Abstract

Some selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as raloxifene and tamoxifen, are neuroprotective and reduce brain inflammation in several experimental models of neurodegeneration. In addition, raloxifene and tamoxifen counteract cognitive deficits caused by gonadal hormone deprivation in male rats. In this study, we have explored whether raloxifene and tamoxifen may regulate the number and geometry of dendritic spines in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat hippocampus. Young adult male rats were injected with raloxifene (1 mg/kg), tamoxifen (1 mg/kg), or vehicle and killed 24 h after the injection. Animals treated with raloxifene or tamoxifen showed an increased numerical density of dendritic spines in CA1 pyramidal neurons compared to animals treated with vehicle. Raloxifene and tamoxifen had also specific effects in the morphology of spines. These findings suggest that raloxifene and tamoxifen may influence the processing of information by hippocampal pyramidal neurons by affecting the number and shape of dendritic spines.

1. Introduction

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) either synthetic or natural, such as phytoestrogens, are candidates for the treatment or the prevention of cognitive and affective disorders in men and women [1–5]. Several studies have shown that some synthetic SERMs, such as tamoxifen, raloxifene, or bazedoxifene [6–29], some nonfeminizing estrogens [30–34], and some natural SERMs, such as genistein [35, 36], are neuroprotective in vitro and in vivo. The neuroprotective effects of SERMs are associated with a decrease in the activation of microglia and astroglia and a reduction in brain inflammation [37–43]. In addition, some SERMs have shown to induce neuritic outgrowth in vitro [44, 45], suggesting that these molecules may also affect synaptic connectivity in vivo. Indeed, ERs are involved in the regulation of dendritic spines in the hippocampus of female animals in vivo [46–51], where tamoxifen regulates synaptophysin expression [52]. SERMs are also able to regulate cholinergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmission in female animals [53–56]. However, the effects of SERMs on synaptic connectivity in males have not been adequately explored. Nevertheless, previous studies have shown that SERMs such as raloxifene and tamoxifen are able to counteract hippocampus-dependent cognitive deficits caused by androgen deprivation in male rats [57]. In addition, raloxifene reduces working memory deficits in male rats after traumatic brain injury [20].

To further characterize the mechanisms of action of SERMs in the male brain, we have assessed in this study the effects of tamoxifen and raloxifene on the number and geometry of dendritic spines in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat hippocampus.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals and Treatments

Sprague-Dawley adult male rats were maintained under regular 12 h light-dark cycles (lights on: 07:00–19:00 h) and controlled environmental humidity (45–50%) and temperature (22 ± 2°C). Animals had free access to food and water. All the experimental procedures were conducted to minimize pain or discomfort in the animals and performed in accordance with the NIH guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications no. 80-23, 1996 revised). Protocols were approved by our institutional animal care committee.

At the age of three months, animals were injected with raloxifene (1 mg/kg; n = 6), tamoxifen (1 mg/kg; n = 6), or vehicle (20 mg/mL DMSO diluted 3% in saline solution; n = 6). Animals were killed 24 h after the injection.

2.2. Golgi Studies

Animals were anesthetized with 30 mg/kg intramuscular ketamine and 50 mg/kg i.p. sodium pentobarbital. Then, animals were perfused intracardially with 100 mL of a washing phosphate-buffered solution (pH 7.4; 0.01 M) containing 1000 IU/L of sodium heparin and 1 g/L of procaine hydrochloride. Then, 200 mL of a fixing phosphate-buffered 4% formaldehyde solution was perfused. Both solutions flowed at a rate of 11.5 mL/min. Each brain remained for at least 48 h in 100 mL of a fresh fixing solution.

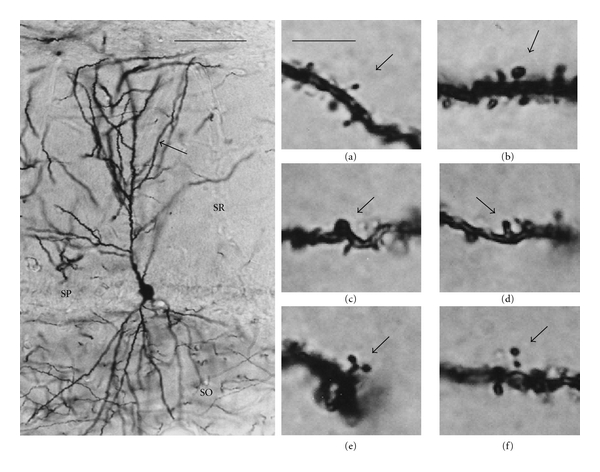

The bilateral dorsal hippocampi were dissected out and impregnated using a modification of the Golgi method [58]. Several coronal slices 100 μm thick were mounted on one slide per animal. Spine numerical density and the proportion of thin, mushroom, stubby, wide, branched, and double spines [59–61] were assessed in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Spines were counted in one 50 μm segment per cell, located in the middle of one of the secondary dendrites that protrude from the apical dendrite (Figure 1). Six CA1 pyramidal neurons were studied per animal. The total number of spines counted was 5,796 in the animals treated with vehicle: 9,295 in the animals treated with raloxifene and 9,180 in the animals treated with tamoxifen.

Figure 1.

Examples of dendritic spines stained with the Golgi method. Left panel: photomicrograph of a CA1 pyramidal neuron impregnated with a modification of the Golgi method. Spines studied in the present work were counted in a segment 50 μm in length of a secondary dendrite (arrow) protruding from its parent apical dendrite. SO: stratum oriens; SP: stratum pyramidale; SR: stratum radiatum. Scale bar = 100 μm. In the right panels, photomicrographs show representative examples of thin (a), mushroom (b), stubby (c), wide (d), branched (e), and double (f) spines (arrows). Scale bar = 5 μm.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The one-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test were used for statistical comparisons of data from spine numerical density. In addition, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni correction post hoc test were used for statistical comparisons of the proportion of the different types of spines. The n used for statistical analysis was the number of animals (n = 6, per experimental group).

3. Results

Raloxifene and tamoxifen increased significantly the total numerical density of dendritic spines compared to control animals (Table 1). Both SERMs increased the numerical density of mushroom, stubby, and wide spines (Table 1). In addition, raloxifene increased the numerical density of thin spines (Table 1). Numerical density of mushroom spines was greater in tamoxifen-treated rats than in raloxifene-treated animals. In contrast, thin and wide spines were less numerous in the tamoxifen group than in raloxifene-treated animals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Numerical density of dendritic spines in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of male rats 24 hours after the treatment with vehicle, raloxifene, or tamoxifen.

| Vehicle | Raloxifene | Tamoxifen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total spines | 161.0 ± 5.0 | 258.2 ± 3.0a | 255.0 ± 4.0b |

| Thin | 74.8 ± 2.8 | 89.6 ± 3.8a | 78.0 ± 3.6c |

| Mushroom | 50.4 ± 1.8 | 84.6 ± 3.2a | 92.8 ± 1.6bc |

| Stubby | 28.6 ± 1.4 | 65.8 ± 1.8a | 71.0 ± 2.2b |

| Wide | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 15.6 ± 1.0a | 11.8 ± 1.2bc |

| Branched | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Double | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

Data represent mean ± SEM of the number of dendritic spines per 100 μm dendritic segment from 6 animals in each experimental group. a–cSignificant differences, P < 0.05; araloxifene versus Vehicle; btamoxifen versus. Vehicle; ctamoxifen versus Raloxifene.

The experimental treatments also resulted in changes in the proportion of different spine morphologies. The proportion of thin spines was reduced in the animals treated with raloxifene. Furthermore, raloxifene increased the proportion of stubby and wide spines and did not significantly affect the proportion of mushroom, branched and double spines (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion (%) of the different types of dendritic spines in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons 24 hours after the treatment with vehicle, raloxifene, or tamoxifen.

| Vehicle | Raloxifene | Tamoxifen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thin | 46.4 | 34.7a | 30.5b |

| Mushroom | 31.3 | 32.7 | 36.3bc |

| Stubby | 17.7 | 25.4a | 27.8b |

| Wide | 3.8 | 6.0a | 4.6 |

| Branched | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Double | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.1 |

Data represent means from 6 animals in each experimental group. a–cSignificant differences, P < 0.05; araloxifene versus Vehicle; btamoxifen versus Vehicle; ctamoxifen versus raloxifene.

As observed for raloxifene, the proportion of thin spines was also reduced in the animals treated with tamoxifen. In contrast, mushroom and stubby spines were seen in greater proportion in animals treated with tamoxifen than in control animals. Tamoxifen had no significant effects in the proportion of wide, branched, and double spines (Table 2). The animals treated with tamoxifen showed a higher proportion of mushroom spines than those treated with raloxifene (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Our present findings indicate that some SERMs, such as raloxifene and tamoxifen, affect the number of dendritic spines in male rats. This action of SERMs may affect the processing of novel information used in memory formation [62].

In addition to increase the numerical density of spines, raloxifene and tamoxifen also affected spine geometry. Both SERMs increased the numerical density of stubby, mushroom, and wide spines. In addition, raloxifene increased the number of thin spines. However, both SERMs reduced the proportion of thin dendritic spines. Dendritic spine morphology affects the diffusion and compartmentalization of membrane-associated proteins [63] and the expression of AMPA receptors [64–67]. In particular, the length of the spine neck seems to be a key regulator of spinodendritic Ca2+ signaling [68–72] and of the transmission of membrane potentials [73]. In consequence, the geometry of dendritic spines may influence the processing of synaptic impulses [74–79]. Our findings suggest, therefore, that raloxifene and tamoxifen, decreasing the proportion of thin dendritic spines, may influence the processing of information by hippocampal pyramidal neurons. In addition, the action of raloxifene and tamoxifen presents some differences that may have functional significance. Tamoxifen, but not raloxifene, increased the proportion of mushroom spines. Thus, the animals treated with tamoxifen had an increased numerical density and proportion of mushroom spines compared to animals treated with raloxifene. Mushroom spines may be involved in the management of previously acquired information since they have larger postsynaptic densities [80] and express higher levels of AMPA receptors [64–67]. Therefore, the synapses on mushroom spines are functionally stronger [78] and it has been suggested that these spines would sustain memory storage [78, 81, 82].

The induction of plastic changes in dendritic spines by raloxifene and tamoxifen may be linked with the precognitive effects of these molecules in male rats [20, 57]. However, the possible impact of raloxifene and tamoxifen on cognitive decline in men remains to be adequately explored, in particular in association with neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, both SERMs increase the levels of luteinizing hormone (LH) in men [83] and it has been proposed that elevated levels of LH may contribute to Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis [84]. Indeed, leuprolide acetate, a GnRH agonist that lower serum levels of LH, has been shown to improve cognitive performance and decrease amyloid-β deposition in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease [85].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that raloxifene and tamoxifen, two SERMs currently used in clinical treatments, promote an increase in the numerical density of dendritic spines and changes in spine geometry in the hippocampus of male rats. These findings, together with the regulation exerted by tamoxifen and raloxifene on hippocampus-dependent cognitive function in male rats [57], suggest that SERMs may influence the processing of information by male hippocampal pyramidal neurons by affecting the number and shape of dendritic spines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Coordinación de Investigación en Salud, IMSS (FIS/IMSS/PROT/G10/821), Universidad de Guadalajara (U de G, P3e), México, and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Madrid, Spain (BFU2008-02950-C03-01).

References

- 1.Brinton RD. Requirements of a brain selective estrogen: advances and remaining challenges for developing a NeuroSERM. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2004;6(supplement):S27–S35. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6s607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernardi F, Pluchino N, Stomati M, Pieri M, Genazzani AR. CNS: sex steroids and SERMs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;997:378–388. doi: 10.1196/annals.1290.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao L, O’Neill K, Diaz Brinton R. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for the brain: current status and remaining challenges for developing NeuroSERMs. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;49(3):472–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DonCarlos LL, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroprotective actions of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(supplement 1):S113–S122. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arevalo MA, Santos-Galindo M, Lagunas N, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective estrogen receptor modulators as brain therapeutic agents. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2011;46(1):R1–R9. doi: 10.1677/JME-10-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhandapani KM, Brann DW. Protective effects of estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators in the brain. Biology of Reproduction. 2002;67(5):1379–1385. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.003848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciriza I, Carrero P, Azcoitia I, Lundeen SG, Garcia-Segura LM. Selective estrogen receptor modulators protect hippocampal neurons from kainic acid excitotoxicity: differences with the effect of estradiol. Journal of Neurobiology. 2004;61(2):209–221. doi: 10.1002/neu.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bebo BF, Dehghani B, Foster S, Kurniawan A, Lopez FJ, Sherman LS. Treatment with selective estrogen receptor modulators regulates myelin specific T-cells and suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. GLIA. 2009;57(7):777–790. doi: 10.1002/glia.20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao L, O’Neill K, Brinton RD. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for the brain: current status and remaining challenges for developing NeuroSERMs. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;49(3):472–493. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao L, O’Neill K, Brinton RD. Estrogenic agonist activity of ICI 182,780 (Faslodex) in hippocampal neurons: implications for basic science understanding of estrogen signaling and development of estrogen modulators with a dual therapeutic profile. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006;319(3):1124–1132. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.109504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benvenuti S, Luciani P, Vannelli GB, et al. Estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators exert neuroprotective effects and stimulate the expression of Selective Alzheimer’s Disease Indicator-1, a recently discovered antiapoptotic gene, in human neuroblast long-term cell cultures. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2005;90(3):1775–1782. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biewenga E, Cabell L, Audesirk T. Estradiol and raloxifene protect cultured SN4741 neurons against oxidative stress. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;373(3):179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourque M, Liu B, Dluzen DE, Di Paolo T. Tamoxifen protects male mice nigrostriatal dopamine against methamphetamine-induced toxicity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2007;74(9):1413–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callier S, Morissette M, Grandbois M, Pelaprat D, Di Paolo T. Neuroprotective properties of 17β-estradiol, progesterone, and raloxifene in MPTP C57Bl/6 mice. Synapse. 2001;41(2):131–138. doi: 10.1002/syn.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du B, Ohmichi M, Takahashi K, et al. Both estrogen and raloxifene protect against β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in estrogen receptor α-transfected PC12 cells by activation of telomerase activity via Akt cascade. Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;183(3):605–615. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y, Fratkins JD, LeBlanc MH. Treatment with tamoxifen reduces hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2004;484(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandbois M, Morissette M, Callier S, Di Paolo T. Ovarian steroids and raloxifene prevent MPTP-induced dopamine depletion in mice. NeuroReport. 2000;11(2):343–346. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200002070-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimelberg HK. Tamoxifen as a powerful neuroprotectant in experimental stroke and implications for human stroke therapy. Recent Patents on CNS Drug Discovery. 2008;3(2):104–108. doi: 10.2174/157488908784534603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimelberg HK, Jin Y, Charniga C, Feustel PJ. Neuroprotective activity of tamoxifen in permanent focal ischemia. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2003;99(1):138–142. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.1.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kokiko ON, Murashov AK, Hoane MR. Administration of raloxifene reduces sensorimotor and working memory deficits following traumatic brain injury. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;170(2):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee ESY, Yin Z, Milatovic D, Jiang H, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen protect against Mn-induced toxicity in rat cortical primary cultures of neurons and astrocytes. Toxicological Sciences. 2009;110(1):156–167. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee ESY, Sidoryk M, Jiang H, Yin Z, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen reverse manganese-induced glutamate transporter impairment in astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;110(2):530–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei DL, Long JM, Hengemihle J, et al. Effects of estrogen and raloxifene on neuroglia number and morphology in the hippocampus of aged female mice. Neuroscience. 2003;121(3):659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMurray R, Islamov R, Murashov AK. Raloxifene analog LY117018 enhances the regeneration of sciatic nerve in ovariectomized female mice. Brain Research. 2003;980(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02984-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta SH, Dhandapani KM, De Sevilla LM, Webb RC, Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, reduces ischemic damage caused by middle cerebral artery occlusion in the ovariectomized female rat. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;77(1):44–50. doi: 10.1159/000068332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mickley KR, Dluzen DE. Dose-response effects of estrogen and tamoxifen upon methamphetamine- induced behavioral responses and neurotoxicity of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system in female mice. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79(6):305–316. doi: 10.1159/000079710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morissette M, Sweidi SA, Callier S, Di Paolo T. Estrogen and SERM neuroprotection in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2008;290(1-2):60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossberg MI, Murphy SJ, Traystman RJ, Hurn PD. LY353381.HCl, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, and experimental stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(12):3041–3046. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Xie M, Schools GP, et al. Tamoxifen mediated estrogen receptor activation protects against early impairment of hippocampal neuron excitability in an oxygen/glucose deprivation brain slice ischemia model. Brain Research. 2009;1247:196–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green PS, Yang SH, Nilsson KR, Kumar AS, Covey DF, Simpkins JW. The nonfeminizing enantiomer of 17β-estradiol exerts protective effects in neuronal cultures and a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Endocrinology. 2001;142(1):400–406. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung ME, Wilson AM, Simpkins JW. A nonfeminizing estrogen analog protects against ethanol withdrawal toxicity in immortalized hippocampal cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006;319(2):543–550. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu R, Yang SH, Perez E, et al. Neuroprotective effects of a novel non-receptor-binding estrogen analogue: in vitro and in vivo analysis. Stroke. 2002;33(10):2485–2491. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000030317.43597.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpkins JW, Wen Y, Perez E, Yang S, Wang X. Role of nonfeminizing estrogens in brain protection from cerebral ischemia: an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2005;1052:233–242. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Dykens JA, Perez E, et al. Neuroprotective effects of 17β-estradiol and nonfeminizing estrogens against H2O2 toxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;70(1):395–404. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azcoitia I, Moreno A, Carrero P, Palacios S, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroprotective effects of soy phytoestrogens in the rat brain. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2006;22(2):63–69. doi: 10.1080/09513590500519161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schreihofer DA, Redmond L. Soy phytoestrogens are neuroprotective against stroke-like injury in vitro. Neuroscience. 2009;158(2):602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei DL, Long JM, Hengemihle J, et al. Effects of estrogen and raloxifene on neuroglia number and morphology in the hippocampus of aged female mice. Neuroscience. 2003;121(3):659–666. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tapia-Gonzalez S, Carrero P, Pernia O, Garcia-Segura LM, Diz-Chaves Y. Selective oestrogen receptor (ER) modulators reduce microglia reactivity in vivo after peripheral inflammation: potential role of microglial ERs. Journal of Endocrinology. 2008;198(1):219–230. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cerciat M, Unkila M, Garcia-Segura LM, Arevalo MA. Selective estrogen receptor modulators decrease the production of interleukin-6 and interferon-γ-inducible protein-10 by astrocytes exposed to inflammatory challenge in vitro. GLIA. 2010;58(1):93–102. doi: 10.1002/glia.20904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suuronen T, Nuutinen T, Huuskonen J, Ojala J, Thornell A, Salminen A. Anti-inflammatory effect of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in microglial cells. Inflammation Research. 2005;54(5):194–203. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1343-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barreto G, Santos-Galindo M, Diz-Chaves Y, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators decrease reactive astrogliosis in the injured brain: effects of aging and prolonged depletion of ovarian hormones. Endocrinology. 2009;150(11):5010–5015. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu JL, Tian DS, Li ZW, et al. Tamoxifen alleviates irradiation-induced brain injury by attenuating microglial inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Brain Research. 2010;1316:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tian DS, Liu JL, Xie MJ, et al. Tamoxifen attenuates inflammatory-mediated damage and improves functional outcome after spinal cord injury in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;109(6):1658–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nilsen J, Mor G, Naftolin F. Raloxifene induces neurite outgrowth in estrogen receptor positive PC12 cells. Menopause. 1998;5(4):211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Neill K, Chen S, Brinton RD. Impact of the selective estrogen receptor modulator, tamoxifen, on neuronal outgrowth and survival following toxic insults associated with aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Experimental Neurology. 2004;188(2):268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gould E, Woolley CS, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10(4):1286–1291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;336(2):293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McEwen BS, Woolley CS. Estradiol and progesterone regulate neuronal structure and synaptic connectivity in adult as well as developing brain. Experimental Gerontology. 1994;29(3-4):431–436. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy DD, Segal M. Regulation of dendritic spine density in cultured rat hippocampal neurons by steroid hormones. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(13):4059–4068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04059.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woolley CS. Estrogen-mediated structural and functional synaptic plasticity in the female rat hippocampus. Hormones and Behavior. 1998;34(2):140–148. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu F, Day M, Muñiz LC, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor-β regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity and improves memory. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11(3):334–343. doi: 10.1038/nn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharma K, Mehra RD, Dhar P, Vij U. Chronic exposure to estrogen and tamoxifen regulates synaptophysin and phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein expression in CA1 of ovariectomized rat hippocampus. Brain Research. 2007;1132(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu X, Glinn MA, Ostrowski NL, et al. Raloxifene and estradiol benzoate both fully restore hippocampal choline acetyltransferase activity in ovariectomized rats. Brain Research. 1999;847(1):98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cyr M, Landry M, Di Paolo T. Modulation by estrogen-receptor directed drugs of 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A receptors in rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sánchez MG, Bourque M, Morissette M, Di Paolo T. Steroids-dopamine interactions in the pathophysiology and treatment of cns disorders. CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics. 2010;16(3):e43–e71. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith LJ, Henderson JA, Abell CW, Bethea CL. Effects of ovarian steroids and raloxifene on proteins that synthesize, transport, and degrade serotonin in the raphe region of macaques. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(11):2035–2045. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lagunas N, Calmarza-Font I, Grassi D, Garcia-Segura LM. Estrogen receptor ligands counteract cognitive deficits caused by androgen deprivation in male rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2011;59(4):581–584. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez-Burgos I, Tapia-Arizmendi G, Feria-Velasco A. Golgi method without osmium tetroxide for the study of the central nervous system. Biotechnic and Histochemistry. 1992;67(5):288–296. doi: 10.3109/10520299209110037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters A, Kaiserman-Abramof IR. The small pyramidal neuron of the rat cerebral cortex—the synapses upon dendritic spines. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie. 1969;100(4):487–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00344370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarelo-Acuña L, Olvera-Cortés E, González-Burgos I. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to ethanol induces changes in the shape of the dendritic spines from hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;286(1):13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González-Burgos I, Alejandre-Gómez M, Cervantes M. Spine-type densities of hippocampal CA1 neurons vary in proestrus and estrus rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;379(1):52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leuner B, Shors TJ. New spines, new memories. Molecular Neurobiology. 2004;29(2):117–130. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:2:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hugel S, Abegg M, De Paola V, Caroni P, Gähwiler BH, McKinney RA. Dendritic spine morphology determines membrane-associated protein exchange between dendritic shafts and spine heads. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(3):697–702. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GCR, Nemoto T, Miyashita Y, Iino M, Kasai H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2001;4(11):1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganeshina O, Berry RW, Petralia RS, Nicholson DA, Geinisman Y. Synapses with a segmented, completely partitioned postsynaptic density express more AMPA receptors than other axospinous synaptic junctions. Neuroscience. 2004;125(3):615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ashby MC, Maier SR, Nishimune A, Henley JM. Lateral diffusion drives constitutive exchange of AMPA receptors at dendritic spines and is regulated by spine morphology. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(26):7046–7055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1235-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nimchinsky EA, Yasuda R, Oertner TG, Svoboda K. The number of glutamate receptors opened by synaptic stimulation in single hippocampal spines. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(8):2054–2064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5066-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Majewska A, Tashiro A, Yuste R. Regulation of spine calcium dynamics by rapid spine motility. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(22):8262–8268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08262.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yuste R, Majewska A, Holthoff K. From form to function: calcium compartmentalization in dendritic spines. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(7):653–659. doi: 10.1038/76609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hayashi Y, Majewska AK. Dendritic spine geometry: functional implication and regulation. Neuron. 2005;46(4):529–532. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noguchi J, Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Spine-neck geometry determines NMDA receptor-dependent Ca2+ signaling in dendrites. Neuron. 2005;46(4):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmidt H, Eilers J. Spine neck geometry determines spino-dendritic cross-talk in the presence of mobile endogenous calcium binding proteins. Journal of Computational Neuroscience. 2009;27(2):229–243. doi: 10.1007/s10827-009-0139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Araya R, Jiang J, Eisenthal KB, Yuste R. The spine neck filters membrane potentials. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(47):17961–17966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608755103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koch C, Zador A, Brown TH. Dendritic spines: convergence of theory and experiment. Science. 1992;256(5059):973–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1589781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Korkotian E, Segal M. Structure-function relations in dendritic spines: is size important? Hippocampus. 2000;10(5):587–595. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:5<587::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pérez-Vega MI, Feria-Velasco A, González-Burgos I. Prefrontocortical serotonin depletion results in plastic changes of prefrontocortical pyramidal neurons, underlying a greater efficiency of short-term memory. Brain Research Bulletin. 2000;53(3):291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harris KM, Fiala JC, Ostroff L. Structural changes at dendritic spine synapses during long-term potentiation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2003;358(1432):745–748. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bourne J, Harris KM. Do thin spines learn to be mushroom spines that remember? Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17(3):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.González-Burgos I. Dendritic spine plasticity and learning/memory processes: theory, evidence and perspectives. In: Baylog LR, editor. Dendritic Spines: Biochemistry, Modeling and Properties. Huntington, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers; 2009. pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harris KM, Jensen FE, Tsao B. Three-dimensional structure of dendritic spines and synapses in rat hippocampus (CA 1) at postnatal day 15 and adult ages: implications for the maturation of synaptic physiology and long-term potentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12(7):2685–2705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02685.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kasai H, Matsuzaki M, Noguchi J, Yasumatsu N, Nakahara H. Structure-stability-function relationships of dendritic spines. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003;26(7):360–368. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GCR, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429(6993):761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Birzniece V, Sata A, Sutanto S, Ho KKY. Neuroendocrine regulation of growth hormone and androgen axes by selective estrogen receptor modulators in healthy men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(12):5443–5448. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Webber KM, Perry G, Smith MA, Casadesus G. The contribution of luteinizing hormone to Alzheimer Disease pathogenesis. Clinical Medicine and Research. 2007;5(3):177–183. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Casadesus G, Webber KM, Atwood CS, et al. Luteinizing hormone modulates cognition and amyloid-β deposition in Alzheimer APP transgenic mice. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1762(4):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]