Abstract

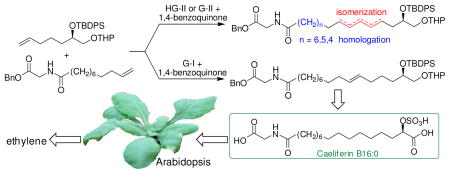

A cross metathesis- (CM-) based synthesis of the caeliferins, a family of sulfooxy fatty acids that elicit plant immune responses is reported. Unexpectedly, detailed NMR-spectroscopic and mass spectrometric analyses of CM reaction mixtures revealed extensive isomerization and homologation of starting materials and products. It is shown that the degree of isomerization and homologation in CM strongly correlates with substrate chain length and lipophilicity. Side-product suppression requires appropriate catalyst selection and use of 1,4-benzoquinone as hydride scavenger.

The caeliferins (1-4) are a family of insect-derived small molecule signals that play an important role in plant defenses. Originally isolated from grasshopper saliva, these molecules elicit immune responses in corn and Arabidopsis that attract natural predators of the feeding herbivores.1

Despite their interesting role in insect-plant interactions, a lack of synthetic caeliferin samples has prevented further study of their mode of action, including the identification of specific receptors in plants that activate immune responses. We envisioned that a cross metathesis (CM)-based approach would provide us with the flexibility to create all known caeliferins 1-4 from chiral synthon 9 via variation of its long-chained metathesis partners, 7 and 8 (Scheme 1). Using a large excess of inexpensive 7 or 8 in the metathesis reaction should allow suppression of competing dimerization of 9.

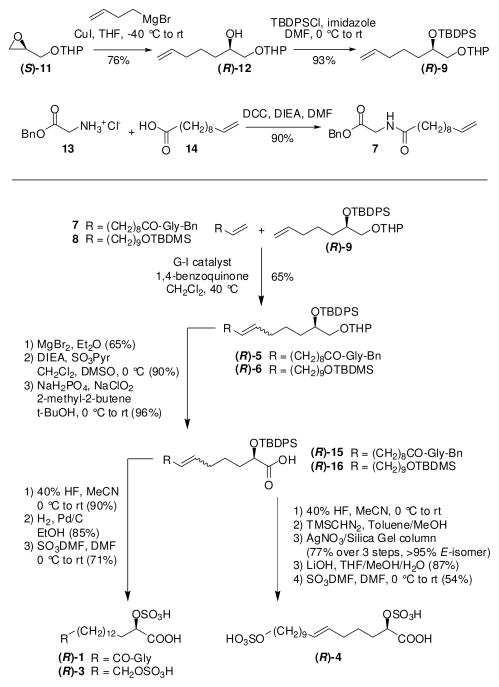

Scheme 1.

Caeliferin Structures and Retrosynthesis

The enantiomers of 9 were obtained from THP-protected glycidol via a Cu(I) catalyzed Grignard reaction with 4-bromo-1-butene (Scheme 2).2 Alkenes 7 and 8 were each prepared in one step from commercially available precursors.3

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Caeliferins 1, 3, and 4

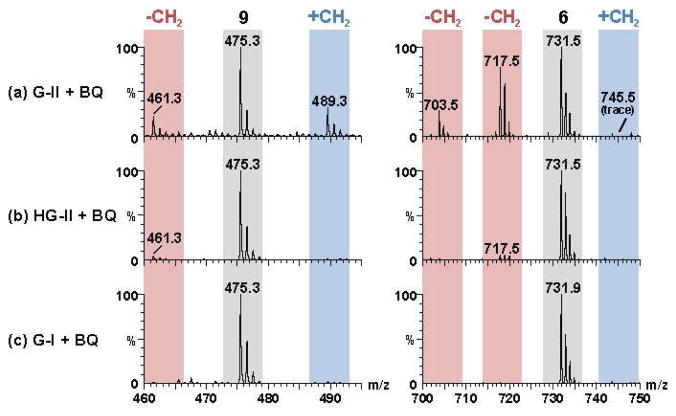

Next we investigated conditions for CM of 9 with 7 or 8.4 Strikingly, CM on substrates 9 and 8 using Grubbs 1st generation (G-I), Grubbs 2nd generation (G-II), or Hoveyda-Grubbs 2nd generation (HG-II) catalysts resulted in complex product mixtures, containing only 20–50% of desired 6 in addition to significant quantities of side products. ESI+-MS analysis of CM reactions revealed CH2-insertions and deletions for substrate 9 as well as CH2-deletions for product 6 (Figures 1, S3). Similar results were obtained in CM of 9 with 7 (Figure S4). Using the more active G-II or HG-II catalysts, significant amounts of chain shortened starting materials and products were already observed after 2 h, at which time less than 40% of starting material 9 had been consumed. Previous studies have shown that isomerization as well as CH2-insertion and deletion during metathesis reactions are likely the result of ruthenium hydride formation,5,6 which can be suppressed by addition of hydride scavengers, e.g. 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ).7 We found that even with the addition of BQ, the use of either G-II or HG-II resulted in formation of significant quantities of side products (Figures S3, S4).

Figure 1.

ESI+-MS analysis of CM reaction mixtures showing [M+Na+] for starting material 9 and product 6. Ion signals corresponding to chain shortened and chain extended homologues are shown in red and blue, respectively. Conditions: (a) G-II (0.05 equiv), BQ (0.1 equiv), 40 °C, 20 h; (b) HG-II (0.05 equiv), BQ (0.1 equiv), 40 °C, 20 h; (c) G-I (0.05 equiv), BQ (0.1 equiv), 40 °C, 20 h.

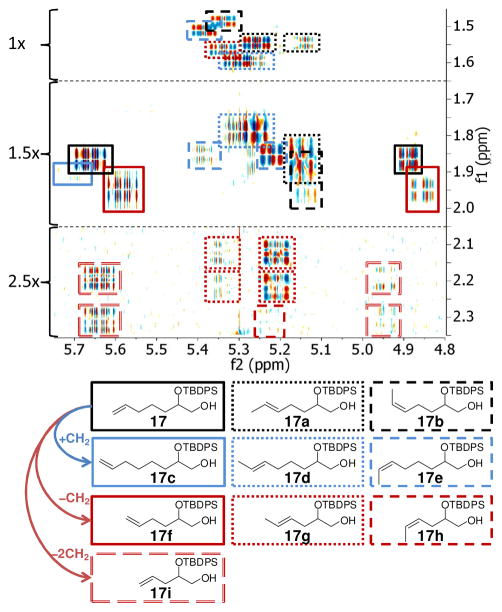

Our ESI+-MS-based analyses revealed significant homologation; however, the extent of CM-induced product and starting material isomerization remained unclear. Building on recent experience using 2D NMR spectroscopy for the analysis of mixtures,8 we used high-resolution dqfCOSY spectra to further characterize CM reaction outcomes. To simplify NMR-spectroscopic analysis, we isolated the mixture of residual 9, its isomers and homologues from G-II-catalyzed CM of 8 and 9 and subsequently removed the stereogenic THP group, producing a corresponding mixture of 17 and derivatives (Figure 2). dqfCOSY spectra8 of this mixture enabled identification of all significant isomerization and homologation products (17a–i), revealing extensive double-bond isomerization and confirming CH2-deletions in 9 during CM, which explains the formation of norhomologues of metathesis product 6. Analysis of the dqfCOSY spectra further revealed large quantities of the chain-extended compounds 17d and 17e. However, only trace amounts of the chain-extended terminal alkene 17c were found. This is consistent with the hypothesis that CH2-extended variants of 9 form mostly via ethylidene-transfer during CM of isomerized starting materials, without significant contribution from isomerized product 6 (isomerization and homologation pathways are shown in Figure S2). The low abundance of the CH2-extended terminal alkene 17c also explains that only trace amounts of CH2-insertion products of 6 were observed (m/z 745.5 in Figure 1), as their formation in the absence of chain-extended terminal alkenes would require multiple isomerization and metathesis steps (see Figure S2). In contrast to G-II and HG-II, use of G-I catalyst in the presence of BQ did not result in homologation (Figure 1c) or isomerization (as confirmed by dqfCOSY), even when using as much as 0.1 equivalents of catalyst and reaction times of up to 48 h. Using G-I catalyst, 6 was obtained in 80% yield (E/Z = 4:1), based on consumed 9.

Figure 2.

Section of dqfCOSY spectrum of the mixture of 17 and its isomers and homologues, as derived from the corresponding mixture of isomers and homologues of 9 isolated from CM of 8 with 9 using G-II and BQ (600 MHz, CDCl3, see Figure S1 for full spectrum). Intensity of parts of the spectrum was scaled (1.5x, 2.5x).

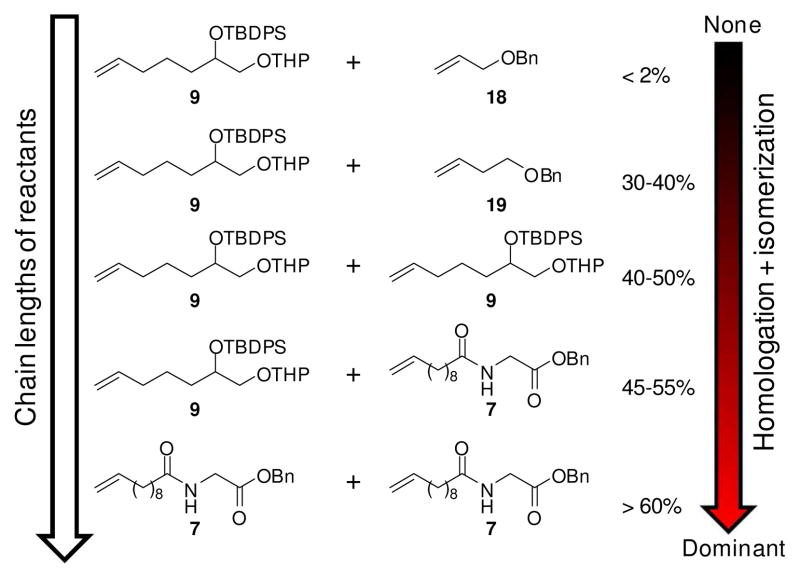

Given that both G-II and HG-II have been employed successfully in many CM reactions,9 we investigated whether the degree of homologation and isomerization depends on specific properties of the reactants 7-9 (Figure 3). Using G-II catalyst without BQ, we found that CM of 9 with allyl benzyl ether proceeded cleanly without formation of isomerized products or substrates, whereas CM of 9 and homoallyl benzyl ether and homodimerization of 9 consistently yielded significant amounts of isomerized and homologated products (Figure S6). Even larger quantities of isomerized and homologized products were obtained in G-II-catalyzed homodimerization reactions of 7 and 8 (Figures S7, S8), similar to amounts of side products produced in G-IIcatalyzed CM reactions of 9 with 7 or 8 (Figures S3, S4). Thus it appears that the severity of isomerization in our metathesis reactions generally correlates with the chain-lengths of the reaction partners and products (Figures 3, S3, S4, S6–S8). That long-chain, lipophilic substrates are particularly susceptible to homologation and isomerization during CM is also suggested by recent acyclic diene metathesis (ADMET) studies.6,10 Avoiding homologation and isomerization is of importance for both ADMET and natural product synthesis, as physical or biological properties may be affected greatly by small amounts of structurally similar impurities. Our results show that among tested catalysts, G-I with added BQ is most suitable for CM involving long-chain substrates.

Figure 3.

Amounts of detected homologation and isomerization products correlate with chain lengths of CM reactants. Percentages refer to amounts of homologated products formed in G-II-catalyzed CM without BQ, as determined by ESI+-MS (see Supporting Information for conditions). Additional side product formation occurs due to product isomerization.

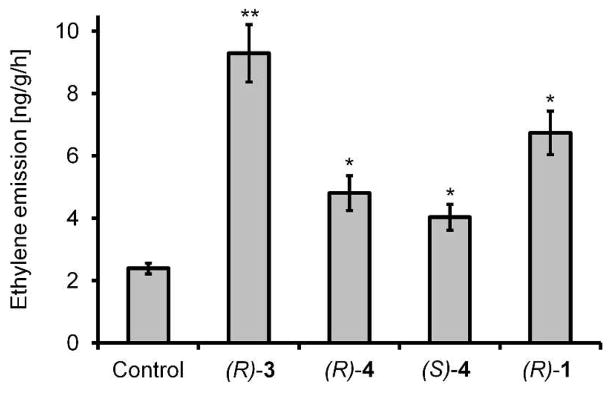

To complete synthesis of the caeliferins, CM products 5 and 6 were deprotected11 and converted into acids 15 and 16 via sequential Swern and Pinnick oxidation.12 Desilylation followed by hydrogenation and sulfation produced 1 and 3. For the preparation of pure (E)-4, desilylated 16 was methylated and freed from contaminating (Z)-isomer using AgNO3-impregnated silica gel.13 Samples of synthetic caeliferins were tested in Arabidopsis1 for their activity to elicit immune responses and thus mimic the effects of a feeding herbivore’s saliva. When delivered at concentrations corresponding to those found in grasshopper saliva,1 the tested caeliferins strongly induced ethylene production (Figure 4), revealing differences in the relative potency of different compounds.1 Ethylene-inducing activity of synthetic caeliferin A16:0 (3) is similar to that previously reported.1

Figure 4.

Ethylene emission of Arabidopsis seedlings after treatment with synthetic caeliferin solutions; errors bars, s.d.; two-tailed Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.005.

In summary, we report the first enantioselective syntheses of (R)-1, (R)-3, (R)-4 and (S)-4, using CM conditions suitable for long-chained substrates. Our CM-based caeliferin synthesis is flexible and provides access to related compounds, which will enable studies aimed at identifying molecular targets of these elicitors of plant immune responses. Better understanding of the caeliferins’ biological mode of action may facilitate development of sustainable pesticides that take advantage of natural plant defense responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM079571 to F.C.S.), and the O’Reilly Foundation (to I.O.D.). We thank Prof. Geoffrey Coates for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Supporting Figures, experimental procedures, and spectroscopic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Alborn HT, Hansen TV, Jones TH, Bennett DC, Tumlinson JH, Schmelz EA, Teal PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12976–12981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705947104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schmelz EA, Engelberth J, Alborn HT, Tumlinson JH, 3rd, Teal PE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:653–657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811861106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Cahiez G, Chaboche C, Jezequel M. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:2733–2737. [Google Scholar]; (b) Díez E, Dixon DJ, Ley SV, Polara A, Rodríguez F. Helv Chim Acta. 2003;86:3717–3729. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu P, Lin W, Zou X. Synthesis. 2002;8:1017–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Grubbs RH, Burk PL, Carr DD. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:3265–3267. [Google Scholar]; (b) Connon SJ, Blechert S. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:1900–1923. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chatterjee AK, Choi TL, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11360–11370. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hoveyda AH, Zhugralin AR. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Schmidt B. Eur J Org Chem. 2004;9:1865–1880. [Google Scholar]; (b) Courchay FC, Sworen JC, Ghiviriga I, Abboud KA, Wagener KB. Organometallics. 2006;25:6074–6086. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Fokou PA, Meier MAR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1664–1665. doi: 10.1021/ja808679w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mutlu H, de Espinoza LM, Meier MAR. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1404–1445. doi: 10.1039/b924852h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong SH, Sanders DP, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17160–17161. doi: 10.1021/ja052939w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Taggi AE, Meinwald J, Schroeder FC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10364–10369. doi: 10.1021/ja047416n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pungaliya C, Srinivasan J, Fox BW, Malik RU, Ludewig AH, Sternberg PW, Schroeder FC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7708–7713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811918106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Canova S, Bellosta V, Cossy J. Synlett. 2004;10:1811–1813. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rai AN, Basu A. Org Lett. 2004;6:2861–2863. doi: 10.1021/ol049183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sheddan NA, Mulzer J. Org Lett. 2006;8:3101–3104. doi: 10.1021/ol061141u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin H, Chakulski BJ, Rousseau IA, Chen J, Xie XQ, Mather PT, Constable GS, Coughlin EB. Macromolecules. 2004;37:5239–5249. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S, Park JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:439–440. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AB, III, Adams CM, Barbosa SA, Degnan AP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12042–12047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402084101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams CM, Mander LN. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:425–447. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.