Abstract

We previously demonstrated in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice that deficiency or inhibition of aldose reductase (AR) caused significant dephosphorylation of hepatic transcriptional factor PPARα, leading to its activation and significant reductions in serum lipid levels. Herein, we report that inhibition of AR by zopolrestat or by a short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) against AR caused a significant reduction in serum and hepatic triglycerides levels in 10-week old diabetic db/db mice. Meanwhile, hyperglycemia-induced phosphorylation of hepatic ERK1/2 and PPARα was significantly attenuated in db/db mice treated with zopolrestat or AR shRNA. Further, in comparison with the untreated db/db mice, the hepatic mRNA expression of Aco and ApoA5, two target genes for PPARα, was increased by 93% (P < 0.05) and 73% (P < 0.05) in zopolrestat-treated mice, respectively. Together, these data indicate that inhibition of AR might lead to significant amelioration in hyperglycemia-induced dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

1. Introduction

The polyol pathway is a glucose metabolic shunt that is defined by two enzymatic reactions catalyzed by aldose reductase (AR, AKR1B1, EC1.1.1.21) and sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH, EC1.1.1.14), respectively [1, 2]. Biochemically, AR catalyzes the rate-limiting reduction of glucose to sorbitol, with the aid of cofactor NADPH. SDH converts sorbitol to fructose using NAD+. AR/the polyol pathway have been demonstrated to play important roles in the development and progression of diabetic complications in a number of tissues including kidney, retina, lens, and peripheral neuron tissues [3–5]. In the liver, however, the expression of AR is relatively low under normal physiological conditions [6, 7]. By contrast, the hepatic expression of sorbitol dehydrogenase, the second enzyme for the polyol pathway, is quite high [8]. Due to the relatively lower levels of expression of AR in the liver under normal situations, relatively little attention had been paid to its roles in the liver in the past. Recently, however, increasing evidence has suggested that hepatic AR is dynamically regulated under a variety of conditions. For instance, in rats fed with fructose, hepatic AR is significantly upregulated, which is associated with impaired activation of Stat3 and suppressed activity of PPARα in the liver [9]. In the Long Evans Cinnamon rats, induction of hepatic AR expression was shown to be associated with the development of hepatitis and hepatoma [10]. Similarly, significant upregulation of AR has also been demonstrated in other diseased liver tissues from rodents to humans [11–13].

The liver tissue plays a major role in energy metabolism, particularly glucose and lipid homeostasis. It is known that diabetes, type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in particular, is often associated with hepatic accumulation of triglycerides in both rodents and humans, which might eventually lead to the development of hepatic steatosis or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [14–16]. Recently, we demonstrated that deficiency or inhibition of AR caused significant dephosphorylation of hepatic PPARα, leading to the activation of this transcriptional factor as well significant reduction in serum TG levels in streptozotocin-(STZ-) diabetic mice, an experimental model for type I diabetes mellitus (T1DM) [17]. Because T2DM is clinically much predominant than T1DM, in this current study, we wanted to determine whether AR also affects PPARα in the liver of T2DM db/db mouse models. Furthermore, we wanted to determine how changes in AR activity might affect the hepatic lipid accumulation in the db/db mice. Our data suggest that inhibition of AR in the T2DM db/db mice led to significant activation in hepatic PPARα and significant reductions in serum triglycerides (TG) and hepatic TG, suggesting that under hyperglycemia, AR/the polyol pathway might be greatly upregulated to contribute significantly to the hepatic regulation of TG metabolism and the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies and Reagents

Antibodies were obtained from the following vendors, respectively: ERK1/2 and phospho-ERK1/2 (#9100), Cell Signaling (Beverly, Mass); PPARα (sc9000) and AR (sc17735), Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif); phosphoserine-12 PPARα (ab3484) and phosphoserine-21 PPARα (ab3485), Abcam (Cambridge, UK); β-actin (A1978), Sigma (St. Louis, Mo). Oil-red O and other reagents were of analytical grade quality and from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo). Zopolrestat (zopol) was synthesized by the Department of Medicine Chemistry, Pfizer Global Research and Development (Groton, Conn).

2.2. Lentivirus shRNA Construct

Recombinant lentiviral vector expressing small hairpin RNA (shRNA) against mouse AR (pLV-shAR) and its control (pLV-shNC) were constructed by inserting double-strand shRNA oligonucleotides into plasmid pLentiLox3.7 (pLL3.7) at the HapI and XhoI sites. Control and shRNA oligonucleotides against mouse AR were designed according to Ambion guidelines, with the sequences being 5′-ctggtcacacaacagaga-3′ and 5′-tacctaactcaggagaag-3′, respectively. Preparations of lentiviruses were performed by cotransfecting the lentiviral constructs with the packaging vectors into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus-containing supernatants were collected 48 h after infection. Viruses were recovered by ultracentrifugation at 110,000 ×g for 1.5 h and resuspended in PBS. Titers were determined by infecting 293T cells with serial dilutions of concentrated lentiviral preparations.

2.3. Animal Experiments

The animal experiments were conducted according to protocols and guidelines approved by the Xiamen University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The db/m (BKS.Cg-m/Leprdb/J) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) and bred to obtain six-week-old male db/db mice and their lean control db/m mice for this study. All animals were maintained on standard laboratory chow under a 12 : 12 h light-dark schedule. For AR inhibition by zopolrestat (zopol) treatment, six-week-old db/db mice were randomly divided into four experimental groups, namely, db/m mice, db/m mice + zopol, db/db mice, and db/db mice + zopol. For zopol treatments, the mice were administrated with 50 mg/kg body weight/day of zopol as a single daily intraperitoneal injection for 28 days. The same volumes of saline were also administrated to other control groups of mice. For in vivo AR knock-down experiments, six-week-old db/db mice were randomly grouped (4 mice/group). In vivo transduction of lentiviruses was achieved through tail vein injections of 0.1 mL of concentrated viral suspension with a viral titer of 1.0 × 109 IFU/mL in PBS. Twenty-eight days after zopol treatment or lentiviral injection, mice were sacrificed and tissues were dissected and immediately frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until use.

2.4. Semiquantitative Analyses of mRNA Expression by RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RT-PCR was performed to determine the levels of acetyl CoA oxidase (Aco), carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (Cpt1), apolipoprotein C-III (ApoC3), and apolipoprotein A-V (ApoA5) mRNAs as previously described [17]. The primers used were 5′-CCGCCACCTTCAATCCAGAGTTA-3′ and 5′-TCACAGTTGGGCTGTTGAGAATG-3′ (Aco), 5′-GGACGAATCGGAACAGGGATA-3′ and 5′-CCTTGTAATGTGCGAGCTGCA-3′ (Cpt1), 5′-CCTCTTGGCTCTCCTGGCATCT-3′ and 5′-TGCTCCAGTAGCCTTTCAGGG-3′ (ApoC3), 5′-GTGGGAGAAGACAC-CAAG-GCTC-3′ and 5′-GGTCAATGGCCTGAGTAAA-TGC-3′ (ApoA5), 5′-CGAGACCCCACTAA-CATCAAA-3′ and 5′-AGTCTTCTGGGTGGCA-GTGAT-3′ (GAPDH). DNA amplification was carried out using a High-Fidelity PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (TaKaRa). The PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. The integrated density values of the bands representing amplified products were acquired and analyzed by Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, USA).

2.5. Western Blot Analyses

Tissues were homogenized with Polytron in ice-cold buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerine, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 20 mM glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM sodium orthovanadate, and proteinase inhibitor mixture). The protein concentrations of the extracts were measured using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce). 40 μg protein of each sample was loaded and separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore). Blotted membranes were then incubated either anti-ERK or anti-phospho-ERK (1 : 1000) or anti-PPARα (1 : 500) or anti-phospho-PPARα (1 : 1000) or anti-AR (1 : 500) in TBS-0.1% Tween-20 with 5% nonfat milk at 4°C overnight. After several washes, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-goat IgG (1 : 2000) in TBS-0.1% Tween-20 with 5% nonfat milk. The detection was achieved using the supersignal chemiluminescent substrate kit (Pierce).

2.6. Blood Sample Analyses

Serum TG levels were measured using a colorimetric assay (Sigma, TR0100). Total serum cholesterol was measured using a cholesterol reagent kit (Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, China).

2.7. Liver TG Analyses

Liver TG was extracted by chloroform/methanol. Briefly, pulverized liver was homogenized in PBS, then extracted with chloroform/methanol (2 : 1), dried overnight, and resuspended in a solution of 60% butanol 40% Triton X-114/methanol (2 : 1). Liver total TG levels were measured using a colorimetric assay (Sigma, TR0100).

2.8. Oil-Red O Staining

Frozen liver sections of 10 μm thickness were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% oil-red O using standard procedures.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

All data were processed and analyzed by GraphPad software (Prism 5.0) and expressed as mean ± SEM. Students' t-test was used for pair-wise comparisons and one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test for multigroup analyses. Probability values less than 0.05 (*) were considered to be statistically significant; those less than 0.01 (**) more so.

3. Results

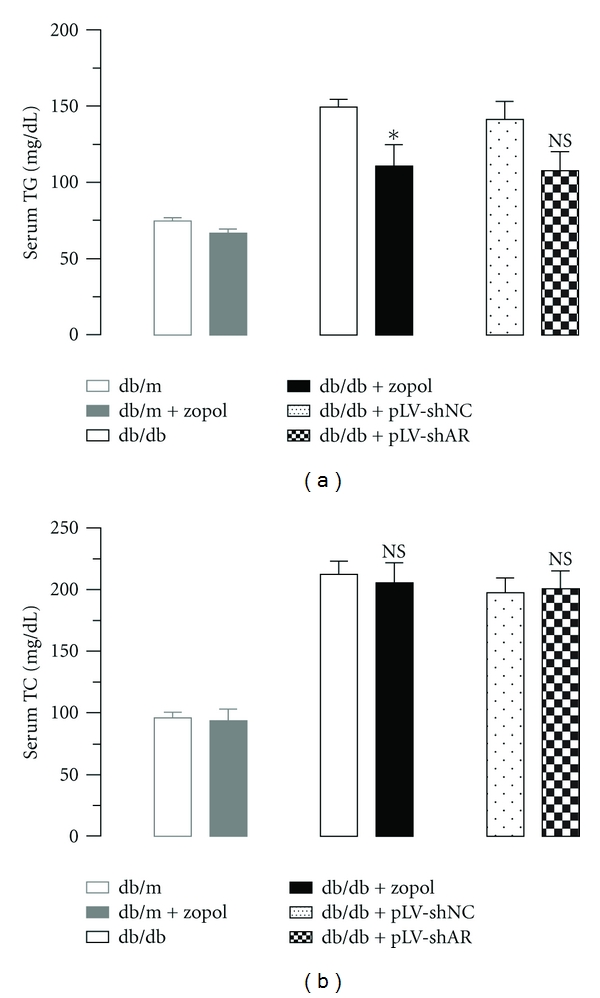

3.1. AR Inhibition-Reduced Serum TG but Not Serum TC Levels in Diabetic db/db Mice

To determine the effects of AR on systemic lipid metabolism, we measured the serum TG and TC levels in db/db mice after zopol treatment or AR knockdown (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 1(a), zopol treatment for 4 weeks caused a significant reduction in the serum TG levels in the 10-week-old male db/db mice (110.6 ± 14.17 mg/dL for db/db + zopol versus 149.3 ± 5.06 mg/dL for db/db, P < 0.05) but had little effects on the control db/m mice. A similar reduction in serum TG level was also observed in 10-week-old db/db mice transduced with lentiviruses carrying shRNA for AR (107.6 ± 12.38 mg/dL for db/db + pLV-shAR versus 141.6 ± 11.51 mg/dL for db/db + pLV-shNC, P > 0.05), although the difference was not significant statistically. In contrast to serum TG, no significant change in serum TC levels was observed in both db/db mice treated with zopol or db/db mice transduced with lentiviruses carrying AR shRNA (Figure 1(b)), which is consistent with our previous findings in the STZ-induced T1DM mouse model [17]. Together these results indicate that inhibition of AR leads to significant reductions in serum TG but not serum TC.

Figure 1.

Effect of zopol treatment or AR knock-down on serum TG levels (a) and TC levels (b) of db/db mice. Lean control mouse groups are db/m, n = 6 and db/m + zopol, n = 4; diabetic mouse groups are db/db, n = 6; db/db + zopol, n = 6 and db/db + pLV-shNC (n = 4); db/db + pLV-shAR (n = 4). Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; NS: not significant.

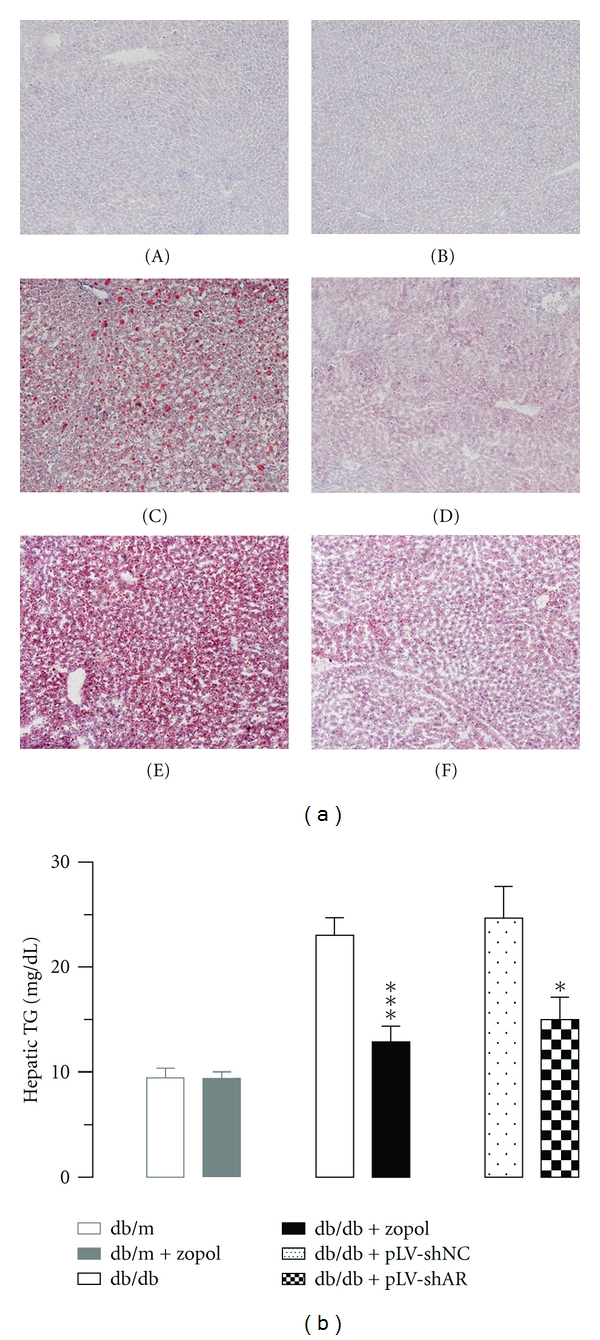

3.2. AR Inhibition-Reduced Hepatic TG in Diabetic db/db Mice

To determine how changes in AR expression and activity might affect hepatic lipid accumulation, we analyzed the TG contents in the liver tissues of 10-week-old male db/db mice after zopol treatment for 28 days or lentivirus-mediated AR knockdown. Oil-red O staining of liver tissues showed that substantial fat droplets were diffusely distributed in the hepatic lobules from the 10-week-old untreated db/db mice. In the liver of the db/db mice received zopol for 28 days, however, much little and smaller fat droplets were observed (Figure 2(a)). Similar reductions in hepatic lipid accumulation were observed in db/db mice treated with lentiviruses containing AR-shRNA expression cassette. The results from tissue staining were further confirmed by biochemical analyses of hepatic TG content (Figure 2(b)). Zopol treatment in db/db mice significantly reduced hepatic TG by about 60% (12.89 ± 1.47 mg/g tissue for db/db + zopol versus 23.06 ± 1.66 mg/g tissue for db/db, P < 0.001). Similarly, AR knockdown in db/db mice also significantly reduced hepatic TG by about 40% (14.99 ± 2.11 mg/g tissue for db/db + pLV-shAR versus 24.69 ± 3.02 mg/g tissue for db/db + pLV-shNC, P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of zopol treatment or AR knockdown on hepatic lipid in db/db mice. (a) Oil-red O staining of liver tissues of db/db mice after zopol treatment. (A) db/m; (B) db/m + zopol; (C) db/db; (D) db/db + zopol; (E) db/db + pLV-shNC; (F) db/db + pLV-shAR. Results are typical for 3 mice/group. Original magnification, ×100. (b) AR inhibition or AR knock-down reduced liver TG of db/db mice as analyzed chemically. Lean control mouse groups are db/m (n = 6) and db/m + zopol (n = 4); diabetic mouse groups are db/db (n = 6); db/db + zopol (n = 6) and db/db + pLV-shNC (n = 4); db/db + pLV-shAR (n = 4). Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

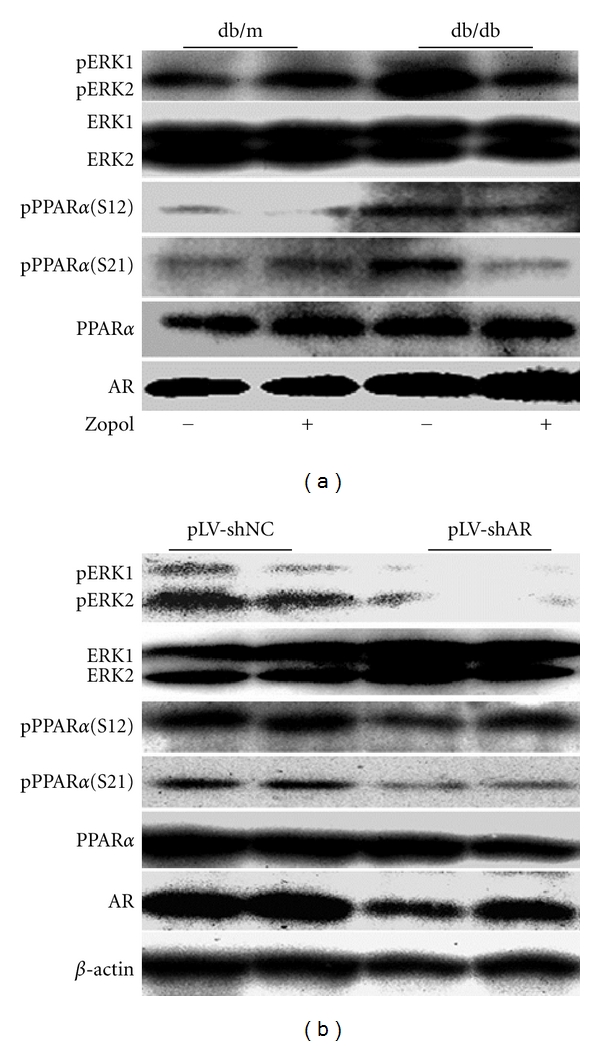

3.3. AR Inhibition Led to Significant Dephosphorylation of Hepatic ERK1/2 and PPARα in the db/db Mice

In STZ-induced T1DM mice, we demonstrated previously that AR deficiency or AR inhibition led to significant dephosphorylation of hepatic ERK1/2 and PPARα [17]. To determine whether this is also the case in the T2DM db/db mice, we examined the hepatic expression and phosphorylation of these proteins in 10-week-old db/db mice and its control db/m mice. As shown in Figure 3(a), with the elevation in hepatic AR expression in the db/db mice, the phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and PPARα (at Serine-12 and Serine-21) in the db/db mice was significantly enhanced. In db/db mice received zopol treatment for 28 days, however, the phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and PPARα was greatly attenuated. Noteworthy is that a slight increase in phosphoserine-21 PPARα level was also observed for db/m mice following the zopol treatment. However, statistical analyses indicated the increase in pPPARα (S21) in db/m mice with zopol is not significant (data not shown). Similar attenuations in phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and PPARα were also observed for db/db mice transduced with lentiviruses carrying shRNA for AR (Figure 3(b)). Together these results suggest that, consistent with the results from the STZ-induced T1DM mice, in vivo inhibition of AR in T2DM db/db mice also lead to dephosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and PPARα, which might eventually lead to the activation of hepatic PPARα to significantly affect hepatic lipid metabolism.

Figure 3.

Effects of AR on PPARα and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in db/db mice. (a) Representative Western blot for four independent experiments. Liver tissues were dissected and analyzed 28 days after zopol treatment. (b) Representative Western blot for four independent experiments. Liver tissues were dissected and analyzed 28 days after transduction with lentiviruses containing pLV-shAR or pLV-shNC. pERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2; pPPARα (S12), phosphoserine-12 PPARα; pPPARα (S21), phosphoserine-21 PPARα.

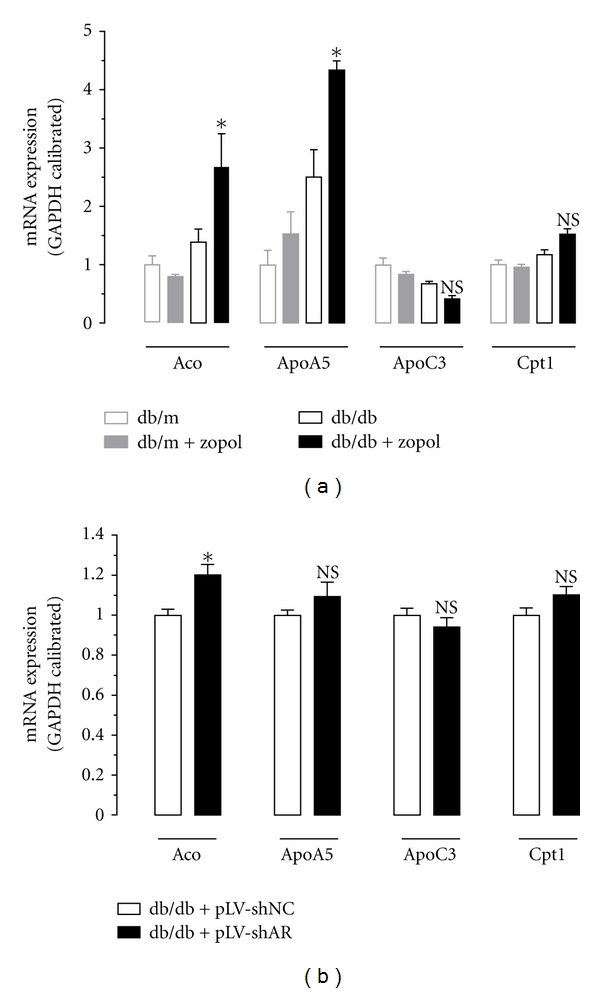

3.4. Dephosphorylation of PPARα Is Associated with Altered Expression of Hepatic Aco and ApoA5

To determine the effects of PPARα dephosphorylation on its target genes, we analyzed the expression of hepatic Aco, ApoA5, ApoC3, and Cpt-1 mRNAs by semiquantitative RT-PCR for liver tissues from the control mice and db/db mice received zopol treatment or db/db mice transduced with lentiviruses carrying AR shRNA. As shown in Figure 4(a), compared with untreated db/db mice, mRNA expression of Aco and ApoA5 in zopol-treated db/db mice elevated by approximately 93% (P < 0.05) and 73% (P < 0.05), respectively. Meanwhile, zopol-treated db/db mice had a slight but not significant lower hepatic expression of ApoC3 mRNA expression and a slight but not significant higher expression of Cpt-1 mRNA expression than the untreated db/db mice. The upregulation of hepatic Aco mRNA after zopol treatment was further confirmed in db/db mice transduced with lentiviruses carrying AR shRNA (Figure 4(b)). Probably due to incomplete knockdown, however, no significant changes were observed for hepatic mRNA expression of ApoA5, ApoC3, and Cpt-1. Together these data indicate that inhibition of AR caused activation of hepatic PPARα to alter the expression and activity of major hepatic enzymes involved in lipid homeostasis in the T2DM db/db mice, which might have significant impact on hepatic lipid accumulation and the development or progression of NASH and NAFLD.

Figure 4.

Hepatic mRNA expression of Aco, ApoA5, ApoC3, and Cpt-1 as analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR in db/db mice. (a) Liver tissues were dissected and analyzed 28 days after zopol treatment. (b) Liver tissues were dissected and analyzed 28 days after transduction with lentiviruses containing pLV-shAR or pLV-shNC. Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3-4). * P < 0.05; NS: not significant.

4. Discussion

AR/the polyol pathway is widely recognized to be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications such as cataracts, nephropathy, and neuropathy [4, 18]. In contrast, relatively little attention has been paid to their potential roles in the development of diabetic lipid disorders. In spite of this, several studies have shown the possible link between activation/deactivation of AR/the polyol pathway and altered regulation in lipid metabolism. It has been reported that in diabetic patients with dyslipidemia, there are significant increases in plasma or serum and urinary sorbitol and fructose, indicating that the increased flux in the polyol pathway is concomitant with diabetic dyslipidemia [19, 20]. Moreover, pharmacological administration of several AR inhibitors including zopol were shown to reduce blood TG in rats [21], tumor bearing mice [22], and diabetic human patients [23], respectively. More recently, our group reported that in STZ-induced T1DM mouse models, genetic AR deficiency or in vivo inhibition by chemical inhibitors of AR significantly improved hyperglycemia-induced dyslipidemia [17]. It is therefore of interest to determine whether AR regulates PPARα and affects hepatic lipid metabolism in T2DM models. In line with our expectation, we demonstrated in this current study that inhibition of AR by zopol treatment or transduction with lentiviruses carrying shRNA for AR greatly reduced hyperglycemia-induced lipid accumulation and hepatic steatosis in T2DM db/db mice. Furthermore, we showed that AR probably regulates hepatic lipid metabolism in part by modulating the status of PPARα phosphorylation to alter its activity.

In our current study, we utilized both chemical inhibitor and mRNA knockdown as means for the inhibition of AR. The inclusion of AR knockdown as an alternative approach for the inhibition of AR was necessary because we wanted to exclude the possible side or toxic effects and nonspecific inhibition that might be associated with chemical inhibitors of AR. Although both chemical inhibition and AR knock-down resulted in similar effects on hepatic lipid metabolism and mRNA expression levels of PPARα and its target genes, AR knockdown appeared to be slightly less effective than zopol treatment. This is probably due to incomplete knockdown of AR as only a single injection was performed and that was maintained for 4 weeks before the analyses.

The exact mechanisms underlying suppression of lipid accumulation or hepatic steatosis by inhibition of AR are not completely clear at this moment and require further investigations. At this moment, however, the mechanisms for increased lipid degradation and mechanisms for decreased lipid synthesis both appear to be functional. Our demonstration that inhibition of AR led to the activation of PPARα through its dephosphorylation contributes in part to increased hepatic lipid degradation following inhibition of AR. It is well established that PPARα is a central regulator for hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism as well as the development of lipid disorders including hepatic steatosis and NAFLD [24–29]. Once activated, it will tend to promote lipid catabolism by upregulating the expression of lipid catabolic enzymes such as lipoprotein lipase and ApoA5 [30] and downregulating ApoC3 [31]. Consistent with this, two important lipid catabolic enzymes Aco and ApoA5 were significantly upregulated as a consequence of PPARα activation, although not much change in mRNA expression was observed for Cpt1 and ApoC3. Inhibition of AR, on the other hand, might also result in reduced lipid synthesis. Under hyperglycemic conditions, for example, abundant glucose might be channeled into the hyperglycemia-activated AR/the polyol pathway to generate a substantial amount of fructose in the liver. Fructose has long been known to be highly lipogenic and can contribute significantly to hepatic lipogenesis, adipogenesis, insulin resistance, obesity, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, and NAFLD [9, 32–47] in both human and rodents. When AR is inhibited or when the polyol pathway is blocked, it can therefore be expected that endogenous hepatic fructose generation will be greatly reduced such that fructose-induced lipogenesis in the liver will also be suppressed, thereby leading to the suppression of hepatic steatosis or NAFLD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (no. 2009J01180), the Science Planning Program of Fujian Province (no. 2010J1008), and the National Science Foundation of China (no. 30970649).

Abbreviations

- Aco:

Acetyl CoA oxidase

- ApoA5:

Apolipoprotein A-V

- ApoC3:

Apolipoprotein C-III

- AR:

Aldose reductase

- Cpt1:

Carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1

- ERK:

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- NAFLD:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH:

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PPARα:

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- RT-PCR:

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- shRNA:

Short-hairpin RNA

- TG:

Triglyceride

- T1DM:

Type I diabetes mellitus

- T2DM:

Type II diabetes mellitus

- zopol:

Zopolrestat.

References

- 1.Hers HG. Aldose reductase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1960;37(1):120–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements RS. The polyol pathway. A historical review. Drugs. 1986;32(2):3–5. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198600322-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oates PJ, Mylari BL. Aldose reductase inhibitors: therapeutic implications for diabetic complications. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 1999;8(12):2095–2119. doi: 10.1517/13543784.8.12.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexiou P, Pegklidou K, Chatzopoulou M, Nicolaou I, Demopoulos VJ. Aldose reductase enzyme and its implication to major health problems of the 21st century. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;16(6):734–752. doi: 10.2174/092986709787458362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markus HB, Raducha M, Harris H. Tissue distribution of mammalian aldose reductase and related enzymes. Biochemical Medicine. 1983;29(1):31–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(83)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements RS, Weaver JP, Winegrad AL. The distribution of polyol: NADP oxidoreductase in mammalian tissues. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1969;37(2):347–353. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffery J, Jornvall H. Enzyme relationships in a sorbitol pathway that bypasses glycolysis and pentose phosphates in glucose metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1983;80(4 I):901–905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roglans N, Vila L, Farre M, et al. Impairment of hepatic Stat-3 activation and reduction of PPARα activity in fructose-fed rats. Hepatology. 2007;45:778–788. doi: 10.1002/hep.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi M, Hoshi A, Fujii J, et al. Induction of aldose reductase gene expression in LEC rats during the development of the hereditary hepatitis and hepatoma. Japanese Journal of Cancer Research. 1996;87(4):337–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb00227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi M, Fujii J, Miyoshi E, Hoshi A, Taniguchi N. Elevation of aldose reductase gene expression in rat primary hepatoma and hepatoma cell lines: implication in detoxification of cytotoxic aldehydes. International Journal of Cancer. 1995;62(6):749–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KWY, Ko BCB, Jiang Z, Cao D, Chung SSM. Overexpression of aldose reductase in liver cancers may contribute to drug resistance. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2001;12(2):129–132. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeindl-Eberhart E, Haraida S, Liebmann S, et al. Detection and identification of tumor-associated protein variants in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2004;39(2):540–549. doi: 10.1002/hep.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cusi K. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 2009;16(2):141–149. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283293015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanyal AJ. NASH: a global health problem. Hepatology Research. 2011;41(7):670–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Zhang J, Cai S, Dong J, Yang JY, Chen Z. Metabonomics studies of intact hepatic and renal cortical tissues from diabetic db/db mice using high-resolution magic-angle spinning 1H NMR spectroscopy. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2009;393(6-7):1657–1668. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu L, Wu X, Chau JFL, et al. Aldose reductase regulates hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α phosphorylation and activity to impact lipid homeostasis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(25):17175–17183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yabe-Nishimura C. Aldose reductase in glucose toxicity: a potential target for the prevention of diabetic complications. Pharmacological Reviews. 1998;50(1):21–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki T, Akanuma H, Yamanouchi T. Increased fructose concentrations in blood and urine in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):353–357. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshii H, Uchino H, Ohmura C, Watanabe K, Tanaka Y, Kawamori R. Clinical usefulness of measuring urinary polyol excretion by gas-chromatography/mass-spectrometry in type 2 diabetes to assess polyol pathway activity. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2001;51(2):115–123. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallai-Sanfacon M. Method of lowering lipid levels. US patent #4,492,706, 1985.

- 22.Kawamura M, Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, et al. Aldose reductase: an aldehyde scavenging enzyme in the intraneuronal metabolism of norepinephrine in human sympathetic ganglia. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical. 2002;96(2):131–139. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(01)00385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson MJ. Method of lowering blood lipid levels. US patent #5,391,551, 1995.

- 24.Abdelmegeed MA, Yoo SH, Henderson LE, Gonzalez FJ, Woodcroft KJ, Song BJ. PPARα expression protects male mice from high fat-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver. Journal of Nutrition. 2011;141(4):603–610. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djouadi F, Weinheimer CJ, Saffitz JE, et al. A gender-related defect in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-deficient mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102(6):1083–1091. doi: 10.1172/JCI3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duval C, Muller M, Kersten S. PPARα and dyslipidemia. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1771:961–971. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ip E, Farrell GC, Robertson G, Hall P, Kirsch R, Leclercq I. Central role of PPARα-dependent hepatic lipid turnover in dietary steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2003;38(1):123–132. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pyper SR, Viswakarma N, Yu S, Reddy JK. PPARalpha: energy combustion, hypolipidemia, inflammation and cancer. Nuclear Receptor Signaling. 2010;8:p. e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu HT, Chen CT, Cheng KC, Li YX, Yeh CH, Cheng JT. Pharmacological activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta Improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in high fat diet-induced diabetic mice. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2011;43:631–635. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vu-Dac N, Gervois P, Jakel H, et al. Apolipoprotein A5, a crucial determinant of plasma triglyceride levels, is highly responsive to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α activators. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(20):17982–17985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Auwerx J, Schoonjans K, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Transcriptional control of triglyceride metabolism: fibrates and fatty acids change the expression of the LPL and apo C-III genes by activating the nuclear receptor PPAR. Atherosclerosis. 1996;124:S29–S37. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05854-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jürgens H, Haass W, Castañeda TR, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened beverages increases body adiposity in mice. Obesity Research. 2005;13(7):1145–1156. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott SS, Keim NL, Stern JS, Teff K, Havel PJ. Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76(5):911–922. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samuel VT. Fructose induced lipogenesis: from sugar to fat to insulin resistance. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;22(2):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dekker MJ, Su Q, Baker C, Rutledge AC, Adeli K. Fructose: a highly lipogenic nutrient implicated in insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and the metabolic syndrome. American Journal of Physiology. 2010;299(5):E685–E694. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00283.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anania FA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and fructose: bad for us, better for mice. Journal of Hepatology. 2011;55(1):218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alisi A, Manco M, Pezzullo M, Nobili V. Fructose at the center of necroinflammation and fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):372–373. doi: 10.1002/hep.23873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim JS, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A, Schwarz JM, Lustig RH. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;7(5):251–264. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tetri LH, Basaranoglu M, Brunt EM, Yerian LM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Severe NAFLD with hepatic necroinflammatory changes in mice fed trans fats and a high-fructose corn syrup equivalent. American Journal of Physiology. 2008;295(5):G987–G995. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90272.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagata R, Nishio Y, Sekine O, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism (-468 Gly to Ala) at the promoter region of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c associates with genetic defect of fructose-induced hepatic lipogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(28):29031–29042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagata R, Nishio Y, Sekine O, et al. Erratum: Single nucleotide polymorphism (-468 Gly to Ala) at the promoter region of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c associates with genetic defect of fructose-induced hepatic lipogenesis (Journal of Biological Chemistry (2004) 279 (29031-29042)) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(35):p. 37210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park J, Lemieux S, Lewis GF, Kuksis A, Steiner G. Chronic exogenous insulin and chronic carbohydrate supplementation increase de novo VLDL triglyceride fatty acid production in rats. Journal of Lipid Research. 1997;38(12):2529–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roglans N, Bellido A, Rodríguez C, et al. Fibrate treatment does not modify the expression of acyl coenzyme A oxidase in human liver. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002;72(6):692–701. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.128605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackerman Z, Oron-Herman M, Grozovski M, et al. Fructose-induced fatty liver disease: hepatic effects of blood pressure and plasma triglyceride reduction. Hypertension. 2005;45(5):1012–1018. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164570.20420.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanuri G, Spruss A, Wagnerberger S, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. Fructose-induced steatosis in mice: role of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and NKT cells. Laboratory Investigation. 2011;91(6):885–895. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song M, Schuschke DA, Zhou Z, et al. High fructose feeding induces copper deficiency in sprague-dawley rats: a novel mechanism for obesity related fatty liver. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.030. Journal of Hepatology. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdelmalek MF, Suzuki A, Guy C, et al. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(6):1961–1971. doi: 10.1002/hep.23535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]