morbidly obese men and women in the study. However, the obesity-specific emotional measurement OWLQOL showed that women reported significantly more concerns about emotional and social distress. Previous studies have demonstrated impaired HRQoL among morbidly obese women [9, 10]. Some authors have also suggested there to be less social obesity stigmatization among African American women [11]. Our study confirms that for white females, obesity has a stronger effect upon the emotional quality of life than the general HRQoL. The question whether this finding is also valid for women of other ethnicities should be addressed in future studies.

Comorbidities

We found no statistically significant associations between weight-related comorbidities and quality of life. This finding concurs with at least one previous study [3]. Most patients had either no symptoms or only mild symptoms as a result of the comorbidities and did not seem to be very bothered by these. Many of them were not even aware of their comorbidity before the study examination. Thus, it seemed that being unemployed overshadowed the potential problems following hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and type 2 diabetes.

Treatment-Seeking Status

In accordance with previous studies [11, 12, 26], patients seeking surgery reported significantly lower physical health according to the SF-36. However, patients in many of these studies did not have any appropriate alternative to surgery. In the MOBIL study, by contrast, patients had two different obesity treatment choices: bariatric surgery or an intensive (partly residential) lifestyle program.

Limitations

Our cross-sectional study has limitations. Firstly, the finding of a positive association between work status and HRQoL does not infer any causal relationship. As such, there is a need for further exploration through longitudinal studies. Secondly, the “healthy worker effect,” a phenomenon of any group of workers likely to be more healthy than the population as a whole, can give rise to both selection and confounding bias [27]. Occupational groups of patients often have fewer illnesses and disabilities and as such are more likely to be healthy than the patient population as a whole. Thirdly, it may be hypothesized that various levels of disability partly explain both poor HRQoL and unemployment. Unfortunately, since the precise level of disability was not assessed in the present study, we could not test this hypothesis. Finally, our results may not be valid in non-white populations.

Conclusions

In summary, our study of predominantly white morbidly obese subjects has shown that being employed was significantly associated with better general physical and mental HRQoL and that female gender was significantly associated with the negative emotional results of obesity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Berit Mossing Bjørkås for assisting with sampling and logistics, Line Kristin Johnson for collecting dietary and activity data, and Matthew McGee for proofreading the manuscript. The study was supported financially by educational grants from Novo Nordisk A/S (to DH), Vestfold Hospital Trust (to DH and RSL), and Evjeklinikken A/S (to TIK).

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Garratt A, Schmidt L, Mackintosh A, et al. Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ. 2002;324:1417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia H, Lubetkin EI. The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:156–164. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sach TH, Barton GR, Doherty M, et al. The relationship between body mass index and health-related quality of life: comparing the EQ-5D, EuroQol VAS and SF-6D. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:189–196. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, et al. Treatment of mild to moderate obesity with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or an intensive medical program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:625–633. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choban PS, Onyejekwe J, Burge JC, et al. A health status assessment of the impact of weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:491–497. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen JR, Aasprang A, Bergsholm P, et al. Anxiety and depression in association with morbid obesity: changes with improved physical health after duodenal switch. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rejeski WJ, Lang W, Neiberg RH, et al. Correlates of health-related quality of life in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:870–883. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sendi P, Brunotte R, Potoczna N, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with class II and class III obesity. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1070–1076. doi: 10.1381/0960892054621323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duval K, Marceau P, Lescelleur O, et al. Health-related quality of life in morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:574–579. doi: 10.1381/096089206776944968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res. 2002;10:748–756. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White MA, O’Neil PM, Kolotkin RL, et al. Gender, race, and obesity-related quality of life at extreme levels of obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12:949–955. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Nunen AM, Wouters EJ, Vingerhoets AJ, et al. The health-related quality of life of obese persons seeking or not seeking surgical or non-surgical treatment: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1357–1366. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9241-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hofso D, Ueland T, Hager H, et al. Inflammatory mediators in morbidly obese subjects; associations with glucose abnormalities and changes after oral glucose. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:451–458. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Kosinski M. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a manual for users of version 1. 2. Lincoln: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niero M, Martin M, Finger T, et al. A new approach to multicultural item generation in the development of two obesity-specific measures: the obesity and weight loss quality of life (OWLQOL) questionnaire and the weight-related symptom measure (WRSM) Clin Ther. 2002;24:690–700. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(02)85144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, Rothman M. Performance of two self-report measures for evaluating obesity and weight loss. Obes Res. 2004;12:48–57. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingli K, Coleman EL, Vennelle M, et al. Evaluation of a portable device for diagnosing the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:253–259. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00298103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen LF, Solvoll K, Johansson LR, et al. Evaluation of a food frequency questionnaire with weighed records, fatty acids, and alpha-tocopherol in adipose tissue and serum. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:75–87. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y, Hesser JE. Associations between health-related quality of life and demographics and health risks. Results from Rhode Island's 2002 behavioral risk factor survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:14. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Henriksen M, et al. Relationship between sick leave, unemployment, disability, and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:402–412. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218762.61217.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Social support and health-related quality of life among older adults—Missouri, 2000. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;2005:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sultan S, Fisher DA, Voils CI, et al. Impact of functional support on health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA. Psychological functioning of obese individuals. Diabetes Spectr. 2003;16:245–252. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.16.4.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistics Norway. Workforce, Norway, Population aged 15–74 by labour force status (LFS) and sex. Per cent. http://www.ssb.no/english/subjects/06/01/aku_en/tab-2010-08-05-02-en.html. Access date: 9 Feb 2010.

- 26.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Pendleton R, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients seeking gastric bypass surgery vs non-treatment-seeking controls. Obes Surg. 2003;13:371–377. doi: 10.1381/096089203765887688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steenland K, Pinkerton LE. Mortality patterns following downsizing at pan american world airways. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]