Abstract

By linking ecological theory with freely-available Google Earth satellite imagery, landscape-scale footprints of behavioural interactions between predators and prey can be observed remotely. A Google Earth image survey of the lagoon habitat at Heron Island within Australia's Great Barrier Reef revealed distinct halo patterns within algal beds surrounding patch reefs. Ground truth surveys confirmed that, as predicted, algal canopy height increases with distance from reef edges. A grazing assay subsequently demonstrated that herbivore grazing was responsible for this pattern. In conjunction with recent behavioural ecology studies, these findings demonstrate that herbivores' collective antipredator behavioural patterns can shape vegetation distributions on a scale clearly visible from space. By using sequential Google Earth images of specific locations over time, this technique could potentially allow rapid, inexpensive remote monitoring of cascading, indirect effects of predator removals (e.g., fishing; hunting) and/or recovery and reintroductions (e.g., marine or terrestrial reserves) nearly anywhere on earth.

Freely-available satellite imagery of the entire Earth's surface via Google Earth allows examination of landscape features in even the most remote areas, including difficult-to-access habitats within them. Application of this tool has largely focused on terrestrial habitats, with enlightening results ranging from exposing looting of historical sites to secret prison camp buildups 1. Here we demonstrate that by linking ecological theory with this emergent technology, it is possible to remotely observe the landscape-scale footprint of behavioural interactions between predators and prey on shallow coral reefs.

Behavioural cascades, or behaviourally-mediated indirect interactions, have been documented in a variety of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems 2,3. Their landscape-level effects are clearly seen in studies of wolf-elk-aspen interactions 4. Contrary to density-mediated trophic cascade expectations, behavioural cascades can change distributions, rather than solely abundances, of vegetation. Grazing halos—rings of bare substrate devoid of seaweed—have long been noted surrounding coral patch reefs 5,6. Halos have been attributed to fish5 and/or urchin6 herbivory, suggesting that they shelter from predators within reefs and take foraging excursions that radiate outwards from this central refugia. Analogous zones have been documented in other marine systems, such as rocky intertidal benches.

The aim of this study was to determine if the landscape-scale footprint of the collective grazing patterns of small herbivores shown in previous studies – i.e., individuals preferentially foraging in the immediate vicinity of coral reef refugia when faced with predation risk – could be observed remotely using freely-available satellite imagery.

Results

Remote surveys and ground truthing

Heron Island, within Australia's southern Great Barrier Reef (GBR), is located within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Approximately half of the island's reef area is within a no-take marine reserve, while the other half is encompassed within a Conservation Park Zone in which some limited forms of extraction are allowed (e.g., spearfishing on snorkel only; fishing with individual hook and line). In addition, the island and its reefs are accessible only by boat or helicopter, limiting the number of visitors, and therefore the total fishing pressure, to the reefs. As a result, the island's reef system has experienced only limited fishing pressure in recent years.

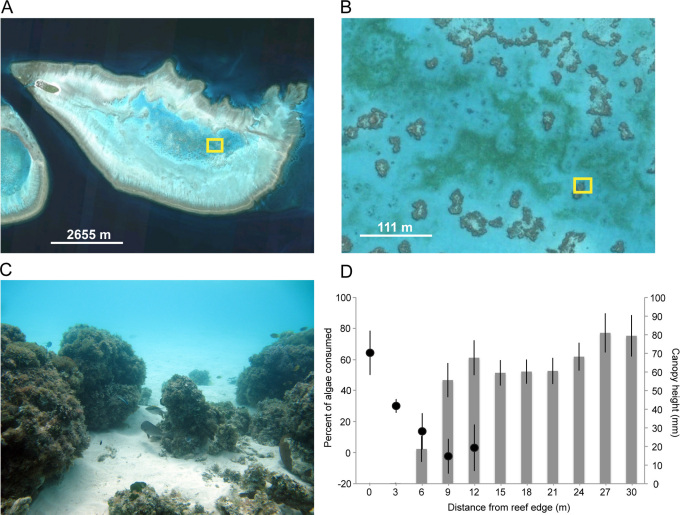

A satellite image survey of the lagoon habitat at Heron Island revealed distinct halo patterns surrounding isolated patch reefs. These reefs were then surveyed in-situ to determine the nature and cause of the halos, showing that halos observed from satellite images (Fig. 1, A–B) were formed almost exclusively within beds of the filamentous, benthically-attached algae Hincksia sp. Within these beds, the images' visible white bands consist of sand devoid of conspicuous algae or other organisms. As predicted from the images, algal canopy height (a proxy for biomass) increases precipitously between 6 – 9 m from reef edges (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. (A – C) Examples of halos (A, B) and reef within halos (C) found at Heron Island, GBR, Australia.

Yellow boxes in (A) and (B) indicate approximate scale of subsequent photos. Images (A) and (B) from Google Earth. (D) Black circles, left-hand axis: percent of algae consumed during grazing assay. Positive values indicate net reduction in algal biomass; negative values can be interpreted as net increase of algal biomass due to algal growth. Grey bars, right-hand axis: standing biomass of algal assemblage surrounding reef, primarily Hincksia sp. Circles and bars are means ± s.e.m.

Grazing assay

To determine the mechanism responsible for halo formation/maintenance, we then conducted a grazing assay to quantify relative levels of herbivory at increasing distances from the reef. This grazing assay demonstrated that herbivore grazing is concentrated primarily within the 9m radius immediately surrounding patch reefs (Fig. 1D). The assay did not aim to determine the species responsible for these patterns, but was used as a spatially-explicit means to assess total grazing pressure at various points over the reef benthos.

Discussion

Two recent studies showed that herbivorous coral reef fishes' grazing behavioural responses to predation risk can dramatically shape the distribution of benthic macroalgae over small scales 7 by restricting prey foraging 8 to areas adjacent to shelter from predators. Grazing halos, an apparent outcome of such behavioural responses, would not be expected following large-scale predator removal by fishing (Fig. 2) because predation risk for herbivorous fishes, urchins, and other grazers would be low, allowing them to forage away from shelter with relative impunity. Results from our grazing assay at Heron Island provide a mechanistic link between the observed pattern of algal biomass distribution and spatial patterns of herbivore grazing surrounding the refugia of patch reefs.

Figure 2. No evidence of halos surrounding patch reefs can be seen on the heavily fished reef adjacent to Panggang Island in Indonesia's Thousand Islands (Kepulauan Seribu) off the coast of Jakarta.

Using time series of Google Earth images in heavily fished areas such as this could allow examination of changes in past and/or future grazing patterns as a function of predator loss - or recovery - over time.

Other possible hypotheses for the mechanism(s) generating and/or maintaining these halos include differences in sediment grain size, small-scale hydrodynamic processes, shading, and/or differences in nutrient availability surrounding patch reefs. In accordance with Randall's 5 test of the first, we visually observed no apparent differences in sand grain size radiating outwards from halo-ringed reefs. In the case of small-scale hydrodynamics, the expectation would be asymmetrical radii of halos in accordance with the dominant direction of flow and/or the pattern of turbulence. This pattern was not observed (Fig. 1 A, B). Additionally, the extremely sheltered nature of the study lagoon means that these reefs receive very little current or wave action. If shading of Hincksia beds by patch reefs were responsible for halo formation, the expectation would be consistent oblong, east-west halo axes in accordance with the sun's arc. Conversely, observed individual halos are either symmetrical or asymmetrical with no clear axis (Fig. 1B). Lastly, higher nutrient availability would be expected immediately surrounding reefs due to the defecation by lagoonal fish and invertebrate fauna that should be disproportionately concentrated around the patch reefs. This pattern runs counter that which would be necessary to drive the observed pattern or macroalgal distribution.

Together, these findings demonstrate that the collective antipredator behavioural patterns of small herbivores are sufficient to shape the distribution of vegetation on a scale clearly visible from space. Analogous vegetation changes in different spatial configurations observed on land using aerial photography are hypothesized to result from similar behavioural responses of prey 9. By using sequential Google Earth images of specific locations and/or imagery from inside versus outside of protected areas, remotely monitoring predator-prey interactions through the patterns they generate over the landscape could serve as a rapid, inexpensive preliminary indicator of the efficacy of marine and terrestrial reserves designed to restore depleted predator populations. Behavioural responses by prey to predators are likely to be apparent far more rapidly than numerical responses because behavioural responses can occur simultaneously over entire populations. Conversely, numerical responses can only occur as fast as predators can consume prey.

It is worth noting that over a spatial or temporal continuum of predation risk for herbivorous fishes and invertebrates, the degree of landscape heterogeneity will likely reflect this continuum. For example, both behavioural and numerical effects of predator loss on herbivores will likely result in more intense grazing farther from shelter as predators, and hence predation risk, declines. The contrast in primary producer biomass between grazed versus ungrazed (or more heavily versus more lightly grazed) reef areas should concomitantly decrease as herbivores' needs for predation refugia are diminished and/or their abundances increase. We may therefore expect to see some evidence of grazing halos when and where predator loss has been moderate – and in particular larger, less distinct halos – resulting in reef landscapes that exhibit a continuum of primary producer heterogeneity or patchiness in accordance with the degree of predator loss experienced. Additionally, in areas where the dominant herbivores are urchins or site-attached fishes (both of which are central place foragers, i.e., are restricted to venturing outwards from a central place to graze regardless of predation risk), we may expect to see evidence of grazing halos even where predation risk is nil. These points both suggest that the approach we propose will be most effective when applied to comparisons of reef landscape heterogeneity (i.e., halo presence, size and contrast with surrounding areas) over space and/or time rather than when used in spatial or temporal isolation (e.g., a ‘snapshot' approach).

This application is generally relevant to ecosystems in which predators affect large-scale vegetation distribution through risk effects on their prey (e.g., Rocky Mountains of North America 4; seagrass beds of Florida; South Africa's savanna). The technique could allow remote monitoring of cascading, indirect effects of predator removals (e.g., due to fishing; hunting) and/or reintroductions (e.g., North America's wolves 4; India's cheetahs; African game reserves) anywhere on earth (Fig. 2). In nations with limited conservation resources, this technique may prove particularly valuable.

Methods

Remote surveys and ground truthing

Google Earth (version 5.2.1.1588) was used to remotely explore the landscape-scale features of the shallow (< 5m depth) lagoon benthos of Heron Island, Queensland, Australia. Images were visually scanned for evidence of grazing halos surrounding isolated patch reefs. Once halos were identified, patch reef coordinates were entered into hand-held GPS units, which were subsequently used to navigate by foot and/or boat to individual patch reefs within halos identified in the image survey. Once located, ground truthing consisted of determining canopy height of algae surrounding the apparent halos. For 3 replicate transects per halo for three halos, canopy height was measured as the algal canopy height every 3m radiating from reef edges outwards to 30m. Height was measured at its maximum point at each distance within 1m on either side of transects.

Grazing assay

With the exception of the species used, our assay followed the protocol described in Hay 10. Clumps of Hincksia sp., the thin, filamentous alga whose beds provide the basis for the observed grazing halos, were clipped to 5.5cm lengths then attached to clips on benthic assay units. Assay units were placed every 3m in straight transects radiating outwards from the reef's edge to 12m. Three transects with two replicate clumps per unit were used. After being left in-situ for 72h, units were retrieved and clumps re-measured to the nearest 0.5cm. This assay measured the percent change in algal clump lengths over the three-day period. Assuming that all clumps would have experienced the same growth rate over this period, this provides a metric of relative grazing intensity at varying distances from the reef.

Author Contributions

EM and JM designed and executed the field surveys. EM wrote the main manuscript text and JM prepared figure 1D. All authors contributed intellectually and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Adam and Damian Thomson for initial idea discussion, Mark Hixon, Robert Warner, Dominic Johnson and Lesley Hughes for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, Guillermo Diaz for taxonomic assistance, and Peter Ralph for input in the field. Funding was provided by the US National Science Foundation and the Australian Research Council.

References

- Pringle H. Google Earth shows clandestine worlds. Science 329, 1008–1009 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill L. M., Heithaus M. R. & Walters C. J. Behaviorally mediated indirect interactions in marine communities and their conservation implications. Ecology 84, 1151–1157 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz O. J., Krivan V. & Ovadia O. Trophic cascades: the primacy of trait-mediated indirect interactions. Ecology Letters 7, 153–163, 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2003.00560.x (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ripple W. J. & Beschta R. L. Wolves and the ecology of fear: Can predation risk structure ecosystems? Bioscience 54, 755–766 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Randall J. E. Grazing effect on sea grasses by herbivorous reef fishes in the West-Indies. Ecology 46, 255–260 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J. C., Brown R. A., & Salesky N. Grazing by echinoid Diadema antillarum philippi - Formation of halos around West-Indian patch reefs. Science 182, 715–717 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madin E. M. P., Gaines S. D., Madin J. S. & Warner R. R. Fishing indirectly structures macroalgal assemblages by altering herbivore behavior. American Naturalist 176, 785–801 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madin E. M. P., Gaines S. D. & Warner R. R. Field evidence for pervasive indirect effects of fishing on prey foraging behavior. Ecology 91, 3563–3571 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creel S., Winnie J., Maxwell B., Hamlin K. & Creel M. Elk alter habitat selection as an antipredator response to wolves. Ecology 86, 3387–3397 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Hay M. E. Patterns of fish and urchin grazing on Caribbean coral reefs: are previous results typical? Ecology 65, 446–454 (1984). [Google Scholar]