Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne alphavirus that in humans causes an acute febrile illness characterized by fever, arthralgia, and rash. It is currently associated with large outbreaks in Asia, Africa, and islands of the Indian Ocean and has been introduced from these tropical regions into Europe, where local transmission has been recorded on two occasions. The underlying basis of the pathogenesis of CHIKV and related alphaviruses that produce similar symptoms remains unclear. By applying new techniques, for example, in vivo imaging in live animals and arthropods, we may improve our understanding of viral pathogenesis in vertebrates and viral replication in mosquitoes. This technical report describes the evaluation of a CHIKV–luciferase clone to visualize infection and dissemination in both Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and mice. In mosquitoes, luciferase activity was seen at 3 and 7 days post-infection in both head and abdomens. In vivo imaging of CHIKV–luciferase was detected in mice for up to 5 days post-infection at the site of inoculation with limited dissemination to the skeletal muscle.

Key Words: Chikungunya, Alphavirus, Luciferase, Mosquito

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a mosquito-borne alphavirus, first isolated in Tanzania in 1952 (Robinson 1955). Human infections result in chikungunya fever (CHIKF), an acute febrile illness characterized by fever, rash, arthralgia, and in some patients, persistent and recurrent arthritis-like symptoms lasting for months or occasionally years (Tesh 1982; Powers and Logue 2007). CHIKV is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa with a forest cycle of Aedes mosquitoes and nonhuman primates but sometimes emerges to cause large human outbreaks (Powers and Logue 2007). In Southeast Asia, CHIKV is also endemic and epidemic, but in this region it apparently exists only in an urban cycle consisting of humans and Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes (Thiboutot et al. 2010). During the 2005–2006 epidemic, a viral mutation enabled CHIKV to expand its vector host range by increasing the viruses' ability to infect Ae. albopictus mosquitoes (Tsetsarkin et al. 2007). There have been numerous cases of importation of CHIKF into nonendemic countries, and in September of 2010, cases of CHIKF in France occurred in patients with no travel history, indicating possible local transmission (Gould et al. 2010). This is the second time that CHIKV has been transmitted locally in Europe, the first being in Italy in 2007 (Enserink 2007, Rezza et al. 2007).

The potential for CHIKV to become a global health problem causing disease in both tropical and subtropical areas has prompted new research interest on therapeutics and vaccines. The pathogenesis of CHIKV in humans is not fully understood, although recent work with animal models has provided evidence of an immune-mediated pathology that results in myositis in skeletal muscles (Gardner et al. 2010, Higgs and Ziegler 2010). Experimental studies using an outbred mouse model in which animals develop an acute viremia and severe myositis in the skeletal muscle (Ziegler et al. 2008) have demonstrated a differential effect on mouse cytokine responses to CHIKV infection when CHIKV is delivered with mosquito saliva (Thangamani et al. 2010). The need to have a better understanding of viral replication in animals and mosquitoes has prompted the development of CHIKV infectious clones (ICs) that contain reporter gene sequences (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). In this report, we describe the construction of the first CHIKV–luciferase IC and the characterization of this clone in both mosquitoes and mice. This recombinant genome was infectious for Aedes mosquitoes when orally presented and allowed for visual evaluation of midgut infection and dissemination to secondary tissues in the vector. Further, post-infection in vivo imaging of the sites of viral replication was conducted in mice that demonstrated CHIKV replication at the site of infection for up to 5 days post-inoculation.

Materials and Methods

Construction of CHIKV–luciferase IC

A humanized Renilla luciferase reporter gene, derived from phRL-TK (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), was cloned into a CHIKV IC in a 5′ orientation relative to the structural cassette (Fig. 1). Briefly, an intermediate cloning construct was generated by first cloning the Renilla luciferase gene into a Sindbis virus (SINV) replicon via blunt-end ligation of cloning fragments following restriction endonuclease digestion and T4 polymerase treatment (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) of phRL-TK and pSinRep5 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). This intermediate construct designated p356.2 was generated to flank the luciferase gene with convenient restriction sites to facilitate ease of insertion into pCHIK-LR-5′-GFP (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006). The enhanced green fluorescent protein gene in the plasmid construct pCHIK-LR-5′-GFP was then replaced with the Renilla luciferase gene derived from p356.2 to generate pCHIK-LR-5′–Luciferse (CHIKV-LUC). All intermediate and final constructs were verified by sequence analysis. In vitro transcribed RNAs derived from this recombinant genome were generated using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), directly electroporated into BHK-21 cells, and harvested and aliquoted on day 2 post-electroporation. Aliquoted virus was stored at −80°C for use in these experiments. The titer of the stock virus was 106.5 tissue culture infectious dose50 (TCID50)/mL.

FIG. 1.

Gene map of chikungunya virus–luciferase (CHIKV-LUC).

In vitro infections and luciferase imaging

Vero cells were grown at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide in minimum essential medium, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2% sodium bicarbonate, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen). C6/36 cells (Ae. albopictus) were grown at 27°C in L15 media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% tryptose phosphate broth solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). For in vitro studies of CHIKV-LUC, a six-well tissue culture plate was seeded with C6/36 cells or Vero cells, and 48 h later, when cells reached confluence, they were infected with CHIKV-LUC at a concentration of 104.5 TCID50. Briefly, 100 μL of viral stock was added to each well and was allowed to incubate for 1 h at 27°C (C6/36) or 37°C (Vero cells). After incubation, the appropriate medium was added to each well. Cells were imaged in the six-well plate at 24 h post-infection (hpi). The cell culture plate was placed in a Xenogen In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS®) 200 Series (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) and images were immediately recorded before and after addition of the ViviRen substrate (Promega Corporation). Prior to substrate addition, cell medium was removed and fresh medium was added. ViviRen was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 10% FBS, and added to the tissue culture plate wells to a final concentration of approximately 1–0.1 nM. An exposure time of 1 s was used to visualize luciferase expression in cell culture.

Mosquito infections and luciferase imaging

Ae. aegypti (Rexville D strain Higgs white-eye) and Ae. albopictus (Galveston) mosquitoes were reared at 27°C and a relative humidity of 80% under a 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod, as previously described (Higgs 2004). Four to 6 days post-eclosion, female mosquitoes were fed an artificial blood meal using the Hemotek feeding system (Discovery Workshops, Accrington, United Kingdom) in an isolation glove box located in a Arthropod Containment Level 3 insectary. A 1:1 mixture of defibrillated sheep's blood (Colorado Serum Company, Boulder, CO) and virus stock, for a final titer of 104.5 TCID50/mL of CHIKV-LUC, was heated to 37°C and placed in the Hemotek feeder, and the membrane was placed on the mosquito containers. After feeding, mosquitoes were sorted, and fully engorged mosquitoes were transferred to an environmental chamber at 27°C and supplied with 10% sucrose ad libitum (Higgs 2004). At 3 and 7 days post-infection (dpi), mosquitoes were chilled and legs and wings were removed. A stock solution of the substrate ViviRen (0.24 mM) was intrathoracically inoculated to visualize the luciferase expression from the CHIK-LUC infection. Mosquitoes were placed into a six-well plate and visualized using a Xenogen IVIS instrument located in a biosafety level-3 laboratory. An exposure time of 5 s was used and images were taken 30–40 min following injection of substrate.

CHIKV-LUC infection and visualization in mice

Weaning (3–4 week old) CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were housed in an animal biosafety level-3 facility and all manipulations were performed in accordance with NIH, AAALAC, and UTMB standards for animal care and infection. Mice were anesthetized and virus was injected in the right rear footpad with 105.5 TCID50 of CHIKV-LUC in a total volume of 0.04 mL in PBS. At 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h and 5 dpi, mice were anesthetized and injected with the ViviRen substrate. The substrate was first dissolved in DMSO (0.37 mg in 10 μL of DMSO) and diluted in PBS with 10% FBS to a final concentration of 0.236 mM. Immediately prior to substrate injection, IVIS images of the mice were taken to confirm the lack of autofluorescence. ViviRen substrate was injected into each mouse in a final volume of 50 μL at a dose of approximately 1 mg/kg (Otto-Duessel et al. 2006). Immediately after substrate addition, mice were returned to the IVIS chamber and were imaged every minute for time course studies. For later experiments, the substrate was allowed to diffuse in the mice for 20 min before images were taken. This time point was chosen as it corresponds to the peak of luminescence in the mice. CHIKV 5′ GFP, described previously (Tsetsarkin et al. 2006), was used as a negative control and injected at the same concentration and location as the CHIKV-LUC. The exposure time for the images was 30 s and region of interest calculations were made using the IVIS Living Image Software (Caliper Life Sciences).

Results

Cell culture

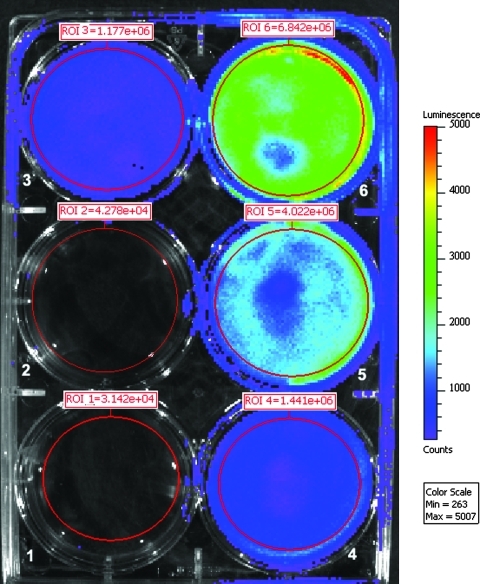

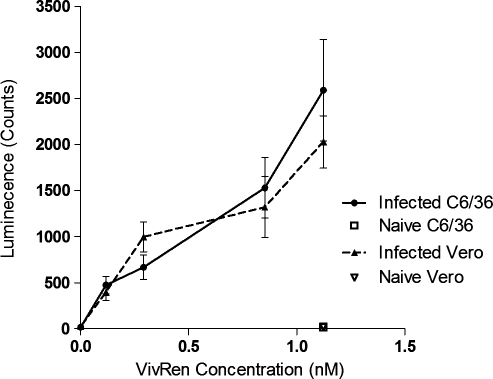

Infectious CHIKV-LUC virus caused luminescence and cytopathic effect in cultures of Vero cells at 24 and 48 hpi. Virus derived from the CHIKV-LUC construct replicated with similar kinetics to wild-type virus, with maximum titers of approximately 106.5 TCID50/mL 48 hpi. Luminescence was measured at both 24 and 48 hpi with the IVIS machine and signal was detected. To optimize the substrate concentration for detection in vitro, Vero and C6/36 cells were plated into six-well dishes and were infected with CHIKV-LUC at a concentration of 104.5 TCID50 (Fig. 2). At 24 hpi, ViviRen substrate was titrated (1–0.1 nM of ViviRen) on a series of infected monolayers; ViviRen-treated uninfected cells and substrate-negative CHIKV-LUC–infected cells were also included as controls. Similar luciferase activity was detected in both Vero and C6/36 cells. Luciferase activity was observed in a dose-dependent manner over the substrate concentrations evaluated, with peak luminescence counts being an average of 2590 for C6/36 cells and 2030 for Vero cells (Fig. 3). No luminescence was observed in virus- or substrate-negative controls.

FIG. 2.

C6/36 cells infected with CHIKV-LUC and imaged with ViviRen substrate added at 24 h post-infection. Cells were infected 24 h prior to addition of substrate. Well 1: control phosphate-buffered saline; wells 2–6: infected with CHIKV-LUC; wells 1 and 6: 1 nM ViviRen; well 2: no VivRen; well 3: 0.1 nM ViviRen; well 4: 0.25 nM ViviRen; well 5: 0.75 nM ViviRen.

FIG. 3.

Dose-dependent luminescence of in vitro luciferase activity in Vero and C6/36 cells. Cells were infected with CHIKV-LUC, and at 24 hpi, ViviRen substrate was added in the concentrations indicated. Luminescence was measured using the IVIS machine and average luminescence per well was calculated.

Imaging of Aedes mosquitoes

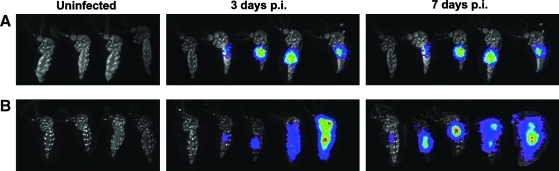

Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti are the principle vectors of CHIKV in the urban setting. To understand the rates of infection and dissemination, the CHIKV-LUC virus was used to visualize whole mosquitoes after being fed an artificial blood meal containing CHIKV-LUC. Imaging was performed on live mosquitoes following removal of legs and wings. It was observed that both Ae. albopictus and Ae. aegypti were susceptible to infection by the CHIKV-LUC and evidence of infection was observed as early as 3 dpi, with abdominal, thoracic, and head infection being detected by 7 dpi, whereas no intrinsic luminescence was observed in uninfected controls (Fig. 4). At 3 dpi, luminescence, indicative of CHIKV-LUC viral replication, was observed in 5 of 9 Ae. aegypti and 8 of 9 Ae. albopictus (Table 1). By visual examination, head or abdominal luminescence could be distinguished, but abdominal luminescence could not be further distinguished from that of the midgut or other parts of the abdomen. At 3 dpi, three Ae. albopictus had a disseminated infection, which included the whole body of the mosquito, and in five mosquitoes, luminescence was restricted to the midgut. At 7 dpi, 23 of 24 Ae. aegypti showed luminescence, with 15 mosquitoes displaying a disseminated infection pattern involving both the head and abdomen, 6 with only an abdominal infection, and 2 with only head infections. These data suggest that during the course of infection/dissemination, the extent/intensity of midgut infection may have declined over time. In Ae. albopictus mosquitoes at 7 dpi, 10 of 15 mosquitoes were infected, with 2 having a disseminated infection and 8 having only an abdominal infection. At 3 dpi, Ae. albopictus mosquitoes had a higher rate of infection when compared with Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, but at 7 dpi Ae. aegypti mosquitoes were more easily infected with CHIKV-LUC.

FIG. 4.

IVIS images of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus following oral infection of CHIKV-LUC. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus exhibited luciferase activity after infection with an artificial blood meal and injection of ViviRen. Mosquitoes were injected with ViviRen substrate at 3 or 7 days p.i. Images are a composite of individuals that represent the progression of infection in both Ae. aegypti (A) and Ae. albopictus (B). Uninfected mosquitoes injected with ViviRen substrate exhibited no luminescence and are the first mosquitoes in each panel. p.i., post-infection.

Table 1.

Mosquito Oral Infection and Dissemination

| Mosquito species | Day 3 p.i | Day 7 p.i |

|---|---|---|

| Aedes aegypti | ||

| Midgut only | 5/5 (100%) | 6/23 (26.1%) |

| Disseminated | 0/5 | 17/23 (73.9%) |

| Total | 5/9 (55.6%) | 23/24 (95.8%) |

| Aedes albopictus | ||

| Midgut only | 5/8 (62.5%) | 8/10 (80%) |

| Disseminated | 3/8 (37.5%) | 2/10 (20%) |

| Total | 8/9 (88.9%) | 10/15 (66.7%) |

Comparison of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus midgut infection and dissemination rates at 3 and 7 days postfeeding on a blood meal containing chikungunya virus–luciferase. At 30–40 min prior to imaging, ViviRen substrate was injected into the abdomen of the mosquito, and then infection and dissemination were quantified using the IVIS on whole live mosquitoes in six-well dishes. Images were rendered using the Living Image software.

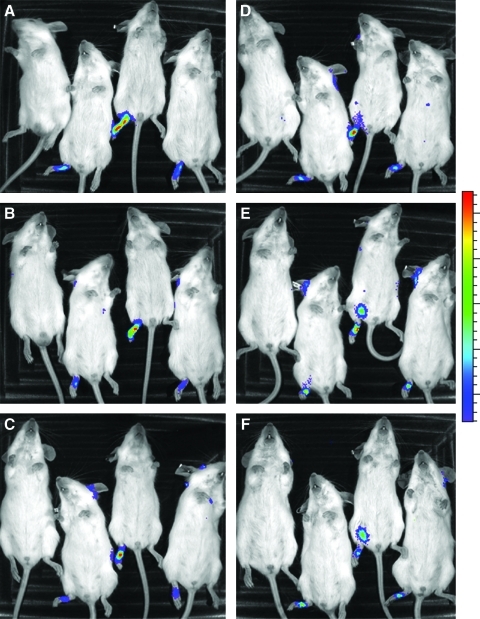

In vivo imaging in mice

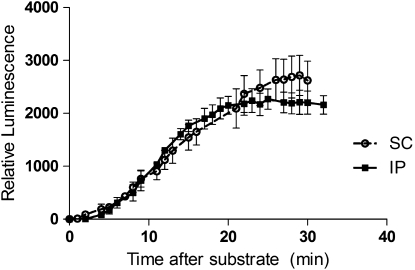

A mouse model of CHIKF has been developed to study the pathogenesis of CHIKV (Ziegler et al. 2008). To have a better understanding of the areas of viral replication in the mice, CHIKV-LUC was evaluated in this mouse model. First, it was important to determine the bioavailability of the ViviRen substrate and to optimize the delivery of the substrate. To do this, different time course studies and injection schemes were evaluated, including intraperitoneal (IP) and subcutaneous (SC) delivery methods. Intrinsic luminescence of the substrate was observed in control mice at the inoculation site (data not shown). To minimize this effect, ViviRen substrate was injected in the scruff of the neck, resulting in only minor intrinsic luminescence in the neck scruff. It was also observed that luminescence was visible for up to an hour after injection, but was completely undetectable by 12 hpi. Maximum luminescence was observed by 20 min post-ViviRen injection when delivered either IP or SC and began to decrease thereafter (Fig. 5). Local replication of CHIKV-LUC was observed in mice as early as 12 hpi and up to 7 dpi (Fig. 6). Dissemination was observed only in one mouse, which resulted in hind limb muscle infection. This began at 3 dpi and remained visible up to 5 dpi. It is possible that there was more dissemination in the mice, but that either it was in a deep tissue that could not be visualized or it was diffuse and did not result in a strong enough signal to be detected. SC infection of CHIKV-LUC in mice resulted in local replication for 2 days, but no signal was observed (data not shown). As previous works in the laboratory have shown that SC infection of CHIKV results in a disseminated disease, it is unclear why no luciferase activity was seen in these mice.

FIG. 5.

Luminescence intensity in murine hosts relative to time post-ViviRen injection, with the luminescence as a factor of time and injection location. Mice were injected with substrate either sub-cutaneously (SC) or intra-peritoneally (IP) and imaged approximately every 90 s.

FIG. 6.

IVIS images of mice infected with CHIKV-5′-LUC. Luciferase activity was observed as early as 12 h post-infection and up to 5 days post-infection. Pictures were taken at 20 min after injection of the substrate in accordance with peak luminescence intensity. The mouse pictured on the left on each panel was infected with CHIKV-GFP, but also received ViviRen at 20 min prior to imaging. Mice were imaged at 12 h (A), 24 h (B), 48 h (C), 72 h (D), 96 h (E), and 5 days (F) after inoculation of CHIKV-LUC in the right rear foot pad.

Discussion

In vivo imaging in whole animals is gaining acceptance in the field of infectious diseases. With the ability of this technology to be utilized in biocontainment laboratories, real-time knowledge of the pathology of highly pathogenic agents can be obtained using fewer animals. Limited published work of viral luciferase ICs exists for a comparison of these studies. Cook and Griffin (2003) conducted a similar study with SINV using IVIS imaging. The alphavirus, SINV, induces very different pathology in mice, causing neurological disease and limited mortality. Intranasal inoculation of SINV–luciferase clones in mice resulted in visualization of viral replication in the brain and neurons. This work affirmed the previous work with SINV. CHIKV infection has been shown to cause very little neurological disease when subcutaneously inoculated (Ziegler et al. 2008, Gardner et al. 2010, Morrison et al. 2011). Intranasal inoculation of CHIKV in mice has been shown to cause neuronal changes (Powers and Logue 2007, Wang et al. 2008). It is not surprising that neuronal involvement was not observed in the CHIKV-LUC–infected mice. If this experiment is repeated using an intranasal inoculation of CHIKV, albeit an unnatural route of CHIKV exposure, results similar to the previous SINV work might be expected. Other studies both with intra-cerebral and subcutaneous infection of luciferase tagged Sindbis virus showed dissemination to peripheral tissues that was age and heparin sulfate dependent in mice using IVIS technology at time points less than 24 hours post infection and 72 hours post infection (Ryman 2007a, Ryman 2007b). Work with both Eastern and Venezuelan equine encephalitis using luciferase encoding genomes and foot pad inoculations had very similar results as we have shown with CHIKV (Gardner 2008). While Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus disseminated out of the footpad to the draining lymph node, Eastern equine encephalitis virus did not. These reports further support our work with CHIKV and how it relates to other alphaviruses.

IVIS imaging in live mice has been also highly utilized in malaria and cancer research. Using reporter genes in malaria parasites has allowed researchers to visualize parasite load in both mosquito and mouse hosts. Luciferase-tagged parasites have been visualized in mouse liver using in vivo imaging and the parasite number calculated using IVIS has been correlated with the results of qRT–polymerase chain reaction analysis (Ploemen et al. 2009). In vivo imaging using microscopy has been also used to visualize GFP-tagged malaria parasites in the salivary glands of infected mosquitoes (Heussler and Doerig 2006). Tumors expressing a wide number of reporter genes have been used in combination with the IVIS to track the growth of tumors and their response to various treatments (Choy et al. 2003, Otto-Duessel et al. 2006).

Although GFP CHIKV clones are useful in mosquitoes, their ability to be effective reporters in mice in the IVIS system is limited because of intrinsic fluorescence of the mouse skin and fur, which results in a low signal-to-noise ratio. When working with luciferase constructs, there are a number of enzyme/substrate combinations that can be used. The Renilla luciferase enzyme has many features that make it a better choice when compared with other luciferase systems, including that it is independent of intracellular ATP, it is not secreted from the cell, and the coding region is small (Kimura et al. 2010). The use of the humanized Promega hRluc gene has increased luciferase expression in mammalian cells (Zhuang et al. 2001). In this report, we used the ViviRen substrate paired with a humanized Renilla luciferase enzyme, because recent reports showed the high bioavailability of this substrate compared with other coelenterazine anologs (Otto-Duessel et al. 2006). With further optimization, IVIS imaging using the CHIKV-LUC–infected mice may allow us to visualize deeper tissues and help describe the progress of pathogenesis of CHIKV infections.

This is the first report of using IVIS system to screen mosquitoes infected with CHIKV. The application of this technology in this way would allow for quick screening of mosquitoes that are still alive. In this report, we show that CHIKV-LUC was able to infect and disseminate in both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. Disseminated infection was defined as mosquitoes that showed luminescence activity in the head region. It is important to note that luminescence in the abdominal region could be from tissues outside of the midgut. Unfortunately, the legs and wings of the mosquitoes were not imaged with the whole mosquitoes. Using IVIS, we are quickly able to determine infection and dissemination rates in mosquitoes that would previously require labor- and time-intensive homogenization and titration. As the mosquitoes are still alive, we would also have the capability to take the mosquitoes and express saliva from them or select individual mosquitoes for further studies. This technology could be easily applied to other alphaviruses for understanding of their interaction with mosquito hosts. The ability to visually differentiate between infected and uninfected mosquitoes, whilst still alive, could greatly increase the efficiency of mosquito work and opens up the possibility to do specific labor-intensive studies on a specific subset of infected mosquitoes.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part supported by NIH grant R21 AI073389 (to S.H.) and NIH contract HHSN 2722000040I/HHSN27200004/D04 (to R.B.T.). S.A.Z. was supported by the Sealy Center for Vaccine Development. C.E.M. was supported by Centers for Disease Control Grant for Public Health Research Dissertation (R36) PAR07-231.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors state that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- Choy G. Choyke P. Libutti SK. Current advances in molecular imaging: noninvasive in vivo bioluminescent and fluorescent optical imaging in cancer research. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:303–312. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SH. Griffin DE. Luciferase imaging of a neurotropic viral infection in intact animals. J Virol. 2003;77:5333–5338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5333-5338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enserink M. Epidemiology: tropical disease follows mosquitoes to Europe. Science. 2007;317:1485a. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5844.1485a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner CL. Burke CW. Tesfay MZ. Glass PJ. Klimstra WB. Ryman KD. Eastern and Venezuelan equine encephalitis viruses differ in their ability to infect dendritic cells and macrophages: Impact of altered cell tropism on pathogenesis. J Virol. 2008;82:10634–10646. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01323-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J. Anraku I. Le TT. Larcher T, et al. Chikungunya virus arthritis in adult wild-type mice. J Virol. 2010;84:8021–8032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02603-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould EA. Gallian P. De Lamballerie X. Charrel RN. First cases of autochthonus dengue fever and chikungunya fever in France: From bad dream to reality! Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:1702–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heussler V. Doerig C. In vivo imaging enters parasitology. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.03.001. discussion 195–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. Care, maintenance, and experimental infection of mosquitoes. In: Marquardt WC, editor; Kondratieff B, editor; C.G. M, editor; Freier J, editor; Hagedorn HH, editor; Black WI, et al., editors. The Biology of Disease Vectors. 2. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 733–739. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S. Ziegler SA. A nonhuman primate model of chikungunya disease. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:657–660. doi: 10.1172/JCI42392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T. Hiraoka K. Kasahara N. Logg CR. Optimization of enzyme-substrate pairing for bioluminescence imaging of gene transfer using Renilla and Gaussia luciferases. J Gene Med. 2010;12:528–537. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison TE. Oko L. Montgomery SA. Whitmore AC, et al. A mouse model of chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto-Duessel M. Khankaldyyan V. Gonzalez-Gomez I. Jensen MC, et al. In vivo testing of Renilla luciferase substrate analogs in an orthotopic murine model of human glioblastoma. Mol Imaging. 2006;5:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploemen IH. Prudencio M. Douradinha BG. Ramesar J, et al. Visualization and quantitative analysis of the rodent malaria liver stage by real time imaging. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AM. Logue CH. Changing patterns of chikungunya virus: re-emergence of a zoonotic arbovirus. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 9):2363–2377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezza G. Nicoletti L. Angelini R. Romi R, et al. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryman KD. Gardner CL. Meier KC. Biron CA. Johnston RE. Klimstra WB. Early restriction of alphavirus replication and dissemination contributes to age-dependent attenuation of systemic hyperinflammatory disease. J Gen Virol. 2007a;88(Pt 2):518–529. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryman KD. Gardner CL. Burke CW. Meier KC. Thompson JM. Klimstra WB. Heparan sulfate binding can contribute to the neurovirulence of neuroadapted and nonneuroadapted Sindbis viruses. J Virol. 2007b;81:3563–3573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02494-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesh RB. Arthritides caused by mosquito-borne viruses. Annu Rev Med. 1982;33:31–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.33.020182.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangamani S. Higgs S. Ziegler S. Vanlandingham D, et al. Host immune response to mosquito-transmitted chikungunya virus differs from that elicited by needle inoculated virus. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiboutot MM. Kannan S. Kawalekar OU. Shedlock DJ, et al. Chikungunya: a potentially emerging epidemic? PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. 2010;4:e623. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsarkin K. Higgs S. McGee CE. De Lamballerie X, et al. Infectious clones of Chikungunya virus (La Reunion isolate) for vector competence studies. Vector-Borne Zoonot Dis. 2006;6:325–337. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsetsarkin KA. Vanlandingham DL. McGee CE. Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E. Volkova E. Adams AP. Forrester N, et al. Chimeric alphavirus vaccine candidates for chikungunya. Vaccine. 2008;26:5030–5039. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y. Butler B. Hawkins E. Paguio A, et al. A new age of enlightment. Promega Notes. 2001:79. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler SA. Lu L. da Rosa AP. Xiao SY, et al. An animal model for studying the pathogenesis of chikungunya virus infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]