Abstract

A nonarteriosclerotic cardiomyopathy is increasingly seen in obese patients. Seeking a rodent model, we studied cardiac histology, function, cardiomyocyte fatty acid uptake, and transporter gene expression in male C57BL/6J control mice and three obesity groups: similar mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) and db/db and ob/ob mice. At sacrifice, all obesity groups had increased body and heart weights and fatty livers. By echocardiography, ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) of left ventricular diameter during systole were significantly reduced. The Vmax for saturable fatty acid uptake was increased and significantly correlated with cardiac triglycerides and insulin concentrations. Vmax also correlated with expression of genes for the cardiac fatty acid transporters Cd36 and Slc27a1. Genes for de novo fatty acid synthesis (Fasn, Scd1) were also upregulated. Ten oxidative phosphorylation pathway genes were downregulated, suggesting that a decrease in cardiomyocyte ATP synthesis might explain the decreased contractile function in obese hearts.

1. Introduction

Heart disease is a major consequence of obesity, which is in turn strongly associated with major risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and sleep-disordered breathing [1]. However, studies increasingly suggest that obesity also has direct effects on the heart that may not result from atherosclerosis [2]. Abundant evidence shows an association between obesity and structural and functional changes in the heart in both humans and animals. Many of these changes, such as left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, left atrial (LA) enlargement, and subclinical impairment of LV systolic and diastolic function, are believed to be precursors of more overt forms of cardiac dysfunction and heart failure [2]. The data suggest that long-standing severe obesity may eventually lead to heart failure, and several studies suggest that patients with fatty liver are particularly subject to cardiac complications [3, 4]. These observations led us to the hypothesis that, as with obesity-associated fatty liver [5], obesity would cause upregulation of facilitated long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) uptake by cardiomyocytes, leading to ectopic triglyceride accumulation in the heart and a consequent cardiomyopathy. To test that hypothesis, we examined three murine obesity models: C57BL/6J mice chronically fed a high-fat diet, leptin-deficient ob/ob mice, and leptin-receptor-deficient db/db mice, with a combination of functional, histologic, biochemical, and molecular studies. Facilitated uptake of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) by cardiomyocytes, heart weights and left ventricular mass, and cardiac triglyceride content were increased and cardiac ejection fractions decreased in all three models. These results suggest that a general relationship exists between obesity and cardiac dysfunction, that obesity cardiomyopathy is an integral component of the clinical manifestations of obesity, and that increased facilitated cardiomyocyte uptake of LCFA is an important mechanism contributing to the pathogenesis of obesity cardiomyopathy.

2. Methods and Procedures

2.1. Mice and Diet

Male C57BL/6J, db/db, and ob/ob mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Me) at 6 wks of age. Upon receipt mice were housed in group cages in a temperature-controlled facility with a 12 h light: dark cycle, with free access to water and to a standard chow diet (LabDiet 5001, PMI, St. Louis, Mo). Starting at 8 weeks of age C57BL/6J mice were divided at random into 2 groups. One group, designated as controls (C), as well as the db/db and ob/ob mice, continued to receive the chow diet. The other C57BL/6J group was fed a high-fat diet (HFD) containing 35% lard (55% of calories from fat; Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ). Weights were recorded weekly. All mice were euthanized at 20 ± 1 wks of age after an overnight (12 hr) fast. All applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of animals were followed during this research. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Columbia University Medical Center.

2.2. Euthanasia and Tissue Harvesting

Euthanasia was accomplished with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine (0.1 mg/g) and xylazine (0.01 mg/g). At sacrifice mice were randomly assigned to either of two protocols. Protocol 1: abdomens were opened, and, after perfusion with “basal” solution [6] via the aorta, hearts were removed for isolation of single cell suspensions of cardiomyocytes. Protocol 2: abdomens were opened as above, and hearts were removed without perfusion and weighed. One portion of each heart was frozen for subsequent biochemical measurements; a second portion was placed in neutral buffered formalin for subsequent paraffin embedding, sectioning, and staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Mallory's trichrome. The remainder was embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, Calif), frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Subsequently, serial 7 μm thick sections were collected on poly-D-lysine-coated slides and stained with oil red O (ORO) and hematoxylin.

2.3. Blood and Serum Analysis

Blood glucose was measured with a glucose meter (One-Touch, LifeScan, Inc., Milpitas, Calif) in preanesthesia tail vein samples. Additional blood was collected from the inferior vena cava at sacrifice and promptly separated by centrifugation. Serum was stored at −20°C for subsequent analysis. The following serum measurements were performed in our laboratory using commercial kits: free fatty acids (FFA, Wako Chemicals USA, Inc, Richmond, Va); triglycerides (L-Type TG H, Wako Chemicals USA); total cholesterol (Cholesterol E, Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan); AST (Stanbio, Boerne, Tex). Leptin and insulin concentrations were determined by immunoassay at the Hormone Research Core Laboratories of Vanderbilt University.

2.4. Determination of Cardiac Tissue Triglyceride and Cholesterol

Protocol 2 heart samples were homogenized in PBS. Total cardiac protein content was determined with the BSA protein analysis kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, Ill), and cardiac triglyceride and cholesterol contents were determined, after Folch extraction [7], with Wako kits (Cholesterol E and L-Type TG H) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.5. Histologic Estimation of Cardiac Neutral Lipids

Histological images of ORO-stained cardiac sections were observed at 250x with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and captured with a Nikon Digital DXM 1200 C camera, using a standard exposure for all photographs. Semiquantitative estimates of neutral lipids in these sections from each mouse were performed by two independent observers (FG, PDB) who were blinded to the experimental protocol, according to the following scale: (−) no positive staining, 0 points; (+) occasional ORO-positive droplets observed by searching in at least 5 high power fields (HPFs), 1 point; (++) small ORO-positive droplets present in most HPFs, 2 points; (+++) obvious, larger ORO-positive droplets in all HPFs, 3 points; (++++) many still larger ORO-positive droplets, sometimes in clumps, in all HPFs, 4 points. An average score for each mouse was calculated from the scores of the two observers. For the 57 samples analyzed for this study the mean difference in lipid scores between the two observers was 0.12 ± 0.04 (SE) points. The slope of the regression line between the two sets of scores was 0.96 (r = 0.94, P < 0.001).

2.6. Transmission Electronic Microscopy

Hearts were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorenson's buffer (0.1 M H2PO4, 0.1 M HPO4, PH 7.2) for at least 12 h. Samples were postfixed with 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M Sorenson's buffer for 1 h. En bloc staining with 1% tannic acid in water was followed by washing and staining with 1% uranyl acetate [8]. Tissues were then embedded in Lx-112 (Ladd Research Industries, Inc, Williston, Vt, USA). Sections of 60 nm were cut on an MT-7000 RMC Ultramicrotome, placed on mesh copper grids (Electron Microscope Sciences, Hatfield, Pa), stained with 1% uranyl acetate and 0.4% lead citrate, and examined under a JEOL JEM-1200 EXII electron microscope.

2.7. Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane until they were unconscious, and 1–1.5% isoflurane was continuously administered thereafter throughout the study. The chest was shaved to minimize ultrasound attenuation. The mouse was then placed on a heated pad with electrocardiographic leads attached to each limb. Echocardiography was performed with Vevo770 (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) instrument, which is designed for use in small animals. B-mode and M-mode two-dimensional (2D) images were obtained in a parasternal short-axis view. Images from these studies were recorded digitally for subsequent analysis. Measurements from the recorded tracings were averaged over at least three cardiac cycles. An experienced operator blinded to the mouse information performed these measurements. In the M-mode short-axis images, anterior and posterior wall thicknesses (AW, PW) and LV end diastolic and systolic dimensions (LVEDD, LVESD) were measured at the midpapillary muscle level. LV percent fractional shortening (%FS), which reflects the change in LV diameter between the contracted and relaxed states, ejection fraction (EF), and LV mass (LVM) were calculated according to Teichholz et al. [9] using B-mode short-axis images at the midpapillary level as

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Equations (2) and (3) incorporate correction factors previously shown to optimize results [9, 10].

2.8. Isolation of Cardiomyocytes

After digestion of heart tissue with collagenase II, mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated as described [11–13], using a protocol which had been shown to yield excellent rat cardiomyocyte preparations [13]. Viability was assessed by trypan blue staining, and only preparations in which ≥80% of cardiomyocytes excluded trypan blue were used. Cells in suspension were counted under a microscope and concentrations adjusted to 1.5 × 106 cells/mL for use in oleic acid (OA) uptake assays.

2.9. Cellular Uptake of Oleic Acid

Using rapid filtration methods well established in our laboratory [14–17], the initial uptake velocity of OA into cardiomyocytes at 37°C from media containing 500 μM BSA was determined in duplicate over 15 sec at five different unbound oleate concentrations. Uptake is linear over this time frame, and we have established that under these conditions measured uptake principally reflects inwardly directed transmembrane long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) transport, relatively independent of either unstirred water layer effects or intracellular binding or metabolism [14–16].

2.10. Computations and Data Fitting

Based on multiple prior studies in both rodents and man [17–22], values for initial oleate uptake velocity at the 5 studied concentrations of unbound oleate were fitted by computer to (4), using SAAM II software as modified for implementation on a lap-top computer [23, 24]. This equation indicates that LCFA uptake is the sum of a saturable plus a nonsaturable function of the unbound LCFA concentration in plasma. Thus,

| (4) |

where Uptake ([OAu]) is the rate of uptake of labeled oleic acid (pmol/sec/50,000 cells) at unbound oleic acid concentration [OAu] (nM), Vmax (pmol/sec/50,000 cells) and Km (nM) are, respectively, the maximal uptake rate of the saturable uptake component and the unbound OA concentration at half-maximal uptake velocity (nM), and k (mL/50,000 cells/sec) is the rate constant for nonsaturable OA uptake. Computed values for physiologic variables are expressed as mean ± S.E.

2.11. Analysis of Heart Gene and Protein Expression

2.11.1. qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cardiac tissue samples using QIAamp RNA Mini Kits (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, Calif) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagent kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif), with random hexamer primers. PCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 50 μL containing 500 ng cDNA on the 7300 Real-Time PCR system using SYBR GREEN PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) as detailed in the manufacturer's guidelines. We used geNormTM kit β2M (beta-2-microglobulin), GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase), UBC (ubiquitin C) (PrimerDesign Ltd, UK), and 18sRNA (IDT, San Jose, Calif) for housekeeping gene analysis. Primer sequences were selected with the use of Primer 3 software (S. Rozen, H. Skaletsky http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). We used Got2 (glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 2, mitochondrial), Slc27a1 (long-chain fatty acid transport protein 1), Slc27a6 (long-chain fatty acid transport protein 6), Cd36 (fatty acid translocase), and Scd1 (stearoyl CoA desaturase-1) and Fasn (fatty acid synthase) primers (IDT, San Jose, Calif) to quantitate the expression levels of these genes. We also used Ndufaf4 (NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, assembly factor 4), Ndufa8 (NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 8), Sdhd (succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit D, integral membrane protein), Cox5b (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit Vb), Cox6b1 (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb polypeptide 1), Cox6c (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIc), Uqcrc2 (ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase core protein 2), Uqcrfs1 (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, Rieske iron-sulfur polypeptide 1), and Atp5j (ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit F) and Atp5h (ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F0 complex, subunit d) primers to quantitate oxidative phosphorylation-associated gene expression and a primer to examine expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α).

2.11.2. Western Blots

For detection of CD36 and fatty acid transport protein 1 (FATP1), total protein extracts were prepared from murine heart with use of cell lysis buffer (RIPA Buffer, Teknova). Particulate material was removed by centrifugation, and protein concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit. Equal amounts of total protein (50 μg/sample) were subjected to electrophoresis in NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif) and then electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation of membranes with nonfat dry milk (5%) for at least 1 h at room temperature. The blots were incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-mouse FATP1 (Santa Cruz, Calif) or goat anti-mouse CD36 (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn). Each primary antibody was incubated for 2 h or overnight at a dilution of 1 : 500. Goat anti-rabbit and donkey anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies (1 : 1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to identify primary antibody binding sites. All the Western blot results were analyzed by scanning densitometry and densitometric image analyzer software (Image J, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/download/)).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean ± SE. Single comparisons were examined with Student's t-tests, with statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05. For the parameters reported in Tables 1 and 2, each of the three experimental groups was compared to the control group (principal goal, three comparisons); the three experimental groups were also compared with each other (secondary goal, three more comparisons). Statistical significance was again set at P ≤ 0.05. Analysis was by one way ANOVA, followed by post hoc t-tests, using the pooled standard deviation in computing standard errors of group differences. Application of the Bonferroni correction would have required setting the limit of significance at P ≤ 0.008 (0.05 divided by 6, the number of intergroup comparisons). This was unachievable given the numbers of animals per group. We have therefore simply reported the P values for these post hoc tests in the legends of Tables 1 and 2. Any P value that is below the Bonferroni-corrected value of 0.0083 can be taken as definitively significant, whereas other P values (0.05 > P > 0.0083) can be considered only as exploratory or suggestive.

Table 1.

Heart weights and lipid content. Heart weights and cardiac triglyceride and cholesterol content were measured. Data reported as mean ± SE. Results of ANOVA, followed by post hoc t-tests.

| Group | Heart weight (g) | Heart triglycerides (mg) | Heart cholesterol (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 30) | 0.125 ± 0.002 | 0.68 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.07 |

| HFD (n = 19) | 0.145 ± 0.006** | 1.40 ± 0.22∗‡ | 0.54 ± 0.16 |

| db/db (n = 7) | 0.143 ± 0.002* | 2.73 ± 0.32** | 3.71 ± 1.06** |

| ob/ob (n = 22) | 0.157 ± 0.006** | 2.87 ± 0.35∗∗§§ | 5.89 ± 1.99∗∗§ |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control group. ‡P < 0.01 (HFD versus db/db); §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01 (HFD versus ob/ob).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic results. Anterior wall thickness, posterior wall thickness, left ventricular end diastolic dimension, left ventricular end systolic dimension, left ventricular mass, ejection fraction, and fractional shortening were measured. Data reported as mean ± SE. Results of ANOVA, followed by post hoc t-tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control group; †P < 0.05, ‡P < 0.01 (HFD versus db/db); §P < 0.05, §§P < 0.01 (HFD versus ob/ob); £P < 0.05, P < 0.01 (db/db versus ob/ob).

| Groups | Heart rate | AW (mm) | PW (mm) | LVEDD (mm) | LVESD (mm) | LVM (mg) | EF (%) | FS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 456 ± 13 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.72 ± 0.02 | 4.03 ± 0.08 | 2.50 ± 0.08 | 85.25 ± 3.17 | 61.52 ± 1.38 | 38.05 ± 1.08 |

| HFD | 474 ± 12 | 0.80 ± 0.01∗∗‡ | 0.77 ± 0.02‡ | 4.23 ± 0.08‡ | 2.80 ± 0.05** | 101.89 ± 4.86** | 55.95 ± 0.73∗∗† | 33.62 ± 0.55∗∗† |

| db/db | 445 ± 4 | 0.88 ± 0.03** | 0.86 ± 0.02** | 3.89 ± 0.08£ | 2.70 ± 0.09 | 101.74 ± 4.6** | 51.76 ± 1.79** | 30.66 ± 1.29** |

| ob/ob | 458 ± 9 | 0.87 ± 0.03∗∗§ | 0.85 ± 0.02∗∗§§ | 4.16 ± 0.09 | 2.93 ± 0.09** | 112.19 ± 1.0** | 50.53 ± 1.4∗∗§§ | 29.70 ± 1.00∗∗§§ |

AW: anterior wall thickness.

PW: posterior wall thickness.

LVEDD: left ventricular end diastolic dimension.

LVESD: left ventricular end systolic dimension.

LVM: left ventricular mass.

%EF: percent ejection fraction.

%FS: percent fractional shortening.

3. Results

3.1. Age, Body Weight, and Serum Biochemical Tests

The mean age of the studied mice was 139 ± 1 days and was equivalent in all four groups. HFD-fed (37.95 ± 1.11 g, n = 19), db/db (51.78 ± 0.57 g, n = 7), and ob/ob (62.5 ± 0.53 g, n = 22) mice, collectively designated the obesity groups, were all significantly heavier than chow-fed C57BL/6J controls (26.58 ± 0.24 g, n = 30). Values for blood glucose, HOMA-IR and serum insulin, leptin, total fatty acids, triglycerides, cholesterol, and AST values will be found in a prior publication dealing with the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis in these same animals [5]. Briefly, blood glucose was significantly increased only in the HFD group, serum insulin in the db/db and ob/ob groups, and serum leptin in the HFD and db/db groups, but the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), calculated as previously described in mice [25], was significantly increased in all obesity groups. Serum cholesterol was also elevated in all three obesity groups, but triglycerides were increased only in the HFD and ob/ob animals. Although the total LCFA concentration was somewhat greater in all experimental groups than in controls, in none of the groups was the increase statistically significant. However, in contrast to total LCFA, the increase in unbound LCFA (LCFAu), which provides the driving force for LCFA uptake, was statistically significant in all experimental groups [5]. Serum AST was significantly increased in db/db and ob/ob but not HFD mice.

3.2. Heart Weights and Triglyceride Content

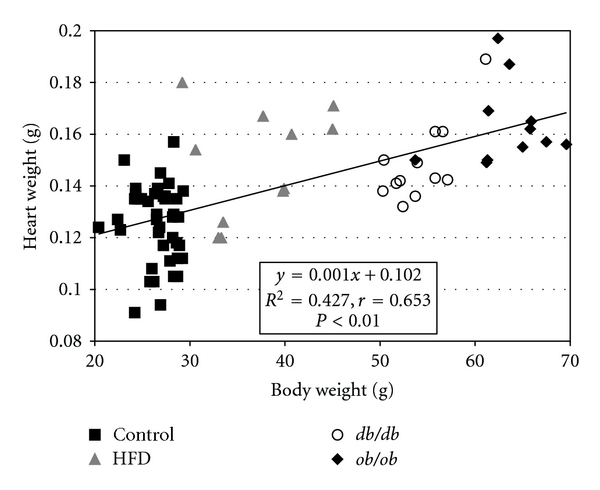

Heart weights and triglyceride content were increased in all obesity groups; heart cholesterol content was increased in ob/ob and db/db but not HFD animals (Table 1). Heart weights (Figure 1: r = 0.65), cardiac triglyceride content (r = 0.80), and cardiac cholesterol content (r = 0.62) were all significantly correlated with body weight (P < 0.01 in each instance).

Figure 1.

Heart weights were significantly correlated with body weight across the four experimental groups (P < 0.01).

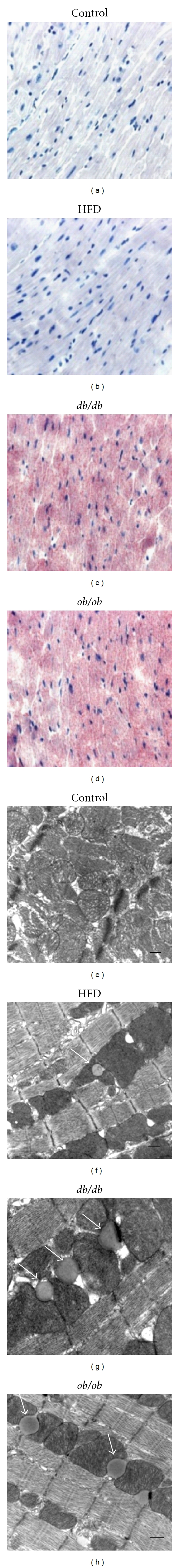

3.3. Cardiac Histologic Analysis by Oil Red O Staining and Transmission Electron Microscopy

ORO-positive lipid droplets were rare in control cardiomyocytes (Figure 2(a)). Despite a significant increase in biochemical measurements of TG in the HFD group, only occasional ORO-positive lipid droplets were observed by light microscopy in HFD myocardial cells (Figure 2(b)), but marked lipid accumulation was seen in db/db and ob/ob mice (Figures 2(c) and 2(d)). In transmission electron microscopic images, lipid droplets were seen in the hearts of HFD animals, but lipid droplets were both larger and more abundant in db/db and ob/ob mice (Figures 2(e), 2(f), 2(g), and 2(h)). Semiquantitative grading of ORO-stained cardiac sections did not show appreciable differences in the average grade of lipid deposition between HFD (0.54 ± 0.14) and control (0.6 ± 0.13) mice; however, in db/db (2.4 ± 0.38) and ob/ob (3.4 ± 0.14) groups, the grade of lipid deposition was, respectively, 4 times and 6 times higher than in the C and HFD groups (P < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Cardiac histology. ((a), (b), (c), and (d)). Representative Oil-Red-O-(ORO-) stained sections of hearts from (a) control, (b) high fat diet-fed (HFD), (c) db/db, and (d) ob/ob mice. Lipid droplets were rare in control hearts and uncommon in HFD mice despite a ~12-fold increase in cardiac triglyceride content in the latter group. There was an obvious increase in ORO-stainable lipid in the hearts of ob/ob and db/db mice. ((e), (f), (g), and (h)). Transmission electron microscope images of (e) control, (f) HFD, (g) db/db, and (h) ob/ob mice. Lipid droplets (arrows) were rare in control hearts, but individual droplets could be found in many fields in the HFD group. Lipid droplets were larger and much more common in db/db and ob/ob hearts, with multiple droplets typically being observed in most fields. The scale bar indicates 500 nm. Lipid droplets in the heart were almost uniformly in direct contact with mitochondria.

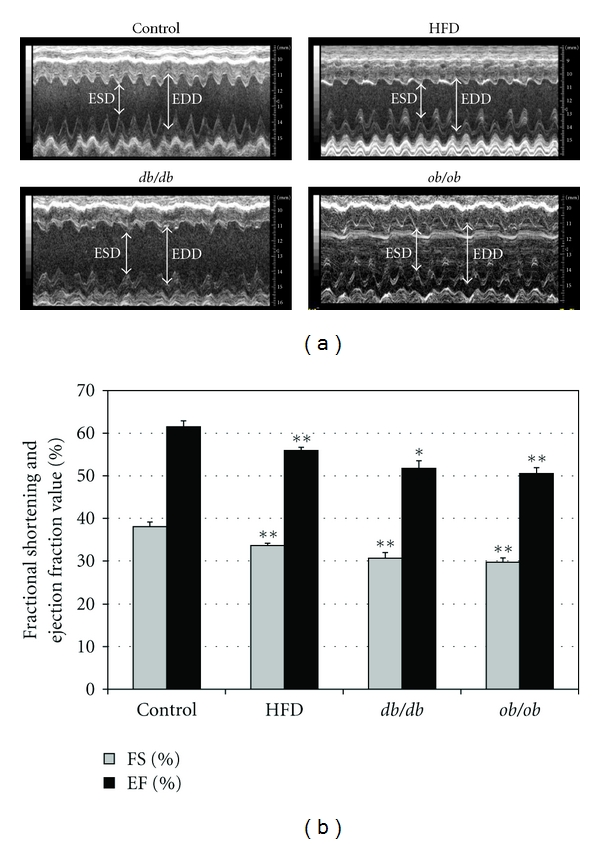

3.4. Cardiac Function Analysis by 2D Echocardiography

By echocardiographic measurement, both AW and PW were increased in the obesity group mice (Table 2). Echocardiographic estimates of left ventricular mass were also increased in HFD (101.89 ± 4.86 mg), db/db (101.74 ± 4.6 mg), and ob/ob mice (112.20 ± 1.0 mg) compared to C (85.25 ± 3.17 mg) and were highly correlated with tissue measurements of total heart weight (r = 0.98, P < 0.01). The end systolic diameter (LVESD) averaged 2.50 ± 0.08 mm and the end diastolic diameter (LVEDD) 4.03 ± 0.08 mm in control mice. Although the average LVESD was increased in the obesity groups, the LVEDD was similar in all groups (Table 2, Figure 3(a)), so that the obesity groups did not meet the basic criteria for a dilated cardiomyopathy. Percent FS, which was 38 ± 1.1% in C, decreased to 33 ± 0.6% in HFD, 30 ± 1.3% in db/db, and 29 ± 1.0% in ob/ob mice (P < 0.01 versus control for each group) (Figure 3(b)). Similarly, EF decreased in HFD (56 ± 0.7%), db/db (52 ± 1.8%), and ob/ob mice (51 ± 1.4%) compared to C (62 ± 1.4%) (P < 0.01 versus control for each group) (Figure 3(b)). EF was negatively correlated with body weight (r = −0.70, P < 0.01) and cardiac TG (r = −0.83, P < 0.01) across the four groups studied (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cardiac function was assessed by echocardiography. (a) M-mode image of the left ventricle in the parasternal short-axis view, showing depth markers. EDD: left ventricular end-diastolic diameter. ESD: left ventricular end-systolic diameter. (b) Fractional shortening of the diameter of the left ventricle between the contracted and relaxed states and ejection fraction were calculated from echocardiographic measurements made during the cardiac cycle. Ejection fraction (EF) is the fraction of the end-diastolic volume that is ejected with each beat; that is, it is stroke volume (SV), divided by end-diastolic volume (EDV). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control group.

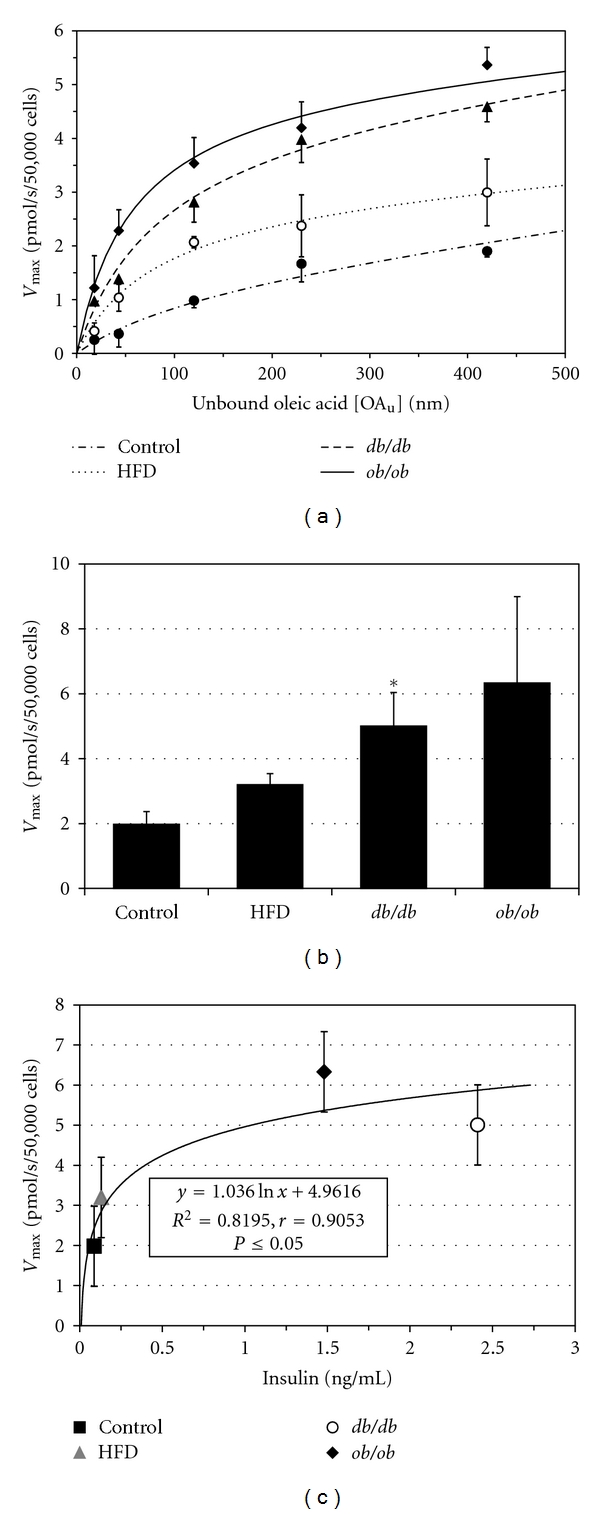

3.5. LCFA Uptake Studies

As previously reported in adipocytes [17] and hepatocytes [5, 26], uptake of [3H]-oleic acid by isolated mouse cardiomyocytes consisted of the sum of a saturable plus a nonsaturable component. In all groups studied, the saturable component predominated over the physiologic range of unbound oleic acid concentrations. Typical uptake curves in control, HFD, db/db, and ob/ob cardiomyocytes are shown in Figure 4(a). Saturable cardiomyocyte LCFA uptake, reflected in an increased Vmax, was increased in each of the obesity groups (Figure 4(b)). The mean Vmax in HFD, db/db, and ob/ob mice was 1.4, 2.0, and 3.2 times that in control mice. The increases were only significant in the db/db mice (P < 0.05), but not in the ob/ob animals, which had the greatest mean increase, due to greater scatter in the data. There was a significant nonlinear correlation between Vmax and serum insulin in the groups (r = 0.91, Figure 4(c)), consistent with increasing levels of insulin resistance in the obesity group animals.

Figure 4.

(a) [3H]-oleic acid uptake curves for cardiomyocytes from control, HFD, db/db, and ob/ob mice. Data points are mean ± SE. (b) Vmax for saturable cardiomyocyte LCFA uptake is increased in all obesity groups compared with the control group. Bars represent mean ± 1 SE. *indicates P < 0.05 compared to controls. (c) Relationship between serum insulin concentration and [3H]-oleic acid uptake Vmax, indicating a significant nonlinear correlation which may reflect, in part, insulin resistance.

3.6. Gene and Protein Expression

3.6.1. Genes Involved in LCFA Uptake

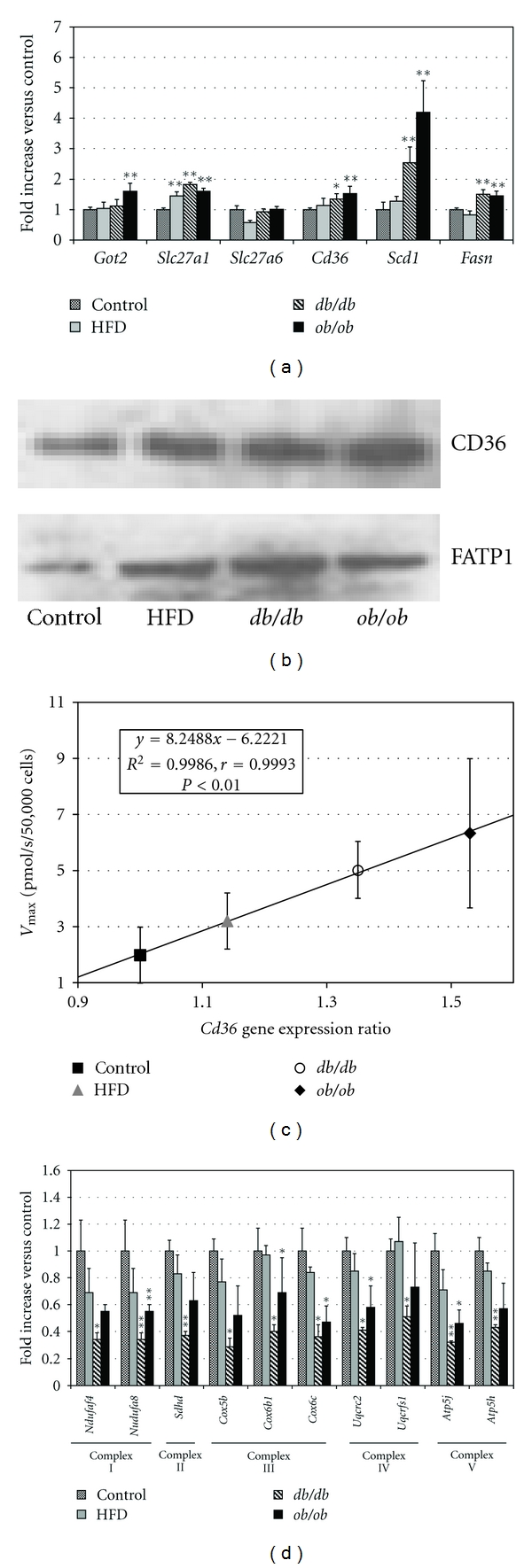

Gene expression ratios for the cardiac LCFA transporters, Got2, Slc27a1, Slc27a6, and Cd36, and of critical enzymes involved in de novo LCFA synthesis, Scd1 and Fasn, are shown in Figure 5(a). Got2, encoding the transporter FABPpm/mAsp-AT, was upregulated only in ob/ob mice; Slc27a1, which encodes FATP1, was significantly upregulated in all three of the obesity groups; Cd36, encoding CD36/FAT, was significantly upregulated in both ob/ob and db/db animals. Our Western blot analysis confirmed that both CD36 and FATP1 were upregulated in the obesity groups (Figure 5(b)). The expression ratio for Cd36, in particular, was highly correlated with the [3H]-oleic acid uptake Vmax in all of the obesity groups, with an r = 0.99 (P < 0.01) for the gene expression data (Figure 5(c)) and r = 0.93 for the protein expression (Western blot) results. There was a lesser degree of correlation between Vmax and the Slc27a1 expression ratio (r = 0.65, data not shown). By contrast, Slc27a6, which encodes the putative cardiac transporter FATP6, was not upregulated in cardiomyocytes from any of the obesity groups.

Figure 5.

(a) Cardiac gene expression ratios for cardiac LCFA transporters (Got2, Slc27a1, Slc27a6, and Cd36) and for two enzymes of LCFA synthesis, stearoyl CoA desaturase-1 (Scd1), and fatty acid synthase (Fasn). Fasn and Scd1 were significantly upregulated in ob/ob and db/db mice. (b) Representative Western blots of expression of CD36 and FATP1 in control, HFD, db/db, and ob/ob mice. (c) Vmax for [3H]-oleic acid uptake in cardiomyocytes is significantly correlated with the Cd36 gene expression ratio in all obesity groups. (d) Cardiac expression ratios of 10 oxidative phosphorylation genes. Complex I: NADH dehydrogenase (Ndufaf4, Ndufa8); complex II: fumarate reductase (Sdhd); complex III: cytochrome c reductase (Cox5b, Cox6b1, and Cox6c); complex IV: cytochrome c oxidase (Uqcrc2, Uqcrfs1); Complex V: F-type ATPase (Atp5j, Atp5h) were all downregulated in all obesity groups. Error bars indicate ± 1 SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with the control group.

While not a transporter per se, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) can increase LCFA uptake by hydrolyzing the triglycerides of circulating lipoproteins, making their component LCFA available for facilitated uptake [27]. We found the LPL expression ratio to be significantly elevated (P < 0.01) in db/db (1.78 ± 0.05) and ob/ob (1.72 ± 0.1) but not HFD (1.07 ± 0.07) animals. Local LCFA concentrations in myocardial capillaries in the former strains may therefore be higher than those we measured in bulk plasma, with correspondingly greater absolute rates of facilitated LCFA uptake, but the extent of this local increase in LCFA concentrations cannot be directly measured.

3.6.2. Genes for De Novo LCFA Synthesis

Fasn, encoding fatty acid synthase, and Scd1, which encodes stearoyl Co-A desaturase 1, were both significantly upregulated in db/db and ob/ob mice. A small increase in Scd1 in HFD animals did not reach statistical significance.

3.6.3. Oxidative Phosphorylation and ATP Synthesis

Based on the results of gene expression microarray studies in obese human fat [28], we assayed in mouse cardiomyocytes the expression of 10 genes in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomics (KEGG) Oxidative Phosphorylation pathway [29] that are components of the four mitochondrial electron transport and the ATP synthase complexes. Ndufaf4 and Ndufa8 (complex I, NADH dehydrogenase); Sdhd (complex II, fumarate reductase); Cox5b, Cox6b1, and Cox6c (complex III, cytochrome c reductase); Uqcrc2 and Uqcrfs1 (complex IV, cytochrome c oxidase); Atp5j and Atp5h (complex V, F-type ATPase) were all downregulated to approximately the same extent in all three obesity groups (Figure 5(d)). Genes within these complexes have been reported to be downregulated in several tissues in both man [28] and experimental animals in association with obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance [30–34]. In preliminary studies, expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated-receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) was downregulated by 40% in ob/ob and 39% in db/db animals.

4. Discussion

Arteriosclerotic ischemic heart disease is a major consequence of obesity [1]. Less widely appreciated, although it was first discovered by Harvey nearly 400 years ago [35], it is an apparently nonarteriosclerotic cardiomyopathy designated cor adiposum, or fatty heart, which is again being increasingly recognized in severely obese patients [36–39]. As already noted, cardiac complications of obesity are particularly prevalent in patients with NAFLD [3, 4], a phenomenon that may be explained in part by the high degree of correlation (r = 0.81, P < 0.01) observed between the cardiac triglyceride content reported in the present study and the previously reported hepatic triglyceride content in the same animals [5]. The average body weights of our HFD-fed, db/db, and ob/ob mice were 1.3, 1.9 and 2.3 times those of control animals, corresponding very roughly in human terms to obesity, morbid obesity, and super obesity, respectively, and all had hepatic steatosis. The elevations in blood glucose and serum FFA and TG seen in these obese mice parallel what is observed in comparably obese humans. Each mouse group studied also had significant ectopic myocardial lipid accumulation and a corresponding decrease in LV contractility, suggesting that they might be models for human obesity cardiomyopathy. Lipid-associated cardiomyopathies in mutant and transgenic mice [40–43] further stimulated us to examine the hearts of mice on whose livers we had initially focused.

We have compared basic pathophysiologic features of three widely studied mouse models of obesity corresponding values in normal control animals. In db/db and ob/ob animals defective leptin signaling is the fundamental cause of the obesity [44]. In contrast, in C57BL/6J mice fed a HFD, leptin signaling is initially normal. The pathogenetic diversity of the models studied suggests that the observations made can, at least tentatively, be considered representative of the obese state in general. While cardiac function has been studied in ob/ob, db/db, and HFD-fed mice separately, we believe this to be the first study directly comparing them.

Our studies show that an increase in total body weight due to any of several different mechanisms is significantly correlated with an increase in both heart weight and cardiac TG content. These data parallel findings in man [39]. As with hepatic steatosis [45–47], increased myocardial TG content can result from one or more of several processes that increase cardiomyocyte LCFA or TG uptake or synthesis or decrease LCFA metabolism or TG export. In contrast to our findings in the liver, in which facilitated LCFA uptake was increased only in obesity models with normal leptin signaling, the Vmax for saturable LCFA uptake is upregulated in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes from all Obesity Groups.

We examined the associations between reduced cardiac function and body weight, cardiac TG content, LCFA uptake Vmax and serum levels of LCFA and triglycerides by linear regression. Reductions in ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening of the left ventricle during systole (%FS) were strongly negatively correlated with body weight (r = −0.98), cardiac TG content (r = −0.98), and LCFA uptake Vmax (r = −0.97) across all of the Obesity Groups. These correlations were significantly stronger than those between cardiac function and serum levels of either LCFA (r = −0.79) or TG (r = −0.62). Our studies were not specifically designed to identify the individual contributions of the many components of the obese phenotype to the observed reductions in cardiac function. However, these results do not suggest that either increased circulating levels of fatty acids or hypertriglyceridemia is as important as obesity per se or obesity-associated increases in cardiac LCFA uptake and triglyceride accumulation.

Our technique for studying cellular LCFA uptake, in which measurements are made over 15–30 sec, is unique in determining unidirectional, facilitated influx rates, largely independent of intracellular binding and metabolism [14]. In specific settings results obtained by this approach have been shown to be highly correlated with the expression of specific LCFAs transporters [5, 19]. Alternative approaches, in which labeled LCFA are injected intravenously into living animals and hepatic LCFA content determined minutes later, reflect a much more complex process which, in addition to cellular influx, is influenced by changes in blood flow, intracellular binding, efflux, esterification, oxidation, and possibly other processes, each subject to its own genetic regulation. The two approaches generally, but not always, yield similar results.

Four proteins have been proposed as important cardiac LCFA transporters: CD36, also known as fatty acid translocase or FAT, plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein (FABPpm), which has proven identical to mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (mAspAT), and fatty acid transport proteins 1 and 6 (FATP1 and FATP6). In the present study, when assayed by both qPCR and Western blot, upregulation of the Cd36 (CD36) and Slc27a1 (FATP1) genes and proteins was found in the HFD, db/db, and ob/ob groups, confirming that CD36 and FATP1 play an important role in cardiomyocyte lipid accumulation. The gene for FABPpm/mAspAT (Got2) was upregulated in ob/ob mice. Upregulation of the Slc27a6 gene was not observed in any of the groups. Expression ratios for Cd36 were especially highly correlated with Vmax across all of the obesity groups. In addition to transporters, upregulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (Scd1) gene was observed in all the obesity groups; fatty acid synthase (Fasn) was significantly upregulated in both db/db and ob/ob mice, suggesting that, as in the liver, increased de novo LCFA synthesis may contribute to the increased cardiomyocyte triglyceride levels in these animals.

Numerous prior publications indicate that obesity can influence the structure and function of the heart in mouse, rat, and man [48–56]. An association of local lipid accumulation and cardiac dysfunction was reported in early human studies [48] and has been meticulously confirmed [57]. Left ventricular hypertrophy and decreased contractility, typical features of the cardiomyopathy of human obesity [48], were also the pattern consistently observed in the present mouse studies. The relationship between myocardial lipids and cardiac function was established conclusively by Chiu et al. [41], who created a line of transgenic mice selectively overexpressing myocardial long-chain acylCoA synthetase (ACAS). By esterifying LCFA after initial uptake into cardiac myocytes, thereby preventing their otherwise rapid passive efflux, overexpression of this enzyme has the effect of trapping LCFA within these cells, where their subsequent metabolism leads to accumulation of toxic lipid species. This is initially associated with cardiac hypertrophy, followed by left ventricular dysfunction and early death. A second transgenic line that overexpresses the myocardial LCFA transporter FATP1 has a similar, but not identical, cardiomyopathy [43].

Generation of reactive oxygen species from increased LCFA oxidation and mitochondrial injury have been considered important pathogenetic processes in the development of both lipid- and alcohol-associated cardiomyopathies. Epicardial fat has a rapid lipolytic rate. Since the heart is immediately downstream of its visceral (extra- and intrapericardial) fat depots and has a first-pass relationship with respect to any LCFAs released from them [52], this results in increased cardiac delivery and uptake of LCFA, which would tend to become virtually continuous with the onset of antilipolytic insulin resistance. Therefore, it is not surprising that obesity in many settings is associated with changes in cardiomyocyte morphology, mitochondrial number, and contractile function. Increased mitochondrial number has been described, for example, in the hearts of ob/ob [52, 54] and db/db mice [58]. There is also accumulating evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction. Based on these data it has been suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired myocardial energetics may contribute to contractile dysfunction in the hearts of these mice and of obese patients, increasing their susceptibility to heart failure [55, 59]. Our demonstration of coordinated down-regulation of 10 genes involved in the cardiac mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis pathway in all three obesity models studied is entirely consistent with this hypothesis.

Our data provide strong evidence that upregulation of facilitated LCFA uptake is an important mechanism contributing to increased myocardial lipid accumulation across a spectrum of mouse models of obesity. The data also point to CD36 and FATP1 as the transporters principally responsible for the increase in LCFA uptake. The contribution of increased de novo LCFA synthesis, suggested by qRT-PCR studies of the expression of relevant genes, requires further functional confirmation. Finally, the coordinate down-regulation of 10 genes in the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation/ATP synthesis pathway suggested down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a key regulator of cardiac mitochondrial functions including mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, ATP synthesis, and lipid homeostasis [59–61]. Preliminary observations reported above strongly suggest that PGC-1α is indeed downregulated in at least some models of obesity. We postulate that PGC-1α-mediated decreased ATP synthesis will prove to be responsible for the reductions in %FS and EF observed in these models.

In this study we have established a clear relationship between obesity, increased cardiac triglyceride content, and cardiac dysfunction in mice with a spectrum of causes for obesity. This suggests that cardiomyopathy, rather than being a novelty, is an integral part of the spectrum of obesity-related disorders. We have also established that increased facilitated transport of LCFA into the cardiomyocyte is an important pathogenic mechanism in this process. We have also identified other genes of interest, future studies of which may explain many of these findings. These include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), a master regulator of lipid and energy metabolism, as well as those involved in ATP synthesis. Despite these data, the precise processes by which cardiomyocyte lipid accumulation leads to myocardial dysfunction remain to be elucidated. Whether they are the same as those described as “lipotoxic cardiomyopathy” in transgenic mouse models [41, 43] is unclear. Nevertheless, the many similarities between the present cardiac findings in mice and analogous human data suggest that these mice may be useful models for human obesity cardiomyopathy, particularly given the limitations in obtaining human cardiac tissue for study. Moreover, the correlations we observed between body weight, myocardial lipid accumulation, and decreased LV function, over a weight spectrum ranging from normal to super obesity, suggest that the recent observations of myocardial dysfunction in severely obese patients may be the tip of a much larger iceberg.

Contribution

The contributions of Dr. Ge and Dr. Hu to this study were equivalent.

Conflict of Interests

None of the authors has any conflict of interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by Grants DK-52401 and DK0772526-S1 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank K. R. Brown (Department of Pathology) for the transmission electron microscope photomicrographs, the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Histology Core for preparing the frozen sections and Oil Red O staining and Dr. Rajasekhar Ramakrishnan for biostatistical advice.

References

- 1.Bray GA. Medical consequences of obesity. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89(6):2583–2589. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abel ED, Litwin SE, Sweeney G. Cardiac remodeling in obesity. Physiological Reviews. 2008;88(2):389–419. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Mathiesen UL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with NAFLD and elevated liver enzymes. Hepatology. 2006;44(4):865–873. doi: 10.1002/hep.21327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schindhelm RK, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, et al. Alanine aminotransferase and the 6-year risk of the metabolic syndrome in Caucasian men and women: the Hoorn Study. Diabetic Medicine. 2007;24(4):430–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge F, Zhou S, Hu C, Lobdell H, Berk PD. Insulin- and leptin-regulated fatty acid uptake plays a key causal role in hepatic steatosis in mice with intact leptin signaling but not in ob/ob or db/db mice. American Journal of Physiology. 2010;299(4):G855–G866. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Protas L, Barbuti A, Qu J, et al. Neuropeptide Y is an essential in vivo developmental regulator of cardiac ICa,L. Circulation Research. 2003;93(10):972–979. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000099244.01926.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1957;226(1):497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayat MA. Principles and Techniques of Electron Microscopy. 3rd edition. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic angiographic correlations in the presence or absence of asynergy. American Journal of Cardiology. 1976;37(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J, Bu L, Gong H, et al. Effects of heart rate and anesthetic timing on high-resolution echocardiographic assessment under isoflurane anesthesia in mice. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2010;29(12):1771–1778. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.12.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittenberg BA, Robinson TF. Oxygen requirements, morphology, cell coat and membrane permeability of calcium-tolerant myocytes from hearts of adult rats. Cell and Tissue Research. 1981;216(2):231–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00233618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewett K, Legato MJ, Danilo P, Robinson RB. Isolated myocytes from adult canine left ventricle: Ca2+ tolerance, electrophysiology, and ultrastructure. The American journal of physiology. 1983;245(5):H830–H839. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.5.H830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorrentino D, Stump D, Potter BJ, et al. Oleate uptake by cardiac myocytes is carrier mediated and involves a 40-kD plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein similar to that in liver, adipose tissue, and gut. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1988;82(3):928–935. doi: 10.1172/JCI113700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stremmel W, Berk PD. Hepatocellular influx of [14C]oleate reflects membrane transport rather than intracellular metabolism or binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(10):3086–3090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stremmel W, Strohmeyer G, Berk PD. Hepatocellular uptake of oleate is energy dependent, sodium linked, and inhibited by an antibody to a hepatocyte plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(11):3584–3588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorrentino D, Robinson RB, Kiang CL, Berk PD. At physiologic albumin/oleate concentrations oleate uptake by isolated hepatocytes, cardiac myocytes, and adipocytes is a saturable function of the unbound oleate concentration. Uptake kinetics are consistent with the conventional theory. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1989;84(4):1325–1333. doi: 10.1172/JCI114301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stump DD, Fan X, Berk PD. Oleic acid uptake and binding by rat adipocytes define dual pathways for cellular fatty acid uptake. Journal of Lipid Research. 2001;42(4):509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berk PD, Stump DD. Mechanisms of cellular uptake of long chain free fatty acids. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1999;192(1-2):17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berk PD, Zhou SL, Kiang CL, Stump D, Bradbury M, Isola LM. Uptake of long chain free fatty acids is selectively up-regulated in adipocytes of zucker rats with genetic obesity and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(13):8830–8835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berk PD, Zhou SL, Kiang CL, Stump DD, Fan X, Bradbury MW. Selective up-regulation of fatty acid uptake by adipocytes characterizes both genetic and diet-induced obesity in rodents. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(40):28626–28631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berk PD, Zhou S, Bradbury MW. Increased hepatocellular uptake of long chain fatty acids occurs by different mechanisms in fatty livers due to obesity or excess ethanol use, contributing to development of steatohepatitis in both settings. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2005;116:335–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrescu O, Fan X, Gentileschi P, et al. Long-chain fatty acid uptake is upregulated in omental adipocytes from patients undergoing bariatric surgery for obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2005;29(2):196–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman M, Weiss MF. User’s Manual for SAAM U.S. Public Health Service Publication 1703. Washington, DC, USA: Department of Health and Human Services; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAAMII User Guide. Seatle, Wash, USA: SAAM Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akagiri S, Naito Y, Ichikawa H, et al. A mouse model of metabolic syndrome; Increase in visceral adipose tissue precedes the development of fatty liver and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed male KK/Ta mice. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2008;42(2):150–157. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.2008022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stump DD, Nunes RM, Sorrentino D, Isola LM, Berk PD. Characteristics of oleate binding to liver plasma membranes and its uptake by isolated hepatocytes. Journal of Hepatology. 1992;16(3):304–315. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg IJ, Eckel RH, Abumrad NA. Regulation of fatty acid uptake into tissues: lipoprotein lipase- and CD36-mediated pathways. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50:S86–S90. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800085-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walewski JL, Ge F, Gagner M, et al. Adipocyte accumulation of long-chain fatty acids in obesity is multifactorial, resulting from increased fatty acid uptake and decreased activity of genes involved in fat utilization. Obesity Surgery. 2010;20(1):93–107. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0002-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsueh WC, Mitchell BD, Schneider JL, et al. Genome-wide scan of obesity in the old order Amish. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;86(3):1199–1205. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Rich SS, et al. A genome scan for ESRD in black families enriched for nondiabetic nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2004;15(10):2719–2727. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000141312.39483.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustelin L, Pietiläinen KH, Rissanen A, et al. Acquired obesity and poor physical fitness impair expression of genes of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in monozygotic twins discordant for obesity. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(1):E148–E154. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00580.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(14):8466–8471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032913100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nature Genetics. 2003;34(3):267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harvey W. Works of William Harvey. London, UK: Sydenham Society; 1628. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zalesin KC, Franklin BA, Miller WM, Peterson ED, McCullough PA. Impact of obesity on cardiovascular disease. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2008;37(3):663–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong C, Marwick TH. Obesity cardiomyopathy: pathogenesis and pathophysiology. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2007;4(8):436–443. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong C, Marwick TH. Obesity cardiomyopathy: diagnosis and therapeutic implications. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2007;4(9):480–490. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGavock JM, Victor RG, Unger RH, Szczepaniak LS. Adiposity of the heart, revisited. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144(7):517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belke DD, Larsen TS, Gibbs EM, Severson DL. Altered metabolism causes cardiac dysfunction in perfused hearts from diabetic (db/db) mice. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;279(5):E1104–E1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Ford DA, et al. A novel mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001;107(7):813–822. doi: 10.1172/JCI10947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Sambandam N, Han X, et al. CD36 deficiency rescues lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2007;100(8):1208–1217. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264104.25265.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Blanton RM, et al. Transgenic expression of fatty acid transport protein 1 in the heart causes lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2005;96(2):225–233. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154079.20681.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myers MG, Cowley MA, Münzberg H. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance. Annual Review of Physiology. 2008;70:537–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldberg IJ, Ginsberg HN. Ins and outs modulating hepatic triglyceride and development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4):1343–1346. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verna EC, Berk PD. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of obesity and fatty liver: impact of bariatric surgery. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2008;28(4):407–426. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berk PD. Regulatable fatty acid transport mechanisms are central to the pathophysiology of obesity, fatty liver, and metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2008;48(5):1362–1376. doi: 10.1002/hep.22632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasper EK, Hruban RH, Baughman KL. Cardiomyopathy of obesity: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 43 obese patients with heart failure. American Journal of Cardiology. 1992;70(9):921–924. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90739-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perseghin G, Lattuada G, De Cobelli F, et al. Increased mediastinal fat and impaired left ventricular energy metabolism in young men with newly found fatty liver. Hepatology. 2008;47(1):51–58. doi: 10.1002/hep.21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kankaanpää M, Lehto H-R, Pärkkä JP, et al. Myocardial triglyceride content and epicardial fat mass in human obesity: relationship to left ventricular function and serum free fatty acid levels. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006;91(11):4689–4695. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bugianesi E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and cardiac lipotoxicity: another piece of the puzzle. Hepatology. 2008;47(1):2–4. doi: 10.1002/hep.22105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boudina S, Abel ED. Mitochondrial uncoupling: a key contributor to reduced cardiac efficiency in diabetes. Physiology. 2006;21(4):250–258. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00008.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong F, Zhang X, Yang X, et al. Impaired cardiac contractile function in ventricular myocytes from leptin-deficient ob/ob obese mice. Journal of Endocrinology. 2006;188(1):25–36. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boudina S, Sena S, Theobald H, et al. Mitochondrial energetics in the heart in obesity-related diabetes: direct evidence for increased uncoupled respiration and activation of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes. 2007;56(10):2457–2466. doi: 10.2337/db07-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neubauer S. The failing heart—an engine out of fuel. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356(11):1140–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park SY, Cho YR, Kim HJ, et al. Unraveling the temporal pattern of diet-induced insulin resistance in individual organs and cardiac dysfunction in C57BL/6 mice. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3530–3540. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marfella R, Di Filippo C, Portoghese M, et al. Myocardial lipid accumulation in patients with pressure-overloaded heart and metabolic syndrome. Journal of Lipid Research. 2009;50(11):2314–2323. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P900032-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barouch LA, Gao D, Chen L, et al. Cardiac myocyte apoptosis is associated with increased DNA damage and decreased survival in murine models of obesity. Circulation Research. 2006;98(1):119–124. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000199348.10580.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms for myocardial mitochondrial dysfunction in the metabolic syndrome. Clinical Science. 2008;114(3-4):195–210. doi: 10.1042/CS20070166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sihag S, Cresci S, Li AY, Sucharov CC, Lehman JJ. PGC-1α and ERRα target gene downregulation is a signature of the failing human heart. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2009;46(2):201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rowe GC, Jiang A, Arany Z. PGC-1 coactivators in cardiac development and disease. Circulation Research. 2010;107(7):825–838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]