Abstract

This paper characterized bovine extraocular muscles (EOMs) using creep, which represents long-term stretching induced by a constant force. After preliminary optimization of testing conditions, 20 fresh EOM samples were subjected to four different loading rates of 1.67, 3.33, 8.33, and 16.67%/s, after which creep was observed for 1,500 s. A published quasilinear viscoelastic (QLV) relaxation function was transformed to a creep function that was compared with data. Repeatable creep was observed for each loading rate and was similar among all six anatomical EOMs. The mean creep coefficient after 1,500 seconds for a wide range of initial loading rates was at 1.37 ± 0.03 (standard deviation, SD). The creep function derived from the relaxation-based QLV model agreed with observed creep to within 2.7% following 16.67%/s ramp loading. Measured creep agrees closely with a derived QLV model of EOM relaxation, validating a previous QLV model for characterization of EOM biomechanics.

1. Introduction

Since strabismus surgery manipulates extraocular muscles (EOMs) mechanically to correct binocular misalignment, accurate determination of quasistatic biomechanical properties of EOMs may be important. Classical studies investigated the uniaxial force and length relationship for EOMs [1–4]. More recently, comprehensive biomechanical methods have been employed to characterize constitutive models [5] for EOMs, representing their viscoelastic, or history-dependent relationship between stress and strain [6, 7]. Several important mechanical behaviors reflect viscoelasticity: hysteresis, relaxation, attenuation of acoustic waves, and creep.

Hysteresis is history dependent variation in mechanical behavior, resulting in differences in stress between loading and unloading phases. Hysteresis implies work, energy dissipation due to loading and unloading [5, 8, 9]. Relaxation describes how a material deformed by external perturbation returns to equilibrium. In stress relaxation testing, a material is rapidly subjected to displacement and then maintained over an extended time interval at the same displacement by external feedback while a decline in required external force is observed [6, 10–13].

Creep is the tendency of a material to deform permanently under constant force. To characterize creep, tensile loading is rapidly imposed and maintained at a constant level while specimen elongation is observed over an extended time [13, 14]. Creep is likely to be particularly significant in binocular alignment and strabismus, where agonist and antagonist EOMs remain under loading for extended time periods, and where such loading is purposely altered by, for example, strabismus surgery that alters EOM tension.

While viscoelastic properties have often been neglected in interpretation of conventional EOM length-tension data, realistic constitutive modeling is essential for accurate finite element models (FEMs) that graphically simulate interactions of EOMs with orbital connective tissues. Supporting this contention, Quaia et al. [7] and our previous investigation [6] highlighted the need for valid constitutive models of EOMs in application of quasilinear viscoelastic (QLV) theory to constitutive modeling.

Linear elasticity theory is well established for strains of ≤3% in generic materials. Soft tissues generally, however, undergo larger physiological strains in the range of tens of percent where behavior becomes nonlinear. Modeling of EOMs should consider the hyperelastic nature of soft tissue, which means that it is highly nonlinearly elastic [12, 15–20] Fung's QLV theory [5, 21–23] is appropriate because it incorporates both linear viscoelastic and nonlinear elastic characteristics. We previously reported that a QLV model based upon in vitro relaxation data was effective in describing mechanical behavior of passive bovine EOMs [6].

Quaia et al. found limitations in QLV describing constitutive properties of in vivo simian EOMs at short-time scale and proposed a modification that they termed adaptive quasilinear viscoelasticity (AQLV) [7]. Although AQLV was superior to QLV in describing EOM properties relevant to the most rapid eye movements (saccades), the approach is computationally intensive and requires extensive data collection that would limit its practicality for FEM. We supposed that the simpler QLV formulation might be adequate to quasistatic, passive behavior of EOMs relevant in binocular alignment and strabismus.

Since the EOMs are not contracting when under tensile loading, we emulated a previous study with the assumption that absence of perfusion and innervation would not strongly influence constitutive properties [6]. By investigating EOM creep, we aimed to extend understanding of their time-dependent stress-strain behavior and to validate the previously reported relaxation-based QLV model applicable to FEM [6].

2. Methods

The approach was similar to that previously published [6]. The EOM specimens prepared from heads of cattle freshly slaughtered for food. The total time from slaughter to mechanical testing ranged from 3 to 4 hours. During the preparation of specimens, the tissues were constantly irrigated with lactated Ringer solution, which was kept at 37°C, to prevent any dehydration. The EOM specimens were cut into 2∼3 cm long rectangular prisms (length of actual bovine EOMs) having 2 mm × 2 mm cross-section. Actual test length of each specimen was 10 mm, with ≤5 mm on both ends that was clamped on the load cell, excluding the terminal tendon. As in the previous study, a tabletop microtensile load cell, Instron model 4411 (Instron, Norwood, Mass, Series IX software) was enclosed in a plastic chamber where warm water vapor and radiant heat maintained physiologic 97% humidity and 37°C temperature as indicated by a sensor (Fisher Scientific, Chino, Calif). Preconditioning was omitted because a previous investigation of passive EOM relaxation properties demonstrated that preconditioning did not influence results [6]. For both creep testing and preliminary experiments to optimize the testing parameters, total of 60 EOM specimens from 8 different bovine orbits were used.

2.1. Creep Testing

We determined the reduced creep (ε(t)/ε(0)). In ideal creep testing, an initial tensile force should be imposed on the specimen instantaneously and then maintained at a constant level for an extended time [5, 13]. Since instantaneous imposition of tensile force is physically impossible, tensile force is rapidly increased at a constant ramp rate to a level that is subsequently maintained. Based upon tensile-loading results [6], we selected 0.2 N, which produces 30% strain that is well within the linear range, as an appropriate ramp force. Although the maximum loading rate of the load cell was 550 mm/min, it was necessary to limit the rate to 100 mm/min to maintain stable force feedback. Therefore, all the creep tests were performed at the following four rates: 10, 20, 50, and 100 mm/min, equivalent to 1.67, 3.33, 8.33, and 16.67%/s, respectively. After the initial loading of 0.2 N was imposed, this force was then maintained by the load cell's feedback servo for 1,500 s during recording of specimen length.

2.2. Fung's Quasilinear Viscoelasticity Theory

It represents stress as a function of strain and time. In stress relaxation testing, strain is held constant and the stress declines as a function of time alone:

| (1) |

where G(t) is the time dependent reduced relaxation function with G(0) = 1, and σ0 is initial stress. Similarly, for static creep in which stress is held constant, strain varies as a function of time alone:

| (2) |

where J(t) is the time dependent reduced creep function with J(0) = 1 and ε0 is the initial strain. For linear viscoelasticity [5], which is a special case of the more general QLV theory [24], time-varying stress relaxation function G(t) and creep function J(t) should be related as follows:

| (3) |

or

| (4) |

where G(s) and J(s) are Laplace transforms of the functions G(t) and J(t), respectively. A nonlinear least square method was used in previous study fit the stress relaxation data, determining constants a, b, c, d, g, and h [6]:

| (5) |

Using the Laplace transform of the stress relaxation function and (4), a predicted creep function for EOM was determined using MatLab (The Mathworks Inc, Natick, Mass, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

As is typical for creep testing generally [5, 24, 25], a logarithmically increasing displacement was observed after initial ramp loading of each specimen, without asymptote. Data were plotted as normalized displacement J(t), the ratio of instantaneous specimen length to initial length.

3.1. Creep for Each Anatomical EOM

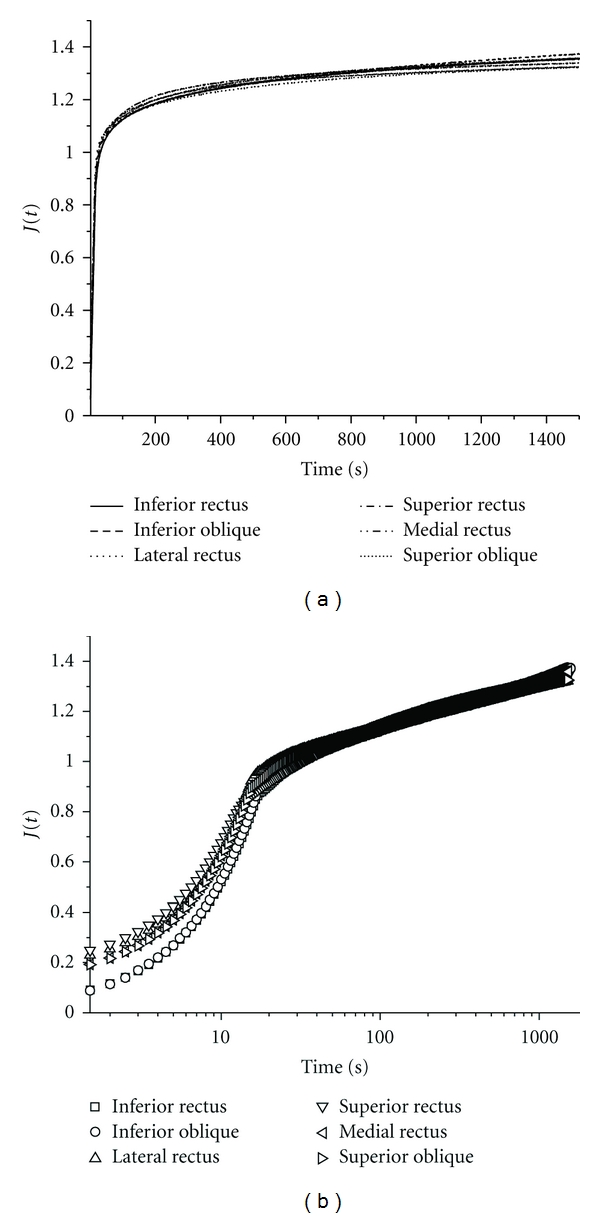

Although relaxation and tensile properties were similar among the four rectus and both oblique bovine EOMs in the previous study [6], preliminary experiments were conducted on two specimens of each of the six EOMs to determine if they exhibit similar creep at 3.33%/s strain rate. As can be seen from Figure 1, creep was essentially identical for all six EOMs.

Figure 1.

Mean normalized displacement J(t) plotted for two specimens each of the six bovine EOMs in both linear and semi-log scales. All EOMs exhibited similar creep to 1.34 ± 0.02 (SD) maximum.

3.2. Dependence of Creep on Ramp-Loading Rate

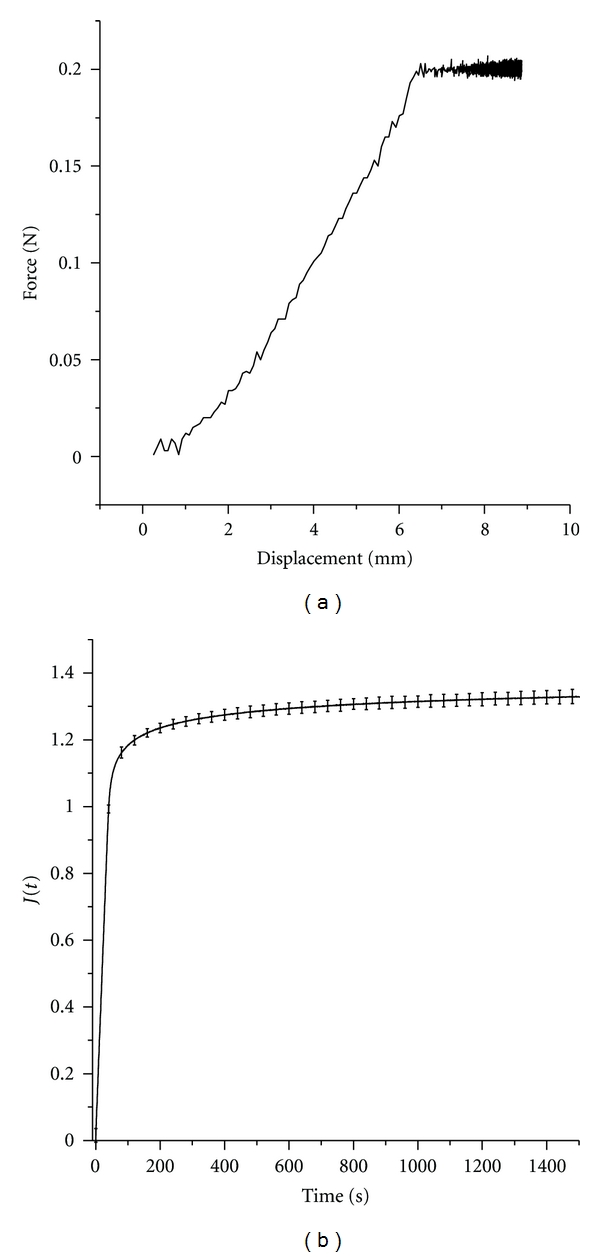

In order to determine if EOM properties depend on initial loading, experiments were conducted for five specimens each at four ramp-loading rates: 1.67, 3.33, 8.33, and 16.67%/s. As an example, Figures 2(a) and 2(b) show the force displacement and creep plots for 0.2 N force. Since all EOMs exhibited similar creep, differentiation of each anatomical EOM was unnecessary.

Figure 2.

Mean creep for 1.67%/s loading rate for 5 EOM specimens. (a) Force versus displacement. After initial ramp loading achieved at around 6 mm deformation, the force was held constant at 0.2 N. (b) Reduced creep coefficients over 1,500 seconds. Maximum creep coefficient SD was 0.023.

Creep at other ramp-loading rates was similar to Figure 2, with maximum standard deviations (SDs) for five specimens each of 0.029, 0.056, and 0.036 for 3.33, 8.33, and 16.67%/s loading, respectively.

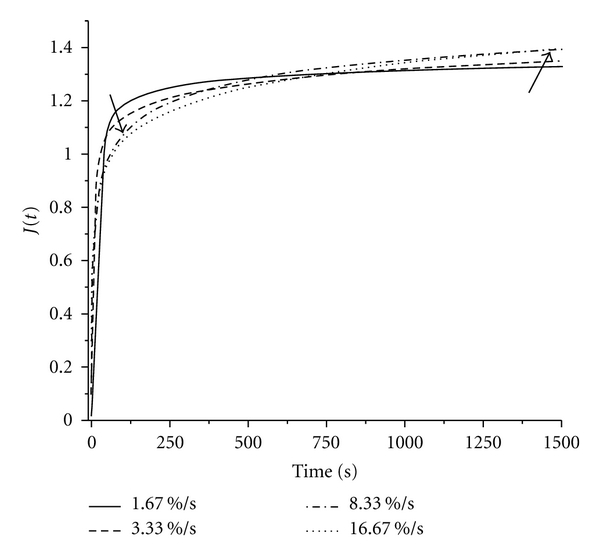

As seen in Figure 3, for all four initial loading rates, creep coefficients at the end of 1,500 seconds were similar at 1.37 ± 0.033. Despite the ultimate similarity of creep behavior, the linear part of each curve under initial loading steepened as loading rate increased, and the shape of each curve varied with loading rate (Figure 3). As loading rate decreased, the curve showed slower elongation. Since EOM is a soft tissue, reaching a true asymptotic value during creep testing is neither practical nor theoretically necessary [5, 25]. Although the creeping behavior exhibited by EOM after ramp loading is used in its viscoelastic characterization, the rate-dependent ramp behavior can also be used to understand the contribution of EOM elasticity in its overall creep behavior. With behavior of the EOM during the ramp phase being less affected by viscosity as the loading rate is decreased, one can optimize the loading rate for tensile testing to extract the tensile elasticity of the EOM.

Figure 3.

Comparison of creep at 4 different initial loading rates. The left arrow indicates that a lower reduced creep coefficient is reached at the end of initial ramp loading as the ramp-loading rate increases. The right arrow indicates that a higher creep coefficient is reached after 1500 seconds as ramp-loading rate increases.

3.3. Conversion of Relaxation Function to Creep Function

All constants in the reduced relaxation function were derived from the published relaxation function [6] and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

QLV relaxation model parameters.

| a | 2.81 |

| b (1/sec) | 1.57 |

| c | 0.86 |

| d (1/sec) | 1.4 × 10−4 |

| g | 0.34 |

| h (1/sec) | 1.7 × 10−2 |

Using parameters extracted from the QLV relaxation model, (4) in the time domain was converted to a reduced creep function using the inverse Laplace transform function and symbolic toolbox in Matlab, 6 constant values from the Laplace S domain (6), and 7 constants from the time domain (7) of the resulting reduced creep function are listed in Table 2

Table 2.

| a1 | 2.81 | C1 | 1.6137 × 10−4 |

| a2 | 1.57 | C2 | 4.0473 × 1021 |

| a3 | 0.86 | C3 | 0.2312 |

| a4 | 1.4 × 10−4 | C4 | 1.5097 × 1022 |

| a5 | 0.34 | C5 | 1.6788 × 1022 |

| a6 | 1.7 × 10−2 | C6 | 0.2434 |

| C7 | 1.1487 |

| (6) |

| (7) |

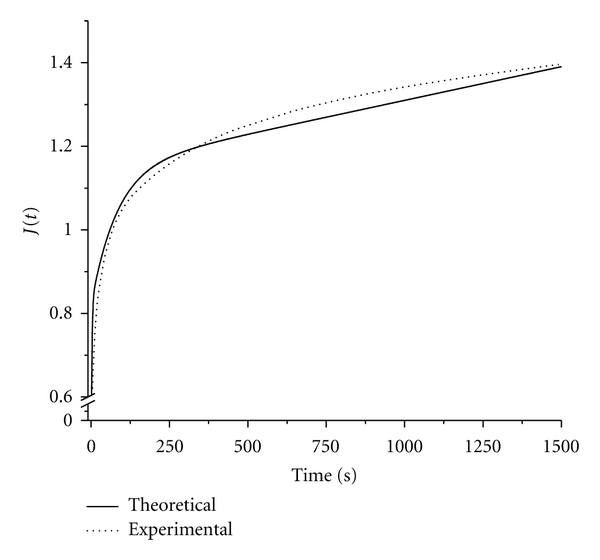

Since ideal initial loading is assumed instantaneous, data obtained at higher rates of initial ramp loading should more closely reflect ideal creep. Hence, the reduced creep function derived from the reduced relaxation function was compared with experimental data for the highest ramp-loading rate, showing close agreement (Figure 4). Experimental creep coefficient values fell within ±2.7% of theoretical values for all time points tested.

Figure 4.

Observed reduced EOM creep function, and theoretical function derived from the reduced relaxation function.

When an EOM is innervated and perfused with oxygenated blood, it is constantly under tension. It is important to understand EOM creep properties for simulation of the common situation where a physiologically relaxing EOM is still experiencing tensile force exerted by its antagonist. In the current study, passive bovine EOM creep was investigated within the framework of linear viscoelasticity by comparing converted creep function from QLV model based upon stress relaxation data [6]. The current experiment varied initial elongation rate and demonstrated excellent agreement with the theoretical prediction based upon QLV relaxation model. It has been suggested that initial ramp loading for creep testing of articular cartilage should occur within 250 ms [20]; however, even over a longer time of 800 ms, the data for bovine EOMs agreed closely with values derived from relaxation function.

Regardless of which anatomical rectus or oblique EOM was tested, creep for initial ramp-loading rates from 1.67 to 16.7%/s showed similar asymptotic creep coefficients of 1.37 ± 0.03 over 1,500 s. However, dynamic creep varied with initial strain rate. Creep coefficient J(t) reached a higher initial value when the loading rate was lower, but subsequently increased more slowly (Figure 3). It seems reasonable to assume that each EOM specimen has the same elasticity. It is a well-accepted notion that when solid specimen is stretched slowly, dynamic contributions are reduced because at low initial loading speed, elasticity predominates over viscous effects [26–28]. With predominantly elastic effects, less energy is dissipated than when initial loading is rapid. Since the present models were based upon data from low strain rates, we suggest that the QLV models derived from these investigations are most applicable to slow eye movements such as fixations and pursuit. Since loading for both relaxation and creep tests closely approximates ideal step loading, the relaxation and creep functions are likely to accurately reflect EOM viscosity.

4. Conclusion

This paper validated a previously reported QLV model for EOM relaxation. Since a reduced creep function is the inverse Laplace transform of a reduced relaxation function, agreement between experimental creep and the previously published reduced relaxation function constitutes a strong test of the relaxation-based QLV model for passive EOMs, with experimental agreement to within ±2.7% of theoretical values. Hence, we can infer that a QLV model based upon relaxation effectively describes the constitutive properties of passive EOMs. The present validation of the quantitative viscoelastic constitutive relationship for passive bovine EOM provides better understanding of EOM biomechanics, in a theoretical framework practical for graphical simulation of quasistatic ocular motility using FEM.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by US Public Health Service, National Eye Institute: Grants EY08313 and EY00331; Research to Prevent Blindness. J. Demer is Leonard Apt Professor of Ophthalmology.

References

- 1.Robinson DA, O’Meara DM, Scott AB, Collins CC. Mechanical components of human eye movements. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1969;26(5):548–553. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.26.5.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins CC, Carlson MR, Scott AB, Jampolsky A. Extraocular muscle forces in normal human subjects. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 1981;20(5):652–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simonsz HJ. Force-length recording of eye muscles during local anesthesia surgery in 32 strabismus patients. Strabismus. 1994;2(4):197–218. doi: 10.3109/09273979409035475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quaia C, Ying HS, Nichols AM, Optican LM. The viscoelastic properties of passive eye muscle in primates. I: static and step responses. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004850. Article ID e4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fung YC. Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoo LH, Kim H, Gupta V, Demer JL. Quasi-linear viscoelastic behavior of bovine extra-ocular muscle tissue. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2009;50(8):3721–3728. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quaia C, Ying HS, Optican LM. The viscoelastic properties of passive eye muscle in primates. II: testing the quasi-linear theory. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006480. Article ID e6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shall MS, Dimitrova DM, Goldberg SJ. Extraocular motor unit and whole-muscle contractile properties in the squirrel monkey: summation of forces and fiber morphology. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;151(3):338–345. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sklavos S, Dimitrova DM, Goldberg SJ, Porrill J, Dean P. Long time-constant behavior of the oculomotor plant in barbiturate- anesthetized primate. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95(2):774–782. doi: 10.1152/jn.00584.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downs JC, Suh JKF, Thomas KA, Bellezza AJ, Hart RT, Burgoyne CF. Viscoelastic material properties of the peripapillary sclera in normal and early-glaucoma monkey eyes. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2005;46(2):540–546. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin HC, Kwan MKW, Woo SLY. On the stress relaxation properties of the anterior cruciate ligament(ACL). In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers; 1987; Advances in Bioengineering; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller CE, Wong CL. Trabeculated embryonic myocardium shows rapid stress relaxation and non-quasi-linear viscoelastic behavior. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33(5):615–622. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: theory and experiments. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1980;102(1):73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nash IS, Greene PR, Foster CS. Comparison of mechanical properties of keratoconus and normal corneas. Experimental Eye Research. 1982;35(5):413–424. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(82)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto JG, Fung YC. Mechanical properties of the heart muscle in the passive state. Journal of Biomechanics. 1973;6(6):597–616. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(73)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huyghe JM, van Campen DH, Arts T, Heethaar RM. The constitutive behaviour of passive heart muscle tissue: a quasi-linear viscoelastic formulation. Journal of Biomechanics. 1991;24(9):841–849. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90309-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers BS, McElhaney JH, Doherty BJ. The viscoelastic responses of the human cervical spine in torsion: experimental limitations of quasi-linear theory, and a method for reducing these effects. Journal of Biomechanics. 1991;24(9):811–817. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toms SR, Dakin GJ, Lemons JE, Eberhardt AW. Quasi-linear viscoelastic behavior of the human periodontal ligament. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35(10):1411–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller CE, Vanni MA, Keller BB. Characterization of passive embryonic myocardium by quasi-linear viscoelasticity theory. Journal of Biomechanics. 1997;30(9):985–988. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woo SL-Y, Simon BR, Kuei SC, Akeson WH. Quasi-linear viscoelastic properties of normal articular cartilage. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1980;102(2):85–90. doi: 10.1115/1.3138220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fung YC. Elasticity of soft tissues in simple elongation. The American Journal of Physiology. 1967;213(6):1532–1544. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1967.213.6.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung YC. Stress-Strain-History Relations of Soft Tissues in Simple Elongation, Biomechanics: Its Foundations and Objectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simin N, Bilston LE, Phan-Thien N. Viscoelastic properties of pig kidney in shear, experimental results and modelling. Rheologica Acta. 2002;41(1):180–192. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornton GM, Frank CB, Shrive NG. Ligament creep behavior can be predicted from stress relaxation by incorporating fiber recruitment. Journal of Rheology. 2001;45(2):493–507. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon BR, Coats RS, Woo SLY. Relaxation and creep quasilinear viscoelastic models for normal articular cartilage. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 1984;106(2):159–164. doi: 10.1115/1.3138474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu X, Daehn GS. Effect of velocity on flow localization in tension. Acta Materialia. 1996;44(3):1021–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ze-Ping W. Void-containing nonlinear materials subject to high-rate loading. Journal of Applied Physics. 1997;81(11):7213–7227. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholas T. Tensile testing of materials at high rates of strain. Experimental Mechanics. 1981;21(5):177–185. [Google Scholar]