Abstract

Background:

Pain management in the Emergency Department is challenging. Do we need to ask patients specifically about their pain scores, or does our observational scoring suffice? The objective of this study was to determine the inter-rater differences in pain scores between patients and emergency healthcare (EHC) providers. Pain scores upon discharge or prior to ward admission were also determined.

Methods:

A prospective study was conducted in which patients independently rated their pain scores at primary triage; EHC providers (triagers and doctors) separately rated the patients’ pain scores, based on their observations.

Results:

The mean patient pain score on arrival was 6.8 ± 1.6, whereas those estimated by doctors and triagers were 5.6±1.8 and 4.3±1.9, respectively. There were significant differences among patients, triagers and doctors (P< 0.001). There were five conditions (soft tissue injury, headache, abdominal pain, fracture and abscess/cellulites) that were significantly different in pain scores between patients and EHC providers (P<0.005). The mean pain score of patients upon discharge or admission to the ward was 3.3 ± 1.9.

Conclusions:

There were significant differences in mean patient pain scores on arrival, compared to those of doctors and triagers. Thus, asking for pain scores is a very important step towards comprehensive pain management in emergency medicine.

Keywords: emergency medicine, pain assessment, pain management, pain score, neurosciences

Introduction

Pain is a complex phenomenon in which an individual’s response is determined by the interactions of physical, psychological, cultural and sociodemographic factors (1). Pain itself is one of the most common presenting complaints in the Emergency Department (ED) (2). Pain assessment is of prime importance because it helps to determine the appropriate type of analgesia to administer and the urgency of the pain relief needed (3). Its contribution to improvements in patient satisfaction is also well-established (4).

Many studies have shown that assumptions about patient pain intensity are inaccurate in many settings, and documentation of pain assessment has improved pain management (5,6). Encouraging patients to communicate about their pain is also part of pain management (7). However, the assessment and management of pain in the ED is difficult and is a constant challenge to emergency healthcare providers, including emergency physicians (8).

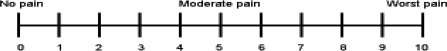

There are currently several reliable, valid pain assessment tools or pain scores available for use with adult patients in the acute pain setting. Although multidimensional pain scales are excellent, it can take up to 45 minutes to fully complete the questionnaires, rendering them impractical and cumbersome in the emergency setting (9). Therefore, a numeric rating scale (NRS) was used in this study, as the advantages include ease of administration and scoring, multiple response options and no age-related difficulties (Figure 1) (10). The words ‘no pain’ and ‘worst possible pain’ comprised the 0 and 10 ends of the scale, respectively.

Figure 1:

Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)

In Malaysia, the development of comprehensive emergency medical and trauma services is still in process. Most government hospital EDs are staffed by junior doctors with no postgraduate training or qualifications. Therefore, pain assessment and management are largely based on limited personal experience, as well as on the experiences of senior physicians.

The first step for pain management is to identify the patient who is in pain, so that the appropriate management can be delivered quickly. Do we need to ask patients specifically about their pain scores or do our observational scores suffice? The objective of this study was to determine the difference in pain scores between patients and emergency healthcare (EHC) providers. Pain scores upon discharge or prior to ward admission were also to be measured.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from September, 2004 to October, 2004 on varied shifts and days, based on convenience sampling in the ED of the Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL). ED HKL was a busy government hospital that receives an average of 650 to 700 patients per day and is managed by five to six medical officers per eight-hour shift. Ethical approval was obtained from the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Human Ethics Committee, as the researchers were from USM. Adult patients (age 18 years or older) with acute pain who presented to the ED HKL were included. Head injury cases with Glasgow Coma Scale ratings less than 15/15, intoxicated patients, haemodynamically unstable, significant language barrier, in a pain state of more than 72 hours, or were on any type of analgesia within the preceding four hours were excluded.

All patients provided informed consent prior to their participation in this study. Patients were given a formatted form and were asking to rate their pain scores after primary triage. Upon discharged to home or admission to the ward, the patient pain scores were assessed by the managing physicians. A horizontal 0 to 10 NRS was used to measure the pain score. Pain severity was defined in the following manner: mild, 1–4; moderate, 5–7; and severe, 8–10.

The EHC providers would rate the patients’ pain scores at the same time at the primary triage. The EHC providers were doctors and triagers. In our hospital, triagers were nurses or medical assistances with more than five years of experience working in the ED. Pain scores of the patients, doctors and triagers were obtained independently and blindly. At no time were the research personnel allowed to intervene in the patients’ management. As there were no proper guidelines for acute pain management in the ED, pain management depended on doctors’ professional experiences.

Based on the data collected, the chief complaint or diagnosis of the patients was divided into eight categories. It consists of soft tissue injury (STI), musculoskeletal pain (such as back pain), headaches, abdominal pains, abscesses or cellulitis, ischaemic heart disease (IHD), fractures and foreign bodies. The data were collected and analysed using SPSS (Version 12). T-tests were used to analyse the differences in pain score severity between patients and EHC providers. The non-parametric Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was used to compare the difference between patient and EHC provider pain scores based on the chief complaint/diagnosis. The patients’ pain scores were considered as a reference.

Results

A total of 107 patients were enrolled in this study. However, 20 patients had to withdraw from the study due to inadequate pain score data upon discharged or ward admission. Thus, there were 87 patients, of whom 56 (64.4%) were male and 31 (35.6%) were female. Among the male patients, 2 (3.6%), 39 (70%) and 15 (26.4%) were having mild, moderate and severe pain, respectively. Among the female patients, 21 (67.7%) and 10 (32.3%) of them were having moderate and severe pain. None of the female patients reported having mild pain. There was no statistical significant difference in pain severity scores between genders.

The mean age was 38.4 ± 11.3 years old; the range was from 19 to 65 years old. Patients of Malay ethnicity (46.0%) formed the majority of the study population, followed by Indian (39.1%) and Chinese (14.9%) patients. Most of patients presented with moderate pain (69%), followed by severe pain (28.7%). Upon discharge to the home or admission to the ward, the majority of patients were experiencing mild pain (51.7%), and almost half of them were having moderate pain (44.8%) (Table 1). The mean pain score of patients on arrival was 6.8 ± 1.6, whereas the mean pain scores of doctors and triagers were 5.6±1.8 and 4.3 ± 1.9, respectively. The mean differences between patients and doctors were 1.2 ± 1.6 and 2.5 ± 1.7 (Table 2). Paired t–tests showed significant differences between patients, triagers and doctors. The mean pain score of patients upon discharge or admission to the ward was 3.3 ± 1.9.

Table 1:

Frequency and percentage of patients’ pain scores by severity on arrival and upon discharge/ward admission

| Pain Severity (NRS) | On arrival n (%) | Upon discharge/ward admission n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 0 (0) | 3 (3.4) |

| Mild (1–4) | 2 (2.3) | 45 (51.7) |

| Moderate (5–7) | 60 (69.0) | 39 (44.8) |

| Severe 8–10 | 25 (28.7) | 0 (0) |

Table 2:

Result of paired t-tests between patients’ vs. doctors’ pain scores and patients’ vs. triagers’ pain scores on arrival

| Paired Differences | t | Df | Sig. 2-Tailed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | SEM | 95% CI | |||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Patients’ vs. Doctors’ pain scores | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 1.53 | 7.10 | 86 | <0.001 |

| Patients’ vs. Triagers pain scores | 2.5 | 1.7 | 0.18 | 2.08 | 2.79 | 13.6 | 86 | <0.001 |

There were significant differences between patients’ pain scores and EHC providers’ pain scores in relation to the chief complaint or diagnosis (Table 3 and 4). There were five conditions—STI, headache, abdominal pain, fracture and abscess/cellulites—that were related to significant differences in pain scores. Both doctors and triagers were underscoring these diagnoses.

Table 3:

Result of Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test comparing the differences between patients’ and doctors’ pain scores based on chief complaint/diagnosis

| Chief complaint/ Diagnosis | n (%) | z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft tissue injury | 30 (34.5) | −3.87 | <0.001 |

| Headache | 4 (4.6) | −2.00 | 0.046 |

| Musculoskeletal | 4 (4.6) | −1.89 | 0.059 |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (26.4) | −2.20 | 0.028 |

| Ischaemic Heart Disease | 5 (5.7) | −1.41 | 0.157 |

| Fracture | 13 (15.0) | −3.11 | 0.002 |

| Abscess/cellulitis | 6 (6.9) | −2.23 | 0.026 |

| Foreign body | 2 (2.3) | 1.41 | 0.157 |

Table 4:

Result of Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test comparing differences between patients’ and triagers’ pain scores based on chief complaint/diagnosis

| Chief complaint/ Diagnosis | n (%) | z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft tissue injury | 30 (34.5) | −4.15 | <0.001 |

| Headache | 4 (4.6) | −2.00 | 0.046 |

| Musculoskeletal | 4 (4.6) | −1.89 | 0.063 |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (26.4) | −4.05 | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic Heart Disease | 5 (5.7) | −1.41 | 0.157 |

| Fracture | 13 (15.0) | −3.20 | 0.001 |

| Abscess/cellulitis | 6 (6.9) | −2.00 | 0.046 |

| Foreign body | 2 (2.3) | −1.41 | 0.157 |

Discussion

Patients with pain comprise 60–70% of ED visits (11). It is a well-accepted fact that pain is an individual experience and should be established by the individual’s self-report of pain (7). The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisation (JCAHO) guidelines recommend the use of a pain score appropriate to the patient population to measure the intensity of a patient’s pain and to practice proper documentation. For adult populations, the JCAHO recommended the use of the ten-point NRS (12).

Good assessment and documentation lead to good pain management (12, 13). Good documentation should cover the initial and subsequent assessment (14). In our study, there were 20 patients who were withdrawn from the study due to no documentation of the pain score upon discharge or at ward admission. Poor documentation of subsequent pain assessments also occurs in developed countries (14).

The majority of the patients were male. Although there was no statistical significant difference in pain severity scores by gender, a higher percentage of female patients experienced severe pain, and none were experiencing mild pain. These data are consistent with current human findings regarding sex differences in the perception of experimental pain that indicate greater pain sensitivity among females compared to males (15). However, other research examining subjects in Singapore showed that the median pain score was not affected by gender (16).

People of the Malay ethnicity comprised the majority of the study population followed by the Indian and Chinese ethnicities. This ethnic distribution was not representative of the general Malaysian population (17), suggesting that financial constraint might have been a factor. HKL is a busy government hospital with minimum charges. With a charge of RM 1, all the hospital costs were covered, including consultations, medications and even CT scans.

Most of the patients presented with moderate pain, followed by severe and mild pain. Upon discharge to home or ward admission, only 3.4% of the patients were experiencing no pain. Yet, 44.8% of them were experiencing moderate pain, and none were experiencing severe pain. This is comparable with another local study that reported 14.3% and 33.3% of patients having severe and moderate pain upon discharge, respectively (18). This figure is suggestive of the clinical significance of pain undertreatment among our patients.

There is cause for concern in this scenario. The doctors anecdotally revealed that their major concern was in treating acute life-threatening conditions. Pain was considered as a minor condition and therefore less attention was thought to be needed. Another reason for this under-treatment of pain was ED overcrowding. ED overcrowding was a known independent factor for the undertreatment of pain (19). When the ED gets busy, staff may be less responsive to the needs of individual patients, and as a result, patients have a higher likelihood of experiencing delays in treatment and inadequate pain relief.

We detected a significant difference in pain scores among patients and EHC providers. We also found comparable results of greater underscoring by the triagers than by the doctors (6). A potential reason for this condition was that the teaching and training of pain management during the undergraduate level in medical school was inadequate (20); thus the highest education level for triager was a diploma. Pain assessment and management were among the least importance skills for them during their three-year course.

To look for possible factors that might account for the observed results, we examined differences based on the chief complaints. There were five conditions (soft tissue injury, headache, abdominal pain, fracture and abscess/cellulites) that were significantly different in pain score between the patients and EHC providers. Other conditions, such as musculoskeletal pain, ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and foreign bodies (FB), showed no significant difference in pain score. A potential reason for this was due to the small numbers of patients having those chief complaints.

Conclusions

There were significant differences between patients’ mean pain scores on arrival, compared to those of doctors and triagers. Clinical conditions that had significant differences in pain assessment were soft tissue injury, headache, abdominal pain, fracture and abscess/cellulites. It is obvious that more needs to be done for patients who present to the ED with pain. EHC providers need to be educated regarding pain assessment and pain management while not compromising the ED’s task of treating emergent, life-threatening conditions.

Introducing pain as a fifth vital sign, along with blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate and temperature, is a method to improve pain management. It also allows EHC providers to reassess patients’ pain scores sequentially to evaluate the effectiveness of the ED’s pain management. Thus, asking for pain scores is a very important step toward excellent and comprehensive pain management in Emergency Medicine.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions

Conception and design, KAB, NASNH, NM

Data-collection, assembly, analysis and interpretation: KAB, NASNH

Provision of study materials or patients: NASNH

Drafting of the article: KAB

Critical revision of article: NM

Final approval of the article: RA, NHNAR

Statistical expertise: RA

References

- 1.Melzack R, Wall ID, Ty TC. Acute Pain in an Emergency Clinic: Latency of Onset and Descriptor Patterns Related to Different Injuries. J Pain. 1998;14:33–34. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston CC, Gagnon AJ, Fullerton L. One Week Survey of Pain Intensity on Admission to and Discharge from the Emergency Department: A Pilot Study. J Emerg Med. 1998;16:377–382. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strange GR, Chen CH. Use of Emergency Departments by Elderly Patients: A Five-year follow-up Study. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:1157–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins JJ, Dunkel IJ, Gupta SK, Inturrisi CE, Lapin J, Palmer LN. Transdermal Fentanyl in Children with Cancer Pain: Feasibility, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetic Correlates. J Pediatr. 1999;134:319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voight L, Paice JA. Standardized Pain Flowsheet: Impact on Patient Reported Experiences after Cardiovascular Surgery. Am J Crit Care. 1995;4:308–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guru V, Dubinsky I. The Patient versus Caregiver Perception of Acute Pain in the Emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seattle, USA: International Association for Study of Pain; IASP Pain Terminology. [Internet] [cited 16/01/2009]. Available from: http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Pain_Definitions&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=1728. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ducharme J, Barber C. A Prospective Blinded Study on Emergency Pain Assessment and Therapy. J Emer Med. 1995;13:571–575. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducharme J. The Future of Pain Management in Emergency Medicine. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2005;23:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kendrick DB, Strout TD. The minimum clinically significant difference in patient-assigned numeric scores for pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebelt E, Levick N. Acute Pain Management, Analgesia, and Anxiolysis in the Adult Patient. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, editors. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study guide. 5th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2000. pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- 12.USA: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations pain standards; Healthcare safety and quality [Internet] [cited 20/01/2009]. Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/nr/rdonlyres/6c33fedb-bb50-4cee-950ba6246da4911e/0/setting_the_standard.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards FC. Establishing an emergency department pain management system. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2005;23:519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eder SC, Sloan EP, Todd KH. Documentation of ED patient pain by nurses and physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL. Sex, gender and pain: A review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim GH, Wee FC, Seow E. Pain management in emergency department. Hong Kong J. Emerg Med. 2006;13:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Statistic, Malaysia . Kuala Lumpur: Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad; 2002. Yearbook of Statistics, Malaysia. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamarul Aryffin B. Kubang Kerian: Universiti Sains Malaysia; 2006. A cross sectional study on pain management for acute orthopaedic fracture in emergency department, Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency Department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pusat Pengajian Sains Perubatan . Kubang Kerian: Universiti Sains Malaysia; 2008. Buku Panduan & Objektif Kursus Doktor Perubatan. [Google Scholar]