Abstract

Background:

Infertility has mental, social, and reproductive consequences. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of psychiatric intervention on the pregnancy rate of infertile couples.

Methods:

In an experimental and intervention-control study, 638 infertile patients who were referred to a university infertility clinic were evaluated; 140 couples (280 patients) with depression (from mild to severe) in at least one of the spouses were followed. All couples provided informed consent and were randomly numbered from 1 to 140. Those with even numbers were assigned to the psychological intervention before infertility treatment, and those with odd numbers were assigned to the psychological intervention during infertility treatment. Patients in the experimental group received 6–8 sessions of psychotherapy (individually) before beginning infertility treatment and were given Fluoxetine (antidepressant) at 20–60 mg per day during the psychotherapy period. The control group did not receive any intervention. Three questionnaires, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Stress Scale (Holmes-Rahe), and a sociodemographic questionnaire, were administered to all patients before and after treatment. The clinical pregnancy rate was compared between the two groups based on sonographic detection of gestational sac 6 weeks after the last menstrual period. The data were analysed by t test, X2 and logistic regression methods.

Results:

Pregnancy occurred in 33 (47.1%) couples in the treatment group and in only 5 (7.1%) couples in the control group. There was a significant difference in pregnancy rate between the treatment and control groups (X2= 28.318, P < 0.001). To determine the effectiveness of psychiatric interventions on pregnancy, a logistic regression analysis was used. In this analysis, all demographic and infertility variables were entered in a stepwise manner. The results showed that in the treatment group, Pregnancy in the treatment group was 14 times higher than the control group (95% CI 4.8 to 41.7). Furthermore, cause of infertility was an effective factor of pregnancy. The adjusted odds ratio in male factor infertility was 0.115 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.55) and in both factors (male and female) infertility was 0.142 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.76) compared with the unexplained group. In this study, no other variables had any significant effect on pregnancy.

Conclusion:

Based on the effectiveness of psychiatric interventions in increasing pregnancy rate, it is crucial to mandate psychiatric counselling in all fertility centres in order to diagnose and treat infertile patients with psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: behaviour therapy, depression, fertility, infertility, psychotherapy, pregnancy

Introduction

According to investigations, approximately 50 to 80 million people worldwide are currently experiencing infertility (1). Although the rate of infertility differs across studies, the average rate seems to be approximately 20%. Additionally, the inability to conceive a child may be the most difficult life experience that infertile couples have encountered (2).

Infertility has mental, social, and reproductive consequences, including depression, anxiety, aggressiveness, feelings of guilt, lack of self-esteem, lack of confidence, psychosomatic complaints, obsessions, relationship difficulties, and sexual dissatisfaction (3). Infertility is a bio-psycho-social phenomenon, meaning that it involves psychological, physiological, environmental, and interpersonal relation aspects. Consequently, infertility is not considered an organ function disorder and its other dimensions demand precise attention. In fact, infertility is a complex crisis of life that is a psychological threat and an emotional pressure. Perhaps due to this reason, psychological consequences of infertility had previously been assimilated into general grief reactions (4). Mental problems and even suicide attempts due to failure of infertility treatment have been described in many studies. Several investigations have found that stress levels are high in infertile couples and the negative effects of stress are considerably higher in infertile women than in their spouses. This finding could be interpreted as the result of the high pressure associated with diagnostic and treatment interventions as well as women’s responsibilities in regards to pregnancy and childbearing (5).

Today, there is a commonly held assumption that psychological illnesses and treatments may cause infertility. Psychological dimensions, physiological processes, environment, and interpersonal relations interact with each other and can predispose an individual to illness or health. Psychological treatment techniques including psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) are known to not only prevent and lessen various mental problems such as anxiety, depression, and phobia, but also to play a positive role in physical health and a successful pregnancy (4).

Sarrel et al. (6) reported that the psychiatric interview uncovered psychological conflicts. After 18 months of follow-up, 6 of the 10 women in couples who had been interviewed had become pregnant, and 1 of the 9 women in the control group had become pregnant. Domar et al. (7) suggested a model of psychological strain that reflects an acute stress reaction to the initial diagnosis and treatment overlaid with a chronic strain response to longer-term treatment. Behavioural treatment is associated with significant decreases in negative psychological symptoms (8). The psychological interventions have been found to be useful in alleviating depression in infertile couples before they received infertility treatment. The necessity of psychological counselling and interventions for infertile couples has been expressed with different indications (9,10).

The recognition of quality of life with specific attention to the effect of psychiatric interventions on the pregnancy rate of infertile persons is a recent development in Iran. The psycho-social model of illness may be an effective tool for approaching the problem of infertility.

Subjects and Methods

The study population included all infertile couples that visited Vali-Asr Infertility Clinic, Tehran University, for the first time between March 2003 and February 2006. Infertility was defined as at least 1 year of unprotected coitus without conception. The study was conducted in 2 stages. First, 638 infertile couples were assessed for depression in a cross-sectional study (Step 1 of the study).

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which includes 21 aspects of depression, was created by Beck in 1961 and the reliability (0.96) and validity (0.89) of this test was confirmed for Iranian people. Scores range as follows: no depression, 0–16; mild depression, 17–27; moderate depression, 28–34; and severe depression, 35–63 (11,12). In 1976, Holmes and Rahe created the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), a scale to measure stress, from a list of 43 stressful life events. In addition, the rate of stress was further determined using a 6-point assessment scale that classifies psychosocial factors that cause stress (13,14). In the current study, the BDI, the SRRS, and demographic-social questionnaires were used for data collection. When the BDI score was 17 or higher, an interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (15) was conducted by a clinical psychologist to confirm the diagnosis of depression.

All couples with a diagnosis of depression were asked to participate in Step 2 of the study. The 140 couples who agreed to participate provided informed consent and were randomly numbered 1–140. Those with even numbers were assigned to the psychological intervention before infertility treatment (Group 1) and those with odd numbers were assigned to the psychological intervention during infertility treatment (Group 2).

In Group 1, infertility treatment was postponed until completion of a 6-month psychological treatment with CBT, supportive psychotherapy by a clinical psychologist (individually), and 20 to 60 mg per day of fluoxetine depending on the severity of the depression and the participant’s condition. In Group 2, the same psychological treatment was provided during infertility treatment.

CBT included the recognition of negative thinking to help the participants distinguish phobia from reality and thereby change their cognitive structure. For example, infertile women often believe that they will never be able to have a child. Through exercises, this negative pattern was changed to “I will do anything to have a child of my own”. The behavioural techniques used included physical activity (including daily walking), muscle relaxation exercises, imagination exercises, expressing feelings, keeping a balanced diet, and planning free time according to one’s interests. After 6 months, both groups completed the BDI again.

Supportive psychotherapy assessed (a) the suitability of the psychological treatment, the cause of infertility, and the most suitable infertility treatment for each couple; (b) the depressed participants’ psychological and emotional responses to family, friends, and others; and (c) the depressed participants’ self-esteem in their relation to their partner, friends, colleagues, and others. Information regarding economic and other forms of social support was obtained using a semi-structured questionnaire that was modified for infertile couples. A test–retest analysis showed that the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.92. Data were analysed using the SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and logistic regression was performed to eliminate the effects of confounding factors.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as frequency (percentage) or mean (standard deviation). An independent sample t test was used to compare age, infertility, and marriage duration between control and treatment groups. Other demographic data were compared between study groups using a Chi-square test. A paired t test was used to compare the BDI at the beginning and end of the study.

To eliminate the confounding effect of demographic and other variables, a logistic regression analysis was used. In this analysis, study group, all of the demographic variables (age, education, occupation, marital duration), and all of the infertility variables (infertility duration, stress level, infertility cause, and treatment) were entered into a stepwise model. The criterion for entering a variable was a P value less than 0.05 and the criterion for removing a variable from the model was a P value greater than 0.1. All analyses were conducted in SPSS 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The current study included 70 infertile couples in the treatment group and 70 infertile couples in the control group. Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of the study groups. There was no significant difference in occupation between the treatment and control groups for men (P = 0.844) or women(P = 0.586). In addition, education level was similar in the treatment and control groups for men (P = 0.173) and women (P = 0.253). Among females, 38 (54.3%) in the treatment group and 51 (72.9%) in the control group experienced high levels of stress (P = 0.067). Among males, 39 (55.7%) in the treatment group and 41 (58.6%) in the control group suffered from stress (P = 0.805).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of the treatment and control groups

| Female | Male | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment n (%) | Control n (%) | Stats | Treatment n (%) | Control n (%) | Stats | ||

| Occupation | |||||||

| Employed | 9 (6.4%) | 36 (4.3%) | X2 = 0.412 P = 0.586 |

18 (12.9%) | 16 (11.4%) | X2 = 0.693 P = 0.844 |

|

| Housekeeper (Unemployed) | 61 (43.6%) | 64 (45.7%) | 52 (37.1%) | 54 (38.6%) | |||

| Education | |||||||

| Primary School | 19 (27.1%) | 26 (37.1%) | X2 = 4.077 P = 0.253 |

12 (17.1%) | 22 (31.4%) | X2 = 4.984 P = 0.173 |

|

| Middle–High School | 18 (25.7%) | 19 (27.1%) | 26 (37.1%) | 26 (37.1%) | |||

| Diploma | 26 (37.1%) | 23 (32.9%) | 23 (32.9%) | 17 (24.3%) | |||

| Degree and above | 7 (10.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 9 (12.9%) | 5 (7.1%) | |||

| Stress | |||||||

| Without | 32 (45.7%) | 19 (27.1%) | X2 = 7.148 P = 0.067 |

31 (44.3%) | 29 (41.4%) | X2 = 0.983 P = 0.805 |

|

| Low level | 14 (20.0%) | 26 (37.1%) | 20 (28.6%) | 20 (28.6%) | |||

| Medium level | 15 (21.4%) | 14 (20.0%) | 10 (14.3%) | 14 (20.0%) | |||

| High level | 9 (12.9%) | 11 (15.7%) | 9 (12.9%) | 7 (10.0%) | |||

Each group consisted of 70 participants.

The age of women ranged 19–41 years, with a mean of 26.57 (SD = 4.14) in the treatment group and 26.09 (SD = 4.69) in the control group (P = 0.517). The men’s age ranged 22–53 years, with a mean of 30.99 (SD = 4.42) in the treatment group and 31.24 (SD = 5.56) in the control group (P = 0.762). The average (SD) infertility duration in the treatment and control group was 5.81 (SD = 3.42) and 5.84 (SD = 4.42) years, respectively, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 9.66). The duration of marriage also did not significantly differ between the study groups (P = 0.715) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Age, infertility and marriage duration of the treatment and control groups

| Treatment Mean (SD) | Control Mean (SD) | Stats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Female) | 26.57 (4.14) | 26.09 (4.69) | t = 0.649, P = 0.517 |

| Age (Male) | 30.99 (4.42) | 31.24 (5.56) | t = 0.303, P = 0.762 |

| Duration of marriage | 6.29 (3.52) | 6.54 (4.50) | t = 0.366, P = 0.715 |

| Duration of infertility | 5.81 (3.42) | 5.84 (4.42) | t = 0.043, P = 0.966 |

Each group consisted of 70 participants.

The causes and treatments of infertility are presented in Table 3. Male factor infertility was observed in 22 (31.4%) couples in the treatment group and 24 (34.4%) couples in the control group. The cause of infertility was similar in both groups (P = 0.166). Furthermore, couples in both groups followed the same infertility treatment route (P = 0.605).

Table 3:

Cause and infertility treatment in the treatment and control groups

| Treatment n(%) | Control n(%) | Stats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infertility treatment | |||

| Induction of ovulation | 18 (25.7%) | 13 (18.6%) | X2=3.623 P = 0.605 |

| IUI | 14 (20.0%) | 9 (12.9%) | |

| ART | 22 (31.4%) | 24 (34.3%) | |

| Laparoscopy + hysteroscopy | 10 (14.3%) | 15 (21.4%) | |

| Donor oocyte / embryo | 3 (4.3%) | 4 (5.7%) | |

| Surgical treatment of the husband | 3 (4.3%) | 5 (7.1%) | |

| Cause of infertility | |||

| Male | 22 (31.4%) | 24 (34.3%) | X2=5.079 P = 0.166 |

| Female | 25 (35.7%) | 31 (44.3%) | |

| Both | 14 (20.0%) | 10 (14.3%) | |

| Unexplained | 9 (12.9%) | 5 (7.1%) | |

Each group consisted of 70 participants.

Abbreviation: ART = assisted reproductive technology (in vitro fertilization), IUI = intrauterine insemination

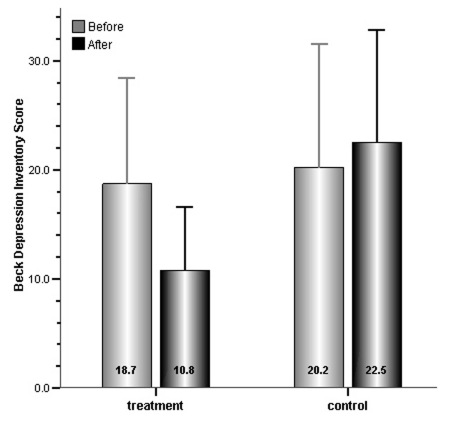

Results of the BDI are presented in Figure 1. Psychological intervention in the treatment group significantly decreased the depression score from 18.7 (SD = 9.7) to 10.8 (SD = 5.8) (P < 0.001). The stress score in control group was 20.2 (SD = 11.3) before and 22.5 (SD = 10.3) at the end of the study; however, the difference was not significant (P = 0.149).

Figure 1:

Beck depression score at the beginning and the end of the study for both treatment and control groups. The depression score significantly decreased in the treatment group (P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference in the control group (P = 0.142).

Finally, pregnancy occurred in 33 (47.1%) couples in the treatment group and in only 5 (7.1%) couples in the control group. There was a significant difference in pregnancy rate between the treatment and control groups (X2 = 28.318, P < 0.001). The various pregnancy methods are presented in Table 4.

Table 4:

Pregnancy and pregnancy type in the treatment and control groups

| Treatment n(%) | Control n(%) | Stats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | |||

| Not pregnant | 37 (52.9%) | 65 (92.9%) | X2 = 28.318 P < 0.001 |

| Pregnant | 33 (47.1%) | 5 (7.1%) | |

| Type of Pregnancy | |||

| Spontaneous pregnancy | 9 (27.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| ART | 8 (24.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Laparoscopy-hysteroscopy | 1 (3.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | |

| Ovulatory stimulation | 9 (27.3%) | 3 (60.0%) | |

| IUI | 5 (15.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Surgical treatment of the husband | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

Each group consisted of 70 participants.

Abbreviation: ART = assisted reproductive technology (in vitro fertilization), IUI = intrauterine insemination

To determine the effectiveness of psychiatric interventions on pregnancy, logistic regression analysis was used. In this analysis, all demographic and infertility variables were entered in a stepwise manner. The results showed that psychiatric intervention was the greatest predictor of occurrence of pregnancy. In the treatment group, pregnancy in the treated group was 14 times higher than the control group (95% CI 4.8 to 41.7) (Table 5). In addition to the psychological intervention, cause of infertility was an effective factor of pregnancy. The rate of pregnancy in male factor infertility was 0.115 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.55) and in both factors (male and female) infertility was 0.142 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.76) which were less than in the unexplained group. In this study, no other variables had a significant effect on pregnancy.

Table 5:

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio of pregnancy

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR |

95.0% CI |

P value | OR |

95.0% CI |

P value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Psychiatric intervention | 11.595 | 4.166 | 32.268 | <0.001 | 14.071 | 4.750 | 41.677 | <0.001 |

| Cause of Infertility | ||||||||

| Male factor | 10.135 | 0.036 | 0.509 | 0.003 | 0.115 | 0.024 | 0.548 | 0.007 |

| Female factor | 0.355 | 0.107 | 1.177 | 0.090 | 0.429 | 0.101 | 1.810 | 0.249 |

| Both | 0.197 | 0.046 | 0.838 | 0.028 | 0.142 | 0.027 | 0.762 | 0.023 |

| Constant | 0.249 | 0.063 | ||||||

Discussion

The present study was designed as a randomised clinical trial. A review of the literature revealed no published study of the synergistic effects of medication and psychological treatment in infertile participants in an oriental society. The results of this study showed that psychiatric and psychological intervention at middle- and high-school educated (men group), duration of infertility of less than 5 years, and unexplained cause of infertility leads to an increased pregnancy rate.

Matsubayashi et al. (15) reported that depression was more common among infertile than among fertile or pregnant women. Furthermore, both Newton et al. (16) and Wischmann et al. (17) reported depression to be higher among infertile women than infertile men that it could be a reason for the loss of self-confidence in their depressed participants. In a recent study, 81.3% of depressed infertile participants reported that the main stressor leading to their depression was relatives’ comments about their infertility (18).

The results of the present study showed that the chance of pregnancy increases as levels of stress decrease. Cwikel et al. reported that psychological factors such as stress and anxiety can lead to changes in the heart and cortisol hormone (19). Moreover, the results of some investigations showed a significant correlation between the adrenaline hormone and depression. Specifically, women who were in the in vitro fertilisation (IVF) circle in the Oocyte Pick Up–Embryo Transfer (OPU–ET) time demonstrated changes in their adrenaline and noradrenaline hormone. A comparison between pregnant women using IVF and women who had treatment failure showed that there is a difference in the level of these hormones in their blood; this may lead to the change in the rate of pregnancy in infertile women. However, this association is complicated by the effect of social and psychological stresses on IVF-ET success (20–22). Although some studies do not confirm the relation between stress and infertility (23,24), stress can be decreased using cognitive-behavioural interventions (especially during IVF-ET), thus increasing the chance of pregnancy (25,26). The finding of this research confirms that of other research. Overall, stress may be an important element in infertility and decreasing stress may increase the chance of pregnancy among infertile couples.

The results of this study showed that 47.1% of the treatment group and 7.1% of the control group became pregnant. The increase in the chance of pregnancy in the treatment group (40%) demonstrates the effect of psychiatric and counselling interventions on these patients. Domar et al., Terzioglu, and Newton et al. showed that psychiatric and counselling interventions led to significant decreases in anxiety and depression and increases in the chance of pregnancy (6,27,28); there is a complex relation between stress and infertility. One study showed that 41.9% of those in a psychotherapy group, 13.5% of those in a control group, and 42% of those in a cognitive-behavioural consulting group became pregnant (29). Hosaka et al. and Kupka et al. reported that psychological consulting in 14% of cases is conducive to spontaneous pregnancy and that it can be a consequence of reduced stress (30,31). Other reports have also demonstrated that psychiatric and counselling interventions (behavioural, cognitive, psychotherapy) conducted during treatment, diagnosis, and especially before IVF result in positive pregnancy tests. The use of psychiatric and counselling interventions increases the pregnancy chance in the following 6 months (32–39). Although Yong et al. did not confirm this relationship, even for people who believe that the advice in the first IVF cycle is ineffective; however, this type of study is of limited number (40). The findings of the present study confirm those of other research. Psychiatric and counselling interventions have an important role in curing infertility and lead to increased pregnancy success. Therefore, psychiatric and counselling interventions must accompany infertility treatments to increase the chance of pregnancy success and improve the mental health of infertile couples.

Conclusion

Psychological interventions to increase reproductive and infertility treatment success is related to stress reduction and treatment of psychiatric disorders (including anxiety and depression), and this approach tends to improve the quality of life in the infertile couples. Thus, it can be concluded that psychological intervention prior to infertility treatment was useful in infertile couples.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our appreciation to the Deputy Investigator of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for providing the financial support for this investigational plan, and all personals of Vali-Asr Reproduction Health Research Center for their kind contributions and cooperation.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

Conception and design, collection and assembly of data, drafting of the article: NA

Obtaining of funding: AAN

Provision of patients, administrative, technical, or logistic support: NA, AAN

Statistical expertise Analysis and interpretation of the data: ARF, MMN

Final approval of the article: FR, AAN

References

- 1.Rojuei M. Cognitive and behavioral treatments at infertility patients [Master’s thesis] Tehran (IR): Islamic Azad University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams KE, Marsh WK, Rasgon NL. Mood disorders and fertility in women: A critical review of the literature and implications for future research. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13(6):607–616. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukse MP, Vace NA. Grief, depression, and coping in women undergoing infertility treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(2):245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menning BE. The emotional needs of infertile couples. Fertil Steril. 1980;34(4):313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domar AD, Clapp D, Slawsby EA, Dusek J, Kessel B, Freizinger M. Impact of group psychological interventions on pregnancy rates in infertile women. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(4):805–811. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarrel P, DeCherney AH. Psychotherapeutic intervention for treatment of couples with secondary infertility. Fertil Steril. 1985;43(6):897–900. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)48618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg B, Wilson J. Psychological functioning across stages of treatment for infertility. J Behav Med. 1991;14(1):11–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00844765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domar AD, Zuttermeister PC, Seibel M, Benson H. Psychological improvement in infertile women after behavioral treatment: A replication. Fertil Steril. 1992;58(1):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramezanzadeh F, Abedinia N. Anxiety and depression in infertility. Tehran, Iran: Tehan University of Medical Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noorbala AA, Ramazanzadeh F, Malekafzali H, Abedinia N, Forooshani AR, Shariat M, et al. Effects of a psychological intervention on depression in infertile couples. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;101(3):248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooshan R. The surveying of comparison the rate of prevalence depression and anxiety between shahed and non shahed students of university [Master’s thesis] Tehran (IR): Tarbeyat Modares University; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karam-Sobhani R. The surveying prevalence of depression in Isfahan [Master’s thesis] Tehran (IR): Tarbeyat Modares University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan HI, Sadoc BJ. In: Synopsis of psychiatric: Behavioural Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. Pourafkari N, translator. Tehran, Iran: Azadeh Co; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsubayashi H, Hosaka T, Izumi S, Suzuki T, Makino T. Emotional distress of infertile women in Japan. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(5):966–969. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton CR, Hearn MT, Yuzpe AA. Psychological assessment and follow-up after in vitro fertilization: Assessing the impact of failure. Fertil Steril. 1990;54(5):879–886. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wischmann T. Psychological aspects of fertility disorders. Urologe A. 2005;44(2):185–194. doi: 10.1007/s00120-005-0779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noorbala AA, Ramezanzadeh F, Abedinia N, Bagheri SA, Jafarabadi M. Study of psychiatric disorders among fertile and infertile women and some predisposing factors. J Fam Reprod Health. 2007;1(1):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cwikel J, Gidron Y, Sheiner E. Psychological interactions with infertility among women. Eur J Obstetric Gynecologic Reprod Biol. 2004;117(2):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ardenti R, Campari C, Agazzi L, LA Sala GB. Anxiety and perceptive functioning of infertile women during in-vitro fertilization: Exploratory survey of an Italian sample. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(12):3126–3132. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.12.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smeenk JM, Verhaak CM, Vingerhoets AJ, Sweep CG, Merkus JM, Willemsen SJ, et al. Stress and outcome success in IVF: The role of self-reports and endocrine variables. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):991–996. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koryntova D, Sibrtova K, Klouckova E, Cepicky P, Rezabek K, Zivny J. Effect of psychological factors on success of in vitro fertilization. Ceska Gynekol. 2001;66(4):264–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovely LP, Meyer WR, Ekstrom RD, Golden RN. Effect of stress on pregnancy outcome among women undergoing assisted reproduction procedures. South J Med. 2003;96(1):548–551. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000054567.79881.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bringhenti F, Martinelli F, Ardenti R, La Sala GB. Psychological adjustment of infertile women entering IVF treatment: Differentiating aspects and influencing factors. Acta Obstet Scand. 1997;76(5):431–437. doi: 10.3109/00016349709047824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Facchinetti F, Tarabusi M, Volpe A. Cognitive-behavioral treatment decrease cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reaction to stress in women waiting for assisted reproduction. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarabusi M, Facchinetti F. Psychological group support attenuates distress of waiting in couples scheduled for assisted reproduction. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecologic. 2004;25(3–4):273–279. doi: 10.1080/01674820400017905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terzioglu F. Investigation into effectiveness of counseling on assisted reproductive techniques in Turkey. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;22(3):133–141. doi: 10.3109/01674820109049965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton CR, Hearn MT, Yuzpe AA, Houle M. Motives for parenthood and response to failed in vitro fertilization: Implication for counseling. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1992;9(1):24–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01204110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domar AD, Friedman R, Zuttermeister PC. Distress and conception in infertile women: A complementary approach. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1999;54(4):196–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosaka T, Matsubayashi H, Sugiyama Y, Izumi S, Makino T. Effect of psychiatric group intervention on natural-killer cell activity and pregnancy rate. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(5):353–356. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kupka MS, Dorn C, Richter O, Schmutzler A, van der Ven H, Kulczycki A. Stress relief after infertility treatment—Spontaneous conception, adoption, and psychological counseling. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Rerod Biol. 2003;110(2):190–195. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(03)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boivin J. A review of psychosocial interventions in infertility. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(12):2325–2341. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Place I, Laruelle C, Kennof B, Revelard P, Englert Y. What kind of support do couples expect when undergoing IVF treatment? Study and perspectives. Gynecol Obstetric Fertil. 2002;30(3):224–230. doi: 10.1016/s1297-9589(02)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eugster A, Vingerhoets AJ. Psychological aspects of IVF: A review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(5):575–589. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00386-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hart VA. Infertility and the role of psychotherapy. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(1):31–41. doi: 10.1080/01612840252825464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryson CA, Sykes DH, Traub AI. In vitro fertilization: A long-term follow-up after treatment failure. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2000;3(3):214–220. doi: 10.1080/1464727002000199011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emery M, Beran MD, Darwiche J, Oppizzi L, Joris V, Capel R, et al. Results from a prospective, randomized, controlled study evaluating the acceptability and effects of routine pre-IVF counseling. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2647–2653. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukse MP. The effect of group counseling on the frequency of grief reported by infertile couples. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1985;14(6 Suppl):67s–70s. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1985.tb02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNaughton-Cassill ME, Bostwick JM, Arthur NJ, Robinson RD, Neal GS. Efficacy of brief couples support groups developed to manage the stress of in vitro fertilization treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(10):1060–1066. doi: 10.4065/77.10.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yong O, Martin C, Thong J. A comparison of psychological functioning in women at different stages of in vitro fertilization treatment using the mean affect adjective check list. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2000;17(10):553–556. doi: 10.1023/A:1026429712794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]