Abstract

Previously, we described the isolation of the Plasmodium yoelii sequence-related molecules P. yoelii MSP-7 (merozoite surface protein 7) and P. yoelii MSRP-2 (MSP-7-related protein 2) by their ability to interact with the amino-terminal end of P. yoelii MSP-1 in a yeast two-hybrid system. One of these molecules was the homologue of Plasmodium falciparum MSP-7, which was biochemically isolated as part of the shed MSP-1 complex. In the present study, with antibodies directed against recombinant proteins, immunoprecipitation analyses of the rodent system demonstrated that both P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 could be isolated from parasite lysates and from parasite culture supernatants. Immunofluorescence studies colocalized P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 with the amino-terminal portion of MSP-1 and with each other on the surface of schizonts. Immunization with P. yoelii MSRP-2 but not P. yoelii MSP-7 protected mice against a lethal infection with P. yoelii strain 17XL. These results establish that both P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 are expressed on the surface of merozoites and released from the parasite and that P. yoelii MSRP-2 may be the target of a protective immune response.

Recently, many new protein molecules have been discovered on the surface of the malaria parasite, most belonging to the merozoite surface protein (MSP) family. Due to their surface exposure, they are accessible to antibodies and are therefore considered possible vaccine candidates (15, 23). Many of these surface proteins have been found to contain one or more epidermal growth factor-like domains, including MSPs 1, 4, 5, 8, and 10 (2, 3, 14, 28), some are soluble (MSP-3 and MSP-9) (24), and others have been identified as part of the shed MSP-1 complex (MSPs 6 and 7) (25, 27).

MSP-1 has been the most extensively characterized and examined for its potential biological function and possible role as a vaccine candidate. The protein is evenly distributed on the surface of the merozoite and undergoes a two-step proteolytic processing by a conserved membrane-associated protease (4, 5). MSP-1 is processed late in schizogony into 83-kDa, 30-kDa, 38-kDa, and 42-kDa fragments, which remain noncovalently associated on the surface of the parasite (14, 19, 21). The 42-kDa region at the carboxy terminus of the protein then undergoes a second proteolytic processing event into 33-kDa and 19-kDa fragments at the time of merozoite invasion. The 19-kDa region of the protein contains two epidermal growth factor-like domains and remains on the surface of the parasite through a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol anchor (6, 14). Immunization with the 19-kDa region of MSP-1 protects against lethal parasite challenge in mice and monkeys (8, 9, 10, 12, 16).

Recently, MSP-6 and MSP-7 have been found to be associated with the shed MSP-1 complex in Plasmodium falciparum (25, 27). MSP-7 is a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 22 kDa, expressed in late-stage parasites; the gene encoding this protein is on chromosome 13 and is part of a multigene family (22, 25). Previously, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to identify proteins that interact with the amino-terminal portion of Plasmodium yoelii MSP-1 and identified two sequence-related molecules, one of which is the homologue to MSP-7 originally described in P. falciparum (22, 25). Through BLAST analysis, we have identified six genes in P. falciparum that are the homologues to the P. yoelii genes isolated in the yeast two-hybrid screen and presented the molecular characterization of MSP-related proteins (MSRPs) 1, 2, and 3 in P. falciparum. In this study, we have undertaken the characterization of the P. yoelii homologues of MSP-7 and MSRP-2. We used the animal model to test the potential of these proteins to protect mice against lethal parasite challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

A 1,296-bp fragment corresponding to amino acids 82 to 514 of P. yoelii MSP-183a (18) was amplified from P. yoelii 17XL genomic DNA with primers containing EcoRI sites. The resulting fragment was cloned into the Escherichia coli expression vector pGEX4T-1 (Pharmacia Biotech), creating an in-frame fusion with glutathione S-transferase (GST). To express P. yoelii MSP-7 in E. coli, clone 6 from the library screen was digested with EcoRI and XhoI, and the resulting fragment of 828 bp (amino acids 47 to 324) was cloned in the poly(His) tag vector pET-28a (Novagen) for expression (22). Primers were designed to amplify a portion of library clone 5, corresponding to P. yoelii MSRP-2, lacking the proline- and serine-rich extension, resulting in a fragment of 789 bp (amino acids 54 to 317). The resulting BamHI-to-XhoI fragment was cloned into the pET-28a vector for expression. All sequences lack their amino-terminal signal peptides, and all DNA sequences and junctions were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins.

The amino-terminal portion of P. yoelii MSP-183a was expressed as a fusion with GST, and P. yoelii MSP-7 and MSRP-2 were expressed as fusions with a six-histidine tag. All constructs were expressed in E. coli BL-21(DE3) Codon Plus cells (Stratagene). P. yoelii MSP-183a was purified under native conditions with glutathione agarose beads and eluted in 5.0 mM glutathione as previously described (22). P. yoelii MSP-119 was expressed and purified as previously described as a fusion with GST (9, 10). P. yoelii MSP-7 and MSRP-2 were purified with nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-agarose (Qiagen) in a batch and column fashion according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity and integrity of the proteins were assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized with Coomassie blue. Protein concentrations were determined by a Bradford assay (protein reagent; Bio-Rad).

Serum.

Male BALB/cByJ mice 6 to 8 weeks old were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and housed in our Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-approved animal facility. For the production of polyclonal antisera, mice received three subcutaneous injections 3 weeks apart of 100 μg of recombinant protein (P. yoelii MSP-183a, P. yoelii MSP-7, or P. yoelii MSRP-2) with the Ribi adjuvant system (Corixa). Normal mouse serum was obtained from nonimmunized animals, and serum was obtained 2 weeks following the third immunization from the experimental groups.

Rabbit antisera against all three of the recombinant proteins was commercially prepared (Lampire Biological Laboratories, Pipersville, Pa.). The animals received three subcutaneous injections of 300 μg of recombinant protein with complete Freund's adjuvant for the first injection and incomplete Freund's adjuvant for the subsequent injections. The first and second immunizations were 3 weeks apart, and the second and third immunizations were 2 weeks apart. Serum was obtained 2 weeks following the final boost. Preimmune serum was obtained and screened prior to the immunizations.

Immunizations.

Groups of four to eight male BALB/cByJ mice were immunized with 25 μg of the recombinant His fusions or 50 μg of the GST fusion proteins. In two challenge trials, the animals received three subcutaneous injections (of 25 μg or 50 μg each) of the recombinant protein with Ribi (Corixa) adjuvant 3 weeks apart. In the third challenge trial, the animals received three subcutaneous injections of recombinant protein with complete Freund's adjuvant for the first immunization and incomplete Freund's adjuvant for the two boosting immunizations 3 weeks apart. All groups were challenged intravenously 2 weeks following the last boost with 104 parasitized erythrocytes. Control animals were immunized with their respective adjuvant in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

Parasites and experimental infections.

P. yoelii 17XL was maintained as a cryopreserved stabilate. Blood stage infections were initiated by intraperitoneal injection of parasitized erythrocytes into a donor animal, and infections were monitored on a daily basis by thin tail blood smears and Giemsa staining between days 5 and 25 postinfection. An average of 300 cells were counted per slide. Animals were removed from the study when their parasitemia exceeded 50% or they were obviously moribund.

Indirect immunofluorescence.

Parasitized blood was collected from mice infected with P. yoelii 17XL when the parasitemia was 20 to 25%. Parasitized cells were washed once and separated on a Percoll gradient to collect the late stages. Cells were washed once in PBS, pelleted, and resuspended in equal volumes of PBS. Thin blood smears were prepared, air dried, and fixed in methanol-acetone (1:1) for 20 min at −20°C. Slides were air dried and stored at −20°C until used. Slides were hydrated for 5 min at room temperature in PBS. Fixed cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber with normal mouse serum, immune mouse serum, preimmune rabbit serum, or immune rabbit serum at a 1:100 dilution in PBS. Slides were washed three times in PBS for 5 min with agitation. The slides were then incubated as described above with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma) with 10% normal goat serum (Gibco) diluted 1:100 in PBS and rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) diluted 1:100 in PBS. Combination slides with P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-183a or P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSP-183a were incubated separately with their primary and secondary antibodies, while the combination slides with P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 were incubated simultaneously with their primary antiserum and separately with their secondary antibodies. Slides were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 15 min at 37°C with Hoechst cell stain at a 1:1,000 dilution. Slides were washed three times for 5 min with PBS, mounted with an antifade solution (Molecular Probes), sealed, and visualized.

Antibody assay.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed to measure prechallenge antibody responses. Serum samples were collected from the tail vein 2 to 3 days prior to parasite challenge; each well of a 96-well flat-bottomed plate was coated with 50.0 ng of recombinant protein in 0.1 M sodium carbonate, pH 9.6, overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed three times with PBS and 0.1% Tween 20. Prechallenge serum was serially diluted and assayed. The serum was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then washed three times with 1× PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. A goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was incubated for 30 min at room temperature at a dilution of 1:2,000. The plate was then washed four times with PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. The plate was developed at room temperature with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (Promega). Color development was stopped with 1 M HCl and read at an optical density of 450 nm. ELISA reactions from adjuvant-only controls were performed and subtracted as background from each assay.

Radiolabeling and immunoprecipitations.

Labeling of P. yoelii-parasitized erythrocytes was done in a 1-ml volume in a 24-well plate; 200 μl of parasitized erythrocytes was added to 800 μl of modified minimal essential medium without methionine and cysteine, 50.0 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 100 to 200 μCi of [35S]methionine-cysteine (Perkin Elmer). The plate was gassed with 5% CO2 and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Labeled material was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min to pellet the cells. Culture supernatant and pellets were frozen at −80°C. The pellets were thawed and resuspended in 5 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20.0 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50.0 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM EGTA, 1% Brij 58, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and incubated on ice for 15 to 20 min. Solutions were then pelleted in the ultracentrifuge at 25,000 × g for 1 h; 25 μl of the soluble radiolabeled material and culture supernatant were used in trichloroacetic acid precipitations.

From 1 × 105 to 3 × 105 cpm of radiolabeled soluble antigen or culture supernatant was used per immunoprecipitation reaction. P. yoelii immunoprecipitations used 200 μl of soluble antigen and 150 μl of radiolabeled supernatant in their respective reactions. All samples were preabsorbed with normal mouse serum and then incubated with 1 to 5 μl of their respective antiserum for 30 min on ice. Samples were then incubated with 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) as the absorbent for 30 min on ice with mixing. Samples were than underlaid with 200 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer (20.0 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 50.0 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 1.0 M sucrose. The sample was then centrifuged for 3 min at 5,000 × g. Beads were washed three times with 200 μl of immunoprecipitation buffer and finally resuspended in 20 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer. Samples were boiled for 5 min and separated on an SDS-10% PAGE gel. The proteins were fixed for 30 min by incubating the gel with 10% acetic acid and 50% methanol at room temperature with agitation. The gel was then incubated in Amplify solution (Amersham NAMP 100) for 30 min at room temperature with agitation. Finally, the gel was dried for 1 h at 80°C and exposed to film at −80°C for 1.5 to 4 weeks.

Statistical analysis.

The Fisher exact probability test was used to determine the statistical significance in the difference in the numbers of surviving animals between the immunized and control groups. A Mann-Whitney U test determined the statistical differences between the peak parasitemias and between prechallenge antibody responses. GraphPad Instat (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used to perform the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Immunoprecipitations.

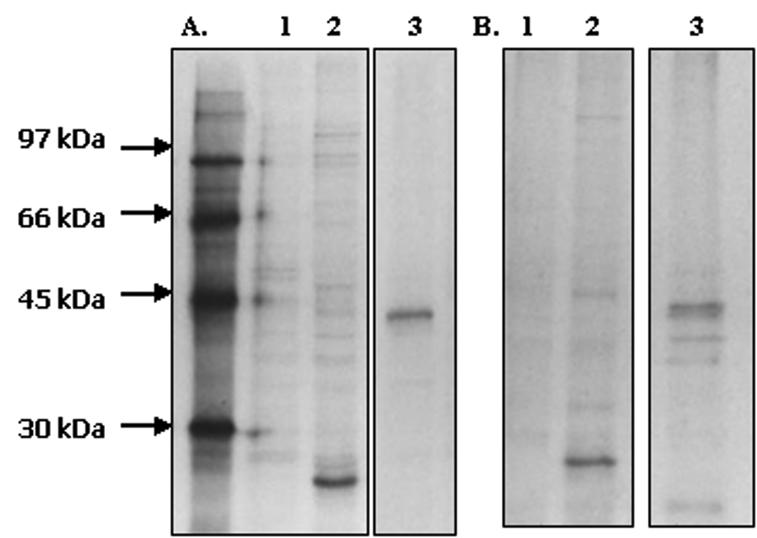

The amino-terminal portions of P. yoelii MSP-183a, P. yoelii MSRP-2, and P. yoelii MSP-7 were expressed as fusion proteins in E. coli. P. yoelii MSP-183a was expressed as a GST fusion, and P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 were expressed as His fusions. The purified proteins were used to generate specific antisera in mice and rabbits. The ability of our polyclonal antisera to detect P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 in parasite samples and culture supernatant was assessed by immunoprecipitation reactions. Holder and colleagues found that MSP-7 and MSP-6 in P. falciparum were associated with the shed MSP-1 complex (25, 27). Late-stage P. yoelii 17XL parasites were labeled in vitro with [35S]methionine-cysteine. Labeled culture supernatant and solubilized parasites were then used in immunoprecipitation reactions with polyclonal mouse serum against recombinant P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7.

The antiserum was able to precipitate P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 from both the radiolabeled culture supernatant and the soluble antigen (Fig. 1). The apparent molecular mass (approximately 26 kDa) of P. yoelii MSP-7 is slightly smaller than that of the recombinant protein, suggesting that the protein has undergone processing. Furthermore, from these studies it appears that the antisera are specific for each protein and do not cross-react. This has been confirmed by Western analysis with the purified recombinant proteins (data not shown). Normal mouse serum showed minimal reactivity with samples. These results indicate that P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 are shed into the culture supernatant, similar to the proteolytic fragments of P. falciparum MSP-1, and that the proteins can be detected in solubilized parasite material.

FIG. 1.

Immunoprecipitation with late-stage P. yoelii 17XL parasites and culture supernatants labeled in vitro for 6 h. (A) Immunoprecipitations with [35S]methionine-cysteine-labeled P. yoelii 17XL antigen. Lane 1, normal mouse serum; lane 2, mouse anti-P. yoelii MSP-7; lane 3, mouse anti-P. yoelii MSRP-2. (B) Immunoprecipitations with 35S-labeled culture supernatant. Lane 1, normal mouse serum; lane 2, mouse anti-P. yoelii MSP-7; lane 3, mouse anti-P. yoelii MSRP-2. All samples were preabsorbed with preimmune serum and exposed to film for 4 weeks.

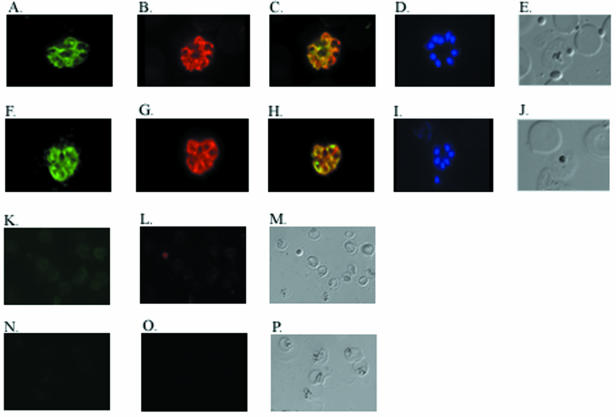

Localization of P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7.

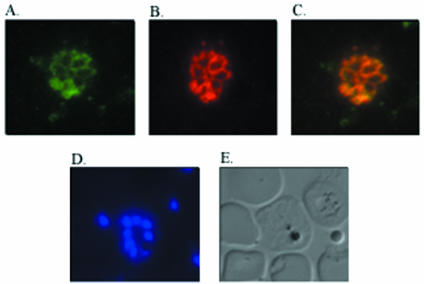

The localization of P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 was assessed with indirect immunofluorescence. P. yoelii 17XL blood stage parasites were enriched for late stages by Percoll separation and used to make thin smears that were fixed and air dried. The cell stage was assessed by counting nuclei with Hoechst cell staining (Fig. 2D and I). P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 were localized to the surface of schizonts, and this pattern is similar to that observed with the amino-terminal portion of P. yoelii MSP-1 (Fig. 2A, B, F, and G). Figure 2C shows an overlay and colocalization of P. yoelii MSRP-2 with P. yoelii MSP-183a, and Fig. 2H shows an overlay and colocalization of P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSP-183a. No fluorescent signal was detected in the normal mouse serum or the preimmune rabbit serum (Fig. 2K to P). Interestingly, combined indirect immunofluorescence also revealed that P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 are expressed on the same late-stage parasitized cell at the same time (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 are coexpressed on the surfaces of late blood stage parasites and they colocalize with the amino-terminal portion of MSP-1.

FIG. 2.

Colocalization of P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 with P. yoelii MSP-183a. Shown are immunofluorescence assay results for thin blood smears of P. yoelii 17XL parasites. The slides were incubated with reagents. (A) Rabbit anti-P. yoelii MSRP-2 and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. (B) Mouse anti-P. yoelii MSP-183a and a rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. (C) Overlay of panels A and B. (D) Hoechst cell staining. (E) Bright field of panels A to D. (F) Rabbit anti-P. yoelii MSP-7 and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. (G) Mouse anti-P. yoelii MSP-183a and a rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. (H) Overlay of panels F and G. (I) Hoechst cell staining. (J) Bright field of panels F to I. (K) Preimmune rabbit antisera and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. (L) Normal mouse antiserum and rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. (M) Bright field of panels K and L. (N) Preimmune rabbit antiserum and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. (O) Normal mouse antiserum and rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody. (P) Bright field of panels N and O.

FIG. 3.

Colocalization of P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2. Shown is immunofluorescence on thin blood smears of P. yoelii 17XL parasites. The slides were incubated with rabbit anti-P. yoelii MSP-7 followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody or (A) mouse anti-P. yoelii MSRP-2 followed by a rhodamine-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (B). (C) Overlay of panels A and B. (D) Hoechst cell staining. (E) Bright field of panels A to D.

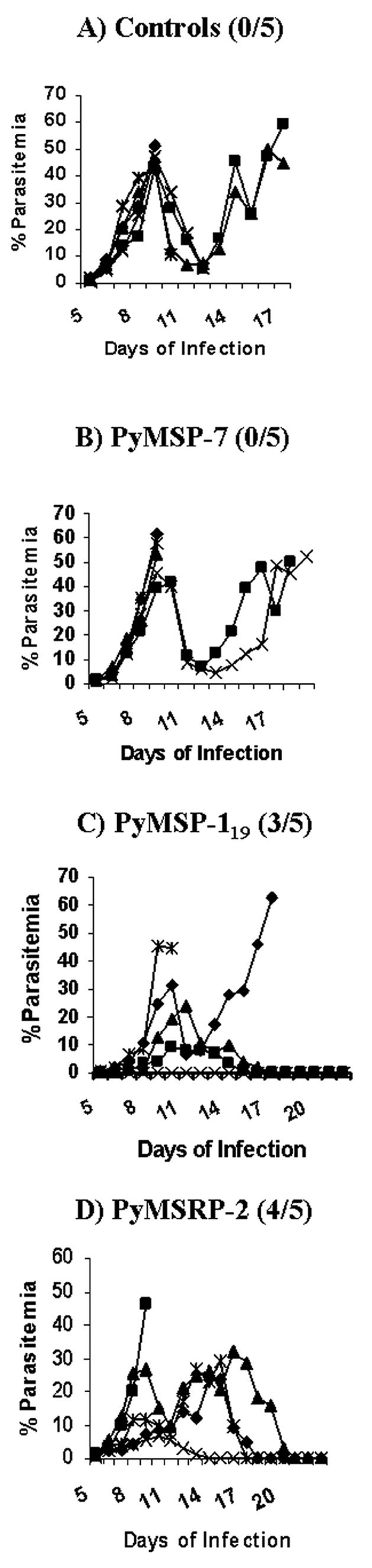

Immunization and challenge experiments.

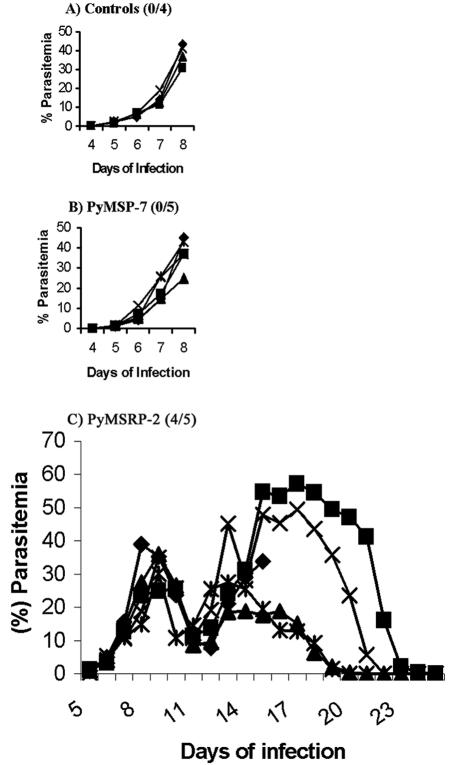

In an effort to assess the potential of P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 to protect mice against lethal parasite challenges, three challenge experiments were undertaken, immunizing groups of mice with P. yoelii MSRP-2 or P. yoelii MSP-7. In the first two trials, the proteins were administered in combination with Ribi as an adjuvant. Parasitemia was monitored on a daily basis, and the animals were removed from the study when their parasitemia exceeded 50% or they were obviously moribund. In trial 1, the mice were injected with 25.0 μg of recombinant P. yoelii MSRP-2 or P. yoelii MSP-7. Control animals were injected with Ribi in PBS, and all mice in the control group were removed from the study by day 8 postchallenge due to parasite burden. The P. yoelii MSP-7 experimental group was also removed from the study at day 8 postchallenge (Fig. 4A and B), whereas four out of five animals immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2 survived challenge (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Blood stage parasitemia in groups of mice for trial 1 with Ribi adjuvant. The number of survivors out of the total number of mice per group is shown in parentheses next to the name of the protein administered.

The P. yoelii MSRP-2 group exhibited two waves of parasitemia. Mean peak parasitemia data were analyzed on day 8 postinfection before the removal of both the control group and the P. yoelii MSP-7 experimental group. The differences in mean peak parasitemias between the groups did not reach statistical significance, but the number of surviving animals in the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group versus those of the control group and the P. yoelii MSP-7 group was statistically significant, with a P value of 0.0476 as determined by a Fisher exact probability test.

In trial 2, mice were immunized as in trial 1 with the addition of a group immunized with 60.0 μg of P. yoelii MSP-119. The number of surviving animals was similar to the results of trial 1. All five control animals and P. yoelii MSP-7 animals succumbed to infection (Fig. 5A and B). Three out of the five animals immunized with P. yoelii MSP-119 survived infection, with one animal displaying a parasitemia below 1% and then clearing the infection over the duration of the experiment (Fig. 5C), while four out of five animals immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2 survived challenge and again displayed the two waves of parasitemia seen in the first trial (Fig. 5D).

FIG. 5.

Blood stage parasitemia in groups of mice for trial 2 with Ribi adjuvant. The number of survivors out of the total number of mice per group is shown in parentheses next to the name of the protein administered.

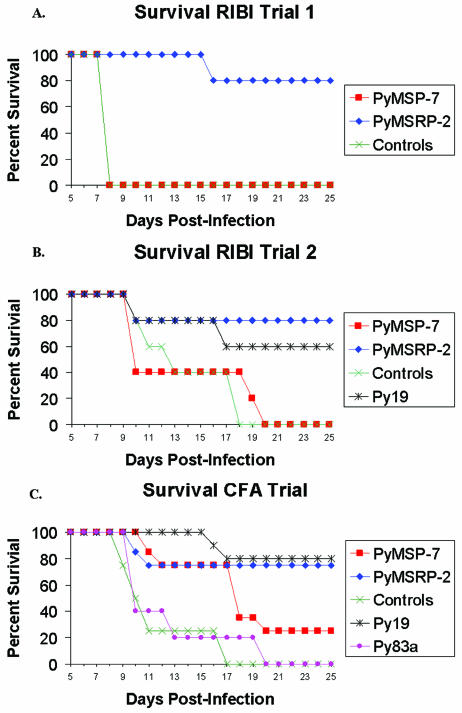

In the second trial with Ribi, the difference in mean peak parasitemia was examined on day 9 postinfection, but it was not quite statistically significant between the animals immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2 and the control animals, with a P value of 0.0556 (19.44% versus 46.66%). There was a statistically significant difference between the mean peak parasitemia of the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group and that of the P. yoelii MSP-7 experimental group, with a P value of 0.0317 (19.44% versus 51.28%). The survival rate of the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group was statistically significant compared to those of the control group and the P. yoelii MSP-7 group, with a P value of 0.0476. Overall, in the two trials with Ribi adjuvant, P. yoelii MSRP-2 protected better against lethal challenge with P. yoelii 17XL, with an 80% survival rate, compared to P. yoelii MSP-7, with a 0% survival rate (see Fig. 7A and B).

FIG. 7.

Survival curves for challenge experiments. (A) Survival curves for animals in the first trial with Ribi. (B) Trial 2 with Ribi. (C) Trial with complete Freund's adjuvant.

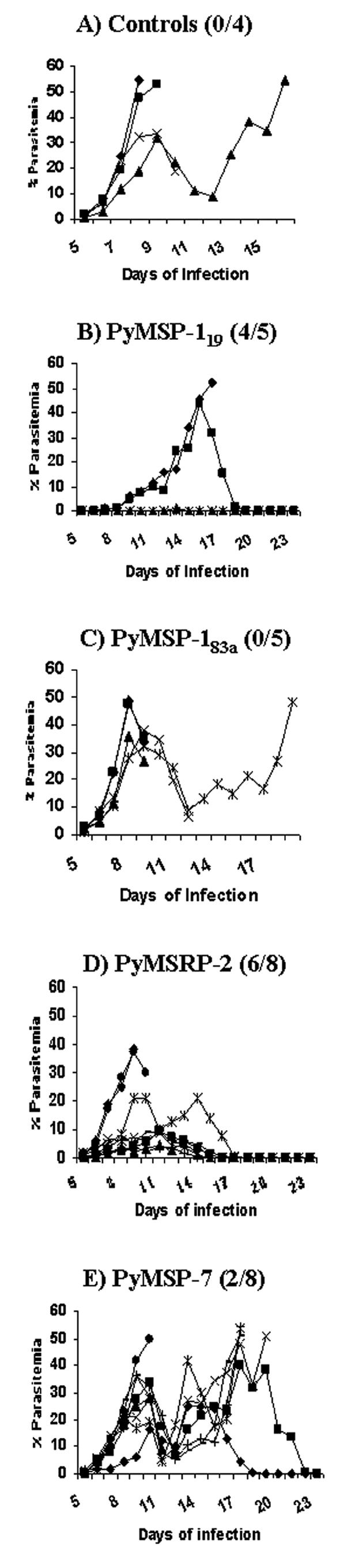

In attempts to improve protection, the animals received the same doses of recombinant proteins in combination with complete Freund's adjuvant for the first immunization and incomplete Freund's adjuvant for the boosting immunizations. The number of animals in the P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2 experimental groups was increased from five to eight. All four control mice succumbed to infection (Fig. 6A). Different regions of P. yoelii MSP-1 were also used to immunize animals to assess protective efficacy, and four out of five animals immunized with the 19-kDa region of P. yoelii MSP-1 survived challenge, while zero out of five mice immunized with the amino-terminal portion of the 83-kDa region of P. yoelii MSP-1 survived parasite challenge (Fig. 6B and C).

FIG. 6.

Blood stage parasitemia in groups of mice for trial 3 with complete Freund's adjuvant. The number of survivors out of the total number of mice per group is shown in parentheses next to the name of the protein administered.

There was a statistically significant difference in the mean peak parasitemias between the P. yoelii MSP-119 and the control animals on day 8 postinfection, with a P value of 0.0159 (0.58% versus 38.47%). In the group immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2, six out of the eight animals survived challenge while only two out of the eight animals immunized with P. yoelii MSP-7 survived challenge (Fig. 6D and E). The difference in mean peak parasitemia on day 8 postinfection reached statistical significance when the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group was compared to the control animals, with a P value of 0.0242 (11.08% versus 38.47%), but when the mean peak parasitemia of the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group was compared to that of the group immunized with P. yoelii MSP-7 on day 8 postinfection, the P value was 0.232 (11.08% versus 19.02%). There was a statistical difference in mean peak parasitemia when the P. yoelii MSRP-2-immunized group was compared with the P. yoelii MSP-183a-immunized group, with a P value of 0.01 (11.08% versus 37.94%). Five out of the eight mice in the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group exhibited parasitemia below 10%, and none of the animals exhibited the second wave of parasitemia. P. yoelii MSRP-2 gave a 75% survival rate when administered with Freund's adjuvant. This is significantly better than the 25% survival rate observed when the animals were immunized with P. yoelii MSP-7, indicating that P. yoelii MSRP-2 is better at protecting animals from lethal challenge with P. yoelii 17XL (Fig. 7C).

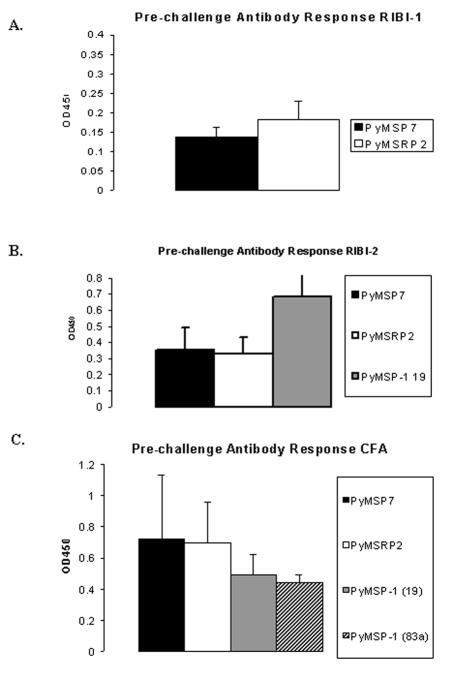

ELISA analysis on prechallenge antibody responses.

Prechallenge antibody responses were analyzed by ELISA of the antigen used in the immunizations. Small amounts of serum were collected from the tail vein 2 to 3 days prior to infection with parasites. The antigens were coated on the bottom of a 96-well flat-bottomed plate overnight at 4°C, and the serum was tested at a 1:200 dilution in replicate. Assays were developed with a horseradish peroxidase substrate and read at an absorbance of 450 nm. In trial 1 with Ribi, there was no difference in the prechallenge responses between the experimental groups. On average, the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group had an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) of 0.182, and the P. yoelii MSP-7 group had an average OD450 reading of 0.137 (Fig. 8A). In the second trial, the prechallenge antibody responses were slightly increased, with average readings of 0.33 for P. yoelii MSRP-2 and 0.35 for P. yoelii MSP-7, and the P. yoelii MSP-119 experimental group had an average prechallenge antibody response OD450 reading of 0.683 (Fig. 8B). These results indicate that the prechallenge antibody levels between the P. yoelii MSP-7 and the P. yoelii MSRP-2 groups were not significantly different.

FIG. 8.

Prechallenge antibody responses of mice in trials 1, 2, and 3 (A, B, and C, respectively). Values are indicated as optical density at 450 nm. Each bar represents the average reading for the experimental group at a 1:200 dilution.

In the third trial with complete Freund's adjuvant, the prechallenge antibody responses were quite similar, with the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group having an average reading of 0.697 and the P. yoelii MSP-7 group having an average reading of 0.72. The prechallenge antibody responses in the P. yoelii MSP-119 and MSP-183a groups had average readings of 0.494 and 0.442, respectively (Fig. 8C). Overall, the prechallenge antibody response in the complete Freund's adjuvant trial was slightly higher in the P. yoelii MSRP-2 and P. yoelii MSP-7 individual groups than that previously seen with the Ribi adjuvant. However, there were no statistically significant differences between the prechallenge antibody levels in the P. yoelii MSRP-2 group and those in the P. yoelii MSP-7 immunized group or between the groups of animals immunized with P. yoelii MSP-119 and P. yoelii MSP-183a.

DISCUSSION

Through a combination of the genome project and molecular approaches, there has been continuous discovery and characterization of proteins associated with the malaria parasite. Previously, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to identify proteins that associate with a portion of the amino-terminal 83-kDa proteolytic fragment of P. yoelii MSP-1 and characterized several of the homologues present in P. falciparum (22). In this study, we focused our attention on the characterization of the P. yoelii genes MSP-7 (homologue to MSP-7 originally described in P. falciparum) and MSRP-2.

Analysis of the genes revealed that they are 25% identical and 43% similar and lie adjacent to one another on the same contig (22). Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that P. yoelii MSRP-2 could be precipitated from radiolabeled parasite material and culture supernatants. P. yoelii MSRP-2 appears as a band of approximately 45 kDa, which corresponds to the molecular mass of the full-length protein. This was not the case when immunoprecipitation assays were performed with antisera specific for P. yoelii MSP-7. The protein was precipitated as a band of approximately 22 kDa, which is smaller than the predicted molecular mass of the full-length protein at 35.5 kDa, suggesting that it has undergone processing, a finding consistent with the processing that occurs with MSP-7 in P. falciparum (25).

It is unclear why the immunoprecipitation reactions with antisera directed against either MSRP-2 or MSP-7 fail to coprecipitate additional components of the MSP-1 complex (i.e., MSP-1 itself). The association between the proteins may be stabilized in some way while on the parasite surface and weaken once the molecules are shed into the culture supernatant, or they may be disrupted when the parasites are solubilized by the use of detergents in the immunoprecipitation buffers. With specific antisera directed against P. yoelii MSP-7 and P. yoelii MSRP-2, we have shown that these molecules are expressed on the surface of late-stage intraerythrocytic parasites colocalizing with MSP-1 and each other.

Protective immune responses are generated in mice immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2 but not P. yoelii MSP-7. When the challenge trials are compared, the group immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2 and complete Freund's adjuvant have statistically significant decreases in parasitemia and do not display the second wave of infection that was observed when the protein was administered in combination with Ribi as the adjuvant. In groups immunized with P. yoelii MSRP-2, there is not 100% survival of the animals, and the Ribi group exhibits higher parasitemia than the complete Freund's adjuvant groups. This presents one of the obstacles in malaria vaccine development. Complete Freund's adjuvant is the only adjuvant that has reliably induced protective immunity in monkeys, but it is not suitable for human use (13). Other groups have also demonstrated that the successful protection of mice in challenge experiments was dependent on the adjuvant, and in some cases protection was dependent on the genotype of the animal (11).

One potential reason for the increased protective immune responses resulting from immunization with P. yoelii MSRP-2 compared to P. yoelii MSP-7 is that significantly less P. yoelii MSP-7 is present on the surface of the parasite. However, real-time PCR analysis has suggested that the mRNA for P. yoelii MSP-7 is approximately twofold more abundant than the mRNA for P. yoelii MSRP-2 and that P. yoelii MSP-1 mRNA is approximately 3.7-fold more abundant than the mRNA for P. yoelii MSP-7 and 6.5- to 6.9-fold more abundant than the mRNA for P. yoelii MSRP-2 (data not shown).

One way to increase protection may be to consider a multicomponent vaccine composed of several antigens from the same or different stages of parasite development. Recently, administering mice a combination of P. yoelii MSPs 4 and 5 with the 19-kDa region of P. yoelii MSP-1 provided enhanced protection in mice compared to immunizing with P. yoelii MSPs 4 and 5 or P. yoelii MSP-119 alone (17). In preliminary studies, P. yoelii MSRP-2 was used to immunize animals in combination with the amino-terminal portion of P. yoelii MSP-183a or P. yoelii MSP-7, and the animals fared worse (data not shown). Prechallenge antibody levels do not seem to play a role in protection, as there was no significant difference between the levels of antibody in the protected and the unprotected groups of animals. Other possibilities for the observed protection may rely upon the isotype or avidity of the antibodies produced by immunization with the different proteins.

The precise role of the MSRP family members is unclear. The challenge data suggest that at least P. yoelii MSRP-2 may have a role in the invasion process. By blocking P. yoelii MSRP-2, one could be blocking the function of MSP-1 though its association with P. yoelii MSRP-2 on the surface of the parasite and inhibiting the ability of the parasite to invade cells. Alternatively, antibodies to the surface proteins might be causing the agglutination of the merozoites, thereby inhibiting their invasion. The mechanism(s) by which immunization with P. yoelii MSRP-2 provides protection needs to be examined further. The contribution of the other parts of the immune system, such as cell-mediated immunity, cannot be discounted. Examining the role or function of these various surface proteins will lead to a better understanding of the biology of the parasite and open new avenues for vaccine development.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anders, R. F., and A. Saul. 2000. Malaria vaccines. Parasitol. Today 16:444-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, C. G., L. Wang, T. Wu, and R. L. Coppel. 2003. Apical location of a novel EGF-like domain-containing protein of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 127:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black, C. G., T. Wu, A. R. Hibbs, and R. L. Coppel. 2001. Merozoite surface protein 8 of Plasmodium falciparum contains two epidermal growth factor- like domains. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 114:217-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackman, M. J., and A. A. Holder. 1992. Secondary processing of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) by a calcium-dependent membrane bound serine protease: shedding of the MSP133 as a noncovalently associated complex with other fragments of MSP1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 50:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackman, M. J., J. A. Chappel, S. Shai, and A. A. Holder. 1993. A conserved parasite serine protease processes the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62:103-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackman, M. J., H. G. Heidrich, S. Donachie, J. S. McBride, and A. A. Holder. 1990. A single fragment of a malaria merozoite surface protein remains on the parasite during red cell invasion and is the target of invasion inhibiting antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 172:379-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bustin, S. A. 2000. Absolute quantification of mRNA with real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 25:169-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper, J. 1993. Merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium. Parasitol. Today 9:50-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1993. A recombinant 15-kilodalton carboxyl- terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii yoelii 17Xl merozoite surface protein 1 induces protective immune response in mice. Infect. Immun. 61:2462-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1995. Humoral response to a carboxyl-terminal region of the merozoite surface protein-1 plays a predominant role in controlling blood-stage infection in rodent malaria. J. Immunol. 155:236-243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daly, T. M., and C. A. Long. 1996. Influence of adjuvants on protection induced by a recombinant fusion protein against malarial infection. Infect. Immun. 64:2602-2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etlinger, H. M., P. Caspers, H. Matile, H.-J. Schoenfeld, D. Stueber, and B. Takacs. 1991. Ability of recombinant or native proteins to protect monkeys against heterologous challenge with Plasmodium falciparum. Infect. Immun. 59:3498-3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good, M. F., D. C. Kaslow, and L. H. Miller. 1998. Pathways and strategies for developing a malaria blood stage vaccine. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:57-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holder, A. A., et al. 1987. Processing the precursor to the major merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 94:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holder, A. A., et al. 1999. Malaria vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1167-1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holder, A. A., and R. R. Freeman. 1981. Immunization against blood-stage rodent malaria with purified parasite antigens. Nature 294:361-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kedzierski, L., C. G. Black, M. W. Goschnick, A. W. Stowers, and R. L. Coppel. 2002. Immunization with a combination of merozoite surface proteins 4/5 and 1 enhances protection against lethal challenge with Plasmodium yoelii. Infect. Immun. 70:6602-6613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis, A. P. 1989. Cloning and analysis of the gene encoding 230-kilodalton merozoite surface antigen of Plasmodium yoelii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 36:271-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons, J. A., R. H. Geller, J. D. Haynes, J. D. Chulay, and J. L. Weber. 1986. Epitope map and processing scheme for the 195,000-dalton surface glycoprotein of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites deduced from cloned overlapping segments of the gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:2989-2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall, V. M., A. Silva, M. Foley, S. Crammer, L. Wang, D. J. McColl, D. J. Kemp, and R. L. Coppel. 1997. A second merozoite surface protein (MSP-4) of Plasmodium falciparum that contains an epidermal growth factor-like domain. Infect. Immun. 65:4460-4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBride, J. S., and H. G. Heidrich. 1987. Fragments of the polymorphic Mr 185,000 glycoprotein from the surface of isolated Plasmodium falciparum merozoites form an antigenic complex. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 23:71-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mello, K., T. M. Daly, J. Morrisey, A. B. Vaidya, C. A. Long, and L. W. Bergman. 2002. A multigene family interacts with the amino-terminus of plasmodium MSP-1 identified with the yeast two-hybrid system. Eukaryot. Cell 1:915-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller, L. H., M. F. Good, and D. C. Kaslow. 1998. Vaccines against the blood stages of falciparum malaria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 452:193-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills, K. E., J. A. Pearce, B. S. Crabb, and A. F. Cowman. 2002. Truncation of merozoite surface protein 3 disrupts its trafficking and that of acidic-basic repeat protein to the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1401-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pachebat, J. A., I. T. Ling, M. Grainger, C. Trucco, S. Howell, D. Fernendez-Reyes, R. Gunaratne, and A. A. Holder. 2001. The 22kDa component of the protein complex on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites is derived from a larger precursor, merozoite surface protein 7. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 117:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siddiqui, W. A., L. Q. Tam, K. J. Kraner, G. S. N. Hui, S. E. Case, K. M. Yamaga, S. P. Chang, E. B. T. Chan, and S. C. Kan. 1987. Merozoite surface coat precursor protein completely protects Aotus monkeys against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:3014-3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trucco, C., D. Fernandez-Reyes, S. Howell, W. H. Stafford, T. J. Scott-Finnigan, M. Grainger, S. A. Ogun, W. R. Taylor, and A. A. Holder. 2001. The merozoite surface protein 6 encodes for a 36kDa protein associated with the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 complex. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 112:91-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu, T., C. G. Black, L. Wang, A. R. Hibbs, and R. L. Coppel. 1999. Lack of sequence diversity in the gene encoding merozoite surface protein 5 of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 103:243-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]