Abstract

Background:

The purpose of the study is to compare the two surgical methods (burr hole and craniotomy) used as treatment for superficial cerebral abscess and its outcome in terms of radiological clearance on brain CT, improvement of neurological status, the need for repeated surgery, and survival and morbidity at three months after surgery. This report is a retrospective case review of the patients who were treated surgically for superficial cerebral abscess in Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) and Hospital Sultanah Aminah (HSA) over a period of four years (2004 to 2007).

Methods:

Fifty-one cases were included in this study: 64.7% of patients were male and 35.5% were female. Most of the patients were Malay (70.6%); 28 patients (54.9%) had undergone craniotomy and excision of abscess, and the rest had undergone burr hole aspiration as their first surgical treatment.

Results:

This study reveals that patients who had undergone craniotomy and excision of abscess showed a significantly earlier improvement in neurological function, better radiological clearance and lower rate of re-surgery as compared to the burr hole aspiration group (P<0.05). However, with respect to neurological improvement at 3 months, morbidity and mortality, there is no significant difference between the two surgical methods.

Conclusion:

The significance of these findings can only be confirmed by a prospective randomised series. Further study will be required to assess the cost effectiveness, intensive care needs, and possibility of shorter antibiotic usage as compared to burr hole aspiration.

Keywords: burr hole aspiration cerebral abscess, craniotomy excision, neurosciences

Introduction

A brain abscess is defined as a focal suppurative process within the brain parenchyma (1). With advances in the development of new and more potent antibiotics and earlier diagnosis, we are seeing less intracerebral abscesses in Malaysia. Antibiotics, faster diagnostic confirmation and newer surgical methods have dramatically reduced the mortality rate from about 30–60% to 4–24% (2). However, it is still a challenge in treating this disease, which can still result in significant morbidity and mortality.

The basic principles of brain abscess treatment are early diagnosis, prompt surgical removal of pus, simultaneous eradication of the primary source and high-dose intravenous antibiotics. The definitive methods of surgical drainage are still not finalised (burr hole or craniotomy) and until now there has been no large prospective randomised controlled study done that can show which is the most effective surgical method.

The purpose of this study was to determine the association between two surgical methods used (burr hole and craniotomy) in the treatment of superficial cerebral abscess (SCA) as measured by survival of the patients, improvement of neurological status, radiological clearance of abscess, re-surgery and morbidity among the survivors.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective case review of patients who were treated surgically for SCA in Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL) and Hospital Sultanah Aminah (HSA) over a period of four years (2004 to 2007). HKL and HSA are both using the same computer database system in the operation theatre (OT). This system is called the Computerised Operation Theatre Database System (COTDS). With this Microsoft Excel system, data for all the patients who underwent neurosurgical procedures in the OT were recorded. The database consisted of the patient’s name, age, gender, registration number, date of operation, surgeon’s name and operative diagnosis. By typing the diagnosis “brain abscess” in the search box, a complete list of the patient’s data appeared on the computer screen. From these data, all patients who were diagnosed as brain abscess post-operatively were included in the study. By using their registration number, the patient’s notes and films were traced and studied. Those patients who fulfilled the criteria were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria

Intracranial supratentorial abscess >2.5 cm

Stage 3 or 4 abscess (Britt Staging)

Superficial margin of the abscess <1 cm from the cortex

First surgical treatment for supratentorial abscess was either burr hole aspiration or craniotomy excision

Patient’s notes and CT brain films were available in the record office

Exclusion criteria

Deep-seated or infratentorial abscess

Preoperative American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) >3

Less than 12 years old

Sample size calculations were calculated for each independent variable; the calculation used gave us the highest sample size using PS software (Dupport and Plummer). There were only 78 brain abscess patients available for this study in HKL and HAS. However, 27 patients did not fulfil the criteria and certain data were, rendering an actual sample size of 51 (n=51).

The burr hole and drainage procedure was defined as making a small opening in the skull using a twist drill (e.g. Hudson brace) up to a maximum diameter of 16 mm to allow a small opening of the dura mater so that a cannula could be inserted into the abscess to aspirate out the pus. In this procedure, pus was aspirated without any excision of its capsule. In this study, all the patients who had undergone the burr hole procedure and pus aspiration are categorised in the “burr hole” group.

Craniotomy and excision of the abscess was defined as a surgical procedure with a wide opening of the skull and dura, which exposed the full margin of the abscess. A high-speed craniotome was used to allow evacuation of pus and excision of the abscess wall under direct examination. In this study, all patients who had undergone craniotomy or craniectomy and excision of the abscess with its capsule were categorised in the same “craniotomy” group.

In this study the neurological status of the patients was assessed preoperatively and postoperatively using a Modified Rankin Scale (MRS). The neurological deficit after the first surgery was compared with the pre-operative status. Those patients who showed improvement in neurological status were categorised as the “yes” group. Those who did not have any neurological improvement following surgery were categorised as the “no” group.

Patients were also divided in two groups based on radiological clearance of the abscess. The first group was the “satisfactory” group where there was no residual abscess seen or only minimal residual abscess (<50% of pre-surgery volume). The second group exhibited residual abscess more than 50% of the pre-surgery volume (3).

Data from the case notes and films were studied and collected using a standardised questionnaire (see Appendix III). Analysis of the data was done using SPSS version 12.0 with the guide of our statisticians. Most of the data were categorical except for age, duration of illness and volume of abscess on brain CT. Descriptive analysis was performed for all data variables.

For all the study objectives, univariate analysis was performed using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test; P-value of < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Over the period of four years (from January 2004 until December 2007), seventy-eight patients with brain abscess were operated upon in the HKL and HSA neurosurgical OT. Out of these cases, only 51 cases of brain abscess fulfilled the criteria and were included in the study. Sixteen cases were excluded due to the exclusion criteria and 11 cases were excluded from this study due to incomplete data or missing case records. In this series the youngest patient included was 13 years old and the oldest was 65 years old. The mean age of the patients was 36.6 years old. Thirty-nine patients were below 50 years old (76.5%). Thirty-three patients (64.7%) were male and only 18 patients (35.3%) were female. The male to female ratio was 1.8:1.

Altered sensorium was noted to be the most common clinical presentation for brain abscess, occurring in most of the patients (82.4%) and followed by fever (66.7%), headache (62.7%), vomiting (39.2%) and focal neurological deficit (33.3%). The range of duration of symptoms prior to admission was mostly less than a week (66.7%); 21.6% of patients had symptoms for 1–2 weeks before seeking treatment in the hospital and 11.8% presented after 2 weeks. In the majority of cases, there was a predisposing factor (80.4%). In sixteen patients (31.4%), the source of infection was from the heart, either due to cyanotic heart disease or infective endocarditis. Eleven patients (21.6%) had history of trauma and/or head surgery; 4 patients (7.8%) had meningitis; 5 patients (9.8%) had ear infection (3 with mastoiditis) and 3 patients (5.9%) had lung abscess. In 19.6% of cases the source was not determined.

Based on the CT brain, the most common location for the abscess is the frontal region in 24 patients (47.1%). The other sites of abscess were in parietal (29.4%), temporal (13.7%), and occipital regions (9.8%). Out of 51 cases, 23 patients (45.1%) had undergone burr hole aspiration as their first surgical treatment. Among these, 11 patients required re-surgery for residual abscess. Eight underwent second burr hole aspiration and three underwent craniotomy excision. The other 28 patients (54.9%) had undergone craniotomy and excision of the abscess. One of the patients required second craniotomy excision due to recurrence of the abscess.

Only 38 patients (74.5%) had culture and sensitivity results available. Out of these, pus taken during the surgery was sterile in 22 patients (57.9%) and organisms were isolated in only 16 cases (42.1%). The most common organism seen is Streptococcus sp. (43.7%) followed by Staphylococcus sp. (25%).

Repeat brain CT was performed for all patients within one week after surgery to assess the residual volume of the abscess. Twenty-two patients (43.1%) had no residual abscess on brain CT. There were 6 patients (11.8%) who had significant residual abscesses. All of these were from the burr hole aspiration group and required second surgery within one week of the first surgery. The other 23 patients (45.1%) had minimal residual abscesses. However, 5 of these patients required a second surgery after one week due to expanding abscesses. One was from the craniotomy excision group and the rest were from the burr hole aspiration group.

Three patients died within one week after the first surgery (surgical mortality rate of 5.9%). Two were from the craniotomy group. Both of these patients presented with MRS grade 4. They had multiple co-morbid illnesses, namely uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension and heart disease. Brain CT showed large abscess (>5 cm) with significant midline shift and oedema. Craniotomy and evacuation were performed in an attempt to save the patients lives; however, they died a few days after the surgery despite aggressive medical and surgical therapy. The other patient in the burr hole group who died was a 62-year-old lady who experienced myocardial infarction after surgery. At 3-month follow-up, there were another 2 patients from the burr hole group who died due to sepsis and severe cyanotic heart disease. The total survival rate at 3 months was 46 patients (90.2%). Functional status of the patients was graded with MRS. Post-operative assessment of the patients revealed that 27 patients (52.9%) showed improvement in their MRS grades within a week after the first surgery. Improvement of neurological status was found to be greater in the patients who underwent craniotomy (71.4%) as compared with the burr hole group (30.4%). However, at 3-month follow up, neurological improvement was seen in 85.7% of patients from the craniotomy group and 82.6% from the burr hole group.

The majority of patients who underwent craniotomy excision showed satisfactory clearance of the abscess in brain CT (89.3%) but only 10 patients (43.5%) in the burr hole group displayed satisfactory clearance. This led to 11 out of 23 patients (47.8%) in the burr hole group requiring a second surgery, whereas in the craniotomy group only 1 patient (3.6%) underwent another surgery. This showed craniotomy and excision had a significantly better clearance as compared to burr hole aspiration (P<0.001) as well as a lower rate of re-surgery (P<0.001).

In this study, 27 patients (52.9%) showed significant improvement of neurological status within a week following surgery. Twenty out of 28 patients (71.4%) in the craniotomy group had significant improvement in their neurological status, which was higher than in the burr hole group (7 out of 23 patients, 30.4%). There was significant association between the two surgical methods and improvement of neurological status at one week (P=0.004). Patients who had undergone craniotomy and excision had earlier improvement in their neurological status compared to those who underwent burr hole and aspiration. However, at the end of 3 months after the surgery, a total of 39 patients (76.5%) already showed significant improvement in neurological status: twenty-two out of 28 patients (78.6%) in the craniotomy group and 17 out of 23 patients from the burr hole group (73.9%). There was no significant difference in the improvement of neurological status between the two surgical methods at 3-months follow-up (P = 0.70).

Among 28 patients who underwent craniotomy excision as their first surgical method, 2 patients (7.1%) died. In the other group, 3 (13.0%) out of 23 patients who underwent burr hole aspiration died. We found no statistically significant difference in the survival of the patients who were treated surgically either with craniotomy excision or burr hole aspiration (P = 0.65).

Discussion

The best method for treating cerebral abscess is still difficult to determine. Nonsurgical treatment with antibiotics alone is the least invasive. Heineman et al. were the first to suggest that brain abscesses might be successfully treated only with antibiotics (4). Rosenblum also reported a series of 67 cases managed and cured by antibiotics alone (5). However, antibiotics alone are usually insufficient in a large and well-capsulated abscess. Rousseaux reported a series of 15 out of 31 cases which were successfully treated by antibiotics alone but all were less than 2.5 cm (6). In view of this, cases with abscess <2.5 cm were excluded from this study. Another problem with management without surgical intervention is failure to determine culture and determine the sensitivity of the organism. Therefore, multiple broad-spectrum antibiotics had to be used to address all possible organisms. This is clearly a major disadvantage of nonsurgical treatment.

The two main surgical methods of treatment include burr hole aspiration and craniotomy excision of the abscess. The best approach remains controversial. Argument has persisted over the use of burr-hole aspiration versus craniotomy excision. Different authors have reported contradictory results.

As mentioned earlier, excellent outcomes have been reported in patients managed by burr hole aspiration (7,8, 9–12, 13). The aspiration approach offers a number of advantages: avoidance of general anaesthesia, access to multiple lesions without an increase in surgical complexity, and an ability to decompress lesions in eloquent areas as well as deep-seated locations. However, most of the series that show favourable results for burr hole aspiration are performed under CT-guided or image-guided stereotaxic aspiration. In Malaysia these facilities are not widely available and hence aspiration was performed when deemed appropriate based on measurements on contrasted brain CT film. However, in this study only superficial abscesses were studied; localisation of the abscess is not technically difficult, even for free-hand aspiration.

Some authors of recent studies have advocated craniotomy excision in the management of brain abscess. This surgical recommendation was based on their observation that despite satisfactory localisation, these abscesses were inadequately evacuated by burr hole aspiration. More cases treated with burr hole aspiration as compared to craniotomy required second or more surgeries. Complete evacuation of the abscess reduces the mass effect better and allows for better antibiotic penetration.

Males (64.6%) were more commonly affected than females (35.4%), at a ratio of 1.8:1. Jafri reported a similar finding in his series of 60 patients; he found that 66.7% of those affected were male, at a ratio of 2:1 (14). We only included patients aged more than 12 years old. The mean age was 36.6 years old. After 12 years of age, physiological status is similar to that of an adult and hence the surgical risk is also similar to that of the adult age group. Therefore only patients older than 12 years were included in this study. This minimised the bias in terms of age group with regard to the decision to pursue a certain method of surgery. In the adult age group, the majority of the patients are in their second or third decades of life. This result is comparable with most of the published series on brain abscess.

Altered sensorium is the most common presentation in our series (82.4%). However, the majority of patients have a Glasgow Coma Scale of 13–14 (59.2%). Other symptoms presented included fever (66.7%), headache (62.7%), vomiting (39.2%), focal neurological deficit (33.3) and seizure (17.6). Similar findings were seen in published local data (14).

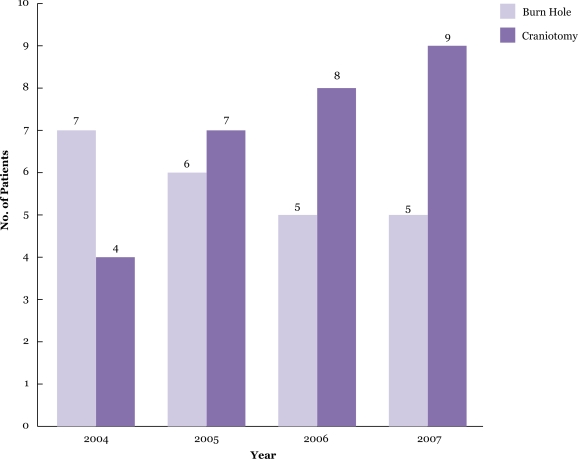

The decision to use a certain type of surgical methods in our unit was based on clinical and radiological findings, as well as neurosurgeon preference. Out of 51 patients included in this study, 23 patients underwent burr-hole aspiration as their primary surgery, representing 45.1% of cases. Another 28 patients (54.9%) had undergone craniotomy excision of abscess as their first surgical treatment. Previously burr hole and drainage was usually the surgical method of choice and craniotomy was only advocated for cases of refractory or residual abscess; however, the current trend in our centres favours craniotomy excision as first surgical treatment as long as the abscess is superficial and the patient is fit for major surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Mode of first surgery for SCA from 2004–2007

In terms of neurological status, we found that 71.4% of the patients from the craniotomy excision group showed improvement as measured by MRS within a week. In the burr hole aspiration group only 30.4% showed improvement (P=0.004). Patients who underwent craniotomy excision of abscess had earlier and better neurological improvement as compared to those who underwent burr hole aspiration. The reason for this is craniotomy allows total or more complete evacuation of the abscess with the capsule and the brain is adequately decompressed, which improves neuronal function. However, at 3 months follow-up, 76.5% and 73.9% of cases from the craniotomy and burr hole groups, respectively, already exhibited improvements in their neurological function. Statistical analysis revealed a p-value of 0.70 and hence no significant difference between the two groups in neurological function at 3-month follow-up (Table 1).

Table 1:

Association between surgical method and outcome

| Outcome |

Surgical Methods, n (%) |

χ2stat (df) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craniotomy Excision | Burr Hole Aspiration | |||

| Improvement of neurological status at one week | ||||

| Yes | 20 (39.2) | 7 (13.7) | 8.518 (1) | 0.004a |

| No | 8(15.7) | 16 (31.4) | ||

| Improvement of neurological status at three months | ||||

| Yes | 22 (43.1) | 17 (33.3) | 0.152 (1) | 0.696a |

| No | 6 (11.7) | 6 (11.7) | ||

| Radiological clearance | ||||

| Satisfactory | 25 (49.0) | 10 (19.6) | 12.307 (1) | <0.001a |

| Not satisfactory | 3 (5.9) | 13 (25.5) | ||

| Repeat surgery | ||||

| Yes | 1 (2.0) | 11 (21.6) | 13.744 (1) | <0.001a |

| No | 27 (52.9) | 12 (23.5) | ||

| Survival | ||||

| Alive | 26 (51.0) | 20 (39.2) | - | 0.647b |

| Death | 2 (3.9) | 3 (5.9) | ||

| Morbidity | ||||

| Independent | 23 (50.0) | 17 (37.0) | - | >0.95b |

| Dependent | 3 (6.5) | 3 (6.5) | ||

Pearson χ2 test applied

Fisher exact test applied

Surgical method was also found to be statistically significant for the clearance of abscess on brain CT (P< 0.001) (Table 1). Patients who underwent craniotomy have been noted to have a better abscess clearance on the CT scan. The advantage of craniotomy over the burr hole procedure is that it allows direct visualisation of the abscess and complete removal of the capsule. The stage of the abscess seen on the CT scan is also particularly important to determine the mode of surgery. In the cerebritis stage the capsule is not well formed and it is difficult to excise the abscess. Most authors advocated medical treatment with or without burr hole aspiration during this stage. Therefore only stage 3 or 4 abscesses (Britt staging) were included in our study.

In terms of re-surgery, more patients in the burr hole group had to undergo another operation in this study. There was a significant association between surgical method used and re-surgery (P <0.001). Patients in the burr hole group were noted to have a higher rate of re-surgery as compared to the craniotomy group. Re-surgery was closely related to the amount of residual abscess and the clinical response of the patients to medical treatment. The rate of re-surgery is proportionate to the amount of residual abscess remaining after the first surgery. Recurrence of pus collection can be attributed to ongoing seeding of pathogens from the primary source if it was not treated effectively. This is particularly true in some cases related to otorhinogenic causes and removal of the primary source by an otolaryngologist may be necessary.

Three months morbidity among survivors has no significant statistical association with method of surgery in this study (P>0.95). Patients with SCA had equal probability of having permanent disability or post-infective seizures later in life regardless of their primary surgical method. As stated in the literature, other prognostic factors were level of consciousness upon admission, immune deficiency, co-morbid illness and deep-seated abscess (15).

In a Russian series with 110 patients who underwent surgical treatment for brain abscess, they found that craniotomy and excision of the abscess was the most effective management. Sixty-three patients who underwent craniotomy excision had a favourable outcome as compared to the burr hole group (16). The advantages of the craniotomy excision were complete removal of the abscess with its capsule. Blind aspiration of the abscess renders is difficult to estimate the adequacy of the evacuation; furthermore, the capsule might collapse partially and prevent further aspiration and leave a residual abscess after surgery. This factor probably contributed to the slower improvement in neurological function in patients who underwent burr hole aspiration. Another risk is damage to the friable hyperaemic capsule, which causes bleeding.

Conclusion

The findings from this study suggest that craniotomy and excision is probably the better surgical method in the treatment of SCA. Compared to burr hole aspiration, craniotomy and excision has been shown to improve neurological status more quickly, with better abscess clearance as well as a reduced rate of re-surgery. However, this is not a prospective randomised series, so the results need to be verified through further studies.

Further study will be required to assess the cost effectiveness, intensive care needs, and possibility of short-term antibiotic usage as compared to burr hole aspiration in view of earlier neurological improvement.

There were some limitations in this study. The main limitation was the retrospective nonrandomised nature of the study. There were also different surgeons and two hospitals involved. Small sample size with 35% dropout (27/78) was another limitation. Only 51 patients were enrolled in this study due to incomplete data, missing case notes or exclusion criteria.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions

Conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, data collection and assembly: WMT

Provision of study material or patients: JSA

Final approval of the article: MSMH

References

- 1.Osenbach RK, Zeidman SM. Pyogenic Brain Abscess. Infections in Neurological Surgery, Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia(USA): Lippncott-Aven; 1999. pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hakan T, Ceran N, Erdem I, Berkman MZ, Göktaş P. Bacterial Brain Abscess: An evaluation of 96 cases. J Infect. 2006;52(5):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasdemir M. CT-guided stereotactic aspiration and treatment of brain abscesses: an experience with 24 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;125(1–4):58–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01401829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heineman H, Braude A, Soterholm JL. Intracranial suppurative disease. JAMA. 1971;218(10):1542–1547. doi: 10.1001/jama.218.10.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblum ML, Hoff JT, Norman D, Edwards MS, Berg BO. Nonoperative treatment of brain abscesses in selected high risk patients. J Neurosurg. 1980;52(2):217–225. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.52.2.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rousseaux M, Lesoin F, Destee A, Jomin M, Petit H. Developments in the treatment and prognosis of multiple cerebral abscesses. Neurosurgery. 1985;16(3):304–308. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderson D, Strong AJ, Ingham HR, Selkon JB. Fifteen-year review of the mortality of brain abscess. Neurosurgery. 1981;8(1):1–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyste GN, Hitchon PW, Menezes AH, VanGilder JC, Greene GM. Stereotaxie surgery in the treatment of multiple brain abscesses. J Neurosurg. 1988;69(2):188–194. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.69.2.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mampalam P. Trends in the management of bacterial brain abscess: a review of 102 cases over 17 years. Neurosurgery. 1988;23(4):451–458. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198810000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathisen GE, Meyer RD, George WL, Citron DM, Finegold SM. Brain abscess and cerebritis. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6(Suppl 1):S101–S106. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.supplement_1.s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller ES, Dias PS, Uttley D. CT scanning in the management of intracranial abscess: A review of 100 cases. Br J Neusurg. 1988;2(4):439–446. doi: 10.3109/02688698809029597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan H. Experience with 88 consecutive cases of brain abscess: A review of 100 cases. J Neurosurg. 1973;38(6):698–704. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.6.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephanov S. Large brain abscesses treated by aspiration alone. Surg Neurol. 1982;17(5):3338–3340. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jafri A. Clinical presentation and outcome of brain abscess over the last 6 years in a community based neurosurgical service. J of Clin Neurosci. 2001;8(1):18–22. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2000.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao F, Tseng MY, Teng LJ, Tseng HM, Tsai JC. Brain abscess: Clinical experience and analysis of prognostic factors. Surg Neurol. 2005;63(5):442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kariev MK, Kadyrbekov RT, Akhmediev MM, Akmedov SC, Khuzhaniiazov SB. Comparative analysis of surgical methods in the treatment of brain abscesses. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2001;2:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]