Abstract

Babesia bovis small heat shock protein (Hsp20) is recognized by CD4+ T lymphocytes from cattle that have recovered from infection and are immune to challenge. This candidate vaccine antigen is related to a protective antigen of Toxoplasma gondii, Hsp30/bag1, and both are members of the α-crystallin family of proteins that can serve as molecular chaperones. In the present study, immunofluorescence microscopy determined that Hsp20 is expressed intracellularly in all merozoites. Importantly, Hsp20 is also expressed by tick larval stages, including sporozoites, so that natural tick-transmitted infection could boost a vaccine-induced response. The predicted amino acid sequence of Hsp20 from merozoites is completely conserved among different B. bovis strains. To define the location of CD4+ T-cell epitopes for inclusion in a multiepitope peptide or minigene vaccine construct, truncated recombinant Hsp20 proteins and overlapping peptides were tested for their ability to stimulate T cells from immune cattle. Both amino-terminal (amino acids [aa] 1 to 105) and carboxy-terminal (aa 48 to 177) regions were immunogenic for the majority of cattle in the study, stimulating strong proliferation and IFN-γ production. T-cell lines from all individuals with distinct DRB3 haplotypes responded to aa 11 to 62 of Hsp20, which contained one or more immunodominant epitopes for each animal. One epitope, DEQTGLPIKS (aa 17 to 26), was identified by T-cell clones. The presence of strain-conserved T helper cell epitopes in aa 11 to 62 of the ubiquitously expressed Hsp20 that are presented by major histocompatibility complex class II molecules represented broadly in the Holstein breed supports the inclusion of this region in vaccine constructs to be tested in cattle.

Babesiosis in cattle is caused primarily by infection with the Boophilus tick-transmitted protozoan parasites Babesia bovis and B. bigemina. While B. bigemina infection is comparatively mild, infection with B. bovis is typically acute and characterized by severe anemia, cachexia, cerebral dysfunction, and pulmonary edema (60). Cattle that do recover from B. bovis infection, either naturally or through chemotherapeutic intervention, are resistant to developing clinical disease on subsequent challenge, indicating the feasibility of achieving protective immunity against this disease by vaccination. The mechanisms of protective immunity involve both innate and adaptive immune responses (12, 25, 36). Inhibition of the growth of B. bovis in vitro is partially dependent on nitric oxide (NO) produced by gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-activated macrophages (51, 52). In addition, IFN-γ produced by Babesia-specific CD4+ T helper (Th) cells is associated with enhanced synthesis of the opsonizing immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) antibody by B lymphocytes (8). Thus, identifying B. bovis antigens and their epitopes that elicit IFN-γ-producing effector/memory CD4+ T-cell responses in immune cattle is a rational strategy for developing an effective subunit or nucleic acid vaccine against babesiosis. However, single-antigen vaccines have previously failed to provide significant protection against challenge, even though high antibody titers and strong Th1 responses were elicited (28, 44). Effective vaccines against this complex organism will probably require inclusion of multiple B- and T-lymphocyte epitopes representing different antigens and perhaps different parasite stages.

Leading candidate B. bovis antigens for vaccine development have included rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1), merozoite surface antigen 1 (MSA-1), 12D3, and spherical-body protein 1 (SBP1), formerly called Bv80 or Bb-1 (9, 12, 14, 16, 27, 28, 56, 59). Mapping of CD4+ T-cell epitopes on RAP-1, SBP-1, and 12D3 and characterization of the cytokine responses by antigen-specific Th cells were also carried out with the ultimate goal of constructing a multiepitope vaccine (14, 16, 43).

To identify additional immunostimulatory antigens, size-fractionated merozoite proteins were tested for stimulation of Th-cell responses from B. bovis-immune cattle with different genetic backgrounds (7, 12, 53). A novel 20-kDa protein was identified that stimulated recall responses from immune cattle with different major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II haplotypes, and CD4+ T-cell clones specific for this protein were also shown to express high levels of IFN-γ (13). The B. bovis 20-kDa protein is a homologue of mammalian α-crystallin and is similar to other small heat shock proteins (Hsps) identified in plants (34); it is designated Hsp20. The small Hsp/α-crystallin protein family has significant homology among species within the same genus but limited homology between genera (34). The only known related protein in protozoal parasites is Toxoplasma gondii Hsp30/bag1, which is selectively expressed by the bradyzoite stage (5). In mice, immunization with Hsp30/bag1 enhanced protective immunity against challenge (38, 42).

Although the biological function of small Hsps is not well understood, some members of the α-crystallin family function as molecular chaperones (29, 31). Consistent with a chaperonin function, B. bovis Hsp20 was reportedly expressed in an apical pattern on 5 to 10 and 100% of merozoites in two separate studies (45, 48) and was present in both membrane- and organelle-enriched and cytosolic merozoite fractions (13). Furthermore, small Hsps are highly conserved within a genus (34), and at least one B-cell epitope and one T-cell epitope from B. bovis Hsp20 (Mexico strain) were shown to be conserved among geographically distant strains of B. bovis and the Mexico strain of B. bigemina (13).

The primary goal of this study was to identify Hsp20 Th-cell epitopes recognized by immunized cattle with diverse MHC class II haplotypes to enable the selection of epitopes with a broad spectrum of recognition in the Holstein population. We show that Hsp20 is completely conserved among otherwise antigenically variant strains of B. bovis and that it contains multiple conserved T-lymphocyte epitopes. In contrast, there is little sequence identity to bovine α-crystallin. Furthermore, the Babesia antigen is expressed in both merozoite and tick larval stages, so that immunization with Hsp20 or Hsp20 epitopes could stimulate immunity against tick-transmitted sporozoites as well as blood-stage merozoites. These results identify Hsp20 as a candidate protein for inclusion in a multiepitope vaccine for babesiosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

B. bovis-infected Boophilus microplus tick larvae and induction of sporozoite development.

Uninfected and B. bovis (Mexico strain)-infected Boophilus microplus tick larvae were obtained as described previously (40). To stimulate the development of B. bovis sporozoites, infected larvae were fed on an uninfected calf for 60 h by using skin patches (17). After this period, the larvae were removed and incubated at 37°C for an additional 12 h. Uninfected larvae were obtained by using the same procedure with ticks from the same colony, except that the adult ticks were fed on an uninfected calf. Temperature and humidity conditions were the same for uninfected and infected adult ticks and larvae.

Extraction of tick larval RNA and RT-PCR analysis.

Infected Boophilus microplus larvae were homogenized in a mortar, and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA samples were treated with DNase by using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) and with the addition of RNase inhibitor (Roche). RNA was reverse transcribed and processed using a commercial reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit (One Step SuperScript RT-PCR, GIBCO BRL). For RT and predenaturation, samples were incubated at 50°C for 30 min and then at 94°C for 2 min. For PCR amplification, the forward and reverse primers for Hsp20 were 5′-ATGTCGTGTATTATGAGGTG and 5′-GGCCTTGGCGTCAATCTGAA, respectively (13). RNA and DNA from B. bovis Mo7 Mexico strain-infected erythrocytes were used as positive controls. To control for DNA contamination, the PCR amplification was performed without reverse transcriptase. RNA extracted from uninfected larvae was used as a negative control. As a control for the presence of tick RNA in the uninfected-larva samples, primers amplifying a 400-bp fragment from the Boophilus microplus Bm86 gene were used (47). Amplicons were cloned and sequenced to confirm the identity of the transcripts. The RT-PCR products were cloned into the pCR 4-TOPO plasmid vector by using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Clones were sequenced in both directions by using the Prism Ready Reaction Dye Deoxy Terminator cycle-sequencing kit and analyzed with the ABI Prism 373 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were compared with published sequences by using Nucleotide BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/).

Immunoblot analysis of Hsp20 expression in merozoites and tick larvae.

Merozoites were obtained from in vitro cultures of the Mo7 Mexico clone of B. bovis as described previously (39). Cultures containing free merozoites were centrifuged twice at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the erythrocytes and intracellular parasites. The supernatant containing free merozoites was centrifuged at 958 × g for 30 min, and the merozoites were resuspended in lysis buffer with proteinase inhibitors. Approximately 300 infected, fed larvae were ground in a mortar containing 1.5 ml of lysis buffer with proteinase inhibitors. The macerate was centrifuged at 70 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. Merozoites (4 μl) or tick larva extract (40 μl) was boiled in sample buffer containing 2% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 2.5% (wt/vol) β-mercaptoethanol and loaded on precast 10% acrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated for 1 h with a 1:500 dilution of B. bovis Hsp20-specific mouse antibody (13) in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6)-0.2% casein. Bound antibody was detected using an alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Applied Biosystems) at a 1:10,000 dilution followed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the Western-Star System reagents (Applied Biosystems). Uninfected Boophilus microplus larvae and uninfected bovine erythrocytes were used as negative control antigens.

Analysis of Hsp20 expression in merozoites by immunofluorescence.

Smears of cultured merozoites were made using Probe-On slides (Fisher), air dried for 2 h, and fixed in methanol for 5 min. The smears were rinsed in 125 mM Tris buffer containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and were blocked at 37°C for 10 min with this buffer containing 5% goat serum. B. bovis Hsp20-specific mouse serum (13) or rabbit anti-RAP-1 serum (54) was used at a final dilution of 1:100 and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The bound primary antibodies were then labeled with either fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories), and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) was added to stain the nuclear DNA. The slides were then incubated for 20 min at 37°C, blotted, and rinsed in distilled water 10 times between steps and then 3 times with a final wash for 1 min. The smears were transferred to coverslips in glycerol and DABCO (Sigma) and analyzed using confocal fluorescence microscopy. Four images of two separate smears were taken using phase contrast with sets of filters for fluorescein, rhodamine, and DAPI. As negative controls, merozoites were incubated with the two secondary antibodies only or with a mouse antiserum against recombinant Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 (MSP2) operon-associated gene 3 (OpAG3) (35) plus a rabbit antiserum against recombinant A. marginale MSP1 (39).

B. bovis strains, antigen preparation, and peptides.

For lymphocyte proliferation assays, B. bovis and B. bigemina merozoite antigens were prepared from the cultured Mexico strain by homogenization of merozoites with a French pressure cell (SLM Instruments) and ultracentrifugation to obtain a fraction enriched in cellular membranes and organelles (CM) (6). Membranes from uninfected red blood cells (URBC) were similarly prepared and used as a negative control antigen for CM. Construction and expression of recombinant B. bovis Hsp20 proteins were described previously (13). Briefly, full-length hsp20 cDNA encoding amino acids (aa) 1 to 177 or cDNAs encoding the N-terminal aa 1 to 105 (Hsp20 NT) or C-terminal aa 48 to 177 (Hsp20 CT) were cloned into the pTrcHis2 expression vector by using the pTrcHis2 TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The recombinant protein was purified on a Ni2+ column by using ProBond resin (Invitrogen) as described previously (43), dialyzed extensively against phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2), and quantified using a micro-bicinchoninic acid protein reagent kit (Pierce). Recombinant A. marginale salivary gland variant 1 (SGV1) or MSP5 proteins expressed in the same vector and purified in the same manner were used as negative control proteins for proliferation assays. Peptides spanning B. bovis Hsp20 were synthesized by Gerhardt Munske (Laboratory for Biotechnology and Bioanalysis I, Washington State University, Pullman). A peptide from A. marginale MSP2 (11) was used as a negative control peptide for proliferation assays. Recombinant proteins and peptides are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Recombinant B. bovis Hsp20 proteins and the overlapping peptides

| Protein or peptide | Amino acid position | Amino acid sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Hsp20 | 1-177 | AAK11624a |

| Hsp20 NT | 1-105 | AAK11624a |

| Hsp20 CT | 48-177 | AAK11624a |

| P1 | 11-40 | DQEVIIDEQTGLPIKSHDYSEKPSVIYKPS |

| P1-1 | 11-25 | DQEVIIDEQTGLPIKS |

| P1-2 | 23-37 | PIKSHDYSEKPSVIY |

| P2 | 26-55 | SHDYSEKPSVIYKPSTTVPQNTLLEIPPPK |

| P3 | 41-62 | TTVPQNTLLEIPPPKELENPIT |

| P4 | 53-82 | PPKELENPITFNPTVDTFFDADNNKLVLLM |

| P5 | 73-102 | ADNNKLVLLMELPGFSSTDINVECGWGELI |

| P6 | 93-122 | NVECGWGELIISGPRNKDELYEKFGNNLDI |

| P7 | 113-142 | YEKFGNNLDIHIRERKVGYFYRRFKLPNNA |

| P8 | 133-162 | YRRFKLPNNAIDKSISVGYSNGILDIRIEC |

| P9 | 153-177 | NGILDIRIECSQFSEMRRVQIDAKA |

| MSP2 P1 | NAb | MSAVSNRKLPLGGVLMALVAAVAPIHSLLA |

GenBank accession number.

NA, not applicable.

Sequence analysis of the B. bovis hsp20 gene.

The GenBank accession number for B. bovis hsp20 DNA from the Mexico strain is AF331455. PCR was used to amplify genomic hsp20 DNAs from the Australian strains G36 and vaccine strain T (kindly provided by Terry McElwain, Washington State University), Texas strain BoT24, and Argentina strains S2P and R1A by using the same primers as described for infected tick larvae. The amplicons were cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced. A BLAST search of the Swiss-Prot and GenBank databases was performed to determine sequence homology to bovine α-crystallin.

Experimental cattle.

Brahman-Angus cross cow C97 was infected with the Mexico strain of B. bovis as described previously (6) and was the source of Hsp20-specific T-cell clones (13). The class II alleles of cow C97 obtained by cloning and sequencing (43) are DRB3*3001/*4501 and DQA1*0301/*0202. The DRB3 haplotype of cow C97 determined previously by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)-PCR analysis of exon 2 is 15/34. Four Holstein steer calves aged 5 to 6 months and weighing 200 to 250 kg were also typed for MHC class II DRB3 by RFLP-PCR analysis of exon 2 (58). The nomenclature of the alleles is described on the bovine leukocyte antigen (BoLA) nomenclature website (http://www2.ri.bbsrc.ac.uk.bola/). This analysis revealed that the calves have heterozygous and distinct DRB3 haplotypes, as shown in Table 2 (see below). The calves received four subcutaneous inoculations, at 3-week intervals, of 20 μg of recombinant Hsp20 emulsified in 1 ml of RIBI adjuvant (catalog no. R-730; RIBI Immunochem Research, Inc., Hamilton Mont., now Corixa, Seattle, Wash.) consisting of monophosphoryl lipid A, trehalose dimycolate, and cell wall skeleton. For the first immunization, 10 μg (0.5 ml) of human interleukin-12 IL-12 (kindly provided by Genetics Institute, Cambridge, Mass.) was also inoculated into the same injection site immediately after the recombinant Hsp20. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and serum samples were collected before each immunization for analysis of lymphocyte proliferation and antigen-specific antibody production.

TABLE 2.

Proliferative responses of CD4+ T-cell lines from B. bovis Hsp20-immunized calves to B. bovis and B. bigemina

| Antigen | Proliferation (cpm) of short-term T-cell linesa from calfb:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 (8/1) | 56 (10/7) | 57 (22/11) | 58 (24/12) | |

| Medium | 1,576 ± 210 | 1,666 ± 867 | 463 ± 128 | 113 ± 10 |

| URBC | 953 ± 136 | 1,465 ± 82 | 436 ± 139 | 95 ± 17 |

| B. bovis CM | 62,952 ± 658 | 32,215 ± 1,195 | 11,942 ± 1,094 | 24,922 ± 1,024 |

| B. bigemina CM | 60,068 ± 1,285 | 27,339 ± 1,683 | 10,987 ± 758 | 22,854 ± 1,073 |

Short term T-cell lines were established by stimulation with B. bovis CM for 1 week and resting for 1 week. Lymphocytes were cultured for 3 days with 25 μg of the indicated antigens per ml, radiolabeled, and counted. Results are expressed as the mean counts per minute (cpm) of [3H]thymidine incorporation ± 1 SD. Significant proliferation is indicated in bold type.

DRB3 haplotypes determined by RFLP-PCR are indicated for each calf.

T-lymphocyte cell lines and proliferation assays.

Generation and culture of Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones from B. bovis-infected immune cow C97 have been described previously (13). Short-term T-cell lines were established from cow C97 and Hsp20-immunized calves by stimulating 4 × 106 PBMC in 24-well plates (Costar) containing 1.5 ml of complete RPMI 1640 medium (6) with 10 μg of B. bovis CM antigen per ml for 1 week and resting them without antigen for 1 week before use unless indicated otherwise (13). T-cell proliferation assays were performed for 3 days in duplicate or triplicate wells of round-bottom 96-well plates at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Then 3 × 104 T cells and 2 × 105 irradiated PBMC as a source of autologous antigen-presenting cells (APC) per well were assayed with 0.1 to 25 μg of various antigens per ml in a total volume of 100 μl of complete RPMI 1640 medium. Proliferative responses were measured by radiolabeling cells with 0.25 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Dupont New England Nuclear) for the last 18 h of culture.

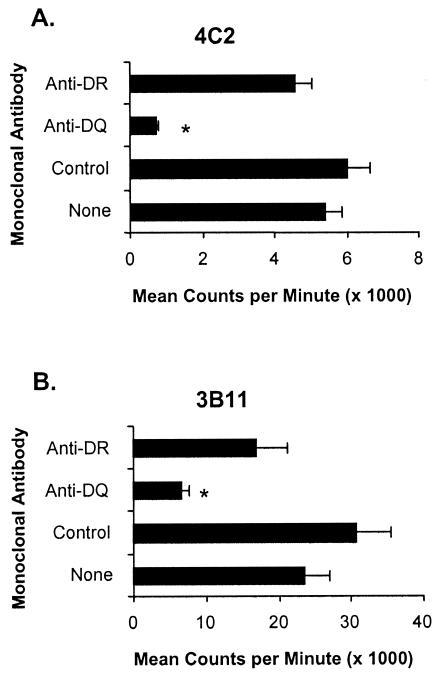

To determine if antigen recognition by the CD4+ T-cell clones was restricted by DRB3 or DQ molecules, 2 × 105 autologous APC were incubated in 96-well plates for 1 h with 4 μg of either monoclonal antibody (MAb) ILA-21 (anti-DR); (18) or MAb TH22A (anti-DQ) (20) per ml prior to the addition of T cells. Isotype-matched control IgG2a MAb Colis205 was used as a negative control. All MAbs were obtained from Washington State University Monoclonal Antibody Center and purified by affinity chromatography to protein G by using an Equilibrate Hi Trap Protein G column (Pharmacia Biotech) as recommended by the manufacturer. Student's one-tailed t test was used to determine the statistical significance of levels of T-cell proliferation by using different antigens or MAb.

IFN-γ ELISA.

Supernatants (50 μl) were collected from triplicate wells of proliferation assay mixtures and pooled before being labeled with [3H]thymidine. The level of IFN-γ in the supernatants diluted 1:4 to 1:20 was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BOVIGAM; CSL Ltd., Parkville, Victoria, Australia) and compared with a standard curve obtained with a supernatant from a Mycobacterium bovis purified protein derivative-specific Th-lymphocyte clone that contained 440 U of IFN-γ/ml (previously determined by the neutralization of vesicular stomatitis virus) (8). In the assay, 1 U corresponds to approximately 1.7 ng of IFN-γ (4).

Sequence analysis of T-cell receptor α and β chains.

Sequencing of the T-cell receptor α (TCR-α and TCR-β chains of Hsp20-specific Th-cell clones was performed as described previously (22). Briefly, Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones were cultured for 7 days with antigen and APC as described previously (13), washed, and then cultured for 1 week with complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% T-cell growth factor without antigen or APC to expand the CD4+ T cells and to eliminate contamination with RNA derived from APC. Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent. The first-strand DNA was synthesized from 1 to 3 μg of total RNA by using oligo(dT) and was precipitated with spermine. The pellet was resuspended with 68 μl of H2O, and a poly(dG) tail sequence was introduced in a 100-μl reaction mixture containing 1 mM dGTP (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), 30 U of deoxynucleotidyltransferase (TdT) (Invitrogen), and 5× TdT buffer (Invitrogen) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. To amplify the TCR cDNAs, PCR was performed using a mixture of the ANpolyC primer (5′-GCATGCGCGCGGCCGCGGAGGCCCCCCCCCCCCCC-3′) and the AN primer (5′-GCATGCGCGCGGCCGCGGAGGCC-3′) at a ratio of 1:9 as a forward primer and 5′-GAGCCGCAGCGTCATGAGCAGATTA-3′ or 5′-AGCACAGCGTACAGGGTGGCCTTCC-3′, for α and β chains, respectively, as reverse primers. The first five cycles of amplification involved annealing at 50°C, and the subsequent 30 cycles involved annealing at 55°C. The amplicons were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

RESULTS

Conservation of Hsp20 among strains of B. bovis.

Previous studies using proliferation assays with T-cell clones and immunoblotting with either MAb 23/28.57 (45), which was subsequently found to recognize Hsp20, or an Hsp20 peptide-specific mouse serum revealed conservation of B. bovis Hsp20 epitopes among strains from several different geographical locations (13). To determine the level of amino acid sequence conservation in the full-length proteins, hsp20 genomic DNA obtained from several parasite strains was sequenced. The predicted amino acid sequences of the encoded mature proteins were identical in parasite strains from Mexico, Texas, Argentina, and Australia (data not shown). When the B. bovis hsp20 sequence was used to BLAST search the Swiss-Prot and GenBank databases, the best matched bovine protein was αA-crystallin (accession no. P02470). As described previously for the α-crystallin family of proteins (13), there was a significant sequence alignment of Hsp20 with bovine αA-crystallin in the C-region, consisting of 25% identity of the 89 aa compared in this region and the conserved GXLXXXXP motif (reference 13 and data not shown). However, this amino acid identity was scattered throughout the sequence and did not comprise blocks of identical sequence (data not shown).

Cellular localization of B. bovis Hsp20 in merozoites and expression in larval tick stages.

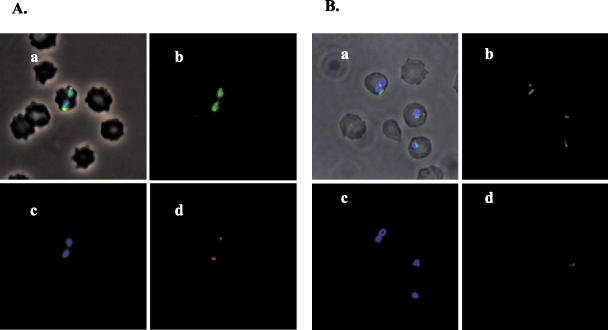

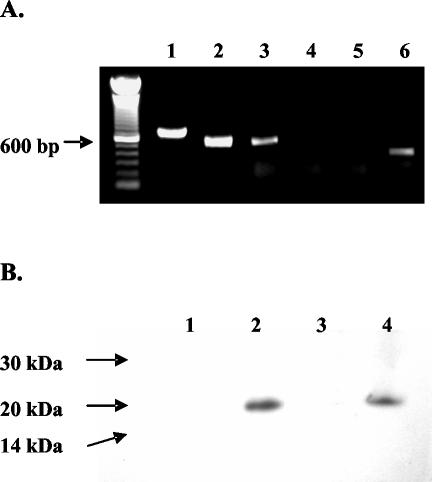

Conflicting results on the percentage of merozoites that expressed Hsp20 (45, 48) led us to compare the expression of this protein with that of surface-exposed proteins MSA-1 and RAP-1 by using a multicolor confocal immunofluorescence technique (39). In contrast to MSA-1 and RAP-1, Hsp20 was never visualized on the surface of live merozoites (data not shown). However, in fixed merozoites, Hsp20 was expressed in 100% of the parasites, exhibiting diffuse fluorescence (Fig. 1A, panel b) that also colocalized with RAP-1 in the apical complex (panels a and d). In parasites that resembled the trophozoite stage, characterized by a larger size and a single intraerythrocytic organism, Hsp20 was visualized as one or two bands traversing the parasite (Fig. 1B, panels a and b). Labeling was not observed when parasites were incubated with a combination of a mouse antiserum against A. marginale MSP2 OpAG3 plus rabbit antiserum against recombinant A. marginale MSP1 (data not shown). Analysis of Hsp20 expression by RT-PCR (Fig. 2A) and immunoblotting (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that Hsp20 transcripts and protein are expressed in tick larval stages as well as blood-stage merozoites. Similar studies performed with B. bigemina have also confirmed the expression of Hsp20 in sporozoites (J. Mosqueda, unpublished observations).

FIG. 1.

Localization of B. bovis Hsp20 protein in B. bovis merozoites by using immunofluorescence microscopy. Smears of B. bovis-infected erythrocytes were incubated with mouse anti-B. bovis Hsp20 peptide-specific antiserum and rabbit anti-RAP-1 serum. The bound primary antibodies were then labeled with secondary antibodies, a goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC (green) and a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with rhodamine (red). To visualize the nuclei, DNA was labeled with DAPI (blue). (A) Merozoites; (B) trophozoites. Each image was recorded under phase contrast with the following fluorescence channels: FITC (b), DAPI (c), rhodamine (d), and combined channels for all three stains (a).

FIG. 2.

Expression of B. bovis Hsp20 in Boophilus microplus tick larvae. (A) B. bovis hsp20 transcripts were amplified by RT-PCR from B. bovis merozoites (lane 2), B. bovis-infected larvae (lane 3), B. bovis-infected larvae without RT (lane 4), and uninfected larvae (lane 5). Larva-derived bm86 transcript was also amplified by RT-PCR from the same sample of uninfected larvae (lane 6). As a positive control, B. bovis hsp20, which contains a 119-bp intron, was amplified from genomic DNA by PCR (lane 1). (B) Immunoblot analysis of B. bovis Hsp20 in the following antigens at approximately 10 μg of protein per lane: URBC (lane 1), B. bovis CM (lane 2), uninfected tick larvae (lane 3), and B. bovis-infected tick larvae (lane 4). B. bovis Hsp20 was detected with a 1:200 dilution of mouse anti-B. bovis Hsp20 peptide-specific antiserum.

CD4+ T-lymphocyte responses in Hsp20-immunized calves.

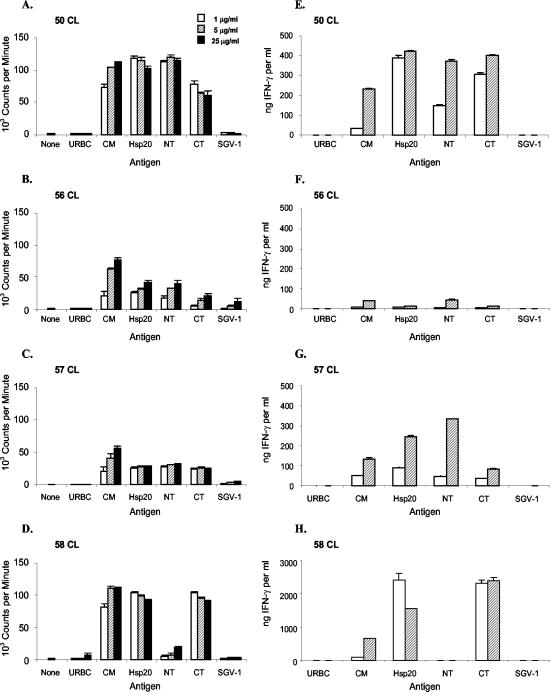

Previous studies demonstrated recognition of B. bovis Hsp20 by cattle that had recovered from B. bovis infection (13). To identify B. bovis Hsp20 CD4+ T-cell epitopes for cattle with different genetic backgrounds, four calves with completely different DRB3 haplotypes were immunized with recombinant B. bovis Hsp20 and short-term T-cell lines were tested with different antigens and overlapping peptides shown in Table 1. All four calves responded to Hsp20, B. bovis, and B. bigemina CM antigens, demonstrating recognition of epitopes on the native B. bovis Hsp20 that are conserved in B. bigemina (Table 2). Furthermore, all vaccinated calves responded to both the N-terminal and C-terminal regions, and animal 58 preferentially responded to the C-terminal region (Fig. 3A to D). IFN-γ production by antigen-stimulated T-cell lines mirrored that of proliferation and reached high levels in three animals (Fig. 3E to H). Using overlapping peptides spanning aa 11 to 177, we found that each peptide stimulated the proliferation of T cells from at least one animal and that peptide P2 was recognized by all four calves (Table 3). Peptide P1 also stimulated T-cell lines from three calves. Based on peptide recognition, at least four T-cell epitopes were recognized by three calves and at least two epitopes were recognized by the other calf. The P2 peptide has at least one T-cell epitope recognized by all calves (Table 3). These results show that Hsp20 has multiple T-cell epitopes, and that the region of aa 11 to 62, represented by overlapping peptides P1 to P3, stimulates cells from cattle with four different MHC class II haplotypes.

FIG. 3.

Proliferative responses and IFN-γ production by T-cell lines from Hsp20-immunized calves. Short-term T-cell lines from calves 50 (A and E), 56 (B and F), 57 (C and G), and 58 (D and H) were stimulated with 1 (white bars), 5 (striped bars), or 25 (black bars) μg of URBC, B. bovis CM, B. bigemina CM, recombinant B. bovis Hsp20 (full length, aa 1 to 177), Hsp20 NT (aa 1 to 105), and Hsp20 CT (aa 48 to 177) antigens per ml, and proliferation (A to D) and IFN-γ production (E to H) were determined. Recombinant A. marginale SGV-1 protein expressed in the same vector was used as a negative control antigen. Results are presented as the mean counts per minute + 1 standard deviation (SD) of triplicate cultures of T cells stimulated with antigen for 3 days. To measure IFN-γ production, supernatants (50 μl) were collected from triplicate wells of the proliferation assay mixture before being labeled. IFN-γ production was measured in pooled supernatants by ELISA, and the results are expressed as mean nanograms per milliliter + 1 SD of duplicate wells in the ELISA.

TABLE 3.

Proliferative responses of CD4+ T-cell lines from B. bovis Hsp20-immunized calves to Hsp20 peptides

| Peptide | Proliferation (SI) by T-cell lines from calfa:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 56 | 57 | 58 | |

| P1 | 103.1 | 1.7 | 52.9 | 4.1 |

| P2 | 108.0 | 50.6 | 57.9 | 8.7 |

| P3 | 117.0 | 1.1 | 78.8 | 27.1 |

| P4 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

| P5 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 14.7 | 1.3 |

| P6 | 104.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 5.1 |

| P7 | 65.3 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 145.7 |

| P8 | 6.5 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 2.4 |

| P9 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 68.1 |

PBMC were stimulated for 1 week with B. bovis CM and rested for 1 week before being tested. Results were obtained for the optimal response to 1 or 10 μg of each peptide per ml. SI indicates stimulation indices (mean counts per minute of the response to Hsp20 peptide/mean of the response to control A. marginale MSP2 peptide). Significant responses (SI ≥ 3.0) are indicated in bold type. These responses were significant when individual counts per minute were compared by the one-tailed Student t test (P < 0.005).

CD4+ T-cell epitope mapping on B. bovis Hsp20 with Th-cell clones.

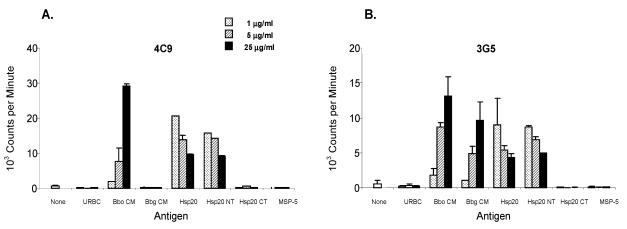

It was also of interest to identify epitopes recognized by Hsp20-specific T cells from infected animals. T-cell lines from B. bovis-infected and immune cow C97, that responded strongly to Hsp20 (13), were tested for lymphocyte proliferation in response to recombinant full-length Hsp20, the N-terminal region of Hsp20, and the C-terminal region of Hsp20. In three assays, independently derived T-cell lines from this animal responded only to the N-terminal region of Hsp20 but not to the C-terminal region, suggesting that the epitope(s) resided between aa 1 and 47 (Table 4). To further define these, overlapping peptides P1 to P3 spanning aa 11 to 62 were tested with the cell lines, and only peptide P1 (aa 11 to 40) stimulated a proliferative response (Table 4). Finally, peptides P1-1 and P1-2, which spanned peptide P1, were tested, and only peptide P1-1 (aa 11 to 25) was stimulatory for the cell lines (Table 4). To further define the epitope(s) recognized by animal C97, four CD4+ T-cell clones specific for B. bovis Hsp20, previously shown to proliferate and produce IFN-γ on stimulation with both soluble cytosolic and CM antigens of B. bovis (13; W. C. Brown, unpublished observations), were also tested with recombinant proteins and peptides. All T-cell clones responded to B. bovis CM, Hsp20, and Hsp20 NT antigen (aa 1 to 105) but not Hsp20 CT antigen (aa 48 to 177), suggesting that the epitope(s) is located between aa 1 and 47 (Fig. 4). Interestingly, clones 4C2 and 4C9 did not recognize B. bigemina CM whereas clones 3B11 and 3G5 did recognize B. bigemina CM (representative clones are shown in Fig. 4A and 4B, respectively). Using synthetic peptides listed in Tables 1 and 5, we mapped the minimal epitopes recognized by these T-cell clones to a 10-amino acid sequence, DEQTGLPIKS. Deletion of either the N-terminal aspartic acid residue or the C-terminal serine residue abolished proliferation, confirming that this was the minimal sequence required for the T-cell response (Table 5). To explain the differential response to B. bigemina by the two sets of T-cell clones, clones were tested with the homologous peptide derived from B. bigemina Hsp20, DEQTGLPVKN (BbgP1-4) (Table 5, experiment 2). As expected, clones 4C2 and 4C9 responded only to B. bovis-derived peptide (BboP1-4), while clones 3B11 and 3G5 responded to both B. bovis- and bigemina-derived peptides. Two amino acid residues at positions 8 and 10 of the peptide derived from B. bovis differ from those at the same positions in the peptide from B. bigemina (boldface type in amino acid sequences). To determine which amino acid substitution was critical for loss of recognition by clones 4C2 and 4C9, two other altered peptides, P1-4N and P1-4V, were tested (Table 5, experiment 2). Clones 4C2 and 4C9 were unable to recognize the peptide if the isoleucine residue at position 8 was replaced by a valine residue, whereas the response was still present when the serine residue at position 10 was replaced by an asparagine residue. As expected, clones 3B11 and 3G5 still responded to peptides with these substitutions at either position 8 or position 10.

TABLE 4.

Proliferative responses of CD4+ T cells from B. bovis-infected immune cow C97 to protein antigens

| Antigen | Proliferation (cpm) of T cellsa |

|---|---|

| Native protein | |

| URBC | 211 ± 101 |

| B. bovis CM | 79,270 ± 1,184 |

| Recombinant protein | |

| Hsp20 | 74,009 ± 2,261 |

| Hsp20 NT | 85,673 ± 10,169 |

| Hsp20 CT | 476 ± 119 |

| MSP5 | 163 ± 23 |

| Peptide | |

| P1 | 82,691 ± 665 |

| P2 | 177 ± 31 |

| P3 | 224 ± 41 |

| P1-1 | 85,689 ± 5,222 |

| P1-2 | 292 ± 96 |

| P MSP2 | 100 ± 7 |

Cell lines were established by stimulation with B. bovis CM for 1 week, resting for 1 week, stimulation with Hsp20 for 1 week, and resting for 1 week. Lymphocytes were cultured for 3 days with 25 μg of native or recombinant protein per ml and 10 μg of peptide per ml, radiolabeled, and counted. Results are expressed as the mean counts per minute (cpm) of [3H]thymidine incorporation ± 1 SD. Significant proliferation is indicated in bold type.

FIG. 4.

Proliferative response of B. bovis Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones. Clones 4C9 (A) and 3G5 (B) were stimulated with 1 (stippled bars), 5 (striped bars), or 25 (black bars) μg of URBC, B. bovis CM, B. bigemina CM, recombinant B. bovis Hsp20 (full length, aa 1 to 177), Hsp20 NT (aa 1 to 105), Hsp20 CT (aa 48 to 177), and control A. marginale MSP-5 antigens per ml. Results are presented as the mean counts per minute + 1 SD of duplicate cultures of T cells stimulated with antigen for 3 days.

TABLE 5.

Identification of the minimal CD4+ T-cell epitope recognized by C97 Th-cell clones

| Peptide | Amino acid sequencea | SIe

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 4C9f | 3G5f | ||

| Expt 1 | |||

| P1 | DQEVIIDEQTGLPIKSHDYSEKPSVIYKPS | 20.7 | 51.8 |

| P1-1 | DQEVIIDEQTGLPIKS | 31.2 | 52.9 |

| P1-2 | PIKSHDYSEKPSVIY | 1.4 | 1.1 |

| P1-3 | EQTGLPIKS | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| P1-4 | DEQTGLPIKS | 5.4 | 18.5 |

| P1-5 | IDEQTGLPIKS | 25.5 | 37.6 |

| P1-5ΔS | IDEQTGLPIK | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| P1-5ΔKS | IDEQTGLPI | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Expt 2 | |||

| BboP1-4 | DEQTGLPIKS | 10.3 | 34.8 |

| BbgP1-4b | DEQTGLPVKN | 0.8 | 15.0 |

| P1-4Nc | DEQTGLPIKN | 5.7 | 18.3 |

| P1-4Vd | DEQTGLPVKS | 0.8 | 41.2 |

The minimal T-cell epitope that stimulated CD4+ T cell clones is underlined.

Amino acid sequence of B. bigemina Hsp20 corresponding to P1-4. Amino acid residues in bold type indicate differences between the B. bovis and B. bigemina Hsp20 epitopes.

Replacement of the serine residue with an asparagine residue (bold type).

Replacement of the isoleucine residue with a valine residue (bold type).

SI, stimulation index (mean counts per minute of cells stimulated with 1 μg of Hsp20 peptide per ml/mean counts per minute of control MSP2 peptide). SI values of >3.0 are considered positive and are shown in bold type.

Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones described previously (13).

The finding that the two sets of T-cell clones recognize the same epitope on B. bovis Hsp20 with different fine specificities suggested that either different MHC class II molecules presented the peptides to the respective pairs of clones or that TCR usage by the clones may be different. To attempt to determine whether different MHC molecules are involved in presenting the epitope, blocking studies using anti-DR and anti-DQ MAbs were performed. However, all clones were apparently restricted by the DQ molecule (Fig. 5 and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

MHC DQ restriction of Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones. T-cell clones 4C2 (A) and 3B11 (B) were stimulated with 10 μg of B. bovis CM per ml and autologous APC that were precultured for 1 h with no MAb (none) or with 4 μg of MAb specific for DRα, MAb specific for DQα, or isotype-matched MAb Colis205D (control) per ml for 3 days. Results are presented as the mean counts per minute + 1 SD of duplicate cultures of T cells stimulated with antigen. Asterisks indicate that the response is significantly lower than the response in the presence of isotype control MAb (P < 0.05). Results are representative of at least two experiments performed with each clone.

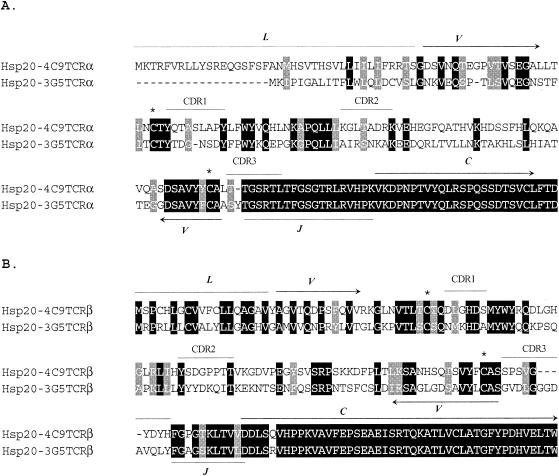

TCR-α and TCR-β chain sequences used by CD4+ T-cell clones.

Because we could not determine whether different class II molecules presented the epitope to the different T-cell clones, the TCR-α and TCR-β chains from clones 4C2, 4C9, 3B11, and 3G5 were sequenced. Clones 4C2 and 4C9 had identical sequences in both the α and β chains throughout variable (V), diversity (D), joining (J), and constant (C) regions, suggesting that these two clones were originally derived from the same cell (data not shown). Similarly, clones 3B11 and 3G5 also had completely identical TCR-α and TCR-β chains, indicating that these two clones also originated from the same cell (data not shown). However, the TCR-α and TCR-β chain sequences differed between the pairs of clones (clones 3G5 and 4C9 are shown in Fig. 6). Interestingly, in spite of their similar responses to the same minimal epitope, the TCR sequences of clones 3G5 and 4C9 did not have strong identity in their V region of either the α or β chain (32.6 and 34.8% identity, respectively). However, these clones use the same J segment in the α chain, and so a large part of complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) is identical, consistent with CDR3 of the TCR-α chain playing a major role in determining epitope specificity. In contrast, the β-chain CDRs did not have appreciable sequence similarity and the CDR3s were of different lengths, which may explain the different epitope fine specificities of the two sets of clones.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of the TCR-α and TCR-β chain sequences between B. bovis Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones with different fine specificities. The amino acid sequence alignment of TCR-α chains (A) and TCR-β chains (B) from clones 4C9 and 3G5 is shown. Leader (L), variable (V), joining (J), constant (C), and CDR1-3 regions are indicated by arrows or bars. The diversity (D) region is not indicated because of the ambiguous boundary. Boundaries of L, V, J, and C regions and CDRs were predicted based on data from references 2, 30, and 55. Conserved cysteine residues in the V region are indicated by asterisks.

DISCUSSION

We have focused on discovering B. bovis antigens and their epitopes that elicit a type 1 memory CD4+ T-cell response in protected cattle as potential candidates for inclusion in a multiepitope vaccine construct (12). B. bovis Hsp20 was identified as an immunostimulatory antigen present in low-molecular-weight protein fractions of merozoites that induced proliferation and IFN-γ production by B. bovis-specific T-cell lines and clones (7, 13, 53). The present study has determined that Hsp20 is an intracellular protein that is diffusely expressed in the merozoite and associated with the apical complex and has additionally demonstrated the expression of B. bovis Hsp20 in tick stages. Furthermore, a homologue of Hsp20 is present in B. bigemina (13) and there is complete amino acid sequence conservation of Hsp20 among B. bovis strains. This would indicate the likelihood of inducing a cross-reactive immune response. The sequence conservation and ubiquitous expression of Hsp20 in merozoite and tick larval stages indicate the potential use of this protein in a vaccine construct that would stimulate immunity against sporozoites and merozoites and provided the rationale for identification of CD4+ T-cell epitopes recognized by cattle with a diverse repertoire of MHC class II haplotypes. Although there was homology to bovine αA-crystallin, including conservation of an α-crystallin signature motif in the C-region, the amino acid identity was limited to amino acids scattered throughout the sequence in this region and there were no blocks of identical sequence. Therefore, it is unlikely that immunization with Hsp20 would stimulate a cross-reactive response to the bovine αA-crystallin.

The ubiquitous expression and intracellular localization of Hsp20 are consistent with its potential role as a molecular chaperone. In some parasites that resembled trophozoites, Hsp20 was visualized as one or two bands traversing the parasite. Although this staining pattern resembles that of microtubules (3), further analysis is required to confirm such an association. The colocalization of Hsp20 with RAP-1 in the merozoite apical complex is also consistent with a previously reported polar pattern of expression by indirect immunofluorescence analysis using Hsp20-specific MAb 23/28.57 (45). We also detected Hsp20 in CM and soluble cytosolic fractions by T-cell proliferation and immunoblotting assays (13; also see above). In other organisms, small Hsps are soluble and can function as molecular chaperones in cases where association with other proteins acts to stabilize them and permit correct folding (31).

CD4+ T-cell lines from immunized calves responded with comparable levels of proliferation when recombinant Hsp20 and native B. bovis antigens were compared. This indicates that processing and epitope presentation of the native and recombinant antigens are similar and that immunization with recombinant Hsp20 elicits a population of memory T cells that could be activated on infection. Moreover, high levels of IFN-γ were produced ex vivo by three calves in response to these proteins, possibly as a result of using IL-12 as an adjuvant (57, 61).

The most immunostimulatory region of B. bovis Hsp20 for Th cells from the cattle used in this study is the N-terminal region spanning aa 11 to 62. This region contains one or more epitopes that stimulated T cells from all five cattle in the study, and at least two epitopes are present which stimulated T cells from three calves. Based on the frequencies of DRB3 alleles in Holstein cattle (50; H. A. Lewin, unpublished observations) and their association with DQ alleles due to strong linkage phase disequilibrium (1), it is estimated that at least 70% of Holstein or Friesian cattle in a given herd would have at least one of the DRB3-DQ haplotypes evaluated in this study. Therefore, aa 11 to 62 of Hsp20 should be broadly recognized by these breeds and may be useful in a multiepitope vaccine construct against B. bovis.

Four B. bovis Hsp20-specific CD4+ T-cell clones from immune cow C97 recognized a minimal epitope in peptide P1 (aa 11 to 40), consisting of 10 aa, DEQTGLPIKS (peptide BboP1-4). Interestingly, further analyses revealed that two of these clones (3B11 and 3G5), but not clones 4C2 and 4C9, also recognized B. bigemina Hsp20 protein and its corresponding peptide, DEQTGLPVKN (BbgP1-4), which has amino acid changes at positions 8 and 10 (shown in bold type). The isoleucine residue at position 8 is critical for recognition by the B. bovis Hsp20-specific clones 4C2 and 4C9. None of the clones responded to 9-mers consisting of either DEQTGLPIK or EQTGLPIKS. However, replacement of the serine residue at position 10 of BboP1-4 with an asparagine residue was tolerated by all four clones, indicating that the amino acid at position 10 does not determine antigen specificity per se but may play a role in stabilizing peptide binding. Together, these results indicate that the aspartic acid residue at position 1 is the first MHC class II anchor residue and the serine residue at position 10 lies outside of the MHC anchor residues in this epitope. Flanking as well as anchor residues are important for immunogenicity, since in certain MHC haplotypes Th-cell epitopes can be modulated by altering the amino acids flanking the minimal core determinant (15, 41).

The TCRs of the two sets of T-cell clones were sequenced to clarify how the amino acid differences in the C terminus of minimal epitopes BboP1-4 and BbgP1-4 were recognized. Clone pairs 4C2/4C9 and 3B11/3G5 use different V segments with little similarity in the CDR1 and CDR2 regions of either the α or β chain. However, the finding that the main similarity in the TCR CDRs is within the α-chain CDR3 contributed by the J region suggests that this region plays a major role in determining the shared specificity against the conserved N terminus of the minimal P1-4 epitopes in B. bovis and bigemina Hsp20. In support of this, analysis of the crystal structure of the TCR-peptide-MHC class II complex has demonstrated that recognition of the N-terminal part of an antigenic peptide is dominated by the TCR Vα domain (49). On the other hand, sequence differences in the other regions of the TCRs, specifically in the length of the β-chain CDR3, are probably responsible for the different recognition patterns of the two sets of clones (19, 37). Although the epitope-specific response by both sets of clones is apparently restricted by a DQ molecule, it is possible that different DQ molecules present the BboP1-4 and BbgP1-4 epitopes, since these T-cell clones were derived from a cow with heterozygous DQ alleles. Furthermore, cross-haplotype pairing of the DQ α and β chains can occur, increasing the number of functional DQ heterodimers that can present antigen (10, 24).

Induction of protective immunity against intraerythrocytic protozoan parasites by immunization has been extensively studied and has proven to be challenging (26). We and others have found that use of a single vaccine antigen, such as the highly immunogenic B. bovis RAP-1 or MSA-1 protein, is not sufficient for stimulating protective immunity against B. bovis infection (28, 45). On the other hand, multiepitope vaccines have been shown to induce a protective level of specific antibody and cellular immunity against experimental models of malaria and to stimulate T-lymphocyte responses in Plasmodium falciparum-vaccinated or exposed humans (21, 23, 32, 33, 46). As we have demonstrated in the present and recent studies, B. bovis Hsp20 is conserved among B. bovis strains and B. bigemina and is immunogenic for T cells in cattle with different genetic backgrounds. The present study provides new information on the immunogenic epitopes of B. bovis Hsp20 that are recognized broadly in the Holstein breed and that can be used in designing a multiepitope vaccine against highly pathogenic B. bovis strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Kegerreis, Shelley Whidbee, Deb Alperin, and Emma Karel for excellent technical assistance; Colleen Olmstead for BoLA DRB3 typing; Steve Hines and Will Goff for providing B. bovis parasites; Terry McElwain and Shawn Berens for providing B. bovis DNA samples; Lance Perryman for providing hybridoma cells producing MAb 23/28.57; and Genetics Institute for providing human IL-12.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-A130136.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amills, M., V. Ramiya, J. Norimine, and H. A. Lewin. 1998. The major histocompatibility complex of ruminants. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epizoot. 1:108-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arden, B., S. P. Clark, D. Kabelitz, and T. W. Mak. 1995. Human T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics 42:455-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bannister, L. H., J. M. Hopkins, R. E. Fowler, S. Krishna, and G. H. Mitchell. 2000. A brief illustrated guide to the ultrastructure of Plasmodium falciparum asexual blood stages. Immunol. Today 16:427-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer, J. C., R. W. Stich, W. C. Brown, and W. P. Cheevers. 1998. Cloning and expression of caprine interferon-gamma. Gene 210:103-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohne, W., U. Gross, D. J. P. Ferguson, and J. Heesemann. 1995. Cloning and characterization of a bradyzoite-specifically expressed gene (hsp30/bag1) of Toxoplasma gondii, related to genes encoding small heat-shock proteins of plants. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1221-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, W. C., K. S. Logan, G. G. Wagner, and C. L. Tetzlaff. 1991. Cell-mediated immune responses to Babesia bovis antigens in cattle following infection with tick-derived or cultured parasites. Infect. Immun. 59:2418-2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, W. C., K. S. Logan, S. Zhao, D. K. Bergman, and A. C. Rice-Ficht. 1995. Identification of Babesia bovis merozoite antigens separated by continuous-flow electrophoresis that stimulate proliferation of helper T cell clones derived from B. bovis-immune cattle. Infect. Immun. 63:106-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, W. C., T. F. McElwain, G. H. Palmer, S. E. Chantler, and D. M. Estes. 1999. Bovine CD4+ T-lymphocyte clones specific for rhoptry-associated protein-1 (RAP-1) of Babesia bigemina stimulate enhanced immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2 synthesis. Infect. Immun. 67:155-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, W. C., T. F. McElwain, B. J. Ruef, C. E. Suarez, V. Shkap, C. G. Chitko-McKown, A. C. Rice-Ficht, and G. H. Palmer. 1996. Babesia bovis rhoptry-associated protein-1 is immunodominant for T helper cells of immune cattle and contains T cell epitopes conserved among geographically distant B. bovis strains. Infect. Immun. 64:3341-3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown, W. C., T. C. McGuire, W. Mwangi, K. A. Kegerreis, H. Macmillan, H. A. Lewin, and G. H. Palmer. 2002. Major histocompatibility complex class II DR-restricted memory CD4+ T lymphocytes recognize conserved immunodominant epitopes of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 1a. Infect. Immun. 70:5521-5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, W. C., T. C. McGuire, D. Zhu, H. A. Lewin, J. Sosnow, and G. H. Palmer. 2001. Highly conserved regions of the immunodominant major surface protein 2 (MSP2) of the ehrlichial pathogen Anaplasma marginale are rich in naturally derived CD4+ T lymphocyte epitopes that elicit strong recall responses. J. Immunol. 166:1114-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, W. C., and G. H. Palmer. 1999. Designing blood stage-stage-vaccines against Babesia bovis and B. bigemina. Parasitol. Today 15:275-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown, W. C., B. J. Ruef, J. Norimine, K. A. Kegerreis, C. E. Suarez, P. G. Conley, R. W. Stich, K. H. Carson, and A. C. Rice-Ficht. 2001. A novel 20-kilodalton protein conserved in Babesia bovis and B. bigemina stimulates memory CD4+ T lymphocyte responses in B. bovis-immune cattle. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119:97-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown, W. C., S. Zhao, V. M. Woods, C. A. Tripp, C. L. Tetzlaff, V. T. Heussler, D. A. Dobbelaere, and A. C. Rice-Ficht. 1993. Identification of two Th1 cell epitopes on the Babesia bovis-encoded 77-kilodalton merozoite protein (Bb-1) by use of truncated recombinant fusion proteins. Infect. Immun. 61:236-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson, R. T., K. M. Vignali, D. L. Woodland, and D. A. A. Vignali. 1997. T cell receptor recognition of MHC class II-bound peptide flanking residues enchances immunogenicity and results in altered TCR V region usage. Immunity 7:387-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Court, R. A. K. Sitte, J. P. Opdebeeck, and I. A. East. 1998. Mapping T cell epitopes of Babesia bovis antigen 12D3: implications for vaccine design. Parasite Immunol. 10:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dagliesh, R. J., and N. P. Stewart. 1982. Some effects of time, temperature and feeding on infection rates with Babesia bovis and Babesia bigemina in Boophilus microplus larvae. Int. J. Parasitol. 12:323-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies, C. J., I. Joosten, D. L. Andersson, M. A. Arriens, D. Bernoco, B. Bissumbhar, G. Byrns, M. J. T. van Eijk, B. Kristensen, H. A. Lewin, S. Mikko, A. L. G. Morgan, N. E. Muggli-Cockett, P. R. Nilsson, R. A. Oliver, C. A. Park, J. J. van der Poel, M. Polli, R. L. Spooner, and J. A. Stewart. 1994. Polymorphism of bovine MHC class II genes. Joint report of the Fifth International Bovine Lymphocyte Antigen (BoLA) Workshop. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 21:259-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis, M. M., and M. G. McHeyzer-Williams. 1995. Antigen-specific development of primary and memory T cells in vivo. Science 268:106-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutia, B. M., L. MacCarthy-Morrough, E. J. Glass, R. L. Spooner, and J. Hopkins. 1995. Discrimination between major histocompatibility complex class II DQ and DR locus products in cattle. Anim. Genet. 26:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doolan, D. L., S. L. Hoffman, S. Southwood, P. A. Wentworth, J. Sidney, R. W. Chesnut, E. Keough, E. Appella, T. B. Nutman, A. A. Lal, D. M. Gordon, A. Oloo, and A. Sette. 1997. Degenerate cytotoxic T cell epitopes from P. falciparum restricted by multiple HLA-A and HLB-B supertype alleles. Immunity 7:97-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elwyn, Y. L., J. F. Elliott, S. Cwirla, L. L. Lanier, and M. M. Davis. 1989. Polymerase chain reaction with single-sided specificity: analysis of T cell receptor δ chain. Science 24:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enders, B., E. Hundt, and B. Knapp. 1992. Strategies for the development of an antimalarial vaccine. Vaccine 10:920-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glass, E. J., R. A. Oliver, and G. C. Russell. 2000. Duplicated DQ haplotypes increase the complexity of restriction element usage in cattle. J. Immunol. 165:134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goff, W. L., W. C. Johnson, S. M. Parish, G. M. Barrington, W. Tuo, and R. A. Valdez. 2001. The age-related immunity in cattle to Babesia bovis infection involves the rapid induction of interleukin-12, interferon-γ, and inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression in the spleen. Parasite Immunol. 23:463-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Good, M. F. 2001. Towards a blood-stage vaccine for malaria: are we following all the leads? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hines, S. A., G. H. Palmer, W. C. Brown, C. E. Suarez, O. Vidotto, T. F. McElwain, and A. C. Rice-Ficht. 1995. Genetic and antigenic characterization of Babesia bovis merozoite spherical body protein Bb-1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 69:149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hines, S. A., G. H. Palmer, D. P. Jasmer, W. L. Goff, and T. F. McElwain. 1995. Immunization of cattle with recombinant Babesia bovis merozoite surface antigen-1. Infect. Immun. 63:349-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horwitz, J. 1992. Alpha-crystallin can function as a molecular chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10449-10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishiguro, N., A. Tanaka, and M. Shinagawa. 1990. Sequence analysis of bovine T-cell receptor α chain. Immunogenetics 31:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakob, U., M. Gaestel, K. Engel, and J. Buchner. 1993. Small heat-shock proteins are molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 268:1517-1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khusmith, S., Y. Charoenvit, S. Kumar, M. Sedegah, R. L. Beaudoin, and S. L. Hoffman. 1991. Protection against malaria by vaccination with sporozoite surface protein 2 plus CS protein. Science 252:715-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knapp, B, E. Hundt, B. Enders, and H. A. Kupper. 1992. Protection of Aotus monkeys from malaria infection by immunization with recombinant hybrid proteins. Infect. Immun. 60:2397-2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindquist, S., and E. A. Craig. 1998. The heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22:631-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löhr, C. V., K. A. Brayton, V. Shkap, R. T. Molad, A. F. Barbet, W. C. Brown, and G. H. Palmer. 2002. Expression of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 operon-associated proteins during mammalian and arthropod infection. Infect. Immun. 70:6005-6012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahoney, D. F. 1986. Studies on the protection of cattle against Babesia bovis infection, p. 539-541. In W. I. Morrison (ed.), The ruminant immune system in health and disease. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 37.McHeyzer-Williams, M. G., J. D. Altman, and M. M. Davis. 1996. Enumeration and characterization of memory cells in the TH compartment. Immunol. Rev. 150:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohamed, R. M., F. Aosai, M. Chen, H.-S. Mun, K. Norose, U. S. Belal, L.-X. Piao, and A. Yano. 2003. Induction of protective immunity by DNA vaccination with Toxoplasma gondii HSP70, HSP30, and SAG1 genes. Vaccine 21:2852-2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mosqueda, J., T. F. McElwain, and G. H. Palmer. 2002. Babesia bovis surface antigen 2 proteins are expressed on the merozoite and sporozoite surface, and specific antibodies inhibit attachment and invasion of erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 70:6448-6455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosqueda, J., T. F. McElwain, D. Stiller, and G. H. Palmer. 2002. Babesia bovis merozoite surface antigen 1 and rhoptry-associated protein 1 are expressed in sporozoites and specific antibodies inhibit sporozoite attachment to erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 70:1599-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moudgil, K. D., E. E. Sercarz, and I. S. Grewal. 1998. Modulation of the immunogenicity of antigenic determinants by their flanking residues. Immunol. Today 19:217-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mun, H.-S., F. Aosai, and A. Yano. 1999. Role of Toxoplasma gondii Hsp70 and Toxoplasma gondii Hsp30/bag1 in antibody formation and prophylactic immunity in mice experimentally infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol. Immunol. 43:471-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norimine, J., C. E. Suarez, T. F. McElwain, M. Florin-Christensen, and W. C. Brown. 2002. Immunodominant epitopes in Babesia bovis rhoptry-associated protein 1 that elicit memory CD4+ T lymphocyte responses in B. bovis-immune individuals are located in the amino-terminal domain. Infect. Immun. 70:2039-2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norimine, J., J. Mosqueda, C. Suarez, G. H. Palmer, T. F. McElwain, G. Mbassa, and W. C. Brown. 2003. Stimulation of T helper cell gamma interferon and immunoglobulin G responses specific for Babesia bovis rhoptry-associated protein 1 (RAP-1) or a RAP-1 protein lacking the carboxy-terminal repeat region is insufficient to provide protective immunity against virulent B. bovis challenge. Infect. Immun. 71:5021-5032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer, G. H., T. F. McElwain, L. E. Perryman, W. C. Davis, D. R. Reduker, D. P. Jasmer, V. Shkap, E. Pipano, W. L. Goff, and T. C. McGuire. 1991. Strain variation of Babesia bovis merozoite surface-exposed epitopes. Infect. Immun. 59:3340-3342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patarroyo, M. E., P. Romero, M. L. Torres, P. Clavijo, A. Moreno, A. Maritines, R. Rodríguez, F. Buzman, and E. Cabezas. 1987. Induction of protective immunity against experimental infection with malaria using synthetic peptides. Nature 328:629-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rand, K. N., T. Moore, A. Sriskantha, K. Spring, R. Tellam, P. Willadsen, and G. S. Cobon. 1989. Cloning and expression of a protective antigen from the cattle tick Boophilus microplus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:9657-9661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reduker, D. W., D. P. Jasmer, W. L. Goff, L. E. Perryman, W. C. Davis, and T. C. McGuire. 1989. A recombinant surface protein in Babesia bovis elicits bovine antibodies that react with live merozoites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 35:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinherz, E. L., K. Tan, L. Tang, P. Kern, J.-H. Liu, Y. Xiong, R. E. Hussey, A. Smolyar, B. Hare, R. Zhang, A. Joachimiak, H.-C. Chang, G. Wagner, and J.-H. Wang. 1999. The crystal structure of a T cell receptor in complex with peptide and MHC class II. Science 286:1913-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharif, S., B. A. Mallard, B. N. Wilkie, J. M. Sargeant, H. M. Scott, J. C. M. Dekkers, and K. E. Leslie. 1998. Associations of the bovine major histocompatibility complex DRB3 (BoLA-DRB3) alleles with occurrence of disease and milk somatic cell score in Canadian dairy cattle. Anim. Genet. 29:185-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shoda, L. K. M., J. Florin-Christensen, M. Florin-Christensen, G. H. Palmer, and W. C. Brown. 2000. Babesia bovis-stimulated macrophages express interleukin-1β, interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and nitric oxide, and inhibit parasite replication in vitro. Infect. Immun. 68:5139-5145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stich, R. W., L. K. M. Shoda, M. Dreewes, B. Adler, T. W. Jungi, and W. C. Brown. 1998. Stimulation of nitric oxide production in macrophages by Babesia bovis. Infect. Immun. 66:4130-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stich, R. W., A. C. Rice-Ficht, and W. C. Brown. 1999. Babesia bovis: common protein fractions recognized by oligoclonal B. bovis-specific CD4+ T cell lines from genetically diverse cattle. Exp. Parasitol. 91:40-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suarez, C. E., T. F. McElwain, E. B. Stephens, V. S. Misha, and G. H. Palmer. 1991. Sequence conservation among merozoite apical complex proteins of Babesia bovis, Babesia bigemina and other apicomplexa. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 49:329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tanaka, A., N. Ishiguro, and M. Shinagawa. 1990. Sequence and diversity of bovine T-cell receptor β-chain genes. Immunogenetics 32:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tetzlaff, C. L., A. C. Rice-Ficht, V. M. Woods, and W. C. Brown. 1992. Induction of proliferative responses of T cells from Babesia bovis-immune cattle with a recombinant 77-kilodalton merozoite protein (Bb-1). Infect. Immun. 60:644-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tuo, W., G. H. Palmer, T. C. McGuire, D. Zhu, and W. C. Brown. 2000. Interleukin-12 as an adjuvant promotes immunoglobulin G and type 1 cytokine recall responses to major surface protein 2 of the ehrlichial pathogen Anaplasma marginale. Infect. Immun. 68:270-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Eijk, M. J. T., J. A. Stewart-Haynes, and H. A. Lewin. 1992. Extensive polymorphism of the BoLA-DRB3 gene distinguished by PCR-RFLP. Anim. Genet. 23:483-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wright, I. G., R. Casu, M. A. Commins, B. P. Dalrymple, K. R. Gale, B. V. Goodger, P. W. Riddles, D. J. Waltisbuhl, I. Abetz, D. A. Berrie, Y. Bowles, C. Dimmock, T. Hayes, H. Kalnins, G. Leatch, R. McCrae, P. E. Montague, I. T. Nisbet, F. Parrodi, J. M. Peters, P. C. Scheiwe, W. Smith, K. Rode-Bramanis, and M. A. White. 1992. The development of a recombinant Babesia vaccine. Vet. Parasitol. 44:3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright, I. G., B. V. Goodger, and I. A. Clark. 1988. Immunopathophysiology of Babesia bovis and Plasmodium falciparum infections. Parasitol. Today 4:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang, Y., G. H. Palmer, J. R. Abbott, C. J. Howard, J. C. Hope, and W. C. Brown. 2003. CpG ODN 2006 and IL-12 are comparable for priming Th1 lymphocyte and IgG responses in cattle immunized with a rickettsial outer membrane protein in alum. Vaccine 21:3307-3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]